Chemical Characteristics and Biological Potential of Prunus laurocerasus Fruits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Fruit Extraction

2.3. Geometric Parameters

2.4. Color Characteristics

2.5. Celullose

2.6. Sugar and Polyol Content by HPLC-RID Method

2.7. Total Phenols and Flavonoids Content

2.8. Antioxidant Activity

2.9. Antimicrobial Activity

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical Characteristics

3.1.1. Geometric Parameters Measurements

3.1.2. Color Characteristics

3.2. Chemical Composition

3.2.1. Titratable Acidity (TA), pH, Total Soluble Solids (TSS), Maturity Index, Moisture, and Ash

3.2.2. Polyuronide Content, Degree of Esterification of Pectin, Cellulose, and Total Lipids of Laurel Cherry, Variety Novita Fruit

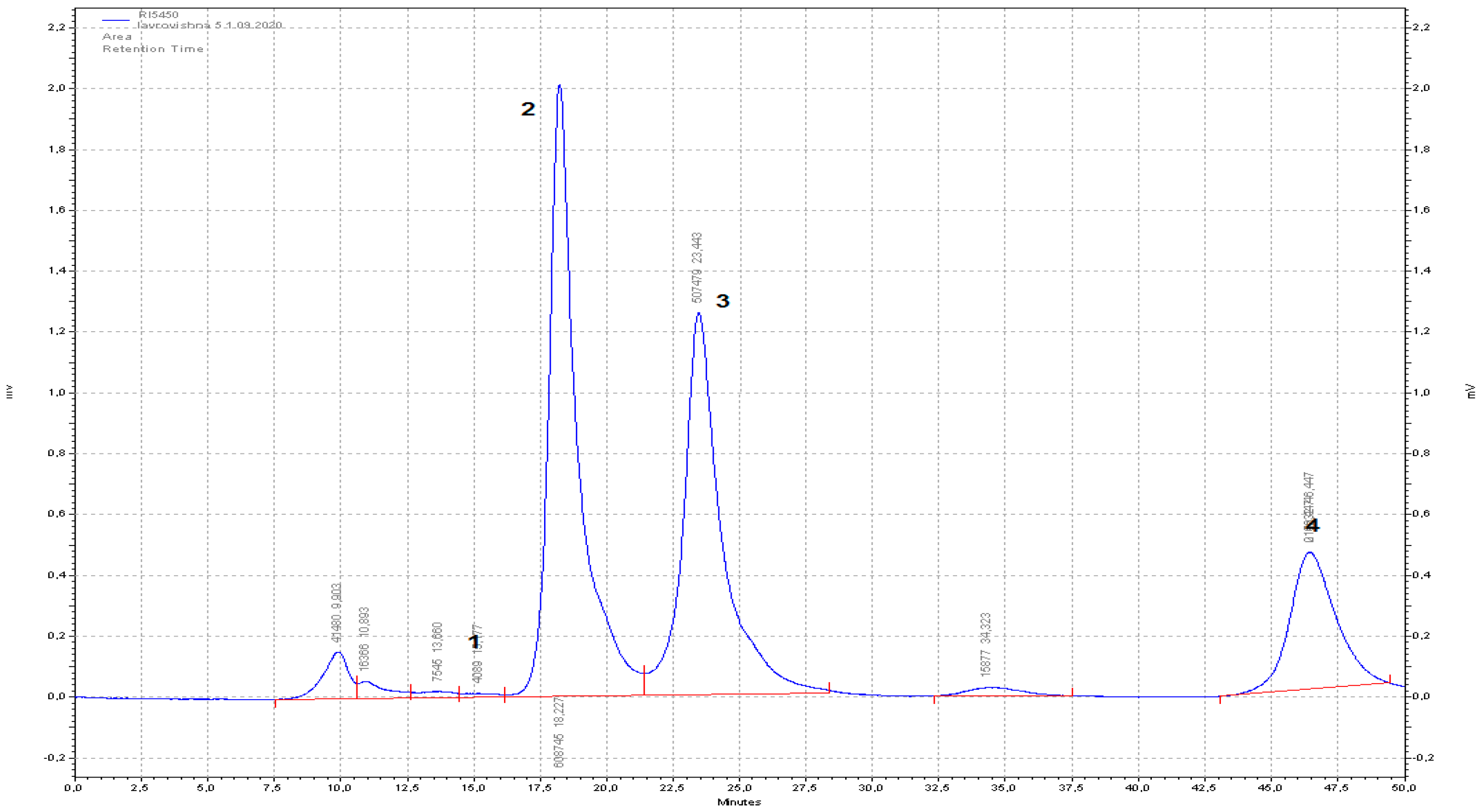

3.2.3. Sugar Content in the Laurocerasus officinalis, Novita Fruits

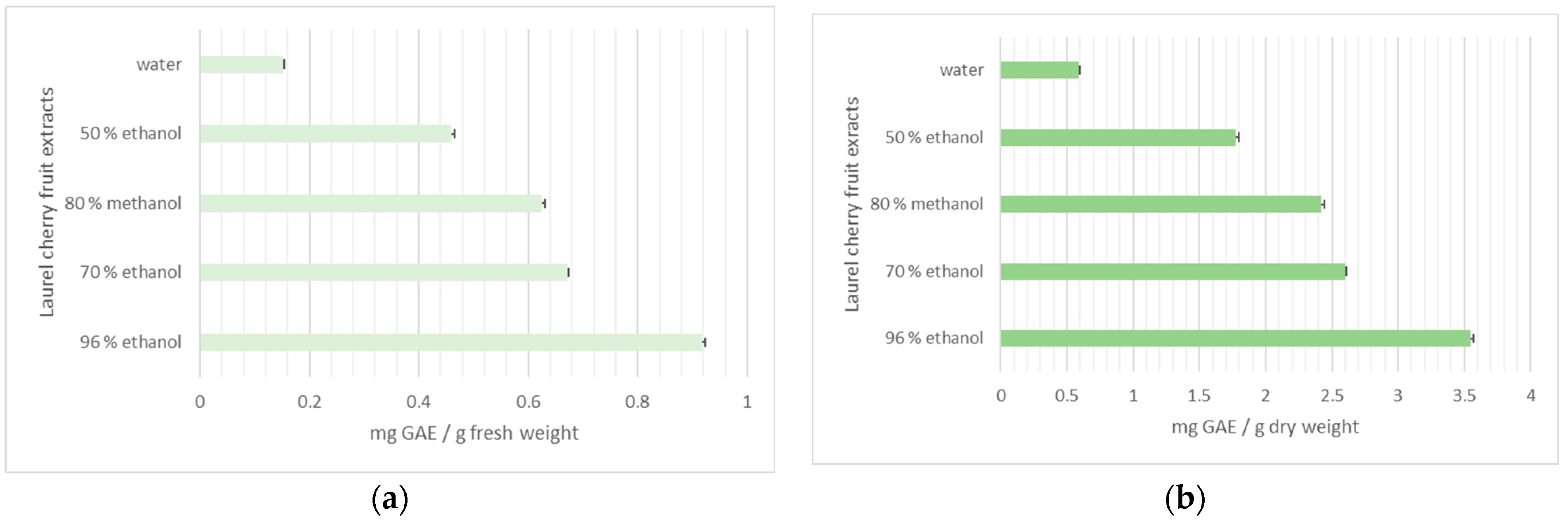

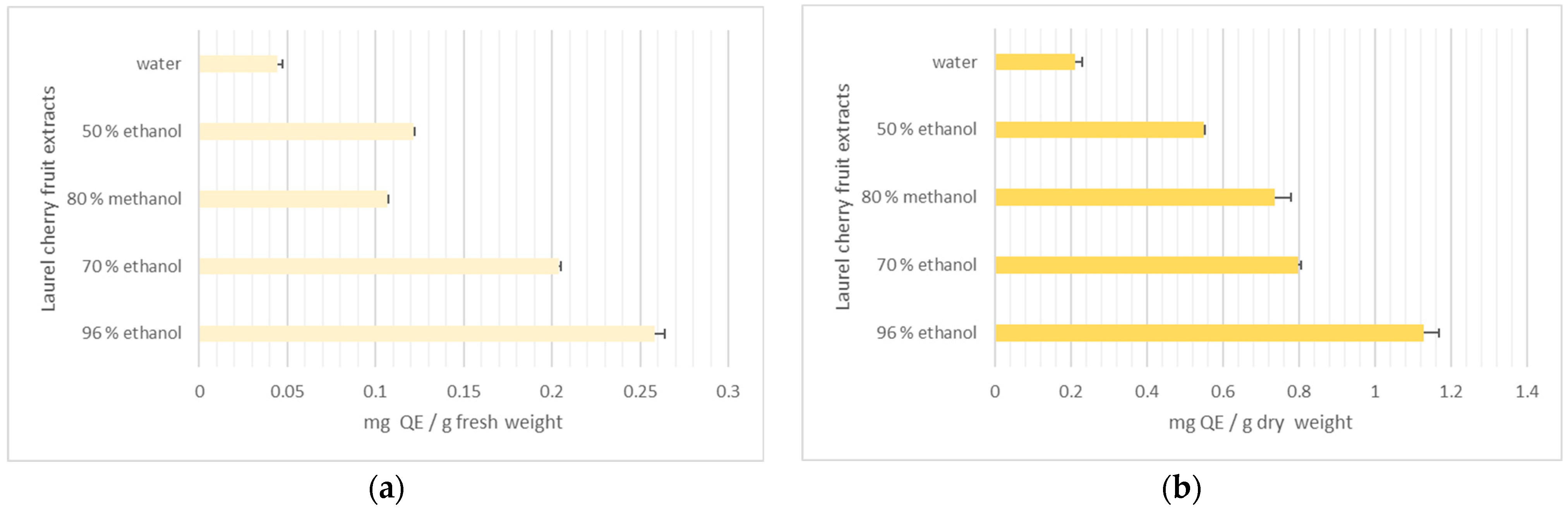

3.2.4. Total Phenolic Content and Flavonoids

3.3. Biological Experiments

3.3.1. Antioxidant Activity Measurements

3.3.2. Correlation Between the Total Phenolic Content, Total Flavonoid Content, and the Antioxidant Activity

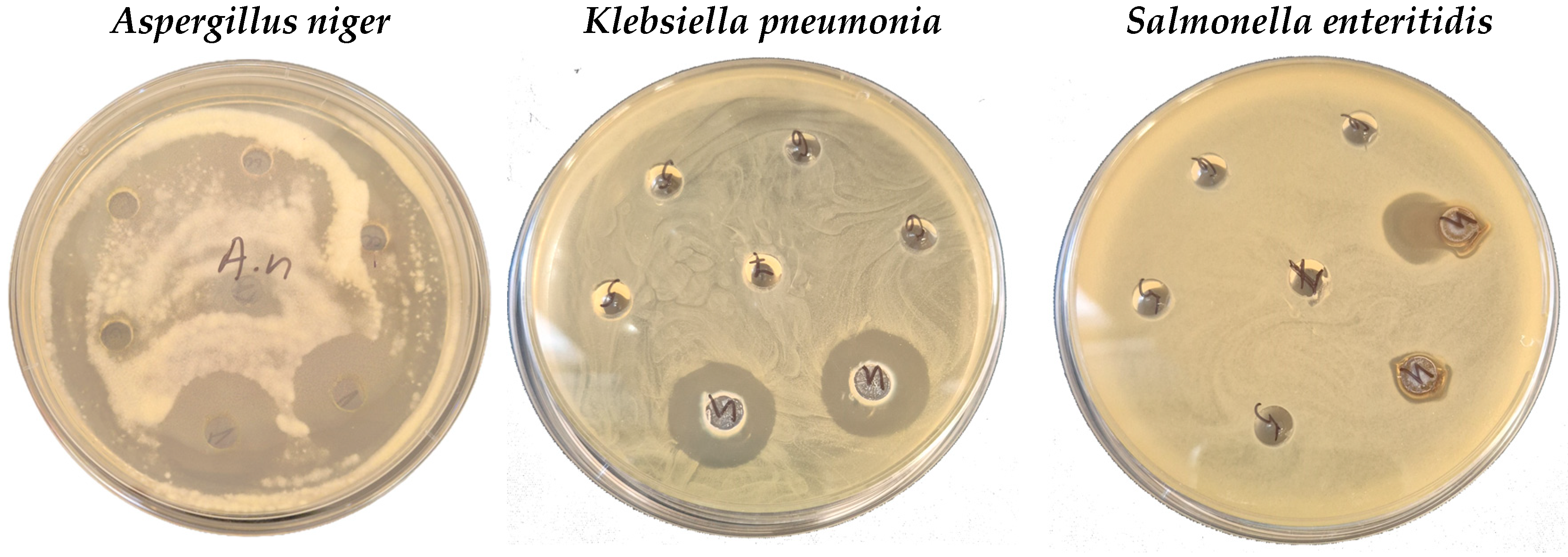

