Immature Platelet Fraction as a Surrogate Marker of Thrombo-Inflammation in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

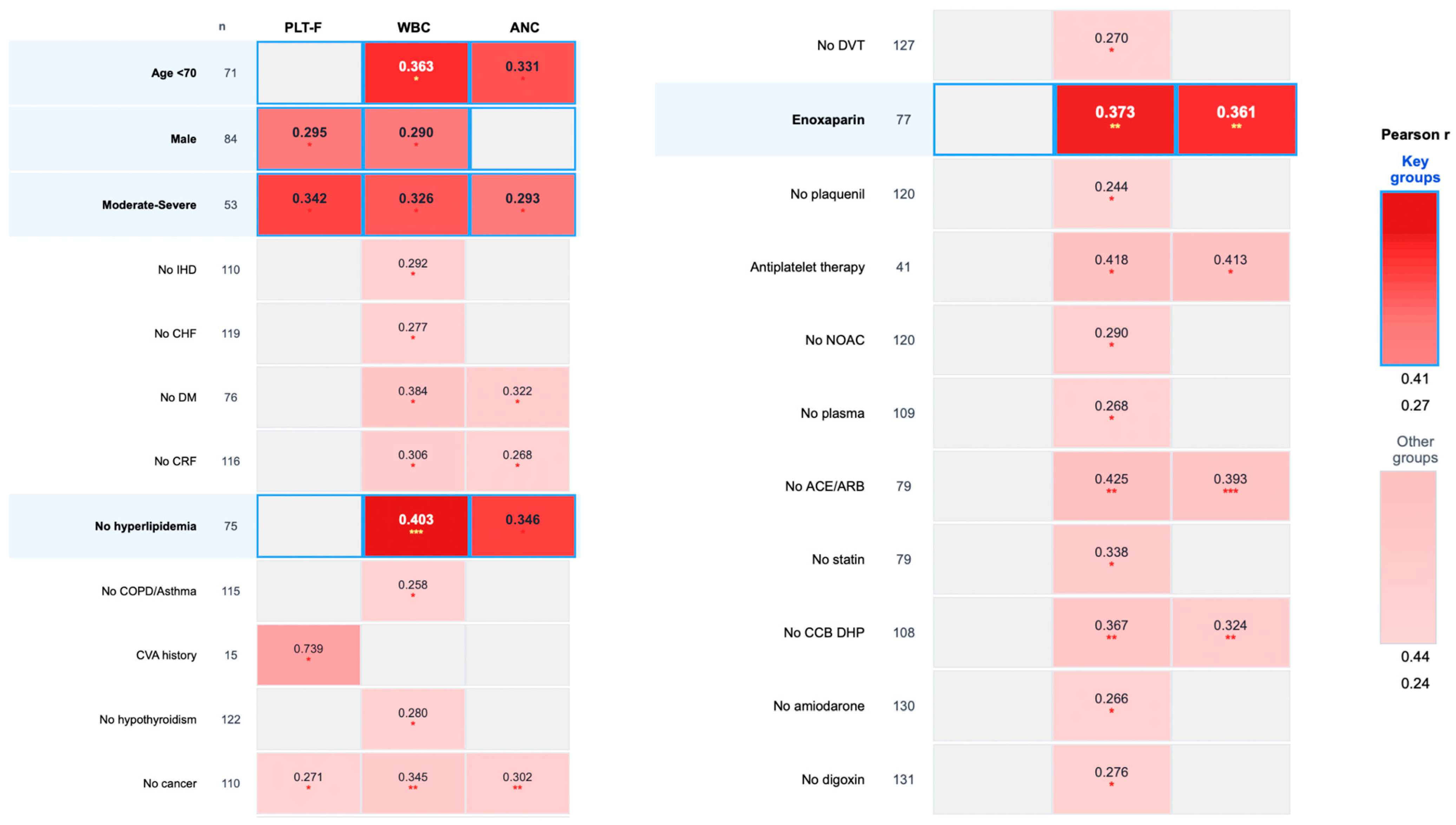

- Age < 70 years (n = 71): IPF vs. WBC (r = 0.363, p = 0.026) and ANC (r = 0.331, p = 0.033).

