Hybrid 12-Month Exoskeleton Training with Percutaneous Epidural Stimulation After Spinal Cord Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Study Timeline

2.3. Temporary Implantation

2.4. Permanent Implantation

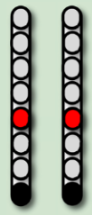

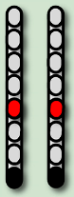

2.5. Spinal Mapping

2.6. Interventions

2.6.1. Exoskeleton-Assisted Walking (EAW)

2.6.2. Task-Specific Training

2.7. Statistical Analysis

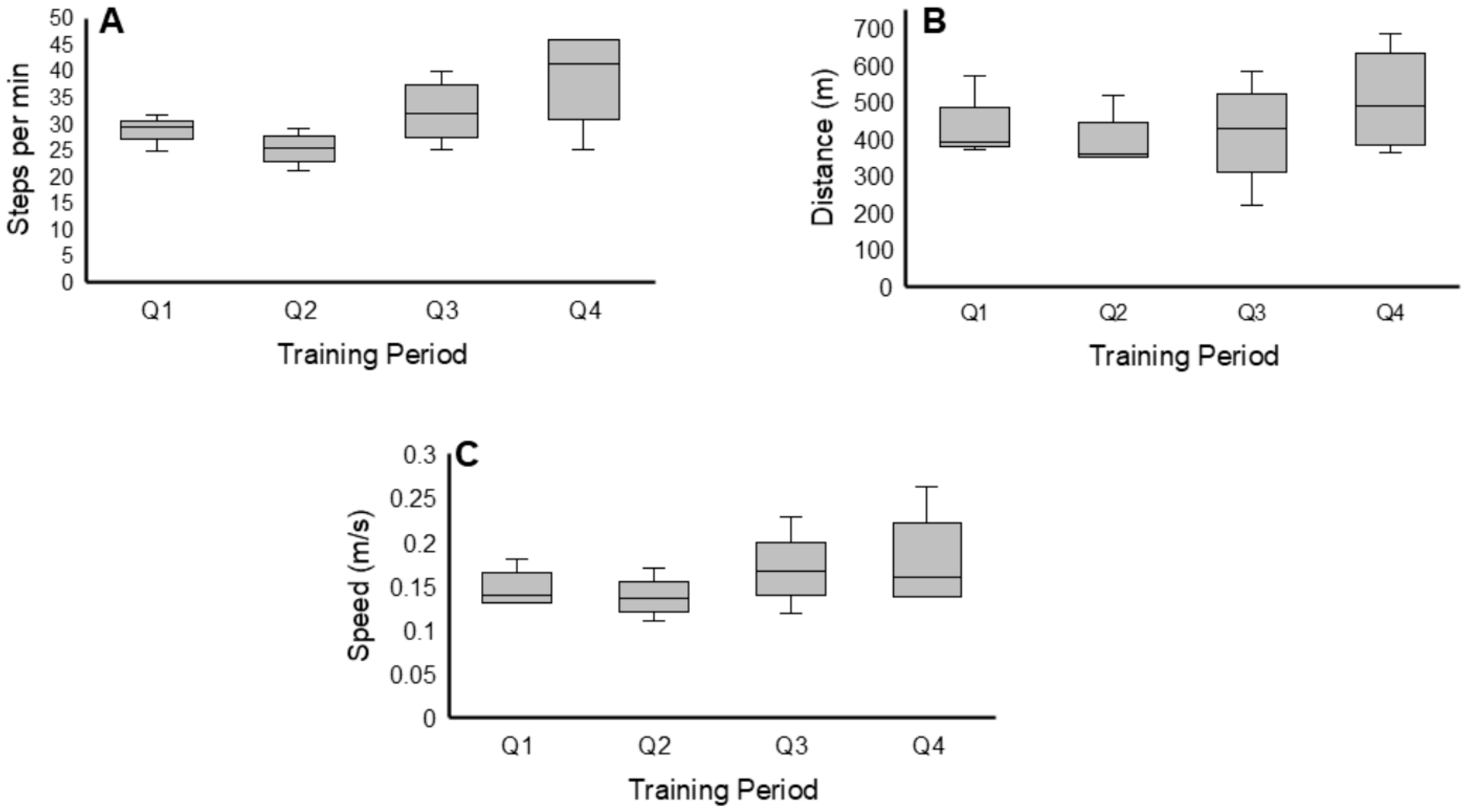

Exoskeleton Training Performance

3. Results

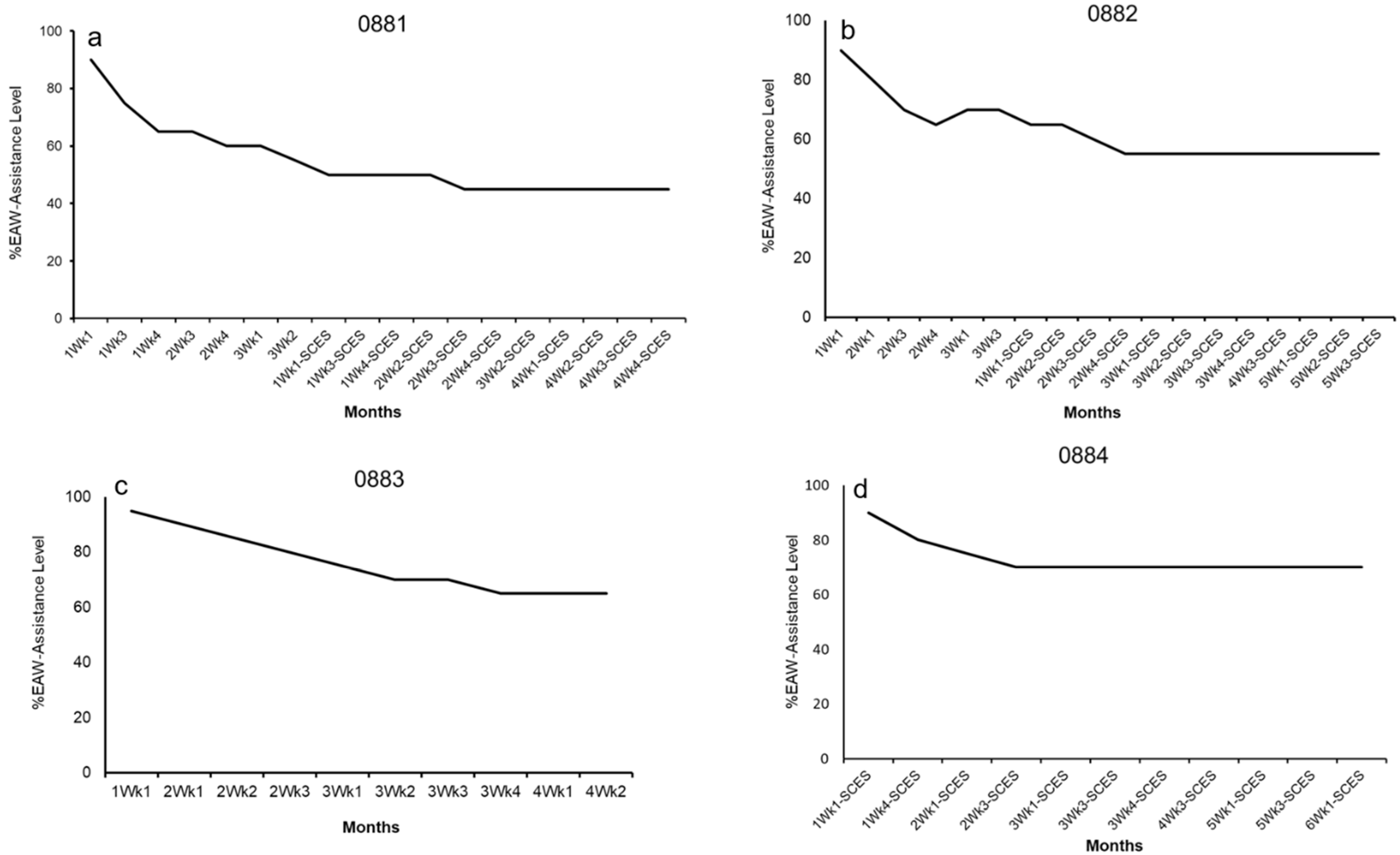

3.1. EAW Performance

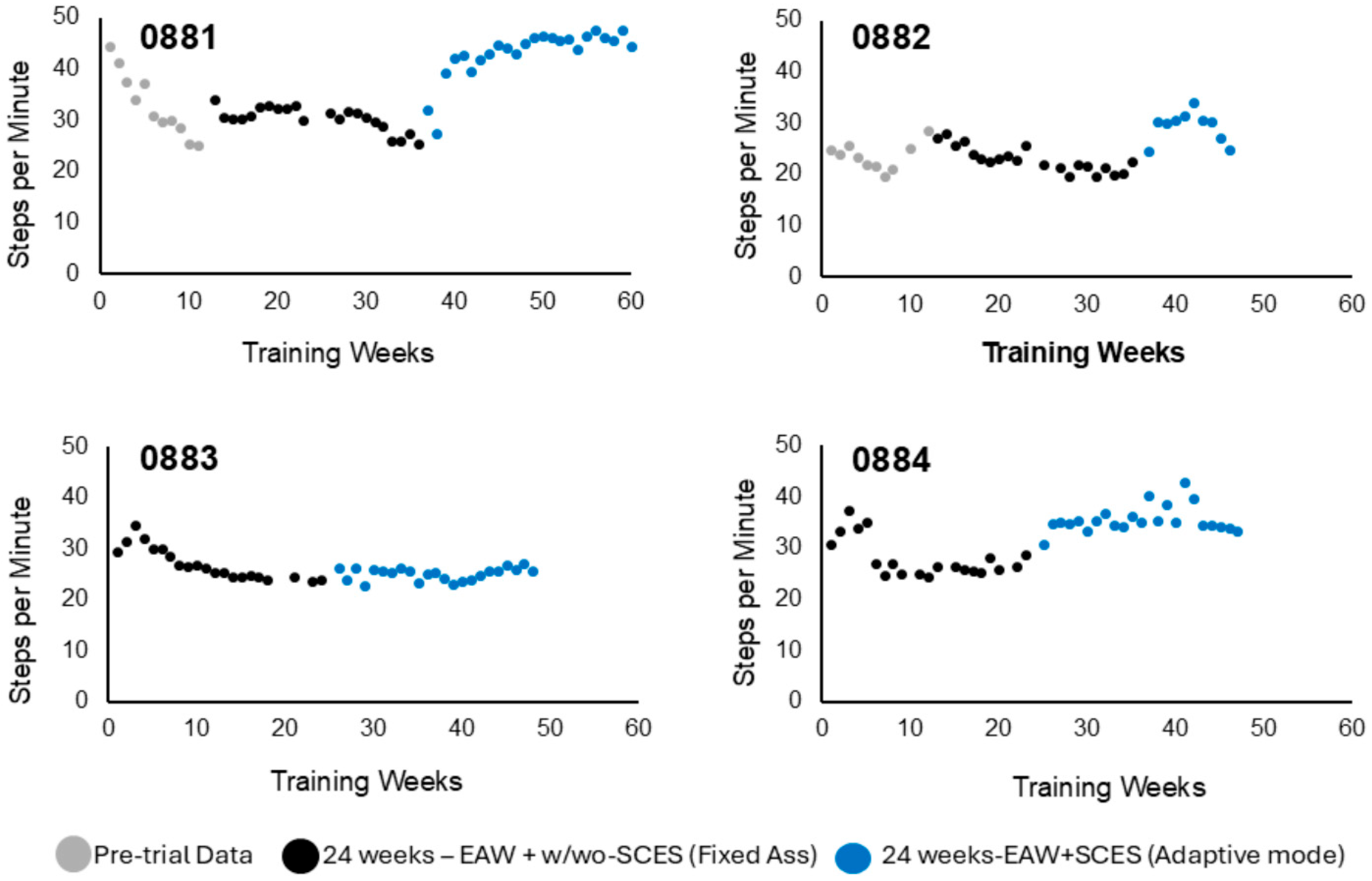

3.1.1. Steps per Minute

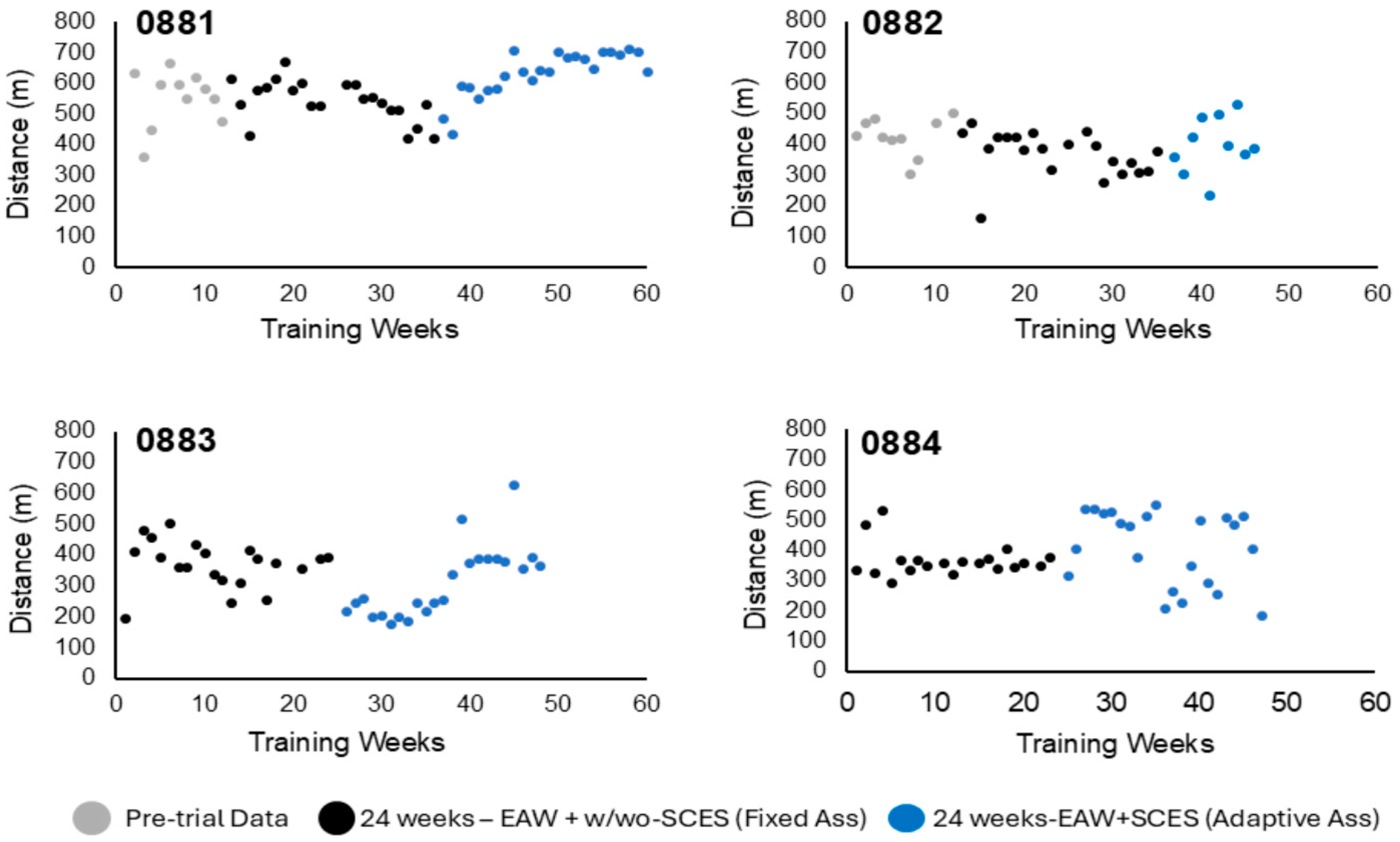

3.1.2. Walking Distance

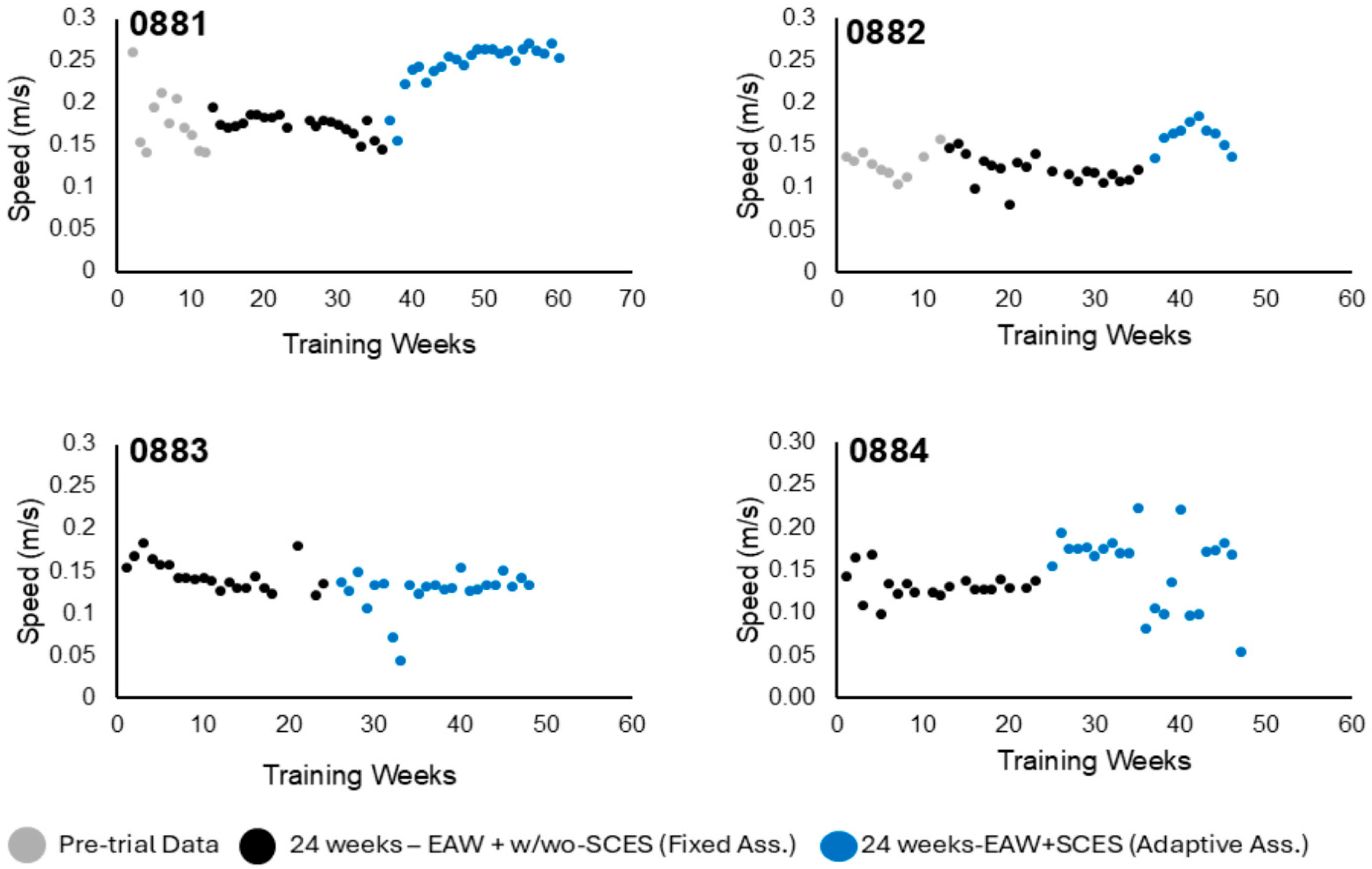

3.1.3. Walking Speed

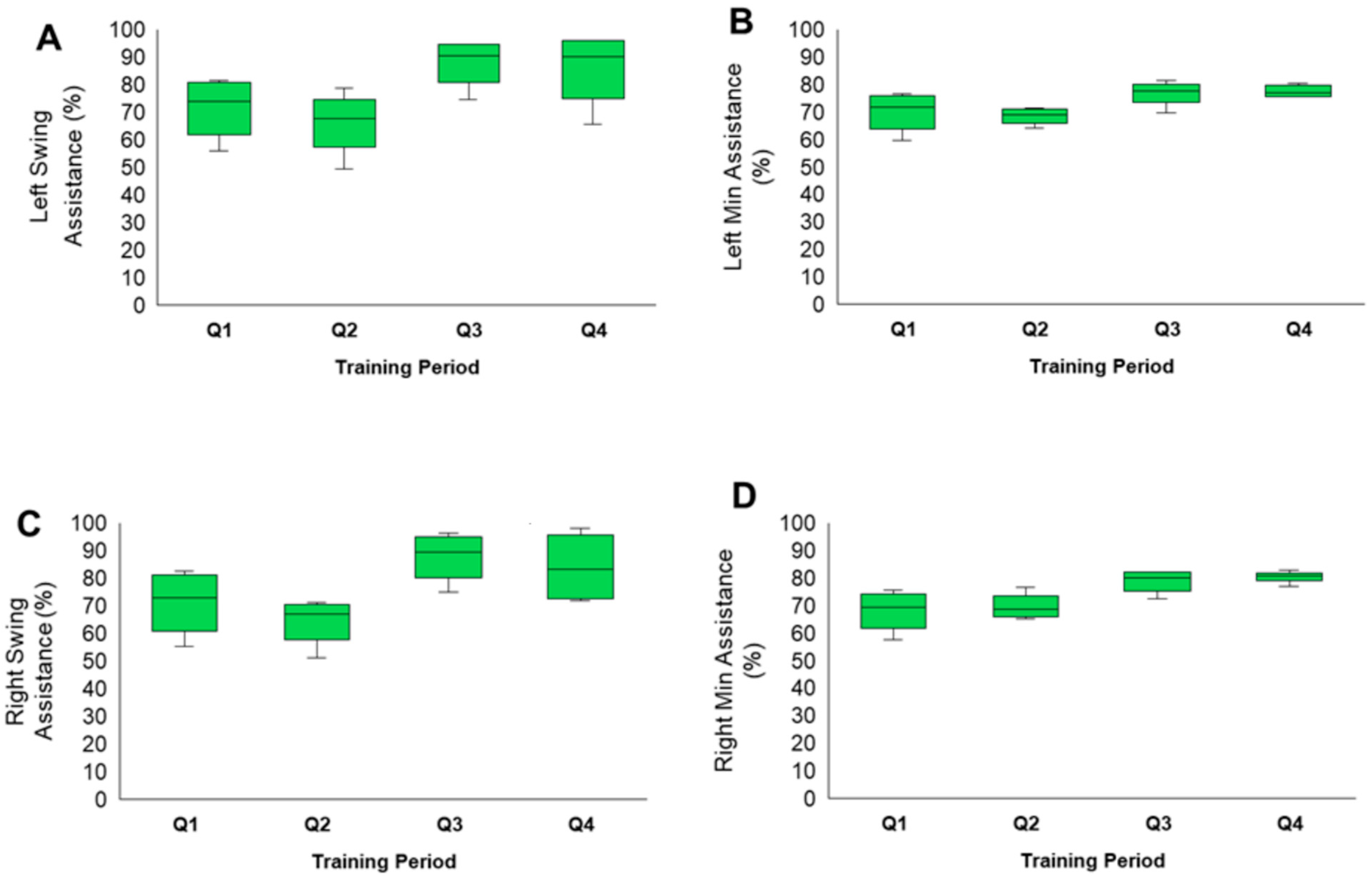

3.2. Exoskeleton Assistance

4. Discussion

4.1. EAW and Hybrid Application

4.2. EAW + SCES Application

4.3. Fixed vs. Adaptive-Assistance Mode in Association with SCES

4.4. EAW Metrics [Steps per Minute, Speed, and Distance]

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gorgey, A.S.; Sumrell, R.; Goetz, L.L. Exoskeletal assisted rehabilitation after spinal cord injury. In Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices, 5th ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Agudo, Á.; Megía-García, Á.; Pons, J.L.; Sinovas-Alonso, I.; Comino-Suárez, N.; Lozano-Berrio, V.; Del-Ama, A.J. Exoskeleton-based training improves walking independence in incomplete spinal cord injury patients: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Koyama, S.; Sakurai, H.; Teranishi, T.; Kanada, Y.; Tanabe, S. Wearable robotic exoskeleton for gait reconstruction in patients with spinal cord injury: A literature review. J. Orthop. Translat. 