Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a New Section and Two New Species of Alternaria from Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Isolates

2.2. Morphological Characterization

2.3. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

2.4. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results

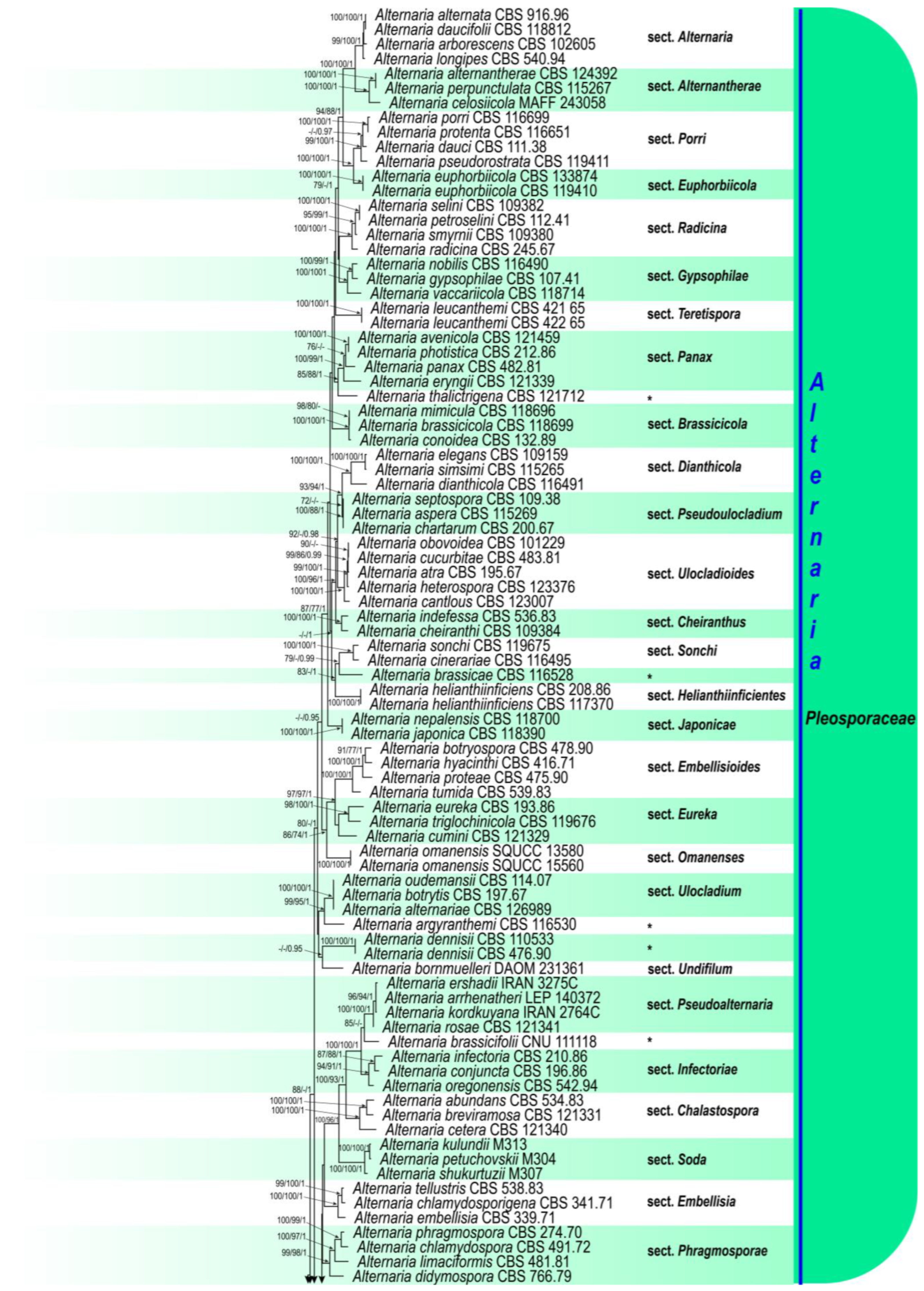

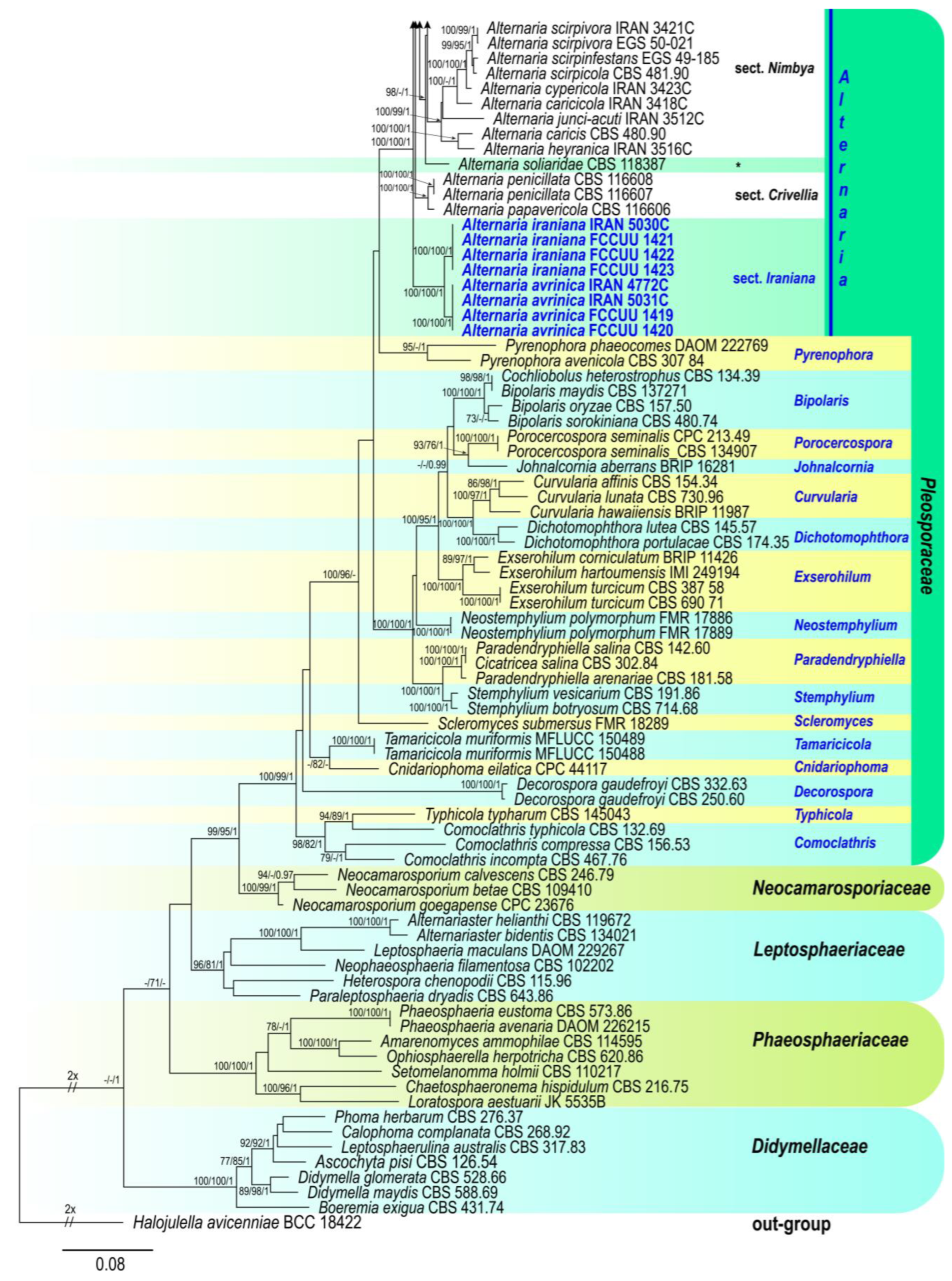

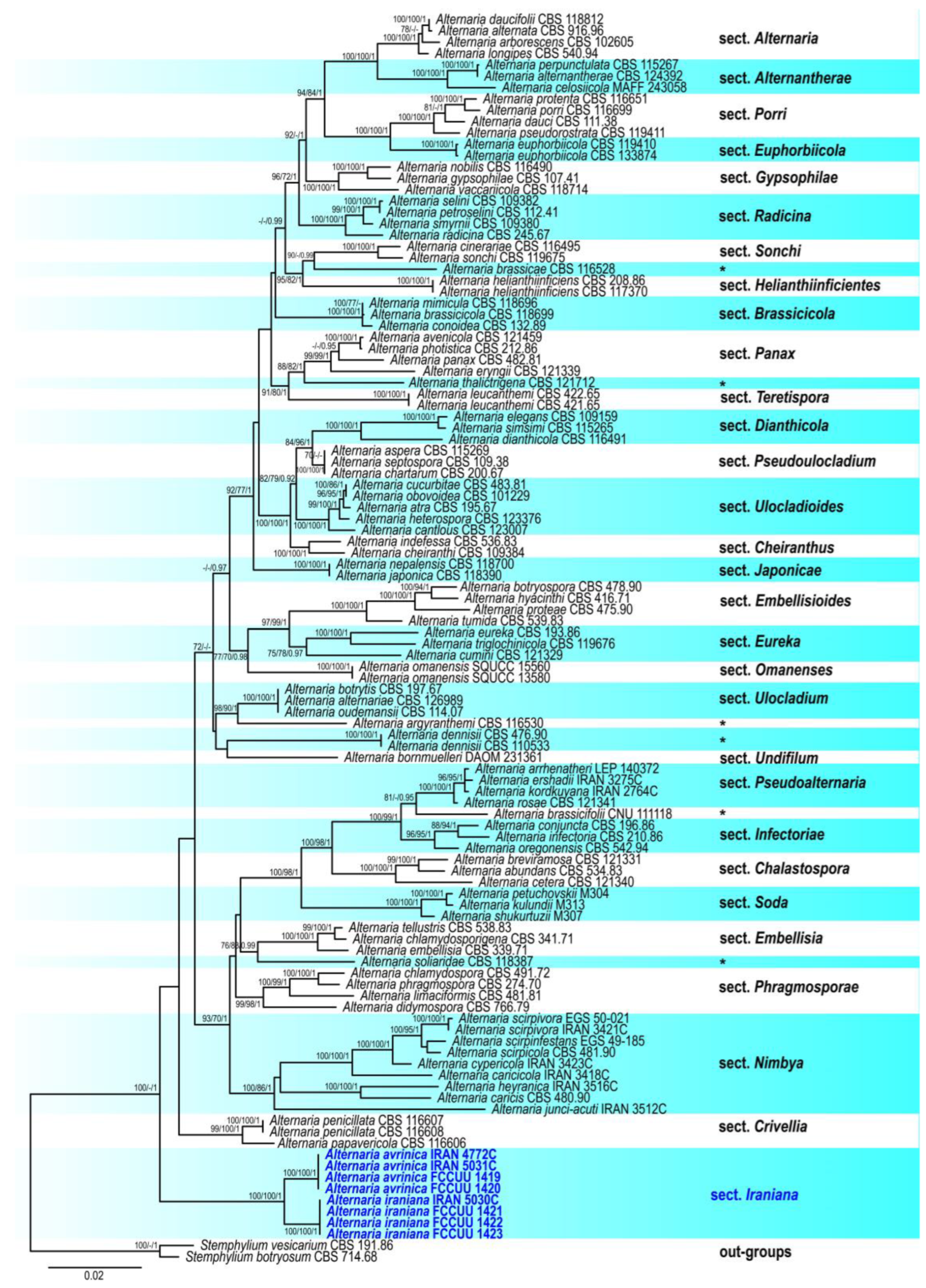

3.1. Phylogenetic Analyses

3.2. Taxonomy

3.2.1. Section Iraniana A. Ahmadpour, Y. Ghosta, Z. Alavi, F. Alavi & L. Mohammadi, sect. nov.

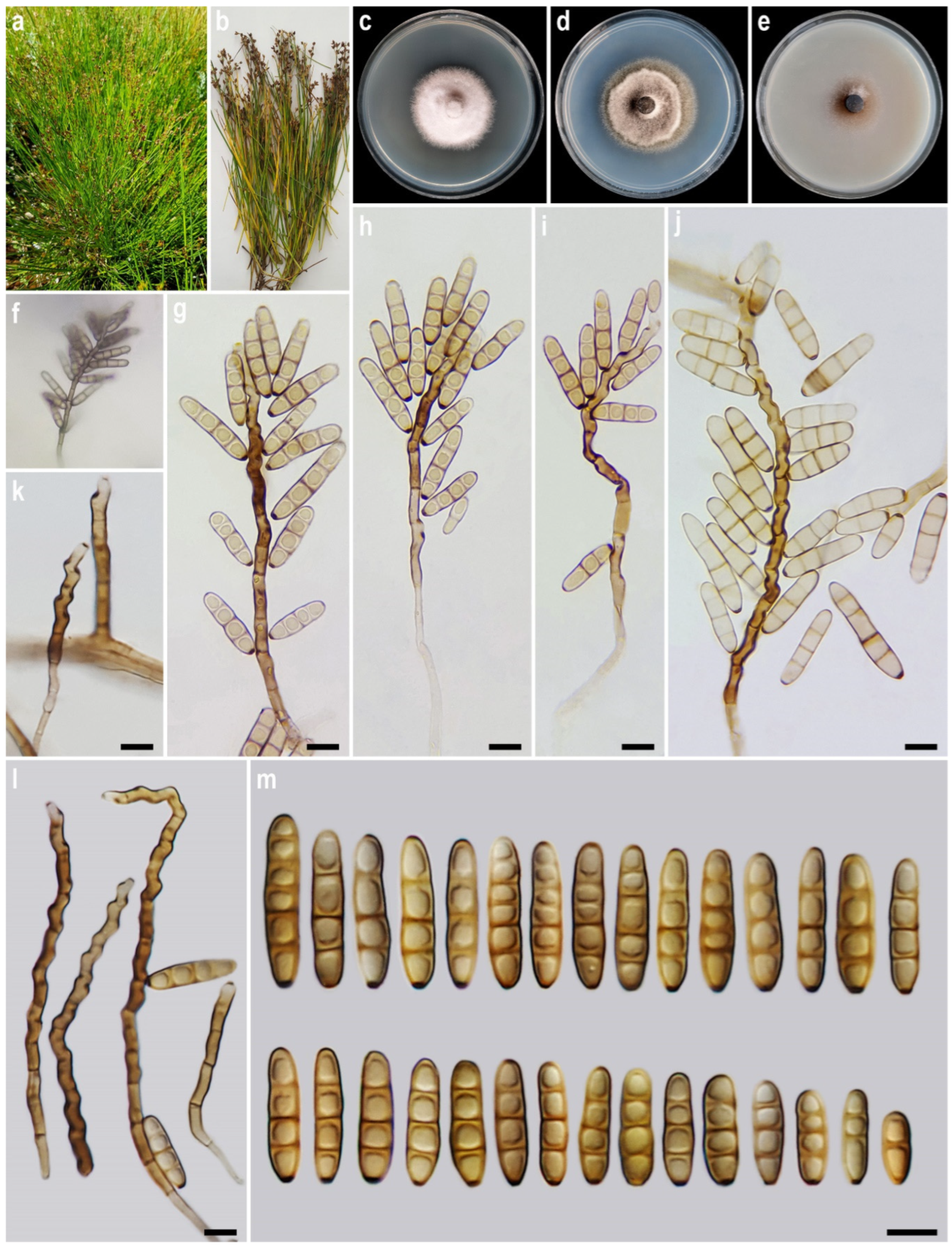

3.2.2. Alternaria avrinica A. Ahmadpour, Y. Ghosta, Z. Alavi, F. Alavi & L. Mohammadi, sp. nov. (Figure 3)

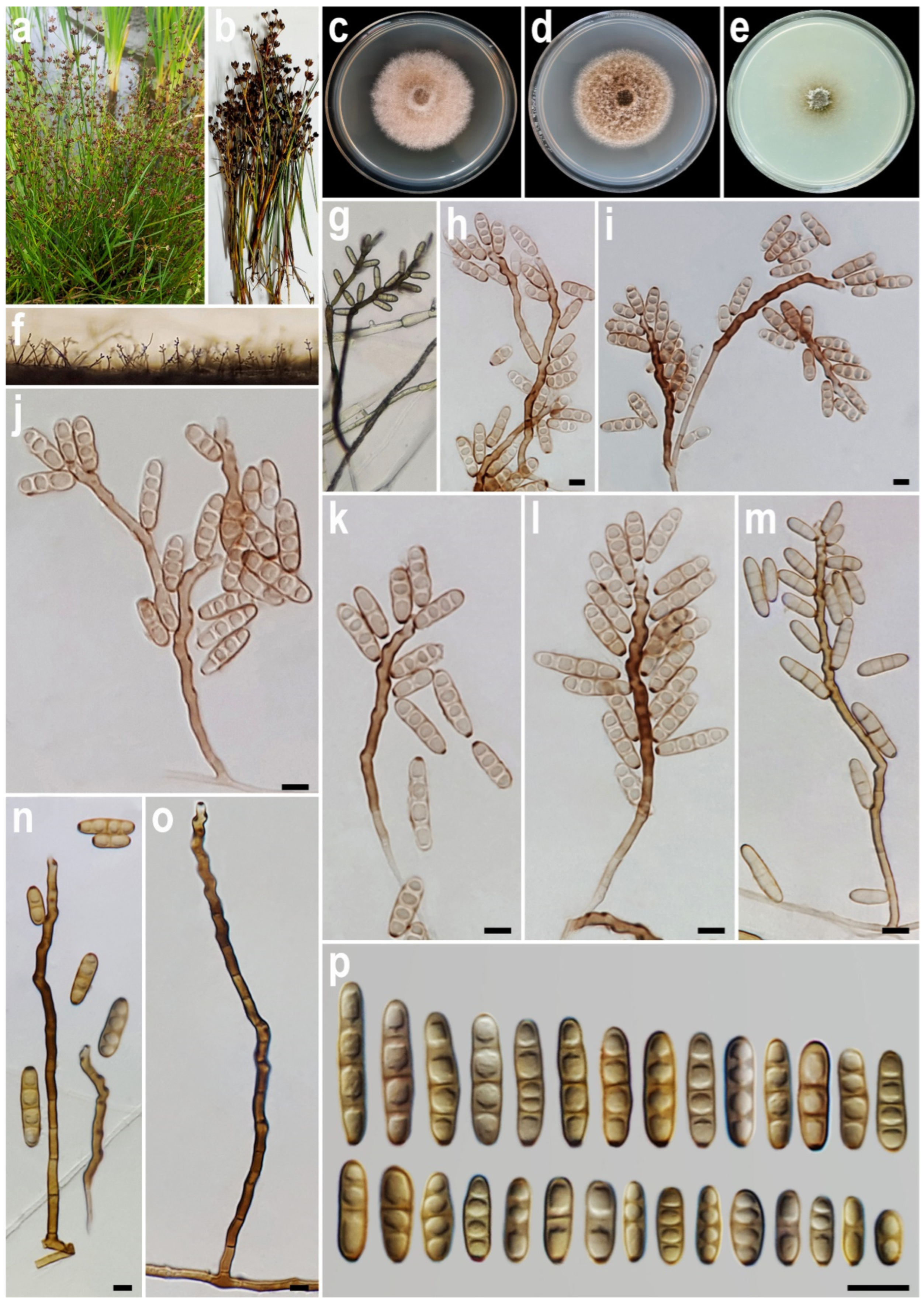

3.2.3. Alternaria iraniana A. Ahmadpour, Y. Ghosta, Z. Alavi, F. Alavi & L. Mohammadi, sp. nov. (Figure 4)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nees von Esenbeck, C.G. Das System der Pilze und Schwämme: Ein Versuch; Stahel: Würzburg, Germany, 1816. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J.A. Taxonomic characters of the genera Alternaria and Macrosporium. Am. J. Bot. 1917, 4, 439–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, E.G. Typification of Alternaria, Stemphylium, and Ulocladium. Mycologia 1967, 59, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, S.P. The foundation species of Alternaria and Macrosporium. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1933, 18, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, E.M. Systema Mycologicum. Vol. 3; Gryphiswaldae: Sumtibus Ernesti Maurittii: Gryphiswaldia, Germany, 1832. [Google Scholar]

