The Value of Histopathological and Clinical Characteristics for the Assessment of the Prognosis and the Efficacy of Dynamic Anterior Stabilization Surgical Treatment for Shoulder Instability

Abstract

1. Introduction

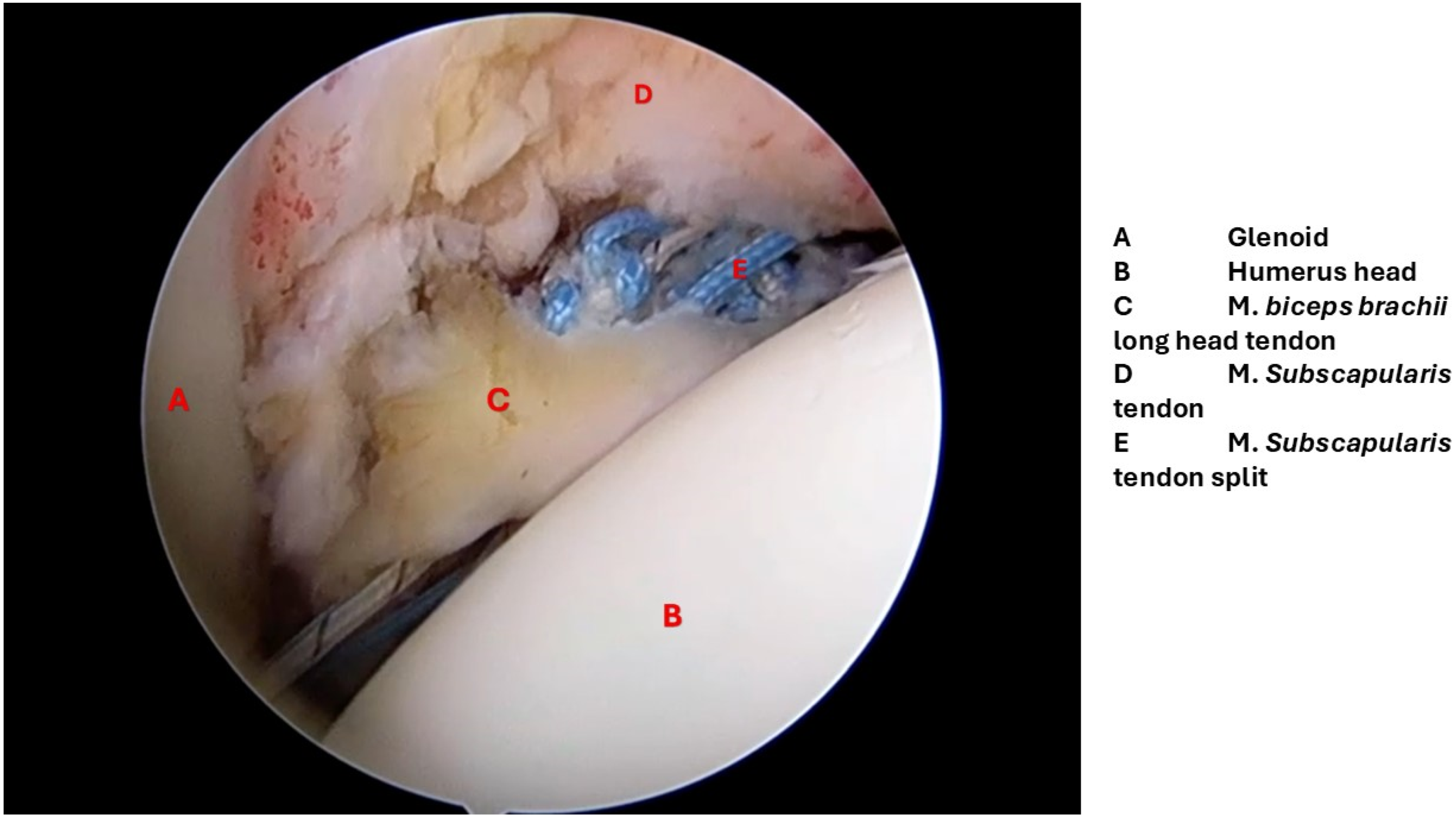

2. Materials and Methods

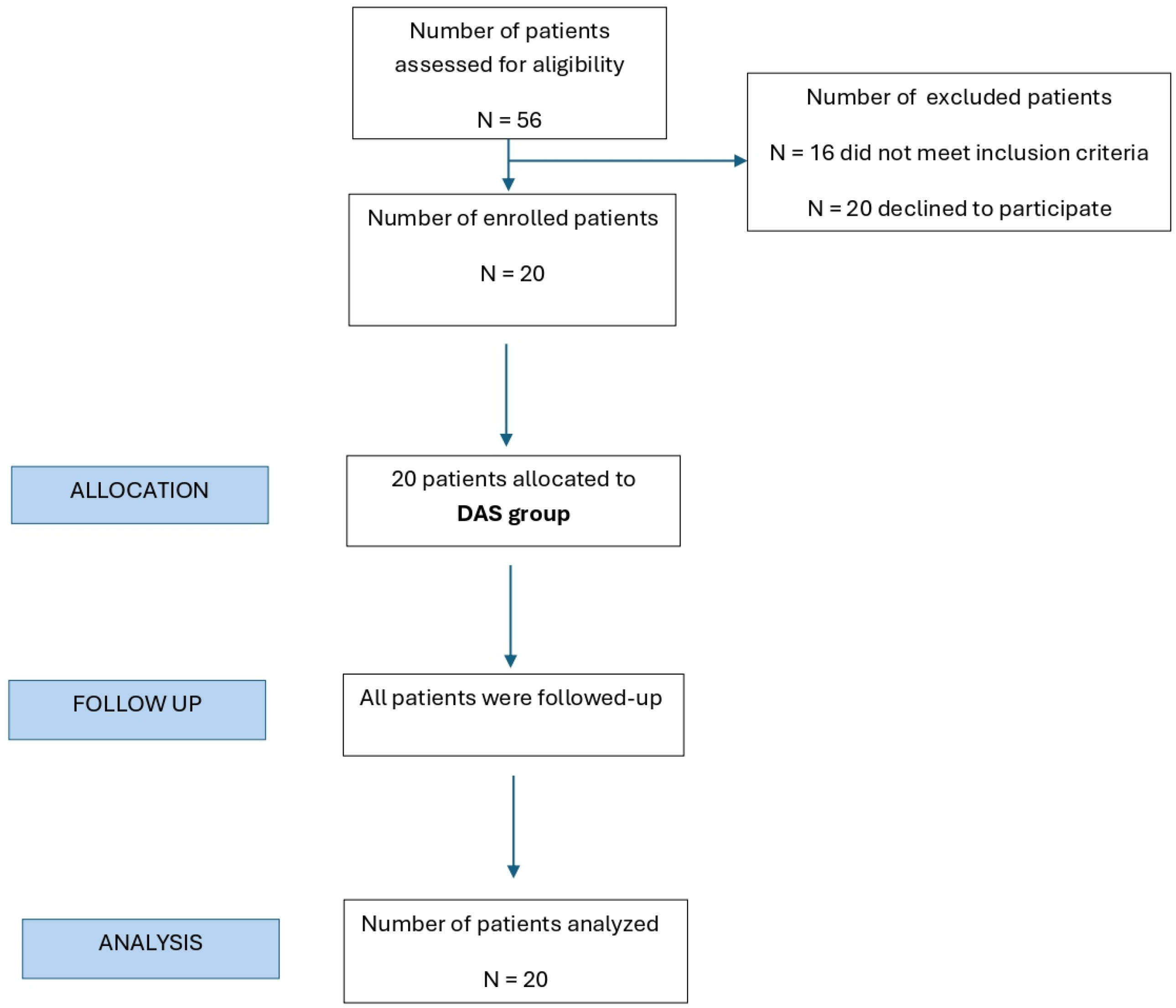

2.1. Study Design and Population

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Age under 50 years.

- History of anterior shoulder luxation or subluxation.

- Ongoing anterior shoulder instability.

- MRI-confirmed anterior labral lesion and Hill–Sachs lesion.

- CT-confirmed glenoid bone loss involving 10–20% of the total articulating surface.

- Age over 50 years.

- Presence of other structural damage within the shoulder joint.

- Multidirectional shoulder instability.

- Previous surgical intervention on the affected shoulder.

- Acute infection.

- Blood coagulation disorders.

- Systemic illnesses such as type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or autoimmune diseases.

- Any missing clinical, histopathological, and imaging data.