- Male patients (n = 84): IPF vs. WBC (r = 0.290, p = 0.046) and PLT-F (r = 0.295, p = 0.046).

- Moderate-to-severe disease (n = 53): IPF vs. PLT-F (r = 0.342, p = 0.026), WBC (r = 0.326, p = 0.026), and ANC (r = 0.293, p = 0.039).

- Patients without hyperlipidemia (n = 75): IPF vs. WBC (r = 0.403, p = 0.0004) and ANC (r = 0.346, p = 0.013).

- Patients requiring enoxaparin (n = 77): IPF vs. WBC (r = 0.373, p = 0.007) and ANC (r = 0.361, p = 0.007); see Figure 1.

3.2. Comorbidities

3.3. Treatment-Related Associations

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPF | Immature platelet fraction |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| PLR | Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Asparatate aminotransferase |

| RP | Reticulated platelets |

References

- Umakanthan, S.; Sahu, P.; Ranade, A.V.; Bukelo, M.M.; Rao, J.S.; Abrahao-Machado, L.F.; Daha, l.S.; Kumar, H.; Kv, D. Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 96, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponti, G.; Maccaferri, M.; Ruini, C.; Tomasi, A.; Ozben, T. Biomarkers associated with COVID-19 disease progression. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2020, 57, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, M.; Dittrich, M.; Knabbe, C.; Birschmann, I. Immature platelets in COVID-19. Platelets 2023, 34, 2184183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, R.; Walker, V.; Ip, S.; Cooper, J.A.; Bolton, T.; Keene, S.; Denholm, R.; Akbari, A.; Abbasizanjani, H.; Torabi, F.; et al. CVD-COVID-UK/COVID-IMPACT Consortium and the Longitudinal Health and Wellbeing COVID-19 National Core Study. Association of COVID-19 With Major Arterial and Venous Thrombotic Diseases: A Population-Wide Cohort Study of 48 Million Adults in England and Wales. Circulation 2022, 146, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Harari, E.; Cipok, M.; Laish-Farkash, A.; Bryk, G.; Yahud, E.; Sela, Y.; Lador, N.K.; Mann, T.; Mayo, A.; et al. Immature platelets in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 51, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Harari, E.; Yahud, E.; Cipok, M.; Bryk, G.; Lador, N.K.; Mann, T.; Mayo, A.; Lev, E.I. Immature platelets in patients with COVID-19: Association with disease severity. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 52, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, L.; Lenz, M.; Vlachos, A.; Grüning, B.; Hein, L.; Neumann, F.J.; Nührenberg, T.G.; Trenk, D. Ultrastructural, transcriptional, and functional differences between human reticulated and non-reticulated platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2034–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, F.; Marcucci, R.; Gori, A.M.; Caporale, R.; Fanelli, A.; Casola, G.; Balzi, D.; Barchielli, A.; Valente, S.; Giglioli, C.; et al. Reticulated platelets predict cardiovascular death in acute coronary syndrome patients. Insights from the AMI-Florence 2 Study. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 109, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, H.; Schutt, R.C.; Hannawi, B.; DeLao, T.; Barker, C.M.; Kleiman, N.S. Association of immature platelets with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benlachgar, N.; Doghmi, K.; Masrar, A.; Mahtat, E.M.; Harmouche, H.; Tazi Mezalek, Z. Immature platelets: A review of the available evidence. Thromb. Res. 2020, 195, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, E.L.; Hvas, A.M.; Kristensen, S.D. Immature platelets in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 101, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takami, A.; Shibayama, M.; Orito, M.; Omote, M.; Okumura, H.; Yamashita, T.; Shimadoi, S.; Yoshida, T.; Nakao, S.; Asakura, H. Immature platelet fraction for prediction of platelet engraftment after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007, 39, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enz Hubert, R.M.; Rodrigues, M.V.; Andreguetto, B.D.; Santos, T.M.; de Fátima Pereira Gilberti, M.; de Castro, V.; Annichino-Bizzacchi, J.M.; Dragosavac, D.; Carvalho-Filho, M.A.; De Paula, E.V. Association of the immature