- Thomma, B.P. Alternaria spp.: From general saprophyte to specific parasite. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2003, 4, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.P.; Gannibal, P.B.; Peever, T.L.; Pryor, B.M. The sections of Alternaria: Formalizing species-group concepts. Mycologia 2013, 105, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudenberg, J.; Groenewald, J.; Binder, M.; Crous, P. Alternaria redefined. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 75, 171–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Keissler, K. Zur kenntnis der pilzflora krains. Beih. Bot. Centralbl. 1912, 29, 395–440. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, P. Danish Species of Alternaria and Stemphylium; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Joly, P. Le Genre Alternaria. Encyclopédie Mycologique XXXIII; P. Lechevalier: Paris, France, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, M.B. Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes; Commonwealth Mycological Institute: Kew, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, M.B. More Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes; Commonwealth Mycological Institute: Kew, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria themes and variations (1–6). Mycotaxon 1981, 13, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria themes and variations (11–13). Mycotaxon 1982, 14, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria themes and variations (14–16). Mycotaxon 1986, 25, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria themes and variations (17–21). Mycotaxon 1986, 25, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria themes and variations (22–26). Mycotaxon 1986, 25, 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria themes and variations (27–53). Mycotaxon 1990, 37, 79–119. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria taxonomy: Current status, viewpoint, challenge. In Alternaria Biology, Plant Diseases and Metabolites; Chelkowski, J., Visconti, A., Eds.; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria themes and variations (112–144). Mycotaxon 1995, 55, 55–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.G.; Cramer, R.A.; Lawrence, C.B.; Pryor, B.M. Alt a 1 allergen homologs from Alternaria and related taxa: Analysis of phylogenetic content and secondary structure. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.P.; Park, M.S.; Pryor, B.M. Nimbya and Embellisia revisited, with nov. comb. for Alternaria celosiae and A. perpunctulata. Mycol. Prog. 2012, 11, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, B.M.; Gilbertson, R.L. Molecular phylogenetic relationships amongst Alternaria species and related fungi based upon analysis of nuclear ITS and mt SSU rDNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 2000, 104, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, B.M.; Bigelow, D.M. Molecular characterization of Embellisia and Nimbya species and their relationship to Alternaria, Ulocladium and Stemphylium. Mycologia 2003, 95, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, M.; Peever, T.L.; Pryor, B.M. An expanded multilocus phylogeny does not resolve species among the small-spored Alternaria species complex. Mycologia 2009, 101, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Geng, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.G. Sinomyces: A new genus of anamorphic Pleosporaceae. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Truter, M.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Large-spored Alternaria pathogens in section Porri disentangled. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 79, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grum-Grzhimaylo, A.A.; Georgieva, M.L.; Bondarenko, S.A.; Debeta, A.J.M.; Bilanenko, E.N. On the diversity of fungi from soda soils. Fungal Divers. 2016, 76, 27–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.P.; Rotondo, F.; Gannibal, P.B. Biodiversity and taxonomy of the pleomorphic genus Alternaria. Mycol. Prog. 2016, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafri, A.A.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Al-Saady, N.A.; Al-Sadi, A.M. A new section and a new species of Alternaria encountered from Oman. Phytotaxa 2019, 405, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannibal, P.B.; Orina, A.S.; Gasich, E.L. A new section for Alternaria helianthiinficiens found on sunflower and new asteraceous hosts in Russia. Mycol. Prog. 2022, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, A.; Ghosta, Y.; Poursafar, A. Novel species of Alternaria section Nimbya from Iran as revealed by morphological and molecular data. Mycologia 2021, 113, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, E.G. Macrospora Fuckel (Pleosporales) and related anamorphs. Sydowia 1989, 41, 314–329. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, E.G. Alternaria an Identification Manual; CBS Fungal Biodiversity Centre: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, R.W. A Mycological Colour Chart; Commonwealth Mycological Institute: Kew, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W.; Gams, W.; Stalpers, J.A.; Robert, V.; Stegehuis, G. MycoBank: An online initiative to launch mycology into the 21st century. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadpour, A. Alternaria caricicola, a new species of Alternaria in the section Nimbya from Iran. Phytotaxa 2019, 405, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, A.; Ghosta, Y.; Alavi, Z.; Alavi, F.; Poursafar, A.; Rampelotto, P.H. Diversity of Alternaria section Nimbya in Iran, with the description of eight new species. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Shinsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Berbee, M.L.; Pirseyedi, M.; Hubbard, S. Cochliobolus phylogenetics and the origin of known, highly virulent pathogens, inferred from ITS and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene sequences. Mycologia 1999, 91, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, G.H.; Sung, J.M.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Spatafora, J.W. A multi-gene phylogeny of Clavicipitaceae (Ascomycota, Fungi): Identification of localized incongruence using a combinational bootstrap approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 44, 1204–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Seidl, M.F.; Groenewald, J.Z.; de Vries, M.; Stielow, J.B.; Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Crous, P.W. Alternaria section Alternaria: Species, formae speciales or pathotypes. Stud. Mycol. 2015, 82, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, J.; Nakashima, C. Japanese species of Alternaria and their species boundaries based on host range. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2020, 5, 197–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 108, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, W.P.; Maddison, D.R. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis. Version 3.61. 2019. Available online: http://www.mesquiteproject.org (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylander, J.A.A. MrModeltest v2.0. Program Distributed by the Author; Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. The CIPRES Science Gateway: Enabling High-Impact Science for Phylogenetics Researchers with Limited Resources. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment: Bridging from the Extreme to the Campus and Beyond (ACM), Chicago, IL, USA, 16–20 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Swofford, D.L. Paup: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (and Other Methods) 4.0. B5. Version 4.0b10; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree, a Graphical Viewer of Phylogenetic Trees. 2019. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Inderbitzin, P.; Shoemaker, R.A.; O’Neill, N.R.; Turgeon, B.G.; Berbee, M.L. Systematics and mating systems of two fungal pathogens of opium poppy: The heterothallic Crivellia papaveracea with a Brachycladium penicillatum asexual state and a homothallic species with a Brachycladium papaveris asexual state. Can. J. Bot. 2006, 84, 1304–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatulli, M.T.; Fanelli, F.; Moretti, A.; Mule, G.; Logrieco, A.F. Alternaria species and mycotoxins associated to black point of cereals. Mycotoxins 2013, 63, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somma, S.; Amatulli, M.T.; Masiello, M.; Moretti, A.; Logrieco, A.F. Alternaria species associated to wheat black point identified through a multilocus sequence approach. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 293, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, H.; Jeewon, R.; Hongsanan, S.; Bhat, D.J.; Tang, S.M.; Lumyong, S.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.C.; Camporesi, E.; et al. Alternaria: Update on species limits, evolution, multi-locus phylogeny, and classification. Stud. Fungi 2023, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, L.; Htun, A.A.; Yu, Z.H.; Deng, J.X.; Li, Q.L. Morphological and molecular identification of two new Alternaria species (Ascomycota, Pleosporaceae) in section Radicina from China. MycoKeys 2021, 78, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Li, D.W.; Cui, W.L.; Huang, L. Seven new species of Alternaria (Pleosporales, Pleosporaceae) associated with Chinese fir, based on morphological and molecular evidence. MycoKeys 2024, 101, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Phookamsak, R.; Jiang, H.; Bhat, D.J.; Camporesi, E.; Lumyong, S.; Kumla, J.; Hongsanan, S.