Chitosan Protects Peripheral Nerves Against Damage Induced by Diabetes Mellitus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Laboratory Animals and Maintenance Conditions

2.3. Induction of Diabetes Mellitus and Experimental Allocation

- -

- Sham (DM−): administration of 0.9% NaCl, without STZ; physiological control group.

- -

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus—T1DM (DM+): diabetes induced, without therapeutic intervention.

- -

- T1DM+Chitosan (T1DM+Chitosan): oral administration of chitosan (150 mg/kg/day) by gastric gavage, for 12 weeks.

2.4. Behavioral Assessments

2.4.1. Open Field Test

2.4.2. Mechanical Allodynia Test

2.4.3. Tail-Flick Tail Immersion Test

2.5. Tissue Sampling and Histological Analysis

2.6. Electrophysiological Evaluations

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

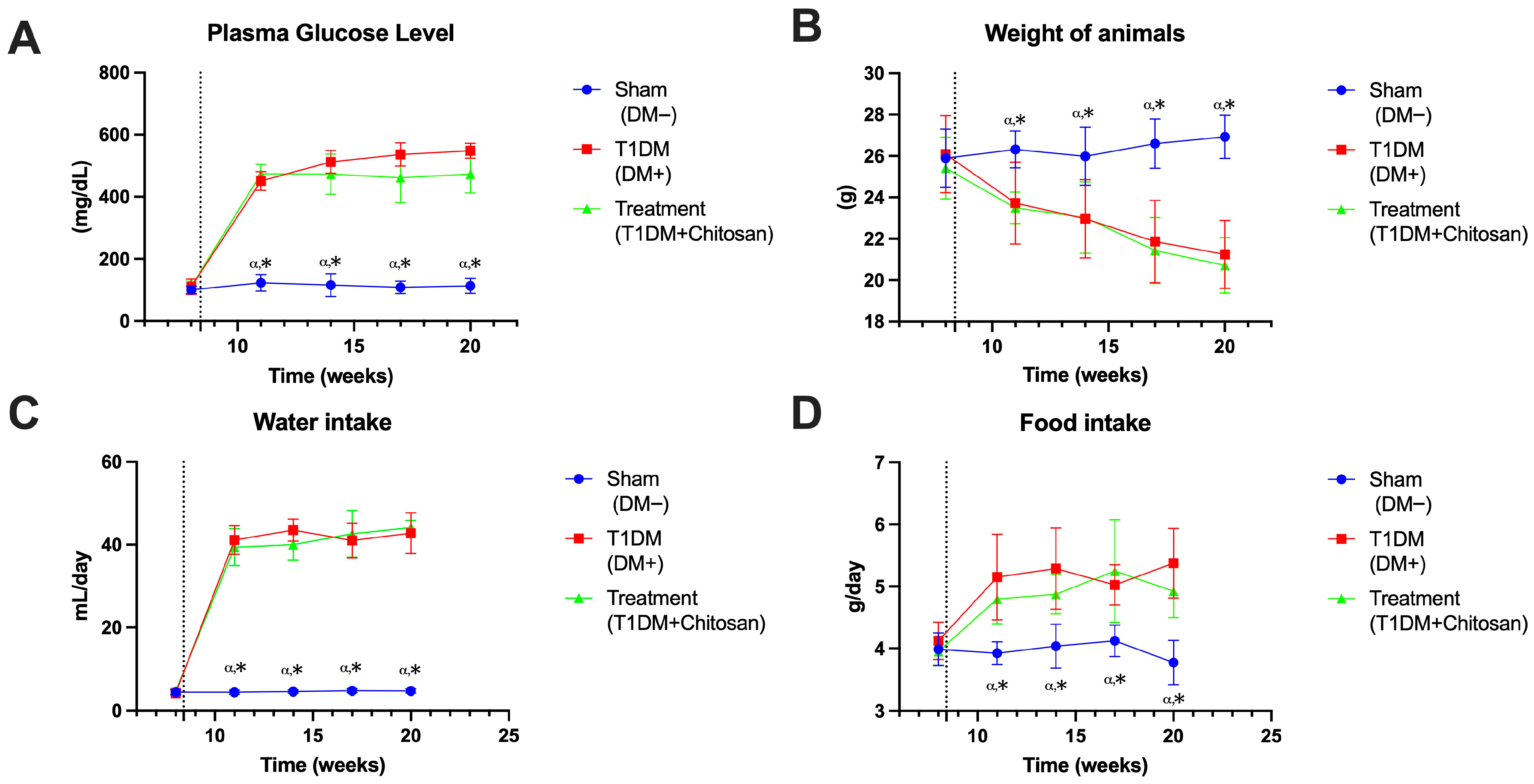

3.1. Assessment of the Impact of Streptozotocin Administration

3.1.1. Plasma Glucose Level

3.1.2. Body Weight

3.1.3. Water Intake

3.1.4. Food Intake

3.2. Effects on Lipid Profile

3.2.1. LDL Cholesterol

3.2.2. HDL Cholesterol

3.2.3. Total Cholesterol

3.2.4. Triglycerides

3.3. Electroneurography

3.4. Behavioral Assessment

3.4.1. Open Field Test

3.4.2. Tail-Flick Tail Immersion Test

3.4.3. Mechanical Allodynia Test

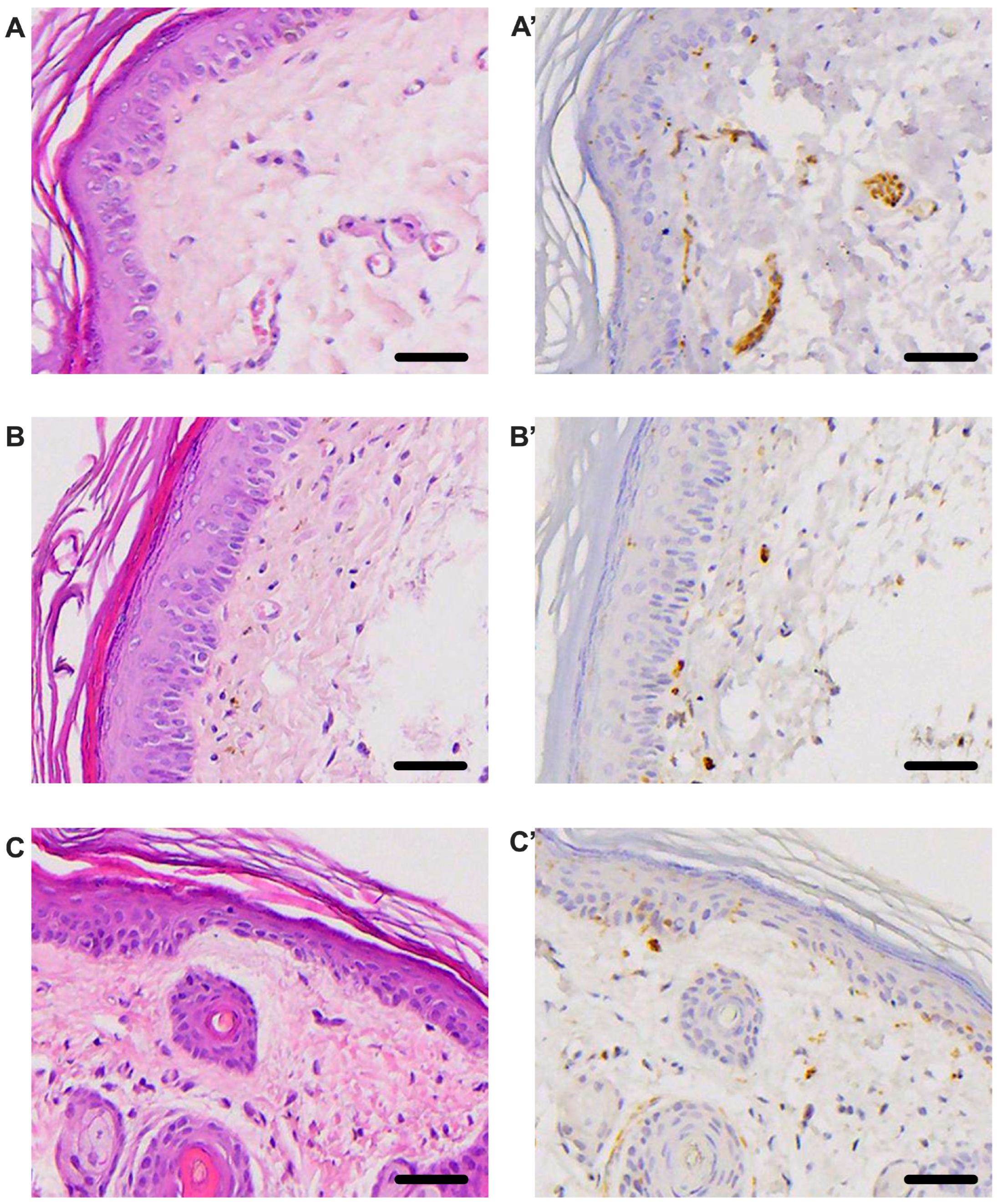

3.5. Histological Evaluation

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rooney, M.R.; He, J.H.; Salpea, P.; Genitsaridi, I.; Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J.; Wallace, A.S.; Fang, M.; Selvin, E. Global and Regional Prediabetes Prevalence: Updates for 2024 and Projections for 2050. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, e142–e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.B.; Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. IDF diabetes atlas 11th edition 2025: Global prevalence and projections for 2050. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2025, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Lu, S.; Zeng, J.; Liu, H. Global, regional, and national trends and burden of diabetes mellitus type 2 among youth from 1990 to 2021: An analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1626225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, M.; Liang, A.; Kan, L.; Cai, Y.; Gong, Q.; Yue, C. The global burden of early-onset type 2 diabetes (1990–2050): An age-period-cohort analysis of incidence, disparities, and projections. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, C.; Ma, J.; Guan, L. The global burden of hearing loss and its comorbidity with chronic diseases: A comprehensive analysis from 1990 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, J.D.; Gronseth, G.S.; Franklin, G.; Miller, R.G.; Asbury, A.K.; Carter, G.T.; Cohen, J.A.; Fisher, M.A.; Howard, J.F.; Kinsella, L.J.; et al. Distal symmetric polyneuropathy: A definition for clinical research: Report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology 2005, 64, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.C.; Yang, S. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy essentials: A narrative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2023, 12, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop-Busui, R.; Boulton, A.J.; Feldman, E.L.; Bril, V.; Freeman, R.; Malik, R.A.; Sosenko, J.M.; Ziegler, D. Diabetic neuropathy: A position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, W.; Du, X.; Luo, Z.; Hu, J.; Peng, S. