Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Diabetes Mellitus: An Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Significance

Theoretical Framework

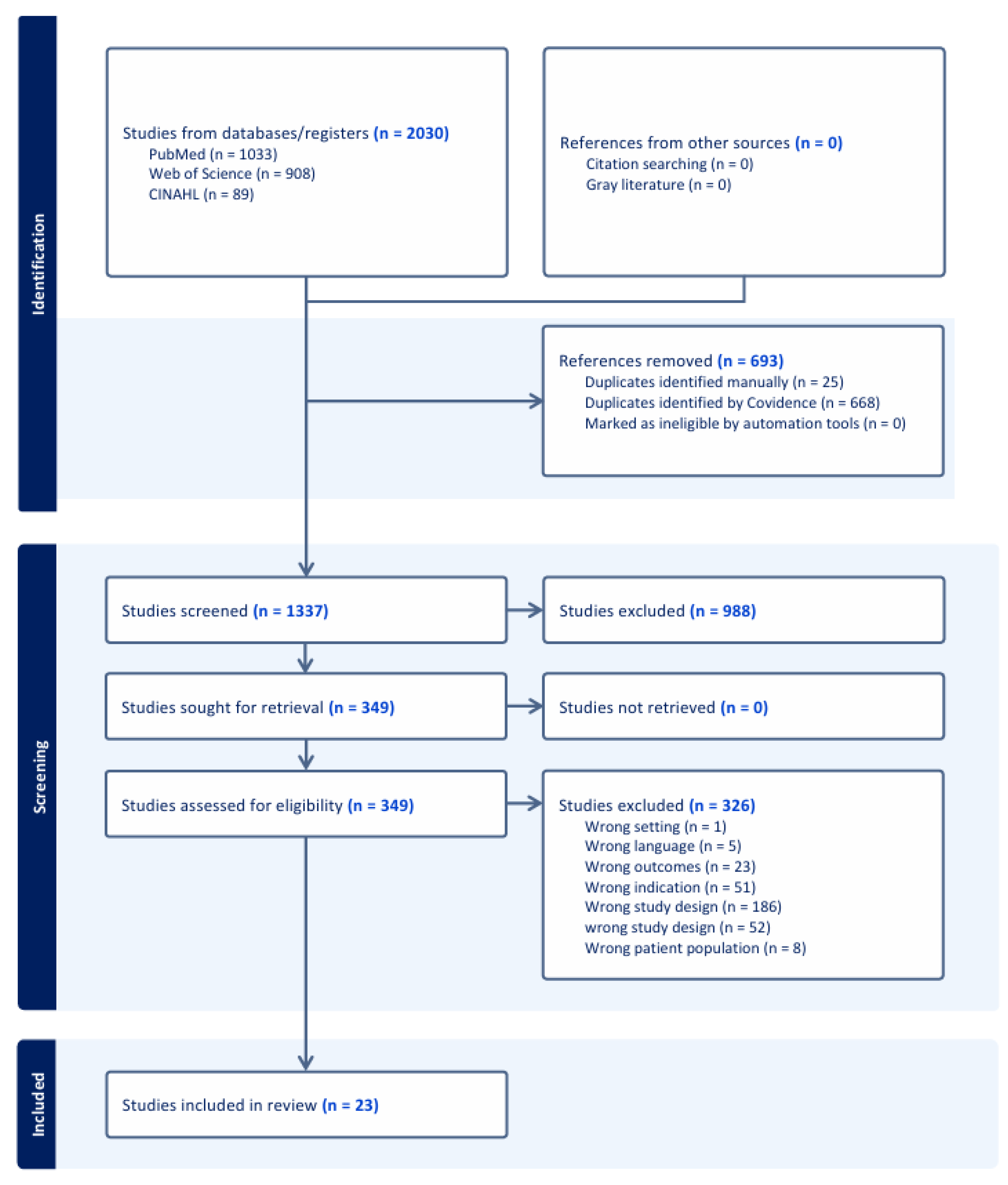

3. Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Searches

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4. Results

4.1. Study Characteristics

4.1.1. Host Characteristics

4.1.2. Agent Characteristics

4.1.3. Micro-Environment Characteristics

HLA-Expression and T-Cell Upregulation

Pancreatic Autoantibodies

5. Discussion

Strengths and Weakness

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NR | NR-Not Reported |

| CA | Cancer |

| ICI | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4 |

| MM | Multiple Myeloma |

| SCLS | Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| SCC | Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| ATC | Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| H&N | Head and Neck |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| Chemo | Chemotherapy |

| RCC | Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| IAA | Insulin Autoantibodies |

| GAD65 | Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase 65 |

| IA-2 | Islet Antigen-2 |

| ZnT8 | Zinc Transporter 8 |

| Pre-DM | Pre-Diabetes Mellitus |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| PMH | Past Medical History |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| ICI-DM | Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor diabetes mellitus |

| RA | Retrospective Analysis |

| PA | Prospective Analysis |

| W | Weeks |

| M | Months |

| D | Days |

| C | Cycles |

| T1DM | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| NR | Not Reported |

| CC | Conventional Chemotherapy |

| PTS | Patients |

| irAE | Immune-Mediated Adverse Effects |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| ICI-IAD- | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Isolated Adrenocorticotropic Hormone Deficiency |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| MESH | Medical Subject Headings |