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.; et al. Additions to the inventory of the genus Alternaria section Alternaria (Pleosporaceae, Pleosporales) in Italy. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.H.; Gou, Y.N.; New, Z.M.; Aung, S.L.L.; Deng, J.X.; Li, M.J. Alternaria youyangensis sp. nov. (Ascomycota: Pleosporaceae) from leaf spot of Fagopyrum esculentum in China. Phytotaxa 2024, 672, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwe, Z.M.; Htut, K.N.; Aung, S.L.L.; Gou, Y.N.; Huang, C.X.; Deng, J.X. Two novel species and new host of Alternaria (Pleosporales, Pleosporaceae) from sunflower (Compositae) in Myanmar. MycoKeys 2024, 105, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessadat, N.; Bataillé-Simoneau, N.; Colou, J.; Hamon, B.; Mabrouk, K.; Simoneau, P. New members of Alternaria (Pleosporales, Pleosporaceae) collected from Apiaceae in Algeria. MycoKeys 2025, 113, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkilinc, H.; Sarpakaya, K.; Kurt, S.; Can, C.; Polatbilek, H.; Yasar, A.; Sevinc, U.; Uysal, A.; Konukoglu, F. Pathogenicity, morpho-species and mating types of Alternaria spp. causing Alternaria blight in Pistacia spp. in Turkey. Phytoparasitica 2017, 45, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, F.; Riolo, M.; Sanzani, S.M.; Mincuzzi, A.; Ippolito, A.; Siciliano, I.; Pane, A.; Gullino, M.L.; Cacciola, S.O. Characterization of Alternaria species associated with heart rot of pomegranate fruit. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salotti, I.; Giorni, P.; Battilani, P. Biology, ecology, and epidemiology of Alternaria species affecting tomato: Ground information for the development of a predictive model. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1430965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.T.; Long, J.-H.; Liu, J.Q.; Zhang, R.-Z.; Xu, L.L.; Wang, J.-J.; Wei, X.K.; White, J.F.; Kamran, M.; Cui, H.W.; et al. Characterization and pathogenicity of Alternaria species associated with leaf spot on Plantago lanceolata in Sichuan Province, China. Plant Pathol. 2024, 73, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, P.M.; Arbes, S.J., Jr.; Sever, M.; Jaramillo, R.; Cohn, R.D.; London, S.J.; Zeldin, D.C. Exposure to Alternaria alternata in US homes is associated with asthma symptoms. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, C.; Johnson, E.M.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.J. Alternaria species infection in nine domestic cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.; Borges-Costa, J.; Soares-Almeida, L.; Filipe, P.; Neves, F.; Santana, A.; Guerra, J.; Kutzner, H. Cutaneous alternariosis caused by Alternaria infectoria: Three cases in kidney transplant patients. Healthcare 2013, 1, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, M.; Gupta, S.K.; Swapnil, P.; Zehra, A.; Dubey, M.K.; Upadhyay, R.S. Alternaria toxins: Potential virulence factors and genes related to pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Kamble, U.; Ghosh, G.; Prasad, A.; Chowdhary, A. Invasive rhinosinusitis due to Alternaria alternata and Rhizopus arrhizus mixed infection: A case report and review. Int. J. Infect. 2017, 4, e42127. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Yoo, S.J.; Yoo, J.R.; Seo, K.B. The first case report of thorn-induced Alternaria alternata infection of the hand in an immunocompetent host. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Liu, Z.; Shen, H. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Alternaria section Alternaria. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 134, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minaeva, L.P.; Markova, Y.M.; Sedova, I.B.; Chaly, Z.A. Micromycetes of the genus Alternaria are producers of emerging mycotoxins: Analysis of profile and toxinogenic potential in vitro. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lücking, R.; Aime, M.C.; Robbertse, B.; Miller, A.N.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Aoki, T.; Cardinali, G.; Crous, P.W.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Geiser, D.M.; et al. Unambiguous identification of fungi: Where do we stand and how accurate and precise is fungal DNA barcoding? IMA Fungus 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.K.; Verma, R.K.; Avasthi, S.; Sushma; Bohra, Y.; Devadatha, B.; Niranjan, M.; Suwannarach, N. Current insight into traditional and modern methods in fungal diversity estimates. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourvar, M.; Charylo, K.R.; Frandsen, R.J.N.; Brewer, S.S.; Hoof, J.B. Automated fungal identification with deep learning on time-lapse images. Information 2025, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouris, J.; Konstantinidis, K.; Pyrri, I.; Papageorgiou, E.G.; Voyiatzaki, C. FungID: Innovative fungi identification method with chromogenic profiling of colony color patterns. Pathogens 2025, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, K.B.; Rajderkar, N.R. New species of Alternaria from Marathwada (India). Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 1964, 23, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Q.; Zhang, T.Y. Two new species of Alternaria from China. Mycol. Res. 1997, 101, 1257–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.G. Alternaria roseogrisea, a new species from achenes of Helianthus annuus L. (Sunflower). Mycotaxon 2008, 103, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gannibal, P.B.; Gomzhina, M.M. Revision of Alternaria sections Pseudoulocladium and Ulocladioides: Assessment of species boundaries, determination of mating-type loci, and identification of Russian strains. Mycologia 2024, 116, 744–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursafar, A.; Ghosta, Y.; Orina, A.S.; Gannibal, P.B.; Javan-Nikkhah, M.; Lawrence, D.P. Taxonomic study on Alternaria sections Infectoriae and Pseudoalternaria associated with black (sooty) head mold of wheat and barley in Iran. Mycol. Prog. 2018, 17, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturrieta-González, I.; Pujol, I.; Iftimie, S.; Gracía, D.; Morente, V.; Queralt, R.; Guevara-Suarez, M.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Ballester, F.; Hernández-Restrepo, M.; et al. Polyphasic identification of three new species in Alternaria section Infectoria causing human cutaneous infection. Mycoses 2020, 63, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.K.M.; Hyde, K.D. Diversity of fungi on six species of Gramineae and one species of Cyperaceae in Hong Kong. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, C.T.; Carter, R. The significance of Cyperaceae as weeds. In Sedges: Uses, Diversity, and Systematics of the Cyperaceae; Naczi, R.C.F., Ford, B.A., Eds.; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2008; pp. 15–101. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, M. Phylogenetic congruence of parasitic smut fungi (Anthracoidea, Anthracoideaceae) and their host plants (Carex, Cyperaceae): Cospeciation or host-shift speciation? Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Tripathi, A.; Tripathi, D.K.; Chauhan, D.K. Role of sedges (Cyperaceae) in wetlands, environmental cleaning and as food material: Possibilities and future perspectives. In Plant-Environment Interaction: Responses and Approaches to Mitigate Stress; Azooz, M.M., Ahmad, P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Bognor Regis, UK, 2016; pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, K.; Schön, M.E.; Ziegler, R.; Lutz, M.; Shivas, R.S.; Piątek, M.; Garnica, S. The origin and diversification of the Enthorrhizales: Deep evolutionary roots but recent specialization with a phylogenetic and phenotypic split between associates of the Cyperaceae and Juncaceae. Org. Divers. Evol. 2019, 19, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léveillé-Bourret, É.; Eggertson, Q.; Hambleton, S.; Starr, J.R. Cryptic diversity and significant cophylogenetic signal detected by DNA barcoding the rust fungi (Pucciniaceae) of Cyperaceae-Juncaceae. J. Syst. Evol. 2021, 59, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portalanza, D.; Acosta-Mejillones, A.; Alcivar, J.; Colorado, T.; Guaita, J.; Montero, L.; Villao-Uzho, L.; Santos-Ordonez, E. Fungal community dynamics in Cyperus rotundus: Implications for Rhizophora mangle in a mangrove ecosystem. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, A.; Heidarian, Z.; Ghosta, Y.; Alavi, Z.; Alavi, F.; Manamgoda, D.S.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Rampelotto, P.H. Morphological and molecular characterization of Curvularia species from Iran, with description of two novel species and two new records. Mycologia 2025, 117, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, A.; Heidarian, Z.; Ghosta, Y.; Alavi, Z.; Alavi, F.; Manamgoda, D.S.; Kumla, J.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Rampelotto, P.H.; Suwannarach, N. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses of Bipolaris species associated with Poales and Asparagales host plants in Iran. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1520125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.P.; Madrid, H.; Crous, P.W.; Shivas, R.G. Johnalcornia gen. et. comb. nov., and nine new combinations in Curvularia based on molecular phylogenetic analysis. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2014, 43, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Loci | Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Direction | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | NS1 | GTAGTCATATGCTTGTCTC | Forward | [40] |

