Geochronology and Geochemistry of Early–Middle Permian Intrusive Rocks in the Southern Greater Xing’an Range, China: Constraints on the Tectonic Evolution of the Paleo-Asian Ocean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Sampling and Analytical Methods

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Analytical Methods

4. Results

4.1. Whole-Rock Geochemistry

4.1.1. Major Oxides

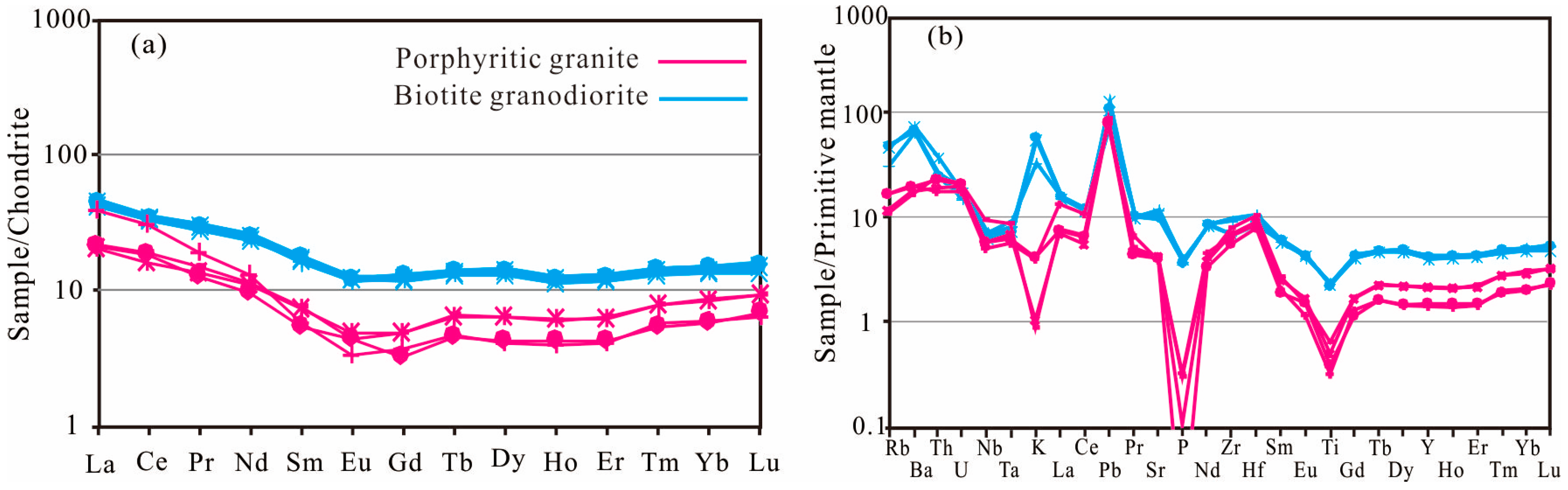

4.1.2. Trace Elements

| Sample | D1010-1 | D1010-2 | D1010-3 | D1010-4 | D1009-1 | D1009-2 | D1009-3 | D1009-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 64.43 | 64.63 | 64.96 | 64.28 | 77.05 | 77.30 | 77.88 | 76.61 |

| TiO2 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Al2O3 | 16.23 | 15.84 | 16.13 | 15.62 | 13.10 | 13.77 | 13.30 | 12.92 |

| FeO | 3.48 | 3.44 | 3.33 | 3.45 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.79 |

| Fe2O3 | 3.75 | 3.37 | 3.68 | 3.90 | 1.88 | 1.15 | 1.24 | 2.09 |

| MnO | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| MgO | 1.62 | 1.73 | 1.70 | 1.84 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| CaO | 4.33 | 4.59 | 4.16 | 4.62 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.90 |

| Na2O | 3.69 | 3.85 | 4.24 | 3.65 | 6.37 | 6.19 | 6.29 | 6.30 |

| K2O | 1.63 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1.80 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| P2O5 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| TFeO | 6.85 | 6.47 | 6.64 | 6.96 | 2.26 | 1.74 | 1.57 | 2.67 |

| LOI | 1.45 | 1.07 | 1.42 | 1.12 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| SUM | 99.87 | 99.90 | 99.89 | 99.89 | 99.84 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.98 |

| A/CNK | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.12 | 1.23 | 1.18 | 1.07 |

| A/NK | 2.07 | 1.92 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 1.25 | 1.33 | 1.27 | 1.24 |

| Mg# | 29.68 | 32.26 | 31.33 | 32.05 | 4.24 | 3.61 | 5.44 | 0.98 |

| Li | 12.8 | 8.6 | 14.8 | 9.5 | 7.4 | 9.7 | 8.8 | 7.6 |

| Sc | 18.80 | 18.98 | 19.43 | 19.93 | 9.42 | 8.01 | 7.01 | 9.65 |

| Co | 12.28 | 12.06 | 18.21 | 17.04 | 3.56 | 3.05 | 2.79 | 3.48 |

| Cs | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.27 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.78 |

| Hf | 2.62 | 2.77 | 3.29 | 3.24 | 2.81 | 2.50 | 2.65 | 3.25 |

| Ta | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.36 |

| Th | 3.09 | 2.09 | 2.04 | 2.21 | 1.64 | 1.97 | 1.51 | 2.08 |

| U | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.45 |

| B | 2.03 | 1.09 | 1.70 | 1.46 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.02 |

| Ba | 504 | 476 | 452 | 461 | 124 | 138 | 143 | 114 |

| Cr | 31.0 | 36.5 | 35.8 | 37.7 | 44.8 | 19.4 | 33.5 | 26.2 |

| Cu | 10.49 | 10.88 | 10.81 | 12.61 | 4.05 | 4.21 | 3.39 | 4.27 |

| Ga | 30.3 | 24.4 | 24.0 | 14.1 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.0 | 16.0 |

| Nb | 4.48 | 4.90 | 5.14 | 4.98 | 4.20 | 4.17 | 3.67 | 6.84 |

| Ni | 7.8 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Pb | 8.98 | 7.77 | 6.82 | 5.27 | 6.00 | 5.76 | 5.45 | 6.29 |

| Rb | 29.6 | 30.3 | 19.8 | 31.6 | 7.5 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 6.9 |

| Sr | 231 | 211 | 246 | 204 | 90 | 87 | 84 | 90 |

| V | 135 | 133 | 141 | 145 | 38 | 25 | 23 | 39 |

| Zn | 56.0 | 55.3 | 60.1 | 87.0 | 22.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 | 20.2 |

| Zr | 76 | 76 | 103 | 109 | 78 | 64 | 75 | 90 |

| Y | 18.3 | 19.3 | 18.6 | 19.5 | 10.0 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 9.9 |

| La | 10.2 | 10.9 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 9.3 | 5.4 |

| Ce | 20.5 | 21.2 | 20.6 | 20.8 | 10.0 | 11.6 | 19.4 | 12.1 |

| Pr | 2.70 | 2.85 | 2.77 | 2.80 | 1.34 | 1.24 | 1.87 | 1.44 |

| Nd | 11.3 | 11.7 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 5.5 |

| Sm | 2.60 | 2.70 | 2.64 | 2.53 | 1.14 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 1.20 |

| Eu | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| Gd | 2.45 | 2.58 | 2.62 | 2.58 | 1.02 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 1.03 |

| Tb | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.25 |

| Dy | 3.42 | 3.60 | 3.48 | 3.56 | 1.66 | 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.66 |

| Ho | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.35 |

| Er | 2.00 | 2.09 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 1.06 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 1.10 |

| Tm | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| Yb | 2.34 | 2.45 | 2.53 | 2.50 | 1.45 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.53 |

| Lu | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.24 |

| ΣREE | 60 | 63 | 61 | 62 | 29 | 28 | 42 | 32 |

| LREE | 48 | 50 | 49 | 49 | 23 | 24 | 38 | 26 |

| HREE | 12.1 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 6.4 |

| LaN/YbN | 3.11 | 3.19 | 2.97 | 3.09 | 2.42 | 3.71 | 6.46 | 2.52 |

| δEu | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| δCe | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 1.09 | 1.07 | 1.04 |