2021, 28, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spungen, A.M.; Dematt, E.J.; Biswas, K.; Jones, K.M.; Mi, Z.; Snodgrass, A.J.; Morin, K.; Asselin, P.K.; Cirnigliaro, C.M.; Kirshblum, S.; et al. Exoskeletal-Assisted Walking in Veterans with Paralysis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2431501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baunsgaard, C.B.; Nissen, U.V.; Brust, A.K.; Frotzler, A.; Ribeill, C.; Kalke, Y.-B.; León, N.; Gómez, B.; Samuelsson, K.; Antepohl, W.; et al. Gait training after spinal cord injury: Safety, feasibility and gait function following 8 weeks of training with the exoskeletons from Ekso Bionics. Spinal Cord 2018, 56, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, R.M.; Gorgey, A.S. Feasibility of robotic exoskeleton ambulation in a C4 person with incomplete spinal cord injury: A case report. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2018, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepertycky, M.; Burton, S.; Dickson, A.; Liu, Y.F.; Li, Q. Removing energy with an exoskeleton reduces the metabolic cost of walking. Science 2021, 372, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankov, N.; Caban, M.; Demesmaeker, R.; Roulet, M.; Komi, S.; Xiloyannis, M.; Gehrig, A.; Varescon, C.; Spiess, M.R.; Maggioni, S.; et al. Augmenting rehabilitation robotics with spinal cord neuromodulation: A proof of concept. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eadn5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanenko, Y.; Shapkova, E.Y.; Petrova, D.A.; Kleeva, D.F.; Lebedev, M.A. Exoskeleton gait training with spinal cord neuromodulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1194702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hai, M.; Feng, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, Z.; Duan, W. Exoskeleton-Assisted Rehabilitation and Neuroplasticity in Spinal Cord Injury. World Neurosurg. 2024, 185, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.J.; Forrest, G.; Cortes, M.; Weightman, M.M.; Sadowsky, C.; Chang, S.-H.; Furman, K.; Bialek, A.; Prokup, S.; Carlow, J.; et al. Walking improvement in chronic incomplete spinal cord injury with exoskeleton robotic training (WISE): A randomized controlled trial. Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Gill, S.; Holman, M.E.; Davis, J.C.; Atri, R.; Bai, O.; Goetz, L.; Lester, D.L.; Trainer, R.; Lavis, T.D. The feasibility of using exoskeletal-assisted walking with epidural stimulation: A case report study. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Trainer, R.; Khalil, R.E.; Deitrich, J.; Rehman, M.U.; Goetz, L.L.; Lester, D.; Klausner, A.; Peterson, C.L.; Lavis, T. Epidural Stimulation and Resistance Training (REST-SCI) for Overground Locomotion After Spinal Cord Injury: Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkelberger, N.; Berning, J.; Schearer, E.M.; O’Malley, M.K. Hybrid FES-exoskeleton control: Using MPC to distribute actuation for elbow and wrist movements. Front. Neurorobotics 2023, 17, 1127783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauffer, Y.; Allemand, Y.; Bouri, M.; Fournier, J.; Clavel, R.; Metrailler, P.; Brodard, R.; Reynard, F. The