2.2. Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

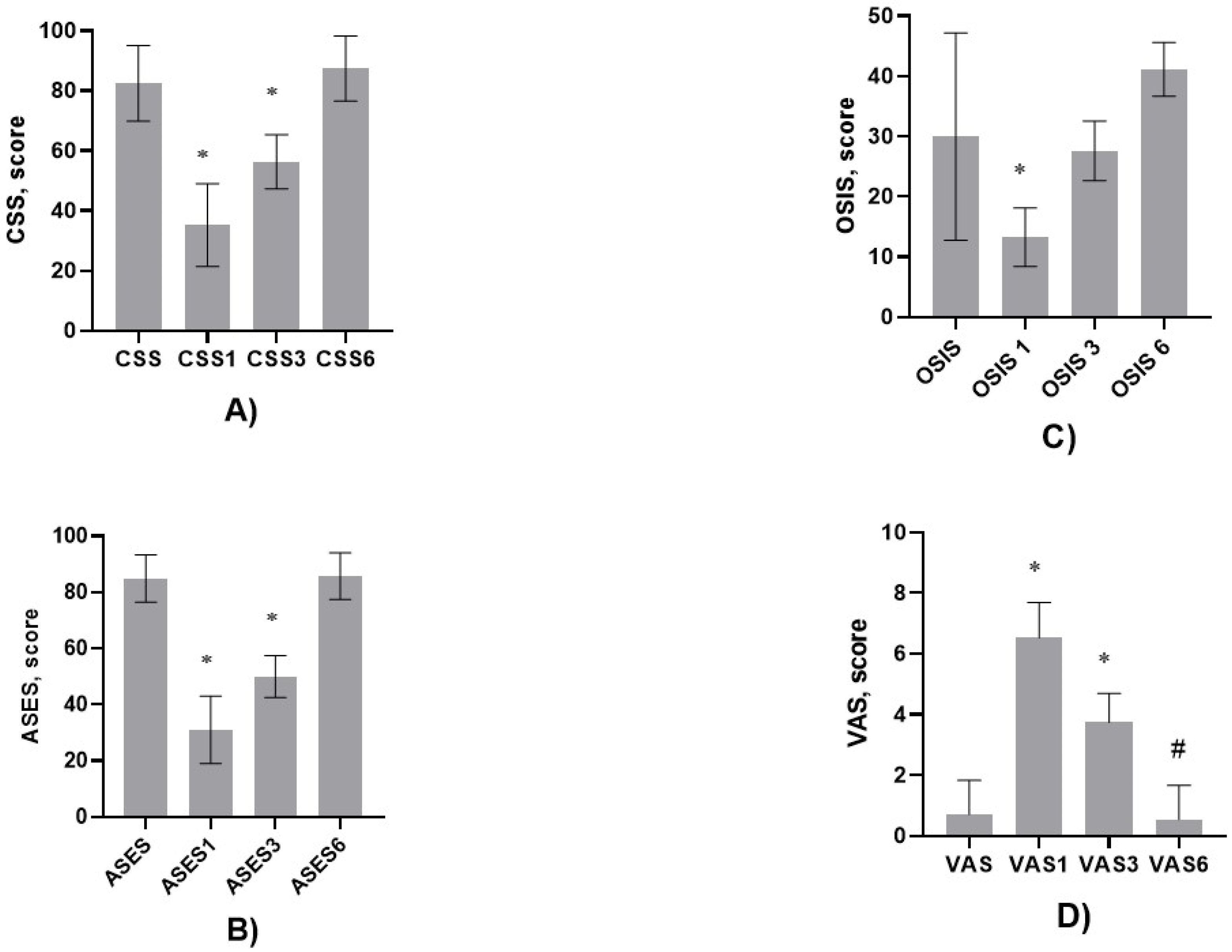

2.3. Clinical Evaluation, Follow-Up Schedule, and Rehabilitation

- Constant Shoulder Score (CSS).

- American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Score.

- Oxford Shoulder Instability Score (OSIS).

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS).