4.2. Zircon U–Pb Ages

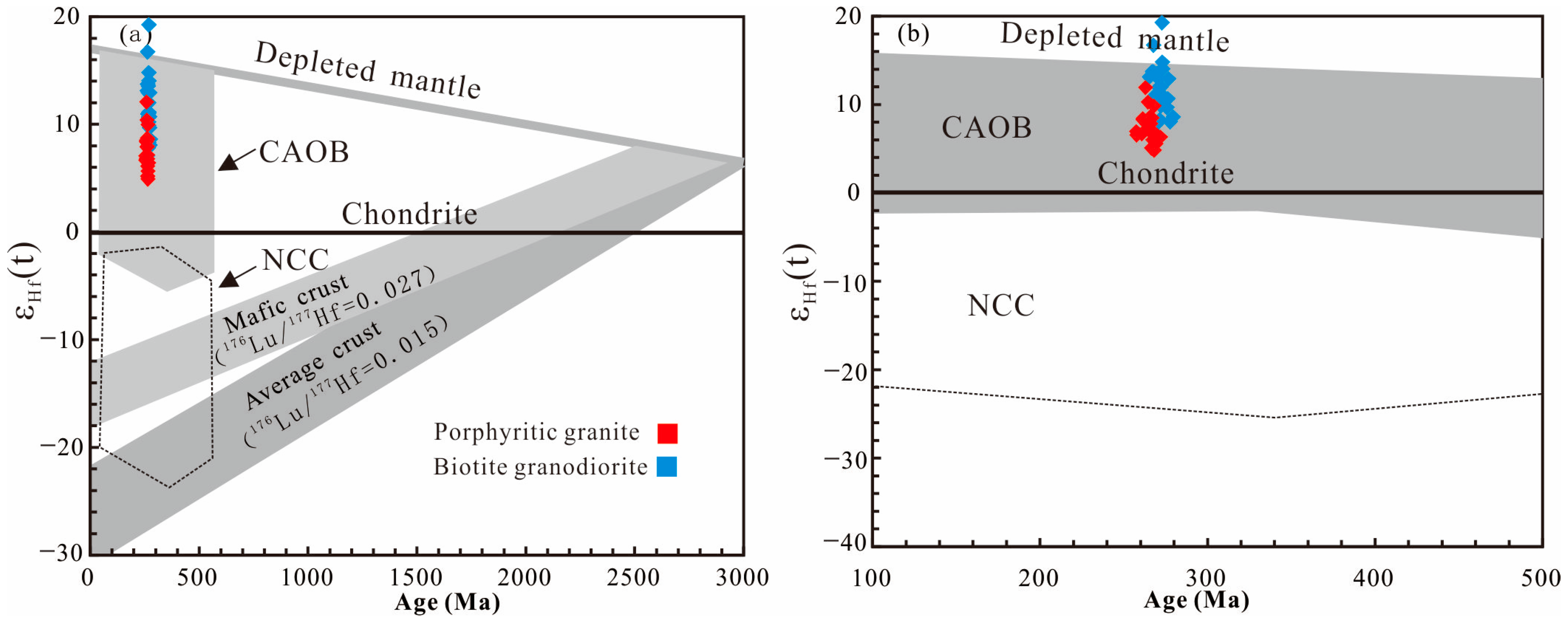

4.3. Lu-Hf Isotopic Characteristics

5. Discussion

5.1. Age of Early–Middle Permian Magmatism

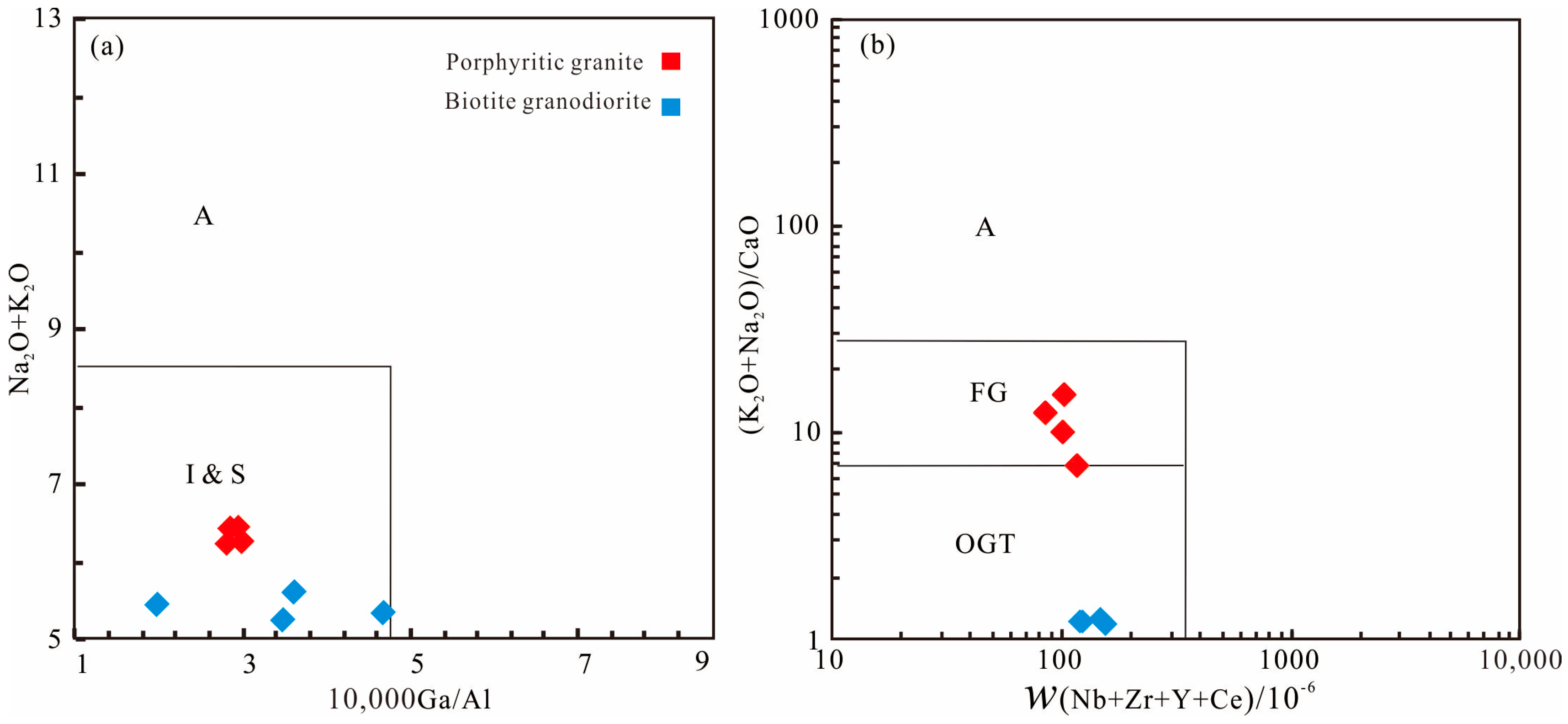

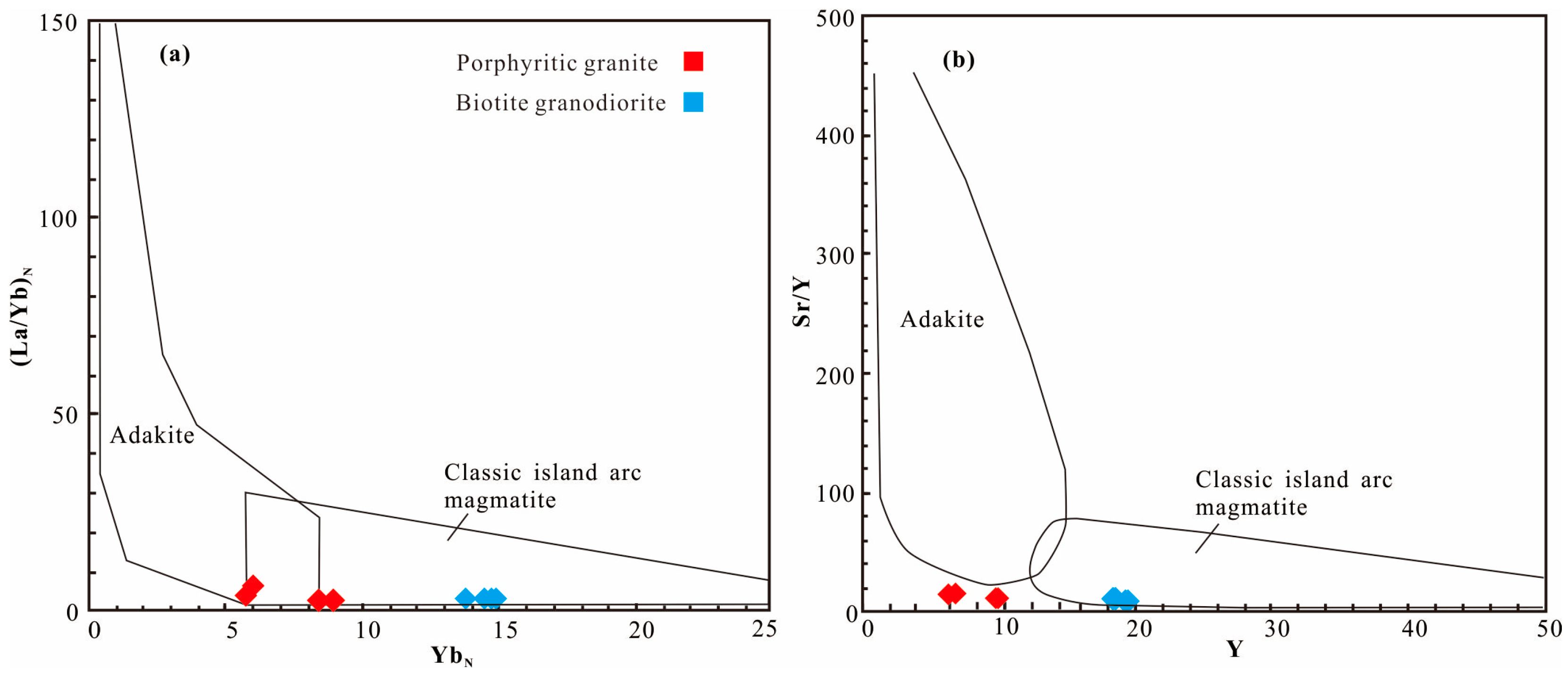

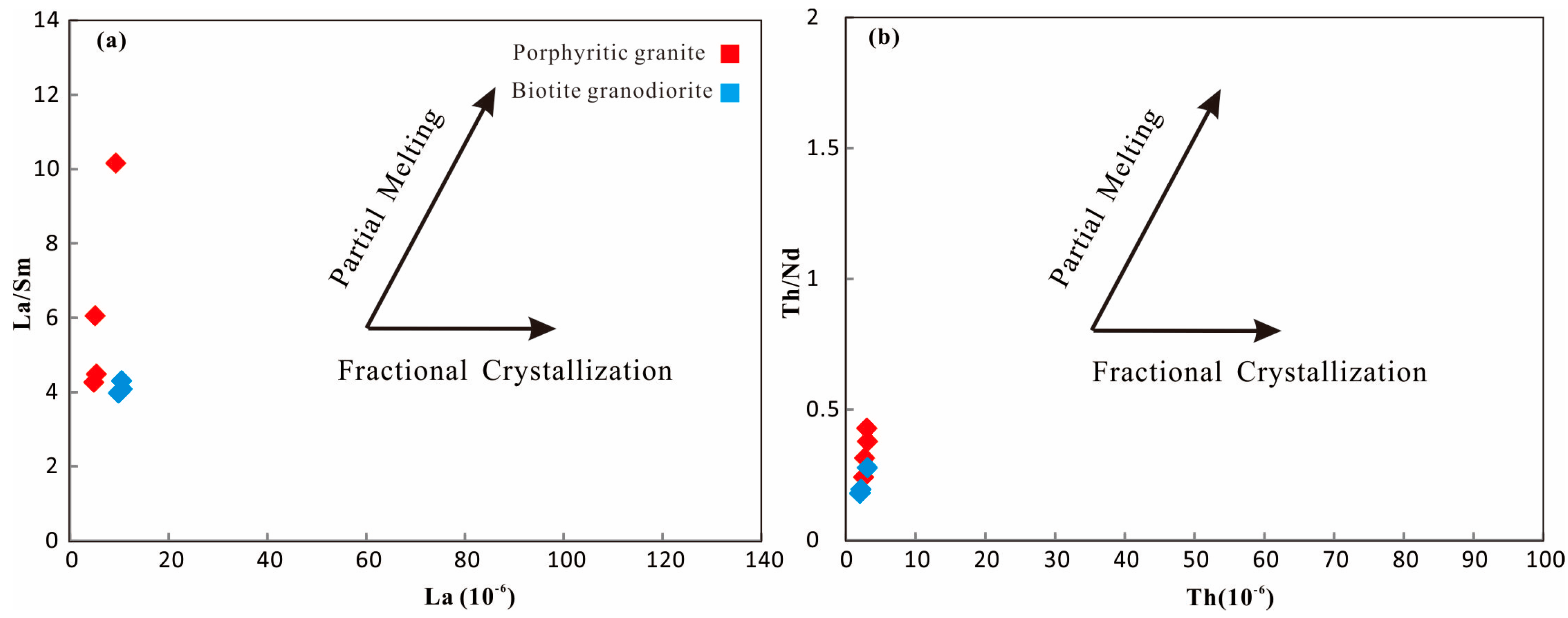

5.2. Magmatic Origin and Nature of the Source Region

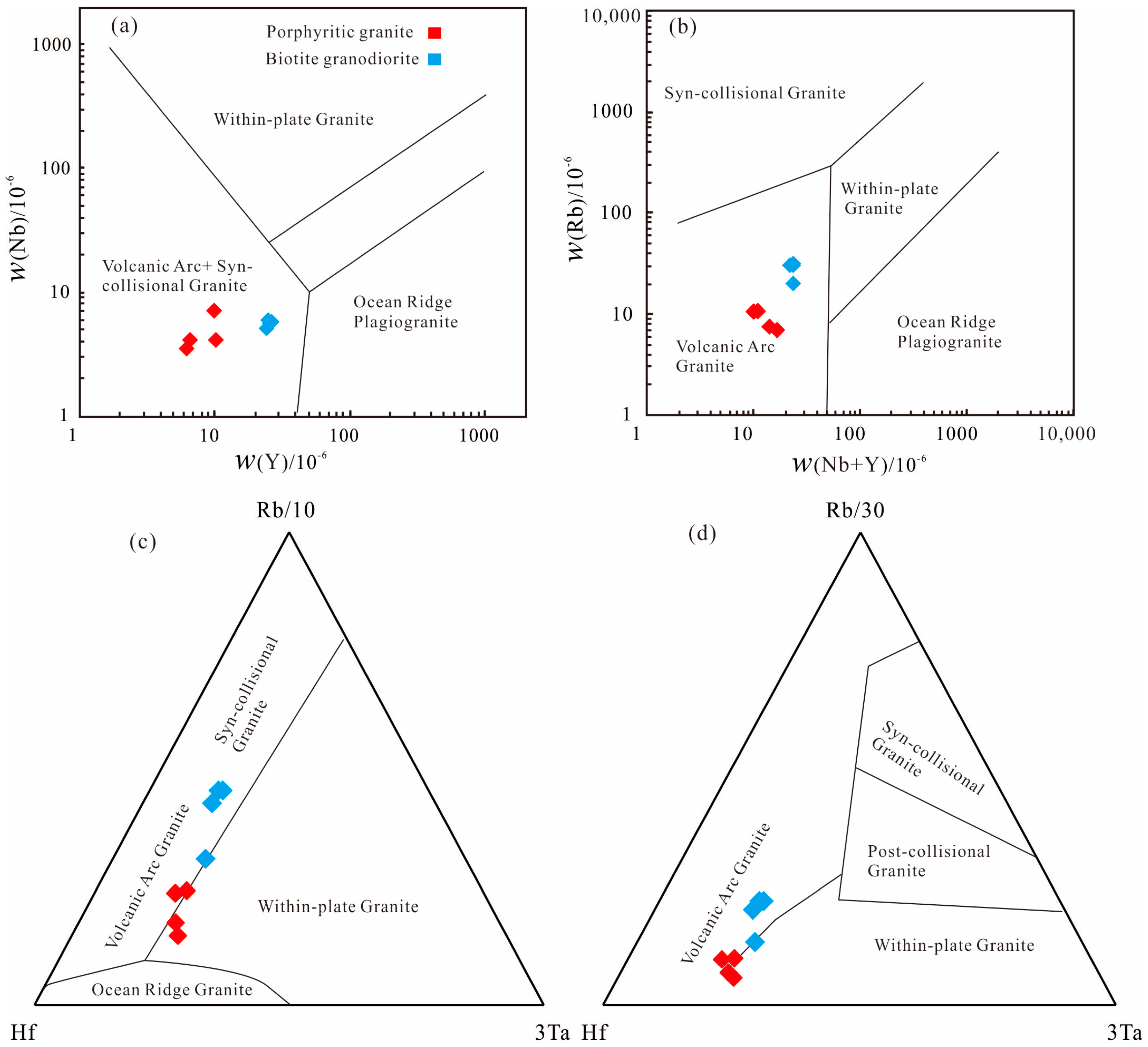

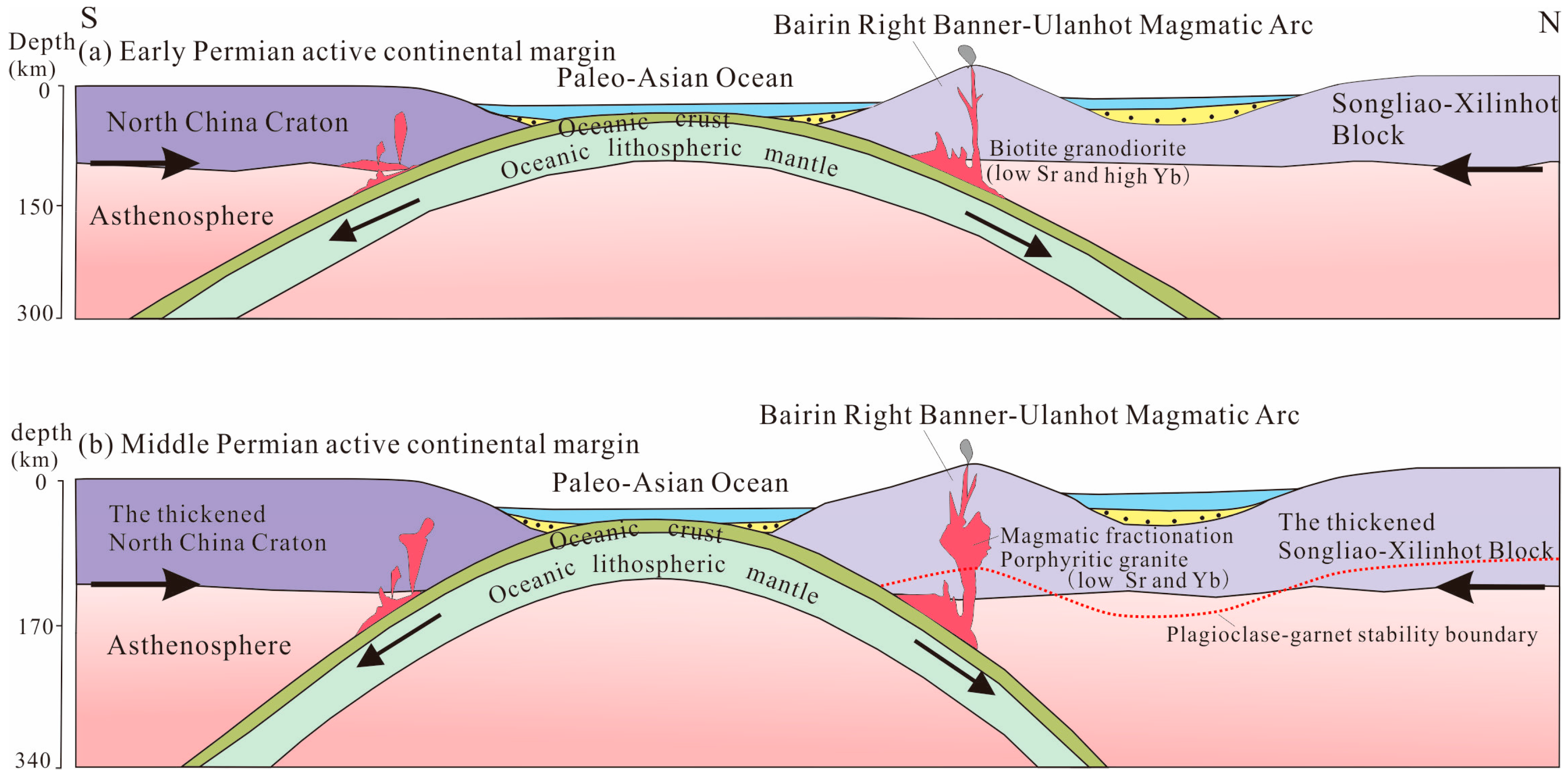

5.3. Tectonic Setting of Magmatic Rocks and Its Constraints on the Evolution of the PAO

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Zircon U–Pb dating yielded ages of 273.2 ± 1.4 Ma and 264.4 ± 1.5 Ma for the newly identified Late Paleozoic intrusions, representing the emplacement and crystallization ages. These results indicate that the biotite granodiorite and porphyritic granite formed during the Early and Middle Permian, respectively.

- (2)

- The Early to Middle Permian intrusions are geochemically characterized by high SiO2 content, low CaO and MgO content, and a metaluminous to weakly peraluminous composition, features typical of I-type granites. The Early Permian intrusion formed under plagioclase-stable conditions, displaying a low–Sr and high–Yb signature. In contrast, the Middle Permian intrusion was derived from partial melting at greater depths and experienced fractional crystallization during ascent, resulting in a low-Sr and low-Yb granite. Positive zircon εHf(t) values and young Hf model ages indicate that both intrusions were sourced from juvenile crustal melts, likely triggered by mantle-derived magmatism in a subduction-related setting.

- (3)

