Assessment of Optical Light Microscopy for Classification of Real Coal Mine Dust Samples

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mine Dust Sampling

2.2. Selection of Samples for Analysis

2.3. Preparation of Dispersed Dust Samples

2.4. OLM Analysis

2.5. SEM-EDX Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

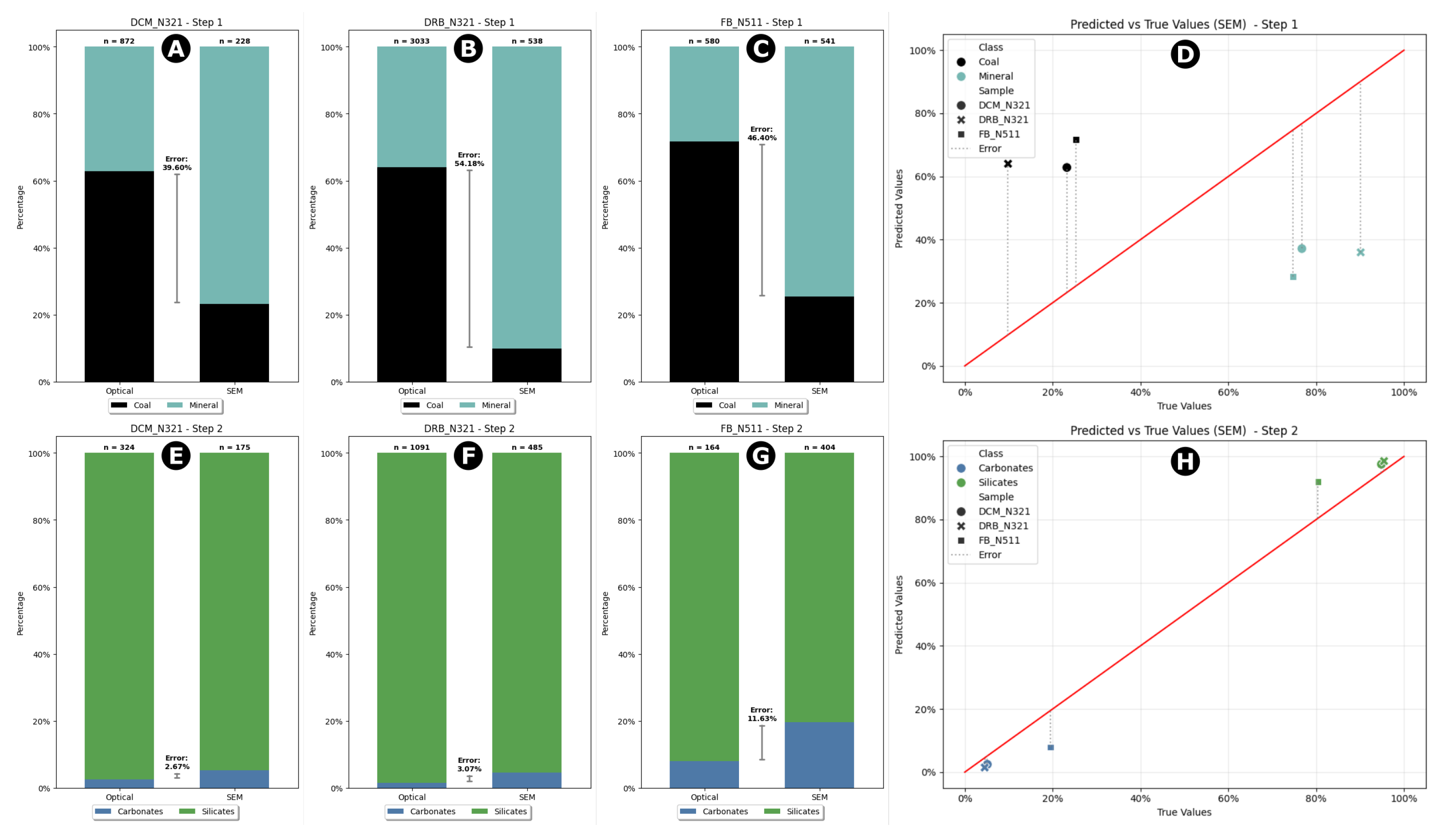

3.1. Direct-on-Substrate OLM

3.2. Dispersed Dust OLM

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

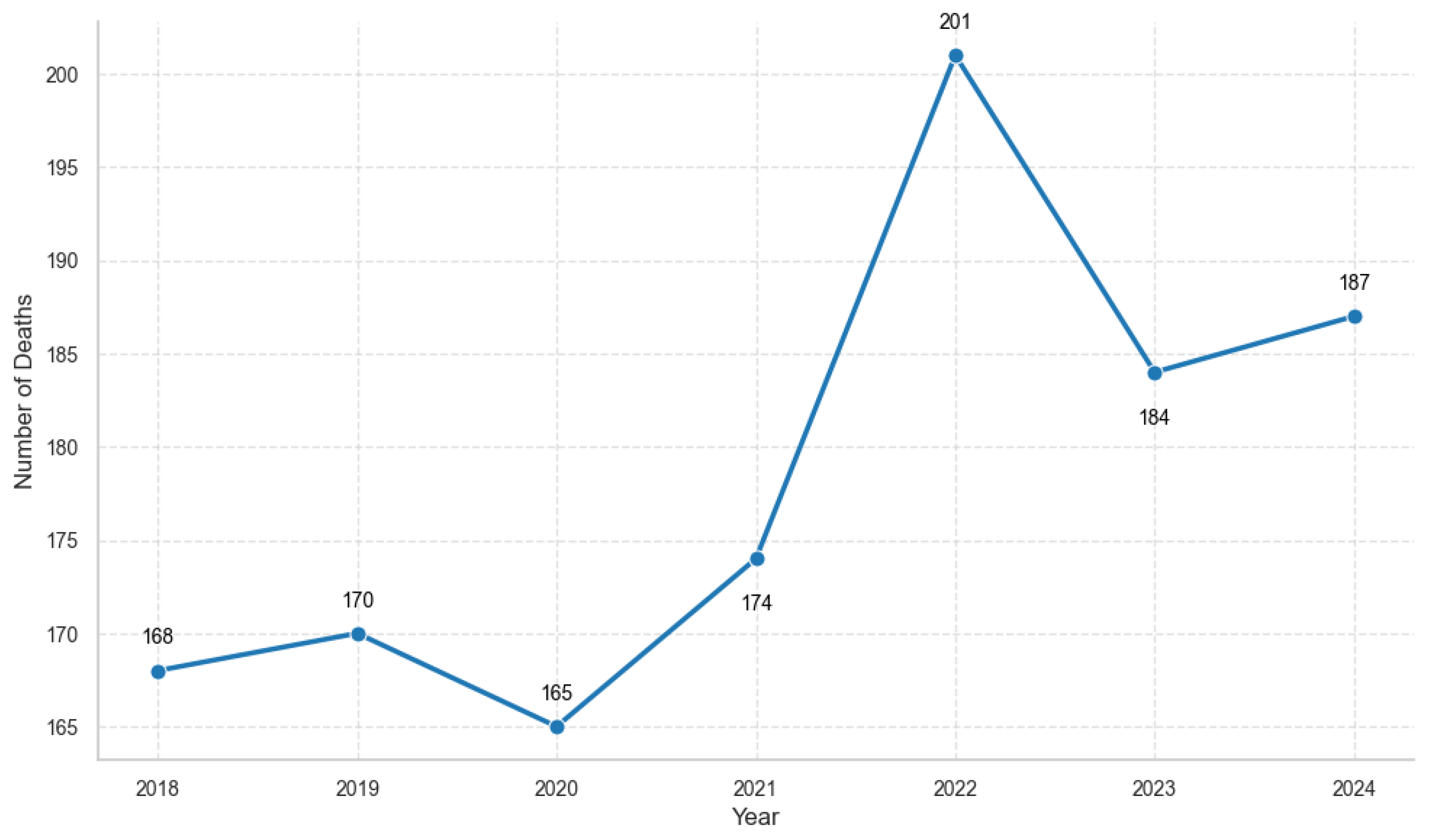

- Bell, J.L.; Mazurek, J.M. Trends in Pneumoconiosis Deaths — United States, 1999–2018. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. (MMWR) 2020, 69, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Optimizing Monitoring and Sampling Strategies. In Monitoring and Sampling Approaches to Assess Underground Coal Mine Dust Exposures; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Publishing House: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 78–97. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, B.; Wang, X.; Chow, J.C.; Watson, J.G.; Peik, B.; Nasiri, V.; Riemenschnitter, K.B.; Elahifard, M. Review of Respirable Coal Mine Dust Characterization for Mass Concentration, Size Distribution and Chemical Composition. Minerals 2021, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, N.A.; Xu, G.; Kumar, A.R.; Wang, Y. Calibration of low-cost particulate matter sensors for coal dust monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xue, N.; Wang, M. Evaluation and calibration of low-cost particulate matter sensors for respirable coal mine dust monitoring. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, A.; Walsh, P.T. Direct-Reading Inhalable Dust Monitoring—An Assessment of Current Measurement Methods. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2013, 57, 824–841. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.L.; Dobroski, H.; Cantrell, B.K. Technologies for Continuously Monitoring Respirable Coal Mine Dust. In Proceedings of the 12th WVU International Mining Electrotechnology Conference, Morgantown, WV, USA, 27–29 July 1994; pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zaid, M.M.; Amoah, N.; Kakoria, A.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G. Advancing occupational health in mining: Investigating low-cost sensors suitability for improved coal dust exposure monitoring. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 35, 025128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, N.; Keles, C.; Saylor, J.R.; Sarver, E. Demonstration of Optical Microscopy and Image Processing to Classify Respirable Coal Mine Dust Particles. Minerals 2021, 11, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, N.; Sarver, E. Advancing respirable coal mine dust source apportionment: A preliminary laboratory exploration of optical microscopy as a novel monitoring tool. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, N. Polarized Light Microscopy and Image Processing as a Near Real-time Monitoring Tool for Coal Mine Dust Monitoring. Doctoral Dissertation, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- National Vital Statistics System, Provisional Mortality on CDC WONDER Online Database. Available online: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-provisional.html (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Oldham, P.D. The Nature of the Variability of Dust Concentrations at the Coal Face. Occup. Environ. Med. 1953, 10, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, R.; Ramani, R.V. Experimental Studies on Dust Dispersion in Mine Airways; The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH): Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1989.

- Önder, M.; Önder, S.; Akdag, T.; Ozgun, F. Investigation of Dust Levels in Different Areas of Underground Coal Mines. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2009, 15, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, Z.; Feng, G. Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Respirable Dust After Blasting of Coal Roadway Driving Faces: A Case Study. Minerals 2015, 5, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daloğlu, G. CFD Modelling of the Dust and Air Velocity Behaviour at an Underground Coal Mine Roadway. Eskişehir Osman. Üniversitesi Mühendislik Ve Mimar. Fakültesi Derg. 2024, 32, 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, L. Agglomeration Of Coal Mine Dust and its Effect on Respirable Dust Sampling. In Inhaled Particles VI; Dodgson, J., McCallum, R.I., Bailey, M.R., Fisher, D.R., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sarver, E.; Sweeney, D.; Jaramillo Taborda, L.; Keles, C. Exploring agglomeration of respirable silica and other particles in coal mine dust. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Xiao, P.; Yan, D.; Li, S.; Hu, B.; Lin, H.; Liu, X. Experimental study of influence of coal dust physical–chemical properties on indirect dust suppression effect. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 302, 120799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Honaker, R. Optimized reagent dosage effect on rock dust to enhance rock dust dispersion and explosion mitigation in underground coal mines. Powder Technol. 2016, 301, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Shao, H.; Liang, Z.; Yang, T.; Chen, X. Research on the agglomeration and moisturizing mechanism of APAM composite surfactants on coal. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 420, 126780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Nie, B.; Ma, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C. A study of high-intensity high voltage electric pulse fracturing - A perspective on the energy distribution of shock waves. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 249, 213791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, E.; Keleş, Ç.; Ghaychi Afrouz, S. Particle size and mineralogy distributions in respirable dust samples from 25 US underground coal mines. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2021, 247, 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, L.; Agiotanti, E.; Afrouz, S.; Keles, C.; Sarver, E. Thermogravimetric analysis of respirable coal mine dust for simple source apportionment. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2022, 19, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann-Essex, V.; Keles, C.; Rezaee, M.; Scaggs-Witte, M.; Sarver, E. Respirable coal mine dust characteristics in samples collected in central and northern Appalachia. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2017, 182, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, E.; Keles, C.; Rezaee, M. Beyond conventional metrics: Comprehensive characterization of respirable coal mine dust. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 207, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, E.; Keles, C.; Rezaee, M. Characteristics of respirable dust in eight Appalachian coal mines: A dataset including particle size and mineralogy distributions, and metal and trace element mass concentrations. Data Brief 2019, 25, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.; Golden, S.; Assemi, S.; Sime, M.F.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Miller, J. Characterization of Particle Size and Composition of Respirable Coal Mine Dust. Minerals 2021, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Abbasi, B.; Elahifard, M.; Osho, B.; Chen, L.-W.A.; Chow, J.C.; Watson, J.G. Coal Mine Dust Size Distributions, Chemical Compositions, and Source Apportionment. Minerals 2024, 14, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluer, M.E.; Jaramillo Taborda, L.; Keles, C.; Sarver, E. Evaluation of advanced SEM-EDX tools for classification of complex particles in respirable dust. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 497, 139732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greth, A.; Afrouz, S.G.; Keles, C.; Sarver, E. Characterization of Respirable Coal Mine Dust Recovered from Fibrous Polyvinyl Chloride Filters by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yue, Z.; Yang, L.; Shen, A. Effects of Loading Rate and Notch Geometry on Dynamic Fracture Behavior of Rocks Containing Blunt V-Notched Defects. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 57, 2501–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analysis Type | Field Sample Name | OLM Frames | SEM-EDX Frames |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOS | DCM_N321 | 256 | 5 |