| NS4 | CTTCCGTCAATTCCTTTAAG | Reverse | ||

| ITS | ITS1 | TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG | Forward | [40] |

| ITS4 | TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC | Reverse | ||

| LSU | LR0R | GTACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC | Forward | [40] |

| LR5 | TCCTGAGGGAAACTTCG | Reverse | ||

| GAPDH | gpd1 | CAACGGCTTCGGTCGCATTG | Forward | [41] |

| gpd2 | GCCAAGCAGTTGGTTGTG | Reverse | ||

| RPB2 | RPB2-5F2 | GGGGWGAYCAGAAGAAGGC | Forward | [42] |

| RPB2-7cR | CCCATRGCTTGTYYRCCCAT | Reverse | [43] | |

| TEF1 | EF1-728F | CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG | Forward | [44] |

| EF1-986R | TACTTGAAGGAACCCTTACC | Reverse |

| Species Name | Section | Collection No. | Country | Host/Substrate | GenBank Accession Numbers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | ITS | LSU | GAPDH | RPB2 | TEF1 | |||||

| Alternaria abundans | Chalastospora | CBS 534.83 T | New Zealand | Fragaria sp. | KC584581 | JN383485 | KC584323 | KC584154 | KC584448 | KC584707 |

| A. alternantherae | Alternantherae | CBS 1243s92 | China | Solanum melongena | KC584506 | KC584179 | KC584251 | KC584096 | KC584374 | KC584633 |

| A. alternariae | Ulocladium | CBS 126989 T | USA | Daucus carota | KC584604 | AF229485 | KC584346 | AY278815 | KC584470 | KC584730 |

| A. alternata | Alternaria | CBS 916.96 T | India | Arachis hypogaea | KC584507 | AF347031 | DQ678082 | AY278808 | KC584375 | KC584634 |

| A. arborescens | Alternaria | CBS 102605 T | USA | Lycopersicon esculentum | KC584509 | AF347033 | KC584253 | AY278810 | KC584377 | KC584636 |

| A. argyranthemi | - | CBS 116530 T | New Zealand | Argyranthemum sp. | KC584510 | KC584181 | KC584254 | KC584098 | KC584378 | KC584637 |

| A. arrhenatheri | Pseudoalternaria | LEP 140372 T | USA | Arrhenatherum elatius | - | JQ693677 | - | JQ693635 | - | - |

| A. aspera | Pseudoulocladium | CBS 115269 T | Japan | Pistacia vera | KC584607 | KC584242 | KC584349 | KC584166 | KC584474 | KC584734 |

| A. atra | Ulocladioides | CBS 195.67 T | USA | Soil | KC584608 | AF229486 | KC584350 | KC584167 | KC584475 | KC584735 |

| A. avenicola | Panax | CBS 121459 T | Norway | Avena sp. | KC584512 | KC584183 | KC584256 | KC584100 | KC584380 | KC584639 |

| A. avrinica | Iraniana | IRAN 4772C T | Iran | Juncus sp. | PV435164 | PV435148 | PV435156 | PV443215 | PV443231 | PV443223 |

| A. avrinica | Iraniana | IRAN 5031C | Iran | Juncus sp. | PV435165 | PV435149 | PV435157 | PV443216 | PV443232 | PV443224 |

| A. avrinica | Iraniana | FCCUU 1419 | Iran | Carex sp. | PV435166 | PV435150 | PV435158 | PV443217 | PV443233 | PV443225 |

| A. avrinica | Iraniana | FCCUU 1420 | Iran | Juncus sp. | PV435167 | PV435151 | PV435159 | PV443218 | PV443234 | PV443226 |

| A. bornmuelleri | Undifilum | DAOM 231361 T | Austria | Securigera varia | KC584624 | FJ357317 | KC584366 | FJ357305 | KC584491 | KC584751 |

| A. botryospora | Embellisioides | CBS 478.90 T | New Zealand | Leptinella dioica | KC584594 | MH862228 | KC584336 | AY278831 | KC584461 | KC584720 |

| A. botrytis | Ulocladium | CBS 197.67 T | USA | Contaminant | KC584609 | KC584243 | KC584351 | KC584168 | KC584476 | KC584736 |

| A. brassicae | - | CBS 116528 R | USA | Brassica oleracea | KC584514 | KC584185 | KC584258 | KC584102 | KC584382 | KC584641 |

| A. brassicicola | Brassicicola | CBS 118699 R | USA | Brassica oleracea | KC584515 | JX499031 | KC584259 | KC584103 | KC584383 | KC584642 |

| A. brassicifolii | - | CNU 111118 T | Korea | Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis | - | JQ317188 | - | KM821537 | - | - |

| A. breviramosa | Chalastospora | CBS 121331 T | Australia | Triticum sp. | KC584574 | FJ839608 | KC584318 | KC584148 | KC584442 | KC584700 |

| A. cantlous | Ulocladioides | CBS 123007 T | China | Cucumis melo | KC584612 | KC584245 | KC584354 | KC584171 | KC584479 | KC584739 |

| A. caricicola | Nimbya | IRAN 3418C T | Iran | Carex sp. | - | MK508871 | - | MK505392 | MT187279 | MT187265 |

| A. caricis | Nimbya | CBS 480.90 T | USA | Carex hoodii | KC584600 | AY278839 | KC584342 | AY278826 | KC584467 | KC584726 |

| A. celosiicola | Alternantherae | MAFF 243058 | Japan | Celosia argentea var. plumosa | - | AB678217 | - | AB744033 | LC476781 | LC480205 |

| A. cetera | Chalastospora | CBS 121340 T | Australia | Elymus scabrus | KC584573 | JN383482 | KC584317 | AY562398 | KC584441 | KC584699 |

| A. chartarum | Pseudoulocladium | CBS 200.67 T | Canada | Populus sp. | KC584614 | AF229488 | KC584356 | KC584172 | KC584481 | KC584741 |

| A. cheiranthi | Cheiranthus | CBS 109384R | Italy | Cheiranthus cheiri | KC584519 | AF229457 | KC584263 | KC584107 | KC584387 | KC584646 |

| A. chlamydospora | Phragmosporae | CBS 491.72 T | Egypt | Soil | KC584520 | KC584189 | KC584264 | KC584108 | KC584388 | KC584647 |

| A. chlamydosporigena | Embellisia | CBS 341.71 R | USA | Air | KC584584 | KC584231 | KC584326 | KC584156 | KC584451 | KC584710 |

| A. cinerariae | Sonchi | CBS 116495 R | USA | Ligularia sp. | KC584521 | KC584190 | KC584265 | KC584109 | KC584389 | KC584648 |

| A. conjuncta | Infectoriae | CBS 196.86 T | Switzerland | Pastinaca sativa | KC584522 | FJ266475 | KC584266 | AY562401 | KC584390 | KC584649 |

