Adaptive Neuromuscular Co-Contraction Strategies Under Varying Approach Speeds and Distances During Single-Leg Jumping: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Experimental Design

2.2. Instrumentation, Setup, and Synchronization

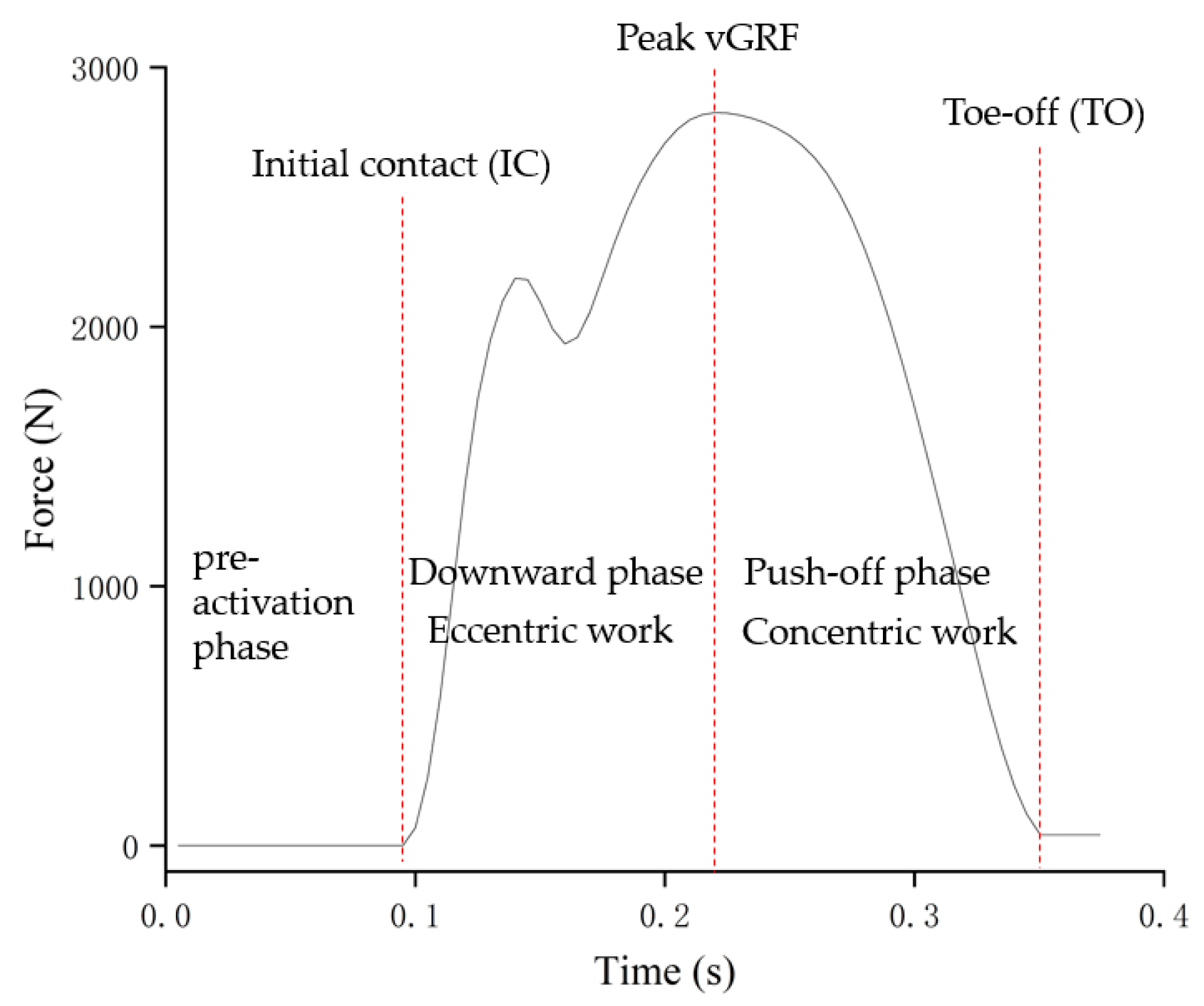

2.3. Surface Electromyography (sEMG) Acquisition and Processing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tai, W.H.; Wang, L.I.; Peng, H.T. Biomechanical Comparisons of One-Legged and Two-Legged Running Vertical Jumps. J. Hum. Kinet. 2018, 64, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabarkapa, D.; Cabarkapa, D.V.; Fry, A.C. Inter-limb asymmetries in professional male basketball and volleyball players: Bilateral vs. unilateral jump comparison. Int. Biomech. 2025, 12, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C. Using the Approach Vertical Jump for Athlete Monitoring and Training. Available online: https://www.sportsmith.co/articles/using-the-approach-vertical-jump-for-athlete-monitoring-and-training/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Allet, L.; Zumstein, F.; Eichelberger, P.; Armand, S.; Punt, I.M. Neuromuscular control mechanisms during single-leg jump landing in subacute ankle sprain patients: A case control study. PM&R 2017, 9, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, P.; Hopkins, W.G.; Andersen, V.; Lindberg, K.; Bjørnsen, T.; Saeterbakken, A.; Paulsen, G. Force-velocity profile based training to improve vertical jump performance a systematic review and meta analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Li, Y.; Lin, G.; Yan, R.; He, J.; Li, D.; Sun, J. Effects of lower limb biomechanical characteristics on jump performance in female volleyball players based on long Stretch–Shortening cycle movements. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1653751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castilla, A.; Rojas, F.J.; Gómez-Martínez, F.; García-Ramos, A. Vertical jump performance is affected by the velocity and depth of the countermovement. Sports Biomech. 2021, 20, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Fan, P.; Wang, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S. The alterations of leg joint angular displacements and muscle co-contraction at landing following various aerial catching movements. J. Men’s Health 2025, 21, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam, A.; Häger, C.K. Thigh muscle co-contraction patterns in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, athletes and controls during a novel double-hop test. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piche, E.; Chorin, F.; Zory, R.; Freitas, P.D.; Guerin, O.; Gerus, P. Metabolic cost and co-contraction during walking at different speeds in young and old adults. Gait Posture 2022, 91, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.K.; Pedley, J.S.; Moeskops, S.; Oliver, J.L.; Myer, G.D.; Hsiao, H.-I.; Lloyd, R.S. Influence of Neuromuscular Training Interventions on Jump-Landing Biomechanics and Implications for ACL Injuries in Youth Females: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 1265–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dami, A.; Payen, E.; Isabelle, P.-L.; Farahpour, N.; Moisan, G. Comparative analysis of lower limb biomechanics during unilateral drop jump landings on even and medially inclined surfaces. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Quan, W.; Ma, X.; Chon, T.-E.; Fernandez, J.; Gusztav, F.; Kovács, A.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. New insights optimize landing strategies to reduce lower limb injury risk. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.M.; Tritsch, A.J.; Cone, J.R.; Schmitz, R.J.; Henson, R.A.; Shultz, S.J. The influence of lower extremity lean mass on landing biomechanics during prolonged exercise. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Quan, W.; Gusztav, F.; Wang, M.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. Accurately and effectively predict the ACL force: Utilizing biomechanical landing pattern before and after-fatigue. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 241, 107761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramoto, Y.; Iwamoto, W.; Iida, S.; Sasagawa, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Ishibuchi, S.; Murakami, J.; Maehara, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Wagatsuma, K. Effectiveness of warm-up and dynamic balance training in preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in college gymnasts: A 3-year prospective study for one team. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2023, 64, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inclan, P.M.; Hicks, J.J.; Retzky, J.S.; Janosky, J.J.; Pearle, A.D. Team Approach: Neuromuscular training for primary and secondary prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injury. JBJS Rev. 2024, 12, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, D.A. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, C.T.; Houdijk, H.H.; Van Strien, C.; Louie, M. Mechanism of leg stiffness adjustment for hopping on surfaces of different stiffnesses. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, P. The ABC of EMG. A Practical Introduction to Kinesiological Electromyography; Noraxon Inc.: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Auriol, P.; Besier, T.; Mcmorland, A.J. Effect of surface electromyography normalisation methods over gait muscle synergies. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2025, 80, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, N.; Scurr, J. Electromyography normalization methods for high-velocity muscle actions: Review and recommendations. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, Y.R.; Bao, S.; Lei, Y. Changes in Motor Unit Activity of Co-activated Muscles During Dynamic Force Field Adaptation. J. Neurophysiol. 2025, 133, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.J.; McBurnie, A.J.; Santos, T.D.; Eriksrud, O.; Evans, M.; Cohen, D.D.; Rhodes, D.; Carling, C.; Kiely, J. Biomechanical and neuromuscular performance requirements of horizontal deceleration: A review with implications for random intermittent multi-directional sports. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 2321–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, H.J.; McIntosh, V.; Leland, A.; Harris-Love, M.O. Progressive resistance exercise with eccentric loading for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Front. Med. 2015, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Lo, W.L.A.; Ding, M.; Wang, C.; Li, L. Upper limbs muscle co-contraction changes correlated with the impairment of the corticospinal tract in stroke survivors: Preliminary evidence from electromyography and motor-evoked potential. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 886909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBurnie, A.J.; Harper, D.J.; Jones, P.A.; Dos’ Santos, T. Deceleration training in team sports: Another potential ‘vaccine’for sports-related injury? Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.R.; Van den Bogert, J.; Myer, G.D.; Shapiro, R.; Hewett, T.E. The effects of age and skill level on knee musculature co-contraction during functional activities: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2008, 42, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Léam, A.; Fouré, A.; Wong, D.P.; Hautier, C.A. Relationship between explosive strength capacity of the knee muscles and deceleration performance in female professional soccer players. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 723041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.F.; Takahashi, K.Z. Gearing up the human ankle-foot system to reduce energy cost of fast walking. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, J.C.; Challis, J.H. Elastic energy within the human plantar aponeurosis contributes to arch shortening during the push-off phase of running. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhong, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, K.; Yuan, H.; Deng, M.; ShangGuan, Y. Position-specific neuromuscular activation and biomechanical characterization of the snap jump in elite male volleyball players: A comparative study of outside and opposite hitters. J. Men’s Health 2025, 21, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Auyang, A.G.; Chang, Y.-H. Effects of a foot placement constraint on use of motor equivalence during human hopping. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centomo, H.; Amarantini, D.; Martin, L.; Prince, F. Differences in the coordination of agonist and antagonist muscle groups in below-knee amputee and able-bodied children during dynamic exercise. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2008, 18, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latash, M.L. Muscle coactivation: Definitions, mechanisms, and functions. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 120, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, S.M.; Diaz, T.O.; Pozzi, F.; Vasilopoulos, T.; Nichols, J.A. Linear relationship between electromyography and shear wave elastography measurements persists in deep muscles of the upper extremity. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2022, 63, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, L.; De Vito, G.; Lowery, M.M. Analysis and biophysics of surface EMG for physiotherapists and kinesiologists: Toward a common language with rehabilitation engineers. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 576729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

