The Blood Supply of the Stomach: Anatomical and Surgical Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Arterial System of the Stomach and Its Variations

2.1. Left Gastric Artery

2.2. Right Gastric Artery

2.3. Left and Right Gastroepiploic Arteries

2.4. Other Constant and Inconstant Arterial Branches

3. Venous System of the Stomach and Its Variations

3.1. Gastric Veins

3.2. Gastroepiploic Veins

3.3. Other Constant and Inconstant Venous Branches

4. Surgical Importance of Stomach Vascular Variations

4.1. Implications for Gastric Cancer Gastrectomy

- Lesser curvature and suprapancreatic corridor (stations 7, 8a, 9, 11p): the LGV most often courses posterior to the CHA or anterior to the LGA; recognizing this pattern helps avoid avulsion during high ligation of the LGA and station-7 dissection [30]. Classify the LGV preoperatively relative to the CHA/SA/pancreas. Intraoperative video-based classification in 217 laparoscopic radical gastrectomy cases found type I (LGV running between the CHA posteriorly and the CA-Figure 4) to be most common (56%), whereas type IV (between SA posteriorly and CA-Figure 5) carried the highest bleeding risk (42%) and was an independent predictor of LGV injury on multivariable analysis [32,45] (Figure 4 and Figure 5). 3D MDCT classifications also emphasize that the LGV may terminate variably into the PV, SV, or their confluence—information that guides safe exposure at the pancreatic head and coeliac axis [40]. When a replaced/accessory left hepatic artery arises from the LGA, D2 dissection must preserve arterial inflow while clearing nodal tissue—an approach illustrated in operative atlases focused on variation-aware D2 technique [6].

- Infrapyloric basin (station 6) and the gastrocolic venous trunk (of Henle): the RGEV exhibits several confluence types with the aSPDV and colic veins; anticipating whether a gastro-pancreatic or gastro-colic trunk is present reduces bleeding during infrapyloric node clearance and kocherisation [37]. A meta-analysis places the venous trunk of Henle (gastrocolic trunk) in ~87% of patients—most commonly as a gastro-pancreato-colic configuration—underscoring why meticulous venous identification matters before dividing the RGEV [41].