- During the Early to Middle Permian, the Paleo-Asian Ocean plate continued to subduct beneath the Songliao–Xilinhot Block in the central-southern Great Xing’an Range. This subduction intensified during the Middle Permian, leading to significant crustal thickening, and the region remained in an active continental margin setting, with was no collision involving the Paleo-Asian Ocean.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Natal’in, B.A.; Burtman, U.S. Evolution of the Altaid tectonic collage and Paleozoic crustal growth in Eurasia. Nature 1993, 364, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, S.A.; Zhang, X.Z.; Wu, F.Y. Extension of a newly identified 500Ma metamorphic terrane in North East China: Further U–Pb SHRIMP dating of the Mashan Complex, Heilongjiang Province, China. Tectonophysics 2000, 328, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Windley, B.F.; Hao, J.; Zhai, M. Accretion leading to collision and the Permian Solonker suture, Inner Mongolia, China: Termination of the central Asian orogenic belt. Tectonics 2003, 22, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Windley, B.F.; Sun, S.; Li, J.; Huang, B.; Han, C.; Yuan, C.; Sun, M.; Chen, H. A tale of amalgamation of three Permo-Triassic collage systems in Central Asia: Oroclines, sutures, and terminal accretion. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 43, 477–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.M. The Central Asian Orogenic Belt and growth of the continental crust in the Phanerozoic. In Aspects of the Tectonic Evolution of China; Malpas, J., Fletcher, C.J.N., Ali, J.R., Aitchison, J.C., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2004; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Windley, B.F.; Alexeiev, D.; Xiao, W.; Kröner, A.; Badarch, G. Tectonic models for accretion of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2007, 164, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y. Somenewideason tectonics of NE China and its neighboring areas. Geol. Rev. 1998, 44, 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.H.; Chen, Y.S.; Wang, S.J.; Li, C.H. Late Mesozoic magmatism and tectonic significance of the Kelihe area in the northern Great Xingan Range. Geol. J. 2022, 57, 1311–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Feng, Z.Q.; Jiang, L.W.; Jin, W.; Li, W.M.; Guan, Q.B.; Wen, Q.B.; Liang, C.Y. Ophiolite in the eastern Central Asian orogenic belt, NE China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2019, 35, 3017–3047. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Zhao, P.; Bao, Q.Z.; Zhou, Y.H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Luo, Z.W. Preliminary study on the pre Mesozoic tectonic unit division of the Xing Meng Orogenic Belt (XMOB). Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 1841–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Hai, L.F.; Zhao, D.S. Zircon U–Pb ages, Hf isotope and extensional tectonics of monzogranite in the Hansumu area of southern Great Khingan. Geol. China. 2021, 48, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.Y.; Zhao, G.C.; Sun, D.Y.; Wilde, S.A.; Yang, J.H. The Hulan Group: Its role in the evolution of the Central Asian omgenic belt of NE China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2007, 30, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Sun, D.Y.; Ge, W.C.; Zhang, Y.B.; Grant, M.L.; Wilde, S.A.; Jahn, B.M. Geochronology of the Phanerozoic granitoidsin northeastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, W.M.; Ma, Y.F.; Feng, Z.Q.; Guan, Q.B.; Li, S.Z.; Chen, Z.X.; Liang, C.Y.; Wen, Q.B. An orocline in the eastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 221, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, W.M.; Feng, Z.Q.; Wen, Q.B.; Neubauer, F.; Liang, C.Y. A Review of the Paleozoic Tectonics in the Eastern Part of Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 2017, 43, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.B.; Li, S.C.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Li, P.C. Zircon U–Pb dating, geochemistry and geological significance of the I–type granites in Helong area, the eastern section of the southern margin of Xing–Meng Orogenic Belt. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 32, 2690–2706. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.X. Characteristics of Early Permian –Middle Triassic Volcanic Rocks in Faku–Kaiyuan, Eastern Part of the Northern Margin of the North China Block and Their Tectonic Significance. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2021; pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.H.; Xu, W.L.; Pei, F.P.; Wang, Z.W.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.J. Zircon U–Pb geochronology and petrogenesis of the ate Pal eozoic– Eady Mesozoic intrusive rocks in the eastern segment of the northern margin of the North China block. Lithos 2013, 170, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, S.S.; Chen, X.; Huan, F.M. The extinction process of the paleo–oceanic basin in the eastem part of the northern margin of the North China Block: Implications from the intermediate–malic magmatic rocks in the northern Liaoning, NE China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2022, 38, 2292–2322. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.L.; Wang, F.; Pei, F.P.; Meng, E.; Tang, J.; Xu, M.J.; Wang, W. Mesozoic Tectonic Regimes and Regional Ore–Forming Background in NE China: Constraints from Spatial and Temporal Variations of Mesozoic Volcanic Rock Associations. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2013, 29, 339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Chen, Y.; Xu, B.; Faure, M.; Shi, G.Z.; Choulet, F. Did the Paleo–Asian Ocean between North China Block and Mongolia block exist during the Late Paleozoic? First paleomagnetic evidence from central–eastem Inner Mongolia, China. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 1873–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Li, K.; Li, J.F.; Tang, W.H.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Z.W. Geoc hronology and geochemistry of the eastern Erenhot ophiolitic complex: Implications for the tectonic evolution of the Inner Mongolia–Daxinganling orogenicbelt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 97, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.R.; Chu, H.; Wei, C.J.; Wang, K. Geochemical characteristics and tectonic significance of Late Paleoaoic–Early Mesozoic meta–basic rocks in the mélange zones, central: Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 1935–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.G.; Wang, M.M.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Niu, Y.L.; Allen, M.B.; Su, L. Ophiolites in the Xing ‘an–Inner Mongolia accretionary belt of the CAOB: Implications for two cycles of seafloor spre adingand accretionary orogenic events. Tectonics 2015, 34, 2221–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Zhao, Y.; Song, B.; Yang, Z.Y.; Hu, J.M.; Wu, H. Carboniferous granitic plutons from the northern margin of the North China block: Implications for a late Palaeozoic active continental margin. J. Geol. Soc. 2007, 164, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H.; Wilde, S.M.; Zhang, H.F.; Tang, Y.J.; Zhai, M.G. Geochemistry of hornblende gabbros from Sonidzuoqi, Inner Mongolia, North China: Implications for magmatism during the final stage of suprasubductionzone ophiolite formation. Int. Geol. Rev. 2009, 51, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Z.C.; Feng, Z.S.; Li, J.F.; Tang, W.H.; Luo, Z.W. Zircon SHRIMP U–Pb dating and its geological significance of the Late–Carboniferous to Early–Permian volcanic rocks in Bayanwula area, the central of Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 2041–2054. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Jahn, B.M.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y.B.; Xiao, W.J. Geochemistry, geochronology and zircon Hf isotopic study of peralkaline–alkaline intrusions along the northern margin of the North China Craton and its tectonic implication for the southeastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Lithos 2016, 261, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xu, B.; Zhang, C.H. A rift system in southeastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Constraint from sedimentological, geochronological and geochemical investigations of the Late Carboniferous–Early Permian strata in northern Inner Mongolia (China). Gondwana Res. 2017, 47, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubchuk, A. Architecture and mineral deposit settings of the Altaid orogenic collage: A revised model. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2004, 23, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Gao, L.M.; Sun, G.H.; Li, Y.P.; Wang, Y.B. Shuangjingzi Middle Triassic syn-collisional crust derived granite in the East Inner Mongolia and its constraint on the timing of collision between Siberian and Sino Korean paleo-plates. Acta Petrol Sin. 2007, 23, 565–582. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, T.N.; Li, Y.P.; Sun, G.H.; Zhu, Z.X.; Wang, L.J. Crustal Tectonic Division and Evolution of the Southern Part of the North Asian Orogenic Region and Its Adjacent Areas. J. Jilin Univ. Earth Sci. Ed. 2009, 39, 584–605. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.F.; Li, J.Y.; Sun, L.X.; Yin, D.F.; Zheng, P.X. Zircon U–Pb dating of the Jiujingzi ophiolite in Bairin Left Banner, Inner Mongolia: Constraints on the formation and evolution of the Xar Moron River suture zone. Geol. China 2016, 43, 1947–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.M.; Hu, J.M.; Song, B.; Liu, J.; Wu, H. Geochronology‚geochemistry and tectonic setting of the Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic magmatism in the northern margin of the North China Block: A preliminary review. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2010, 29, 824–842. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, P.; Liu, D.Y.; Kröner, A.; Windley, B.F.; Shi, Y.R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.Q.; Miao, L.C. Time scale of an early to mid–Paleozoic orogenic cycle of the long–lived Central Asian Orogenic Belt, Inner Mongolia of China: Implications for continental growth. Lithos 2008, 101, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, P.; Liu, D.Y.; Kröner, A.; Windley, B.F.; Shi, Y.R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.Q.; Miao, L.C.; Zhang, L.Q.; Tomurhuu, D. Evolution of a Permian intraoceanic arc–trench system in the Solonker suture zone, Central Asian Orogenic Belt, China and Mongolia. Lithos 2010, 118, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Zhao, Y.; Kröner, A.; Liu, X.M.; Xie, L.W.; Chen, F.K. Early Permian plutons from the northern North China Block: Constraints on continental arc evolution and convergent margin magmatism related to the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2009, 98, 1441–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.D.; Fang, J.Q.; Zhao, P.; Xu, B.; Bao, Q.Z.; Zhou, Y.H.; Deng, R.J. Detrital zircon ages of the Silurian–Devonian clastic rocks in south and north banks of Xar Moron River, Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.D. Tectonic development of Paleozoic foldbelts at the north margin of the Sino–Korean craton. Tectonics 1990, 9, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.A. The Crustal Evolution in Northern Margin Middle Segment of the Sino–Korean Plate; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 1991; pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.A.; Wang, Y.; Tang, K.D. A reflection on the Xarmoron tectonomagmatic belt, Inner Mongolia, China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 3002–3010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Yang, Z.N.; He, Y. The Xing–Meng Intracontinent Orogenic Belt. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2018, 34, 2819–2844. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H.; Zhang, G.B.; Xu, B. The Late Paleozoic extending and thinning processes of the Xing’an–Mongolia orogenic belt: Geochemical evidence from the plutons in Linxi area, Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2021, 37, 2029–2050. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.J.; Windley, B.F.; Huang, B.C.; Han, C.M.; Yuan, C.; Chen, H.L.; Sun, M.; Sun, S.; Li, J.L. End–Pemian to Mid–Triassic termination of the accretionary processes of the southern Altaids: Implications for the geodynamic evolution, Phanerozoic continental growth, and metallogeny of Central Asia. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2009, 98, 1189–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F.; Li, J.Y.; Chi, X.G.; Qu, J.F.; Hu, Z.C.; Fang, S.; Zhang, Z. ALate–CarboniferoustoearlyEarly–Pemian subduction–. accretion complex in Daqing pasture, southeastern Inner M ongolia: Evidence of northward subduction beneath the Siberian paleoplate southernmargin. Lithos 2013, 177, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Charvet, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, P.; Shi, G.Z. Middle Paleozoic convergent orogenic belts in western Inner Mongolia (China): Framework, kinematics, geochronology and implications for tectonic evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 2013, 23, 1342–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Liu, J.F.; Qu, J.F.; Zheng, R.G.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.X.; Li, Y.F.; Yang, X.P.; Wang, L.J.; et al. Major geological features and crustal tectonic framework of Northeast China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2019, 35, 2989–3016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.F.; Li, J.Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, R.G.; Zhang, W.L.; Lu, Q.L.; Zheng, P.X. Crustal accretion and Paleo–Asian Ocean evolution during Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic in southeastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Evidence from magmatism in Linxi–Dongwuqi area, southeastern Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2022, 38, 2181–2215. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Jahn, B.M.; Tian, W. Evolution of the Solonker ssuture zone: Constraints fromzircon U–Pb ages, Hf isotopic ratios and whole–rock Nd–Sr isotope compositions of subduction–and collision–related magmas and forearc sediments. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2009, 34, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.P. TEMORA 1: A new zircon standard for Phanerozoic U-Pb geochronology. Chem. Geol. 2003, 200, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Tang, G.Q.; Guo, B.; Yang, Y.H.; Hou, K.J.; Hu, Z.C.; Li, Q.L.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.X. Qinghu zircon: A working reference for microbeam analysis of U–Pb age and Hf and O isotopes. China Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T. Correction of common lead in U-Pb analyses that do not report 204Pb. Chem. Geol. 2002, 192, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Xie, L.W.; Yang, J.H.; Xu, P. Hf isotopic compositions of the standard zircons and baddeleyites used in U–Pb geochronology. Chem. Geol. 2006, 234, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Hu, J.; Greggoire, C. Determination of trace elements in granites by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Talanta 2000, 51, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochum, K.P.; Nohl, U.; Herwig, K.; Lammel, E.; Stoll, B.; Hofmann, A.W. GeoReM: A new geochemical database for reference materials and isotopic standards. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2005, 29, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, P.J.; Kane, J.S. International association of geoanalysts certificate of analysis: Certified reference material Ou-6 (Penrhyn Slate). Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2005, 29, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, R.W.L. A Classiffcation of Igneous Rocks and Glossary of Terms; Blackwell Scientiffc: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Peccerillo, A.; Taylor, S.R. Geochemistry of Eocene Calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the Kastamonu area, northern Turkey. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1976, 58, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. In Magmatism in the Ocean Basins; Saunders, A.D., Norry, M.J., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 1989; Volume 42, pp. 313–345. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.F.; Sun, S.S. The composition of the earth. Chem. Geol. 1995, 120, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boynton, W.V. Cosmochemistry of the rare earth elements: Meteorite studies. In Rare Earth Element Geochemistry; Henderson, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 63–114. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.S.; Xiao, E.; Hu, J.; Xu, X.S.; Jiang, S.Y.; Li, Z. Petrogenesis of highly fractionated I–type granites in the coastal area of northeastern Fujian Province: Constraints from zircon U–Pb geochronology, geochemistry and Nd–Hf isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2008, 24, 2468–2484. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, B.W.; Bryant, C.J.; Wyborn, D. Peraluminous I–type granites. Lithos 2012, 153, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Liu, D.; Zhao, Z.D.; Yan, J.J.; Shi, Q.S.; Mo, X.X. The Sangri highly fractionated I–type granites in southern Gangdese: Petrogenesis and dynamic implication. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 2479–2493. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, R.J. Subduction zones. Rev. Geophys. 2002, 40, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Late Ordovician–Late Triassic Tectonic Evolution of Faku Area in the Eastern Segment of the Northern Margin of the North China Craton–Evidence from Magmatic Activity. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Whalen, J.B.; Currie, K.L.; Chappell, B.W. A–type granites: Geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 95, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, M.J.; Drummond, M.S. Derivation of some modern arc magmas by melting of young subducted lithosphere. Nature 1987, 347, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Ge, W.C.; Yang, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Ji, Z. The Early Paleozoic granites in the Mohe region of northern Great Xing’an Range: Response to post–collision extension of the Erguna–Xing’an blocks. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2022, 38, 2397–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.Y. Tectonic Evolution of Xar–Moron Suture Zone in Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic: Evidence of Tectono–Magmatic Activity from Balinyou–Ar Horqin Banner. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.L.; Cheng, Z.G. Mineralogical and Hf isotope study of the Dorol granite in Hinggan League, Inner Mongolia. Geol. China 2016, 43, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, R.P.; Shimizu, N.; Norman, M.D.; Applegate, G.S. Reaction between slab–derived melts and peridotite in the mantle wedge: Experimental constraints at 3.8 GPa. Chem. Geol. 1999, 160, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.D.; Wang, Y.L.; Jin, W.J.; Jia, X.Q. Granite classification on the basis of Srand Yb contents and its implications. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2006, 22, 2249–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A.; Harris, N.B.W.; Tindle, A.G. Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks. J. Petrol. 1984, 25, 956–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, N.J.G.; Perkins, W.T.; Westgate, J.A.; Gorton, M.P.; Jackson, S.E.; Neal, C.R.; Chenery, S.P. A compilation of new and published major and trace element data for NIST SRM 610 and NIST SRM 612 glass reference materials. Geostand. Newsl. 1997, 21, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Zhao, Y.; Song, B.; Wu, H. The late Paleozoic gneissic granodiorite pluton in early Precambrian high–grade metamorphic terrains near Longhua County in northern Hebei Province‚North China: Result from zircon SHRIMP U–Pb dating and its tectonic implications. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2004, 20, 621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.C.; Zhao, F.Q.; Li, H.M.; Sun, L.X.; Miao, L.C.; Ji, S.P. Zircon SHRIMP U–Pb age of the dioritic rocks from northern Hebei: The geological records of late Paleozoic magmatic arc. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.S. Petrogenesis of the Late Paleozoic to Early Mesozoic Granites from the Chifeng Region and Their Tectonic Implication. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.N.; Zhang, Y.F.; Peng, R.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Q.D. Whole–rock Geochemistry, Zircon U–Pb Ages, and Hf Isotopic Characteristics of Ore–related Intrusions of the Tin Polymetallic Deposits in the Southern Great Xing’an Range and Their Geological Significance: Case Studies of the Bianjiadayuan, Maodeng, and Baogaigou Deposit. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2024, 46, 343–360. [Google Scholar]