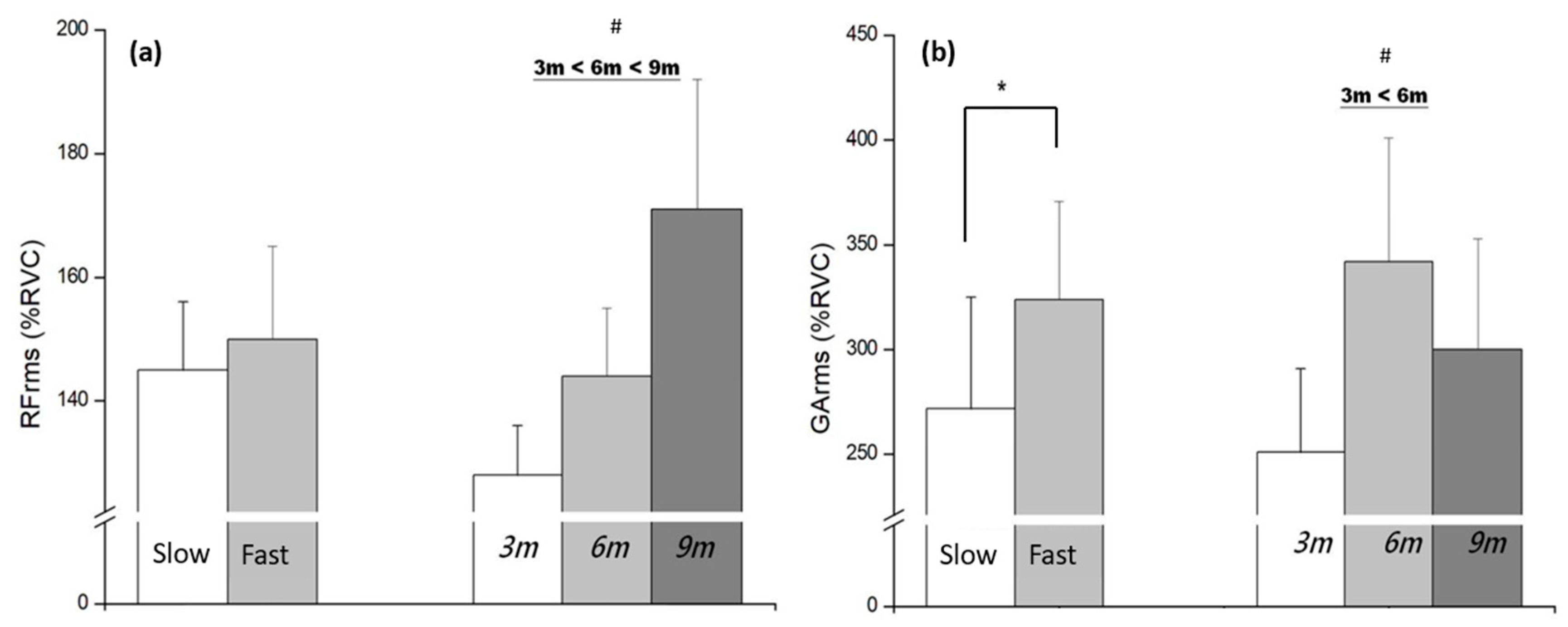

| Variable | Interaction | Speed | 3 m | 6 m | 9 m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF %RVC | p = 0.595 | Slow | 128 ± 8 | 144 ± 11 | 171 ± 21 |