| A. conoidea | Brassicicola | CBS 132.89 | Saudi Arabia | Ricinus communis | KC584585 | FJ348226 | KC584327 | FJ348227 | KC584452 | KC584711 |

| A. cucurbitae | Ulocladioides | CBS 483.81R | New Zealand | Cucumis sativus | KC584616 | FJ266483 | KC584358 | AY562418 | KC584483 | KC584743 |

| A. cumini | Eureka | CBS 121329 T | India | Cuminum cyminum | KC584523 | KC584191 | KC584267 | KC584110 | KC584391 | KC584650 |

| A. cypericola | Nimbya | IRAN 3423C T | Iran | Cyperus sp. | - | MT176120 | - | MT187250 | MT187276 | MT187262 |

| A. dauci | Porri | CBS 111.38 T | Italy | Daucus carota | - | KJ718158 | - | KJ718005 | KJ718331 | KJ718506 |

| A. daucifolii | Alternaria | CBS 118812 T | USA | Daucus carota | KC584525 | KC584193 | KC584269 | KC584112 | KC584393 | KC584652 |

| A. dennisii | - | CBS 476.90 T | Isle of Man | Senecio jacobaea | KC584587 | JN383488 | KC584329 | JN383469 | KC584454 | KC584713 |

| A. dennisii | - | CBS 110533 | New Zealand | Senecio jacobaea | KC584586 | KC584232 | KC584328 | KC584157 | KC584453 | KC584712 |

| A. dianthicola | Dianthicola | CBS 116491 R | New Zealand | Dianthus × allwoodii | KC584526 | KC584194 | KC584270 | KC584113 | KC584394 | KC584653 |

| A. didymospora | Phragmosporae | CBS 766.79 | Adriatic Sea | Seawater | KC584588 | FJ357312 | KC584330 | FJ357300 | KC584455 | KC584714 |

| A. elegans | Dianthicola | CBS 109159 T | Burkina Faso | Lycopersicon esculentum | KC584527 | KC584195 | KC584271 | KC584114 | KC584395 | KC584654 |

| A. embellisia | Embellisia | CBS 339.71 R | USA | Allium sativum | KC584582 | KC584230 | KC584324 | KC584155 | KC584449 | KC584708 |

| A. ershadii | Pseudoalternaria | IRAN 3275C | Iran | Triticum aestivum | - | MK829647 | - | MK829645 | - | - |

| A. eryngii | Panax | CBS 121339 R | - | Eryngium sp. | KC584529 | JQ693661 | KC584273 | AY562416 | KC584397 | KC584656 |

| A. euphorbiicola | Euphorbiicola | CBS 119410 R | USA | Euphorbia pulcherrima | - | KJ718173 | - | KJ718018 | KJ718346 | KJ718521 |

| A. euphorbiicola | Euphorbiicola | CBS 133874 | USA | Euphorbia hyssopifolia | - | KJ718174 | - | KJ718019 | KJ718347 | KJ718522 |

| A. eureka | Eureka | CBS 193.86 T | Australia | Medicago rugosa | KC584589 | JN383490 | KC584331 | JN383471 | KC584456 | KC584715 |

| A. gypsophilae | Gypsophilae | CBS 107.41 T | Unknown | Gypsophila elegans | KC584533 | KC584199 | KC584277 | KC584118 | KC584401 | KC584660 |

| A. helianthiinficiens | Helianthiinficientes | CBS 117370 R | UK | Helianthus annuus | KC584534 | KC584200 | KC584278 | KC584119 | KC584402 | KC584661 |

| A. helianthiinficiens | Helianthiinficientes | CBS 208.86 T | USA | Helianthus annuus | KC584535 | JX101649 | KC584279 | KC584120 | KC584403 | EU130548 |

| A. heterospora | Ulocladioides | CBS 123376 T | China | Lycopersicon esculentum | KC584621 | KC584248 | KC584363 | KC584176 | KC584488 | KC584748 |

| A. heyranica | Nimbya | IRAN 3516C T | Iran | Carex sp. | - | MT176114 | - | MT187244 | MT187270 | MT187256 |

| A. hyacinthi | Embellisioides | CBS 416.71 T | Netherlands | Hyacinthus orientalis | KC584590 | KC584233 | KC584332 | KC584158 | KC584457 | KC584716 |

| A. indefessa | Cheiranthus | CBS 536.83 T | USA | Soil | KC584591 | KC584234 | KC584333 | KC584159 | KC584458 | KC584717 |

| A. infectoria | Infectoriae | CBS 210.86 T | UK | Triticum aestivum | KC584536 | DQ323697 | KC584280 | AY278793 | KC584404 | KC584662 |

| A. iraniana | Iraniana | IRAN 5030C T | Iran | Juncus sp. | - | PV435152 | PV435160 | PV443219 | PV443235 | PV443227 |

| A. iraniana | Iraniana | FCCUU 1421 | Iran | Juncus sp. | - | PV435153 | PV435161 | PV443220 | PV443236 | PV443228 |

| A. iraniana | Iraniana | FCCUU 1422 | Iran | Juncus sp. | - | PV435154 | PV435162 | PV443221 | PV443237 | PV443229 |

| A. iraniana | Iraniana | FCCUU 1423 | Iran | Juncus sp. | - | PV435155 | PV435163 | PV443222 | PV443238 | PV443230 |

| A. japonica | Japonicae | CBS 118390 R | USA | Brassica chinensis | KC584537 | KC584201 | KC584281 | KC584121 | KC584405 | KC584663 |

| A. junci-acuti | Nimbya | IRAN 3512C T | Iran | Juncus acutus | - | MT176113 | - | MT187243 | MT187269 | MT187255 |

| A. kordkuyana | Pseudoalternaria | IRAN 2764C T | Iran | Triticum aestivum | - | MF033843 | - | MF033826 | - | - |

| A. kulundii | Soda | M313 T | Russia | Soil | KJ443087 | KJ443262 | KJ443132 | KJ649618 | KJ443176 | - |

| A. leucanthemi | Teretispora | CBS 422.65 R | USA | Chrysanthemum maximum | KC584606 | KC584241 | KC584348 | KC584165 | KC584473 | KC584733 |

| A. leucanthemi | Teretispora | CBS 421.65 T | Netherlands | Chrysanthemum maximum | KC584605 | KC584240 | KC584347 | KC584164 | KC584472 | KC584732 |

| A. limaciformis | Phragmosporae | CBS 481.81 T | UK | Soil | KC584539 | KC584203 | KC584283 | KC584123 | KC584407 | KC584665 |

| A. longipes | Alternaria | CBS 540.94 R | USA | Nicotiana tabacum | KC584541 | AY278835 | KC584285 | AY278811 | KC584409 | KC584667 |

| A. mimicula | Brassicicola | CBS 118696 T | USA | Lycopersicon esculentum | KC584543 | FJ266477 | KC584287 | AY562415 | KC584411 | KC584669 |

| A. nepalensis | Japonicae | CBS 118700 T | Nepal | Brassica sp. | KC584546 | KC584207 | KC584290 | KC584126 | KC584414 | KC584672 |

| A. nobilis | Gypsophilae | CBS 116490 R | New Zealand | Dianthus caryophyllus | KC584547 | KC584208 | KC584291 | KC584127 | KC584415 | KC584673 |

| A. obovoidea | Ulocladioides | CBS 101229 | New Zealand | Cucumis sativus | KC584618 | FJ266487 | KC584360 | FJ266498 | KC584485 | KC584745 |

| A. omanensis | Omanenses | SQUCC 15560 | Oman | dead wood | MK878560 | MK878563 | MK878557 | MK880900 | MK880894 | MK880897 |

| A. omanensis | Omanenses | SQUCC 13580 T | Oman | dead wood | MK878559 | MK878562 | MK878556 | MK880899 | MK880893 | MK880896 |

| A. oregonensis | Infectoriae | CBS 542.94 T | USA | Triticum aestivum | KC584548 | FJ266478 | KC584292 | FJ266491 | KC584416 | KC584674 |

| A. oudemansii | Ulocladium | CBS 114.07 T | - | - | KC584619 | FJ266488 | KC584361 | KC584175 | KC584486 | KC584746 |

| A. panax | Panax | CBS 482.81 R | USA | Aralia racemosa | KC584549 | KC584209 | KC584293 | KC584128 | KC584417 | KC584675 |

| A. papavericola | Crivellia | CBS 116606 T | USA | Papaver somniferum | KC584579 | FJ357310 | KC584321 | FJ357298 | KC584446 | KC584705 |

