Sonographic Anatomy and Normal Measurements of the Human Kidneys: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods of Literature Review

3. Normal Gross Anatomy

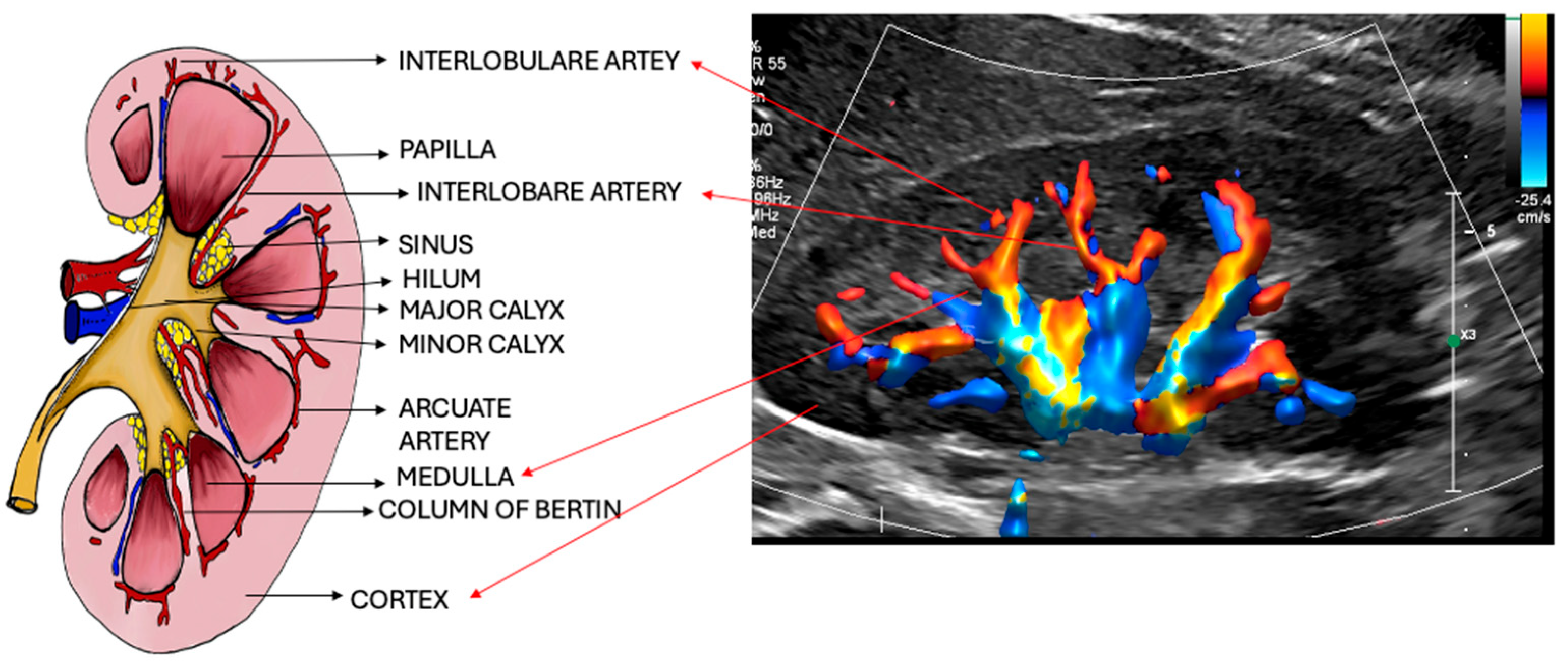

4. Intrarenal Anatomy

4.1. Renal Vascular Anatomy

4.1.1. Renal Artery

4.1.2. Renal Vein

5. Ultrasound Evaluation of Renal Parenchyma and Vasculature

5.1. B-Mode Ultrasound (Grayscale Imaging)

Imaging Techniques and Protocol

6. Shape and Appearance

7. Size

7.1. Kidney Volume

7.2. Too Large or Too Small?

8. Echogenicity

8.1. Cortical Thickness

8.2. Parenchymal Thickness

8.3. Cortico Medullary Ratio

8.4. Congenital Variations and Anomalies

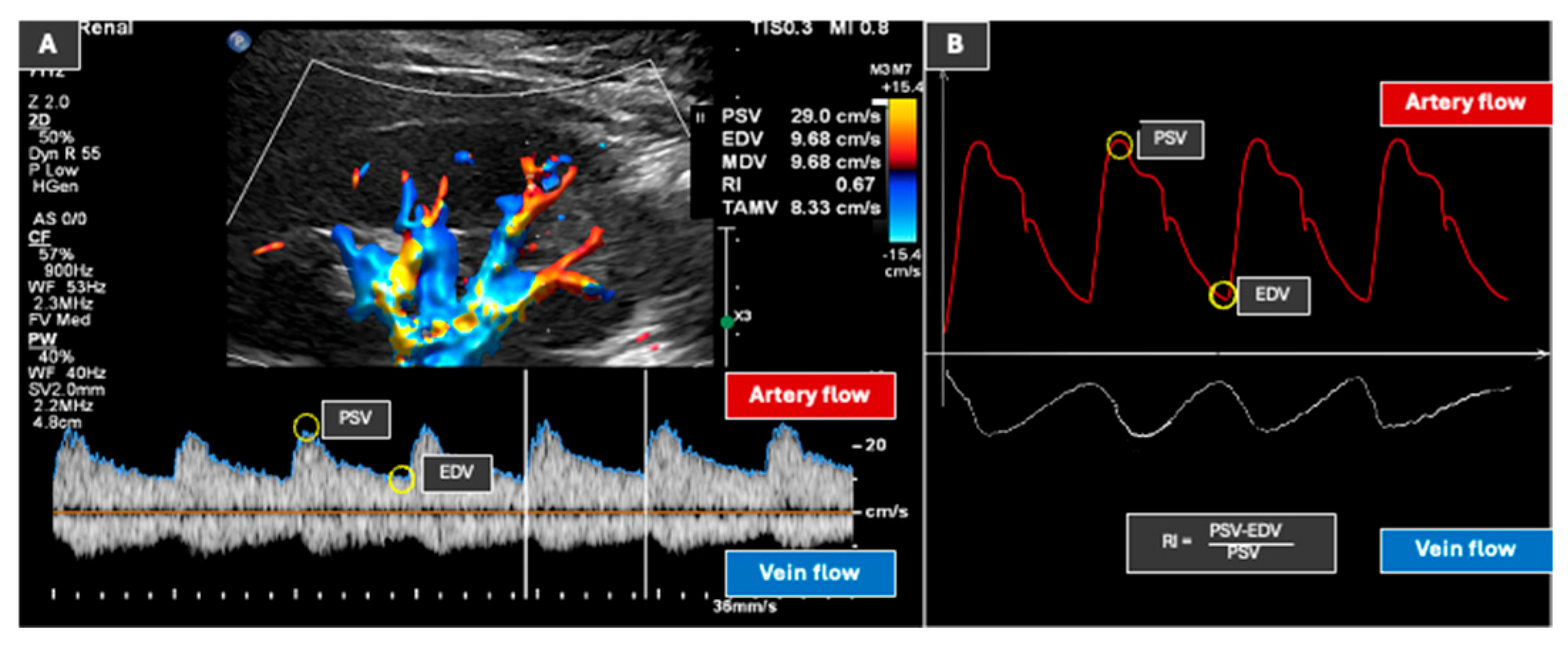

9. Doppler Ultrasound (Vasculature Assessment)

9.1. Masses

9.2. Kidney Stones

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niyyar, V.D.; O’Neill, W.C. Point-of-care ultrasound in the practice of nephrology. Kidney Int. 2018, 93, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosmanova, E.O.; Wu, S.; O’Neill, W.C. Application of ultrasound in nephrology practice. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009, 16, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, E.; Campi, R.; Amparore, D.; Bertolo, R.; Carbonara, U.; Erdem, S.; Ingels, A.; Kara, Ö.; Marandino, L.; Marchioni, M.; et al. Expanding the Role of Ultrasound for the Characterization of Renal Masses. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cè, M.; Felisaz, P.F.; Alì, M.; Re Sartò, G.V.; Cellina, M. Ultrasound elastography in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Ultrason. 2023, 50, 381–415. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, W. Atlas of Renal Ultrasound; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.J.; Changchien, C.S.; Kuo, C.H. Causes of increasing width of right anterior extrarenal space seen in ultrasonographic examinations. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1995, 23, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitterberger, M.; Pinggera, G.M.; Feuchtner, G.; Neururer, R.; Bartsch, G.; Gradl, J.; Pallwein, L.; Strasser, H.; Frauscher, F. Sonographic measurement of renal pelvis wall thickness as diagnostic criterion for acute pyelonephritis in adults. Ultraschall Med. 2007, 28, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E.G.; Bernhard, D.H.; Gundolf, K.; Wolfgang, W. Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koratala, A.; Bhattacharya, D.; Kazory, A. Point of care renal ultrasonography for the busy nephrologist: A pictorial review. World J. Nephrol. 2019, 8, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.L.; Nielsen, M.B.; Ewertsen, C. Ultrasonography of the Kidney: A Pictorial Review. Diagnostics 2015, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Katib, S.; Shetty, M.; Jafri, S.M.; Jafri, S.Z. Radiologic Assessment of Native Renal Vasculature: A Multimodality Review. Radiographics 2017, 37, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkvatan, A.; Ozdemir, M.; Cumhur, T.; Olçer, T. Multidetector CT angiography of renal vasculature: Normal anatomy and variants. Eur. Radiol. 2009, 19, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulas, E.; Wysiadecki, G.; Szymański, J.; Majos, A.; Stefańczyk, L.; Topol, M.; Polguj, M. Morphological and clinical aspects of the occurrence of accessory (multiple) renal arteries. Arch. Med. Sci. 2018, 14, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramulu, M.V.; Prasanna, L.C. Accessory renal arteries: Anatomical details with surgical perceptions. J. Anat. Soc. India 2016, 65, S55–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, R.; Ronald, A. Compendium of Human Anatomic Variation: Text, Atlas, and World Literature; Urban & Schwarzenberg: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, F.T. The aberrant renal artery. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1957, 50, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, R.; Prusak, B.F.; Mozes, M.F. Anatomic abnormalities of cadaver kidneys procured for purposes of transplantation. Am. Surg. 1986, 52, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.B.; Cawich, S.O.; Shah, S.D.; Aiken, W.; McGregor, R.G.; Brown, H.; Gardner, M.T. Accessory renal arteries in a Caribbean population: A computed tomography based study. Springerplus 2013, 2, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, U.; Oğuzkurt, L.; Tercan, F.; Kizilkiliç, O.; Koç, Z.; Koca, N. Renal artery origins and variations: Angiographic evaluation of 855 consecutive patients. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2006, 12, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W.Y.; Sung, D.J.; Park, B.J.; Kim, M.J.; Han, N.Y.; Cho, S.B.; Kang, C.H.; Kang, S.H. Perihilar branching patterns of renal artery and extrarenal length of arterial branches and tumour-feeding arteries on multidetector CT angiography. Br. J. Radiol. 2013, 86, 20120387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunz, L.M.B.R. Doppler Renal Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, S.W.; Sajjad, H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Renal Artery. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hostiuc, S.; Rusu, M.C.; Negoi, I.; Dorobanțu, B.; Grigoriu, M. Anatomical variants of renal veins: A meta-analysis of prevalence. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sośnik, H.; Sośnik, K. Renal vascularization anomalies in the Polish population. Pol. Przegl Chir. 2017, 89, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D. Ultrasonic Scanning of the Kidneys. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1981, 11, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hekmatnia, A.; Yaraghi, M. Sonographic Measurement of Absolute and Relative Renal Length in Healthy Isfahani Adults. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2004, 2, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sienz, M.; Ignee, A.; Dietrich, C.F. Sonography today: Reference values in abdominal ultrasound: Aorta, inferior vena cava, kidneys. Z. Gastroenterol. 2012, 50, 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Harmse, W. Normal variance in renal size in relation to body habitus. S. Afr. J. Radiol. 2011, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamian, S.A.; Nielsen, M.B.; Pedersen, J.F.; Ytte, L. Kidney dimensions at sonography: Correlation with age, sex, and habitus in 665 adult volunteers. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1993, 160, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Miletić, D.; Fuckar, Z.; Sustić, A.; Mozetic, V.; Stimac, D.; Zauhar, G. Sonographic measurement of absolute and relative renal length in adults. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1998, 26, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrycki, Ł.; Sarnecki, J.; Lichosik, M.; Sopińska, M.; Placzyńska, M.; Stańczyk, M.; Mirecka, J.; Wasilewska, A.; Michalski, M.; Lewandowska, W.; et al. Kidney length normative values in children aged 0–19 years—A multicenter study. Pediatr. Nephrol. Berl. Ger. 2022, 37, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, M.; Abukonna, A. Sonographic measurement of renal size in normal high altitude populations. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2017, 10, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, N.P.; Abbas, F.; Biyabani, S.R.; Afzal, M.; Javed, Q.; Rizvi, I.; Talati, J. Ultrasonographic renal size in individuals without known renal disease. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2000, 50, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.L.; Lafayette, R.A. Renal physiology of pregnancy. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013, 20, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, R.; Cardinale, L.; Lovaria, A.; Di Palo, F.Q. Variability of renal echo-Doppler measurements in healthy adults. J. Nephrol. 2000, 13, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Khosroshahi, H.T.; Tarzamni, M.; Oskuii, R.A. Doppler ultrasonography before and 6 to 12 months after kidney transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2005, 37, 2976–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlouli, A.; Tarzamni, M.K.; Zomorodi, A.; Abdollahifard, S.; Hashemi, B.; Nezami, N. Remnant kidney function and size in living unrelated kidney donors after nephrectomy. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2010, 21, 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, Z.; Mirza, W.; Sayani, R.; Sheikh, A.; Yazdani, I.; Hussain, S. Sonographic Measurement of Renal Dimensions in Adults and its Correlates. Int. J. Collab. Res. Intern. Med. Public Health 2012, 4, 1626–1641. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.; Yasmeen, S.; Adel, H.; Adil, S.O.; Huda, F.; Khan, S. Sonographic Evaluation of Normal Liver, Spleen, and Renal Parameters in Adult Population: A Multicenter Study. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2018, 28, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryaki, Ş.; Aksu, Y. Ultrasonographic Evaluation of Normal Liver, Spleen, and Kidney Dimensions in a Healthy Turkish Community of Over 18 Years Old. Curr. Med. Imaging 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cheok, S.P.; Kuan, B.B. Renal size in healthy Malaysian adults by ultrasonography. Med. J. Malays. 1989, 44, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, E.N.; West, W.M.; Sargeant, L.A.; Lindo, J.F.; Iheonunekwu, N.C. A sonographic study of kidney dimensions in a sample of healthy Jamaicans. West. Indian Med. J. 2000, 49, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Muthusami, P.; Ananthakrishnan, R.; Santosh, P. Need for a nomogram of renal sizes in the Indian population- findings from a single centre sonographic study. Indian J. Med. Res. 2014, 139, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Mejia, A. Kidney measurements by sonography on normal Filipino adults influence of age, sex, and habitus. Philipp. J. Intern. Med. 2001, 39, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Okoye, I.J.; Agwu, K.K.; Idigo, F.U. Normal sonographic renal length in adult southeast Nigerians. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2005, 34, 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Oyuela-Carrasco, J.; Rodríguez-Castellanos, F.; Kimura, E.; Delgado-Hernández, R.; Herrera-Félix, J.P. Renal length measured by ultrasound in adult mexican population. Nefrologia 2009, 29, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- El-Reshaid, W.; Abdul-Fattah, H. Sonographic assessment of renal size in healthy adults. Med. Princ. Pract. 2014, 23, 432–436. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.A.; Hsieh, H.Y.; Lee, C.T.; Liao, S.C.; Chu, C.H.; Wu, C.H. Reference ranges for ultrasonographic renal dimensions as functions of age and body indices: A retrospective observational study in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, A.S.; Majrashi, N.A.; Elbashir, M.; Ali, S.; Shubayr, N.; Refaee, T.; Ageeli, W.; Madkhali, Y.; Abdelrazig, A.; Althobity, A.A.; et al. Normal sonographic measurements for kidney dimensions in Saudi adult population: A cross-sectional prospective study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, J.; Olree, M.; Kaatee, R.; de Lange, E.E.; Moons, K.G.M.; Beutler, J.J.; Beek, F.J.A. Renal Volume Measurements: Accuracy and Repeatability of US Compared with That of MR Imaging. Radiology 1999, 211, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Akbari, P.; Pourafkari, M.; Iliuta, I.-A.; Guiard, E.; Quist, C.F.; Song, X.; Hillier, D.; Khalili, K.; Pei, Y. Prognostic Performance of Kidney Volume Measurement for Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Comparative Study of Ellipsoid vs. Manual Segmentation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Fowler, K.J.; Hamilton, G.; Cui, J.Y.; Sy, E.Z.; Balanay, M.; Hooker, J.C.; Szeverenyi, N.; Sirlin, C.B. Liver fat imaging-a clinical overview of ultrasound, CT, and MR imaging. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, J.; Morgan, S.; Eastwood, J.; Smith, S.; Webb, D.; Dilly, S.; Chow, J.; Pottier, A.; Joseph, A. Ultrasound findings in renal parenchymal disease: Comparison with histological appearances. Clin. Radiol. 1994, 49, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, A.A.; Fernandez, H.E. Ultrasonography in Acute Kidney Injury. POCUS J. 2022, 7, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, H.L. Quantitative derivates of renal radiologic studies. An overview. Investig. Radiol. 1972, 7, 240–279. [Google Scholar]

