1. Introduction

Milling is one of the most widely used and important machining processes in modern industries, including aerospace, automotive, and medical device manufacturing [

1,

2]. It uses a rotating cutting tool to remove material from a workpiece and can create flat surfaces, grooves, threads, and complex shapes with high precision [

3]. Due to its high efficiency and flexibility, milling plays an important role in both small workshops and large factories [

4]. However, during milling operations, tools are exposed to high forces, frictional heat, and constant vibrations [

5]. These conditions eventually cause the tool to wear out or, in some cases, break suddenly [

6]. Tool wear not only reduces product quality but also causes surface roughness, dimensional errors, and unplanned machine stoppages, which increase production costs. Studies show that tool-related failures are responsible for 7–20% of total machine downtime, and tool costs can contribute up to 12% of the overall manufacturing budget [

7,

8]. In most factories, tools are replaced based on fixed time intervals or operator experience [

9]. This approach is not always reliable. Sometimes tools are changed too early, wasting usable life, and other times too late, leading to failure. On average, only 50–80% of a tool’s actual life is utilized [

10,

11]. To solve this problem, Tool Condition Monitoring (TCM) systems are being used to monitor tool health in real time and provide early warnings before failure occurs [

12,

13]. There are two main types of TCM methods: direct and indirect. Direct methods involve using cameras or microscopes to inspect the tool’s surface, but they are expensive and difficult to use in real production settings [

14,

15]. Indirect methods are more practical and are widely used in the industry [

16]. They rely on signals such as vibration, cutting forces, spindle current, and acoustic emission (AE) [

17]; among these, AE signals are particularly popular [

18]. AE signals are high-frequency sound waves produced when cracks form, friction occurs, or deformation happens during cutting, making them very useful for detecting early tool damage [

19]. However, AE signals are complex and often affected by changes in cutting speed, tool material, and machine settings, making them difficult to analyze [

20]. To process these signals, researchers use techniques such as time-domain statistics, frequency analysis, wavelet transforms, or empirical mode decomposition to extract features [

21]. These features are then classified using machine learning models such as Support Vector Machines, Hidden Markov Models, and Artificial Neural Networks [

22,

23]. While effective, these methods depend heavily on manual feature extraction and do not perform well when the amount of labeled data is small or when the operating conditions vary significantly [

24].

In recent years, deep learning has helped improve fault diagnosis in TCM [

25,

26]. Models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

27], Recurrent Neural Networks, and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory networks can automatically learn patterns from raw data [

28,

29]. A popular method is to convert AE signals into 2D images called scalograms using the Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT). These scalograms show both time and frequency information, making it easier for deep learning models to detect tool defect patterns [

30]. Deep learning has also been used with traditional physical models and sensor fusion to improve performance [

31,

32]. However, deep learning requires a large amount of labeled data to work effectively [

33]. In real-world applications, especially for rare fault types, collecting large datasets is difficult and expensive [

34]. When data is limited, deep models often become unreliable and may not generalize well [

35]. Deep learning can find useful patterns on its own, but it needs a lot of labeled data. In the circumstances where labeled data are scarce, Few-Shot Learning (FSL) becomes a better option [

36]. FSL is a type of learning that allows models to recognize new fault types using only a few labeled instances. For instance, Li et al. [

37] proposed a method that improves fault classification by separating different classes and keeping samples from the same class close together. Liang et al. [

38] reviewed different FSL techniques and found that meta-learning and attention mechanisms are especially useful for fault diagnosis. Wang et al. [

39] introduced a meta-learning model that can adapt to new working conditions even with limited training data. More recently, researchers have developed a model that combines prototype refinement with contrastive learning, helping the system distinguish between very similar faults [

40]. These methods have shown great potential, but many of them still require complicated training procedures, high computing resources, and often do not fully utilize attention mechanisms or adaptive class representations [

41]. Additionally, very few of these studies focus on milling tools using AE signals [

42].

To overcome these challenges, this study proposes an improved Few-Shot Learning framework for diagnosing faults in milling cutting tools using AE signals. In the current method, raw AE signals are transformed into two-dimensional scalograms using the CWT to capture time–frequency characteristics. A deep learning model based on ResNet-50, augmented with spatial and channel-wise attention mechanisms, is then utilized to emphasize the most informative regions. To enhance fault type discrimination with limited samples, class prototypes are computed using a learnable weighting technique, enabling more accurate class representation. For classification, the Mahalanobis distance is utilized to account for feature distribution. The framework is trained under an episodic learning setup and evaluated on real AE data collected during milling operations. The results show that the proposed method achieves high accuracy, learns better fault representations, and generalizes well across different conditions, even with very little data.

To better emphasize the novelty and advantages of the proposed framework, a comparative summary of representative recent studies is provided in

Table 1. The proposed approach introduces four main innovations: (i) a learnable importance weighting mechanism for adaptive prototype computation; (ii) spatial and channel-wise attention modules integrated within a ResNet-50 backbone to enhance time–frequency feature extraction; (iii) Mahalanobis distance-based prototype-query matching to account for feature distribution; and (iv) contrastive loss with hard negative mining for improved inter-class separation. In comparison to conventional CNNs and LSTMs that require large, labeled datasets, the proposed model achieves high classification accuracy with only five samples per class. Compared with previous FSL learning approaches, the proposed method demonstrates higher robustness and data efficiency, achieving an average accuracy of 98.86% ± 0.97%, outperforming other approaches. These findings confirm that the proposed method offers a reliable, data-efficient, and generalizable solution for intelligent fault diagnosis in milling operations.