platelet fraction with sepsis diagnosis and severity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Blasi, R.A.; Cardelli, P.; Costante, A.; Sandri, M.; Mercieri, M.; Arcioni, R. Immature platelet fraction in predicting sepsis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muronoi, T.; Koyama, K.; Nunomiya, S.; Lefor, A.K.; Wada, M.; Koinuma, T.; Shima, J.; Suzukawa, M. Immature platelet fraction predicts coagulopathy-related platelet consumption and mortality in patients with sepsis. Thromb. Res. 2016, 144, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treatment Guidelines [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health (US), 21 April 2021–29 February 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570371/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK570371.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Jose, R.J.; Manuel, A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: The interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, e46–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte-Schrepping, J.; Reusch, N.; Paclik, D.; Baßler, K.; Schlickeiser, S.; Zhang, B.; Krämer, B.; Krammer, T.; Brumhard, S.; Bonaguro, L.; et al. Severe COVID-19 is Marked by a Dysregulated Myeloid Cell Compartment. Cell 2020, 182, 1419–1440.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alisik, M.; Erdogan, U.G.; Ates, M. Predictive value of immature granulocyte count and other inflammatory parameters for disease severity in COVID-19 patients. Intl. J. Med. Biochem. 2021, 4, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Geng, N.; Pan, W.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, H.; Song, Q.; Liu, B.; Ma, Y. Study on the predictive value of laboratory inflammatory markers and blood count-derived inflammatory markers for disease severity and prognosis in COVID-19 patients: A study conducted at a university-affiliated infectious disease hospital. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2415401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Wu, X.; Jing, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Novakovic, V.A.; Shi, J. The impact of platelets on pulmonary microcirculation throughout COVID-19 and its persistent activating factors. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 955654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carobbio, A.; Ferrari, A.; Masciulli, A.; Ghirardi, A.; Barosi, G.; Barbui, T. Leukocytosis and thrombosis in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Wolf, D.; Sormann, S.; Forjan, E.; Schimetta, W.; Gisslinger, B.; Heibl, S.; Krauth, M.T.; Thiele, J.; Ruckser, R.; et al. Impact of platelets on major thrombosis in patients with a normal white blood cell count in essential thrombocythemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2021, 106, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolfi, R.; Di Gennaro, L. Pathophysiology of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica 2011, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Wu, Y.Y.; Lip, G.Y.; Yin, P.; Hu, Y. Heart failure and risk of venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders. Nature 2017, 542, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniangi-Muhitu, H.; Akalestou, E.; Salem, V.; Misra, S.; Oliver, N.S.; Rutter, G.A. COVID-19 and Diabetes: A Complex Bidirectional Relationship. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 582936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, B.K.; Denorme, F.; Middleton, E.A.; Portier, I.; Rowley, J.W.; Stubben, C.; Petrey, A.C.; Tolley, N.D.; Guo, L.; Cody, M.; et al. Platelet gene expression and function in patients with COVID-19. Blood 2020, 136, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumiężna, K.; Baruś, P.; Sygitowicz, G.; Wiśniewska, A.; Ochijewicz, D.; Pasierb, K.; Klimczak-Tomaniak, D.; Kuca-Warnawin, E.; Kochman, J.; Grabowski, M.; et al. Immature platelet fraction in cardiovascular diagnostics and antiplatelet therapy monitoring. Cardiol. J. 2023, 30, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic and Clinical Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 68 (19–101) |