- Padigala, K.K.; Hartle, J.E.; Kirchner, H.L.; Schultz, M.F. Renal cortical thickness as a predictor of renal function and blood pressure status post renal artery stenting. Angiology 2009, 60, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikuta, A.; Ohya, M.; Kubo, S.; Osakada, K.; Takamatsu, M.; Takahashi, K.; Maruo, T.; Katoh, H.; Matsuo, T.; Nakano, J.; et al. Renal cortex thickness and changes in renal function after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention 2022, 17, e1407–e1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwafor, N.N.; Adeyekun, A.A.; Adenike, O.A. Sonographic evaluation of renal parameters in individuals with essential hypertension and correlation with normotensives. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourtsoyiannis, N.; Prassopoulos, P.; Cavouras, D.; Pantelidis, N. The thickness of the renal parenchyma decreases with age: A CT study of 360 patients. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 155, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.B. A structural approach to the assessment of fracture risk in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2007, 22, 1815–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkala, A.; Kallio, T.; Huhtala, H.; Apuli, P.; Paakkala, T.; Pasternack, A.; Mustonen, J. Renal ultrasound findings and their clinical associations in nephropathia epidemica. Analysis of quantitative parameters. Acta Radiol. 2002, 43, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A.; Porta, F.; Gianoglio, B.; Gaido, M.; Nicolosi, M.G.; De Terlizzi, F.; de Sanctis, C.; Coppo, R. Bone alterations in children and young adults with renal transplant assessed by phalangeal quantitative ultrasound. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2007, 50, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, D.S.; Hoisala, R.; Somiah, S.; Sheeba, S.D.; Yeung, M. Quantitation of change in the medullary compartment in renal allograft by ultrasound. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1997, 25, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, M. Angiographic measurement of renal compartments. Corticomedullary ratio in normal, diseased states and sickle cell anemia. Radiology 1974, 113, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, J.H.; McClellan, D.S. Crossed renal ectopia. Am. J. Surg. 1957, 93, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tublin, M.E.; Bude, R.O.; Platt, J.F. Review. The resistive index in renal Doppler sonography: Where do we stand? AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003, 180, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hélénon, O.; el Rody, F.; Correas, J.M.; Melki, P.; Chauveau, D.; Chrétien, Y.; Moreau, J.F. Color Doppler US of renovascular disease in native kidneys. Radiographics 1995, 15, 833–854; discussion 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.D.; Rysavy, J.A.; Frick, M.P. Intrarenal Doppler: Characteristics of aging kidneys. J. Ultrasound Med. 1992, 11, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, D.; Terlizzese, P.; Iacoviello, M. Role of imaging in the evaluation of renal dysfunction in heart failure patients. World J. Nephrol. 2017, 6, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, M.; Schnell, D.; Zeni, F. Doppler-Based Renal Resistive Index: A Comprehensive Review. In Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keogan, M.T.; Kliewer, M.A.; Hertzberg, B.S.; DeLong, D.M.; Tupler, R.H.; Carroll, B.A. Renal resistive indexes: Variability in Doppler US measurement in a healthy population. Radiology 1996, 199, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyridopoulos, T.N.; Kaziani, K.; Balanika, A.P.; Kalokairinou-Motogna, M.; Bizimi, V.; Paianidi, I.; Baltas, C.S. Ultrasound as a first line screening tool for the detection of renal artery stenosis: A comprehensive review. Med. Ultrason. 2010, 12, 228–232. [Google Scholar]