The main contributions in this work are as follows.

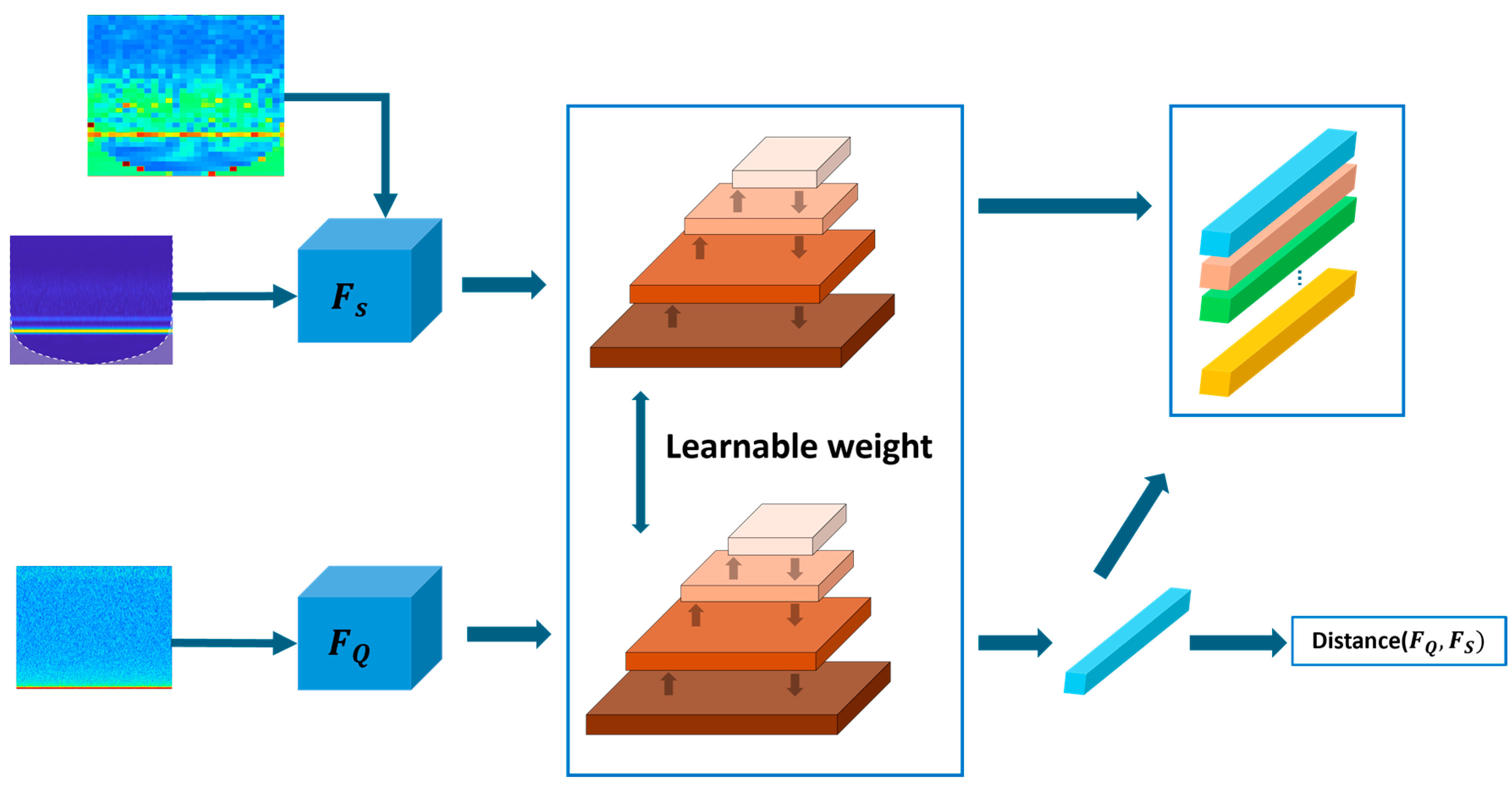

A learnable importance weighting mechanism is introduced for prototype computation, selectively emphasizing discriminative feature dimensions and enhancing class representation in few-shot fault diagnosis.

