AI-Based Detection of Dental Features on CBCT: Dual-Layer Reliability Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Selection

- Inclusion criterion: A standardized large field-of-view of 10 × 13 cm was required to ensure full dentition coverage.

- Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of mixed dentition (both primary and permanent teeth). Patients with mixed dentition were excluded because the coexistence of primary and permanent teeth can confound automated tooth numbering. (2) CBCT scans with severe artifacts or overall poor image quality that would preclude a reliable diagnostic assessment.

2.3. Image Acquisition

2.4. AI Evaluation

2.5. Human Evaluation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Data Handling and Preparation

2.6.2. Tooth-Level Diagnostic Accuracy Analysis

2.6.3. Full-Scan Level Reliability Analysis

2.6.4. Sample Size Determination

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

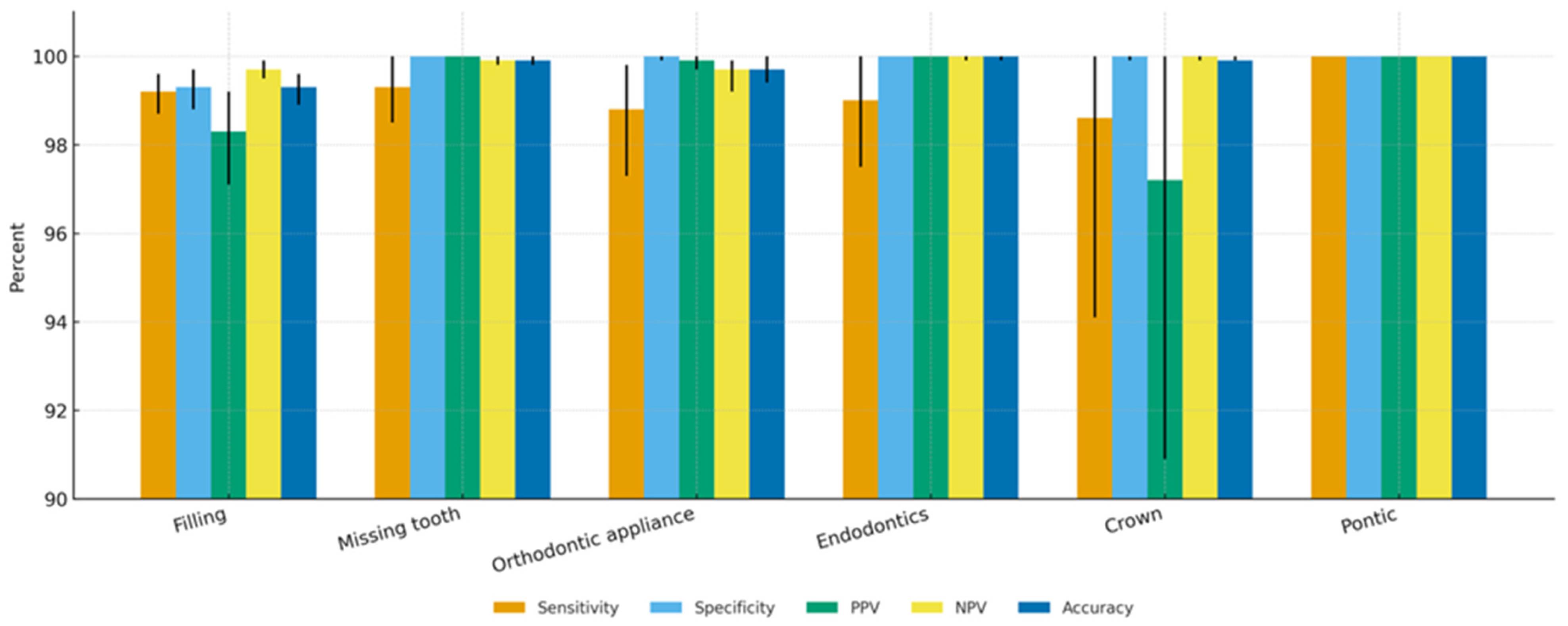

3.2. Tooth-Level Diagnostic Accuracy

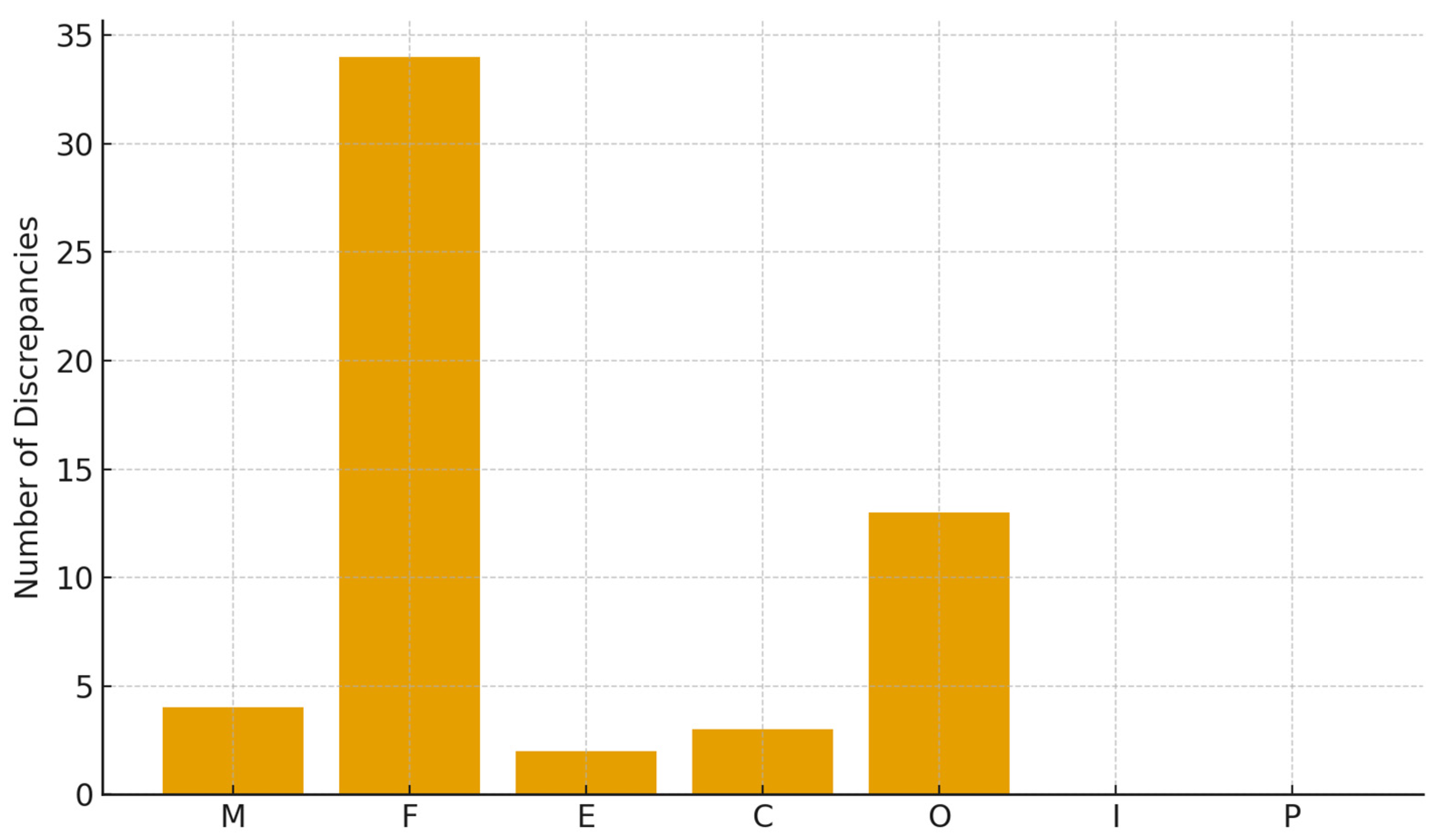

- Fillings: 34 discrepancies (60.7%);

- Orthodontic appliances: 13 discrepancies (23.2%).

- Missing teeth: 4 (7.1%);

- Crowns: 3 (5.4%);

- Endodontics: 2 (3.6%).