WalkTrainer--a new generation of walking reeducation device combining orthoses and muscle stimulation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2009, 17, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gad, P.; Gerasimenko, Y.; Zdunowski, S.; Turner, A.; Sayenko, D.; Lu, D.C.; Edgerton, V.R. Weight Bearing Over-ground Stepping in an Exoskeleton with Non-invasive Spinal Cord Neuromodulation after Motor Complete Paraplegia. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutor, T.W.; Ghatas, M.P.; Goetz, L.L.; Lavis, T.D.; Gorgey, A.S. Exoskeleton Training and Trans-Spinal Stimulation for Physical Activity Enhancement After Spinal Cord Injury (EXTra-SCI): An Exploratory Study. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 2, 789422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, K.; Hofstoetter, U.S. Spinal Cord Stimulation and Augmentative Control Strategies for Leg Movement after Spinal Paralysis in Humans. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016, 22, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, M.J.; White, J.M.; Stokic, D.S.; Tansey, K.E. Neuromodulation with transcutaneous spinal stimulation reveals different groups of motor profiles during robot-guided stepping in humans with incomplete spinal cord injury. Exp. Brain Res. 2023, 241, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Trainer, R.; Sutor, T.W.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Alazzam, A.; Goetz, L.L.; Lester, D.; Lavis, T.D. A case study of percutaneous epidural stimulation to enable motor control in two men after spinal cord injury. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alazzam, A.M.; Ballance, W.B.; Smith, A.C.; Rejc, E.; Weber, K.A.; Trainer, R.; Gorgey, A.S. Peak Slope Ratio of the Recruitment Curves Compared to Muscle Evoked Potentials to Optimize Standing Configurations with Percutaneous Epidural Stimulation after Spinal Cord Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venigalla, S.; Rehman, M.U.; Deitrich, J.N.; Trainer, R.; Gorgey, A.S. MRI Spinal Cord Reconstruction Provides Insights into Mapping and Migration Following Percutaneous Epidural Stimulation Implantation in Spinal Cord Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, V. Proprioception and locomotor disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copilusi, C.; Dumitru, S.; Dumitru, N.; Geonea, I.; Mic, C. An Exoskeleton Design and Numerical Characterization for Children with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Ko, L.-W.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-Y. Therapeutic Effects of Robotic-Exoskeleton-Assisted Gait Rehabilitation and Predictive Factors of Significant Improvements in Stroke Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Duan, W. Spatiotemporal spinal cord stimulation with real-time triggering exoskeleton restores walking capability: A case report. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025, 12, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieriacks, A.; Aach, M.; Brinkemper, A.; Koller, D.; Schildhauer, T.A.; Grasmücke, D. Rehabilitation of Acute Vs. Chronic Patients with Spinal Cord Injury with a Neurologically Controlled Hybrid Assistive Limb Exoskeleton: Is There a Difference in Outcome? Front. Neurorobotics 2021, 15, 728327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M.L.; Grahn, P.J.; Calvert, J.S.; Linde, M.B.; Lavrov, I.A.; Strommen, J.A.; Beck, L.A.; Sayenko, D.G.