| Fast | 124 ± 10 | 145 ± 15 | 144 ± 25 | ||

| BF %RVC | p = 0.442 | Slow | 145 ± 11 | 153 ± 10 | 149 ± 13 |

| Fast | 142 ± 10 | 136 ± 10 | 155 ± 16 | ||

| TA %RVC | p = 0.002 * | Slow | 165 ± 92 | 277 ± 185 | 280 ± 225 |

| Fast | 226 ± 114 | 304 ± 183 | 423 ± 331 | ||

| GA %RVC | p = 0.469 | Slow | 251 ± 40 | 342 ± 59 | 290 ± 50 |

| Fast | 272 ± 53 | 355 ± 62 | 344 ± 68 | ||

| SOL %RVC | p = 0.476 | Slow | 145 ± 13 | 166 ± 12 | 175 ± 18 |

| Fast | 155 ± 17 | 177 ± 20 | 174 ± 19 | ||

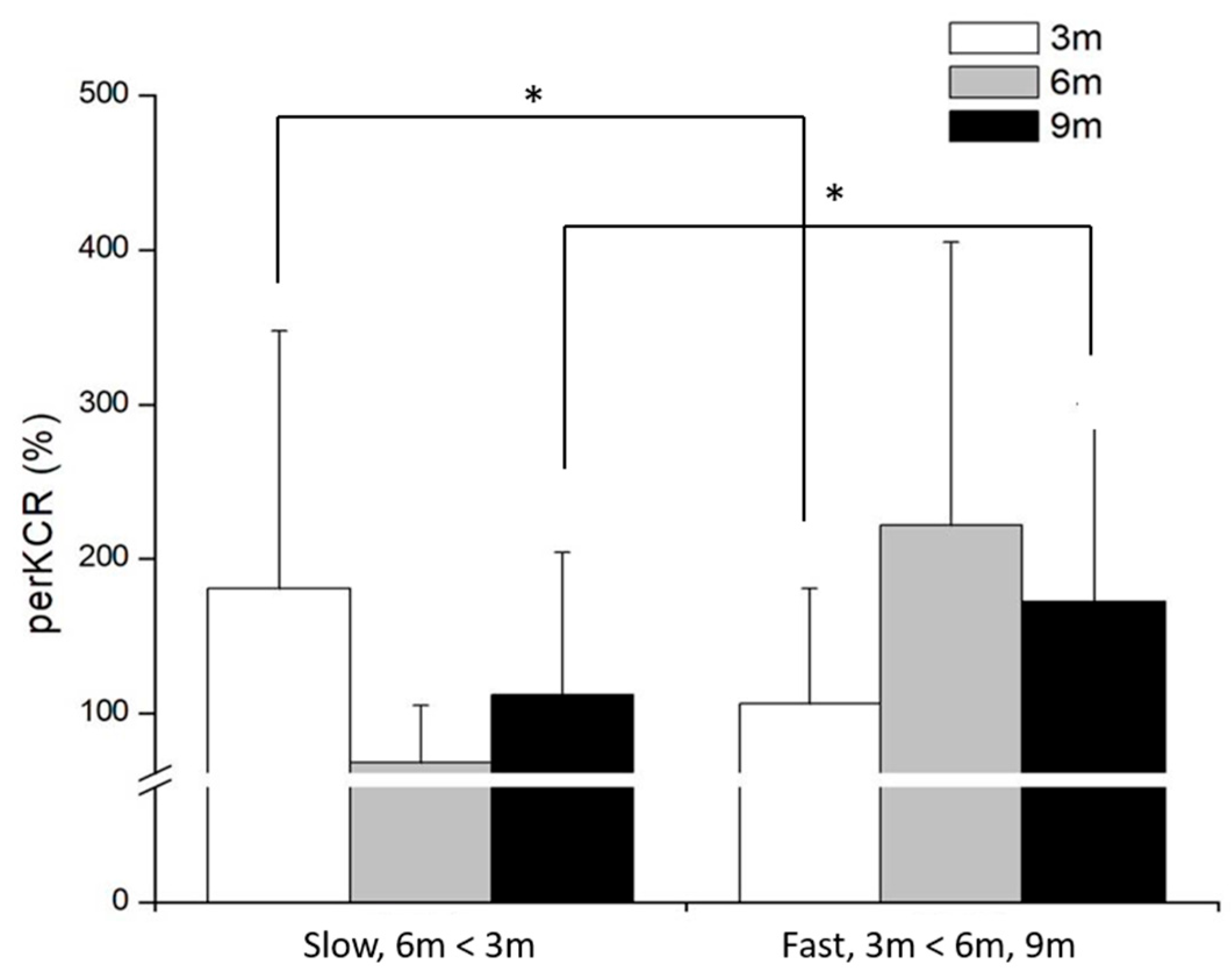

| PreKCR (%) | p = 0.001 * | Slow | 181 ± 167 | 68 ± 37 | 112 ± 92 |

| Fast | 106 ± 75 | 222 ± 183 | 172 ± 119 | ||

| PreACR (%) | p = 0.261 | Slow | 85 ± 88 | 114 ± 126 | 88 ± 84 |

| Fast | 96 ± 106 | 110 ± 103 | 120 ± 145 | ||

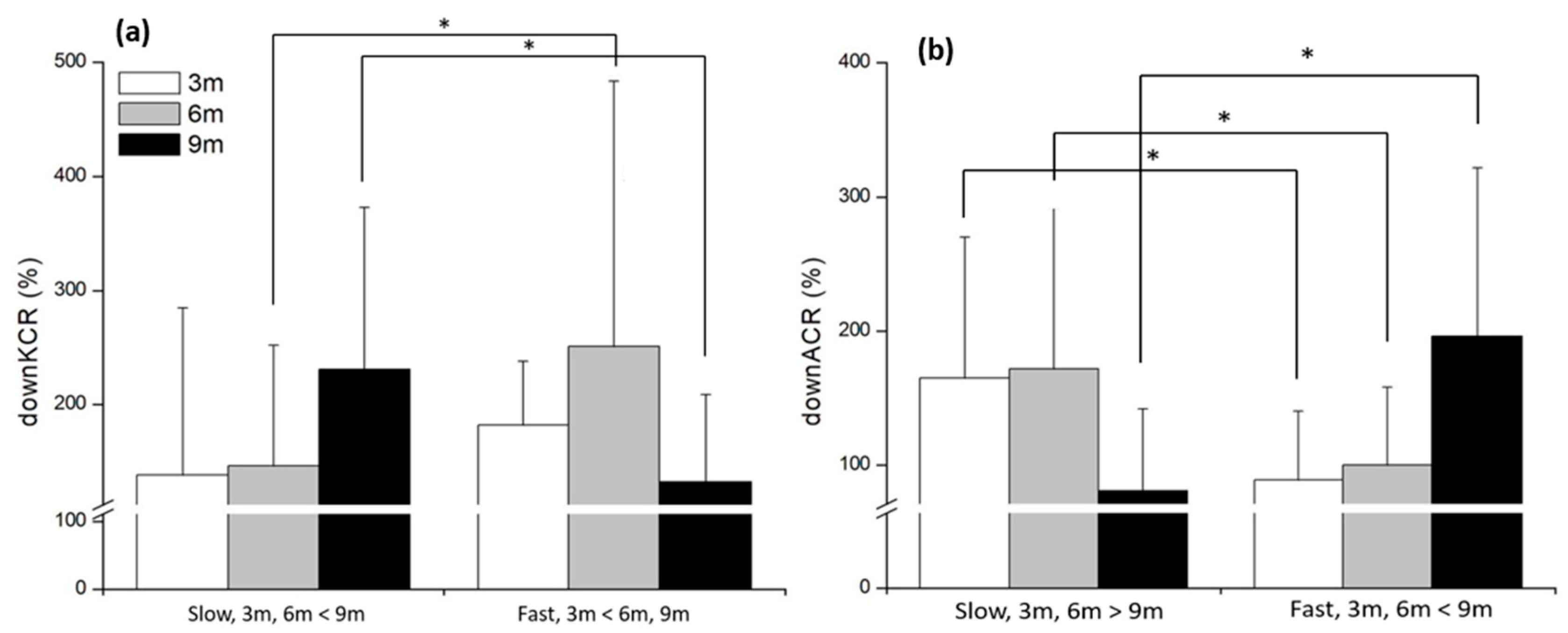

| DownKCR (%) | p < 0.001 * | Slow | 138 ± 147 | 146 ± 106 | 231 ± 142 |

| Fast | 182 ± 56 | 251 ± 232 | 132 ± 77 | ||

| DownACR (%) | p < 0.001 * | Slow | 165 ± 105 | 172 ± 120 | 81 ± 61 |