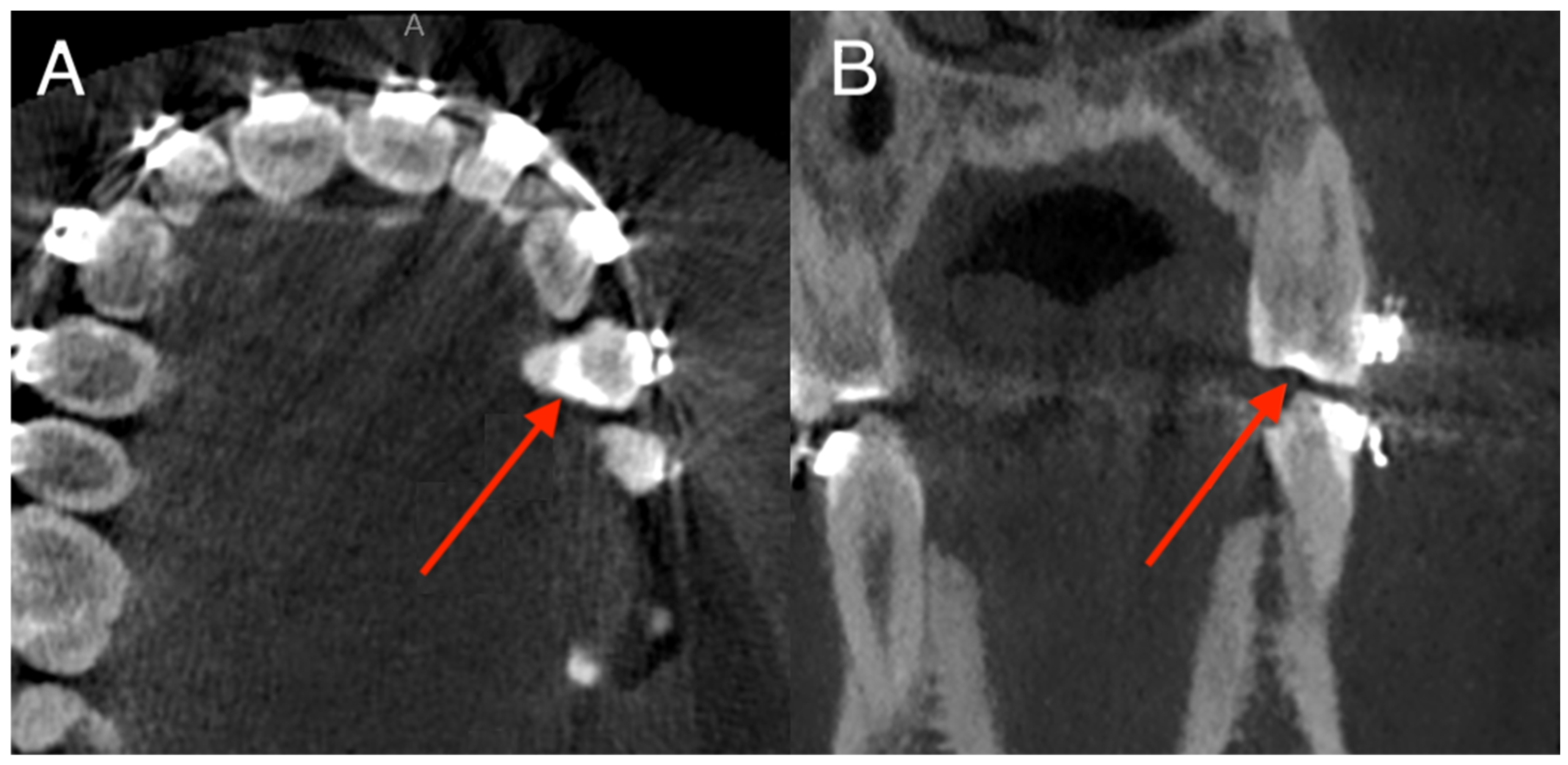

3.3. Anatomical Distribution of Errors

- Tooth 36: 6 errors (4.1% of patients);

- Tooth 27: 3 errors;

- Tooth 21, 11, 17, 14, 46, 38: isolated errors (1–2 cases).