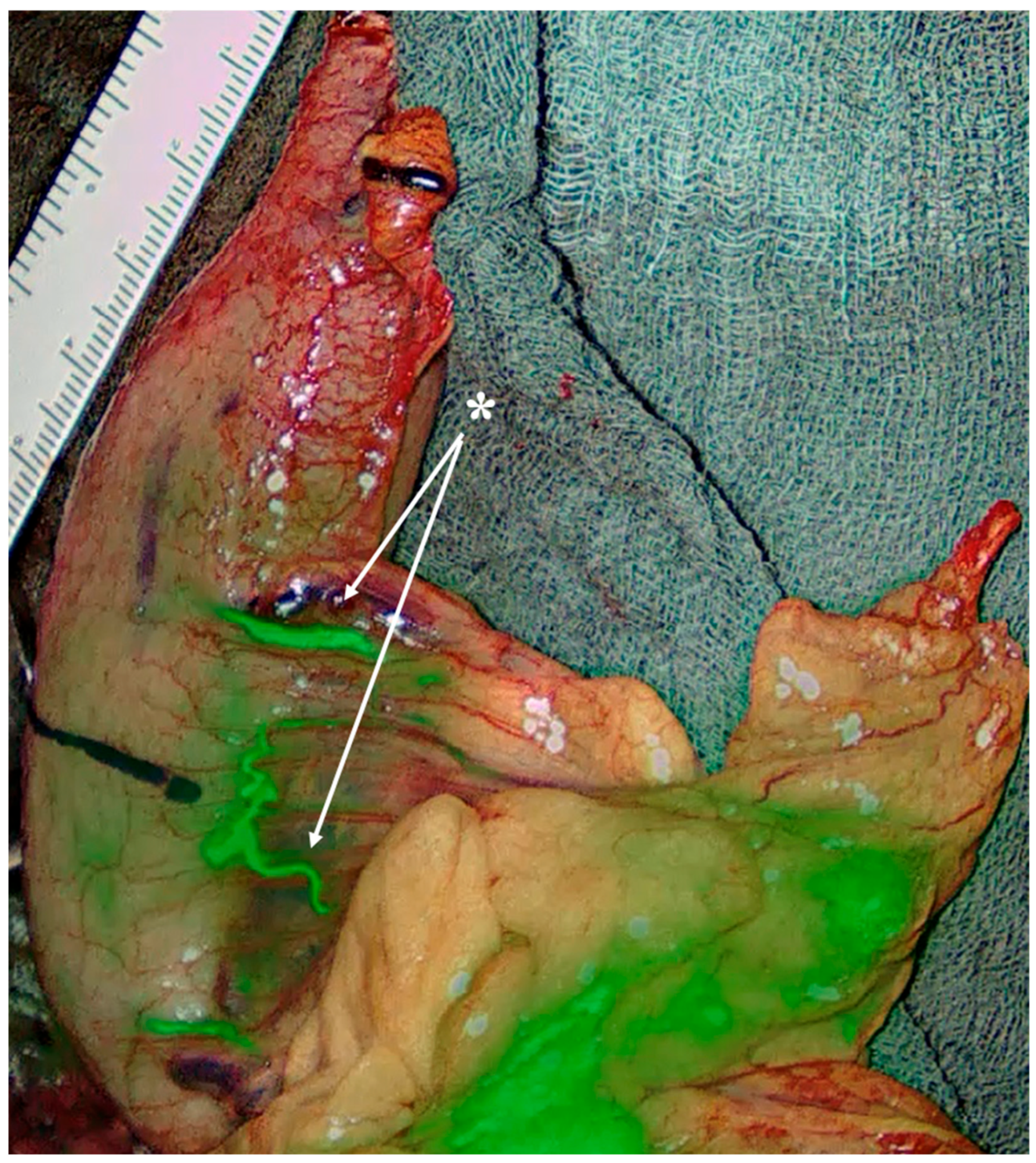

- Special consideration for PGA presence (approximately 57%): it represents a major inflow to the planned gastric remnant. Lymphatics course along the PGA, but D2 lymphadenectomy does not necessitate PGA division if nodal clearance can be performed while preserving arterial inflow. Preoperative MDCT can easily detect the PGA, while inadvertent ligation has been linked to stump ischemia/leak—use selective preservation and, if divided, confirm stump perfusion intraoperatively [27,28] (Figure 6).

4.2. Implications for Bariatric Surgery

4.3. Implications for Esophagectomies

4.4. Implications for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Embolization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Abdominal aorta |

| aSPDV | Anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein |

| CeT | Coeliac trunk |

| CHA | Common hepatic artery |

| D2 | Second-tier (extended) lymphadenectomy |

| GDA | Gastroduodenal artery |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| LGA | Left gastric artery |