- Bosniak, M.A. Diagnosis and management of patients with complicated cystic lesions of the kidney. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1997, 169, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S.G.; Pedrosa, I.; Ellis, J.H.; Hindman, N.M.; Schieda, N.; Smith, A.D.; Remer, E.M.; Shinagare, A.B.; Curci, N.E.; Raman, S.S.; et al. Bosniak Classification of Cystic Renal Masses, Version 2019: An Update Proposal and Needs Assessment. Radiology 2019, 292, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantisani, V.; Bertolotto, M.; Clevert, D.-A.; Correas, J.-M.; Drudi, F.M.; Fischer, T.; Gilja, O.H.; Granata, A.; Graumann, O.; Harvey, C.J.; et al. EFSUMB 2020 Proposal for a Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound-Adapted Bosniak Cyst Categorization—Position Statement. Ultraschall Med. 2021, 42, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, C.F. Proposal for a Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound-Adapted Bosniak Cyst Categorization—Position Statement. Ultraschall Med. 2022, 43, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgan, C.M.; Sanyal, R.; Lockhart, M.E. Ultrasound of Renal Masses. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 57, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolau, C.; Antunes, N.; Paño, B.; Sebastia, C. Imaging Characterization of Renal Masses. Medicina 2021, 57, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.M.; Moin, P.; Dunn, M.D.; Boswell, W.D.; Duddalwar, V.A. What the radiologist needs to know about urolithiasis: Part 1—Pathogenesis, types, assessment, and variant anatomy. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012, 198, W540–W547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbane, W.; Bailey, M.R.; Sorensen, M.D. An overview of kidney stone imaging techniques. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2016, 13, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.D.; Hui, J.; Goldfarb, D.S. Asymptomatic nephrolithiasis detected by ultrasound. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.A.; Locken, J.A.; Duchesne, J.H.; Williamson, M.R. US for detecting renal calculi with nonenhanced CT as a reference standard. Radiology 2002, 222, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Urolithiasis; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.; Dighe, M.; Moller, K.; Chammas, M.C.; Dong, Y.; Cui, X.C.; Dietrich, C.F. Ultrasound measurements and normal findings in the thyroid gland. Med. Ultrason 2024, 27, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, K.; Saborio, M.; Gottschall, H.; Blaivas, M.; Borges, A.C.; Morf, S.; Moller, B.; Dietrich, C.F. The Perception of the Diaphragm with Ultrasound: Always There Yet Overlooked? Life 2025, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.; Jenssen, C.; Braden, B.; Hocke, M.; Hollerbach, S.; Ignee, A.; Faiss, S.; Iglesias-Garcia, J.; Sun, S.; Dong, Y.; et al. Pancreatic changes with lifestyle and age: What is normal and what is concerning? Endosc. Ultrasound 2023, 12, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.; Fischer, P.; Gilja, O.H.; Gottschall, H.; Jenssen, C.; Hollerweger, A.; Lucius, C.; Meier, J.; Rogler, G.; Misselwitz, B. Gastrointestinal Ultrasound: Measurements and Normal Findings—What Do You Need to Know? Dig. Dis. 2025, 43, 300–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, J.; Lucius, C.; Möller, K.; Jenssen, C.; Zervides, C.; Gschmack, A.M.; Dong, Y.; Srivastava, D.; Dietrich, C.F. Pancreatic ultrasound: An update of measurements, reference values, and variations of the pancreas. Ultrasound Int. Open 2024, 10, a23899085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucius, C.; Flückiger, A.; Meier, J.; Möller, K.; Jenssen, C.; Braden, B.; Kallenbach, M.; Misselwitz, B.; Nolsøe, C.; Sienz, M.; et al. Ultrasound of Bile Ducts-An Update on Measurements, Reference Values, and Their Influencing Factors. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 919. [Google Scholar]