References

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. World Health Organization Web Site. Updated 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Zorena, K.; Michalska, M.; Kurpas, M.; Jaskulak, M.; Murawska, A.; Rostami, S. Environmental Factors and the Risk of Developing Type 1 Diabetes—Old Disease and New Data. Biology 2022, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, N.G.; Nepom, G.T. Prediction and Pathogenesis in Type 1 Diabetes. Immunity 2011, 32, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.K.; Jung, C.H. Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors-Induced Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: From Its Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Practice. Diabetes Metab. J. 2023, 47, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filette, J.M.K.; Pen, J.J.; Decoster, L.; Vissers, T.; Bravenboer, B.; Van der Auwera, B.J.; Gorus, F.K.; O Roep, B.; Aspeslagh, S.; Neyns, B.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and type 1 diabetes mellitus: A case report and systematic review. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Affinati, A.H.; Lee, Y.; Turcu, A.F.; Henry, N.L.; Schiopu, E.; Qin, A.; Othus, M.; Clauw, D.; Ramnath, N.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Risk of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, S.; Hirokazu, H.; Yamagishi, K.; Hideki, S.; Masayuki, E. Predictors of the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes Obtained from Real-World Data Analysis in Cancer Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tsang, V.H.M.; Sasson, S.C.; Menzies, A.M.; Carlino, M.S.; Brown, D.A.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Gunton, J.E. Unravelling Checkpoint Inhibitor Associated Autoimmune Diabetes: From Bench to Bedside. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 764138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergès, B. Diabetes Induced by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs). Ann. D’endocrinologie 2023, 84, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstone, M.; Rewegan, A.; Brundisini, F.; Dejean, D.; Giacomini, M. Patient perspectives on quality of life with uncontrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2015, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. New American Diabetes Association Report Finds Annual Costs of Diabetes to be $412.9 Billion. 1 November 2023. Available online: https://diabetes.org/newsroom/press-releases/new-american-diabetes-association-report-finds-annual-costs-diabetes-be (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Zhu, J.; Luo, M.; Liang, D.; Gao, S.; Zheng, Y.; He, Z.; Zhao, W.; Yu, X.; Qiu, K.; Wu, J. Type 1 diabetes with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic analysis of clinical trials and a pharmacovigilance study of postmarketing data. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 110, 109053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Esteves, K.N.; Shank, K.R.; Deutsch, A.J.; Gunturi, A.; Chamorro-Pareja, N.; Colling, C.A.; Zubiri, L.; Perlman, K.; Ouyang, T.; Villani, A.-C.; et al. Identification of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Induced Diabetes. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snieszko, S.F. The effects of environmental stress on outbreaks of infectious diseases of fishes. J. Fish Biol. 1974, 6, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Seventer, J.M.; Hochberg, N.S. Principles of infectious diseases: Transmission, diagnosis, prevention, and control. Int. Encycl. Public Health 2017, 22-39, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Carlino, M.S.; Brown, D.A.; Long, G.V.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Mellor, R.; Moore, K.; Sasson, S.C.; Menzies, A.M.; Tsang, V.; et al. Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Autoimmune Diabetes Mellitus Is Characterized by C-peptide Loss and Pancreatic Atrophy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: CASP Cohort Study Checklist. Web Site. Updated 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. Web Site. Updated 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/qualitative-studies-checklist/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: CASP Systematic Review Checklist. Web Site. Updated 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Web Site. Updated 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/systematic-review-checklist/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Grima, L.; Hammerbeck, U. Quality appraisal results using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Cohort Studies checklist. Zenodo. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Basak, E.A.; De Joode, K.; Uyl, T.J.J.; van der Wal, R.; Schreurs, M.W.; Berg, S.A.v.D.; Hoop, E.O.-D.; van der Leest, C.H.; Chaker, L.; Feelders, R.A.; et al. The course of C-peptide levels in patients developing diabetes during anti-PD-1 therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Jeong, K.; Park, Y.R.; Rhee, Y. Increased risk of incident diabetes after therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitor compared with conventional chemotherapy: A longitudinal trajectory analysis using a tertiary care hospital database. Metabolism 2022, 138, 155311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawata, S.; Kozawa, J.; Yoneda, S.; Fujita, Y.; Kashiwagi-Takayama, R.; Kimura, T.; Hosokawa, Y.; Baden, M.Y.; Uno, S.; Uenaka, R.; et al. Inflammatory Cell Infiltration into Islets Without PD-L1 Expression Is Associated with the Development of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Related Type 1 Diabetes in Genetically Susceptible Patients. Diabetes 2023, 72, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Morita, S.; Kosugi, D.; Asai, Y.; Kaido, Y.; Ito, S.; Hirobata, T.; Inoue, G.; Yamamoto, Y.; Jinnin, M.; et al. Amino acid polymorphisms in human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen class II and proinsulin epitope have impacts on type 1 diabetes mellitus induced by immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1165004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Kaido, Y.; Ito, S.; Hirobata, T.; Inoue, G.; Sugita, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Jinnin, M.; Kimura, H.; Kobayashi, T.; et al. Human Leukocyte Antigens and Biomarkers in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Induced by Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 37, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.S.K.; Lee, S.; Kong, D.; Lakhani, I.; Ng, K.; Dee, E.C.; Tang, P.; Lee, Y.H.A.; Satti, D.I.; Wong, W.T.; et al. Risk of diabetes mellitus among users of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A population-based cohort study. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatouli, A.M.; Quandt, Z.; Perdigoto, A.L.; Clark, P.L.; Kluger, H.; Weiss, S.A.; Gettinger, S.; Sznol, M.; Young, A.; Rushakoff, R.; et al. Collateral Damage: Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Induced with Checkpoint Inhibitors. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, T.; Cooksley, T. Emergency Presentations of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Endocrinopathies. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 61, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, L.; Thivolet, A.; Dalle, S.; Chikh, K.; Reffet, S.; Vouillarmet, J.; Fabien, N.; Cugnet-Anceau, C.; Thivolet, C. Diabetes mellitus induced by PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: Description of pancreatic endocrine and exocrine phenotype. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 56, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Nagao, M.; Takeuchi, H.; Fukunaga, E.; Nagamine, T.; Inagaki, K.; Fukuda, I.; Iwabu, M. HLA investigation in ICI-induced T1D and isolated ACTH deficiency including meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2024, 191, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, T.P.; Araujo, D.V.; Savage, K.J.; Cheng, T.; Saha, M.; Song, X.; Gill, S.; Monzon, J.G.; Grenier, D.; Genta, S.; et al. CANDIED: A Pan-Canadian Cohort of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Cancers 2021, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, Y.; Kimura, T.; Iwamoto, H.; Sanada, J.; Fushimi, Y.; Katakura, Y.; Tatsumi, F.; Shimoda, M.; Nakanishi, S.; Mune, T.; et al. Incidence of endocrine-related immune-related adverse events in Japanese subjects with various types of cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1079074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akturk, H.K.; Michel, K.; Couts, K.; Karakus, K.E.; Robinson, W.; Michels, A. Routine Blood Glucose Monitoring Does Not Predict Onset of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Induced Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, e29–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.J.; Braunstein, R.; Flynn, J.; Zheng, J.; Lefkowitz, R.A.; Kanbour, S.; Girotra, M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Associated Diabetes: A Single-Institution Experience. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeun, R.; Iyer, P.C.; Best, C.; Lavis, V.; Varghese, J.M.; Yedururi, S.; Brady, V.; Oliva, I.C.G.; Dadu, R.; Milton, D.R.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Diabetes Mellitus at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Immunotherapy 2023, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, A.; Carroll, E.; Brooks, D.; Ben Shimol, J.; Eisenberg, E.; Wisnivesky, J.P.; Galsky, M.D.; Gallagher, E.J. Characterization of hyperglycemia in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: Beyond autoimmune insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 172, 108633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sharma, R.; Hamad, L.; Riebandt, G.; Attwood, K. Incidence of diabetes mellitus in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) therapy—A comprehensive cancer center experience. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 202, 110776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, S.; Chen, K.; Jin, P. Clinical and HLA genotype analysis of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated diabetes mellitus: A single-center case series from China. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1164120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, O.; Khalil, A.B.; Salman, B.; Atabani, A.; Al-sayegh, H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors-Induced Endocrinopathies: Assessment, Management and Monitoring in a Comprehensive Cancer Centre. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2024, 7, e00505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwal, A.; Haddox, C.; Block, M.; Kudva, Y.C. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: An emerging cause of insulin-dependent diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2019, 7, e000591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, V.H.M.; Mcgrath, R.T.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; A Scolyer, R.; Jakrot, V.; Guminski, A.D.; Long, G.V.; Menzies, A.M. Checkpoint Inhibitor–Associated Autoimmune Diabetes Is Distinct from Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 104, 5499–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Country | Aim/Design | Sample Size/Setting | Incidence/Onset | Findings | Strengths | Limitations | Study Quality Assessment | Corresponding Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stamatouli et al., 2018 United States | (PA) Identify attributes that might lead to clinical insights into ICI-DM. | N = 2960 (27 with ICI-DM) Endocrinology at Yale New Haven Hospital and University of California | (I) 0.90% (O) 20 (W) | Time of DM onset can be long after the initial CPI treatment. The presence of preexisting T2DM does not preclude the development of ICI-DM. There are clinical and laboratory features of this form of DM that are like but also clearly different from spontaneous T1DM. | Compared non-ICI-DM population with exposure group. HLA typing reveals striking information that will inform future studies. | Homogeneous population making it not very generalizable. | 91% CASP Cohort Study | [28] |

