Tai Chi Exercise and Bone Health in Women at Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Stages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Process

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Process

2.6. Risk of Bias and Quality of Methods Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Overall Analytical Model

2.7.2. Effect Size and Heterogeneity Assessment

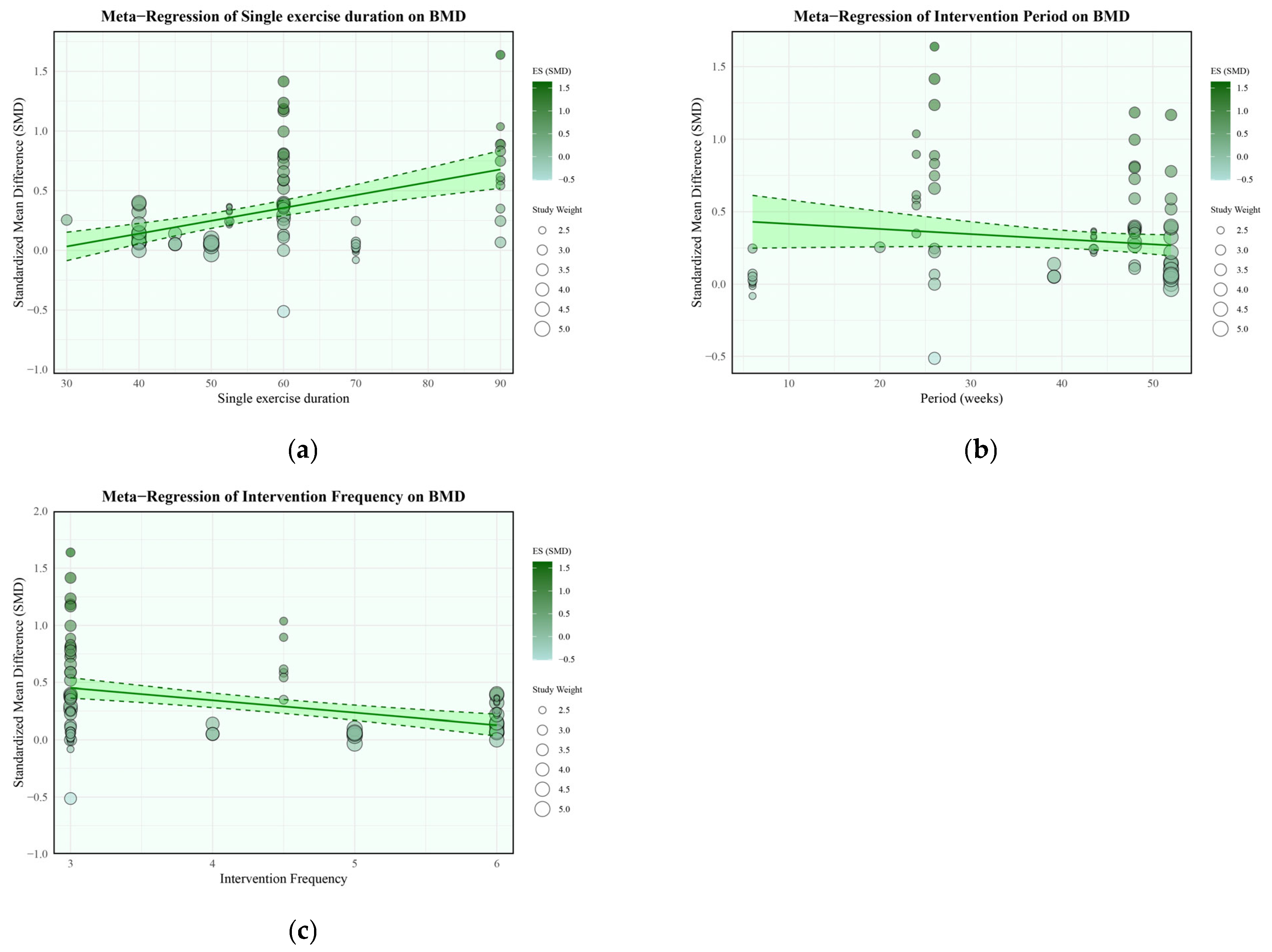

2.7.3. Moderator and Sensitivity Analyses

2.8. Certainty of the Evidence

3. Results

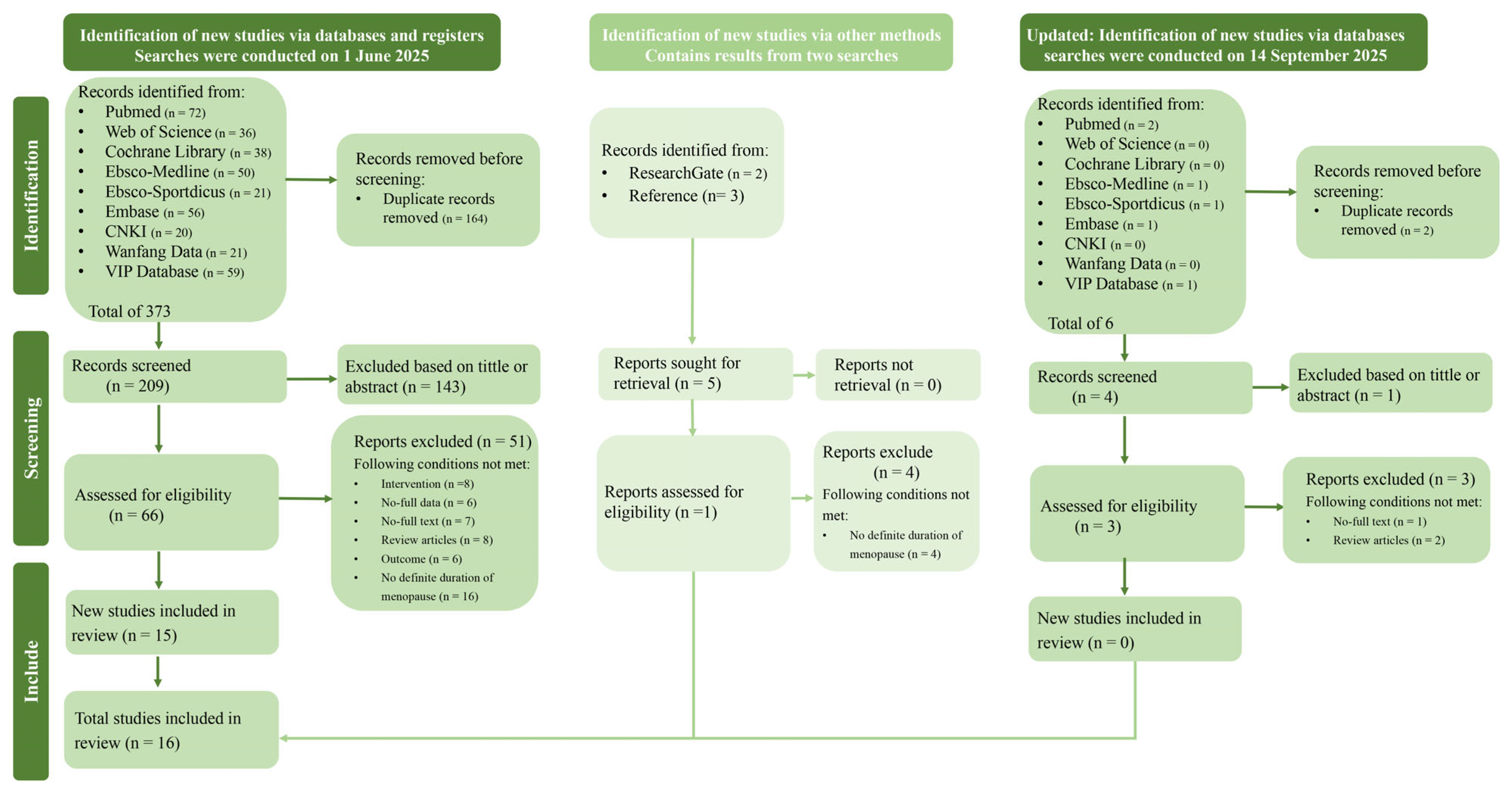

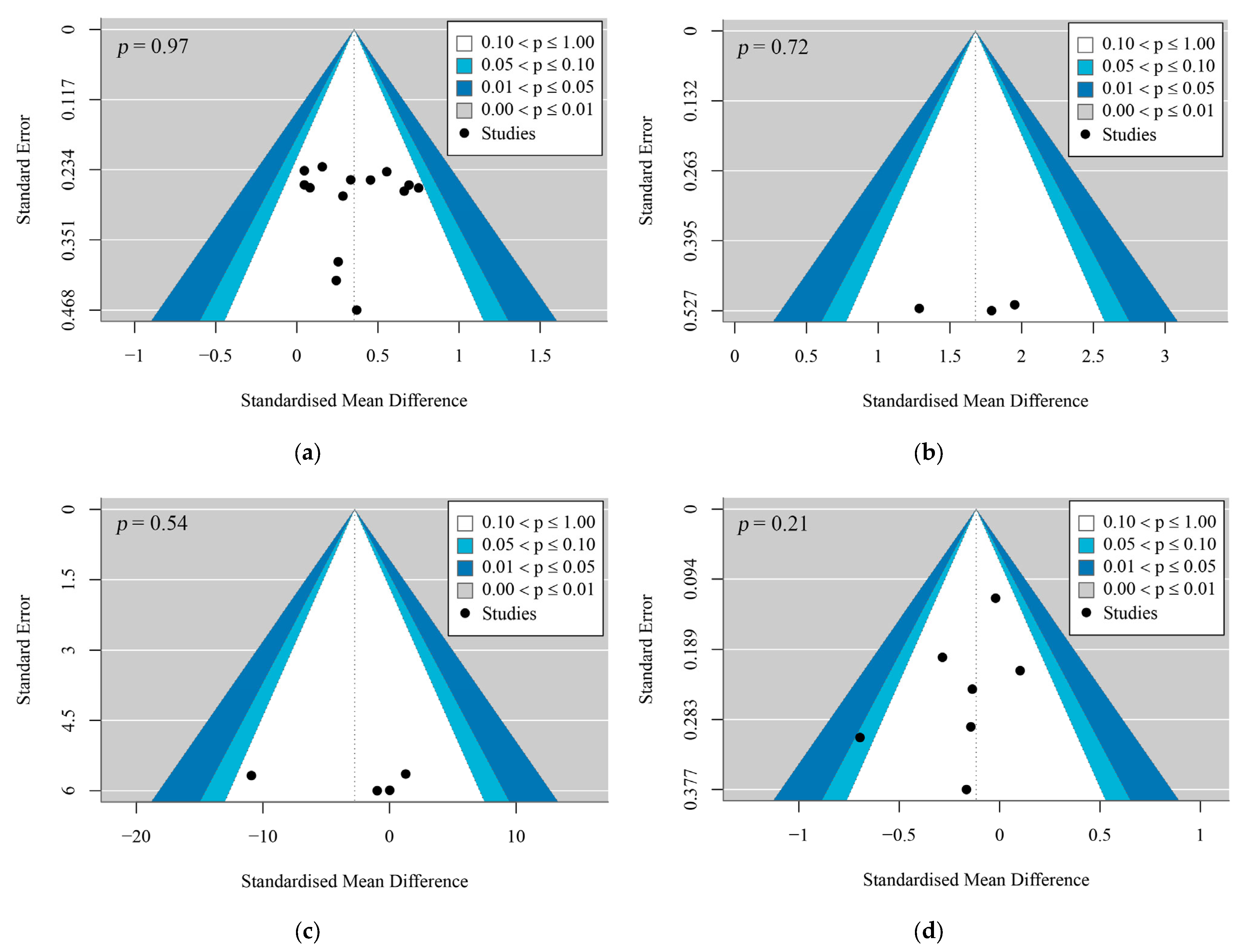

3.1. Studies Retrieved

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Primary Meta-Analysis Results