| A. penicillata | Crivellia | CBS 116608 T | Austria | Papaver rhoeas | KC584572 | FJ357311 | KC584316 | FJ357299 | KC584440 | KC584698 |

| A. penicillata | Crivellia | CBS 116607 T | Austria | Papaver rhoeas | KC584580 | KC584229 | KC584322 | KC584153 | KC584447 | KC584706 |

| A. perpunctulata | Alternantherae | CBS 115267 T | USA | Alternanthera philoxeroides | KC584550 | KC584210 | KC584294 | KC584129 | KC584418 | KC584676 |

| A. petroselini | Radicina | CBS 112.41 T | - | Petroselinum sativum | KC584551 | KC584211 | KC584295 | KC584130 | KC584419 | KC584677 |

| A. petuchovskii | Soda | M304 T | Russia | Alkaline soil | KJ443079 | KJ443254 | KJ443124 | KJ649616 | KJ443170 | - |

| A. photistica | Panax | CBS 212.86 T | UK | Digitalis purpurea | KC584552 | KC584212 | KC584296 | KC584131 | KC584420 | KC584678 |

| A. phragmospora | Phragmosporae | CBS 274.70 | Netherlands | Soil | KC584595 | JN383493 | KC584337 | JN383474 | KC584462 | KC584721 |

| A. porri | Porri | CBS 116699 T | USA | Allium cepa | - | KJ718218 | - | KJ718053 | KJ718391 | KJ718564 |

| A. proteae | Embellisioides | CBS 475.90 T | Australia | Protea sp. | KC584597 | AY278842 | KC584339 | KC584161 | KC584464 | KC584723 |

| A. protenta | Porri | CBS 116651 R | USA | Solanum tuberosum | KC584562 | KC584217 | KC584306 | KC584139 | KC584430 | KC584688 |

| A. pseudorostrata | Porri | CBS 119411 T | USA | Euphorbia pulcherrima | KC584554 | JN383483 | KC584298 | AY562406 | KC584422 | KC584680 |

| A. radicina | Radicina | CBS 245.67 T | USA | Daucus carota | KC584555 | KC584213 | KC584299 | KC584133 | KC584423 | KC584681 |

| A. rosae | Pseudoalternaria | CBS 121341 T | New Zealand | Rosa rubiginosa | - | JQ693639 | - | JQ646279 | - | - |

| A. scirpicola | Nimbya | CBS 481.90 | UK | Scirpus sp. | KC584602 | KC584237 | KC584344 | KC584163 | KC584469 | KC584728 |

| A. scirpinfestans | Nimbya | EGS 49-185 | USA | Scirpus acutus | - | JN383499 | - | JN383480 | - | - |

| A. scirpivora | Nimbya | EGS 50-021 | USA | Scirpus acutus | - | JN383500 | - | JN383481 | - | - |

| A. scirpivora | Nimbya | IRAN 3421C | Iran | Scirpus acutus | - | MT176118 | - | MT187248 | MT187274 | MT187260 |

| A. selini | Radicina | CBS 109382 T | Saudi Arabia | Petroselinum crispum | KC584558 | AF229455 | KC584302 | AY278800 | KC584426 | KC584684 |

| A. septospora | Pseudoulocladium | CBS 109.38 | Italy | Wood | KC584620 | FJ266489 | KC584362 | FJ266500 | KC584487 | KC584747 |

| A. shukurtuzii | Soda | M307 T | Russia | Alkaline soil | KJ443082 | KJ443257 | KJ443127 | KJ649620 | KJ443172 | - |

| A. simsimi | Dianthicola | CBS 115265 T | Argentina | Sesamum indicum | KC584560 | JF780937 | KC584304 | KC584137 | KC584428 | KC584686 |

| A. smyrnii | Radicina | CBS 109380 R | UK | Smyrnium olusatrum | KC584561 | AF229456 | KC584305 | KC584138 | KC584429 | KC584687 |

| A. soliaridae | - | CBS 118387 T | USA | Soil | KC584563 | KC584218 | KC584307 | KC584140 | KC584431 | KC584689 |

| A. sonchi | Sonchi | CBS 119675 R | Canada | Sonchus asper | KC584565 | KC584220 | KC584309 | KC584142 | KC584433 | KC584691 |

| A. tellustris | Embellisia | CBS 538.83 T | USA | Soil | KC584598 | MH861643 | KC584340 | AY562419 | KC584465 | KC584724 |

| A. thalictrigena | - | CBS 121712 T | Germany | Thalictrum sp. | KC584568 | EU040211 | KC584312 | KC584144 | KC584436 | KC584694 |

| A. triglochinicola | Eureka | CBS 119676 T | Australia | Triglochin procera | KC584569 | KC584222 | KC584313 | KC584145 | KC584437 | KC584695 |

| A. tumida | Embellisioides | CBS 539.83 T | Australia | Triticum aestivum | KC584599 | FJ266481 | KC584341 | FJ266493 | KC584466 | KC584725 |

| A. vaccariicola | Gypsophilae | CBS 118714 T | USA | Vaccaria hispanica | KC584571 | KC584224 | KC584315 | KC584147 | KC584439 | KC584697 |

| Alternariaster bidentis | - | CBS 134021 T | Brazil | Bidens sulphurea | - | KC609333 | KC609341 | KC609325 | KC609347 | - |

| Alternariaster helianthi | - | CBS 119672 R | USA | Helianthus sp. | KC584626 | KC609337 | KC584368 | KC609329 | KC584493 | - |

| Amarenomyces ammophilae | - | CBS 114595 | Sweden | Ammophila arenaria | GU296185 | KF766146 | GU301859 | - | GU371724 | - |

| Ascochyta pisi | - | CBS 126.54 | Netherlands | Pisum sativum | EU754038 | - | DQ678070 | - | DQ677967 | - |

| Bipolaris maydis | - | CBS 137271 T | USA | Zea mays | - | AF071325 | KM243280 | KM034846 | - | - |

| Bipolaris oryzae | - | CBS 157.50 | Indonesia | Oryza sativa | - | HF934931 | HF934870 | HG779090 | HF934833 | - |

| Bipolaris sorokiniana | - | CBS 480.74 | South Africa | Tribulus terrestris | - | KJ909771 | KM243282 | KM034827 | - | - |

| Boeremia exigua | - | CBS 431.74 | Netherlands | Solanum tuberosum | EU754084 | FJ427001 | EU754183 | - | GU371780 | - |

| Calophoma complanata | - | CBS 268.92 | Netherlands | Anglica sylvestris | EU754081 | FJ515608 | EU754180 | - | GU371778 | - |

| Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum | - | CBS 216.75 | Germany | Anthyllis vulneraria | EU754045 | KF251148 | EU754144 | - | GU371777 | - |

| Cicatricea salina | - | CBS 302.84 T | North Sea, Skagerrak | Cancer pagurus | KC584583 | JN383486 | KC584325 | JN383467 | KC584450 | KC584709 |

| Cnidariophoma eilatica | - | CPC 44117 T | Israel | Stylophora pistillata | - | OQ628480 | OQ629062 | - | OQ627943 | - |

| Cochliobolus heterostrophus | - | CBS 134.39 | – | Zea mays | AY544727 | DQ491489 | AY544645 | - | DQ247790 | - |

| Comoclathris compressa | - | CBS 156.53 | USA | Castilleja miniata | KC584630 | - | KC584372 | - | KC584497 | - |

| Comoclathris incompta | - | CBS 467.76 | Greece | Olea europaea | GU238220 | - | GU238087 | - | KC584504 | - |

| Comoclathris typhicola | - | CBS 132.69 | Netherlands | Typha angustifolia | JF740105 | - | JF740325 | - | KC584505 | - |

| Curvularia affinis | - | CBS 154.34 T | Java | Manihot utilissima | - | HG778981 | HG779028 | HG779126 | HG779159 | - |

| Curvularia hawaiiensis | - | BRIP 11987 T | USA | Oryza sativa | - | KJ415547 | KJ415502 | KJ415399 | - | - |

| Curvularia lunata | - | CBS 730.96 T | USA | Human lung biopsy | - | JX256429 | JX256396 | JX276441 | HF934813 | - |

| Decorospora gaudefroyi | - | CBS 332.63 | France | Unknown | AF394542 | MH858305 | MH869915 | - | - | - |

| Decorospora gaudefroyi | - | CBS 250.60 | UK | Unknown | - | MH857974 | MH869526 | - | - | - |

| Dichotomophthora lutea | - | CBS 145.57 T | Unknown | Unknown | - | MH857676 | NG069497 | LT990663 | LT990634 | - |

| Dichotomophthora portulacae | - | CBS 174.35 T | Unknown | Unknown | - | NR158421 | MH867137 | LT990668 | LT990638 | - |