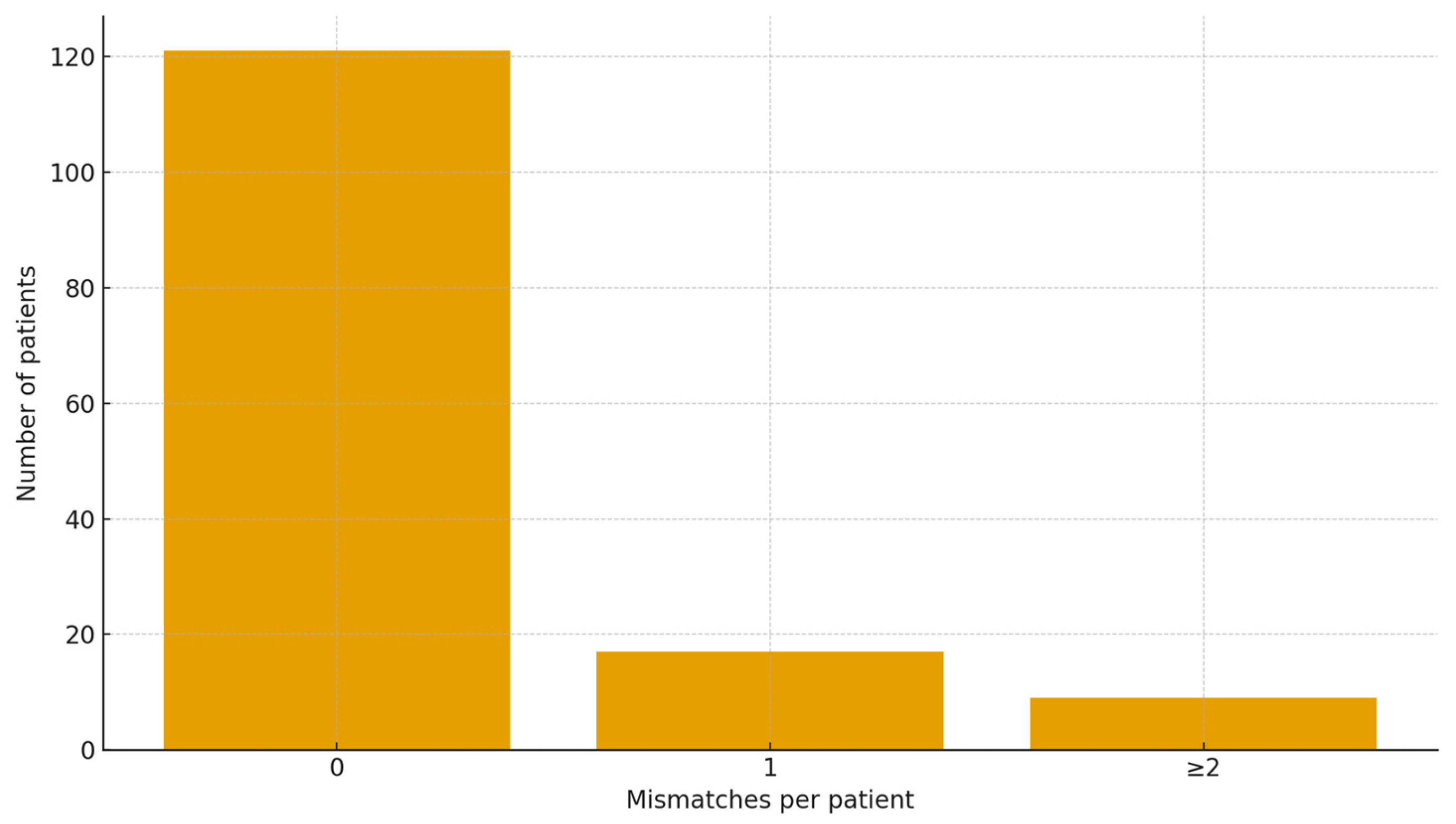

3.4. Full-Scan Level Diagnostic Accuracy

- False negative rate rose from 0.31 to 0.85% on single-finding teeth to ~2–3% on multi-finding teeth, depending on feature (e.g., Fillings 0.31% → 2.29%; Orthodontic appliances: 0.85% → 2.45%; Crowns: 0.00% → 2.78%; Endodontic treatment: 0.00% → 1.02%).

- Taxonomically, we observed 14 “omission on complex tooth” cases vs. 12 “omission on simple tooth”.

- The most frequent complex combo was Filling + Orthodontic appliance (n = 181 teeth); within these, the AI most often missed the filling (8 omissions) more than the appliance (3 omissions). For Endodontic treatment + Filling (n = 153), omissions were rare (1 endo miss). For Crown + Endodontic treatment (n = 21), sporadic misses occurred (1 endo, 1 crown).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| STARD | Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| OPG | Orthopantomogram |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FOV | Field of View |