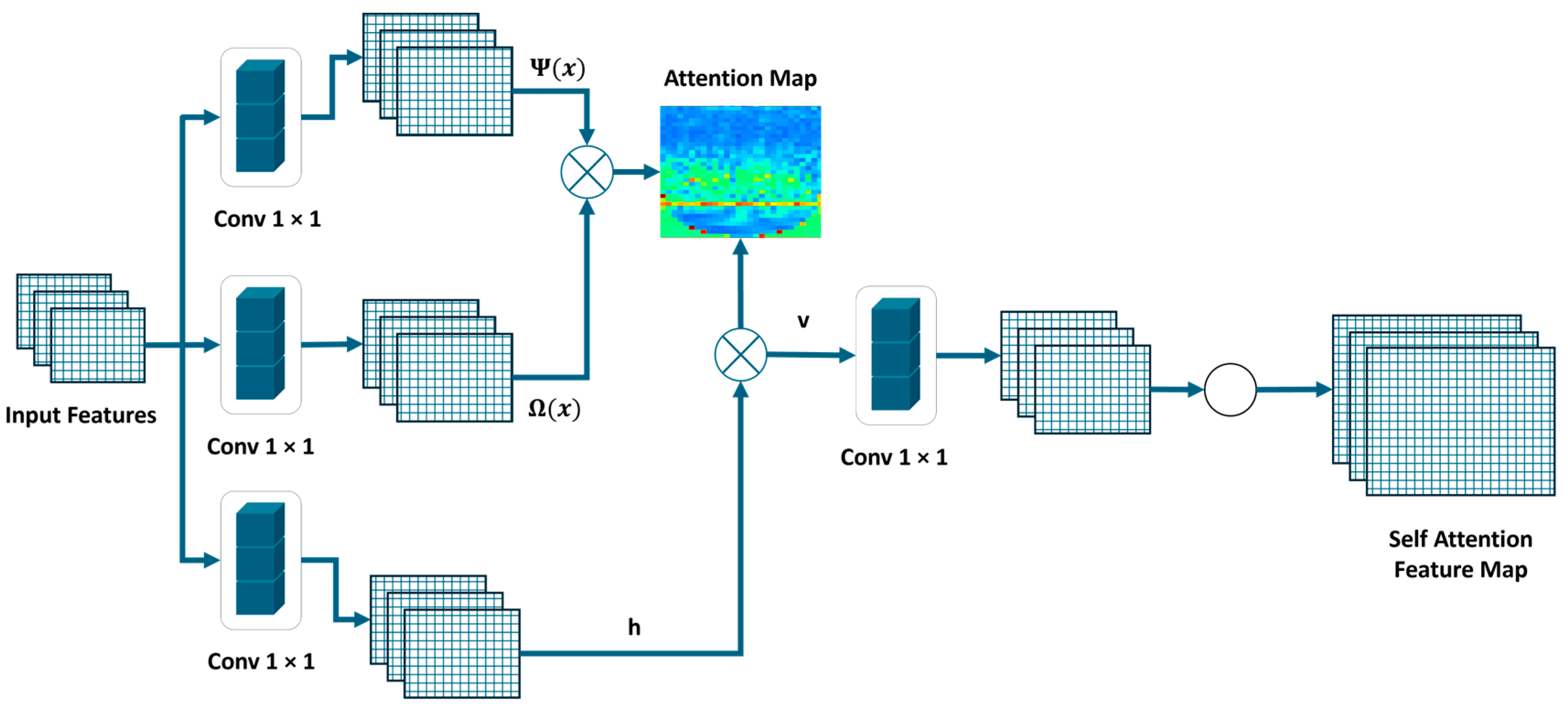

Spatial and channel-wise self-attention modules are integrated into a ResNet-50 backbone, enabling more expressive representation of 2D CWT scalograms by capturing both local textures and global dependencies in fault-related patterns.

Mahalanobis distance with regularized class-wise covariance is employed for prototype-query matching, providing robust similarity measurement under limited-data conditions.

Contrastive loss with hard negative mining is adopted to enforce intra-class compactness and inter-class separability, thereby improving feature clustering and overall generalization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the proposed methodology,

Section 3 outlines the technical background,

Section 4 details the experimental setup,

Section 5 reports the results,

Section 6 provides an in-depth discussion, and

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Proposed Methodology

This section presents the proposed FSL framework for milling machine fault diagnosis, which integrates adaptive prototype computation, self-attention mechanisms, and contrastive loss to achieve robust classification under limited data conditions. The methodology is organized into five major stages: data preprocessing, feature extraction, prototype learning, similarity-based classification, and episodic training. The overall flowchart of the proposed method is illustrated in

Figure 1:

