Assessment of AI-Driven Large Language Models for Orthodontic Aesthetic Scoring Using the IOTN-AC

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Study Sample

2.2. Evaluation Procedure of AI-Based LLMs

2.3. Reference Evaluations by Clinicians

2.4. Data Analysis and Performance Metrics

- Comparison of the LLMs’ classification of each photograph with the reference classifications.

- Evaluation of the agreement between the AC scores (1–10) assigned by the LLMs and the reference scores.

- Assessment of the models’ classification performance using accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and specificity [11].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- •

- Although AI-based LLMs showed statistically significant and positive correlations with the reference IOTN-AC assessments, their current agreement levels remain insufficient for reliable clinical use.

- •

- The models exhibited variable performance across key evaluation metrics, indicating that consistent and high-level accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and precision have not yet been achieved.

- •

- Despite these limitations, the results demonstrate that LLMs possess notable potential. With targeted domain-specific fine-tuning and improved training strategies, these models may become valuable supportive tools in future orthodontic assessment workflows.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, D.G.; Sivamurthy, G.; Mossey, P. Helping General Dental Practitioners Use the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need: An Assessment of Available Educational Apps. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, W.; Richmond, S.; O’Brien, K. The Use of Occlusal Indices: A European Perspective. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1995, 107, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhammadi, M.S.; Halboub, E.; Fayed, M.S.; Labib, A.; El-Saaidi, C. Global Distribution of Malocclusion Traits: A Systematic Review. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2018, 23, 40.e1–40.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perillo, L.; Masucci, C.; Ferro, F.; Apicella, D.; Baccetti, T. Prevalence of Orthodontic Treatment Need in Southern Italian Schoolchildren. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzabadi-Farahani, A. An Insight into Four Orthodontic Treatment Need Indices. Prog. Orthod. 2011, 12, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, K.J.; Brook, K.J.; Thomson, W.M.; Harding, W.J. Factors Influencing Treatment Time in Orthodontic Patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 129, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patano, A.; Malcangi, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Garofoli, G.; De Leonardis, N.; Azzollini, D.; Latini, G.; Mancini, A.; Carpentiere, V.; Laudadio, C. Mandibular Crowding: Diagnosis and Management—A Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beglin, F.M.; Firestone, A.R.; Vig, K.W.; Beck, F.M.; Kuthy, R.A.; Wade, D. A Comparison of the Reliability and Validity of Three Occlusal Indexes of Orthodontic Treatment Need. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2001, 120, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, P.H.; Shaw, W.C. The Development of an Index of Orthodontic Treatment Priority. Eur. J. Orthod. 1989, 11, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, S.; Roberts, C.; Andrews, M. Use of the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN) in Assessing the Need for Orthodontic Treatment Pre- and Post-Appliance Therapy. Br. J. Orthod. 1994, 21, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.; Cicek, O.; Genç, Y.S. Can AI-Based ChatGPT Models Accurately Analyze Hand–Wrist Radiographs? A Comparative Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrygiannakis, M.A.; Giannakopoulos, K.; Kaklamanos, E.G. Evidence-Based Potential of Generative Artificial Intelligence Large Language Models in Orthodontics: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing. Eur. J. Orthod. 2024, cjae017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulou, E.; Moussiades, L. An Overview of Chatbot Technology. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, Neos Marmaras, Greece, 5–7 June 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Eggmann, F.; Weiger, R.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Blatz, M.B. Implications of Large Language Models Such as ChatGPT for Dental Medicine. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 35, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.S. Role of ChatGPT in Public Health. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 51, 868–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Dowling, P. A Survey of Undergraduate Orthodontic Training and Orthodontic Practices by General Dental Practitioners. J. Ir. Dent. Assoc. 