| Kotwal et al., 2019 United States | (RA) Characterize potential predictors of ICI-DM. | N = 1444 (21 with ICI-DM) Mayo Clinic, Single Institution | (I) 1.40% (O) Median 4–5 months | ICI-DM occurred most frequently with pembrolizumab (2.2%) compared with nivolumab (1%) and ipilimumab (0%). The median age was 61 years, and body mass index was 31 kg/m2, which are both higher than expected for spontaneous T1DM. The most immune related event was thyroid disease. New-onset ICI-DM developed after a median of four cycles or 5 months; 67% presented with diabetic ketoacidosis and 83% with low or undetectable C-peptide. Autoantibodies were elevated in 5/7 (71%) pts at the time of new-onset diabetes. DM did not resolve during a median follow-up of 1 year. | Large cohort sample. Generalizable to other populations. Excluded persons with preexisting T1DM and persons exposed to glucocorticoids. | Retrospective. Single institution. No pretest of the biomarkers for antibodies prior to the initiation of ICI. | 100 % CASP Cohort Study | [41] |

| Marchand et al., 2019 Europe | (PA) Describe both pancreatic functions, immunological features and change in pancreas volume in subjects ICI-DM. | N = 6 pts with ICI-DM Single institution | (I) -- (O) 4 (M) | ICI-DM was not associated with T1DM-related autoantibodies. | Immunological analysis of persons with ICI-DM along with pancreatic volume analysis. | Small sample size. Homogeneous sample. Selection bias. | 83% CASP Cohort Study | [30] |

| TsangVHM et al., 2019 Australia | (RA) Describe the nature of ICI-DM, and potential immunological and genetic predictive factors. | N = 538 pts of which 10 developed ICI-DM Melanoma Institute Australia and the Department of Endocrinology, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia | (I) 1.90% (O) 25 (W) | ICI-DM occurs within 63 weeks of starting anti-PD-1 therapy with rapid decline in C-peptide concentrations consistent with sudden b-cell failure. -Most pts do not have DAAs, and several have HLA class II haplotypes that normally protect against T1DM. CIADM is distinct from latent autoimmune diabetes of adult onset, in which positivity for DAAs is associated with slow progression of beta-cell failure. The sudden loss of C-peptide and insulin in the context of immunotherapy is a marker of CIADM. | Baseline samples of BG, hemoglobin A1c, insulin, and C-peptide were measured in plasma samples before the first dose of immunotherapy and for up to 35 months after diagnosis of ICI-DM. Large sample size. | Lack of identification of race of sample group. Only evaluated the melanoma population, which can alter some results when transcribed to other malignancies. | 85% CASP Cohort Study | [42] |

| Byun et al., 2020 United States | (RA) Characterize ICI-DM in a single-institution case series. | N = 18 pts with ICI-DM Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | (I) 0.37% (O) 3.65 (M) | Nine pts presented with DKA, and nine presented with hyperglycemia without DKA. The median initial BG was 27.92 mmol/L. There was no apparent time to IDDM differences between groups receiving combination ICI therapy versus monotherapy. Autoimmune toxicity from ICI may be associated with improved cancer-specific mortality, as an overly robust immune system could lead to increased antitumor efficacy. | Large oncology population receiving immunotherapy -Removed pt with pre-existing diabetes. Two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum testing compared pt characteristics. Overall survival was estimated using Kaplan-Meier methodology. | Lack sufficient power to detect significant subgroup differences. Small sample size. | 83% CASP Cohort Study | [35] |