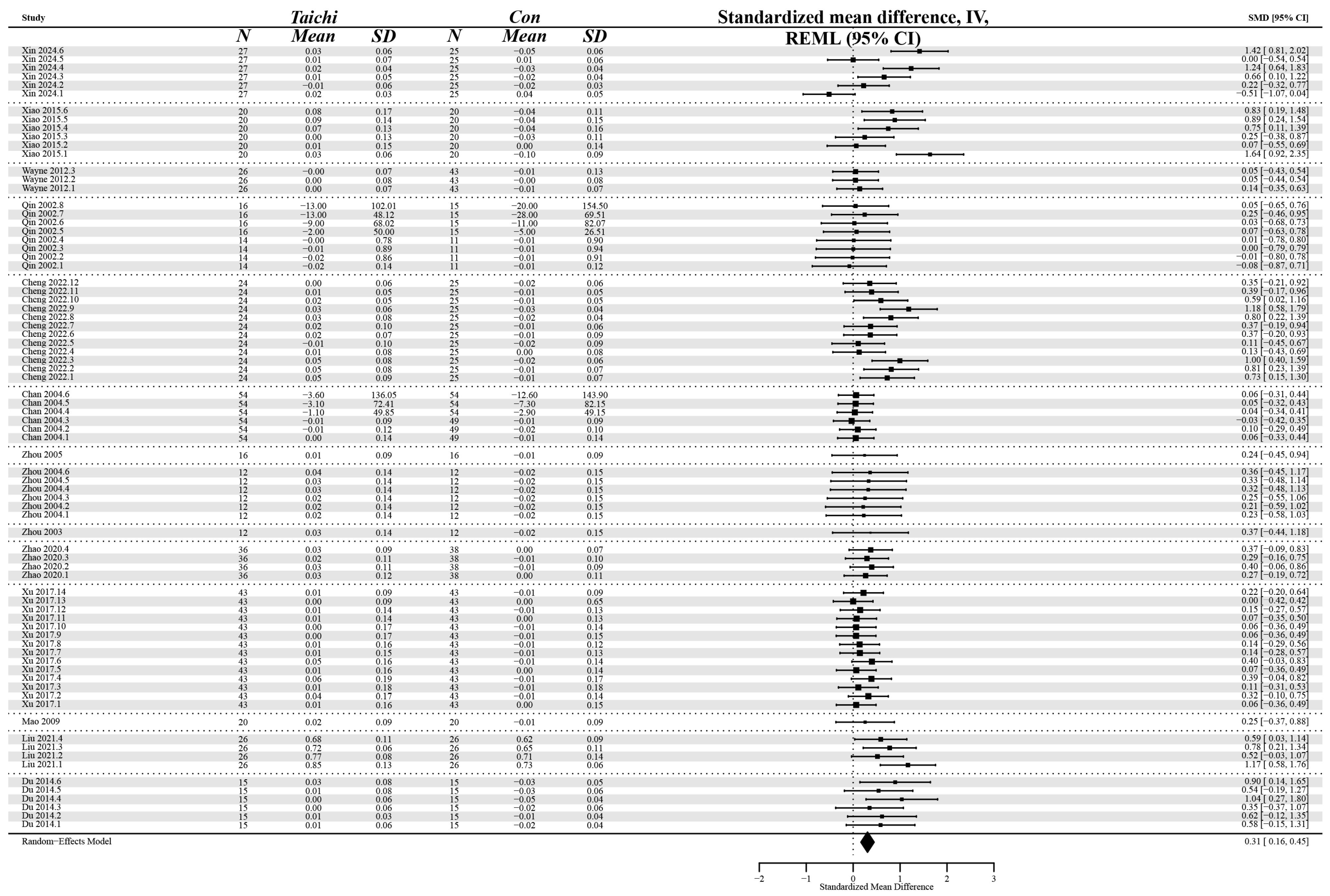

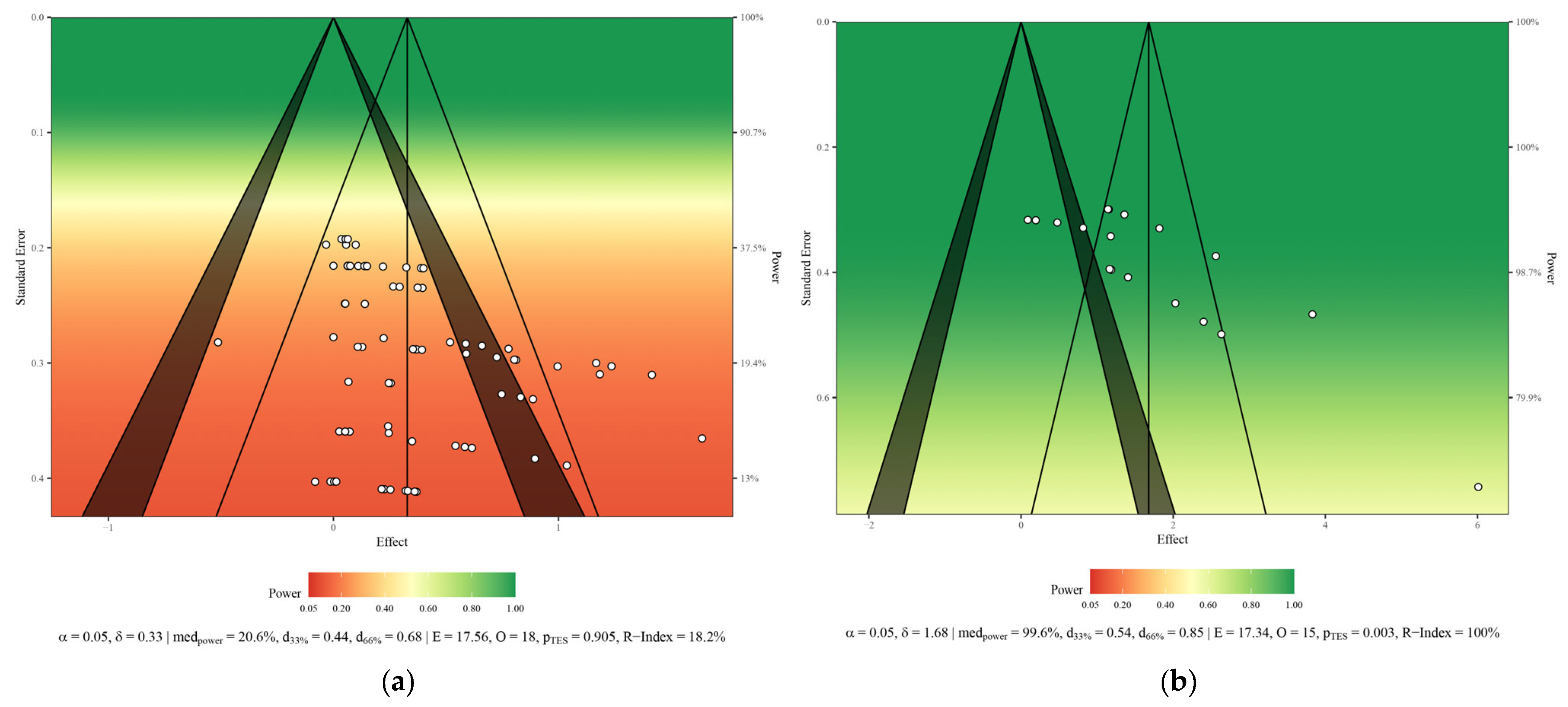

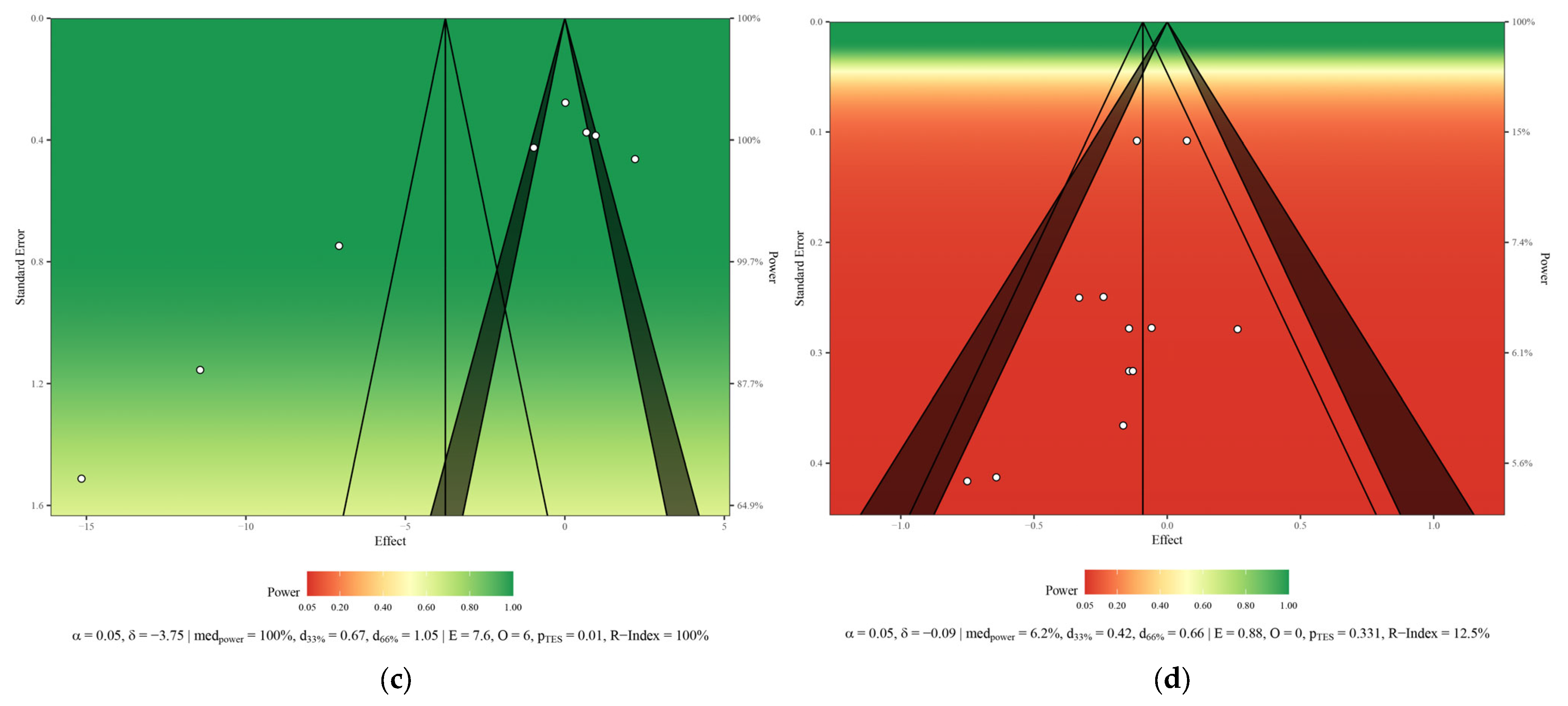

3.3.1. Bone Mineral Density

3.3.2. Bone Mineral Content

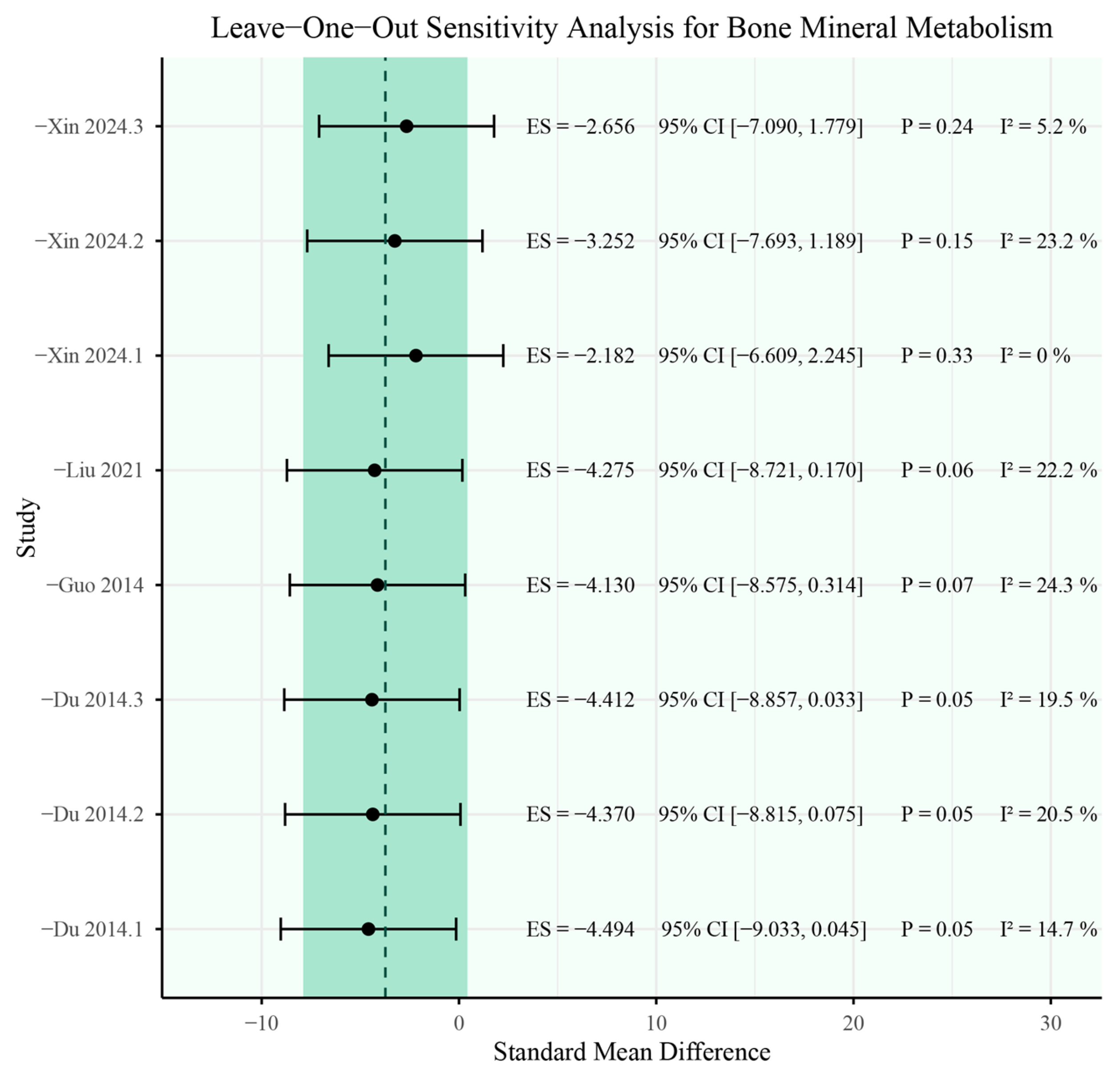

3.3.3. Bone Mineral Metabolism

3.3.4. Bone Turnover Markers

3.4. Secondary Meta-Analysis Results

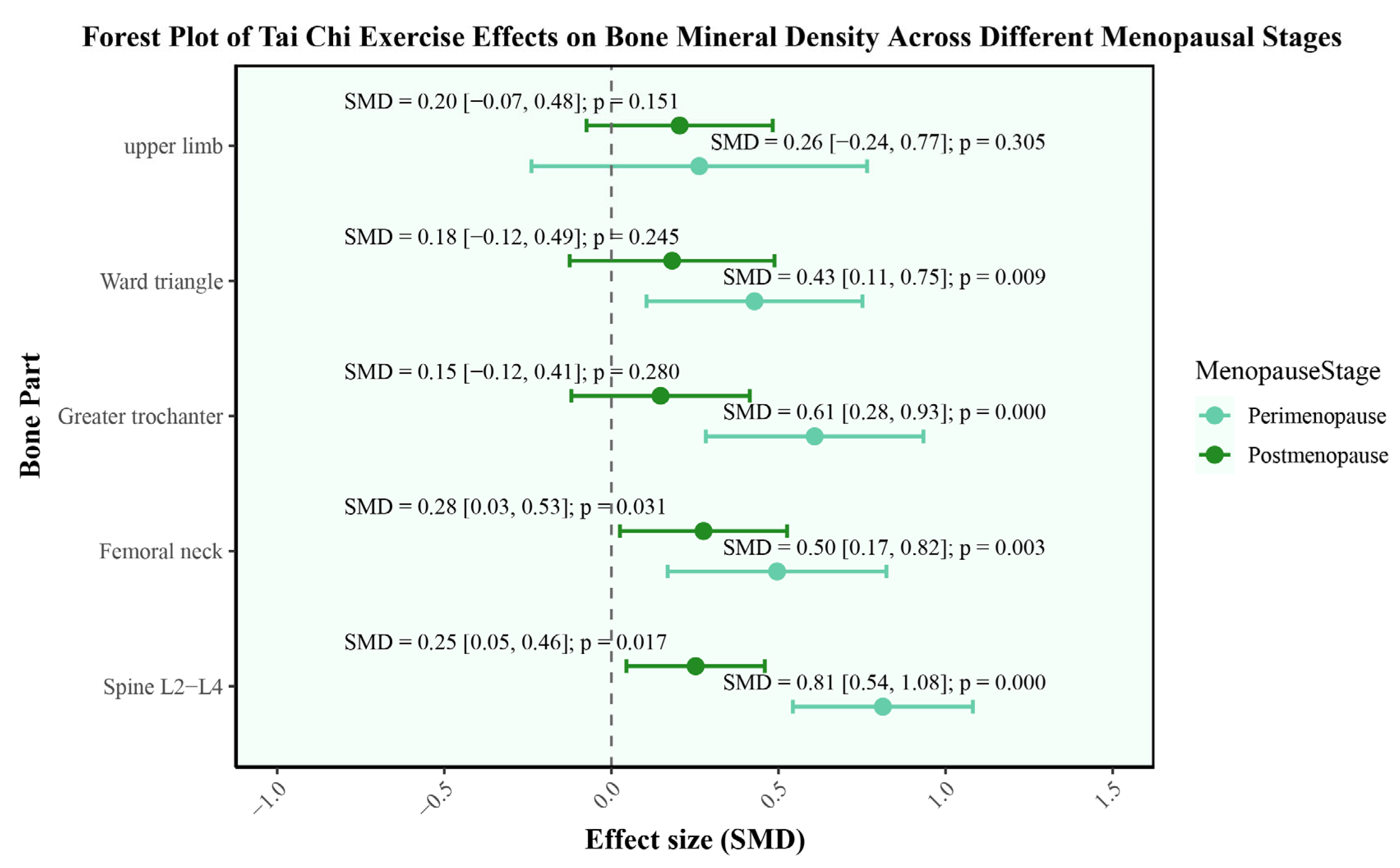

3.4.1. Bone Mineral Density

3.4.2. Bone Mineral Content

3.4.3. Bone Mineral Metabolism

3.4.4. Bone Turnover Markers

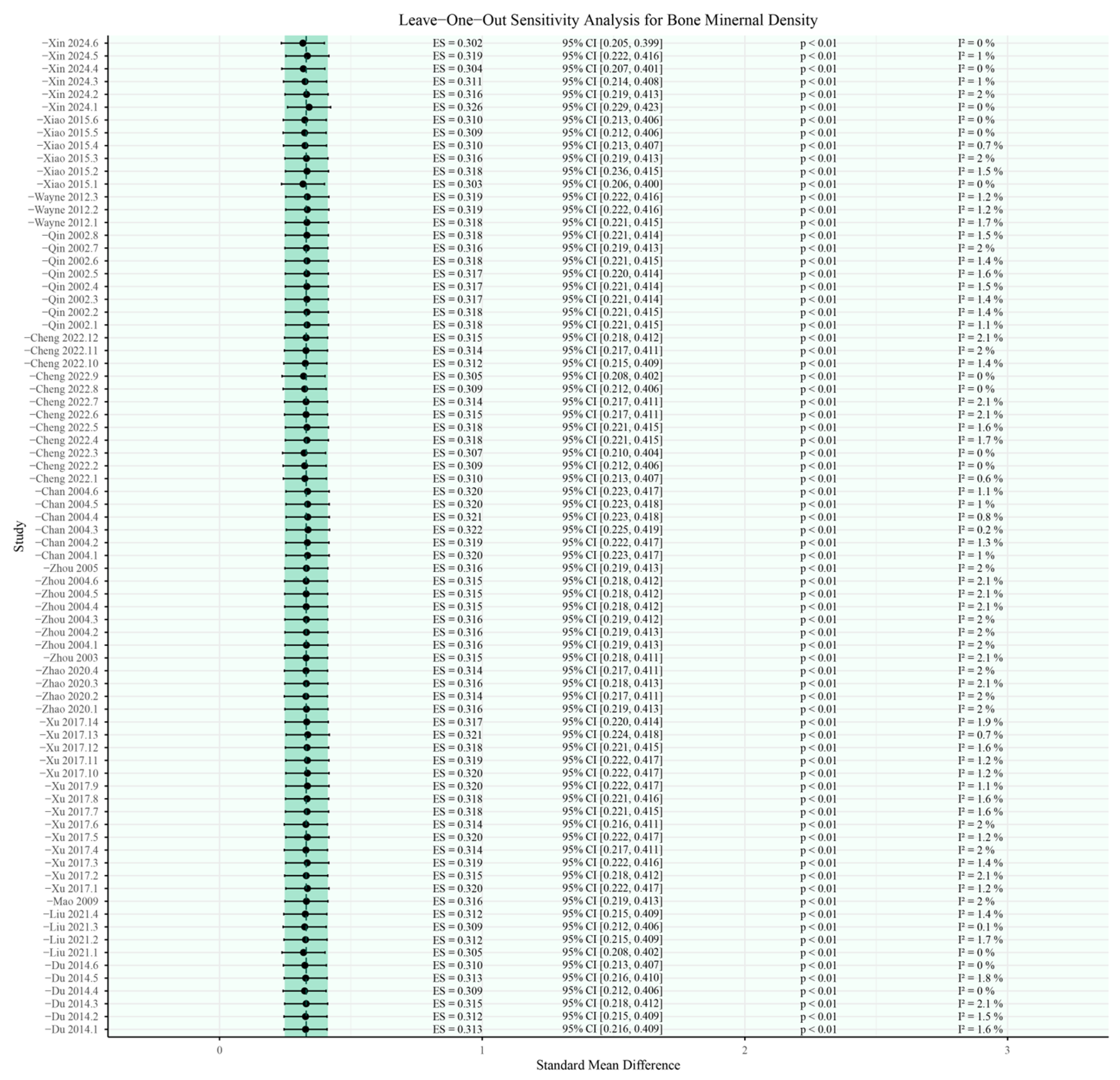

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

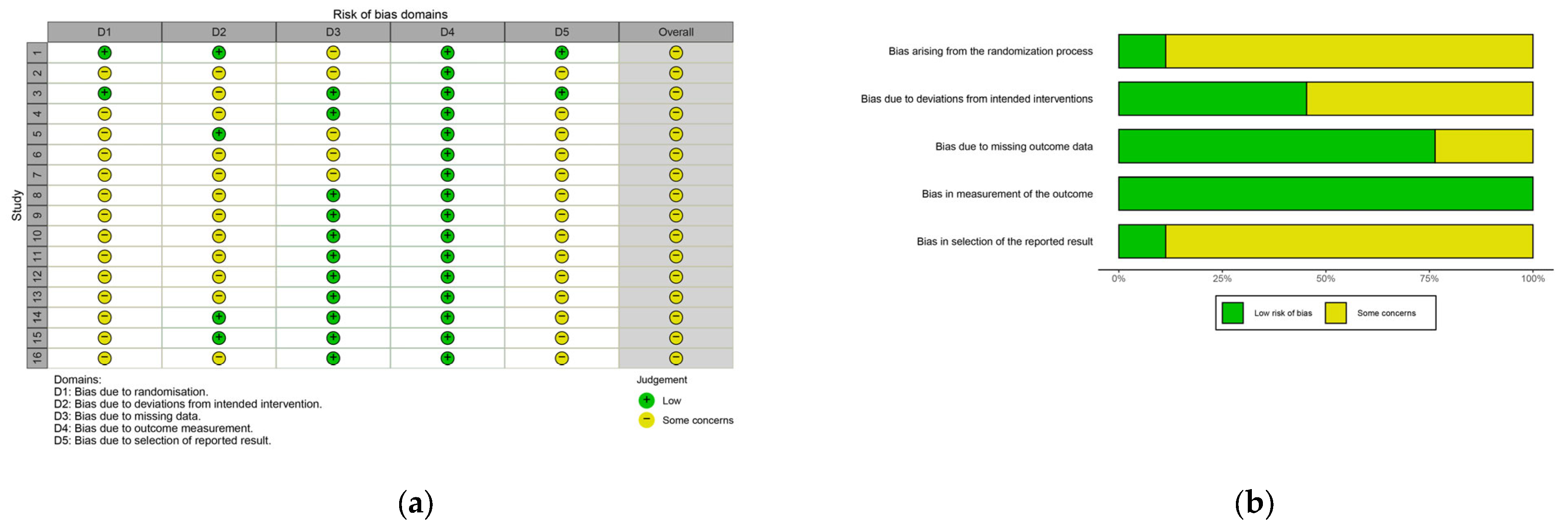

3.6. Risk of Bias and Methodological Quality

3.7. Results of the Certainty of the Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Bone Mineral Density

4.2. Bone Mineral Content

4.3. Bone Mineral Metabolism

4.4. Bone Turnover Markers

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section and Topic | Item | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 3 |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 3, 4 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 3 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | 3 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 3 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 4, 5 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, timepoints, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | 4 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 4 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 5, 6 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | 6 |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | 6 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | 6 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | 6 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | 6 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | 6 | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | 6 | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | 5, 6 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | 6, 7 |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 7 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | n/a | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 8, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | 17, 18 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | 8, 9, 10 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarize the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | 8, 9, 10 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was performed, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | 8, 9, 10 | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | 17 | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | 17, 18 |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | 19 |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 20 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 21, 22, 23 | |

| Other Information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | 3 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | 3 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | n/a | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | 28 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 28 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | n/a |