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Drubach, D.I.; et al. Neuromodulation of lumbosacral spinal networks enables independent stepping after complete paraplegia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, D.; Balser, D.; Netoff, T.I.; Krassioukov, A.; Phillips, A.; Parr, A.; Samadani, U. Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation Facilitates Immediate Restoration of Dormant Motor and Autonomic Supraspinal Pathways after Chronic Neurologically Complete Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, C.A.; Boakye, M.; Morton, R.A.; Vogt, J.; Benton, K.; Chen, Y.; Ferreira, C.K.; Harkema, S.J. Recovery of Over-Ground Walking after Chronic Motor Complete Spinal Cord Injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlgren, C.; Levi, R.; Amezcua, S.; Thorell, O.; Thordstein, M. Prevalence of discomplete sensorimotor spinal cord injury as evidenced by neurophysiological methods: A cross-sectional study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 53, jrm00156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Sex | Age (year) | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI (kg/m2) | TSI (year) | NLI | AIS | Classification | Level of Ekso. Ass. | Assistive Device | Weeks Attained ** | Amp (mA)-First 6 Month | Amp (mA)-Last 6 Month | MAS at the Time of Admission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0881 | M | 25 | 48.6 | 174.3 | 16.0 | 6.0 | C8 | A | Tetraplegia | 45% | Canadian crutches | 8 | 1.1–6 | 4.6 | 1+−3 |