| Fast | 89 ± 51 | 100 ± 58 | 196 ± 126 | ||

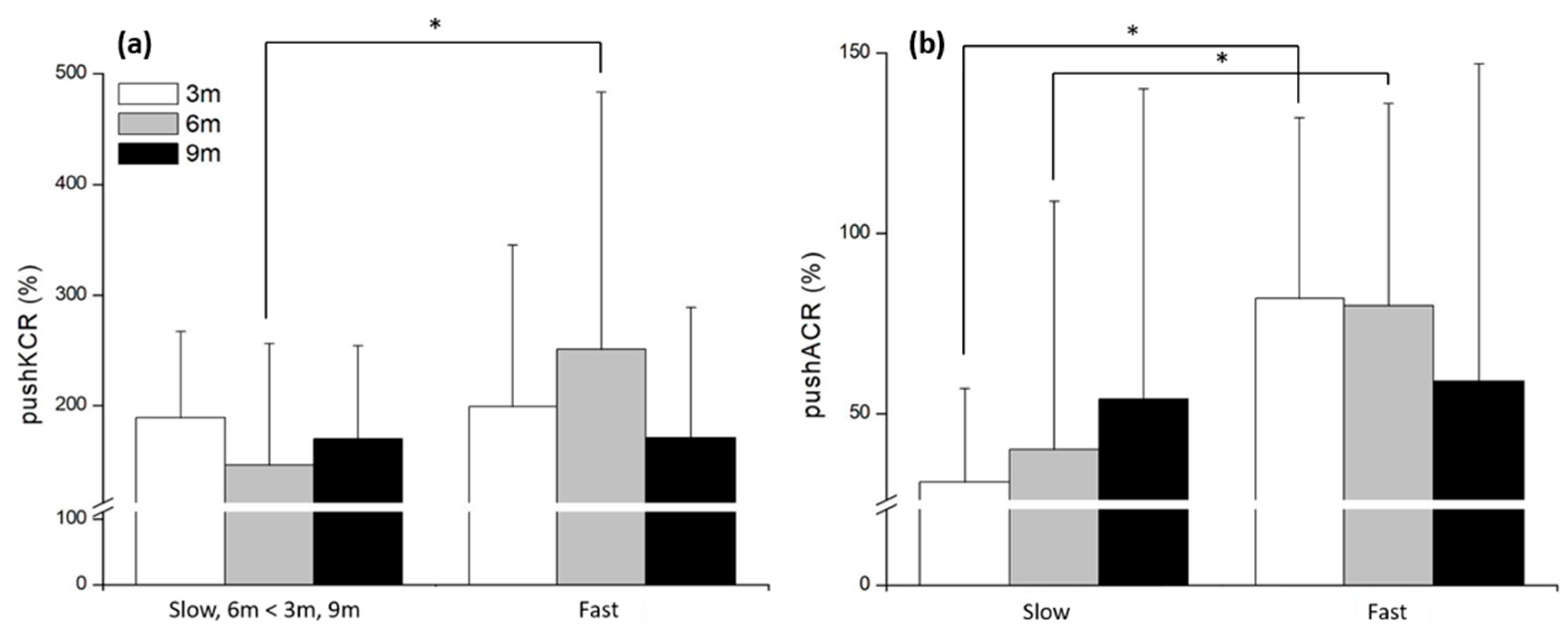

| PushKCR (%) | p = 0.004 * | Slow | 189 ± 78 | 146 ± 110 | 170 ± 84 |

| Fast | 199 ± 146 | 251 ± 232 | 171 ± 118 | ||

| PushACR (%) | p < 0.001 * | Slow | 31 ± 26 | 40 ± 69 | 54 ± 86 |

| Fast | 82 ± 50 | 80 ± 56 | 59 ± 88 |

| Phase | Joint | p (Distance) | p (Velocity) | p (Interaction) | pos hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eccentric | Hip | 0.001 * | 0.342 | 0.12 | 6 m, 9 m > 3 m |