| Sample No. | Content (ppm) | Th/U | Isotope Ratio | Age/Ma | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th | U | 207Pb/206Pb | ±1σ | 207Pb/235U | ±1σ | 206Pb/238U | ±1σ | rho | 206Pb/238U | ±1σ | Concordance | ||

| D1010–1 | 506 | 539 | 0.94 | 0.0521 | 0.0018 | 0.307 | 0.011 | 0.0426 | 0.0005 | 0.32 | 269 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1010–2 | 150 | 200 | 0.75 | 0.0525 | 0.0020 | 0.311 | 0.012 | 0.0432 | 0.0005 | 0.30 | 273 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1010–3 | 235 | 272 | 0.87 | 0.0530 | 0.0021 | 0.322 | 0.013 | 0.0441 | 0.0005 | 0.26 | 278 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1010–4 | 393 | 399 | 0.98 | 0.0526 | 0.0027 | 0.324 | 0.018 | 0.0446 | 0.0008 | 0.32 | 281 | 5 | 0.98 |

| D1010–5 | 92 | 161 | 0.57 | 0.0501 | 0.0042 | 0.302 | 0.028 | 0.0432 | 0.0010 | 0.26 | 273 | 6 | 0.98 |

| D1010–6 | 148 | 181 | 0.82 | 0.0512 | 0.0049 | 0.302 | 0.033 | 0.0422 | 0.0011 | 0.25 | 267 | 7 | 0.99 |

| D1010–7 | 146 | 173 | 0.85 | 0.0543 | 0.0095 | 0.319 | 0.049 | 0.0441 | 0.0022 | 0.32 | 278 | 13 | 0.98 |

| D1010–8 | 214 | 270 | 0.79 | 0.0524 | 0.0018 | 0.310 | 0.010 | 0.0429 | 0.0004 | 0.31 | 271 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1010–9 | 514 | 596 | 0.86 | 0.0525 | 0.0113 | 0.307 | 0.052 | 0.0426 | 0.0020 | 0.28 | 269 | 13 | 0.99 |