| >70, n (%) | 62 (47) |

| <70, n (%) | 71 (53) |

| Weight (kg), median (range) | 83.5 (50–130) |

| Sex, n (%) | 133 (100) |

| Male | 84 (63) |

| Female | 49 (37) |

| Disease degree, n (%) | 131 (100) |

| Mild | 53 (40.5) |

| Moderate to severe | 78 (59.5) |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 13 (90) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 23 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 57 (43%) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 58 (43.5%) |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 17 (13%) |

| COPD or Asthma, n (%) | 18 (13.5%) |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 14 (10.5) |

| History of cerebrovascular accident, n (%) | 15 (11) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 19 (14) |

| Solid cancer or lymphoma, n (%) | 23 (17) |

| Deep vein thrombosis, n (%) | 6 (4.5) |

| Laboratory findings | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), median (IQR) | 60 (0.3–374.5) |

| White blood cells (*103/µL), median (IQR) | 7.5 (1.6–22) |

| Absolute neutrophil count (*103/µL), median (IQR) | 5.8 (0.9–19.6) |

| Lymphocytes (*103/µL), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.1–4.1) |

| Fluorescence platelet count (PLT-F) (*103/µL), median (IQR) | 224 (78–762) |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, median (IQR) | 6.4 (0.76–74) |

| Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, median (IQR) | 241.6 (64.4–1996.66) |

| D-dimer (mg/L), median (IQR) | 0.93 (0.9–34.24) |

| Ferritin (ug/L), median (IQR) | 675 (12–11870) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 508 (90–900) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L), median (IQR) | 550 (248–1484) |

| ALT (U/L), median (IQR) | 29 (8–414) |

| AST (U/L), median (IQR) | 34 (11–332) |

| Subgroup | n | PLT-F | WBC | ANC | LDH | Fibrinogen | D-Dimer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 70 | 71 | N/A | r 1 = 0.363 p 2 = 0.026 | r = 0.331 p = 0.033 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Male | 84 | r = 0.295 p = 0.046 | r = 0.290 p = 0.046 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Disease degree 2/3 | 53 | r = 0.342 p = 0.026 | r = 0.326 p = 0.026 | r = 0.293 p = 0.039 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No ischemic heart disease | 110 | N/A | r = 0.292 p = 0.026 | r = 0.25 p = 0.052 n req. 3 = 123 | r = 0.241 p = 0.052 n req. = 133 | N/A | N/A |

| No congestive heart failure | 119 | r = 0.233 p = 0.048 | r = 0.277 p = 0.026 | r = 0.236 p = 0.048 | r = 0.211 p = 0.081 n req. = 174 | N/A | N/A |

| Congestive heart failure | 14 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | r = 0.785 p = 0.013 |

| No diabetes mellitus | 76 | r = 0.271 p = 0.059 n req. = 105 | r = 0.384 p = 0.013 | r = 0.322 p = 0.033 | r = 0.312 p = 0.035 | N/A | N/A |

| No chronic renal failure | 116 | r = 0.212 p = 0.072 n req. = 172 | r = 0.306 p = 0.013 | r = 0.268 p = 0.026 | r = 0.233 p = 0.061 n req. = 142 | N/A | N/A |

| No hyperlipidemia | 75 | N/A | r = 0.403 p = 0.0004 | r = 0.346 p = 0.013 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No COPD or asthma | 115 | r = 0.249 p = 0.046 | r = 0.258 p = 0.046 | r = 0.228 p = 0.061 n req. = 149 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 15 | r = 0.739 p = 0.026 | r = 0.618 p = 0.061 n req.= 18 | r = 0.633 p = 0.061 n req. = 17 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No hypothyroidism | 122 | r = 0.204 p = 0.078 n req. = 186 | r = 0.28 p = 0.026 | r = 0.242 p = 0.046 | r = 0.219 p = 0.078 n req. = 161 | N/A | N/A |