| Knee | 0.362 | 0.073 | 0.289 | ||

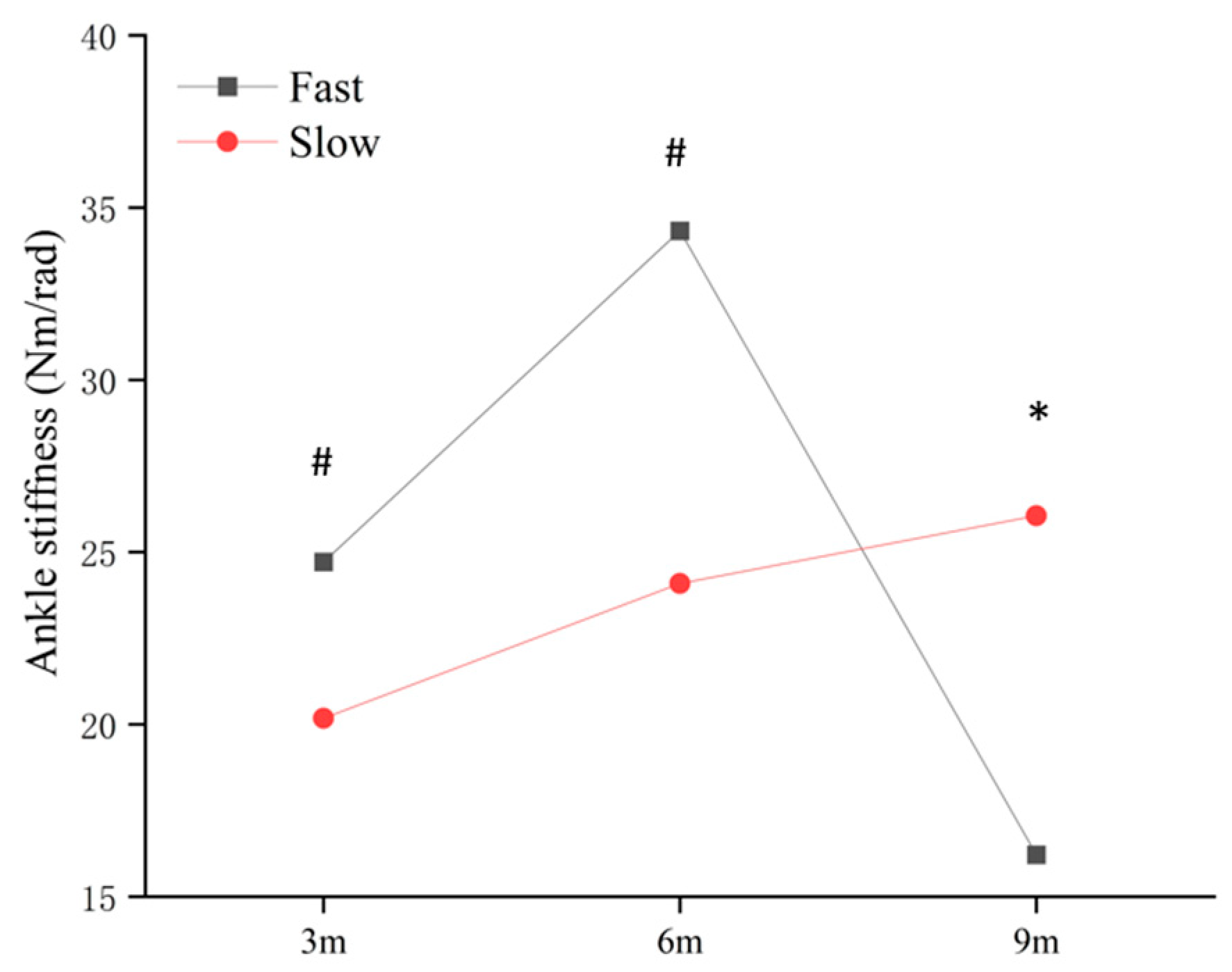

| Ankle | 0.007 * | 0.005 * | 0.003 * | 9F > 9S; 3 m, 6 m > 9 m | |

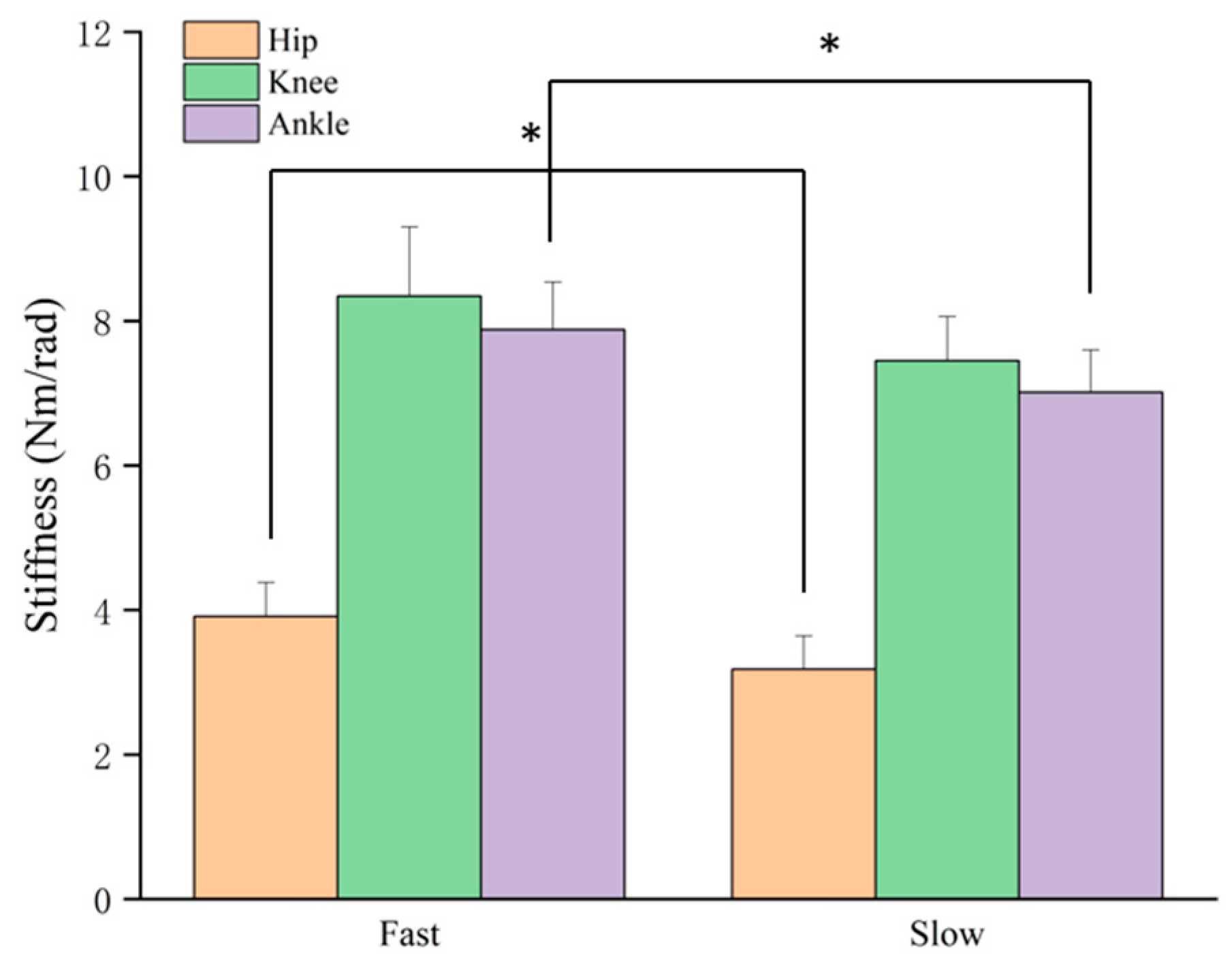

| Concentric | Hip | 0.056 | 0.018 * | 0.333 | F > S |

| Knee | 0.086 | 0.159 | 0.689 | ||

| Ankle | 0.105 | 0.012 * | 0.257 | F > S |

| 3 m | 6 m | 9 m | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joints | Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow |

| Eccentric | ||||||

| Hip | 2.24 ± 1.15 | 2.49 ± 1.02 | 5.77 ± 2.09 | 8.82 ± 4.7 | 7.95 ± 5.68 | 6.27 ± 3.10 |

| Knee | 15.52 ± 6.04 | 12.83 ± 4.59 | 13.63 ± 3.75 | 11.71 ± 2.64 | 14.04 ± 5.59 | 13.18 ± 4.55 |

| Ankle | 24.71 ± 6.13 | 20.18 ± 6.36 | 34.33 ± 16.78 | 24.09 ± 11.03 | 16.22 ± 6.57 | 26.06 ± 8.96 |

| Concentric | ||||||

| Hip | 3.50 ± 1.65 | 2.40 ± 1.79 | 4.08 ± 1.33 | 3.12 ± 1.00 | 4.16 ± 1.79 | 4.02 ± 1.62 |

| Knee | 6.99 ± 1.65 | 6.30 ± 1.46 | 8.90 ± 3.98 | 7.63 ± 1.69 | 9.12 ± 3.39 | 8.43 ± 3.26 |