Appendix B

| Database | Search Strategy | Number of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((tai chi) OR(taiji) OR(tai ji quan) OR(tai-chi) OR(tai chi chuan) OR(shadow boxing)) AND((menopause) OR(menopausal women) OR(postmenopausal women) OR(middle-aged women) OR(climacteric)) AND((bone mineral density) OR(BMD) OR(osteoporosis) OR(bone health) OR(bone loss) OR(bone metabolism) OR(bone turnover) OR(bone fragility) OR(skeletal health) OR(bone remodeling) OR(bone strength)) | 72 |

| Web of science | ((TI = tai chi) OR(TI = taiji) OR(TI = tai ji quan) OR(TI = tai-chi) OR(TI = tai chi chuan) OR(TI = shadow boxing)) AND((AB = menopause) OR(AB = menopausal women) OR(AB = postmenopausal women) OR(AB = middle-aged women) OR(AB = climacteric)) AND((AB = bone mineral density) OR(AB = BMD) OR(AB = osteoporosis) OR(AB = bone health) OR(AB = bone loss) OR(AB = bone metabolism) OR(AB = bone turnover) OR(AB = bone fragility) OR(AB = skeletal health) OR(AB = bone remodeling) OR(AB = bone strength)) | 36 |

| Cochrane library | #1((tai chi) OR(taiji) OR(tai ji quan) OR(tai-chi) OR(tai chi chuan) OR(shadow boxing)):ti,ab,kw #2((menopause) OR(menopausal women) OR(postmenopausal women) OR(middle-aged women) OR(climacteric)):ti,ab,kw #3((bone mineral density) OR(BMD) OR(osteoporosis) OR(bone health) OR(bone loss) OR(bone metabolism) OR(bone turnover) OR(bone fragility) OR(skeletal health) OR(bone remodeling) OR(bone strength)):ti,ab,kw #4: #1 AND #2 AND#3 | 38 |

| Embase | #1((tai chi) OR(taiji) OR(tai ji quan) OR(tai-chi) OR(tai chi chuan) OR(shadow boxing)):ti,ab,kw #2((menopause) OR(menopausal women) OR(postmenopausal women) OR(middle-aged women) OR(climacteric)):ti,ab,kw #3((bone mineral density) OR(BMD) OR(osteoporosis) OR(bone health) OR(bone loss) OR(bone metabolism) OR(bone turnover) OR(bone fragility) OR(skeletal health) OR(bone remodeling) OR(bone strength)):ti,ab,kw #4: #1 AND #2 AND#3 | 56 |

| SPORTDiscus (Via EBSCO) | TX ((tai chi) OR(taiji) OR(tai ji quan) OR(tai-chi) OR(tai chi chuan) OR(shadow boxing)) AND((menopause) OR(menopausal women) OR(postmenopausal women) OR(middle-aged women) OR(climacteric)) AND((bone mineral density) OR(BMD) OR(osteoporosis) OR(bone health) OR(bone loss) OR(bone metabolism) OR(bone turnover) OR(bone fragility) OR(skeletal health) OR(bone remodeling) OR(bone strength)) | 21 |

| MEDLINE (Via EBSCO), | TX ((tai chi) OR(taiji) OR(tai ji quan) OR(tai-chi) OR(tai chi chuan) OR(shadow boxing)) AND((menopause) OR(menopausal women) OR(postmenopausal women) OR(middle-aged women) OR(climacteric)) AND((bone mineral density) OR(BMD) OR(osteoporosis) OR(bone health) OR(bone loss) OR(bone metabolism) OR(bone turnover) OR(bone fragility) OR(skeletal health) OR(bone remodeling) OR(bone strength)) | 50 |

| CNKI | SU = (‘太极’ + ‘太极拳’ + ‘太极运动’) and SU = (‘更年期女性’ + ‘更年期’ + ‘围绝经期’ + ‘绝经后女性’ + ‘中年女性’) and SU = (‘骨密度’ + ‘骨质疏松’ + ‘骨骼健康’ + ‘骨丢失’ + ‘骨代谢’ + ‘骨强度’ + ‘骨质重建’ + ‘骨骼脆性’ + ‘骨转化标志物’) | 20 |

| WanFang | 题名或关键词:((太极拳) OR(太极) OR(太极运动)) AND 题名或关键词:((更年期女性) OR(更年期) OR(围绝经期) OR(绝经后女性) OR(中年女性)) AND 题名或关键词:((骨密度) OR(骨质疏松) OR(骨骼健康) OR(骨丢失) OR(骨代谢) OR(骨强度) OR(骨质重建) OR(骨骼脆性) OR(骨转化标志物)) | 21 |

| VIP | ((M = 太极拳 OR M = 太极 OR M = 太极运动)) AND ((M = 更年期女性 OR M = 更年期 OR M = 围绝经期 OR M = 绝经后女性 OR M = 中年女性)) AND ((M = 骨密度 OR M = 骨质疏松 OR M = 骨骼健康 OR M = 骨丢失 OR M = 骨代谢) OR M = 骨强度 OR M = 骨质重建 OR M = 骨骼脆性 OR M = 骨转化标志物)) | 59 |

Appendix C

| First Author | Design | Participants | Terms | Menopausal Stage | Tai Chi Sessions | Con Sessions | Dur (min) | Fre | Wk | PEDro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Du, 2014 [56] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 15 Con—N: 15 Tai Chi—Age: 51.69 ± 3.18 Con—Age: 52.21 ± 3.01 | Tai Chi Rouli ball | Perimenopause | Tai Chi Rouli balll Routine 1–3 Intensity: Heart rate 110–130 beats/min. | The control group did not exercise and maintained their original lifestyle. | 90 | 4.5 | 24 | 6 |

| Guo, 2014 [58] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 16 Con—N: 10 Tai Chi—Age: 56.69 ± 3.50 Con—Age: 56.60 ± 4.30 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | 24-form Tai Chi Chuan Intensity: 50% HRmax at beginning; 60–80% HRmax in the whole process. | Con group engaged in daily physical activities, and no one withdrew midway throughout the entire process. | 60 | 6 | 24 | 5 |

| Mao, 2009 [59] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 20 Con—N: 20 Age: 56.78 ± 2.90 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | Prepare the activity time for 10 min, organize the activity time for 5–10 min, and formally engage in at least 30 min of moderate intensity Tai Chi exercise. Intensity: Heart rate 110 beats/min. | No intervention is made, the control group maintained their original lifestyle and received regular health education. | 30 | NR | 20 | 6 |

| Liu, 2021 [57] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 26 Con—N: 26 Age: 56.48 ± 3.41 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | Adopting 24 simplified Tai Chi exercises, guided by professional Tai Chi coaches, strictly following the requirements of Tai Chi training during practice, emphasizing on techniques, moves, and thoughts. Intensity: The standard heart rate during exercise is “170-age”. | The subjects did not engage in long-term exercise of Tai Chi, but some individuals occasionally exercised | 60 | 3 | 52 | 6 |

| Xu, 2017 [61] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 43 Con—N: 43 Tai Chi—Age: 54–65 Con—Age: 53–67 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | Tai Chi group practice 24 simplified Tai Chi exercises. | Con group engaged in daily physical activities, and no one withdrew midway throughout the entire process. | 40 | 6 | 52 | 6 |

| Xue, 2015 [60] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 171 Con—N: 173 Tai Chi—Age: 62.1 ± 7.0 Con—Age: 64.0 ± 7.3 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | Regular health education is provided for the Tai Chi group, using a unified arrangement of bone health exercise content (Tai Chi) for training. Participants should participate in the exercise program in an organized and regular manner and record it. | The control group maintained their original lifestyle and received regular health education. | 30 | 4 | 104 | 6 |

| Zhao, 2020 [54] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 36 Con—N: 38 Tai Chi—Age: 49.7 ± 3.9 Con—Age: 49.7 ± 3.9 | Tai Chi Quan | Perimenopause | Under the guidance of a professional Tai Chi coach (group teaching), a 48 week 24 style simplified Tai Chi intervention will be conducted. Intensity: The subject’s heart rate should be controlled between 55% and 65% HRmax. If it exceeds the controlled heart rate, the subject’s exercise intensity should be appropriately reduced. | Do not engage in any other forms of exercise except for maintaining past lifestyle habits. | 60 | 3 | 48 | 7 |

| Zhou, 2003 [53] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 12 Con—N: 10 Tai Chi—Age: 57.10 ± 2.71 Con—Age: 55.96 ± 2.84 | Tai Chi Push hands | Postmenopause | In the early stage, the main focus is on fixed step push hand exercises, while in the later stage, the main focus is on active step push hand exercises, with increasing intensity and difficulty. | Not participating in sports activities and maintaining normal lifestyle habits. | 52.5 | 6 | 43.5 | 7 |

| Zhou, 2004 [62] | RCT | Tai Chi 1—N: 12 Tai Chi 2—N: 12 Con: 12 Age: 55.94 ± 2.83 | Tai Chi 1: Tai Chi Quan Tai Chi 2: Tai Chi Push hands | Postmenopause | The early stage mainly involves high posture training, while the later stage mainly involves low posture training, with increasing intensity and difficulty. | Not participating in sports activities and maintaining normal lifestyle habits. | 52.5 | 6 | 43.5 | 7 |

| Zhou, 2005 [55] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 16 Con—N: 16 Tai Chi—Age: 51.69 ± 3.18 Age: 57.21 ± 3.41 | Tai Chi Push hands | Postmenopause | Start with high posture training and gradually reduce body posture; In terms of footwork, perform fixed step push hand training in the early stage, and then gradually transition to active step training. | Not participating in sports activities and maintaining normal lifestyle habits. | 52.5 | 6 | 43.5 | 7 |

| Chan, 2004 [17] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 54 Con—N: 54 Tai Chi—Age: 54.4 ± 3.3 Con—Age: 53.6 ± 3.2 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | Tai Chi group participated in a supervised Tai Chi exercise (Yang style). | Control subjects retained their sedentary lifestyle without participation in physical exercises. | 50 | 4.2 | 52 | 6 |