3.3.3. Antimicrobial Activity Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam, A. ‘Kiraz’ cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus). N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2002, 30, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, K.C.; Akir, B.; Kazaz, S. An important genetic resource for Turkey, Cherry laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roemer). Acta Hortic. 2011, 890, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, E.; Saracoglu, O.; Polatci, H. Physico-mechanical, colour and chemical properties of selected cherry laurel genotypes of Turkey. Adv. Agric. Sci. 2018, 6, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Halilova, H.; Ercisli, S. Several physico-chemical characteristic of cherry laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) fruits. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2010, 24, 1970–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulusoglu, M. The cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus L.) tree selection. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 3574–3582. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, F.A. Studies on water soluble sugar and sugar alcohol in cultivar and wild forms of Laurocerasus officinalis Roem. Pak. J. Bot. 1997, 29, 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbolat, İ.; Kartal, M. Prulaurasin content of leaves, kernels and pulps of Prunus lauracerasus L. (Cherry Laurel) during ripening. J. Res. Pharm. 2019, 22, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, F.A.; Kadioglu, A.; Reunanen, M.; Var, M. Sugar composition in fruits of Laurocerasus officinalis Roem. and its three cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1997, 10, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyana-Pathirana, C.M.; Shahidi, F.; Alasalvar, C. Antioxidant activity of cherry laurel fruit (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) and its concentrated juice. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, C.; Yilmaz, K.; Ozturk, S.; Karpuz, O. Vinegar production from different cherry laurel fruits and investigation of some of their physicochemical properties. J. Food Saf. Food Qual. 2024, 75, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konak, Ü.I.; Erem, F.; Altindağ, G.; Certel, M. Effect of Cherry Laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) Incorporation on Physical, Textural and Functional Properties of Cakes and Cookies. Uludağ Univ. J. Agric. Fac. 2015, 29, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Temiz, H.; Tarakçı, Z.; Islam, A. Effect of cherry laurel marmalade on physicochemical and sensorial characteristics of the stirred yogurt during storage time. GIDA 2014, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, F.A.; Reunanen, M.; Küçükislamoğlu, M.; Var, M. Seed fatty acid composition in wild form and cultivars of Laurocerasus officinalis Roem. Pak. J. Bot. 1995, 27, 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kolaylı, S.; Küçük, M.; Duran, C.; Candan, F.; Dinçer, B. Chemical and antioxidant properties of Laurocerasus officinalis Roem. (cherry laurel) fruit grown in the Black Sea region. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7489–7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H.; Ercisli, S.; Narmanlioglu, H.K.; Guclu, S.; Akbulut, M.; Turkoglu, Z. The main quality attributes of non-sprayed cherry laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) genotypes. Genetika 2014, 46, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşilada, E.; Sezik, E.; Honda, G.; Takaishi, Y.; Takeda, Y.; Tanaka, T. Traditional medicine in Turkey IX: Folk medicine in north-west Anatolia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 64, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdemoglu, N.; Küpeli, E.; Yeşilada, E. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activity assessment of plants used as remedy in Turkish folk medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasalvar, C.; Al-Farsi, M.; Shahidi, F. Compositional characteristics and antioxidant components of cherry laurel varieties and pekmez. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahalil, F.Y.; Şahin, H. Phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of Cherry Laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) sampled from Trabzon region, Turkey. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 16293–16299. [Google Scholar]