| Knight et al., 2021 UK | (PA) Determine the frequency and clinical presentations of immune-mediated endocrinopathies in pts presenting as emergencies. | N = 648 pts treated with ICIs (4 with ICI-DM) Oncology Emergency Center, Single Institution | (I) 0.58% (O) 8 (C) | Presentations to emergency settings with irAE. Early recognition of immune-mediated toxicities is important. | Large population sample. Included persons with and without ICI toxicity. Findings are consistent with the current literature. | Confounding factors were not addressed such as steroids or underlying conditions like diabetes. Pancreatic enzymes needed for diagnosis ICI-DM were not mentioned. Single center evaluation. | 83% CASP Cohort Study | [29] |

| Leiter et al., 2021 United States | (RA) Characterize the prevalence and factors associated with hyperglycemia in pts treated with ICIs. | N = 385 total with 48 having new onset hyperglycemia after ICI-DM NCI-designated cancer center | (I) 0.03% (O) 9.7 (W) | New hyperglycemia in pts receiving ICIs was mostly related to glucocorticoids. A small pt subset had new unexplained hyperglycemia, suggesting that ICIs might have a role in promoting hyperglycemia. | Large sample size. Analyzed all pts treated with ICIs. Included a diverse pt population relative to clinical trials. | Retrospective. Limited analysis of A1C. No antibody testing uniformly collected on the cohort of pts who developed hyperglycemia that was not explained by other causes such as steroids. Lack of clear ICI-DM in this study. | 50% CASP Cohort Study | [37] |

| Basak et al., 2022 The Netherlands | (Nested Case-Control) Investigate C-peptide levels as a potential predictor of ICI-DM and describe the presence of islet autoantibodies and course of pancreatic enzymes in pts with and without ICI-DM. | N = 1318 pts (10 pts with ICI-DM 2 pts excluded due to primary endpoint serum data not collected before developing ICI-DM.) Erasmus University Medical Center and Amphia Hospital | (I) 0.70% (O) 6.9 (M) | -No substantial difference in C-peptide levels or course during therapy. C-peptide course before the onset of ICI-DM is not a predictive biomarker for the onset of this toxicity. Routine measurements of islet autoantibodies before or during therapy might not be useful for predicting or early detection of ICI-DM. | Matched case with controls who received the same type of treatment. | This study was not powered to perform statistical analyses. Overrepresentation of PD-1 monotherapy, which could have influenced the outcomes. Confounding factors such as steroids were not considered. | 72% CASP Case Control Studies | [22] |

| Chen et al., 2022 United States | (RA) Understand clinical risk factors for ICI-DM and its impact on survival in pts. | N = 30,337, of which 261 developed ICI-DM De-identified cohort of Optumae Clinformatics Data Mart, which captures a privately insured population from a diverse group of health plans in the U.S. | (I) 0.86% (O) 10 (W) | Dual use of immunotherapy (CTLA-4) and (PD-1) or (PD-L1) was associated with increasing risk of ICI-DM. Younger age and pre-existing non-T1DM are also associated with a higher risk of ICI-DM. Prior use of immunosuppressive medications was associated with a lower incidence of ICI-DM. The development of ICI-DM does not seem to impact pt survival significantly. | Large sample. Generalizable to the population given that they evaluated based on U.S.-wide insurance ICD codes. | Dependence on ICD-10 codes. Lack of information on severity of adverse events and tumor stage. Unable to study the effect of ICI-DM on patient survival. Unable to identify if the significance association between prior use of immunosuppressants and poor survival is because of medication or due to the underlying autoimmune disease. | 100% CASP Cohort Study | [6] |

| Inaba et al., 2022 Japan | (PA) Explain risk factors for ICI-DM. | N = 871 patients (7 patients total developed ICI-DM) Japanese Red Cross Society Wakayama Medical Center, Wakayama Medical University Hospital, and Nagoya University | (I) 0.80% (O) 2–21 (C) | HLA-DPA1*02:02 and DPB1*05:01 alleles were observed in most of the pts. Allele frequencies were significantly higher than those in ICI controls and controls of the Japanese general population. HLA-DRB1*04:05 allele frequencies were significantly higher than those in the general population. | Ability to find a linkage between HLA and the development of ICI-DM. Power analysis calculation. Able to analyze the population who did and did not develop ICI-DM. | Statistical techniques such as multiple regression analysis to identify the association of the HLA risk alleles and haplotypes with blood biomarkers could not be conducted because of the insufficient number of pts who developed ICI-DM. | 100% CASP Cohort Study | [25] |

| Muniz et al., 2022 Canada | (RA) Describe the characteristics of ICI-induced IDDM to understand their tumor response rates and survival. | N = 34 Five academic Canadian cancer centers | (I) -- (O) 2.4 (M) | In pts treated with PD-1/PD-L1, onset of ICI-DM was ~3 months. In pts treated with PD + CTLA-4, onset of ICI-DM was ~1.4 months. | Multicenter approach. ICI-induced IDDM occurs acutely and may be potentially fatal. -ICI-induced IDDM is triggered by a blockade of the PD1/PD-L1 axis. | Retrospective design. Missing demographic data (race). Lack of HLA genotyping. - Only analyzed persons with ICI-DM | 83% CASP Cohort Study | [32] |