| No solid cancer or lymphoma | 110 | r = 0.271 p = 0.013 | r = 0.345 p = 0.00026 | r = 0.302 p = 0.007 | r = 0.218 p = 0.068 n req. = 163 | r = 0.361 p = 0.009 | N/A |

| No deep vein thrombosis | 127 | r = 0.223 p = 0.052 n req. = 156 | r = 0.270 p = 0.026 | r = 0.230 p = 0.052 n req. = 146 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Enoxaparin | 77 | N/A | r = 0.373 p = 0.007 | r = 0.361 p = 0.007 | r = 0.269 p = 0.078 n req. = 106 | N/A | N/A |

| No plaquenil | 120 | r = 0.243 p = 0.046 | r = 0.244 p = 0.046 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Plaquenil | 13 | N/A | N/A | N/A | r = 0.843 p = 0.013 | N/A | N/A |

| With antiplatelet therapy | 41 | r = 0.377 p = 0.065 n req = 53 | r = 0.418 p = 0.046 | r = 0.413 p = 0.046 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No NOAC | 120 | r = 0.251 p = 0.026 | r = 0.290 p = 0.013 | r = 0.251 n = 0.026 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No plasma from past COVID | 109 | r = 0.262 p = 0.039 | r = 0.268 p = 0.039 | r = 0.226 p = 0.078 n req. = 183 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No ACE/ARB | 79 | r = 0.264 p = 0.062 n req. = 110 | r = 0.425 p = 0.001 | r = 0.393 p = 0.0004 | r = 0.374 p = 0.004 | N/A | N/A |

| No statin | 79 | N/A | r = 0.338 p = 0.026 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No CCB DHP | 108 | r = 0.263 p = 0.026 | r = 0.367 p = 0.001 | r = 0.324 p = 0.007 | r = 0.248 p = 0.039 | N/A | N/A |

| No amiodarone | 130 | r = 0.237 p = 0.035 | r = 0.266 p = 0.026 | r = 0.231 p = 0.035 | r = 0.203 p = 0.078 n req. = 188 | N/A | N/A |

| No digoxin | 131 | r = 0.223 p = 0.048 | r = 0.276 p = 0.013 | r = 0.243 p = 0.033 | r = 0.206 p = 0.068 n req. = 183 | N/A | N/A |

| Subgroup | n | IPF (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Range | ||

| Total cohort | 133 | 1.9 (0.2–25) | 0.1–29 |

| Age < 70 years | 71 | 2.5 (0.5–27) | 0.1–29 |

| Male | 84 | 2.3 (0.3–26) | 0.1–29 |

| Moderate-to-severe disease | 78 | 2.7 (0.8–28) | 0.1–29 |

| Enoxaparin required | 77 | 2.6 (0.6–27) | 0.1–29 |

| Congestive heart failure | 14 | 3.5 (1.1–29) | 0.4–29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duek, A.; Zimin, A.; Hershkop, Y.; Cipok, M.; Cohen, A.; Leiba, M. Immature Platelet Fraction as a Surrogate Marker of Thrombo-Inflammation in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Life 2025, 15, 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121846

Duek A, Zimin A, Hershkop Y, Cipok M, Cohen A, Leiba M. Immature Platelet Fraction as a Surrogate Marker of Thrombo-Inflammation in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Life. 2025; 15(12):1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121846

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuek, Adrian, Alexandra Zimin, Yael Hershkop, Michal Cipok, Amir Cohen, and Merav Leiba. 2025. "Immature Platelet Fraction as a Surrogate Marker of Thrombo-Inflammation in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients" Life 15, no. 12: 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121846

APA StyleDuek, A., Zimin, A., Hershkop, Y., Cipok, M., Cohen, A., & Leiba, M. (2025). Immature Platelet Fraction as a Surrogate Marker of Thrombo-Inflammation in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Life, 15(12), 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121846