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: Pathogenetic mechanisms and treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1265372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.W.; Selvin, E. Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy and lower extremity disease in diabetes. Curr. Diab Rep. 2019, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirthi, V.; Perumbalath, A.; Brown, E.; Nevitt, S.; Petropoulos, I.N.; Burgess, J.; Roylance, R.; Cuthbertson, D.J.; Jackson, T.L.; Malik, R.A.; et al. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in pre-diabetes: A systematic review. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e002040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Lan, H.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Cao, P. Diabetic neuropathy: Cutting-edge research and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.N.; Oh, T.J. Pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Metab. J. 2023, 47, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gylfadottir, S.S.; Christensen, D.H.; Nicolaisen, S.K.; Andersen, H.; Callaghan, B.C.; Itani, M.; Khan, K.S.; Kristensen, A.G.; Nielsen, J.S.; Sindrup, S.H.; et al. Diabetic polyneuropathy and pain, prevalence, and patient characteristics: A cross-sectional questionnaire study of 5,514 patients with recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Pain 2020, 161, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolano, M.; Tozza, S.; Caporaso, G.; Provitera, V. Contribution of skin biopsy in peripheral neuropathies. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltier, A.C.; Myers, M.I.; Artibee, K.J.; Hamilton, A.D.; Yan, Q.; Guo, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Evaluation of dermal myelinated nerve fibers in diabetes mellitus. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2013, 18, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillo, P.; Yiangou, Y.; Donatien, P.; Greig, M.; Selvarajah, D.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Anand, P.; Tesfaye, S. Nerve and vascular biomarkers in skin biopsies differentiate painful from painless peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Front. Pain Res. 2021, 2, 731658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, G. Serum C-Reactive Protein to Albumin Ratio as a Reliable Marker of Diabetic Neuropathy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomol. Biomed. 2024, 24, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan, G.; Vejux, A.; Sahakyan, N. The Role of Oxidative Stress-Mediated Inflammation in the Development of T2DM-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy: Possible Preventive Action of Tannins and Other Oligomeric Polyphenols. Molecules 2022, 27, 9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicea, D.; Nicolae-Maranciuc, A. A review of chitosan-based materials for biomedical, food, and water treatment applications. Materials 2024, 17, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, M.; Lewandowska, K. Biomaterials based on chitosan and its derivatives and their potential in tissue engineering and other biomedical applications—A review. Molecules 2022, 28, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonciarz, W.; Balcerczak, E.; Brzeziński, M.; Jeleń, A.; Pietrzyk-Brzezińska, A.J.; Narayanan, V.H.B.; Chmiela, M. Chitosan-based formulations for therapeutic applications: A recent overview. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Târtea, G.; Popa-Wagner, A.; Sfredel, V.; Mitran, S.I.; Dan, A.O.; Țucă, A.M.; Preda, A.N.; Raicea, V.; Țieranu, E.; Cozma, D.; et al. Chitosan versus dapagliflozin in a diabetic cardiomyopathy mouse model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardani, G.; Nugraha, J.; Mustafa, M.R.; Kurnijasanti, R.; Sudjarwo, S.A. Antioxidative Stress and Antiapoptosis Effect of Chitosan Nanoparticles to Protect Cardiac Cell Damage on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rat. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3081397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.Y.; Jang, M.K.; Nah, J.W. Influence of molecular weight on oral absorption of water soluble chitosans. J. Control. Release 2005, 102, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Qin, C.; Wang, W.; Chi, W.; Li, W. Absorption and distribution of chitosan in mice after oral administration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 71, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Chang, Y.H.; Chiang, M.T. Chitosan reduces gluconeogenesis and increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5795–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, H.P.; Liu, S.H.; Chiang, M.T. Antidiabetic properties of chitosan and its derivatives. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Chen, R.Y.; Chiang, M.T. Effects and mechanisms of chitosan and chitosan oligosaccharide on hepatic lipogenesis and lipid peroxidation, adipose lipolysis, and intestinal lipid absorption in rats with high-fat diet-induced obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Wang, G.; Wei, J. The role of chitosan oligosaccharide in metabolic syndrome: A review of possible mechanisms. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 3617–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoiu, I.; Târtea, G.; Sfredel, V.; Raicea, V.; Țucă, A.M.; Preda, A.N.; Cozma, D.; Vătășescu, R. Dapagliflozin ameliorates neural damage in the heart and kidney of diabetic mice. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Park, Y.S.; Choi, J.W.; Yi, S.Y.; Shin, W.S. Antidiabetic effects of chitosan oligosaccharides in neonatal streptozotocin-induced noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ding, Q.; He, Q.; Zu, T.; Rong, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shmanai, V.V.; Jiao, J.; Zheng, R. Renoprotective potential of taxifolin liposomes modified by chitosan in diabetic mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthick, V.; Zahir, A.A.; Amalraj, S.; Rahuman, A.A.; Anbarasan, K.; Santhoshkumar, T. Sustained release of nano-encapsulated glimepiride drug with chitosan nanoparticles: A novel approach to control type 2 diabetes in streptozotocin-induced Wistar albino rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 287, 138496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.-I.; Cho, S.; Choi, N.-J. Effectiveness of Chitosan as a Dietary Supplement in Lowering Cholesterol in Murine Models: A Meta-Analysis. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.C.; Qi, Z.; Wu, C.C.; Shirouza, Y.; Lin, F.H.; Yanai, G.; Sumi, S. The cytoprotection of chitosan based hydrogels in xenogeneic islet transplantation: An in vivo study in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.N.; Chang, I.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Park, K.S.; Kim, H.I.; Yoon, S.P. The role of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease on the progression of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats. Acta Histochem. 