- Colak, A.; Özen, A.; Dincer, B.; Güner, S.; Ayaz, F.A. Diphenolases from two cultivars of cherry laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) fruits at an early stage of maturation. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayla, S.; Okur, M.E.; Günal, M.Y.; Özdemir, E.M.; Çiçek Polat, D.; Yoltaş, A.; Biçeroğlu, Ö.; Karahüseyinoğlu, S. Wound healing effects of methanol extract of Laurocerasus officinalis Roem. Biotech. Histochem. 2019, 94, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, H.; Uslu, G.A.; Özen, H.; Karaman, M. Effects of different doses of Prunus laurocerasus L. leaf extract on oxidative stress, hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia induced by type I diabetes. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2018, 17, 430–436. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, K.; Karadağ, A.; Sağdıç, O. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Capacity, Antimicrobial Effect, and In Vitro Digestion Process of Bioactive Compounds of Cherry Laurel Leaves Extracts. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 29, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyhan, O.; Demïr, T.; Yurt, B. Determination of antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds and biochemical properties of cherry laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis R.) grown in Sakarya Turkey. Bahçe 2018, 47, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- İslam, A.; Karakaya, O.; Gün, S.; Karagöl, S.; Öztürk, B. Fruit and biochemical characteristics of Selected Cherry Laurel Genotypes. Ege Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Derg. 2020, 57, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, F.; Gago, S.; Oladele, R.; Denning, D. Global and Multi-National Prevalence of Fungal Diseases—Estimate Precision. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, N.; Caplan, T.; Cowen, L.E. Molecular Evolution of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 71, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambugala, K.M.; Daranagama, D.A.; Tennakoon, D.S.; Jayatunga, D.P.W.; Hongsanan, S.; Xie, N. Humans vs. Fungi: An Overview of Fungal Pathogens against Humans. Pathogens 2024, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Karhana, S.; Shamsuzzaman, M.; Khan, M.A. Recent Drug Development and Treatments for Fungal Infections. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 1695–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Sulaiman, T.; Al-Ahmed, S.H.; Buhaliqah, Z.A.; Buhaliqah, A.A.; AlYuosof, B.; Alfaresi, M.; Al Fares, M.A.; Alwarthan, S.; Alkathlan, M.S.; et al. Potential Strategies to Control the Risk of Antifungal Resistance in Humans: A Com-prehensive Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roemer, T.; Krysan, D.J. Antifungal Drug Development: Challenges, Unmet Clinical Needs, and New Approaches. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a019703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Molecular Mechanisms Governing Antifungal Drug Resistance. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, K.; Raycheva, T.s.; Cheschmedzhiev, I. Key to the Native and Foreign Vascular Plants in Bulgaria; Interactive extended and supplemented edition; Academic Publishing House of the Agrarian University: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2022; ISBN 978-954-517-313-4. (In Bulgarian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://bgflora.net/families/rosaceae/prunus/prunus_laurocerasus/prunus_laurocerasus_en.html (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Petkova, N.; Ivanov, I.; Denev, P.; Pavlov, A. Bioactive substance and free radical scavenging activities of flour from jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) tubers—A comparative study. Turk. J. Agric. Nat. Sci. 2014, 2, 1773–1778. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/142339 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Megat Ahmad Azman, P.N.; Shamsudin, R.; Che Man, H.; Ya’acob, M.E. Some Physical Properties and Mass Modelling of Pepper Berries (Piper nigrum L.), Variety Kuching, at Different Maturity Levels. Processes 2020, 8, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeel, E.H.; Khater, E.-S.G.; Bahnasawy, A.H.; Atawia, A.A.R. Some Physical and Chemical Properties of Mango Fruits. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2021, 59, 679–688. [Google Scholar]

- Tumbarski, Y.D.; Todorova, M.M.; Topuzova, M.G.; Georgieva, P.I.; Petkova, N.T.; Ivanov, I.G. Postharvest Biopreservation of Fresh Blueberries by Propolis-Containing Edible Coatings Under Refrigerated Conditions. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 10, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, B.C.K.; Dyer, E.B.; Feig, J.L.; Chien, A.L.; Bino, S.D. Research techniques made simple: Cutaneous colorimetry: A reliable technique for objective skin color measurement. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumbarski, Y.; Nikolova, R.; Petkova, N.; Ivanov, I.; Lante, A. Biopreservation of fresh strawberries by carboxymethyl cellulose edible coatings enriched with a bacteriocin of Bacillus methylotrophicus BM47. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumbarski, Y.; Petkova, N.; Todorova, M.; Ivanov, I.; Deseva, I.; Mihaylova, D.; Ibrahim, S.A. Effects of pectin-based edible coatings containing a bacteriocin of Bacillus methylotrophicus BM47 on the quality and storage life of fresh blackberries. Ital. J. Food. Sci. 2020, 32, 420–437. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 750:1998(E); Fruit and Vegetable Products—Determination of Titratable Acidity. International Organization Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/22569.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- AOAC Official Method 934.06; Moisture in Dried Fruits. AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2007. Available online: http://www.eoma.aoac.org/methods/info.asp?ID=21670 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- AOAC Official Method 940.26; Ash of Fruits and Fruit Products. AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2007. Available online: http://www.eoma.aoac.org/methods/info.asp?ID=15176 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Shelukhina, N.P.; Fedichkina, L.G. A rapid method for quantitative determination of pectic substances. Acta Bot. Neerl. 1994, 43, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavov, A.; Ognynanov, M.; Vasileva, I. Pectic polysaccharides extracted from pot marigold (Calendula officinalis) industrial waste. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, I.S.; Skokan, L.E.; Tsitovich, A.P. Technochemical and Microbiological Control in Confectionery Production: A Handbook; KolosS: Moscow, Russia, 2003. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Esringu, A.; Akšić, M.F.; Ercisli, S.; Okatan, V.; Gozlekci, S.; Cakir, O. Organic acids, sugars and mineral content of cherry laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) accessions in Turkey. Comptes Rendus Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2016, 69, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Current through revision 2, 2007; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikinova, R.; Petkova, N.; Hadjikinov, D.; Denev, P.; Hrusavov, D. Development and validation of HPLC-RID method for determination of sugars and polyols. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2017, 9, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, I.G.; Vrancheva, R.Z.; Marchev, A.S.; Petkova, N.T.; Aneva, I.Y.; Denev, P.P.; Georgiev, V.G.; Pavlov, A.I. Antioxidant activities and phenolic compounds in Bulgarian Fumaria species. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 296. [Google Scholar]