| Chan et al., 2023 Hong Kong | (PA) Analyze risks of pts receiving PD-1 and PD-L1 agents. | N = 3375 pts were analyzed (new-onset DM occurred in 457 pts) 13.5% Data were extracted from the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System, a prospective, population-based electronic medical database. | (I) 8.6 cases per 100 person-years (O) -- | Users of ICI may have a substantial risk of new-onset DM. Risk for ICI-DM may be higher in males but did not differ between PD-1i and PD-L1i. DM occurred in 306 PD-1i users (12.6%) and 85 PD-L1 users. No difference in the risk of new-onset DM between PD-1i and PD-L1i. | Analyzed data from a population-based database that included all pts who have ever received any ICI. | Omitted pts receiving CTLA-4 inhibitors in the overall analysis. Did not specifically analyze ICI-DM. Due to the nature of the database used, cancer staging and histological subtypes were not available. Confounders not considered. | 42% CASP Cohort Studies | [27] |

| Inaba et al., 2023 Japan | (Case Control) Study novel amino acid polymorphisms in HLA class II molecules in pts with ICI-DM, to help predict the development of ICI-DM | N = 47 pts (12 who developed ICI-DM) Japanese Red Cross Society Wakayama Medical Center, Wakayama Medical University Hospital, and Nagoya University | (I) -- (O) 9–121 (W) | HLA-DP5 as a predisposition molecule was established, and significant amino acid polymorphisms at HLA-class II molecules in pts with ICI-DM. Conformational changes in the peptide-binding groove of the HLA-DP molecules may influence the immunogenicity of proinsulin epitopes in ICI-DM. | Power analysis. Detailed analysis of HLA binding. | Lack of clear matching with controls. Small sample size. | 72% CASP Case-Control Study | [25] |

| Iwamoto et al., 2023 Japan | (RA) Evaluate the incidence of endocrine-related irAEs. | N = 466 pts (5 pts with ICI-DM) Kawasaki Medical School Hospital | (I) 1.10% (O) 177.4 (D) | Endocrine-related irAEs diagnosed by blood tests were correlated with survival. Pts with a history of T2DM are more likely to develop IDDM The prevalence of anti-GAD antibodies was 51% (13), but only 1 among the 5 pts in this study. | Analysis of multiple endocrine irAE. Large sample size. | Single-center, retrospective, observational study. Homogenous population. Endocrine testing was not performed in all pts. | 66% CASP cohort study | [33] |

| Jeun et al., 2023 United States | (RA) Characterize clinical outcomes and survival in melanoma pts with ICI-DM. | N = 76 pts with ICI-DM The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center | (I) -- (O) 12.5 (W) | Pts who had ICI-DM were younger, and a higher percentage were undergoing combination therapy with anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1 agents than pts in the control group. | Single largest cohort of pts with ICI-DM. Provided novel information on the use of diabetes technology in this pt population and highlighted the risk of readmissions and BG variability in these pts. | Retrospective. Limited to survival comparison in the melanoma cohort due to lack of access to clinical databases for other cancer subtypes. | 91% CASP Cohort Study | [36] |

| Kawata et al., 2023 Japan | (Case Control) Evaluate pancreatic histological findings of ICI-DM compared with those of pts who received ICI therapy but did not develop ICI-DM. | N = 11 3 ICI pts, 3 non-T1DM pts, and seven controls. Osaka University | (I) -- (O)12 (W) | Confirmed the depletion of beta cell area, the increase of alpha-cell area, and the infiltration of macrophages as well as T lymphocytes to and around the islets in the ICI-DM pts. Absence of PD-L1 expression on residual beta and alpha cells in these pts. | Power analysis. Evaluation of HLA typing in pancreatic tissue. | Small sample size. Study included surgical cases and autopsy cases. Pancreatic tissues of autopsy cases may be less stained than those of surgical cases; the results should be interpreted with caution. No analysis of monoclonality of T-lymphocytes infiltrating into the pancreas in both ICI-DM pts and non-T1DM pts. | 28% CASP Case Control Study | [24] |

| Lee et al., 2023 Korea | (Case Control) Compare the risk of new-onset DM between pts receiving an ICI and those receiving CC. | N = 1326 total, but 221 received ICI therapy of whom 27 pts developed ICI-DM) Tertiary care hospital database at Severance Hospital | (I) 0.12% (O) 17–56 (C) | ICI therapy is associated with an increased risk of incident diabetes compared with CC. The BG levels of pts treated with an ICI, especially males and those with prominent lymphocytosis after ICI treatment, need to be monitored regularly to detect ICI-DM as early as possible. | Case control matched age, sex, and cancer type to the ICI group. All pts receiving steroids were excluded. Trajectory approach was performed with a collection of demographic and laboratory data, allowing investigation on whether the trajectory cluster with an increasing BG pattern in the ICI group had distinguishable clinical characteristics. | Retrospective analysis. Trajectory changes in insulin resistance and secretion were not investigated. No reporting of how the diagnosis of ICI-DM is concluded and confirmed. | 81% CASP Case Control Study | [23] |

| Liu et al., 2023 China | (Cohort Study) Investigate the clinical characteristics and HLA genotypes of pts with ICI-DM | N = 74 pts with (23 having ICI-DM) Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University | (I) -- (O) 5 (C) | ICI-DM shares similar clinical features with T1DM, such as acute onset, poor islet function, and insulin dependence. Marked differences in T1DM, the lack of islet autoantibodies. Low frequencies of HLA typing T1DM susceptibility and high frequencies of protective HLA haplotypes. | Strong comparison of T1DM with persons with ICI-DM. Clean data collection with antibodies collected on 98% of pts. Statistical and clinical significant information. | Small sample size. Single institution. Homogeneous population. | 91% CASP Cohort Study | [39] |

| Zhang et al., 2023 United States | (RA) Report the incidence and characteristics of new onset and worsening of DM in pts treated with ICIs. | N = 2477 (25 with ICI-DM) Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Institution | (I) 1.01% (O) 12 (W) | The incidence of ICI-DM or worsening of DM is 1.01%. ICI-DM is usually associated with the use of PD-1 or PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors and not anti- CTLA-4 therapy. Among the 14 pts who developed new onset ICI-DM, 93% received a PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor and 7% received a PD-L1. 3 pts received CTLA-4 as a combination therapy. | Large cohort over 10 years of data. Appropriate exclusion of pts on glucocorticoids. | Retrospective. Lack of comparison of incidence of DM in a cohort of oncological pts treated vs. not treated with ICIs. Not all pts assessed for pancreatic antibodies, which would have helped inform the current body of literature on ICI-DM. | 100 % CASP Cohort Study | [38] |