| 0082 | M | 36 | 99.4 | 182.2 | 29.9 | 9.0 | T11 | B | Paraplegia | 50% | Canadian crutches | 13 | 1.6–2.7 | 2–4 | 2 |

| 0883 | M | 38 | 99.0 | 180.5 | 30.4 | 12.0 | T6 | A | Paraplegia | 70% | Standard roller walker | 9 | No SCES | 7 | 1–2 |

| 0884 * | M | 54 | 93.4 | 182.8 | 28.0 | 24.0 | T4 | A | Paraplegia | 70% | Standard roller walker/Canadian crutches | 7 | 6–8 | 7.9 | 0–2 |

| Assessment Period and Mapping | Training | Assessment Period and Mapping | Training | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Events | Baseline Ass. | Temporary Implantation and Mapping | Permanent Implant | Resting Period | Mapping | Training Phase 1 | P1 Ass. | Interim Mapping | Permanent Implant | Resting Period | Mapping | Training Phase 2 | Training Phase 2 | P2 Ass |

| Group 1 [EAW + SCES + RT] | 1 week | 3–5 days | Three weeks Later | Three weeks to avoid migration | 2–3 weeks | 1 h EAW + SCES for 24 weeks + 1 h of task-specific training (sit-to-stand activity) for 24 weeks | 1 week | 3 weeks | Completed in Phase 1 | Completed in Phase 1 | Completed in Phase 1 | 1 h EAW + SCES for 12 weeks + 1 h of task-specific training (sit-to-stand activity) for 12 weeks + 12 weeks of NMES-RT | 1 h EAW + SCES for 12 weeks + 1 h of task-specific training (sit-to-stand activity) for 12 weeks + 12 weeks of closed-chain RT using SCES | 1 week |

| Group 2 [EAW+ delayed SCES + noRT] | 1 week | 3–5 days | Delayed implantation to the second phase of the trial | Not applicable | Not applicable | 1 h EAW only for 24 weeks | 1 week | Not applicable | After P1 | Three weeks to avoid migration | 2–3 weeks | 1 h EAW + SCES for 12 weeks + 1 h of task-specific training (sit-to-stand activity) for 12 weeks + 12 weeks of PMT | 1 h EAW + SCES for 12 weeks + 1 h of task-specific training (sit-to-stand activity) for 12 weeks | 1 week |

| 3 days per week | 3–5 days per week | |||||||||||||

| Weeks | Week 1 | Previously completed prior to BL assessment | Week 2–25 | Week 26 | Week 27–29 | Week 30–41 | Week 42–53 | Week 54 | ||||||