2012, 114, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abozaid, O.A.R.; El-Sonbaty, S.M.; Hamam, N.M.A.; Farrag, M.A.; Kodous, A.S. Chitosan-encapsulated nano-selenium targeting TCF7L2, PPARγ, and CAPN10 genes in diabetic rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandireddy, R.; Yerra, V.G.; Areti, A.; Komirishetty, P.; Kumar, A. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic neuropathy: Futuristic strategies based on these targets. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 674987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, E.L. Oxidative stress and diabetic neuropathy: A new understanding of an old problem. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M. Recent advances in understanding the role of oxidative stress in diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2015, 9, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M.; Constantin, C.; Surcel, M.; Munteanu, A.; Scheau, C.; Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Caruntu, C. Diabetic neuropathy: A NRF2 disease? J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e13524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, G.; Kumar, A.; Joshi, R.P.; Sharma, S.S. Oxidative stress and Nrf2 in the pathophysiology of diabetic neuropathy: Old perspective with a new angle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 408, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Lin, Q.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Deng, B. Anti-inflammatory effect of resveratrol attenuates the severity of diabetic neuropathy by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Aging 2021, 13, 10659–10671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotphruethipong, L.; Chanvorachote, P.; Reudhabibadh, R.; Singh, A.; Benjakul, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Hutamekalin, P. Chitooligosaccharide from Pacific white shrimp shell chitosan ameliorates inflammation and oxidative stress via NF-κB, Erk1/2, Akt and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Foods 2023, 12, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyung, J.H.; Ahn, C.B.; Il Kim, B.; Kim, K.; Je, J.Y. Involvement of Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 expression in anti-inflammatory action of chitosan oligosaccharides through MAPK activation in murine macrophages. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 793, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, E.; Ebedy, Y.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Farroh, K.Y.; Hassanen, E.I. Newly synthesized chitosan-nanoparticles attenuate carbendazim hepatorenal toxicity in rats via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathway. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanen, E.I.; Ebedy, Y.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Farroh, K.Y.; Elshazly, M.O. Insights overview on the possible protective effect of chitosan nanoparticles encapsulation against neurotoxicity induced by carbendazim in rats. Neurotoxicology 2022, 91, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, R.; Kim, S.K. Neuroprotective properties of chitosan and its derivatives. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, T.; Tian, K.; Li, Z.; Luo, F. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging biomaterials for anti-inflammatory diseases: From mechanism to therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecker, A.; Daeschler, S.C.; Kneser, U.; Harhaus, L. Relevance and recent developments of chitosan in peripheral nerve surgery. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; An, H.