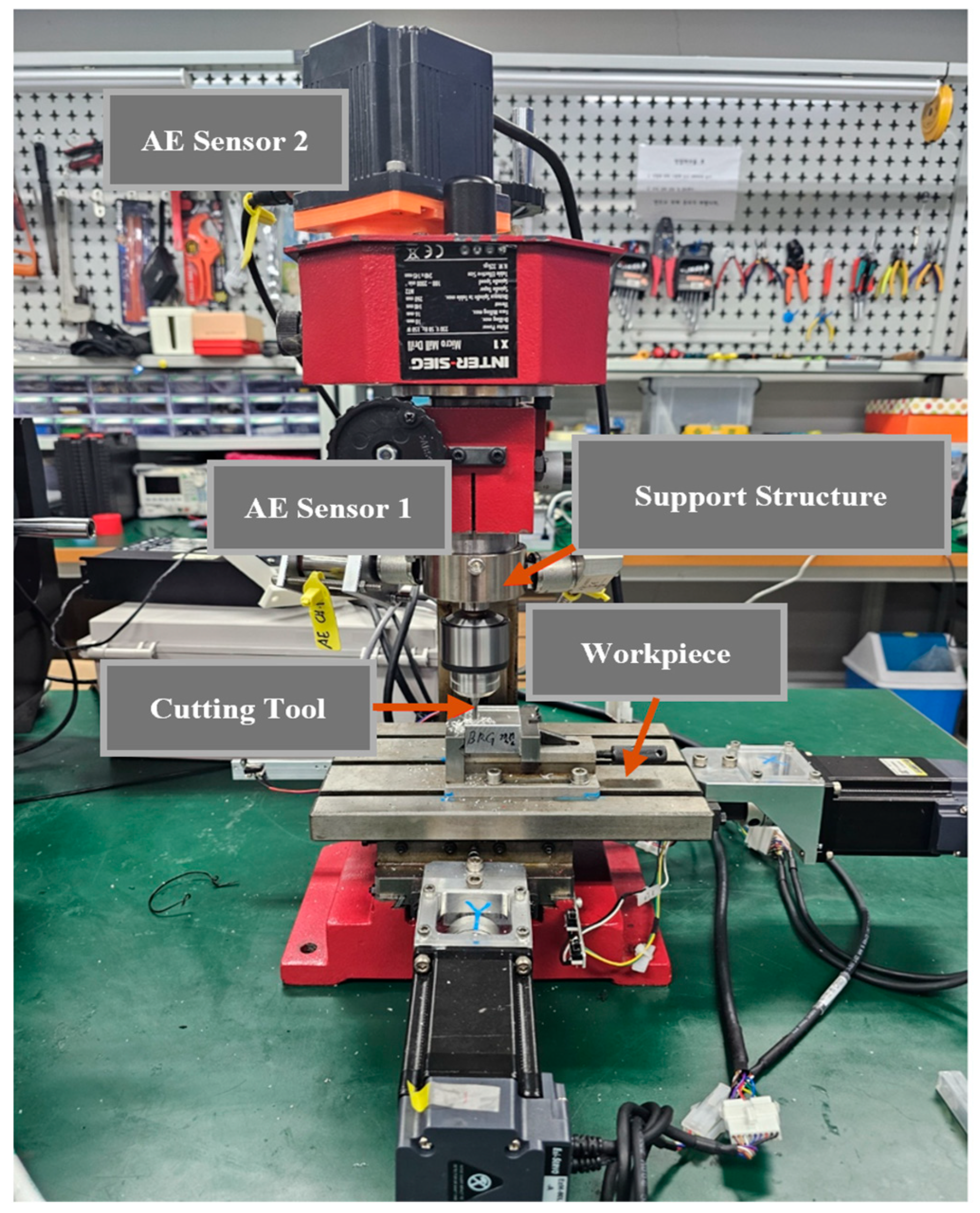

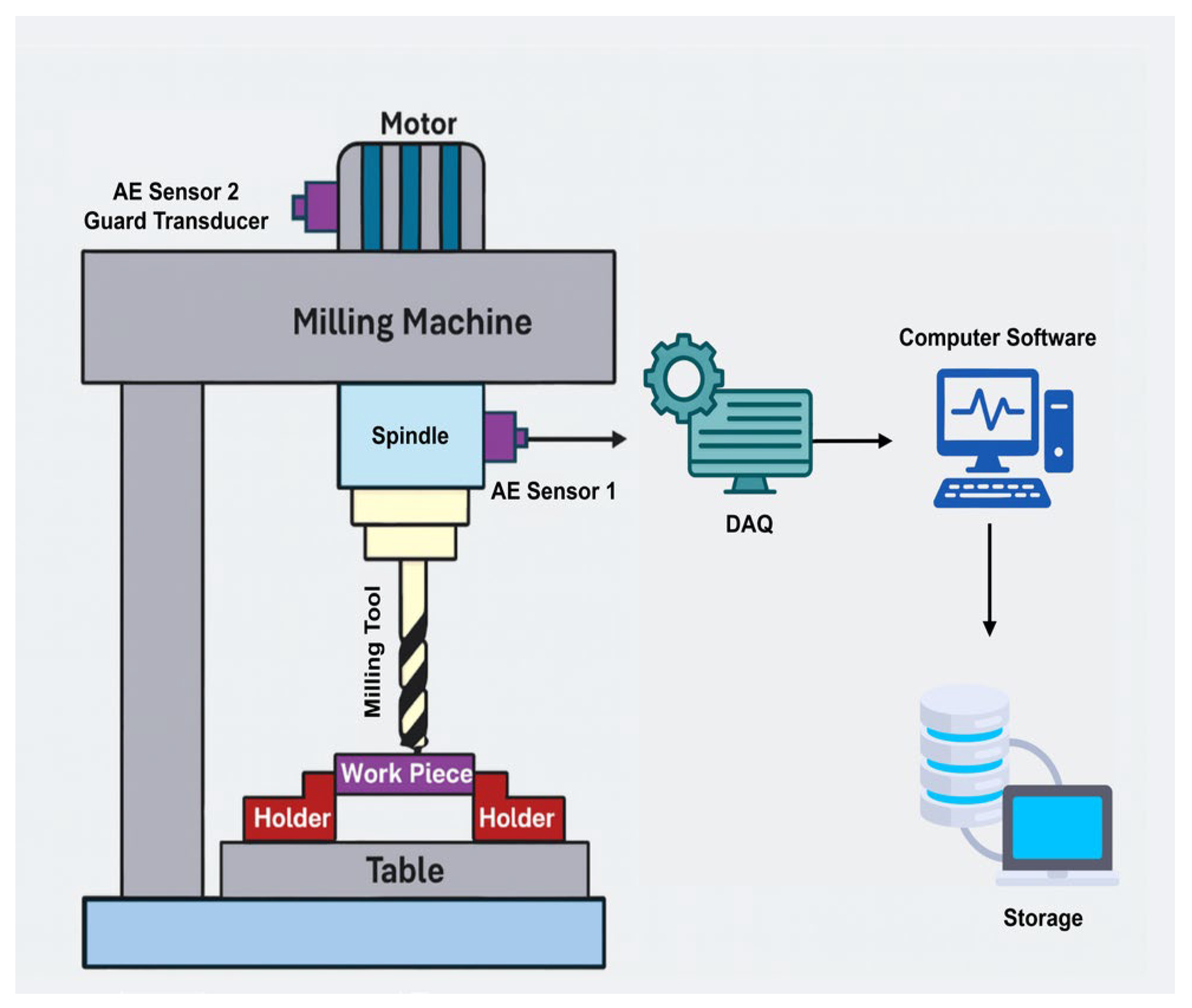

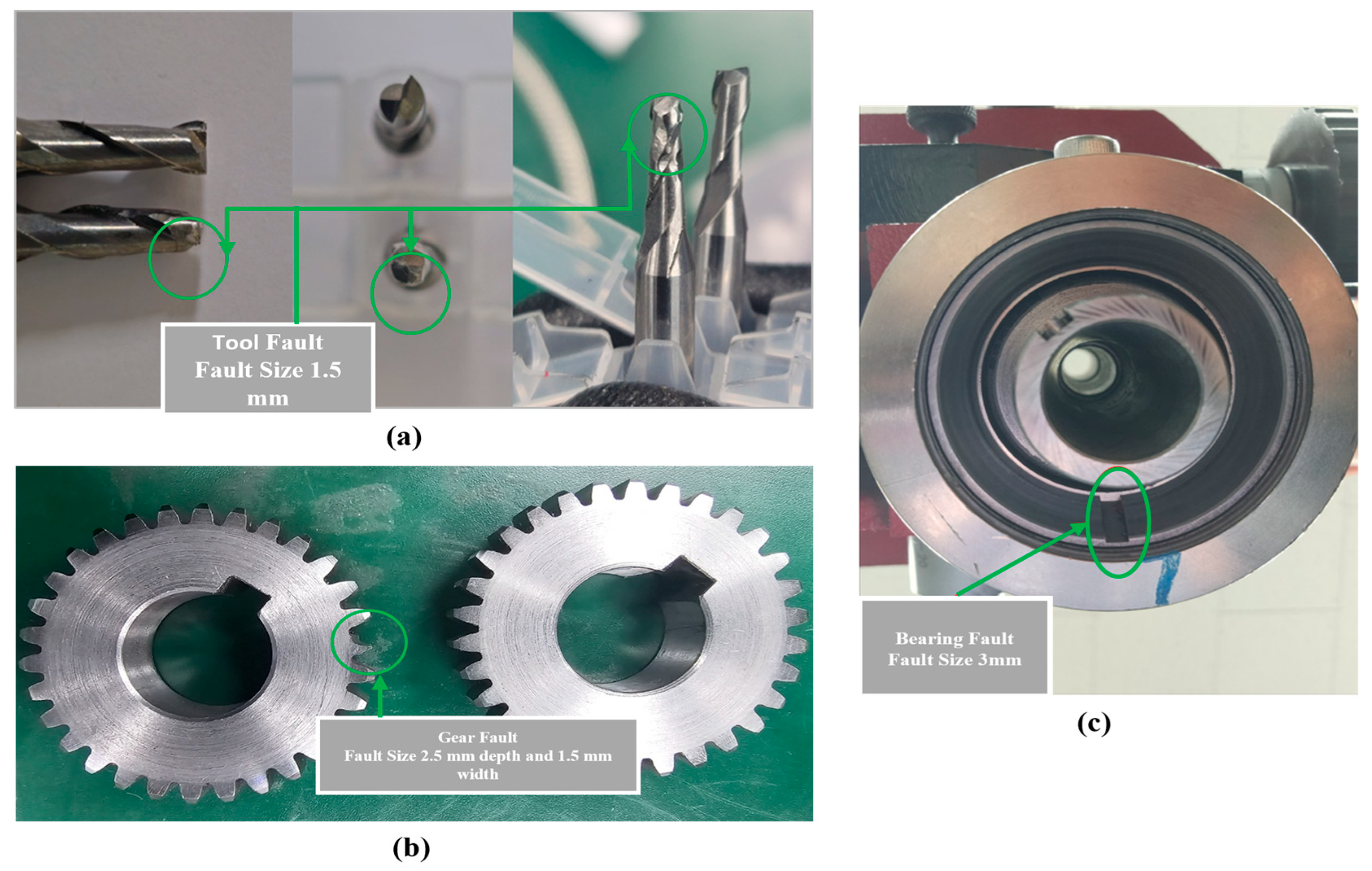

Step I: The dataset used in this study was collected from a milling machine testbed equipped with AE sensors, and signals were acquired under various fault conditions. The system records multi-channel AE signals during machining operations, capturing high-frequency signal patterns. CWT is applied to generate 2D scalograms to capture time–frequency patterns, extracting rich spectral features. Each sample is resized to 224 × 224 × 3 pixels and normalized using min-max scaling to enhance feature representation. Data augmentation techniques, like random cropping, rotation, and small translations, are applied to the scalograms to improve generalization. The dataset is then split into a support set and a query set using a stratified episodic sampling technique to ensure balanced class representation.