| Akturk et al., 2024 United States | (RA) Investigate whether routine monitoring of BG can predict the onset of hyperglycemia associated with ICI-DM. | N = 89 adults (13 with ICI-DM) Single center | (I) 0.15% (O) 3 (M) | Greater than 70% of pts develop ICI-DM in the first 90 days after the first dose. Routine monitoring of BG at ICI infusion visits does not predict the rapid onset of hyperglycemia associated with ICI-DM but could be beneficial for pts at high risk, such as those having HLA-DR4. | Large longitudinal data set of BG with a comparison of two groups (ICI-DM and ICI with no T1DM). There is a need to monitor BG levels more vigilantly. | Retrospective. Variable exposure to glucocorticoids not identified. | 91% CASP Cohort Study Checklist | [33] |

| Elshafie et al., 2024 Oman | (RA) Determine characteristics and management of ICI-related endocrinopathies. | N = 139 pts (1 pt developed ICI-DM) Sultan Qaboos Comprehensive Cancer Care and Research Centre | (I) 0.70% (O) 3 months | Pts diagnosed with genitourinary cancers had a significantly higher risk of developing endocrine irAEs. The presence of any comorbidity versus no comorbidity was a significant negative predictor of toxicity. A higher disease stage (namely, stage IV) did not predict toxicity. Prior history of treatment, including surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, was not associated with toxicity. | Focused oncology center population. Ability to review multiple irAE related to endocrine. -Study of the entire oncology population instead of focusing only on the group that developed adverse events. | Retrospective. Absence of standardized testing protocol for assessing endocrine adverse effects. Single center. Small sample size. | 87% CASP Cohort Studies | [40] |

| Ono et al., 2024 Japan | (PA) Analyze and compare HLA signatures associated with ICI-DM and ICI-IAD in pts with both conditions. | N = 47 (33 with ICI-DM) Single Center | (I) -- (O) 22–29 (W) | DQA1*03:02, and DRB1*13:02-DQB1*06:04 were considered susceptible HLAs DRB1*15:02-DQB1*06:01 was considered a protective HLA. In pts with ICI-IAD, DRB1*15:02-DQB1*06:01, is considered a susceptible HLA. Given that DRB1*15:02-DQB1*06:01 was not detected in pts with ICI-DM/IAD, the presence of the DRB1*15:02-DQB1*06:01 haplotype appeared to protect against the co-occurrence of T1DM in pts with ICI-IAD. | Power analysis. HLA analysis in the ICI-DM group, along with complete pancreatic analysis from the entire sample. | -Small sample size. Missing data from some HLA analysis. Homogeneous sample. Lack of comparative assessment with persons without ICI-DM who are exposed to immunotherapy. | 83% CASP Cohort Study | [31] |

| Ruiz-Esteves et al., 2024 United States | (RA) Define incidence, risk factors, and clinical spectrum of ICI-DM. | N= 14,328 (64 with ICI-DM) Mass General Brigham | (I) 0.45% (O) NR | Preexisting T2DM and treatment with combination ICI were risk factors of ICI-DM. T1DM was associated with ICI-DM risk, demonstrating a genetic association between spontaneous autoimmunity and irAEs. Pts with ICI-DM were in 3 distinct phenotypic categories based on autoantibodies and residual pancreatic function, with varying severity of initial presentation. | Large cohort with heterogeneous population. Multiple malignancies represented. Compared persons with and without ICI-DM. | Retrospective. Not able to determine how combination chemotherapy/ICI regimens may be associated with the incidence of ICI-DM. Genetic data reflect pts who were included in the PROFILE study and not the full cohort, posing selection bias. | 91% CASP Cohort Study | [13] |

| Citation | Age/Race/Gender/PMH-DM Host Characteristics | Underlying Malignancy Host Characteristics | Agent Characteristics | HLA Expression and T-Cell Upregulation Microenvironment | Pancreatic Auto antibodies Microenvironment | C-Peptide Microenvironment | Corresponding Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stamatouli et al., 2018 | ◦Age: 66 years ◦Race: 24 Whites, 1 Asian, 1 Hispanic, 1 Non-Hispanic ◦Gender: 17 males, 10 females PMH-DM: 4 with pre-DM and 2 with T2DM | ◦14 Melanoma ◦3 RCC ◦4 NSCLC ◦1 SCLC ◦1 CholangioCA ◦1 Neuroendocrine tumor ◦1 Pancreatic CA ◦1 GI CA ◦1 SCC | PD-1 ◦14 PD-L1 ◦1 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦12 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: None of the subjects expressed the T1DM protective allele HLA-DR2. There was a predominance of HLA-DR4 (16/21, 76%) T-Cell Upregulation -- | GAD+ (9 pts), Anti IA2 (5 pts), Anti ZnT8 (2 pts), Islet cell antibodies (2 pts) | 23 low or undetectable C-peptide | [28] |

| Kotwal et al., 2019 | ◦Age: 61.3 years ◦Race: 20 Whites, 1 Black ◦Gender: 12 males, 9 females PMH-DM: 11 (pre-DM or prior T2DM) | ◦9 Melanoma ◦5 Lung CA ◦2 Breast CA ◦1 RCC ◦1 MM ◦1 Lymphoma ◦1 Merkel Cell CA ◦1 Esophageal CA ◦1 Pancreatic CA | PD-1 ◦21 (17 with Pembro and 4 with Nivo) PD-L1 ◦None CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦None Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | -- | GAD+ (10/14 pts), IA-2+ (2/12 pts), ZnT8 (0/8), | Low in 10/14 pts | [41] |