- Lucius, C.; Braden, B.; Jenssen, C.; Möller, K.; Sienz, M.; Zervides, C.; Essig, M.W.; Dietrich, C.F. Ultrasound of the Gallbladder—An Update on Measurements, Reference Values, Variants and Frequent Pathologies: A Scoping Review. Life 2025, 15, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschmack, A.M.; Karlas, T.; Lucius, C.; Barth, G.; Blaivas, M.; Daum, N.; Dong, Y.; Goudie, A.; Hoffmann, B.; Jenssen, C.; et al. Measurement and Normal Values, Pathologies, Interpretation of findings, and Interventional Ultrasound as part of student ultrasound education. Z. Gastroenterol. 2025, 63, 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Sienz, M.; Ignee, A.; Dietrich, C.F. Reference values in abdominal ultrasound—Liver and liver vessels. Z. Gastroenterol. 2010, 48, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Sienz, M.; Ignee, A.; Dietrich, C.F. Reference values in abdominal ultrasound—Biliopancreatic system and spleen. Z. Gastroenterol. 2011, 49, 845–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Position | Clinical Purpose |

|---|---|

| Supine | Opens up rib spaces to facilitate better visualization |

| Lateral decubitus | To reduce bowel gas interface |

| Oblique | In obese patients |

| Prone | Occasionally used for posterior access |

| Standing | In cases of clinically relevant suspicion of kidney descent when standing. |

| Patient Type | Transducer Type | Frequency Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Curved array transducer | 1–6 MHz | For deep imaging |

| Pediatric | Linear array transducer | Higher frequency (>9 MHz) | Better resolution for superficial kidneys |

| Parameter | How to Measure |

|---|---|

| Length/maximum pole distance | Maximum length distance from the kidney contour at the upper pole to the contour at the lower pole. If the parenchymal margin at the upper and lower poles is of different thickness, the kidney is displayed tangentially. |

| Parenchymal thickness | From the outer contour to the tip of a medullary pyramid at a right angle. |

| Cortical thickness | From the outer contour to the base of the medullary pyramid or border between the cortex and medullary pyramid. |

| Author; Year (Reference) | Country | Sex | Kidney Length (cm) | Cortical Thickness (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al., 1989 [41] | Malaysia (205) | M | R = 10.2 | - |

| L = 10.5 | ||||

| F | R = 11.2 | - | ||

| L = 11.5 | ||||

| Emmanian et al., 1992 [29] | Denmark (665) | M | R = 11.0 | - |

| L = 11.0 | ||||

| F | R = 11.2 | - | ||

| L = 11.5 | ||||

| Both | R = 10.9 | - | ||

| L = 11.2 | ||||

| Buchholz et al., 2000 [33] | Pakistan (194) | M | R = 10.6 ± 0.8 | R = 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| L = 10.6 ± 0.8 | L = 1.7 ± 0.2 | |||

| F | R = 10.3 ± 0.8 | R = 1.5 ± 0.2 | ||

| L = 10.3 ± 0.8 | L = 1.5 ± 0.2 | |||

| Barton EN et al., 2000 [42] | Jamaica (39) | Both | R = 9.7 ± 0.7 | - |

| L = 10 ± 0.7 | ||||

| Muthusami et al., 2001 [43] | India (140) | Both | R = 9.6 ± 0.97 | * 1.4–2.7 |

| L = 9.71 ± 0.89 | ||||

| Dominguez-Mija et al., 2001 [44] | Philippines (264) | M | R = 9.6 | R = 0.42 L = 0.43 |

| L = 9.8 | ||||

| F | R = 9.5 | R = 0.39 L = 0.39 | ||

| L = 9.3 | ||||

| Hekmatnia A et al., 2004 [26] | Iran (230 M,170 F) | M | R = 11.0 ± 0.918 | - |

| L = 11.8 ± 1.04 | ||||

| F | R = 10.7 ± 0.637 | - | ||

| L = 10.9 ± 0.78 | ||||

| Okoye IU et al., 2006 [45] | Nigeria (309) | Both | R = 10.33 ± 0.7 | - |

| L = 10.45 ± 0.63 | ||||

| Oyuela-Carrasco et al., 2009 [46] | Mexico (153) | M | R = 10.57 | N/A |

| L = 10.72 | ||||

| F | R = 10.29 | |||

| L = 10.46 | ||||

| El-Reshaid et al., 2014 [47] | Kuwait (252) | M | R = 10.8 ± 0.9 | R = 0.98 ± 0.2 |