2005, 51, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jackson, O.; Cunningham, S.; Moles, D.; Clark, J. Orthodontic Referral Behaviour of West Sussex Dentists. Br. Dent. J. 2009, 207, E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Ho-A-Yun, J.; McGuinness, N. Use and Knowledge of IOTN among GDPs in Scotland. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 218, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkan, S.; Pakshir, H.R.; Fattahi, H.R.; Oshagh, M.; Danaei, S.M.; Salehi, P.; Hedayati, Z. An Analytical Study on an Orthodontic Index: Index of Complexity, Outcome and Need (ICON). J. Dent. 2015, 16, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, S.; Ishigaki, K.; Lee, C.; Tanikawa, C.; Date, S.; Yoshikawa, T. Towards a Smart Dental Healthcare: An Automated Assessment of Orthodontic Treatment Need. HealthInfo 2017, 2017, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nandra, S.; Crawford, N.; Burford, D.; Pandis, N.; Cobourne, M.T.; Seehra, J. An Investigation into the Reliability of a Mobile App Designed to Assess Orthodontic Treatment Need and Severity. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 232, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Urbanova, W.; Novak, B.; Czako, L.; Siebert, T.; Stano, P.; Mareková, S.; Fountoulaki, G.; Fountoulaki, H.; Varga, I. Where Is the Artificial Intelligence Applied in Dentistry? Systematic Review and Literature Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirani, M.; Emami, M. Performance Comparison of Large Language Models in Treatment Planning for the Restoration of Endodontically Treated Teeth Over Time. J. Dent. 2025, 139, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajibagheri, P.; Sani, S.K.; Samami, M.; Tabari-Khomeiran, R.; Azadpeyma, K.; Sani, M.K. ChatGPT’s Accuracy in the Diagnosis of Oral Lesions. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Cai, G.; Guo, B.; Ma, L.; Shao, S.; Yu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, F. A Multi-Dimensional Performance Evaluation of Large Language Models in Dental Implantology: Comparison of ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Grok, Gemini and Qwen Across Diverse Clinical Scenarios. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir Cicek, B.; Cicek, O. Evaluating the Response of AI-Based Large Language Models to Common Patient Concerns About Endodontic Root Canal Treatment: A Comparative Performance Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.; Daniels, C.; Gilgrass, T. A Comparison of the Index of Complexity, Outcome and Need (ICON) with the Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) and the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN). Br. Dent. J. 2002, 193, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, F.A.N.M.; Ali, A.M.; Abd Rahman, A.N.A.; Zurin, M.A.M.; Salam, A.S.A.; Din, N.A.C. Classification of Malocclusion Using Convolutional Neural Network and Knowledge-Based Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 8th International Conference on Recent Advances and Innovations in Engineering (ICRAIE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2–3 December 2023; IEEE: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, A.R.; Beck, F.M.; Beglin, F.M.; Vig, K.W. Validity of the Index of Complexity, Outcome, and Need (ICON) in Determining Orthodontic Treatment Need. Angle Orthod. 2002, 72, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, J.W.; Vig, K.W.; Rinchuse, D.J.; Weyant, R.J. A Validation Study of Three Indexes of Orthodontic Treatment Need in the United States. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, S.; Kaboudan, A.; Talaat, W.; Kusnoto, B.; Sanchez, F.; Elnagar, M.H.; Bourauel, C.; Ghoneima, A. The Validity of an Artificial Intelligence Application for Assessment of Orthodontic Treatment Need from Clinical Images. Semin. Orthod. 2021, 27, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetzel, L.; Foucher, F.; Jang, S.J.; Wu, T.-H.; Fields, H.; Schumacher, F.; Richmond, S.; Ko, C.-C. Artificial Intelligence for Predicting the Aesthetic Component of the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LLMs | IOTN-AC | References | Cohen’s Kappa (%95–CI) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Need | Borderline Need | Definite Need | Total | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| GPT-5 Pro | No need | 36 (60) a | 22 (36.7) b | 2 (3.3) c | 60 (100) | 0.412 (0.292–0.517) | <0.001 * |

| Borderline need | 8 (17.8) a | 22 (48.9) b | 15 (33.3) a,b | 45 (100) | |||

| Definite need | 3 (6.7) a | 9 (20) a | 33 (73.3) b | 45 (100) | |||

| GPT-5 | No need | 35 (58.3) a | 23 (38.3) b | 2 (3.3) c | 60 (100) | 0.507 (0.396– 0.609) | <0.001 * |