| Cheng, 2022 [15] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 24 Con—N: 25 Tai Chi—Age: 50.2 ± 3.1 Con—Age: 50.1 ± 2.9 | Tai Chi Quan | Perimenopause | A 24-style simplified form of TC was selected for the TC group. The TC exercises have a fixed voice prompt, including 24 movements (∼5 min is consumed to complete the exercise), and each movement completion time is fixed, for which the exercise rate is fixed. | The cadence of the BW group was not <90 steps/minute (4.8 km/h). The exercise intensity was based on that used in a previous study | 60 | 3 | 48 | 6 |

| Qin, 2002 [51] | CT | Tai Chi—N: 16 Con—N: 15 Tai Chi—Age: 54.1 ± 3.7 Con—Age: 53.8 ± 3.6 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | The Tai Chi Chuan exercisers committed to continue their regular exercise for at least 3.5 h/wk in the 12 months after the baseline measurements and to undergo monitoring of their compliance. | The non-exercising controls did not participate in any physical exercise. | 70 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Wayne, 2012 [52] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 26 Con—N: 43 Tai Chi—Age: 60.4 ± 5.3 Con—Age: 59.1 ± 4.9 | Tai Chi Quan | Postmenopause | Participants in the TC group received nine months of TC training in addition to usual care. They were asked to practice an additional two times per week during the first month, and three times per week thereafter, which could be home practice or additional classes at their school. | Not participating in sports activities and maintaining normal lifestyle habits. | 45 | 4 | 39.1 | 9 |

| Xiao, 2015 [16] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 20 Con—N: 20 Age: 55.5 | Tai Chi Rouli ball | Perimenopause | The Tai Chi group practiced Tai Chi Rouli ball for 6 months. | The control group received no intervention. | 90 | 3 | 26 | 6 |

| Xin, 2024 [50] | RCT | Tai Chi—N: 27 Con—N: 25 Tai Chi—Age: 51.15 ± 3.32 Con—Age: 50.93 ± 3.66 | Tai Chi Rouli ball | Perimenopause | Participants in the Tai Chi Rouli Ball group engaged in the exercise regimen three times a week for a period of six months. Intensity: moderate (was quantitatively assessed using the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion scale). | The control group kept weekly self-reported physical activity diaries, which were used to monitor any major changes in their usual routines that might influence the study outcomes. | 60 | 3 | 26 | 6 |

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

References

- Eastell, R.; O’Neill, T.W.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Langdahl, B.; Reid, I.R.; Gold, D.T.; Cummings, S.R. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.T.; Pavlovic, J.; Fanning, K.M.; Buse, D.C.; Reed, M.L.; Lipton, R.B. Perimenopause and Menopause Are Associated with High Frequency Headache in Women with Migraine: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache 2016, 56, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.J.; Wu, C.M.; Liang, W.N.; Shen, J.Y.; Zhuo, Z.W.; Hu, L.; Ruan, L.W.; Zhang, P.H.; Ye, X.R.; Xu, L.Q.; et al. An Effective Treatment of Perimenopausal Syndrome by Combining Two Traditional Prescriptions of Chinese Botanical Drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 744409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, A.; Ruppert, K.M.; Greendale, G.A.; Lian, Y.J.; Cauley, J.A.; Burnett-Bowie, S.A.; Karvonen-Guttierez, C.; Karlamangla, A.S. Associations of Age at Menopause with Postmenopausal Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk in Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, E561–E569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauley, J.A. Estrogen and bone health in men and women. Steroids 2015, 99, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, R.L.; Oster, G.; Grauer, A.; Crittenden, D.B.; Weycker, D. Determinants of imminent fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, N.C.; Looker, A.C.; Saag, K.G.; Curtis, J.R.; Delzell, E.S.; Randall, S.; Dawson-Hughes, B. The Recent Prevalence of Osteoporosis and Low Bone Mass in the United States Based on Bone Mineral Density at the Femoral Neck or Lumbar Spine. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 2520–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulkar, J.; Singh, S.; Sharma, S.; Thulkar, T. Preventable risk factors for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Midlife Health 2016, 7, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippuner, K.; Johansson, H.; Kanis, J.A.; Rizzoli, R. Remaining lifetime and absolute 10-year probabilities of osteoporotic fracture in Swiss men and women. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Winzenberg, T.M.; Chen, M.S.; Jiang, Q.C.; Palmer, A.J. Residual lifetime and 10 year absolute risks of osteoporotic fractures in Chinese men and women. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2015, 31, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheng, L. Effect of different frequency of Taichi exercise on bone mineral density of older women. Chin. J. Osteoporos. 2017, 23, 1309–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Jakse, B.; Sekulic, D.; Jakse, B.; Cuk, I.; Sajber, D. Bone health among indoor female athletes and associated factors; a cross-sectional study. Res. Sports Med. 2020, 28, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutner, N.G.; Barnhart, H.; Wolf, S.L.; McNeely, E.; Xu, T.S. Self-report benefits of Tai Chi practice by older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Social Sci. 1997, 52, P242–P246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.C.; Wang, W.H.; Chan, P.; Lin, L.J.; Wang, C.H.; Tomlinson, B.; Hsieh, M.H.; Yang, H.Y.; Liu, J.C. The beneficial effects of Tai Chi Chuan on blood pressure and lipid profile and anxiety status in a randomized controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2003, 9, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chang, S.W.; He, B.X.; Yan, Y. Effects of Tai Chi and brisk walking on the bone mineral density of perimenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 948890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.M.; Kang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.C. Effects of Tai Chi Ball on Estrogen Levels, Bone Metabolism Index, and Muscle Strength of Perimenopausal Women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 2629–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.; Qin, L.; Lau, M.C.; Woo, J.; Au, S.; Choy, W.Y.; Lee, K.M.; Lee, S.H. A randomized, prospective study of the effects of Tai Chi Chun exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.; Hong, A.; Lau, E.; Lynn, H. A randomised controlled trial of Tai Chi and resistance exercise on bone health, muscle strength and balance in community-living elderly people. Age Ageing 2007, 36, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Pittler, M.H.; Shin, B.C.; Ernst, E. Tai chi for osteoporosis: A systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 2008, 19, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shan, W.C.; Li, Q.; Yang, N.; Shan, W.Y. Tai Chi Exercise for the Quality of Life in a Perimenopausal Women Organization: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 14, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, P.M.; Kiel, D.P.; Krebs, D.E.; Davis, R.B.; Savetsky-German, J.; Connelly, M.; Buring, J.E. The effects of Tai Chi on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: A systematic review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Chen, H.; Berger, M.R.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Huang, Y. Effects of tai chi exercise on bone health in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 2901–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, P.S.; Liang, Y.J. Effects of mind-body exercise on perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause J. Menopause Soc. 2024, 31, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Jankowski, C.M.; Swanson, C.M.; Hildreth, K.L.; Kohrt, W.M.; Moreau, K.L. Bone Mineral Density in Different Menopause Stages is Associated with Follicle Stimulating Hormone Levels in Healthy Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlamangla, A.S.; Shieh, A.; Greendale, G.A. Hormones and Bone Loss Across the Menopause Transition. In Hormones and Aging; Litwack, G., Ed.; Vitamins and Hormones; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 115, pp. 401–417. [Google Scholar]

- Greendale, G.A.; Sowers, M.; Han, W.J.; Huang, M.H.; Finkelstein, J.S.; Crandall, C.J.; Lee, J.S.; Karlamangla, A.S. Bone mineral density loss in relation to the final menstrual period in a multiethnic cohort: Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlamangla, A.S.; Burnett-Bowie, S.A.M.; Crandall, C.J. Bone Health During the Menopause Transition and Beyond. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J.; Grp, G.W. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Br. Med. J. 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.J.; Page, M.J.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, ED000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Noortgate, W.; López-López, J.A.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Three-level meta-analysis of dependent effect sizes. Behav. Res. Methods 2013, 45, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assink, M.; Wibbelink, C.J. Fitting three-level meta-analytic models in R: A step-by-step tutorial. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2016, 12, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.W.L. A Guide to Conducting a Meta-Analysis with Non-Independent Effect Sizes. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2019, 29, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaffrey, D.F.; Bell, R.M. Bias reduction in standard errors for linear regression with multi-stage samples. Qual. Control Appl. Stat. 2003, 48, 677–682. [Google Scholar]