| Weeks | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4–6 | Week 7–9 | Week 10–33 | Week 34 | Week 35–37 | Week 38–49 | Week 50–61 | Week 62 | |||

| Weeks | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3–26 | Week 27 | Week 28 | Week 31 | Week 32–35 | Week 36–47 | Week 48–59 | Week 60 | ||||

| Two phases |  |  | ||||||||||||

| 0881 | 0882 | 0883 | 0884 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAW Training Phase 1 (24 weeks) |  |  | No SCES |  |

| Configurations | ||||

| Stimulation Parameters | 1.7–3.5 mA, 350–450 µs, 25 Hz | 1.6–2.3 mA, 350–450 µs, 20 Hz | 6–8 mA, 210 µs, 40 Hz | |

| EAW Training Phase 2 (24 weeks) | ||||

| Configurations |  |  |  |  |

| Stimulation Parameters | 3.0 mA, 250 µs, 25 Hz | 3.5 mA, 250 µs, 30 Hz | 7 mA, 300 µs, 60 Hz, | 6–8 mA, 210 µs, 40 Hz |

| Participant ID | Number of Weeks (48 Weeks) | Missed Weeks | Up Time (min) | Walk Time (min) | % Walk Time to up Time | Number of Steps | Distance (m) | Speed (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0881 | 46 | 2 | 66 ± 7 | 47 ± 5.7 | 72 ± 4.5 | 1727 ± 243 | 592 ± 83 | 0.21 ± 0.04 |

| 0882 | 31 | 17 * | 65 ± 14.5 | 48 ± 19.0 | 74 ± 9.0 | 1151 ± 238 | 380 ± 78.5 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| 0883 | 44 | 4 | 56 ± 13.5 | 42 ± 11.0 | 74 ± 7.0 | 1074 ± 319 | 341 ± 101 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| 0084 | 43 | 5 | 56 ± 6.0 | 45 ± 5.0 | 81 ± 4.0 | 1308 ± 328 | 392 ± 98 | 0.15 ± 0.04 |

| Average | 41 ± 7.0 | 3.7 ± 2.0 | 61 ± 6.0 | 46 ± 3.0 | 75 ± 4.0 | 1315 ± 291 | 426 ± 113 | 0.16 ± 0.04 |

| Participant ID | Number of Weeks | Up Time (min) | Walk Time (min) | % Walk Time to up Time | Number of Steps | Distance (m) | Speed (m/s) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAW Ass. Mode | Fixed | Adap. | Fixed | Adap. | Fixed | Adap. | Fixed | Adap. | Fixed | Adap. | Fixed | Adap. | Fixed | Adap. |

| 0881 | 21 | 25 | 70 ± 8 | 62 ± 2 * | 52 ± 5 | 43 ± 2 * | 74 ± 5 | 70 ± 3 * | 1604 ± 183 | 1830 ± 242 * | 550 ± 63 | 627 ± 83 * | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.04 * |

| 0882 | 21 | 10 | 70 ± 14 | 56 ± 11 * | 52 ± 12 | 42 ± 9 * | 74 ± 10 | 74 ± 10 | 1122 ± 218 | 1213 ± 277 | 370 ± 72 | 400 ± 91 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 * |

| 0883 | 20 | 24 | 58 ± 9 | 55 ± 16 | 42 ± 8 | 42 ± 13 | 72 ± 9 | 76 ± 6 | 1167 ± 244 | 996 ± 357 x | 371 ± 77 | 316 ± 113 x | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 * |

| 0084 | 20 | 23 | 59 ± 5 | 54 ± 6 * | 46 ± 3 | 45 ± 6 | 79 ± 4 | 82 ± 4 * | 1229 ± 182 | 1376 ± 408 * | 369 ± 55 | 413 ± 123 x | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.04 * |

| Average | 20.5 ± 1 | 20.5 ± 7 | 64 ± 7 | 57 ± 4 | 48 ± 5 | 43 ± 1 | 75 ± 3 | 76 ± 5 | 1281 ± 220 | 1354 ± 353 | 415 ± 90 | 439 ± 133 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Deitrich, J.N.; Rehman, M.U.; Trainer, R.; Cifu, D.X.; Gorgey, A.S. Hybrid 12-Month Exoskeleton Training with Percutaneous Epidural Stimulation After Spinal Cord Injury. Life 2026, 16, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010077

Deitrich JN, Rehman MU, Trainer R, Cifu DX, Gorgey AS. Hybrid 12-Month Exoskeleton Training with Percutaneous Epidural Stimulation After Spinal Cord Injury. Life. 2026; 16(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeitrich, Jakob N., Muhammad Uzair Rehman, Robert Trainer, David X. Cifu, and Ashraf S. Gorgey. 2026. "Hybrid 12-Month Exoskeleton Training with Percutaneous Epidural Stimulation After Spinal Cord Injury" Life 16, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010077

APA StyleDeitrich, J. N., Rehman, M. U., Trainer, R., Cifu, D. X., & Gorgey, A. S. (2026). Hybrid 12-Month Exoskeleton Training with Percutaneous Epidural Stimulation After Spinal Cord Injury. Life, 16(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010077