| Ankle | 7.13 ± 1.58 | 5.61 ± 1.68 | 7.57 ± 1.69 | 7.14 ± 1.63 | 8.92 ± 2.92 | 8.28 ± 3.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tai, W.-H.; Peng, H.-T.; Lin, J.-Z.; Li, P.-A. Adaptive Neuromuscular Co-Contraction Strategies Under Varying Approach Speeds and Distances During Single-Leg Jumping: An Exploratory Study. Life 2025, 15, 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121859

Tai W-H, Peng H-T, Lin J-Z, Li P-A. Adaptive Neuromuscular Co-Contraction Strategies Under Varying Approach Speeds and Distances During Single-Leg Jumping: An Exploratory Study. Life. 2025; 15(12):1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121859

Chicago/Turabian StyleTai, Wei-Hsun, Hsien-Te Peng, Jian-Zhi Lin, and Po-Ang Li. 2025. "Adaptive Neuromuscular Co-Contraction Strategies Under Varying Approach Speeds and Distances During Single-Leg Jumping: An Exploratory Study" Life 15, no. 12: 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121859

APA StyleTai, W.-H., Peng, H.-T., Lin, J.-Z., & Li, P.-A. (2025). Adaptive Neuromuscular Co-Contraction Strategies Under Varying Approach Speeds and Distances During Single-Leg Jumping: An Exploratory Study. Life, 15(12), 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121859