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, H.; Wan, T.; Wen, Y.; Han, N.; Zhang, P. Prospects of using chitosan-based biopolymers in the treatment of peripheral nerve injuries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, C.; Ong, E.; Emovon, E.O.; Shafique, H.; Valenta, M.A.F.; Mohite, A.S.; Li, N.Y. Utility of chitosan-based devices in the treatment of peripheral nerve injuries: A literature review. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, R.; Sanaei, N.; Ahsan, S.; Rostami, H.; Abbasipour-Dalivand, S.; Amini, K. Repair of nerve defect with chitosan graft supplemented by uncultured characterized stromal vascular fraction in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haastert-Talini, K.; Dahlin, L.B. Diabetes, its impact on peripheral nerve regeneration: Lessons from pre-clinical rat models towards nerve repair and reconstruction. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, G.L.; Ray, M.; Burcus, N.I.; McNulty, P.; Basta, B.; Vinik, A.I. Intraepidermal nerve fibers are indicators of small-fiber neuropathy in both diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1974–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timar, B.; Popescu, S.; Timar, R.; Baderca, F.; Duica, B.; Vlad, M.; Levai, C.; Balinisteanu, B.; Simu, M. The usefulness of quantifying intraepidermal nerve fibers density in the diagnostic of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A cross-sectional study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2016, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.; Kendig, M.D.; Letton, M.E.; Morris, M.J.; Arnold, R. Peripheral neuropathy phenotyping in rat models of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Evaluating uptake of the Neurodiab guidelines and identifying future directions. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Li, X.; Tian, H.; Liu, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Neuroprotective effect of diosgenin in a mouse model of diabetic peripheral neuropathy involves the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, A.B.; Mohsen, A.M.; ElShebiney, S.; Elgohary, R.; Younis, M.M. Development of chitosan lipid nanoparticles to alleviate the pharmacological activity of piperine in the management of cognitive deficit in diabetic rats. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Țucă, A.-M.; Albu, C.; Preda, A.N.; Dan, A.O.; Târtea, E.-A.; Greșiță, A.; Pîrșcoveanu, D.F.V.; Sfredel, V.; Mitran, S.I.; Târtea, G. Chitosan Protects Peripheral Nerves Against Damage Induced by Diabetes Mellitus. Life 2025, 15, 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121860

Țucă A-M, Albu C, Preda AN, Dan AO, Târtea E-A, Greșiță A, Pîrșcoveanu DFV, Sfredel V, Mitran SI, Târtea G. Chitosan Protects Peripheral Nerves Against Damage Induced by Diabetes Mellitus. Life. 2025; 15(12):1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121860

Chicago/Turabian StyleȚucă, Anca-Maria, Carmen Albu, Alexandra Nicoleta Preda, Alexandra Oltea Dan, Elena-Anca Târtea, Andrei Greșiță, Denisa Floriana Vasilica Pîrșcoveanu, Veronica Sfredel, Smaranda Ioana Mitran, and Georgică Târtea. 2025. "Chitosan Protects Peripheral Nerves Against Damage Induced by Diabetes Mellitus" Life 15, no. 12: 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121860

APA StyleȚucă, A.-M., Albu, C., Preda, A. N., Dan, A. O., Târtea, E.-A., Greșiță, A., Pîrșcoveanu, D. F. V., Sfredel, V., Mitran, S. I., & Târtea, G. (2025). Chitosan Protects Peripheral Nerves Against Damage Induced by Diabetes Mellitus. Life, 15(12), 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121860