- Pustejovsky, J.E.; Tipton, E. Meta-analysis with Robust Variance Estimation: Expanding the Range of Working Models. Prev. Sci. 2022, 23, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tipton, E. Small Sample Adjustments for Robust Variance Estimation with Meta-Regression. Psychol. Methods 2015, 20, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2010, 1, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, K.; Noma, H.; Furukawa, T.A. Prediction intervals for random-effects meta-analysis: A confidence distribution approach. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2019, 28, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Noble, D.W.A.; Senior, A.M.; Lagisz, M. Meta-evaluation of meta-analysis: Ten appraisal questions for biologists. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, D.S. A Guide for Calculating Study-Level Statistical Power for Meta-Analyses. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 6, 25152459221147260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Batterham, A.M. Improving Meta-analyses in Sport and Exercise. Sportscience 2018, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ Br. Med. J. 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Vist, G.E.; Glasziou, P.; Akl, E.A.; Skoetz, N.; Guyatt, G.H.; The Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group; The Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Completing ‘Summary of Findings’ Tables and Grading the Certainty of the Evidence. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 375–402. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Montori, V.; Akl, E.A.; Djulbegovic, D.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence-study limitations (risk of bias). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Woodcock, J.; Brozek, J.; Helfand, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Glasziou, P.; Jaeschke, R.; Akl, E.A.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence-inconsistency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Ring, D.; Devereaux, P.J.; Montori, V.M.; Freyschuss, B.; Vist, G.; et al. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence-imprecision. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Montori, V.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Atkins, D.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence-publication bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, A.L.; Guo, L.M. The effects of Tai Chi Rouli ball exercise on bone mineral content and bone metabolism indicators in perimenopausal women. J. Clin. Densitom. 2024, 27, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Au, S.; Choy, W.; Leung, P.C.; Neff, M.; Lee, K.; Lau, M.C.; Woo, J.; Chan, K.M. Regular Tai Chi Chuan exercise may retard bone loss in postmenopausal women: A case-control study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, P.M.; Kiel, D.P.; Buring, J.E.; Connors, E.M.; Bonato, P.; Yeh, G.Y.; Cohen, C.J.; Mancinelli, C.; Davis, R.B. Impact of Tai Chi exercise on multiple fracture-related risk factors in post-menopausal osteopenic women: A pilot pragmatic, randomized trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. The Role of Exercise in Preventing and Treating Lumbar L2-4 Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women. Chin. J. Sports Med. 2003, 22, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan on the changes of bone mineral density of perimenopausal women. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2020, 24, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Jia, J. The Effects of Tai Chi Push Hands Exercise and Calcium Supplementation on Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women. Chin. J. Sports Med. 2005, 24, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhang, M.; Gou, B.; Lv, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H. Influence of Taiji Softball on Estrogen and Bone Metabolism Index of perimenopausal period Women. J. Xi’an Phys. Educ. Univ. 2014, 31, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, X. Effects of Tai Chi on Bone Mineral Density and Bone Metabolism of Postmenopausal Women. Contemp. Sports Technol. 2021, 11, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Study on the Effect of Tai Chi Exercise on Bone Metabolism Indicators in Postmenopausal Women. In Proceedings of the 1st National Wushu Sports Conference and Wushu Science Conference, Tianjin, China, 7 August 2014; pp. 246–249. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H. Effects of taijiquan exercises combined with orally calcium supplement on postmenopausal women’s bone mineral density. Chin. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 24, 814–816. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. The Effects of Enhanced Exercise and Vitamin D Supplement Combined with Calcium on Muscle Strength, Fracture and Life Quality of Postmenopausal Women in Dongcheng District of Beijing. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F. Effects of 24—Form Simplified Tai Chi on Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2017, 33, 1428–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. The Effect of Traditional Sports on Bone Density of Menopause Women. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2004, 354–355+360. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D.; Johnell, O.; Wedel, H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. Br. Med. J. 1996, 312, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.D.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.Z.; Feng, Z.S. Tai Chi for fall prevention and balance improvement in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1236050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, N.Y.; Li, J.X. Biomechanics analysis of seven Tai Chi movements. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2022, 4, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, H.M. From Wolff’s law to the mechanostat: A new “face” of physiology. J. Orthop. Sci. 1998, 3, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenau, E. From mechanostat theory to development of the “Functional Muscle-Bone-Unit”. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2005, 5, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.L.; Wu, J.N.; Guo, J.M.; Zou, D.C.; Chen, B.L.; Sun, Z.G.; Shen, C.; Zou, J. The roles of exercise in bone remodeling and in prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Progress Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2016, 122, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Castillo, N.; Kim-Weroha, N.A.; Kamel, M.A.; Javaheri, B.; Ellies, D.L.; Krumlauf, R.E.; Thiagarajan, G.; Johnson, M.L. In vivo mechanical loading rapidly activates β-catenin signaling in osteocytes through a prostaglandin mediated mechanism. Bone 2015, 76, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.L.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.Q.; Zhang, H. Exercise for osteoporosis: A literature review of pathology and mechanism. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1005665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, D.D.; Latini, A. Exercise-induced immune system response: Anti-inflammatory status on peripheral and central organs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira Kulak, C.A.; Schussheim, D.H.; McMahon, D.J.; Kurland, E.; Silverberg, S.J.; Siris, E.S.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Shane, E. Osteoporosis and low bone mass in premenopausal and perimenopausal women. Endocr. Pract. 2000, 6, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, V.; Morgan, E.F. Estrogen and estrogen receptors mediate the mechanobiology of bone disease and repair. Bone 2024, 188, 117220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, Z.; Fang, Q. Taichi softball as a novel Chinese health-promoting exercise for physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open J. Prev. Med. 2017, 7, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggatt, L.J.; Partridge, N.C. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Bone Remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25103–25108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.B.; Jiang, C.Z.; Fan, R.; Liu, T.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Zhong, D.L.; Zhou, L.X.; Liu, T.; Li, J.; Jin, R.J. The effect and safety of Tai Chi on bone health in postmenopausal women: A meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 935326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.B.; Gong, H.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Cen, H.P.; Fan, Y.B. Biomechanical effects of typical lower limb movements of Chen-style Tai Chi on knee joint. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2023, 61, 3087–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.T.; Chang, J.H.; Huang, C.F. Ground reaction force characteristics of Tai Chi push hand. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1698–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, S.D.; Gass, M.; Hall, J.E.; Lobo, R.; Maki, P.; Rebar, R.W.; Sherman, S.; Sluss, P.M.; de Villiers, T.J.; Grp, S.C. Executive Summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop+10: Addressing the Unfinished Agenda of Staging Reproductive Aging. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, G.E.; Burger, H.G. Hormonal changes and biomarkers in late reproductive age, menopausal transition and menopause. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009, 23, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.B. Fundamentals and pitfalls of bone densitometry using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Osteoporos. Int. 2004, 15, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Mercer, V.S.; Li, F.Z.; Gross, M.T.; Blackburn, T.; Yu, B. The effect of Tai Chi lower extremity exercise on the balance control of older adults in assistant living communities. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedert, A.; Kaspar, D.; Augat, P.; Ignatius, A.; Claes, L. Mechanobiology of Bone Tissue and Bone Cells. In Mechanosensitivity in Cells and Tissues; Kamkin, A., Kiseleva, I., Eds.; Academia Publishing House Ltd.: Moscow, Russia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Manolagas, S.C. Wnt signaling and osteoporosis. Maturitas 2014, 78, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniszczuk, A.; Kaczmarek, A.; Kaczmarek, M.; Cialowicz, M.; Arslan, E.; Silva, A.F.; Clemente, F.M.; Murawska-Cialowicz, E. Sclerostin as a biomarker of physical exercise in osteoporosis: A narrative review. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 954895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Sale, C. Exercise and bone health across the lifespan. Biogerontology 2017, 18, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouvelioti, R.; Kurgan, N.; Falk, B.; Ward, W.E.; Josse, A.R.; Klentrou, P. Response of Sclerostin and Bone Turnover Markers to High Intensity Interval Exercise in Young Women: Does Impact Matter? Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4864952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.; Holloway, L.; Block, G.; Spiller, G.; Gildengorin, G.; Gunderson, E.; Butterfield, G.; Marcus, R. Long-term effects of nutrient intervention on markers of bone remodeling and calciotropic hormones in late-postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemant, J.; Accarie, C.; Peres, G.; Guillemant, S. Acute effects of an oral calcium load on markers of bone metabolism during endurance cycling exercise in male athletes. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2004, 74, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartibian, B.; Maleki, B.H.; Kanaley, J.; Sadeghi, K. Long-term aerobic exercise and omega-3 supplementation modulate osteoporosis through inflammatory mechanisms in post-menopausal women: A randomized, repeated measures study. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvelioti, R.; Kurgan, N.; Falk, B.; Ward, W.E.; Josse, A.R.; Klentrou, P. Cytokine and Sclerostin Response to High-Intensity Interval Running versus Cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2458–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H.; Li, X.; He, Q.; Wang, X.Q. Effects of exercise on bone metabolism in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1597046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainionpää, A.; Korpelainen, R.; Väänänen, H.K.; Haapalahti, J.; Jämsä, T.; Leppäluoto, J. Effect of impact exercise on bone metabolism. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohouli, M.H.; Wang, S.C.; Almuqayyid, F.; Gabiatti, M.P.; Mozaffari, F.; Mohamadian, Z.; Koushki, N.; Alras, K.A.; AlHossan, A.M.; Albatati, S.K.; et al. Impact of vitamin D supplementation on markers of bone turnover: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e14038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemar, S.S.; Dahl, S.S.; West, A.S.; Simonsen, S.A.; Iversen, H.K.; Jorgensen, N.R. A Systematic Review of the Circadian Rhythm of Bone Markers in Blood. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2023, 112, 126–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurban, C.V.; Balas, M.O.; Vlad, M.M.; Caraba, A.E.; Jianu, A.M.; Bernad, E.S.; Borza, C.; Banicioiu-Covei, S.; Motoc, A.G.M. Bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis and their correlation with bone mineral density and menopause duration. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2019, 60, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| P | Menopausal women, including perimenopausal (<12 months since last menstruation) and postmenopausal (≥12 months since last menstruation), with no restriction on age or occupation. | Non-menopausal women; men |

| I | Tai Chi exercise | Non–Tai Chi interventions |

| C | Usual physical activity was defined as maintaining habitual daily routines without structured exercise training, encompassing unavoidable low-intensity aerobic activities (e.g., walking, household chores). | Studies without control groups or with high-intensity exercise as control. |

| O | Bone health outcomes in any body part, including: ① Bone Mineral Density (BMD, assessed by DXA at lumbar spine, femoral neck, etc.) ② Bone Mineral Content (BMC, absolute mineral content) ③ Bone mineral metabolism (BMM, e.g., serum calcium, phosphate, vitamin D, PTH) ④ Bone Turnover Markers (BTMs, e.g., osteocalcin, CTX, P1NP) | No bone health–related outcomes |

| S | Randomized control trials or control trails | Qualitative studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, study protocols, gray literature, or conference abstracts |

| Subgroup | K(N) | Hedges’g | 95%CI | T-Value | Pd | I2-2 | I2-3 | Power | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menopause Stage | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Perimenopause | 34 (1616) | 0.53 | [0.35, 0.71] | 5.97 | <0.01 | 0% | 49.62% | 99% | |