| PAN | Panoramic Radiography |

References

- Venkatesh, E.; Elluru, S.V. Cone Beam Computed Tomography: Basics and Applications in Dentistry. J. Istanb. Univ. Fac. Dent. 2017, 51, S102–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarfe, W.C.; Farman, A.G. What Is Cone-Beam CT and How Does It Work? Dent Clin. N. Am. 2008, 52, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaêta-Araujo, H.; Leite, A.F.; de Faria Vasconcelos, K.; Jacobs, R. Two Decades of Research on CBCT Imaging in DMFR—An Appraisal of Scientific Evidence. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2021, 50, 20200367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlapati, K.; Gandhi Babu, D.B.; Chaitanya, N.C.S.K.; Guduru, H.; Rembers, A.; Soni, P. Evaluation of Preference and Purpose of Utilisation of Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Compared to Orthopantomogram (OPG) by Dental Practitioners—A Cross-Sectional Study. Pol. J. Radiol. 2017, 82, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccher, S.; Gowdar, I.M.; Guruprasad, Y.; Solanki, R.N.; Medhi, R.; Shah, M.J.; Mehta, D.N. CBCT: A Comprehensive Overview of Its Applications and Clinical Significance in Dentistry. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, S1923–S1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abesi, F.; Maleki, M.; Zamani, M. Diagnostic Performance of Artificial Intelligence Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Imaging of the Oral and Maxillofacial Region: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2023, 53, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, W.Y.; Au Yeung, S.Y.; Leung, Y.Y.; Leung, P.H.; Yang, W. Evolution of Deep Learning Tooth Segmentation from CT/CBCT Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.F.; Ai, Q.Y.H.; Leung, Y.Y.; Yeung, A.W.K. Potential and Impact of Artificial Intelligence Algorithms in Dento-Maxillofacial Radiology. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5535–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abesi, F.; Jamali, A.S.; Zamani, M. Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence in the Detection and Segmentation of Oral and Maxillofacial Structures Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pol. J. Radiol. 2023, 88, e256–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Yan, H.; Setzer, F.C.; Shi, K.J.; Mupparapu, M.; Li, J. Anatomically Constrained Deep Learning for Automating Dental CBCT Segmentation and Lesion Detection. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.F.; Yeung, A.W.K.; Bornstein, M.M.; Schwendicke, F. Personalized Dental Medicine, Artificial Intelligence, and Their Relevance for Dentomaxillofacial Imaging. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2023, 52, 20220335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploug, T.; Jørgensen, R.F.; Motzfeldt, H.M.; Ploug, N.; Holm, S. The Need for Patient Rights in AI-Driven Healthcare—Risk-Based Regulation Is Not Enough. J. R. Soc. Med. 2025, 118, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Barakat, M.; Sallam, M. A Preliminary Checklist (METRICS) to Standardize the Design and Reporting of Studies on Generative Artificial Intelligence–Based Models in Health Care Education and Practice: Development Study Involving a Literature Review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2024, 13, e54704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmi, M.; Atif, D.; Oliva, D.; Abraham, A.; Ventura, S. Handling Imbalanced Medical Datasets: Review of a Decade of Research. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkara, B.B.; Chen, M.M.; Federau, C.; Karabacak, M.; Briere, T.M.; Li, J.; Wintermark, M. Deep Learning for Detecting Brain Metastases on MRI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.; Lijmer, J.G.; Moher, D.; Rennie, D.; de Vet, H.C.W.; et al. STARD 2015: An Updated List of Essential Items for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Radiology 2015, 277, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn Buderer, N.M. Statistical Methodology: I. Incorporating the Prevalence of Disease into the Sample Size Calculation for Sensitivity and Specificity. Acad. Emerg. Med. 1996, 3, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, J.; Konwinska, M.D.; Kazimierczak, N.; Olszewski, R. Assessing the Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence in Mandibular Canal Segmentation Compared to Semi-Automatic Segmentation on Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Images. Pol. J. Radiol. 2025, 90, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, W.; Kazimierczak, N.; Issa, J.; Wajer, R.; Wajer, A.; Kalka, S.; Serafin, Z. Endodontic Treatment Outcomes in Cone Beam Computed Tomography Images—Assessment of the Diagnostic Accuracy of AI. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, S.; Wong, M.-C.; Yee, K.-C.; Turner, P. AI and Clinical Decision Making: The Limitations and Risks of Computational Reductionism in Bowel Cancer Screening. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T.M.; Andreotti, C.F.; Roberts, K.E.; Saracino, R.M.; Hernandez, M.; Basch, E. The Level of Association between Functional Performance Status Measures and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3645–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oerther, B.; Engel, H.; Bamberg, F.; Sigle, A.; Gratzke, C.; Benndorf, M. Cancer Detection Rates of the PI-RADSv2.1 Assessment Categories: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Lesion Level and Patient Level. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022, 25, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetstein, S.C.; Stathonikos, N.; Pluim, J.P.W.; Heng, Y.J.; ter Hoeve, N.D.; Vreuls, C.P.H.; van Diest, P.J.; Veta, M. Deep Learning-Based Grading of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ in Breast Histopathology Images. Lab. Investig. 2021, 101, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehman, E.C.; Behr, S.C.; Umetsu, S.E.; Fidelman, N.; Yeh, B.M.; Ferrell, L.D.; Hope, T.A. Rate of Observation and Inter-Observer Agreement for LI-RADS Major Features at CT and MRI in 184 Pathology Proven Hepatocellular Carcinomas. Abdom. Radiol. 2016, 41, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhov, M.; Gusarev, M.; Golitsyna, M.; Yates, J.M.; Kushnerev, E.; Tamimi, D.; Aksoy, S.; Shumilov, E.; Sanders, A.; Orhan, K. Clinically Applicable Artificial Intelligence System for Dental Diagnosis with CBCT. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allihaibi, M.; Koller, G.; Mannocci, F. The Detection of Apical Radiolucencies in Periapical Radiographs: A Comparison between an Artificial Intelligence Platform and Expert Endodontists with CBCT Serving as the Diagnostic Benchmark. Int. Endod. J. 2025, 58, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, W.; Wajer, R.; Wajer, A.; Kiian, V.; Kloska, A.; Kazimierczak, N.; Janiszewska-Olszowska, J.; Serafin, Z. Periapical Lesions in Panoramic Radiography and CBCT Imaging—Assessment of AI’s Diagnostic Accuracy. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzad, S.; Tabatabaei, S.M.H.; Lu, M.Y.; Eibschutz, L.S.; Gholamrezanezhad, A. Pitfalls in Interpretive Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Radiology. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2024, 223, e2431493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing tooth | 99.3% (98.5–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 99.9% (99.8–100.0%) | 99.9% (99.8–100.0%) | 99.7% (99.2–100.0%) |