| Borderline need | 0 (0) a | 26 (57.8) b | 19 (42.2) b | 45 (100) | |||

| Definite need | 1 (2.2) a | 5 (11.1) a | 39 (86.7) b | 45 (100) | |||

| LLMs | Treatment Need | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-5 Pro | No need | 60.0 | 87.8 | 76.6 | 60.7 |

| Borderline need | 48.9 | 70.5 | 41.5 | ||

| Definite need | 73.3 | 83.8 | 66.0 | ||

| GPT-5 | No need | 58.3 | 98.9 | 97.2 | 66.7 |

| Borderline need | 57.8 | 73.3 | 48.1 | ||

| Definite need | 86.7 | 80.0 | 65.0 |

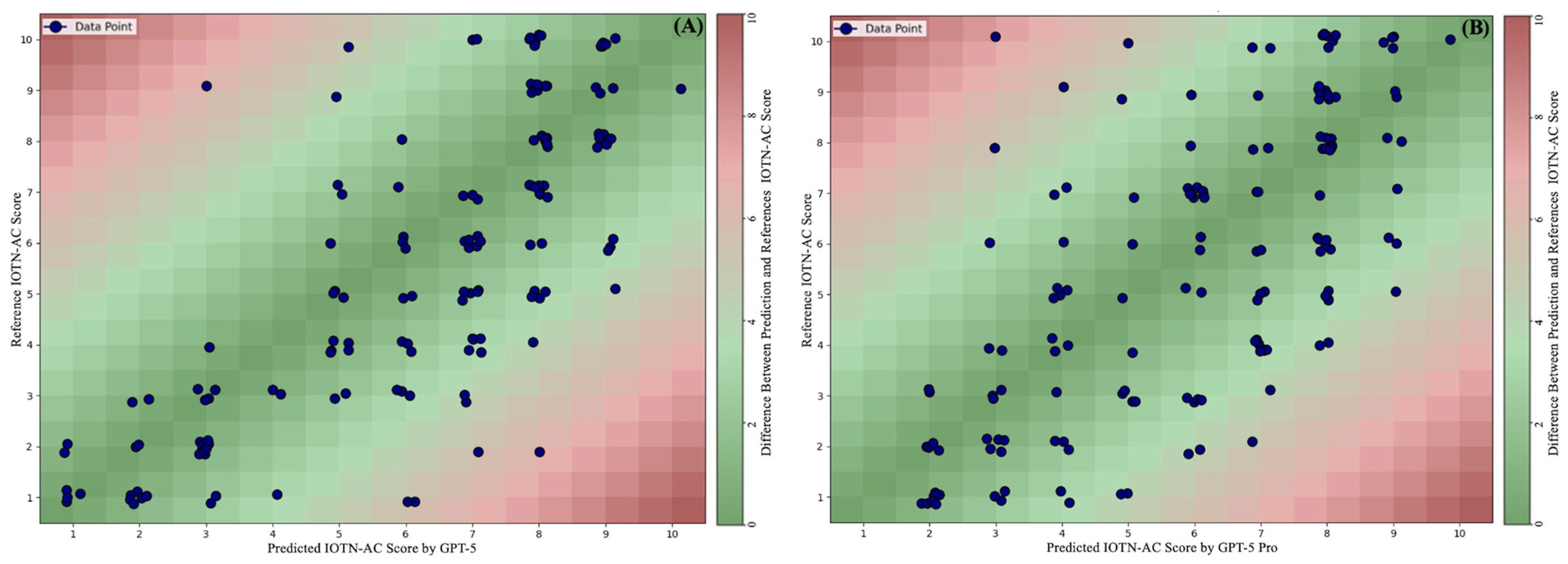

| Groups | References | GPT-5 Pro | GPT-5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | Spearman’s rho | 1 | 0.685 | 0.772 |