Step II: In the second stage, feature extraction is performed using a modified ResNet-50 architecture augmented with attention mechanisms, referred to as Self-Attention ResNet-50 (SA-ResNet50). This backbone incorporates spatial attention to capture local and global contextual dependencies and channel-wise attention to highlight the most discriminative feature maps. This dual-attention design enhances the network’s ability to isolate and represent subtle fault characteristics in the CWT scalograms. The resulting feature embeddings are passed to the prototype learning module.

Step III: The third stage uses an adaptive prototype learning strategy that enhances class representation. Each support sample is encoded with the SA-ResNet50 network to obtain its embedding. For each class, the mean vector of the support embeddings is computed and normalized. The learnable importance of the weight vector is then applied to reweight the feature dimensions of the prototype, emphasizing class-specific discriminative information. This weight vector is optimized jointly with the model parameters through backpropagation, resulting in task-adaptive and expressive prototypes that better capture intra-class characteristics.

Step IV: In the fourth stage, classification of query samples is performed by comparing them to the refined prototypes using the Mahalanobis distance, which incorporates the class-wise covariance matrix to provide more reliable similarity estimates in low-sample conditions. To further improve feature discrimination, a pairwise contrastive loss with hard negative mining is applied. This loss encourages intra-class compactness and inter-class separation in the embedding space, refining the model’s decision boundaries.

Step V: The final stage involves episodic training using a 7-way, 5-shot setting. In each training episode, new support and query sets are dynamically sampled. The model is optimized using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of , and gradient clipping with a maximum norm of 1 is applied to prevent exploding gradients. Model performance is evaluated using standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. To visually assess the clustering quality of the learned representations, t-SNE is used to project high-dimensional embeddings into a two-dimensional space, demonstrating the model’s ability to form well-separated and compact clusters corresponding to different fault classes.

5. Results

This section presents a detailed experimental evaluation of the proposed FSL framework for fault diagnosis in milling machines. The experiments were designed to replicate challenging real-world scenarios where only a limited number of labeled samples are available per fault category. All evaluations were conducted using CWT scalogram images generated from AE signals. To ensure fairness and reproducibility, the same preprocessing pipeline, training strategy, and computational environment were applied to both the proposed model and all comparison architectures. The analysis is structured into three parts: (a) overall classification performance, (b) few-shot generalization, and (c) visualization of learned representations.

The proposed approach was compared against widely used CNN architectures, including ResNet-18, ResNet-50, ShuffleNetV2, MobileNetV3 Large, DenseNet-201, and SqueezeNet. All models were trained using the same preprocessing strategy: images were resized to 224 × 224, normalized to [−1, 1], and augmented using random horizontal flips and slight rotations. Training and evaluation were conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU using PyTorch 2.8.0. Classification performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, specificity, Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC), and training time, as provided in

Table 5. The proposed model achieved 99.32% accuracy, reflecting perfect generalization and better classification performance under data-constrained conditions. In contrast, ResNet-18 achieved 91.43% accuracy, ResNet-50 85.71%, ShuffleNetV2 70.00%, MobileNetV3 84.29%, DenseNet-201 89.29, and SqueezeNet 78.57%. Despite DenseNet-201 requiring over 11 min for training, it still underperformed compared to the proposed lightweight framework, which required only one minute. This highlights the proposed method’s better classification performance and computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-time and resource-limited industrial environments. The high precision and recall values achieved by the proposed framework demonstrate its ability to correctly classify fault conditions while minimizing both false positives and false negatives. These results confirm the model’s strong regularization ability and effective optimization under low-data conditions, with no signs of overfitting. The visual evidence aligns with these quantitative results.

This reliability is further illustrated by the confusion matrix, which shows perfect classification across all operating conditions as shown in

Figure 12a. The training curves of the proposed method further support these findings. The model exhibited a smooth ascent in accuracy and a consistent decline in loss, converging to 100% accuracy with near-zero training loss over 500 epochs, as shown in

Figure 12b,c. Occasional small fluctuations in the loss were attributed to the dynamics of contrastive loss and the episodic sampling strategy, but did not impact convergence stability.

To better understand the distribution and discriminability of the learned features, we plotted t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to visualize high-dimensional embeddings in a two-dimensional space. The resulting plots showed tight intra-class clusters and well-separated inter-class margins as shown in

Figure 12d, indicating the model’s capability to learn highly discriminative feature representations. This improvement can be attributed to the self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to focus on the most informative time–frequency regions in the scalograms, and the contrastive loss function, which reinforces both intra-class compactness and inter-class separation. These insights are supported by the better feature learning capacity of the model’s SA-ResNet50 backbone, which enhances the extraction of meaningful and contextually rich representations.

To further quantify the model’s decision confidence and class discrimination, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted for each class as shown in

Figure 12e. The proposed framework achieved AUC scores close to 1.0 across all fault categories, confirming its high confidence and robustness even in low-data scenarios. These high AUC values validate that the model not only distinguishes between classes with great accuracy but also maintains strong generalization across unseen query samples.

One of the core challenges in industrial fault diagnosis is adapting to conditions with extremely limited labeled samples.

Table 6 presents the classification performance under 1-shot, 3-shot, and 5-shot learning setups. As expected, performance improves steadily with more labeled samples. The 1-shot configuration yielded 87.46% accuracy, sufficient for coarse classification, while the 3-shot setting improved accuracy to 93.18%. With 5 shots, the model achieved 99.32% accuracy, highlighting its ability to generalize even under highly constrained supervision. The proposed framework consistently outperformed conventional CNNs across all evaluations. Its ability to deliver high accuracy under 5-shot settings, adverse feature clustering, and computational efficiency establishes it as a highly practical solution for fault diagnosis in modern manufacturing environments.