| Filling | 99.2% (98.7–99.6%) | 99.3% (98.8–99.7%) | 98.3% (97.1–99.2%) | 99.7% (99.5–99.9%) | 99.3% (98.9–99.6%) | 98.7% (98.0–99.3%) |

| Endodontically treated tooth | 99.0% (97.5–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (99.9–100.0%) | 100.0% (99.9–100.0%) | 99.5% (98.7–100.0%) |

| Pontic | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) |

| Orthodontic appliance | 98.8% (97.3–99.8%) | 100.0% (99.9–100.0%) | 99.9% (99.7–100.0%) | 99.7% (99.2–99.9%) | 99.7% (99.4–100.0%) | 99.4% (98.6–99.9%) |

| Crown | 98.6% (94.1–100.0%) | 100.0% (99.9–100.0%) | 97.2% (90.9–100.0%) | 100.0% (99.9–100.0%) | 99.9% (99.9–100.0%) | 97.9% (93.7–100.0%) |

| Implant | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) | 100.0% (100.0–100.0%) |

| Criterion | Percent of Patients | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| 0 errors (Perfect Agreement) | 82.3% | 75.8–87.8% |

| ≤1 error | 91.8% | 87.1–96.0% |

| ≤2 errors | 94.6% | 90.5–98.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kazimierczak, N.; Sultani, N.; Chwarścianek, N.; Krzykowski, S.; Serafin, Z.; Ciszewska, A.; Kazimierczak, W. AI-Based Detection of Dental Features on CBCT: Dual-Layer Reliability Analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3207. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243207

Kazimierczak N, Sultani N, Chwarścianek N, Krzykowski S, Serafin Z, Ciszewska A, Kazimierczak W. AI-Based Detection of Dental Features on CBCT: Dual-Layer Reliability Analysis. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3207. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243207

Chicago/Turabian StyleKazimierczak, Natalia, Nora Sultani, Natalia Chwarścianek, Szymon Krzykowski, Zbigniew Serafin, Aleksandra Ciszewska, and Wojciech Kazimierczak. 2025. "AI-Based Detection of Dental Features on CBCT: Dual-Layer Reliability Analysis" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3207. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243207

APA StyleKazimierczak, N., Sultani, N., Chwarścianek, N., Krzykowski, S., Serafin, Z., Ciszewska, A., & Kazimierczak, W. (2025). AI-Based Detection of Dental Features on CBCT: Dual-Layer Reliability Analysis. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3207. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243207