| p | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | ||

| GPT-5 Pro | Spearman’s rho | 1 | 0.868 | |

| p | <0.001 * | |||

| GPT-5 | Spearman’s rho | 1 | ||

| p |

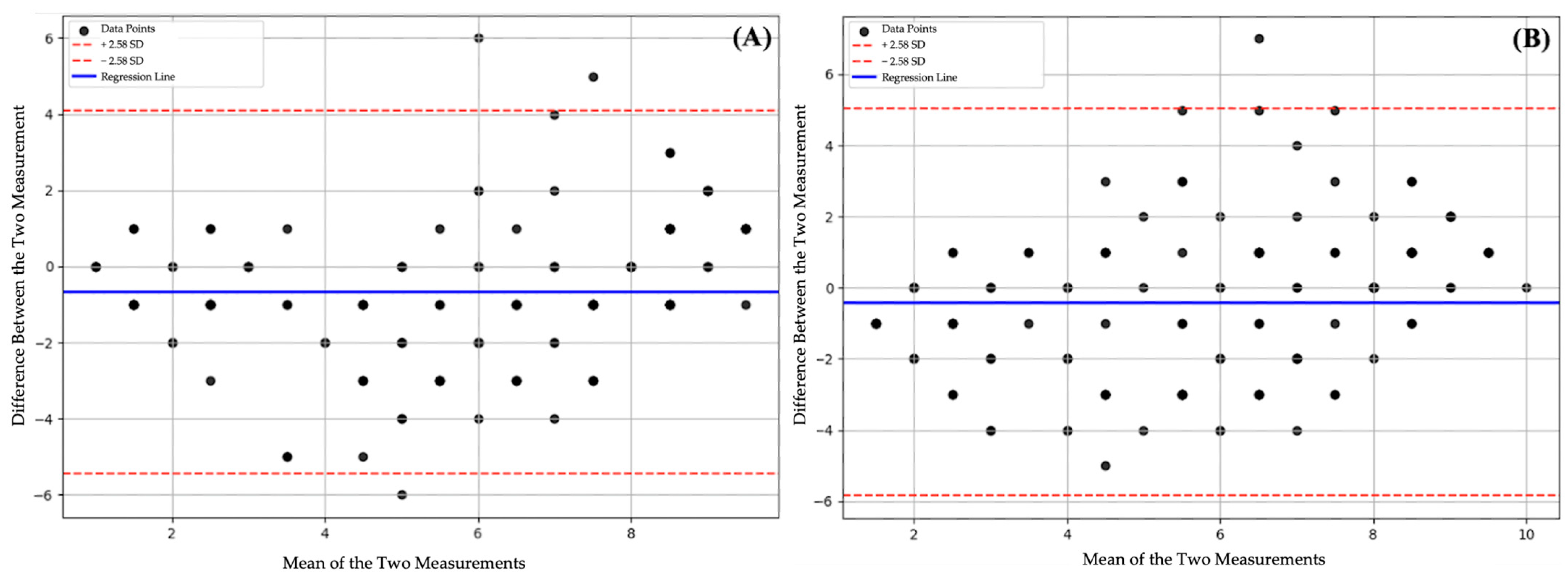

| LLMs | Cohen’s Kappa (Classification Agreement) | Spearman’s rho (Correlation of Scores) | MAE Mean ± SD (Median) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-5 Pro | 0.412 | 0.685 | 1.68 ± 1.34 (1.00) | 60.7 |

| GPT-5 | 0.507 | 0.772 | 1.47 ± 1.29 (1.00) | 66.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yıldırım, A.; Cicek, O. Assessment of AI-Driven Large Language Models for Orthodontic Aesthetic Scoring Using the IOTN-AC. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3048. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233048

Yıldırım A, Cicek O. Assessment of AI-Driven Large Language Models for Orthodontic Aesthetic Scoring Using the IOTN-AC. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3048. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233048

Chicago/Turabian StyleYıldırım, Ahmet, and Orhan Cicek. 2025. "Assessment of AI-Driven Large Language Models for Orthodontic Aesthetic Scoring Using the IOTN-AC" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3048. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233048

APA StyleYıldırım, A., & Cicek, O. (2025). Assessment of AI-Driven Large Language Models for Orthodontic Aesthetic Scoring Using the IOTN-AC. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3048. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233048