| LGV | Left gastric vein |

| LGEA | Left gastroepiploic artery |

| LGEV | Left gastroepiploic vein |

| LSG | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy |

| MDCT | Multidetector computed tomography |

| PHA | Proper hepatic artery |

| PGA | Posterior gastric artery |

| PV | Portal vein |

| RGA | Right gastric artery |

| RGV | Right gastric vein |

| RGEA | Right gastroepiploic artery |

| RGEV | Right gastroepiploic vein |

| RYGB | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

| SA | Splenic artery |

| SMV | Superior mesenteric vein |

| SV | Splenic vein |

References

- Standring, S.; Anand, N.; Birch, R.; Collins, P.; Crossman, A.; Gleeson, M.; Jawaheer, G.; Smith, A.; Spratt, J.; Stringer, M.; et al. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aharinejad, S.; Lametschwandtner, A.; Franz, P.; Firbas, W. The Vascularization of the Digestive Tract Studied by Scanning Electron Microscopy with Special Emphasis on the Teeth, Esophagus, Stomach, Small and Large Intestine, Pancreas, and Liver. Scanning Microsc. 1991, 5, 811–849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Iwashita, A.; Kikuchi, Y.; Yao, T.; Matsui, T.; Tanabe, H.; Nagahama, T.; Sou, S. Novel Zoom Endoscopy Technique for Visualizing the Microvascular Architecture in Gastric Mucosa. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 3, S23–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, K.; Hann von Weyhern, C.; Slotta-Huspenina, J.; Burian, M.; Clevert, D.A.; Meining, A.; Prinz, C.; Pachmann, C.; Holzapfel, K.; Schmid, R.M.; et al. Microcirculation of Subepithelial Gastric Tumors Using Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2010, 45, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirocchi, R.; Randolph, J.; Davies, R.J.; Cheruiyot, I.; Gioia, S.; Henry, B.M.; Carlini, L.; Donini, A.; Anania, G. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Variants of the Branches of the Superior Mesenteric Artery: The Achilles Heel of Right Hemicolectomy with Complete Mesocolic Excision? Color. Dis. 2021, 23, 2834–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi, R.; D’Andrea, V.; Amato, B.; Renzi, C.; Henry, B.M.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Gioia, S.; Lancia, M.; Artico, M.; Randolph, J. Aberrant Left Hepatic Arteries Arising from Left Gastric Arteries and Their Clinical Importance. Surgeon 2020, 18, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi, R.; Randolph, J.; Cheruiyot, I.; Davies, J.R.; Wheeler, J.; Lancia, M.; Gioia, S.; Carlini, L.; di Saverio, S.; Henry, B.M. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Anatomical Variants of the Left Colic Artery. Color. Dis. 2020, 22, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi, R.; D’Andrea, V.; Lauro, A.; Renzi, C.; Henry, B.M.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Rende, M.; Lancia, M.; Carlini, L.; Gioia, S.; et al. The Absence of the Common Hepatic Artery and Its Implications for Surgical Practice: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surgeon 2019, 17, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi, R.; Randolph, J.; Cheruiyot, I.; Davies, R.J.; Wheeler, J.; Gioia, S.; Reznitskii, P.; Lancia, M.; Carlini, L.; Fedeli, P.; et al. Surgical Anatomy of Sigmoid Arteries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surgeon 2021, 19, e485–e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousek, M.; Whitley, A.; Kachlík, D.; Balko, J.; Záruba, P.; Belbl, M.; Nikov, A.; Ryska, M.; Gürlich, R.; Pohnán, R. The Dorsal Pancreatic Artery: A Meta-Analysis with Clinical Correlations. Pancreatology 2022, 22, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, G.; Belimezakis, N.; Lyros, O.; Węgiel, A.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Olewnik, Ł.; Tsakotos, G.; Zielinska, N.; Piagkou, M. Prevalence of Coeliac Trunk Variants: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2025, 259, 152385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, G.; Belimezakis, N.; Lyros, O.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Demetriou, F.; Tsakotos, G.; Piagkou, M. The Anatomy of the Inferior Mesenteric Artery: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2025, 47, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, G.; Lyros, O.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Kokoropoulos, P.; Demetriou, F.; Samolis, A.; Olewnik, Ł.; Landfald, I.C.; Piagkou, M. The Blood Supply of the Human Pancreas: Anatomical and Surgical Considerations. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, J.J.; Núñez-Castro, C.I.; Morán-Durán, V.B.; Nova-Baeza, P.; Orellana-Donoso, M.; Suazo-Santibáñez, A.; Becerra-Farfan, A.; Oyanedel-Amaro, G.; Bruna-Mejias, A.; Granite, G.; et al. Anatomical Variants in Pancreatic Irrigation and Their Clinical Considerations for the Pancreatic Approach and Surrounding Structures: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, A.; Oliverius, M.; Kocián, P.; Havlůj, L.; Gürlich, R.; Kachlík, D. Variations of the Celiac Trunk Investigated by Multidetector Computed Tomography: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis with Clinical Correlations. Clin. Anat. 2020, 33, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Mu, G.-C.; Qin, X.-G.; Chen, Z.-B.; Lin, J.-L.; Zeng, Y.-J. Study of Celiac Artery Variations and Related Surgical Techniques in Gastric Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 6944–6951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, G.C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.M.; Lin, J.L.; Zhang, L.L.; Zeng, Y.J. Clinical Research in Individual Information of Celiac Artery CT Imaging and Gastric Cancer Surgery. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 15, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelleyra Lastoria, D.A.; Smith, R.; Raison, N. Variations in the Origin of the Right Gastric Artery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2023, 45, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre, N.; Labrousse, M.; Magnan, P.E.; Branchereau, A.; Champsaur, P.; Bussani, R.; Braun, M.; Malikov, S. Surgical Anatomy of the Right Gastro-Omental Artery: A Study on 100 Cadaver Dissections. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2018, 40, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoun, L.; Breton, C.; Bors, V.; Helenon, C.; Bigot, J.M.; Parc, R. Radiological Anatomy of the Right Gastroepiploic Artery. Anat. Clin. 1984, 5, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, F.; Regoli, M.; Botta, G.; Bertelli, E. Right Gastroepiploic Artery Arising from the Dorsal Pancreatic Artery: A Very Rare Anatomic Variation Underlying Interesting Embryologic Implications. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2015, 37, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, C.; Kofopoulos-Lymperis, E.; Pikouli, A.; Lykoudis, P.; Pararas, N.; Papaconstantinou, D.; Nastos, C.; Myoteri, D.; Dellaportas, D. Gastric Conduit Reconstruction after Esophagectomy with Right Gastroepiploic Artery Absence: A Case Report. J. Surg. Case. Rep. 2023, 8, rjad474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelleyra Lastoria, D.A.; Benny, C.K. Variations in the Origin of the Infrapyloric Artery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2023, 249, 152109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, K.; Murakami, M.; Saito, A.; Ezure, H.; Moriyama, H.; Mori, R.; Otsuka, N. Anatomical and Surgical Evaluation of Gastroepiploic Artery. Okajimas Folia Anat. Jpn. 2016, 92, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Aithal, A.P.; Guru, A. Unusual Duplication and Vulnerable Intrapancreatic Course of the Left Gastroepiploic Artery: A Rare Anatomical Variation. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2019, 41, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wei, M.; Sun, D.; Zhong, X.; Liang, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, W. Study on the Application of Preoperative Three-Dimensional CT Angiography of Perigastric Arteries in Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikov, A.; Gürlich, R.; Kachlík, D.; Whitley, A. The Posterior Gastric Artery: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Clin. Anat. 2023, 36, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukas, M.; Wartmann, C.T.; Louis, R.G.; Tubbs, R.S.; Ona, M.; Curry, B.; Jordan, R.; Colborn, G.L. The Clinical Anatomy of the Posterior Gastric Artery Revisited. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2007, 29, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.R.; Charruf, A.Z.; Ramos, M.F.K.P.; Ribeiro, U.; Zilberstein, B.; Cecconello, I. D2 Lymphadenectomy According to the Arterial Variations in Gastric and Hepatic Irrigation. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 2879–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J. Anatomic Variations in the Left Gastric Vein and Their Clinical Significance during Laparoscopic Gastrectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2019, 33, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, G.; Wu, P.; Zhu, J.; Peng, W.; Xing, C. CT Imaging-Based Determination and Classification of Anatomic Variations of Left Gastric Vein. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2017, 39, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Xiong, W.; Luo, L.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, J.; Wan, J.; Xie, W.; Wang, W. Anatomical Observation and Clinical Significance of the Left Gastric Vein in Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy. J. Gastrointest. Oncol 2021, 12, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruna-Mejias, A.; Salgado-Torres, C.; Cáceres-Gálvez, C.; Rodriguez-Osorio, B.; Orellana-Donoso, M.; Nova-Baeza, P.; Suazo-Santibañez, A.; Oyanedel-Amaro, G.; Sanchis-Gimeno, J.; Piagkou, M.; et al. The Gastric Vein Variants: An Evidence-Based Systematic Review of Prevalence and Clinical Considerations. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Karcaaltincaba, M. Aberrant Left Gastric Vein Is Associated with Hepatic Artery Variations. Abdom. Radiol. 2019, 44, 3127–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caty, L.; Deneve, E.; Fontaine, C.; Guillem, P. Concurrent Aberrant Right Gastric Vein Directly Draining into the Liver and Variations of the Hepatic Artery. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2004, 26, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, T.W.; Chung, J.W.; Kim, H.-C.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, M.; Hur, S.; Jae, H.J. Aberrant Gastric Venous Drainage and Associated Atrophy of Hepatic Segment II: Computed Tomography Analysis of 2021 Patients. Abdom. Radiol. 2020, 45, 2764–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.-L.; Huang, C.-M.; Lu, J.; Zheng, C.-H.; Li, P.; Xie, J.-W.; Wang, J.-B.; Lin, J.-X.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Lin, M.; et al. The Impact of Confluence Types of the Right Gastroepiploic Vein on No. 6 Lymphadenectomy During Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy. Medicine 2015, 94, e1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Li, X.-X.; Xiang, N.; Zeng, N.; Fan, Y.-F.; Fang, C.-H. The Anatomy Features and Variations of the Point Where Right Gastroepiploic Vein Flows into Superior Mesenteric Vein/Portal Vein: Anatomical Study of Catheterization of Portal Vein Infusion Chemotherapy. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2018, 28, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumano, S.; Tsuda, T.; Tanaka, H.; Hirata, M.; Kim, T.; Murakami, T.; Sugihara, E.; Abe, H.; Yamashita, H.; Kobayashi, N.; et al. Preoperative Evaluation of Perigastric Vascular Anatomy by 3-Dimensional Computed Tomographic Angiography Using 16-Channel Multidetector-Row Computed Tomography for Laparoscopic Gastrectomy in Patients With Early Gastric Cancer. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2007, 31, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsume, T.; Shuto, K.; Yanagawa, N.; Akai, T.; Kawahira, H.; Hayashi, H.; Matsubara, H. The Classification of Anatomic Variations in the Perigastric Vessels by Dual-Phase CT to Reduce Intraoperative Bleeding during Laparoscopic Gastrectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2011, 25, 1420–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefura, T.; Kacprzyk, A.; Droś, J.; Pędziwiatr, M.; Major, P.; Hołda, M.K. The Venous Trunk of Henle (Gastrocolic Trunk): A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Its Prevalence, Dimensions, and Tributary Variations. Clin. Anat. 2018, 31, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaki, A.; Imamura, K.; Kobayashi, R.; Takami, M.; Matsumoto, J.; Takada, Y. Preoperative Assessment of Perigastric Vascular Anatomy by Multidetector Computed Tomography Angiogram for Laparoscopy-Assisted Gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2012, 397, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, E.C.; Verheij, M.; Allum, W.; Cunningham, D.; Cervantes, A.; Arnold, D. Gastric Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, v38–v49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songun, I.; Putter, H.; Kranenbarg, E.M.-K.; Sasako, M.; van de Velde, C.J. Surgical Treatment of Gastric Cancer: 15-Year Follow-up Results of the Randomised Nationwide Dutch D1D2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, R.; Inagawa, S.; Nagai, K.; Maeda, M.; Kemmochi, A.; Yamamoto, M. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Vascular Arrangement Including the Hepatic Artery and Left Gastric Vein during Gastric Surgery. Springerplus 2016, 5, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, D.M.; Roohipour, R. Bariatric Surgical Anatomy and Mechanisms of Action. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 21, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Wadden, T.A. Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.P.; Lee, S.R.; Nachiappan, A.C.; Willis, M.H.; Bray, C.D.; Farinas, C.A.; Whigham, C.J.; Spiegel, F. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Guide to Postoperative Anatomy and Complications. Abdom. Imaging 2011, 36, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.S.; Hess, D.W. Biliopancreatic Diversion with a Duodenal Switch. Obes. Surg. 1998, 8, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzara, C.; Osorio, J.; Valcarcel, J.; Pujol-Gebellí, J. Gastrointestinal Bleeding After Laparoscopic Duodenal Switch and SADI-S Caused by Pseudoaneurysm of Gastroduodenal Artery: First Reported Cases. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 3330–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esagian, S.M.; Ziogas, I.A.; Skarentzos, K.; Katsaros, I.; Tsoulfas, G.; Molena, D.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Rouvelas, I.; Nilsson, M.; Schizas, D. Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy versus Open Esophagectomy for Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, E.A.; Halle-Smith, J.M.; Kamarajah, S.K.; Evans, R.P.T.; Nepogodiev, D.; Hodson, J.; Bundred, J.R.; Gockel, I.; Gossage, J.A.; Isik, A.; et al. Predictors of Anastomotic Leak and Conduit Necrosis after Oesophagectomy: Results from the Oesophago-Gastric Anastomosis Audit (OGAA). Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 107983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-K.; Wang, Y.-J.; Zhang, T.-M.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.-L.; Chen, L.; Bao, T.; Zhao, X.-L.; Xie, X.-F.; Guo, W. Right Gastroepiploic Artery Length Determined Anastomotic Leakage after Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy for Esophageal Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 2757–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.-W.; Huang, P.-C.; Cheong, C.-F.; Chao, Y.-K.; Tsai, C.-Y. Restoring the Perfusion of Accidentally Transected Right Gastroepiploic Vessels during Gastric Conduit Harvest for Esophagectomy Using Microvascular Anastomosis: A Case Report and Literature Review. BMC Surg. 2022, 22, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Triantafyllou, G.; Lyros, O.; Schizas, D.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Demetriou, F.; Tsakotos, G.; Samolis, A.; Piagkou, M. The Blood Supply of the Stomach: Anatomical and Surgical Considerations. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222896

Triantafyllou G, Lyros O, Schizas D, Arkadopoulos N, Demetriou F, Tsakotos G, Samolis A, Piagkou M. The Blood Supply of the Stomach: Anatomical and Surgical Considerations. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(22):2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222896

Chicago/Turabian StyleTriantafyllou, George, Orestis Lyros, Dimitrios Schizas, Nikolaos Arkadopoulos, Fotis Demetriou, George Tsakotos, Alexandros Samolis, and Maria Piagkou. 2025. "The Blood Supply of the Stomach: Anatomical and Surgical Considerations" Diagnostics 15, no. 22: 2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222896

APA StyleTriantafyllou, G., Lyros, O., Schizas, D., Arkadopoulos, N., Demetriou, F., Tsakotos, G., Samolis, A., & Piagkou, M. (2025). The Blood Supply of the Stomach: Anatomical and Surgical Considerations. Diagnostics, 15(22), 2896. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222896