| DRB_N321 | 256 | 5 | |

| FB_N511 | 256 | 20 | |

| DD | DCM_N511 | 256 | 52 |

| DCM_N512 | 256 | 50 | |

| DRB_N51 | 50 | 213 | |

| DRB_N52 | 122 | 110 | |

| FB_N411 | 256 | 340 | |

| FB_N412 | 256 | 351 |

| Analysis Type | Field Sample Name | PAP 1 µm (%) | PAP 2.5 µm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOS | DCM_N321 | 38.78 | 51.91 |

| DRB_N321 | 36.68 | 62.16 | |

| FB_N511 | 42.37 | 72.29 | |

| DD | DCM_N511 | 30.05 | 52.41 |

| DCM_N512 | 35.97 | 51.41 | |

| DRB_N51 | 22.40 | 24.34 | |

| DRB_N52 | 32.90 | 45.29 | |

| FB_N411 | 27.27 | 46.19 | |

| FB_N412 | 25.65 | 42.33 |

| Sample | B | Silicates (%) | Carbonates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCM_N511 | 9.77 | 88.84 | 0.39 |

| DCM_N512 | 7.67 | 91.51 | 0.83 |

| DRB_N51 | 9.20 | 84.40 | 6.40 |

| DRB_N52 | 12.16 | 81.96 | 5.88 |

| FB_N411 | 35.97 | 56.95 | 7.08 |

| FB_N412 | 31.15 | 55.52 | 11.33 |

| Step | DCM_N511 | DRB_N51 | FB_N411 | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 µm | Step-1 | 17.49 | 2.14 | 4.78 | 10.54 |

| Step-2 | 12.14 | 2.03 | 6.33 | 7.99 | |

| 2.5 µm | Step-1 | 8.28 | 3.81 | 8.59 | 7.23 |

| Step-2 | 14.06 | 0.36 | 5.33 | 8.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Santa, N.; Jaramillo, L.; Sarver, E. Assessment of Optical Light Microscopy for Classification of Real Coal Mine Dust Samples. Minerals 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010015

Santa N, Jaramillo L, Sarver E. Assessment of Optical Light Microscopy for Classification of Real Coal Mine Dust Samples. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanta, Nestor, Lizeth Jaramillo, and Emily Sarver. 2026. "Assessment of Optical Light Microscopy for Classification of Real Coal Mine Dust Samples" Minerals 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010015

APA StyleSanta, N., Jaramillo, L., & Sarver, E. (2026). Assessment of Optical Light Microscopy for Classification of Real Coal Mine Dust Samples. Minerals, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010015