| Didymella glomerata | - | CBS 528.66 | Netherlands | Chrysanthemum sp. | EU754085 | FJ427013 | EU754184 | - | GU371781 | - |

| Didymella maydis | - | CBS 588.69 T | USA | Zea mays | EU754093 | FJ427086 | EU754192 | - | GU371782 | - |

| Exserohilum corniculatum | - | BRIP 11426 T | Australia | Oryza sativa | - | LT837453 | LT883391 | LT883533 | LT852480 | - |

| Exserohilum khartoumensis | - | IMI 249194 IsoT | Sudan | Sorghum bicolor var. mayo | - | LT837461 | LT715619 | LT715888 | LT852490 | - |

| Exserohilum turcicum | - | CBS 690.71 ET | Germany | Zea mays | - | LT837487 | LT883415 | LT882581 | - | - |

| Exserohilum turcicum | - | CBS 387.58 | USA | Zea mays | - | MH857820 | LT883412 | LT883554 | LT852514 | - |

| Halojulella avicenniae | - | BCC 18422 | Thailand | Mangrove wood | GU371831 | - | GU371823 | - | GU371787 | - |

| Heterosporicola chenopodii | - | CBS 115.96 | Netherlands | Chenopodium album | EU754089 | JF740227 | EU754188 | - | GU371775 | - |

| Johnalcornia aberrans | - | BRIP 16281 T | Australia | Eragrostis parviflora | - | KJ415522 | KJ415475 | KJ415424 | - | - |

| Leptosphaeria maculans | - | DAOM 229267 | France | Brassica sp. | DQ470993 | KT225526 | DQ470946 | - | DQ470894 | - |

| Leptosphaerulina australis | - | CBS 317.83 | Indonesia | Eugenia aromatica | GU296160 | GU237829 | GU301830 | - | GU371790 | - |

| Loratospora aestuarii | - | JK 5535B | USA | Juncus roemerianus | GU296168 | MH863024 | GU301838 | - | GU371760 | - |

| Neocamarosporium betae | - | CBS 109410 | Netherlands | Beta vulgaris | EU754079 | KY940790 | EU754178 | - | GU371774 | - |

| Neocamarosporium calvescens | - | CBS 246.79 | Germany | Atriplex hastata | EU754032 | KY940774 | EU754131 | - | KC584500 | - |

| Neocamarosporium goegapense | - | CPC 23676 T | South Africa | Mesembryanthemum sp. | - | KJ869163 | KJ869220 | - | - | - |

| Neophaeosphaeria filamentosa | - | CBS 102202 | Mexico | Yucca rostrata | GQ387516 | JF740259 | GQ387577 | - | GU371773 | - |

| Neostemphylium polymorphum | - | FMR 17886 T | Spain | Fluvial sediment | - | OU195609 | OU195892 | OU195960 | OU196009 | ON368192 |

| Neostemphylium polymorphum | - | FMR 17889 | Spain | Fluvial sediment | - | OU195610 | OU195914 | OU195977 | OU196957 | ON368193 |

| Ophiosphaerella herpotricha | - | CBS 620.86 | Switzerland | Bromus erectus | DQ678010 | - | DQ678062 | - | DQ677958 | - |

| Paradendryphiella arenariae | - | CBS 181.58 T | France | Coastal sand | KC793336 | KF156010 | KC793338 | - | DQ470924 | - |

| Paradendryphiella salina | - | CBS 142.60 | UK | Spartina sp. | KC793337 | DQ411540 | KC793339 | - | KC793340 | - |

| Paraleptosphaeria dryadis | - | CBS 643.86 | Switzerland | Dryas octopetala | KC584632 | JF740213 | GU301828 | - | GU371733 | - |

| Phaeosphaeria avenaria | - | DAOM 226215 | Canada | Avena sativa | AY544725 | - | AY544684 | - | DQ677941 | - |

| Phaeosphaeria eustoma | - | CBS 573.86 | Switzerland | Dactylis glomerata | DQ678011 | - | DQ678063 | - | DQ677959 | - |

| Phoma herbarum | - | CBS 276.37 | Sweden | Wood pulp | DQ678014 | - | DQ678066 | - | DQ677962 | - |

| Porocercospora seminalis | - | CBS 134907 | USA | Bouteloua dactyloides | - | HF934941 | HF934862 | - | HF934843 | - |

| Porocercospora seminalis | - | CPC 213.49 | USA | Bouteloua dactyloides | - | HF934945 | HF934861 | - | HF934845 | - |

| Pyrenophora avenicola | - | CBS 307.84 T | Sweden | Avena sp. | - | MK539972 | MK540042 | MK540180 | - | - |

| Pyrenophora phaeocomes | - | DAOM 222769 | Switzerland | Calamagrostis villosa | DQ499595 | JN943649 | DQ499596 | - | DQ497614 | - |

| Scleromyces submersus | - | FMR 18289 T | Spain | Fluvial sediment | - | OU195893 | OU195959 | OU196008 | OU197244 | OU196982 |

| Setomelanomma holmii | - | CBS 110217 | USA | Picea pungens | GU296196 | KT389542 | GU301871 | - | GU371800 | - |

| Stemphylium botryosum | - | CBS 714.68 T | Canada | Medicago sativa | KC584603 | KC584238 | KC584345 | AF443881 | AF107804 | KC584729 |

| Stemphylium vesicarium | - | CBS 191.86 T | India | Medicago sativa | GU238232 | KC584239 | GU238160 | AF443884 | KC584471 | KC584731 |

| Tamaricicola muriformis | - | MFLUCC 150488 | Italy | Tamarix sp. | KU870909 | KU752187 | KU561879 | - | KU820870 | - |

| Tamaricicola muriformis | - | MFLUCC 150489 | Italy | Tamarix sp. | KU870910 | KU752188 | KU729857 | - | - | - |

| Typhicola typharum | - | CBS 145043 NT | Germany | Leaf of Typha sp. | - | MK442590 | MK442530 | - | MK442666 | - |

| Analysis | Region/Gene | Parameter | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Taxa | Total Characters | Constant Sites | Variable Sites | Parsimony Informative Sites | Parsimony Uninformative Sites | AIC Substitution Model * | Lset nst, Rates | −lnL | ||

| First analysis (suborder Pleosporineae) | SSU | 122 | 1373 | 1194 | 179 | 69 | 110 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 3432.2908 |

| ITS | 158 | 437 | 266 | 171 | 143 | 28 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 5161.6314 | |

| LSU | 150 | 869 | 686 | 183 | 113 | 70 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 3733.1211 | |

| GAPDH | 130 | 534 | 302 | 232 | 207 | 25 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 8174.018 | |

| RPB2 | 150 | 837 | 359 | 478 | 419 | 59 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 21800.52 | |

| Combined | 167 | 4050 | 2807 | 1243 | 951 | 292 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 44380.022 | |

| Second analysis (All Alternaria sections) | SSU | 89 | 1022 | 982 | 40 | 27 | 13 | GTR+I | 6, propinv | 1813.347845 |

| ITS | 110 | 457 | 336 | 121 | 95 | 26 | SYM+I+G | 6, invgamma | 2892.446526 | |

| LSU | 93 | 851 | 798 | 53 | 36 | 17 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 1734.095321 | |

| GAPDH | 110 | 557 | 334 | 223 | 195 | 28 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 6256.718561 | |

| RPB2 | 103 | 799 | 500 | 299 | 285 | 14 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 9217.307515 | |

| TEF1 | 100 | 317 | 155 | 162 | 139 | 23 | GTR+I+G | 6, invgamma | 3802.639587 | |

| Combined | 110 | 4003 | 3105 | 898 | 777 | 121 | SYM+I+G | 6, invgamma | 27448.64266 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmadpour, A.; Ghosta, Y.; Alavi, Z.; Alavi, F.; Hamidi, L.M.; Rampelotto, P.H. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a New Section and Two New Species of Alternaria from Iran. Life 2025, 15, 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060870

Ahmadpour A, Ghosta Y, Alavi Z, Alavi F, Hamidi LM, Rampelotto PH. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a New Section and Two New Species of Alternaria from Iran. Life. 2025; 15(6):870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060870

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmadpour, Abdollah, Youbert Ghosta, Zahra Alavi, Fatemeh Alavi, Leila Mohammadi Hamidi, and Pabulo Henrique Rampelotto. 2025. "Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a New Section and Two New Species of Alternaria from Iran" Life 15, no. 6: 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060870

APA StyleAhmadpour, A., Ghosta, Y., Alavi, Z., Alavi, F., Hamidi, L. M., & Rampelotto, P. H. (2025). Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a New Section and Two New Species of Alternaria from Iran. Life, 15(6), 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060870