| Marchand et al., 2019 | ◦Age: 67 years ◦Race: 100% White ◦Gender: 5 males, 1 female PMH-DM: None | ◦(3) Melanoma ◦(1) Lung CA ◦(1) Pleiomorphic pulmonary CA ◦(1) Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | PD-1 ◦4 PD-L1 ◦1 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦1 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: None with HLA Class II profiles (high-risk T1DM) (2) with HLA Class II haplotypes that confer protection against T1DM. T-Cell Upregulation -- | GAD neg, IA-2A+ (1 pt), ZnT8 neg, | 4 with undetectable C-peptide and 2 with detectable levels | [30] |

| TsangVHM et al., 2019 | ◦Age: 62 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 9 males, 1 female PMH-DM: 1 | Melanoma | PD-1 ◦6 PD-L1 ◦None CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦4 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: 3 patients with risk haplotype for T1DM and 3 with HLA haplotype associated with protection against T1DM. T-Cell Upregulation -- | Negative for islet antigen, insulin antibody, zinc transporter. | All with low C-peptide | [42] |

| Byun et al., 2020 | ◦Age: 63.5 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 10 males, 8 females PMH-DM: None | The most common primary cancer was melanoma | PD-1 ◦12 PD-L1 ◦5 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI-Medication ◦Nine patients received CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and one who received PD-1 and PD-L1 at different time points. Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: HLA class I T-Cell Upregulation -- | Five of the 12 patients were positive for GAD65 autoantibodies. | Of the 18 patients, 11 trended toward or had undetectable C-peptide levels. | [35] |

| Knight et al., 2021 | ◦ Age: 72 years ◦ Race: NR ◦Gender: 100% males PMH-DM: NR | ◦2 with melanoma ◦1 RCC ◦1 Prostate CA | PD-1 ◦4 PD-L1 ◦None CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦None Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | -- | -- | -- | [29] |

| Leiter 2021et al., | ◦Age: 63.9 years ◦Race: 16 Whites, 4 Blacks, 9 Hispanics, 8 Asians, 11 Unknown ◦Gender: 33 males PMH-DM: 19 | ◦(12) NSCLC ◦(13) HCC ◦(12) RCC ◦(17) SCC of HandN ◦(6) Melanoma ◦(4) Urothelial Cell CA ◦(4) MM ◦(3) Other | PD-1/PD-L1 ◦34 (study grouped this category with PD-1 and PD-L1) CTLA-4 ◦6 Combo ICI and Medication ◦None Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | -- | GAD+ in one patient | C-peptide low in one patient | [37] |

| Basak et al., 2022 | ◦Age: 69.5 years ◦Race: White 100% ◦Gender: 62.5% males, 37.5% females PMH DM: None | ◦Melanoma and NSCLC (37.5% each). ◦RCC 12.5% ◦Urothelial Cell CA 12.5% | PD-1 ◦Nivolumab monotherapy (62.5%) ◦Pembrolizumab monotherapy (25%) PD-L1 ◦None CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦12.5% Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | -- | Two patients (25%) in the ICI-related diabetes group had positive islet autoantibodies before the onset of ICI-DM, one at baseline and one in the last sample before the onset of ICI-related diabetes, whereas one patient (6%) in the control group had positive islet autoantibodies at baseline. After the onset of ICI-DM, four patients (50%) (of whom two were already seropositive before diabetes onset) had positive islet autoantibodies. | At baseline, the median C-peptide concentration in cases was 1.73. Two out of five patients in whom C-peptide was measured during routine clinical care had C-peptide concentrations below the reference range at diagnosis of diabetes, of whom both had diabetic ketoacidosis. The only other patient with diabetic ketoacidosis had a C-peptide level in the reference range at diagnosis. | [22] |

| Inaba et al., 2022 | ◦Age: 72.2 years ◦Race: 100% Asian ◦Gender: 6 males, 1 female PMH-DM: 1 | ◦4 NSCLC ◦1 metastatic melanoma in | PD-1 ◦6 PD-L1 ◦1 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦ 1 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: HLA-DRB1*04:05 allele frequencies were significantly higher in ICI-T1DM patients than in controls. Notably, the frequencies of HLA-DPA1*02:02 and its associated allele, DPB1*05:01, were significantly associated with an increased risk of ICI-T1DM compared to the controls. T-Cell Upregulation -- | Pancreatic beta-cell autoantibodies were all negative except for 1 patient. | Undetectable in all patients 1 month after diagnosis | [26] |

| Muniz et al., 2022 | ◦Age: 60.5 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 25 males, 9 females PMH-DM: 7 with either pre-DM or NIDDM | ◦19 Melanoma ◦4 with RCC ◦4 with NSCLC ◦7 other | PD-1/PD-L1 ◦20 but combined with PD-1 and PD-L1 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦None Combo ICI and Chemo ◦5 | -- | GAD (measured in 11 pts; + in 5 pts), insulin antibodies (measured in 1 patient; neg); anti-islet cell, negative; zinc transporter, negative | Measured in 17 pts (7 with undetectable values and the another 6 although detectable was low, and 4 with normal levels. | [32] |

| Chan et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 62.2 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 3375 Total, 65.2% males 326 males developed ICI-DM and 131 females developed ICI-DM PMH-DM: None | Almost half of the patients had lung CA | PD-1 ◦2749 PD-L1 ◦691 CTLA-4 ◦369 Combo ICI and Medication ◦NR Combo ICI and Chemo ◦2038 | -- | -- | -- | [27] |

| Inaba et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 75 years ◦Race: Asian 100% ◦Gender: 9 males, 3 females PMH-DM: None | ◦7 NSCLC ◦3 MM ◦1 RCC ◦1 SCLC | PD-1 ◦10 PD-L1 ◦1 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦1 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: HLA-DPB1*05:01 allele frequency was more significantly associated with an increased risk of ICI-T1DM compared with general controls. T-Cell Upregulation -- | -- | -- | [25] |

| Iwamoto et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 69 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 68% males, 32% females PMH-DM: 3 | Solid tumors were mentioned, but the ones associated with the development of ICI-DM were not clearly identified. | PD-1 ◦351 (1.4% with ICI-DM) PD-L1 90 (none developed ICI-DM) CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦25 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | -- | GAD+ in 1 patient | -- | [33] |