- Petkova, P.; Bileva, T.; Valcheva, E.; Dobrevska, G.; Grozeva, N.; Todorova, M.; Popov, V. Non-Polar Fraction Constituents, Phenolic Acids, Flavonoids and Antioxidant Activity in Fruits from Florina Apple Variety Grown under Different Agriculture Management. Nat. Life Sci. Commun. 2023, 22, e2023012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanakieva, V.; Parzhanova, A.; Dimitrov, D.; Vasileva, I.; Raeva, P.; Ivanova, S. Study on the Antimicrobial Activity of Medicinal Plant Extracts and Emulsion Products with Integrated Herbal Extracts. Agric. For. 2023, 69, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, D.; Serrano, M. Growth and ripening stage at harvest modulates postharvest quality and bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2013, 3, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Valero, D.; Serrano, M. (Eds.) Fruit ripening. In Postharvest Biology and Technology for Preserving Fruit Quality; CRC Press-Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2010; pp. 7–47. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Mula, H.M.; Castillo, S.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Valero, D.; Zapata, P.J.; Guillén, F.; Serrano, M. Organoleptic, nutritive and functional proper ties of sweet cherry as affected by cultivar and ripening stage. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2009, 15, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobiega, K.; Igielska, M.; Włodarczyk, P.; Gniewosz, M. The use of pullulan coatings with propolis extract to extend the shelf life of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) fruit. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardisson, A.; Rubio, C.; Martin, M.; Alvarez, R.; Diaz, E. Mineral composition of the banana (Musa acuminata) from the island of Tenerife. Food Chem. 2001, 112, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, F.; Ercisli, S.; Yilmaz, S.O.; Hegedus, A. Estimation of Certain Physical and Chemical Fruit Characteristics of Various Cherry Laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis Roem.) Genotypes. Hortic. Sci. 2011, 46, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalisi, A.; O’Connell, M.G. Relationships between Soluble Solids and Dry Matter in the Flesh of Stone Fruit at Harvest. Analytica 2021, 2, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, M.; Macit, I.; Ercisli, S.; Koc, A. Evaluation of 28 cherry laurel (Laurocerasus officinalis) genotypes in the Black Sea region, Turkey. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2007, 35, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Vardal, E. Pomological Characteristics of Cherry Laurel (Prunus laurocerasus L.) Grown in Rize. Acta Hort. 2009, 818, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silué, Y.; Fawole, O.A. Cluster analysis of Japanese plum cultivars for optimizing export handling conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 346, 114185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncül, N.; Karabiyikli, Ş. Factors Affecting the Quality Attributes of Unripe Grape Functional Food Products. J. Food Biochem. 2015, 39, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladaniya, M.S. Fruit Quality Control, Evaluation, and Analysis. In Citrus Fruit; Ladaniya, M.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanoz, Y.Y.; Okcu, Z. Biochemical content of cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus L.) fruits with edible coatings based on caseinat, Semperfresh and lecithin. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2022, 46, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenik, V.; Štampar, F.; Veberič, R. Anthocyanins and Fruit Colour in Plums (Prunus domestica L.) during Ripening. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.J. Fibre in enteral nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 1987, 20, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, S. Metabolic effects of dietary pectins related to human health. Food Technol. 2001, 41, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chandel, V.; Biswas, D.; Roy, S.; Vaidya, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, A. Current Advancements in Pectin: Extraction, Properties and Multifunctional Applications. Foods 2022, 11, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N.S.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Lee, W.Y. Pectin Hydrogels: Gel-Forming Behaviors, Mechanisms, and Food Applications. Gels 2023, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyoncu, İ.H.; Ersoy, N.; Elidemir, A.Y.; Dolek, C. Mineral and Some Physico-Chemical Composition of ‘Karayemis’ (Prunus laurocerasus L.) Fruits Grown in Northeast Turkey. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Biol. Biomol. Agric. Food Biotechnol. Eng. 2013, 7, 430–433. [Google Scholar]

