Research on Digital Core Characterization and Pore Structure Control Factors of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in the Fuyu Oil Layer of the Upper Cretaceous in the Bayan Chagan Area of the Northern Songliao Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

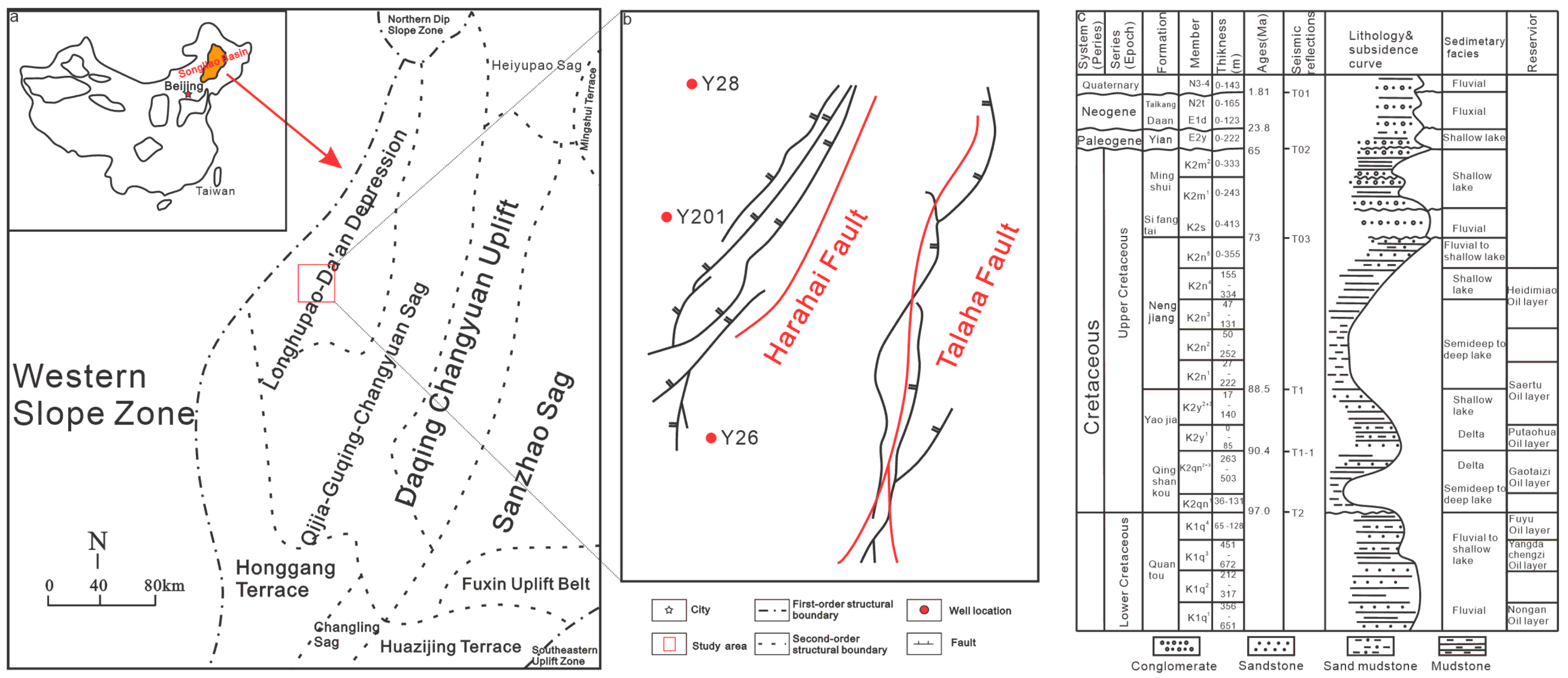

2. Regional Geological Overview

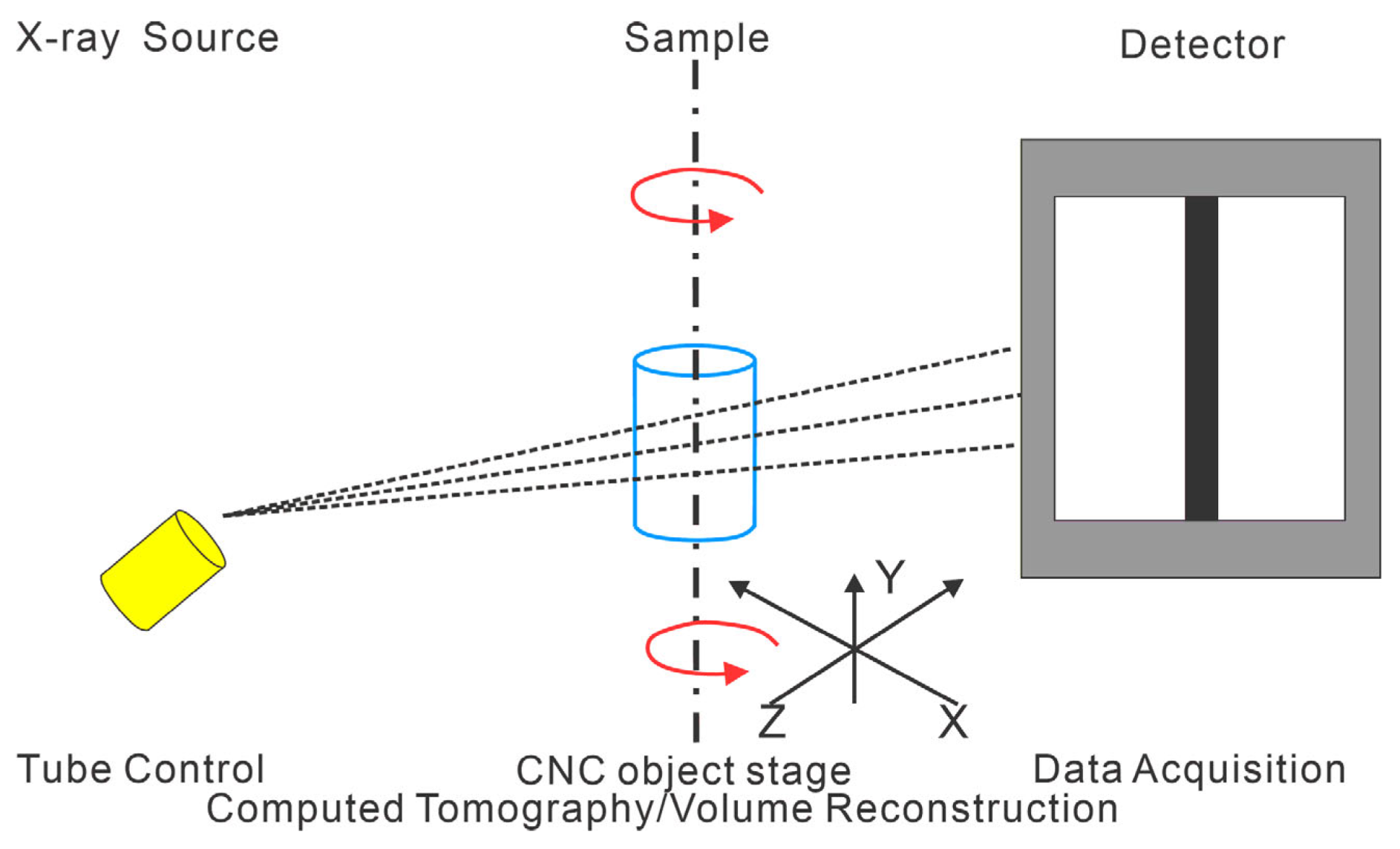

3. Samples