| Jeun et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 60 years ◦Race: 63 Whites, 5 Hispanics, 4 Asians, 4 Blacks ◦Gender: 43 males PMH-DM: 12 | ◦23 MM ◦12 lung CA ◦11 with RCC; Others with GBM, prostate, angiosarcoma, cancer of unknown primary, HCC, parotid CA, ovarian CA, ATC, esophageal CA, and serous adeno CA | PD-1 ◦54 PD-L1 ◦11 CTLA-4 ◦1 Combo ICI and Medication ◦10 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦37% tyrosine kinase or VEGF inhibitors, or other agents intended to enhance the antitumor immune response by targeting CD137, CXCR4, IDO1, CSF1R, STAT3, or CCR4 | -- | GAD 65+ (40/69 pts) IA2+ (7/58 pts) Anti Insulin+ (11/58 pts) ZnT8+ (2/20 pts) | Median C-peptide at 4 weeks 0.2 ng/mL f/b 0 ng.ml | [36] |

| Kawata et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 64 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 100% males PMH-DM: NR | Urothelial CA Hodgkin lymphoma RCC | PD-1 ◦2 PD-L1 ◦None CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦1 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: DRAB1-DQB1+ (2 pts) T-Cell Upregulation -- | GAD+ (2 pts) IA2+ (1 pt) | <0.02–0.6 | [24] |

| Lee et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 60.4 years ◦Race: 100% Asian ◦Gender: 136 males PMH-DM: None | Lung, liver, breast | PD-1 ◦154 PD-L1 ◦67 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦None Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | -- | -- | -- | [23] |

| Liu et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 57.2 years ◦Race: Asian 100% ◦Gender: 17 males, 5 females PMH-DM: None | ◦43.5% lung cancer ◦8.7% tongue carcinoma ◦8.7% had gastric carcinoma; the remaining were affected by different types of carcinomas | PD-1 ◦18 PD-L1 ◦4 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦1 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: 13 with HLA haplotype, 22.7% had both susceptible and protective haplotypes, and 31.8% carried only protective HLA haplotypes T-Cell Upregulation -- | IAA Negative, IA-2 Negative, ZnT8 Negative, GAD+ (2 pts) | 23 patients with low C-peptide | [39] |

| Zhang et al., 2023 | ◦Age: 65 years ◦Race: 22 Whites, 3 Blacks ◦Gender: 14 males, 11 females PMH-DM: 11 | ◦8 Melanoma ◦7 Lung CA ◦5 RCC ◦2 Bladder CA ◦1 Anal CA ◦1 Head and Neck CA ◦1 Prostate CA | PD-1 ◦16 PD-L1 ◦2 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦3 and an additional 4 with sequential ICI therapy Combo ICI and Chemo ◦ None | -- | GAD+ in 2/11, ZnT8 (0/11), IAA (1/6) | 5/11 with low C-peptide | [38] |

| Akturk et al., 2024 | ◦Age: 53.2 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 62 males, 27 females PMH-DM: None | Advanced melanoma (stage III unresectable and stage IV) | PD-1 ◦Did not clearly quantify, but mentioned that 50% developed ICI-DM after anti-PD-1 PD-L1 ◦None CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦Did not clearly quantify, but mentioned 50% developed ICI-DM after combo PD-1/PD-L1 + CTLA4 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: (70%) ICI-T1D patients had HLA-DR4 T-Cell Upregulation -- | 1 (14%) GAD+ pre-treatment and 4 GAD + post treatment | 3 with C-peptide levels very low or absent | [34] |

| Elshafie et al., 2024 | ◦Age: 56 years ◦Race: NR ◦Gender: 59 males, 80 females PMH-DM: None | ◦33 Breast ◦31 Lung ◦17 gastric | PD-1 ◦120 PD-L1 ◦19 CTLA-4 ◦Not reported Combo ICI and Medication ◦NR Combo ICI and Chemo ◦NR | -- | 1 patient GAD positive 3 months after diagnosis. | 1 patient with low C-peptide 3 months after diagnosis | [40] |

| Ono et al., 2024 | ◦Age: 64.7 years ◦Race: 100% Asian ◦Gender: 21 males, 12 females PMH-DM: NR | ◦10 NSCLC ◦4 RCC ◦2 Melanoma ◦2 Ureteral ◦2 Breast ◦1 Pancreatic ◦1 Oropharyngeal ◦1 Colon ◦1 Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma | PD-1 ◦22 PD-L1 ◦5 CTLA-4 ◦None Combo ICI and Medication ◦6 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | HLA: DRB1*09:01 − DQB1*03:03 = 27.3% DRB1*13:02 − DQB1*06:04 = 13.6% DRB1*15:02 − DQB1*06:01 = 0% T-Cell Upregulation -- | (9 +) with islet autoantibodies and (7) GAD+; IA-2 (2 positive), 11 tested for ZnT8 (all negative) | -- | [31] |

| Ruiz-Esteves et al., 2024 | ◦Age: 64 years ◦Race: 60 Whites, 3 Asians, 1 Black ◦Gender: 32 males, 32 females PMH DM: 16 | ◦23 Melanoma ◦15 Thoracic CA ◦9 GU CA ◦5 Breast CA ◦3 GI, H&N, Neuro CA ◦2 Hematological CA ◦1 CA of Unknown Primary | PD-1 ◦43 PD-L1 ◦4 CTLA-4 ◦2 Combo ICI and Medication ◦15 Combo ICI and Chemo ◦None | -- | 1 antibody (the study did not identify which antibodies) | 38 with low C-peptide | [13] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crowder, V.; Brady, V. Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Diabetes Mellitus: An Integrative Review. Life 2025, 15, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071063

Crowder V, Brady V. Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Diabetes Mellitus: An Integrative Review. Life. 2025; 15(7):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071063

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrowder, Vivian, and Veronica Brady. 2025. "Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Diabetes Mellitus: An Integrative Review" Life 15, no. 7: 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071063

APA StyleCrowder, V., & Brady, V. (2025). Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Diabetes Mellitus: An Integrative Review. Life, 15(7), 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071063