- Borsani, J.; Budde, C.O.; Porrini, L.; Lauxmann, M.A.; Lombardo, V.A.; Murray, R.; Andreo, C.S.; Drincovich, M.F.; Lara, M.V. Carbon metabolism of peach fruit after harvest: Changes in enzymes involved in organic acid and sugar level modifications. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1823–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasalvar, C.; Chang, S.K. Antioxidants, polyphenols, and health benefits of cherry laurel: A review. J. Food Bioact. 2020, 10, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, O.F.; Demirkol, M.; Durmus, Y.; Tarakci, Z. Effects of drying method on the phenolics content and antioxidant activities of cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus L.). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.; Celik, S.M.; Karakaya, M.; Karakaya, O.; Islam, A.; Yarilgac, T. Storage temperature affects phenolic content, antioxidant activity and fruit quality parameters of cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus L.). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erguney, E.; Gulsunoglu, Z.; Durmus, E.F.; Akyilmaz, M.K. Improvement of physical properties of cherry laurel powder. Acad. Food 2017, 13, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bilenler Koc, T.; Karabulut, I. Effect of Altitude and Location on Compositions and Antioxidant Activity of Laurel Cherry (Prunus Laurocerasus L.). JAFAG 2023, 40, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabegović, I.T.; Stojičević, S.S.; Veličković, D.T.; Todorović, Z.B.; Nikolić, N.Č.; Lazić, M.L. The effect of different extraction techniques on the composition and antioxidant activity of cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus) leaf and fruit extracts. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014, 54, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahan, Y.; Cansev, A.; Celik, G.; Cinar, A. Determination of Various Chemical Properties, Total Phenolic Contents, Antioxidant Capacity and Organic Acids in Laurocerasus officinalis Fruits. Acta Hortic. 2012, 939, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celep, E.; Aydın, A.; Yesilada, E. A comparative study on the in vitro antioxidant potentials of three edible fruits: Cornelian cherry, Japanese persimmon and cherry laurel. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3329–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, D.; Popova, A.; Desseva, I.; Petkova, N.; Stoyanova, M.; Vrancheva, R.; Slavov, A.; Slavchev, A.; Lante, A. Comparative Study of Early- and Mid-Ripening Peach (Prunus persica L.) Varieties: Biological Activity, Macro-, and MicroNutrient Profile. Foods 2021, 10, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, D.; Ribarova, F.; Atanassova, M. Total phenolics and total flavonoids in bulgarian fruits and vegetables. J. Univ. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2005, 40, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Denev, P.; Lojek, A.; Ciz, M.; Kratchanova, M. Antioxidant activity and polyphenol content of Bulgarian fruits, Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 19, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Bi, J.; Li, X.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, X. Antioxidant profile of thinned young and ripe fruits of Chinese peach and nectarine varieties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2020, 23, 1272–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanoglu, E.; Boyacioglu, D.; de Vos, R.C.; Hall, R.D.; Beekwilder, J. Procyanidins in fruit from sour cherry (Prunus cerasus) differ strongly in chain length from those in laurel cherry (Prunus laurac erasus) and Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas). J. Berry Res. 2011, 1, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, C. Major phenolics in apple and their contribution in the total antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkova, N.T.; Kuzmanova, S.; Bileva, T.; Valcheva, E.; Dobrevska, G.; Grozeva, N.; Popov, V. Influence of conventional and organic agriculture practices on the total phenols and antioxidant potential of Florina apple fruits. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1031, 012088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, M.T.T.; Wibowo, D.; Rehm, B.H.A. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özçelik, E.; Uysal Pala, Ç. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of cherry laurel leaf and fruit extracts. In Proceedings of the Istanbul International Modern Scientific Research Congress-III, İstanbul, Turkey, 6–8 May 2022; pp. 1131–1138. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Weight (g) | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| Width (mm), W | 12.2 ± 0.2 |

| Length (mm), L | 14.7 ± 0.3 |

| Thickness, (mm) T | 15.1 ± 0.4 |

| GDM, (mm) | 13.9 ± 0.1 |

| Spherisity, (%) | 94.6 ± 2.2 |

| Surface area, (cm2) | 6.1 ± 0.1 |

| Color Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| L* | 26.38 ± 0.28 |

| a* | 0.89 ± 0.02 |

| b* | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| C* | 0.91 ± 0.07 |

| hue angle h° | 13.09 ± 0.64 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 4.54 ± 0.01 |

| total acidity (%) | 0.45 ± 0.01 |

| TSS, Brix (%) | 17.67 ± 0.58 |

| moisture (%) | 74.19 ± 1.19 |

| ash (%) | 0.83 ± 0.09 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| polyuronic acid content (%) | 3.33 ± 0.23 |