Histopathological Examination

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varacallo, M.A.; Musto, M.A.; Mair, S.D. Anterior Shoulder Instability. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538234/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Gasbarro, G.; Bondow, B.; Debski, R. Clinical anatomy and stabilizers of the gleno-humeral joint. Ann. Joint 2017, 2, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, D.; Aydin, N.; Yamamoto, N.; Simone, J.P.; Robles, P.P.; Tytherleigh-Strong, G.; Gobbato, B.; Kholinne, E.; Jeon, I.-H. Current concepts in anterior glenohumeral instability: Diagnosis and treatment. SICOT-J 2021, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollick, N.C.; Ono, Y.; Kurji, H.M.; Nelson, A.A.; Boorman, R.S.; Thornton, G.M.; Lo, I.K. Long-term outcomes of the Bankart and Latarjet repairs: A systematic review. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2017, 8, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tupe, R.N.; Tiwari, V. Anteroinferior Glenoid Labrum Lesion (Bankart Lesion). In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587359/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Provencher, M.T.; Frank, R.M.; Leclere, L.E.; Metzger, P.D.; Ryu, J.J.; Bernhardson, A.; Romeo, A.A. The Hill-Sachs lesion: Diagnosis, classification, and management. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2012, 20, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.; Shukla, T.; Vala, P. Managing severe bipolar bone loss in athletes: A comprehensive approach with open Latarjet and arthroscopic remplissage. J. Orthop. 2024, 51, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenin, O.; Toussaint, B. Labral Repair Augmentation by Labroplasty and Simultaneous Trans-Subscapular Transposition of the Long Head of the Biceps. Arthrosc. Tech. 2019, 8, e507–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, P.; Lädermann, A. Dynamic Anterior Stabilization Using the Long Head of the Biceps for Anteroinferior Glenohumeral Instability. Arthrosc. Tech. 2017, 7, e39–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos Azevedo, C.I.; Ângelo, A.C. Dynamic Anterior Stabilization of the Shoulder: Onlay Biceps Transfer to the Anterior Glenoid Using the Double Double-Pulley Technique. Arthrosc. Tech. 2023, 12, e1097–e1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos Azevedo, C.; Ângelo, A.C. Onlay Dynamic Anterior Stabilization with Biceps Transfer for the Treatment of Anterior Glenohumeral Instability Produces Good Clinical Outcomes and Successful Healing at a Minimum 1 Year of Follow-Up. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2023, 5, e445–e457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, E.J.; Kutschke, M.J.; He, E.; Owens, B.D. Biomechanics and Pathoanatomy of Posterior Shoulder Instability. Clin. Sports. Med. 2024, 43, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, D.W.; Compston, J.E.; Drezner, M.K.; Glorieux, F.H.; Kanis, J.A.; Malluche, H.; Meunier, P.J.; Ott, S.M.; Recker, R.R.; Parfitt, A.M. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: A 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonazza, N.A.; Riboh, J.C. Management of Recurrent Anterior Shoulder Instability After Surgical Stabilization in Children and Adolescents. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2020, 13, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhart, S.S.; De Beer, J.F. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: Significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 2000, 16, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locher, J.; Wilken, F.; Beitzel, K.; Buchmann, S.; Longo, U.G.; Denaro, V.; Imhoff, A.B. Hill-Sachs off-track lesions as risk factor for recurrence of instability after arthroscopic Bankart repair. Arthroscopy 2016, 32, 1993–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorzelski, J.; Fritz, E.M.; Horan, M.P.; Katthagen, J.C.; Provencher, M.T.; Millett, P.J. Failure following arthroscopic Bankart repair for traumatic anteroinferior instability of the shoulder: Is a glenoid labral articular disruption (GLAD) lesion a risk factor for recurrent instability? J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2018, 27, e235–e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciero, R.A.; Parrino, A.; Bernhardson, A.S.; Diaz-Doran, V.; Obopilwe, E.; Cote, M.P.; Golijanin, P.; Mazzocca, A.D.; Provencher, M.T. The effect of a combined glenoid and Hill-Sachs defect on glenohumeral stability: A biomechanical cadaveric study using 3-dimensional modeling of 142 patients. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, J.W.; Ruzbarsky, J.J.; Midtgaard, K.; Peebles, L.; Bradley, J.P.; Provencher, M.T. Defining Critical Glenoid Bone Loss in Posterior Shoulder Capsulolabral Repair. Am. J. Sports. Med. 2021, 49, 2013–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliart, N.; Gagey, O.J. The arthroscopic view of the glenohumeral ligaments compared with anatomy: Fold or fact? J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2005, 14, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Shimokobe, H.; Miyamoto, A.; Furushima, K. Arthroscopic findings of the glenohumeral joint in symptomatic anterior instabilities: Comparison between overhead throwing disorders and traumatic shoulder dislocation. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2023, 32, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi, T.; Furushima, K.; Takahashi, T.; Miyamoto, A.; Urata, D.; Yoshino, K.; Sugawara, M. Anterior glenohumeral capsular ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft for internal impingement with anterior instability of the shoulder in baseball players: Preliminary surgical outcomes. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2022, 31, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, Y.; Funakoshi, T.; Hara, K.; Higuchi, K.; Miyamoto, A.; Nakamura, H.; Gotoh, M. Dynamic Anterior Glenohumeral Capsular Ligament Tensioning During Arthroscopic Shoulder Stabilization in Overhead-Throwing Athletes. Arthrosc. Tech. 2024, 13, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, H.; Jiang, Y.; Song, Q.; Cheng, X.; Cui, G. Clinical and Radiologic Outcomes of All-Arthroscopic Latarjet Procedure With Modified Suture Button Fixation: Excellent Bone Healing with a Low Complication Rate. Arthroscopy 2022, 38, 2157–2165.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateschrang, A.; Ahmad, S.S.; Stöckle, U.; Schroeter, S.; Schenk, W.; Ahrend, M.D. Recovery of ACL function after dynamic intraligamentary stabilization is resultant to restoration of ACL integrity and scar tissue formation. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2018, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl, J.; Otto, A.; Imhoff, F.B.; Murphy, M.; Dyrna, F.; Obopilwe, E.; Cote, M.; Lädermann, A.; Collin, P.; Beitzel, K.; et al. Dynamic Anterior Shoulder Stabilization with the Long Head of the Biceps Tendon: A Biomechanical Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokshan, S.L.; Gil, J.A.; DeFroda, S.F.; Badida, R.; Crisco, J.J.; Owens, B.D. Biomechanical Comparison of the Long Head of the Biceps Tendon Versus Conjoint Tendon Transfer in a Bone Loss Shoulder Instability Model. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2019, 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanaliato, J.P.; Kerzner, B.; Bach, B.R., Jr.; Garrigues, G.E. Long Head of the Biceps Tendon Pathology: From Etiology to Management. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2025, 33, e1191–e1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huri, G.; Popescu, I.A.; Rinaldi, V.G.; Marcheggiani Muccioli, G.M. The Evolution of Arthroscopic Shoulder Surgery: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.F.; Glass, E.A.; Swanson, D.P.; Patti, J.; Bowler, A.R.; Le, K.; Jawa, A.; Kirsch, J.M. Predictors of poor and excellent outcomes following reverse shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis with an intact rotator cuff. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2024, 3, S55–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitar, I.J.; Bustos, D.G.; Marangoni, L.D.; Robles, C.; Gentile, L.; Bertiche, P. Outcomes of Open Bankart Repair Plus Inferior Capsular Shift Compared with Latarjet Procedure in Contact Athletes with Recurrent Anterior Shoulder Instability. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2023, 11, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Patients’ age, years | 30.55 ± 7.65 |