| Postmenopause | 44 (2716) | 0.22 | [0.06, 0.37] | 2.83 | 0.01 | 30.16% | 0% | 83% | |

| Body Part | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Calcanei | 1 (52) | 0.25 | [−0.39, 0.89] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Femoral neck | 11 (682) | 0.37 | [0.14, 0.59] | 3.30 | <0.01 | 72.44% | 0% | 92% | |

| Greater trochanter | 10 (613) | 0.33 | [0.10, 0.56] | 2.90 | <0.01 | 41.19% | 0% | 85% | |

| Pelvis | 2 (82) | −0.01 | [−0.51, 0.50] | −0.03 | 0.98 | 13.40% | 13.4% | 5% | |

| Spine L2–L4 | 23 (1280) | 0.47 | [0.28, 0.65] | 4.94 | <0.01 | 51.99% | 0% | 99% | |

| Thigh | 5 (323) | 0.32 | [0.04, 0.60] | 2.27 | 0.03 | 9.83% | 0% | 63% | |

| Tibia | 4 (124) | 0.33 | [−0.16, 0.82] | 1.34 | 0.18 | 0% | 0% | 28% | |

| Trunk | 2 (82) | 0.96 | [0.42, 1.49] | 3.56 | <0.01 | 0% | 0% | 94% | |

| Upper limb | 9 (502) | 0.29 | [0.03, 0.56] | 2.11 | 0.03 | 3.64% | 0% | 61% | |

| Ward’s triangle | 9 (510) | 0.27 | [0.03, 0.51] | 2.23 | 0.03 | 21.75% | 0% | 61% | |

| Whole body | 2 (82) | −0.32 | [−0.83, 0.19] | −1.23 | 0.22 | 40.91% | 40.91% | 23% | |

| Taichi Type | 0.12 | ||||||||

| Tai Chi chuan | 55 (3472) | 0.27 | [0.11, 0.43] | 3.45 | <0.01 | 37.52% | 0% | 93% | |

| Tai Chi Push Hands | 5 (128) | 0.33 | [−0.08, 0.74] | 1.59 | 0.12 | 0% | 0% | 36% | |

| Taichi rouli ball | 18 (732) | 0.60 | [0.33, 0.87] | 4.42 | <0.01 | 0% | 63.33% | 99% |

| Body Part | Menopausal Stage | Predicted SMD | 95%CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limb | Perimenopause | 0.26 | [−0.24, 0.77] | 0.31 |

| Postmenopause | 0.20 | [−0.07, 0.48] | 0.15 | |

| Ward triangle | Perimenopause | 0.43 | [0.11, 0.75] | 0.01 |

| Postmenopause | 0.18 | [−0.12, 0.49] | 0.25 | |

| Greater trochanter | Perimenopause | 0.61 | [0.28, 0.93] | <0.01 |

| Postmenopause | 0.15 | [−0.12, 0.41] | 0.28 | |

| Femoral neck | Perimenopause | 0.50 | [0.17, 0.82] | <0.01 |

| Postmenopause | 0.28 | [0.03, 0.53] | 0.03 | |

| Spine L2–L4 | Perimenopause | 0.81 | [0.54, 1.08] | <0.01 |

| Postmenopause | 0.25 | [0.05, 0.46] | 0.02 |

| Subgroup | K(N) | Hedges’g | 95%CI | T-Value | Pd | I2-2 | I2-3 | Power | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Part | 0.58 | ||||||||

| Hip | 3 (120) | 2.60 | [0.25, 4.94] | 2.44 | 0.03 | 0% | 96.57% | 69% | |

| Pelvis | 2 (82) | 0.79 | [−1.51, 3.08] | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0% | 0% | 12% | |

| Spine L2–L4 | 5 (202) | 2.00 | [0.11, 3.89] | 2.33 | 0.04 | 94.75% | 0% | 64% | |

| Thigh | 2 (82) | 0.56 | [−1.73, 2.85] | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0% | 0% | 8% | |

| Trunk | 2 (82) | 1.32 | [−0.98, 3.63] | 1.26 | 0.23 | 0% | 0% | 24% | |

| upper limb | 2 (82) | 2.00 | [−0.33, 4.33] | 1.89 | 0.09 | 0% | 0% | 47% | |

| whole body | 2 (82) | 0.57 | [−1.72, 2.87] | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0% | 0% | 8% | |

| Duration | 0.53 | ||||||||

| 60 min | 6 (312) | 1.95 | [0.84, 3.07] | 3.72 | <0.01 | 0% | 87.81% | 96% | |

| 90 min | 12 (420) | 1.54 | [0.74, 2.34] | 4.08 | <0.01 | 0% | 91.08% | 98% | |

| Frequency | 0.81 | ||||||||

| <4 times per week | 12 (180) | 1.63 | [0.82, 2.43] | 4.29 | <0.01 | 0% | 93.85% | 99% | |

| >4 times per week | 6 (552) | 1.79 | [0.64, 2.94] | 3.29 | <0.01 | 0% | 50.63% | 91% |

| Subgroup | K(N) | Hedges’g | 95%CI | T-Value | Pd | I2-2 | I2-3 | Power | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menopause Stage | 0.53 | ||||||||

| Perimenopause | 6 (246) | −4.79 | [−15.63, 6.05] | −1.08 | 0.32 | 90.80% | 8.22% | 19% | |

| Postmenopause | 2 (78) | −0.48 | [−11.86, 10.90] | −0.10 | 0.92 | 36.81% | 36.81% | 5% | |

| Duration | 0.46 | ||||||||

| 60 min | 5 (234) | −4.20 | [−13.01, 4.62] | −1.16 | 0.29 | 69.08% | 29.02% | 21% | |

| 90 min | 3 (90) | 1.28 | [−13.42, 15.98] | 0.21 | 0.84 | 0% | 72.58% | 6% | |

| Frequency | 0.32 | ||||||||

| <4 times per week | 4 (116) | −5.80 | [−15.43, 3.83] | −1.47 | 0.19 | 76.43% | 21.99% | 31% | |

| >4 times per week | 4 (208) | 0.23 | [−9.38, 9.84] | 0.06 | 0.95 | 77.23% | 16.34% | 5% |

| Subgroup | K(N) | Hedges’g | 95%CI | T-Value | Pd | I2-2 | I2-3 | Power | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menopause Stage | 0.92 | ||||||||

| Perimenopause | 4 (162) | −0.14 | [−0.53, 0.24] | −0.83 | 0.43 | 0% | 0% | 22% | |

| Postmenopause | 8 (982) | −0.12 | [−0.35, 0.10] | −1.22 | 0.25 | 32.69% | 1.31% | 13% | |

| Duration | 0.78 | ||||||||

| <45 min | 4 (826) | −0.11 | [−0.39, 0.18] | −0.84 | 0.42 | 27.46% | 5.27% | 13% | |

| >45 min | 8 (318) | −0.16 | [−0.45, 0.13] | −1.23 | 0.25 | 16.02% | 0.00% | 23% | |

| Period | 0.07 | ||||||||

| <1 year | 8 (352) | −0.27 | [−0.52, −0.03] | −2.51 | 0.03 | 0% | 0% | 71% | |

| >1 year | 4 (792) | −0.01 | [−0.16, 0.15] | −0.06 | 0.96 | 0% | 5% | 5% | |

| Frequency | 0.28 | ||||||||

| <4 times per week | 5 (236) | −0.04 | [−0.35, 0.28] | −0.26 | 0.80 | 0% | 0% | 5% | |

| =4 times per week | 4 (826) | −0.08 | [−0.30, 0.13] | −0.89 | 0.40 | 27.46% | 5.27% | 14% | |

| >4 times per week | 3 (82) | −0.49 | [−1.02, 0.05] | −2.06 | 0.07 | 16.21% | 0.00% | 54% |

| Author Year | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | D10 | D11 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xin 2024 [50] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Qin 2002 [51] | Y | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Wayne 2012 [52] | Y | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Xiao 2015 [16] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Cheng 2022 [15] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Chan 2004 [17] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Zhou 2003 [53] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Zhou 2004 [62] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Zhou 2005 [55] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Zhao 2020 [54] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Du 2014 [56] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Liu 2021 [57] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Guo 2014 [58] | Y | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Mao 2009 [59] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Xue 2015 [60] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Xu 2017 [61] | Y | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Outcome | No. of Participants (Studies) | Certainty Assessment | Effect Size (SMD [95% CI]) | Certainty (GRADE) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Other | ||||

| Bone Mineral Density | 700 (14) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 0.31 [0.16, 0.45] | Moderate |

| Bone Mineral Content | 122 (3) | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Large Effect Size | 1.63 [0.64, 2.62] | Low |

| Bone Mineral Metabolism | 160 (4) | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Large Effect Size | −2.71 [−12.00, −6.59] | Low |

| Bone Turnover Markers | 613 (7) | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | −0.10 [−0.35, 0.16] | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, W.; Zeng, Z.; Yin, W.; Xi, L.; Wu, D.; Qiao, F. Tai Chi Exercise and Bone Health in Women at Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Stages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111678

Yin W, Zeng Z, Yin W, Xi L, Wu D, Qiao F. Tai Chi Exercise and Bone Health in Women at Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Stages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life. 2025; 15(11):1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111678

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Wenhui, Zhuo Zeng, Wenyan Yin, Long Xi, Dong Wu, and Fengjie Qiao. 2025. "Tai Chi Exercise and Bone Health in Women at Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Stages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Life 15, no. 11: 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111678

APA StyleYin, W., Zeng, Z., Yin, W., Xi, L., Wu, D., & Qiao, F. (2025). Tai Chi Exercise and Bone Health in Women at Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Stages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life, 15(11), 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111678