To further assess the generalization capability of the proposed method, additional experiments were conducted using datasets collected under two distinct spindle speeds: 1440 rpm and 660 rpm. These conditions were chosen to simulate different cutting environments and evaluate the robustness of the model under variable AE characteristics. The quantitative results for both spindle speeds are summarized in

Table 7. At 1440 rpm, the model achieved an average precision of 97.4%, a recall of 97.2%, and an F1-score of 97.3%, indicating reliable discrimination among tool-wear classes under high-speed conditions. At 660 rpm, all performance metrics exceeded 99.8%, demonstrating the framework’s ability to maintain nearly perfect accuracy under low-speed operation. The model achieved high and balanced classification performance for both the updated and newly collected data. The confusion matrix in

Figure 13a for 660 rpm displays strong diagonal dominance, and the t-SNE visualization in

Figure 13b shows clear separation between all states, indicating that the learned embeddings remain discriminative under high-speed operation. The confusion matrix, as in

Figure 14a for the 1440 rpm, confirms better predictions, and the t-SNE projection in

Figure 14b demonstrates complete separability among the feature clusters. The model achieved high and balanced classification performance for both the updated and newly collected data. The confusion matrix in

Figure 13a for 660 rpm displays strong diagonal dominance, and the t-SNE visualization shows clear separation between all states, indicating that the learned embeddings remain discriminative under high-speed operation. The confusion matrix, as in

Figure 14a for the 1440 rpm, confirms better predictions, and the t-SNE projection in

Figure 14b demonstrates complete separability among the feature clusters. These results clearly indicate that the proposed framework maintains consistent discriminative ability across different spindle speeds. The consistent results across both speed operations validate the robustness and stability of the proposed network and confirm its ability to generalize effectively across diverse machining conditions.

6. Discussion

The integration of Mahalanobis distance into the prototype matching process played a significant role in enhancing classification robustness. Unlike other distances, Mahalanobis distance considers the covariance structure of class-wise features, allowing for more accurate similarity matching, especially in cases involving subtle signal differences. Furthermore, the adaptive prototype learning mechanism dynamically refined class representations during training, improving intra-class consistency and inter-class distinctiveness. These components, working together with contrastive loss, contributed to robust class separability and minimized misclassifications. The proposed model’s strong few-shot learning performance is thus attributed to this combination of adaptive prototype learning, attention-guided representation, and covariance-aware matching, which enables it to generalize effectively even under data scarcity.