| degree of esterification (%) | 56.47 ± 7.01 |

| celulose (%) | 0.36 ± 0.08 |

| total lipids (%) | 0.85 ± 0.04 |

| DPPH | ABTS | FRAP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 96% ethanol | 5.90 a ± 0.54 | 8.28 a ± 0.16 | 6.79 a ± 0.23 |

| 22.85 b ± 0.83 | 32.04 b ± 0.25 | 26.28 b ± 0.91 | |

| 70% ethanol | 4.46 a ± 0.22 | 6.27 a ± 0.30 | 5.06 a ± 0.04 |

| 17.29 b ± 0.73 | 24.27 b ± 0.14 | 19.59 b ± 0.16 | |

| 80% methanol | 4.31 a ± 0.80 | 5.60 a ± 0.40 | 3.77 a ± 0.05 |

| 16.70 b ± 0.91 | 21.69 b ± 0.18 | 14.60 b ± 0.18 | |

| 50% ethanol | 2.78 a ± 0.23 | 4.14 a ± 0.14 | 2.83 a ± 0.14 |

| 10.76 b ± 0.67 | 16.04 b ± 0.54 | 10.95 b ± 0.67 | |

| water | 0.45 a ± 0.05 | 0.97 a ± 0.02 | 0.57 a ± 0.01 |

| 1.76 b ± 0.07 | 3.75 b ± 0.34 | 2.24 b ± 0.19 |

| Inhibition Zone, mm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested Microorganism | Water Extract | Methanol Extract | Nystatin | Penicillin |

| B. subtilis | 0 ± 0.00 | 13 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| B. amyloliquefaciens | 0 ± 0.00 | 12 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| S. aureus | 0 ± 0.00 | 17 ± 0.00 | n.a. | 30 |

| L. monocytogenes | 8 ± 0.00 | 15 ± 0.00 | n.a. | 20 |

| E. faecalis | 0 ± 0.00 | 13 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| M. luteus | 15 ± 0.00 | 20 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| S. enteritidis | 8 ± 0.00 | 17 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| S. typhimurium | 0 ± 0.00 | 17 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| Klebsiella sp. | 0 ± 0.00 | 20 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| E. coli | 0 ± 0.00 | 13 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| P. vulgaris | 0 ± 0.00 | 12 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| P. aeruginosa | 0 ± 0.00 | 13 ± 0.00 | n.a. | - |

| C. albicans | 0 ± 0.00 | 0 ± 0.00 | 21 | n.a. |

| S. cerevisiae | 0 ± 0.00 | 12 ± 0.00 | 18 | n.a. |

| A. niger | 0 ± 0.00 | 25 ± 0.00 | 18 | n.a. |

| A. flavus | 0 ± 0.00 | 20 ± 0.00 | 18 | n.a. |

| Penicillium sp. | 0 ± 0.00 | 22 ± 0.00 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Rhizopus spp. | 0 ± 0.00 | 20 ± 0.00 | n.a. | n.a. |

| F. moniliforme | 0 ± 0.00 | 20 ± 0.00 | 15 | n.a. |

| Mucor spp. | 0 ± 0.00 | 8 ± 0.00 | n.a. | n.a. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Todorova, M.; Petkova, N.; Ivanov, I.; Tumbarski, Y.; Yanakieva, V.; Vasileva, I.; Barakova, Y.; Cherneva, E.; Nikolova, S. Chemical Characteristics and Biological Potential of Prunus laurocerasus Fruits. Life 2025, 15, 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121847

Todorova M, Petkova N, Ivanov I, Tumbarski Y, Yanakieva V, Vasileva I, Barakova Y, Cherneva E, Nikolova S. Chemical Characteristics and Biological Potential of Prunus laurocerasus Fruits. Life. 2025; 15(12):1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121847

Chicago/Turabian StyleTodorova, Mina, Nadezhda Petkova, Ivan Ivanov, Yulian Tumbarski, Velichka Yanakieva, Ivelina Vasileva, Yoana Barakova, Emiliya Cherneva, and Stoyanka Nikolova. 2025. "Chemical Characteristics and Biological Potential of Prunus laurocerasus Fruits" Life 15, no. 12: 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121847

APA StyleTodorova, M., Petkova, N., Ivanov, I., Tumbarski, Y., Yanakieva, V., Vasileva, I., Barakova, Y., Cherneva, E., & Nikolova, S. (2025). Chemical Characteristics and Biological Potential of Prunus laurocerasus Fruits. Life, 15(12), 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121847