| D1010–10 | 280 | 312 | 0.90 | 0.0507 | 0.0044 | 0.301 | 0.029 | 0.0427 | 0.0011 | 0.26 | 270 | 7 | 0.99 |

| D1010–11 | 358 | 314 | 1.14 | 0.0520 | 0.0038 | 0.308 | 0.020 | 0.0435 | 0.0007 | 0.23 | 275 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1010–12 | 191 | 229 | 0.83 | 0.0530 | 0.0020 | 0.312 | 0.011 | 0.0430 | 0.0005 | 0.32 | 271 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1010–13 | 105 | 187 | 0.56 | 0.0514 | 0.0020 | 0.301 | 0.012 | 0.0426 | 0.0005 | 0.29 | 269 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1010–14 | 124 | 183 | 0.68 | 0.0519 | 0.0022 | 0.317 | 0.014 | 0.0440 | 0.0006 | 0.29 | 277 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1010–15 | 666 | 549 | 1.21 | 0.0503 | 0.0014 | 0.303 | 0.009 | 0.0434 | 0.0005 | 0.37 | 274 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1010–16 | 130 | 186 | 0.70 | 0.0520 | 0.0034 | 0.309 | 0.019 | 0.0433 | 0.0006 | 0.21 | 273 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1010–17 | 114 | 181 | 0.63 | 0.0514 | 0.0024 | 0.314 | 0.015 | 0.0443 | 0.0006 | 0.27 | 279 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1010–18 | 451 | 430 | 1.05 | 0.0523 | 0.0021 | 0.312 | 0.012 | 0.0431 | 0.0005 | 0.29 | 272 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1010–19 | 287 | 312 | 0.92 | 0.0505 | 0.0017 | 0.301 | 0.010 | 0.0431 | 0.0005 | 0.35 | 272 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1010–20 | 168 | 215 | 0.78 | 0.0520 | 0.0023 | 0.313 | 0.014 | 0.0434 | 0.0006 | 0.30 | 274 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1010–21 | 147 | 192 | 0.76 | 0.0518 | 0.0028 | 0.301 | 0.015 | 0.0425 | 0.0006 | 0.28 | 268 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1010–22 | 558 | 496 | 1.12 | 0.0505 | 0.0014 | 0.305 | 0.009 | 0.0435 | 0.0005 | 0.39 | 274 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1010–23 | 218 | 248 | 0.88 | 0.0512 | 0.0019 | 0.307 | 0.012 | 0.0434 | 0.0005 | 0.30 | 274 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1010–24 | 274 | 305 | 0.90 | 0.0516 | 0.0016 | 0.310 | 0.010 | 0.0434 | 0.0005 | 0.33 | 274 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1010–25 | 524 | 488 | 1.07 | 0.0523 | 0.0019 | 0.314 | 0.011 | 0.0435 | 0.0006 | 0.35 | 274 | 3 | 0.98 |

| Sample No. | Content (ppm) | Th/U | Isotope Ratio | Age/Ma | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th | U | 207Pb/206Pb | ±1σ | 207Pb/235U | ±1σ | 206Pb/238U | ±1σ | rho | 206Pb/238U | ±1σ | Concordance | ||

| D1009–1 | 226 | 279 | 0.81 | 0.0513 | 0.0023 | 0.297 | 0.013 | 0.0422 | 0.0006 | 0.31 | 266 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1009–2 | 77 | 142 | 0.54 | 0.0521 | 0.0025 | 0.298 | 0.015 | 0.0416 | 0.0006 | 0.30 | 263 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1009–3 | 96 | 161 | 0.59 | 0.0508 | 0.0024 | 0.291 | 0.013 | 0.0419 | 0.0005 | 0.28 | 264 | 3 | 0.98 |

| D1009–4 | 491 | 447 | 1.10 | 0.0518 | 0.0021 | 0.293 | 0.012 | 0.0409 | 0.0004 | 0.22 | 259 | 2 | 0.99 |

| D1009–5 | 343 | 326 | 1.05 | 0.0505 | 0.0057 | 0.294 | 0.035 | 0.0422 | 0.0014 | 0.27 | 267 | 8 | 0.98 |

| D1009–6 | 53 | 114 | 0.47 | 0.0536 | 0.0028 | 0.307 | 0.015 | 0.0424 | 0.0006 | 0.29 | 268 | 4 | 0.98 |

| D1009–7 | 96 | 168 | 0.57 | 0.0530 | 0.0033 | 0.306 | 0.017 | 0.0423 | 0.0007 | 0.30 | 267 | 4 | 0.98 |

| D1009–8 | 347 | 339 | 1.02 | 0.0519 | 0.0017 | 0.302 | 0.010 | 0.0421 | 0.0004 | 0.31 | 266 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1009–9 | 949 | 739 | 1.28 | 0.0518 | 0.0028 | 0.296 | 0.015 | 0.0415 | 0.0005 | 0.23 | 262 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1009–10 | 391 | 335 | 1.17 | 0.0522 | 0.0019 | 0.302 | 0.010 | 0.0420 | 0.0005 | 0.32 | 265 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1009–11 | 139 | 194 | 0.72 | 0.0517 | 0.0024 | 0.301 | 0.014 | 0.0424 | 0.0007 | 0.37 | 267 | 5 | 0.99 |

| D1009–12 | 189 | 256 | 0.74 | 0.0512 | 0.0053 | 0.300 | 0.031 | 0.0422 | 0.0011 | 0.24 | 266 | 7 | 0.99 |

| D1009–13 | 139 | 218 | 0.64 | 0.0516 | 0.0036 | 0.291 | 0.021 | 0.0408 | 0.0008 | 0.28 | 258 | 5 | 0.99 |

| D1009–14 | 395 | 338 | 1.17 | 0.0509 | 0.0057 | 0.298 | 0.033 | 0.0423 | 0.0008 | 0.17 | 267 | 5 | 0.99 |

| D1009–15 | 536 | 521 | 1.03 | 0.0505 | 0.0033 | 0.290 | 0.020 | 0.0414 | 0.0007 | 0.25 | 262 | 4 | 0.98 |

| D1009–16 | 82 | 193 | 0.42 | 0.0511 | 0.0046 | 0.289 | 0.022 | 0.0414 | 0.0017 | 0.54 | 261 | 11 | 0.98 |

| D1009–17 | 85 | 125 | 0.68 | 0.0519 | 0.0117 | 0.307 | 0.070 | 0.0427 | 0.0019 | 0.19 | 270 | 12 | 0.99 |

| D1009–18 | 162 | 206 | 0.79 | 0.0511 | 0.0029 | 0.295 | 0.017 | 0.0418 | 0.0008 | 0.34 | 264 | 5 | 0.99 |

| D1009–19 | 454 | 526 | 0.86 | 0.0511 | 0.0041 | 0.289 | 0.022 | 0.0409 | 0.0006 | 0.19 | 258 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1009–20 | 75 | 142 | 0.53 | 0.0523 | 0.0038 | 0.307 | 0.023 | 0.0424 | 0.0008 | 0.25 | 268 | 5 | 0.98 |

| D1009–21 | 1549 | 974 | 1.59 | 0.0517 | 0.0017 | 0.298 | 0.009 | 0.0417 | 0.0004 | 0.33 | 263 | 3 | 0.99 |

| D1009–22 | 181 | 242 | 0.75 | 0.0527 | 0.0038 | 0.308 | 0.021 | 0.0423 | 0.0011 | 0.38 | 267 | 7 | 0.98 |

| D1009–23 | 253 | 319 | 0.79 | 0.0531 | 0.0028 | 0.309 | 0.015 | 0.0425 | 0.0006 | 0.30 | 269 | 4 | 0.98 |

| D1009–24 | 126 | 201 | 0.63 | 0.0524 | 0.0029 | 0.309 | 0.016 | 0.0432 | 0.0007 | 0.31 | 272 | 4 | 0.99 |

| D1009–25 | 303 | 369 | 0.82 | 0.0515 | 0.0025 | 0.303 | 0.015 | 0.0426 | 0.0005 | 0.26 | 269 | 3 | 0.99 |

| Sample | t (Ma) | 176Yb/177Hf | 2σ | 176Lu/177Hf | 2σ | 176Hf/177Hf | 2σ | εHf(0) | εHf(t) | TDM1(Ma) | TDM2(Ma) | fLu/Hf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1010–1 | 269 | 0.1904 | 0.001392 | 0.0045 | 0.000036 | 0.283017 | 0.000028 | 8.66 | 13.78 | 367 | 411 | −0.86 |