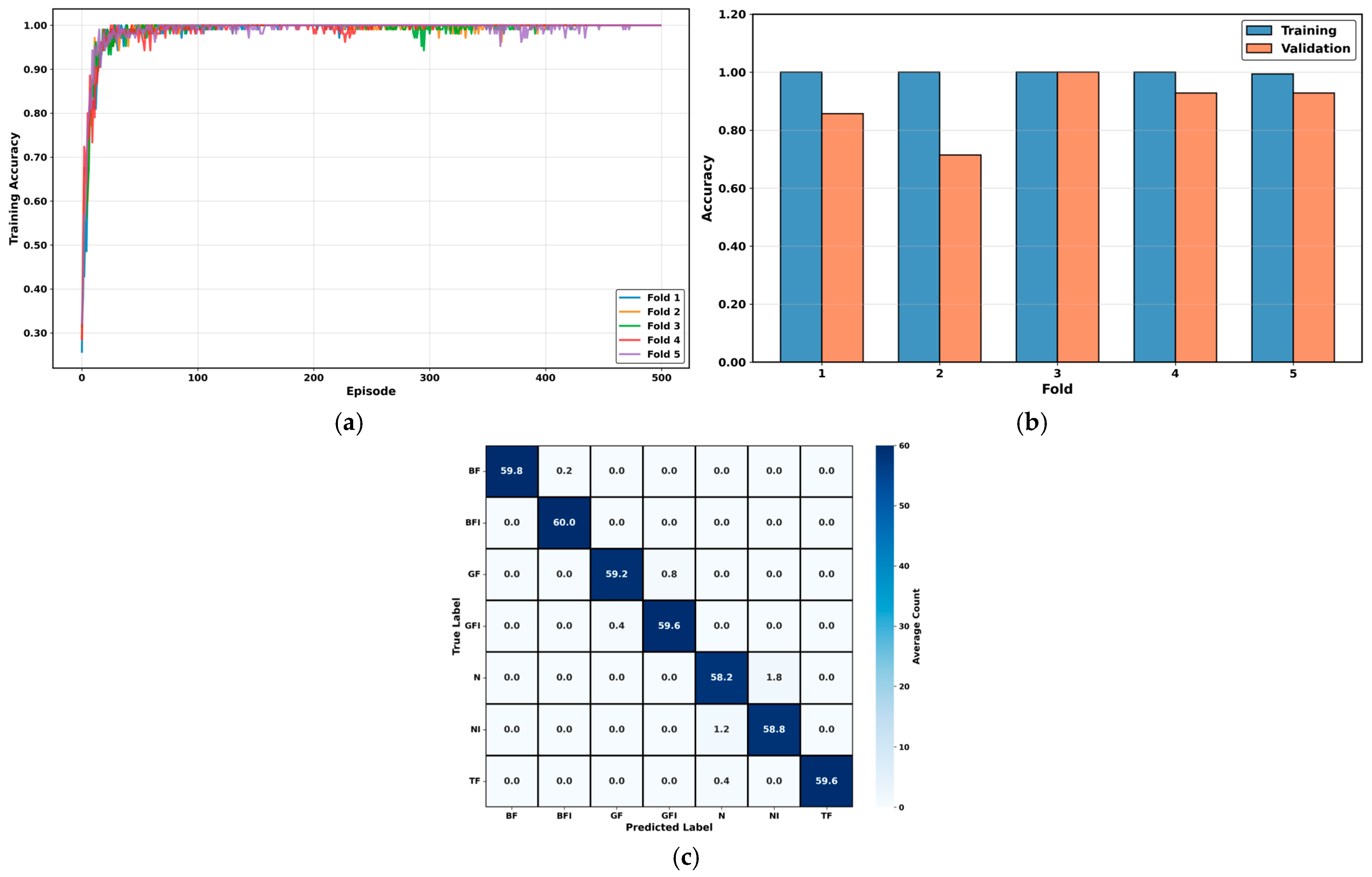

To address concerns regarding overfitting in the proposed method, a comprehensive 5-fold stratified cross-validation was conducted to rigorously evaluate the robustness and generalization. The detailed fold-wise results confirm that the model maintains better consistency across all partitions, with validation accuracy ranging from 97.14% to 100% and a mean accuracy of 98.86% ± 0.97% (95% CI = [98.01%, 99.71%]). The low standard deviation (σ = 0.97%) across folds indicates that the model’s performance is not sensitive to specific train-test splits. The training dynamics illustrated in

Figure 15 a show uniform and stable convergence behavior across all five folds, with each fold achieving rapid convergence within the first 200 episodes. The training-validation comparison shown in

Figure 15b further supports this, as the performance gap remains consistently narrow (≈1% on average) between the training accuracy (99.99% ± 0.02%) and validation accuracy (98.86% ± 0.97%). Such a minimal gap demonstrates effective generalization and indicates that the model learns meaningful prototypical representations. Moreover, the mean confusion matrix in

Figure 15c exhibits pronounced diagonal dominance across all seven conditions, underscoring the model’s discriminative ability and class-level stability. The strong consistency across folds substantiates that the proposed network achieves reliable few-shot learning performance even under constrained data conditions. Although environmental noise and sensor calibration can affect AE data acquisition, the use of the Hsu–Nielsen test and 50–450 kHz band-pass filtering ensured consistent sensor sensitivity and minimized external interference during all experiments.

To further interpret the network’s decision process, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping++ (Grad-CAM++) was applied to visualize the most influential regions within the CWT scalograms.

Figure 16 presents the class-wise average activation maps for all seven fault conditions (BF, BFI, GF, GFI, N, NI, and TF). The red regions indicate higher activation intensity, representing the areas where the model focused during classification. The visualization results show that each fault type activates distinct time–frequency regions, revealing the network’s ability to capture fault-specific acoustic characteristics. For example, severe breakage conditions (BF, TF) show concentrated activations in high-frequency regions associated with impact-type emissions, whereas gradual wear faults (GF, GFI) produce distributed mid-frequency responses. The normal states (N, NI) exhibit low and stable activation areas, corresponding to the absence of sudden AE bursts. These findings confirm that the attention-augmented ResNet backbone effectively emphasizes meaningful discriminative patterns rather than noise. Overall, the Grad-CAM++ analysis provides valuable interpretability by visualizing the relationship between learned representations and physical fault behaviors, thereby reinforcing the transparency and reliability of the proposed few-shot learning framework for fault diagnosis.

These findings confirm the proposed framework’s effectiveness in overcoming the core challenges of few-shot fault diagnosis in milling machine applications. Its perfect classification performance, interpretability through visualization tools, strong generalization under minimal data, and computational efficiency establish it as a strong candidate for real-world deployment. The framework is highly scalable and adaptable, and through its integration of adaptive prototype learning, Mahalanobis distance, and attention-driven feature extraction, consistently outperforms baseline few-shot learning approaches. It holds strong potential for extension to other industrial domains such as predictive maintenance, real-time monitoring, and anomaly detection. In summary, the proposed framework consistently demonstrated near-perfect performance under the 5-shot settings while maintaining strong generalization under more restrictive conditions. Its scalability, interpretability, and computational efficiency make it a practical and robust solution for real-world milling machine fault diagnosis.

Although the proposed framework demonstrates strong diagnostic performance and robustness across varying spindle speeds, certain limitations remain that present valuable opportunities for future improvement. The present study was conducted using AE data collected under controlled laboratory conditions, which may not fully capture the range of variability present in real industrial environments. Future work will therefore focus on extending the dataset to include multiple machines, tool materials, and cutting parameters to further validate domain generalization. In addition, while the current model performs effectively in offline analysis, deploying it in real-time monitoring systems will require optimization for computational efficiency and latency reduction. Moreover, since this study relied solely on AE signals, future extensions will explore the integration of multi-sensor information, such as vibration, cutting force, and spindle current, to improve robustness under noisy conditions. Finally, further evaluation under extremely low-shot or cross-domain conditions will be pursued to enhance model stability and adaptability. Addressing these aspects will help transition the proposed framework from laboratory validation to a fully scalable and explainable deployment in industrial TCM.