| L = 10.9 ± 0.8 | L = 1.02 ± 0.2 | |||

| F | R = 10.5 ± 1.1 | R = 0.98 ± 0.8 | ||

| L = 11.2 ± 0.9 | L = 1.02 ± 0.6 | |||

| Su et al., 2019 [48] | China (3707) | M | R = 10.76 ± 0.66 | R = 1.51 ± 0.31 |

| L = 10.87 ± 0.69 | L = 1.39 ± 0.31 | |||

| F | R = 10.41 ± 0.67 | R = 1.52 ± 0.29 | ||

| L = 10.59 ± 0.68 | L = 1.45 ± 0.29 | |||

| Khan SA et al., 2018 [39] | Pakistan (2212) | M | R = 10.30 ± 0.87 | R=1.19 ± 0.12 |

| L = 10.38 ± 0.98 | ||||

| F | R = 10.18 ± 1.22 | L = 1.26 ± 0.14 | ||

| L = 10.23 ± 0.92 | ||||

| Tiryaki S et al., 2023 [40] | Turkey (1918) | M | R = 11.01 ± 0.72 | # R = 1.52 ± 0.16 |

| L = 11.38 ± 0.74 | L = 1.56 ± 0.16 | |||

| F | R = 10.45 ± 0.65 | R = 1.42 ± 0.14 | ||

| L = 10.75 ± 0.65 | L = 1.45 ± 0.13 | |||

| Ali S Aliyami et al., 2024 [49] | Saudi Arabia (55 M, 40 F) | M | R = 9.96 ± 1.21 | - |

| L = 10.4 ± 0.78 | ||||

| F | R = 9.53 ± 0.636 | - | ||

| L = 9.64 ± 1.14 |

| Parameter | Reference Values |

|---|---|

| Length/maximum pole distance | 10–12 cm |

| Parenchymal thickness | >15 mm |

| Cortical thickness | >5 mm |

| Too Large | Too Small |

|---|---|

| Double kidney | Unilateral: |

| Compensatory hypertrophy in single kidney | congenital dysplasia |

| Pregnancy | renal artery stenosis |

| Early-stage diabetic nephropathy | Bilateral: |

| Acute nephritis | Chronic glomerulonephritis |

| Acute renal failure | Chronic pyelonephritis |

| Transplant rejection | Advanced diabetic nephropathy |

| Right heart failure with venous congestion and retrograde flow | Advanced arteriolonephrosclerosis |

| Renal vein thrombosis | Shrinking kidneys in end-stage renal failure |

| Urinary retention | |

| Crush injury | |

| Amyloidosis |

| Intrarenal Structure | Ultrasound Appearance |

|---|---|

| Cortex | Isoechoic or hypoechoic compared to non steatotic liver/spleen |

| Medullary Pyramid | Hypoechoic |

| Sinus Fat | Brightly echogenic |

| Renal Column of Bertin | Similarly to cortex; Continuous with cortex |

| Arcuate Vessels | Hyperechoic dots at -medullary medullary border |

| Collecting System | Not visualized unless distended with urine |

| Renal Echogenicity | |

|---|---|

| Hyperechoic | Hypoechoic |

| Chronic kidney disease | Cortical necrosis |

| Acute interstitial nephritis | Hemorrhagic infarcts |

| Amyloidosis | Lymphoma |

| Congenital Changes in the Kidneys | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Changes | Description | Meaning |

| Changes in the Renal Surface | ||

| Fetal lobulation “Renculation” | Uniform contour retractions over the columnae renales. Regular in neonates and very young children, rare in adults. | Can be confused (in adults) with scars. |

| Physiological spleen hump left | Protrusion at the outer contour of the parenchyma in the middle third. Parenchymal architecture with medullary pyramids and columnae renales and vascular branching in the parenchyma is preserved. | Misinterpretation of is echogenic tumors and parenchymal swelling (hematoma, melting-in inflammation). |

| Retraction at the parenchyma of the right kidney close to the liver | Transducer position and sonic angle-related retraction in the renal hilus. | Misinterpretation as a wedge-shaped scar. |

| Parenchymal changes | ||

| Parenchyma cone (Bertin’s column) | Hypertrophied columnae renales, traversing vessels are preserved. Lateral to the parenchymal cones are the medullary pyramids. Parenchymal cones may be located centrally or asymmetrically. | Misinterpretation as echogenic tumors, especially if echogenicity is altered due to artifact. |

| Parenchymal bridges | The renal sinus is divided by one (or more) parenchymal bridges. | In itself, this is a typical finding. Part of a double kidney. |

| Kidney malformations | ||

| Congenital changes in number and position | ||

| Agenesia, Aplasia | Unapplied kidney. | Differential diagnosis to the condition after nephrectomy or to the dystopic kidney in other localization. |

| Hypoplasia | Small kidney with smooth contour and preserved architecture. Rule one-sided. | Differential diagnosis from renal artery stenosis with unilateral renal reduction, from unilateral shrunken kidney with altered, usually poorly demarcated kidney. Chronic kidney disease is usually associated with bilateral reduction in size. |