| D1010–2 | 273 | 0.1350 | 0.000248 | 0.0032 | 0.000007 | 0.282922 | 0.000027 | 5.29 | 10.72 | 497 | 609 | −0.90 |

| D1010–3 | 278 | 0.1633 | 0.001019 | 0.0039 | 0.000016 | 0.282986 | 0.000031 | 7.57 | 12.98 | 408 | 469 | −0.88 |

| D1010–4 | 281 | 0.1046 | 0.000626 | 0.0025 | 0.000015 | 0.282855 | 0.000022 | 2.94 | 8.65 | 586 | 747 | −0.92 |

| D1010–5 | 273 | 0.0817 | 0.002045 | 0.0020 | 0.000052 | 0.282848 | 0.000019 | 2.69 | 8.33 | 588 | 761 | −0.94 |

| D1010–6 | 267 | 0.1604 | 0.001340 | 0.0038 | 0.000031 | 0.282997 | 0.000025 | 7.96 | 13.15 | 390 | 449 | −0.89 |

| D1010–7 | 278 | 0.0973 | 0.005348 | 0.0024 | 0.000113 | 0.282915 | 0.000032 | 5.05 | 10.73 | 496 | 612 | −0.93 |

| D1010–8 | 271 | 0.0754 | 0.000642 | 0.0018 | 0.000010 | 0.282835 | 0.000018 | 2.22 | 7.85 | 605 | 790 | −0.94 |

| D1010–9 | 270 | 0.1267 | 0.001804 | 0.0030 | 0.000047 | 0.282930 | 0.000022 | 5.60 | 10.99 | 482 | 589 | −0.91 |

| D1010–10 | 275 | 0.1484 | 0.008432 | 0.0035 | 0.000186 | 0.283018 | 0.000035 | 8.70 | 14.10 | 355 | 394 | −0.89 |

| D1010–11 | 271 | 0.1678 | 0.002820 | 0.0040 | 0.000079 | 0.283008 | 0.000031 | 8.35 | 13.60 | 375 | 424 | −0.88 |

| D1010–12 | 269 | 0.0655 | 0.001471 | 0.0017 | 0.000030 | 0.282814 | 0.000020 | 1.49 | 7.10 | 632 | 836 | −0.95 |

| D1010–13 | 277 | 0.0744 | 0.001918 | 0.0018 | 0.000041 | 0.282884 | 0.000021 | 3.97 | 9.73 | 533 | 675 | −0.95 |

| D1010–14 | 274 | 0.1209 | 0.001858 | 0.0028 | 0.000033 | 0.282931 | 0.000021 | 5.64 | 11.15 | 478 | 582 | −0.91 |

| D1010–15 | 273 | 0.0877 | 0.002103 | 0.0022 | 0.000055 | 0.282903 | 0.000021 | 4.62 | 10.25 | 511 | 639 | −0.94 |

| D1010–16 | 279 | 0.0656 | 0.000998 | 0.0017 | 0.000020 | 0.282836 | 0.000019 | 2.27 | 8.10 | 600 | 781 | −0.95 |

| D1010–17 | 272 | 0.1045 | 0.002526 | 0.0026 | 0.000061 | 0.282955 | 0.000023 | 6.46 | 11.99 | 440 | 528 | −0.92 |

| D1010–18 | 272 | 0.1714 | 0.001210 | 0.0041 | 0.000037 | 0.282990 | 0.000031 | 7.71 | 12.97 | 404 | 465 | −0.88 |

| D1010–19 | 274 | 0.1233 | 0.000998 | 0.0029 | 0.000014 | 0.282958 | 0.000021 | 6.57 | 12.07 | 439 | 523 | −0.91 |

| D1010–20 | 268 | 0.1554 | 0.001836 | 0.0037 | 0.000052 | 0.283013 | 0.000023 | 8.52 | 13.77 | 364 | 410 | −0.89 |

| D1010–21 | 274 | 0.1145 | 0.001298 | 0.0027 | 0.000033 | 0.282929 | 0.000022 | 5.55 | 11.08 | 480 | 587 | −0.92 |

| D1010–22 | 274 | 0.0881 | 0.000659 | 0.0022 | 0.000015 | 0.282894 | 0.000023 | 4.31 | 9.93 | 524 | 660 | −0.93 |

| D1010–23 | 274 | 0.1867 | 0.001864 | 0.0045 | 0.000034 | 0.283045 | 0.000030 | 9.65 | 14.87 | 324 | 345 | −0.86 |

| Sample | t (Ma) | 176Yb/177Hf | 2σ | 176Lu/177Hf | 2σ | 176Hf/177Hf | 2σ | εHf(0) | εHf(t) | TDM1(Ma) | TDM2(Ma) | fLu/Hf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1009–1 | 268 | 0.0712 | 0.000629 | 0.0019 | 0.000018 | 0.282805 | 0.000021 | 1.16 | 6.70 | 650 | 861 | −0.94 |

| D1009–2 | 267 | 0.0700 | 0.000941 | 0.0019 | 0.000023 | 0.282760 | 0.000023 | −0.43 | 5.11 | 714 | 962 | −0.94 |

| D1009–3 | 266 | 0.1538 | 0.002535 | 0.0038 | 0.000086 | 0.282869 | 0.000046 | 3.44 | 8.62 | 586 | 738 | −0.89 |

| D1009–4 | 262 | 0.1496 | 0.001478 | 0.0040 | 0.000057 | 0.282867 | 0.000039 | 3.35 | 8.41 | 593 | 747 | −0.88 |

| D1009–5 | 265 | 0.1184 | 0.003180 | 0.0031 | 0.000077 | 0.282914 | 0.000024 | 5.02 | 10.31 | 507 | 629 | −0.91 |

| D1009–6 | 267 | 0.0667 | 0.000736 | 0.0018 | 0.000018 | 0.282814 | 0.000023 | 1.50 | 7.05 | 635 | 839 | −0.94 |

| D1009–7 | 266 | 0.0598 | 0.002036 | 0.0017 | 0.000042 | 0.282837 | 0.000029 | 2.29 | 7.85 | 600 | 787 | −0.95 |

| D1009–8 | 258 | 0.0895 | 0.001324 | 0.0024 | 0.000062 | 0.282820 | 0.000036 | 1.71 | 6.97 | 636 | 837 | −0.93 |

| D1009–9 | 267 | 0.1224 | 0.003556 | 0.0033 | 0.000076 | 0.282862 | 0.000027 | 3.19 | 8.50 | 588 | 746 | −0.90 |

| D1009–10 | 262 | 0.0944 | 0.009014 | 0.0026 | 0.000262 | 0.282856 | 0.000048 | 2.97 | 8.29 | 586 | 756 | −0.92 |

| D1009–11 | 261 | 0.0885 | 0.000975 | 0.0027 | 0.000052 | 0.282813 | 0.000032 | 1.43 | 6.72 | 652 | 855 | −0.92 |

| D1009–12 | 270 | 0.0689 | 0.000587 | 0.0018 | 0.000011 | 0.282771 | 0.000021 | −0.03 | 5.57 | 696 | 934 | −0.95 |

| D1009–13 | 264 | 0.0965 | 0.001575 | 0.0025 | 0.000043 | 0.282841 | 0.000023 | 2.43 | 7.80 | 607 | 788 | −0.92 |

| D1009–14 | 258 | 0.1025 | 0.000753 | 0.0027 | 0.000022 | 0.282810 | 0.000021 | 1.34 | 6.56 | 656 | 863 | −0.92 |

| D1009–15 | 268 | 0.0750 | 0.000716 | 0.0020 | 0.000016 | 0.282786 | 0.000025 | 0.50 | 6.03 | 679 | 904 | −0.94 |

| D1009–16 | 263 | 0.1627 | 0.017353 | 0.0041 | 0.000404 | 0.282967 | 0.000050 | 6.89 | 11.97 | 441 | 522 | −0.88 |

| D1009–17 | 267 | 0.1365 | 0.005791 | 0.0036 | 0.000184 | 0.282767 | 0.000037 | −0.18 | 5.07 | 738 | 965 | −0.89 |

| D1009–18 | 269 | 0.1254 | 0.001122 | 0.0032 | 0.000021 | 0.282900 | 0.000020 | 4.54 | 9.88 | 530 | 659 | −0.90 |

| D1009–19 | 272 | 0.0738 | 0.000612 | 0.0019 | 0.000025 | 0.282792 | 0.000030 | 0.69 | 6.33 | 669 | 888 | −0.94 |

| D1009–20 | 269 | 0.1465 | 0.005506 | 0.0039 | 0.000181 | 0.282762 | 0.000044 | −0.37 | 4.84 | 754 | 980 | −0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Qiu, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Jiao, H. Geochronology and Geochemistry of Early–Middle Permian Intrusive Rocks in the Southern Greater Xing’an Range, China: Constraints on the Tectonic Evolution of the Paleo-Asian Ocean. Minerals 2025, 15, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121288

Zhang H, Yang X, Huang X, Qiu L, Li G, Zhang Y, Chen W, Jiao H. Geochronology and Geochemistry of Early–Middle Permian Intrusive Rocks in the Southern Greater Xing’an Range, China: Constraints on the Tectonic Evolution of the Paleo-Asian Ocean. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121288

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Haihua, Xiaoping Yang, Xin Huang, Liang Qiu, Gongjian Li, Yujin Zhang, Wei Chen, and Haiwei Jiao. 2025. "Geochronology and Geochemistry of Early–Middle Permian Intrusive Rocks in the Southern Greater Xing’an Range, China: Constraints on the Tectonic Evolution of the Paleo-Asian Ocean" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121288

APA StyleZhang, H., Yang, X., Huang, X., Qiu, L., Li, G., Zhang, Y., Chen, W., & Jiao, H. (2025). Geochronology and Geochemistry of Early–Middle Permian Intrusive Rocks in the Southern Greater Xing’an Range, China: Constraints on the Tectonic Evolution of the Paleo-Asian Ocean. Minerals, 15(12), 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121288