| Male/female ratio | 17/3 |

| First dislocation surgery (months) | 35 (2–97) |

| Shoulder dislocation (time)/reduction in hospital | 4 (range 2–12) |

| Dislocations, median (range), n | 6 (2–9) |

| Surgery after last dislocation, months | 35 (2–97) |

| X-ray, glenoid defect, % | 13.90 ± 3.08 |

| Soft tissue, leukocyte score | 1 (0–2) |

| Soft tissue, lymphocyte score | 1 (0–2) |

| Tissue area, mm2 | 34 ± 6.24 |

| Bone area, mm2 | 22.6 ± 8.12 |

| Bone volume, % | 52.8 ± 17.4 |

| Peritrabecular fibrosis | 1 (1–2) |

| Osteonecrosis, % | 6.35 ± 7.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Finogejevs, A.; Jumtiņš, A.; Moritis, E.T.; Isajevs, S. The Value of Histopathological and Clinical Characteristics for the Assessment of the Prognosis and the Efficacy of Dynamic Anterior Stabilization Surgical Treatment for Shoulder Instability. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243203

Finogejevs A, Jumtiņš A, Moritis ET, Isajevs S. The Value of Histopathological and Clinical Characteristics for the Assessment of the Prognosis and the Efficacy of Dynamic Anterior Stabilization Surgical Treatment for Shoulder Instability. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243203

Chicago/Turabian StyleFinogejevs, Andrejs, Andris Jumtiņš, Eduards Toms Moritis, and Sergejs Isajevs. 2025. "The Value of Histopathological and Clinical Characteristics for the Assessment of the Prognosis and the Efficacy of Dynamic Anterior Stabilization Surgical Treatment for Shoulder Instability" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243203

APA StyleFinogejevs, A., Jumtiņš, A., Moritis, E. T., & Isajevs, S. (2025). The Value of Histopathological and Clinical Characteristics for the Assessment of the Prognosis and the Efficacy of Dynamic Anterior Stabilization Surgical Treatment for Shoulder Instability. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243203