| Dystopia, Malposition (Ectopy) | The kidney is not in the usual position. Thoracic position in newborns, which impedes respiratory activity and must be quickly corrected surgically. Low kidney, low lumbar position, pelvic position. | If the kidney is not found, it is necessary to search in other positions. Common association with malrotation and fusion abnormalities. |

| Malrotation | The kidney is rotated in its axes. The kidney may be at a different angle and the hilus may be rotated. Association with other fusion anomalies and congenital kidney changes. | The kidney may not be recognizable and tumor-like images may be seen. |

| Fusion anomalies | ||

| Double kidney | Large kidneys with parenchymal bridge and contour retraction above the parenchymal bridge with division of the renal sinus, including the renal pelvis. One kidney remains, not a true division into two kidneys. | Usually no diagnostic difficulty. |

| Horseshoe kidney | Large kidneys on both sides, usually double kidneys, parenchymal bridges. Often deeper located. The caudal pole is displaced medially and the inferior poles of both kidneys fuse over the aorta. | Solid mass over the aorta may be misinterpreted as a colon tumor. |

| Pelvic kidney | Pelvic location of a kidney or fused kidney. | Can be misinterpreted as a solid tumor. Distinguished from congenital pelvic position must be atypical mobility: drop kidney or ren mobilis. |

| Sigmoid kidney | One half or part of the kidney is rotated around the axis and fused with the other part. Parenchyma is adjacent to sinus and vice versa. | Tumor-like images are formed, triggering unnecessary diagnostics. |

| Cake kidney | In a pie kidney, both kidneys are fused into one and lie in front of the os saccrum. There is only one ureter. In the pie kidney, there is megacalicosis with dilated calyces. | The kidney of the cake can be confused with a (cystic) solid tumor. |

| Urinary flow disorders | ||

| Ectopic ureteral orifice with obstruction | Ureteral dilatation | Urinary retention |

| Ectopic ureteral orifice with reflux syndrome | Visualization by retrograde radiological contrast or intravesical ultrasound contrast application with visualization of the contrast agent in the renal sinus. | Frequent urinary tract infections. |

| Crossing of the ureters | The ureters cross and open on the opposite side.

| Cannot be visualized on ultrasound without visualization of the course of the ureters. Combination with other renal malformations/fusional relicts. |

| Ureteral outlet stenosis | Congenital constriction at the transition from the pyelon to the ureter. This can also be caused by transverse vessels. | Ureteral outlet stenosis can lead to hydronephrosis and impaired kidney function if it goes undetected. |

| Calyx diverticulum | Diverticula of the renal calices, appear like cysts. | Cannot be distinguished from cysts on ultrasound without excretory urography. |

| Megacalix | The collecting tube and the papillae are missing. Flared calyxes without congestion of the calyx necks and the renal pelvis. | Differentiation from urinary retention and renal cysts. |

| Congenital cysts | ||

| Primary cysts (malformations) | ||

| Polycystic kidney degeneration | ||

| Adult familial cystic kidneys/adult form (autosomal dominant) | Enlarged kidneys with multiple cysts such that the original parenchyma and renal sinus cannot be delineated. Cysts may also occur in the liver and pancreas. | Terminal renal failure in adulthood. Familial clustering. |

| Juvenile cystic kidneys/from birth (autosomal recessive) | Cystic kidneys completely degenerated from birth, thousands of tiny cysts of a few millimeters. | Terminal renal failure in childhood |

| Renal Pathologies | Doppler Findings |

|---|---|

| Renal artery stenosis |

|

| Renal artery thrombosis |

|

| Renal artery aneurysm |

|

| Pseudoaneurysm |

|

| Post-biopsy arterio-venous fistula (AVF |

|

| Renal vein thrombosis or external compression |

|

| Renal Mass | Imaging Features | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant solid masses | RCC |

| |

| Urothelial carcinoma |

| ||

| Benign solid masses | Oncocytoma |

| |

| Angiomyolipoma (AML) | AML Classic |

| |

| AML |

| ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yadav, M.; Srivastava, S.; Dighe, M.; Möller, K.; Jenssen, C.; Dietrich, C.F. Sonographic Anatomy and Normal Measurements of the Human Kidneys: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243208

Yadav M, Srivastava S, Dighe M, Möller K, Jenssen C, Dietrich CF. Sonographic Anatomy and Normal Measurements of the Human Kidneys: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243208

Chicago/Turabian StyleYadav, Madhvi, Saubhagya Srivastava, Manjiri Dighe, Kathleen Möller, Christian Jenssen, and Christoph Frank Dietrich. 2025. "Sonographic Anatomy and Normal Measurements of the Human Kidneys: A Comprehensive Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243208

APA StyleYadav, M., Srivastava, S., Dighe, M., Möller, K., Jenssen, C., & Dietrich, C. F. (2025). Sonographic Anatomy and Normal Measurements of the Human Kidneys: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243208