and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Petrological Characteristics of Reservoirs

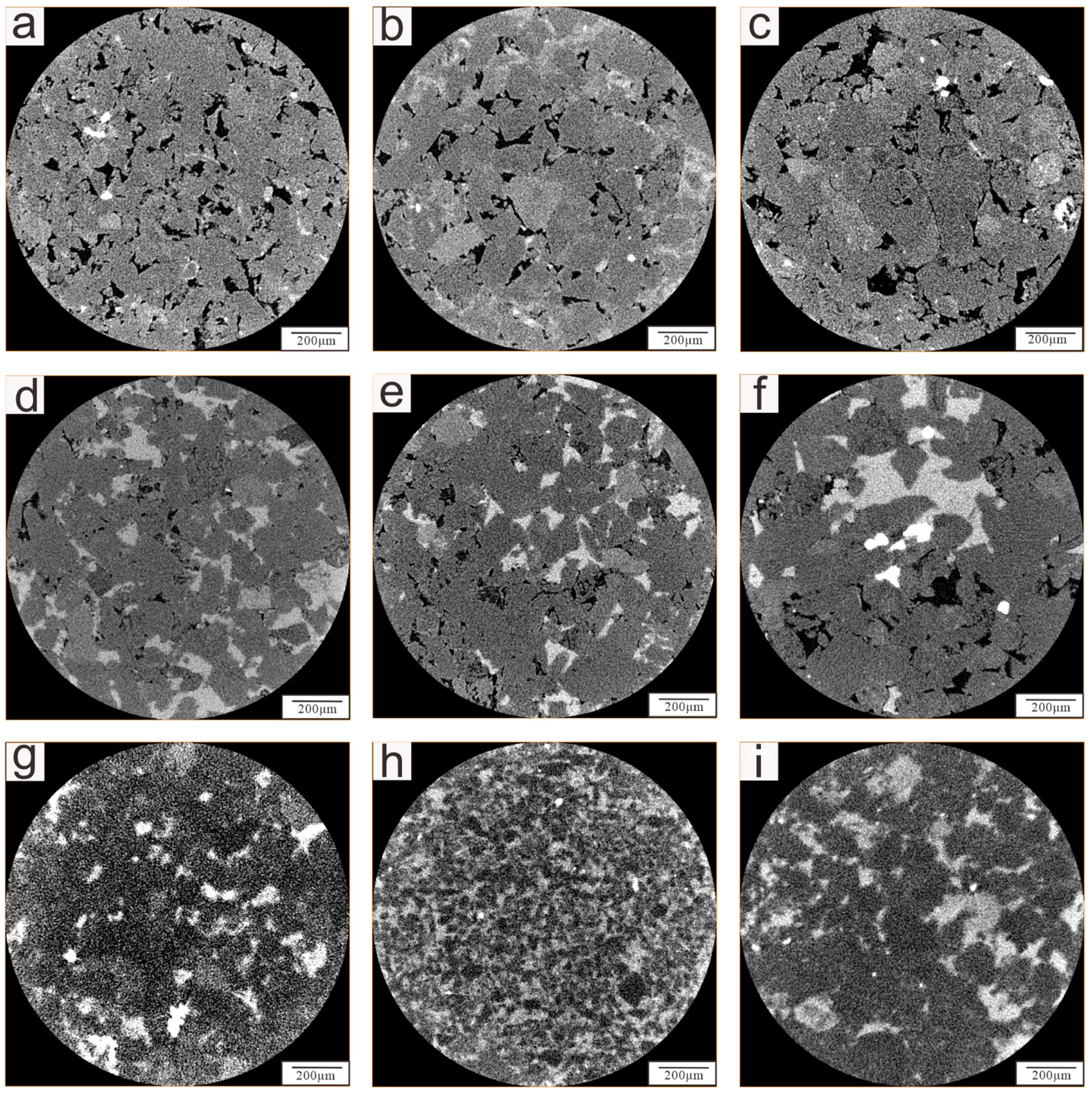

4.2. Reservoir Physical Property Characteristics and Classification

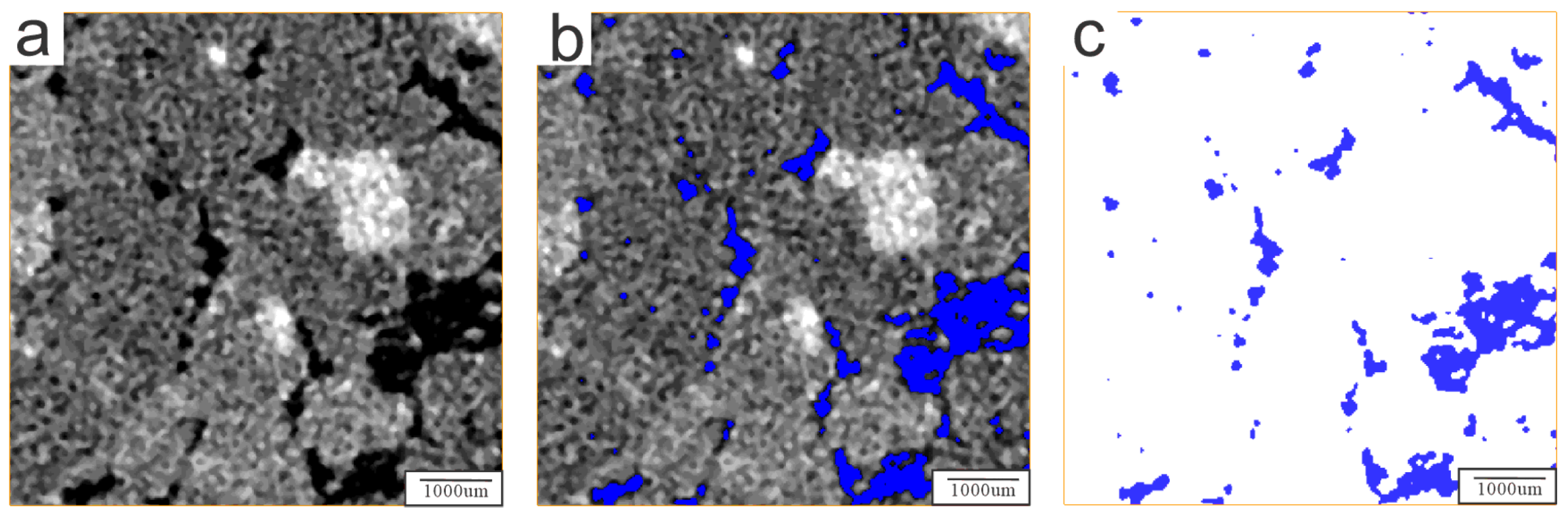

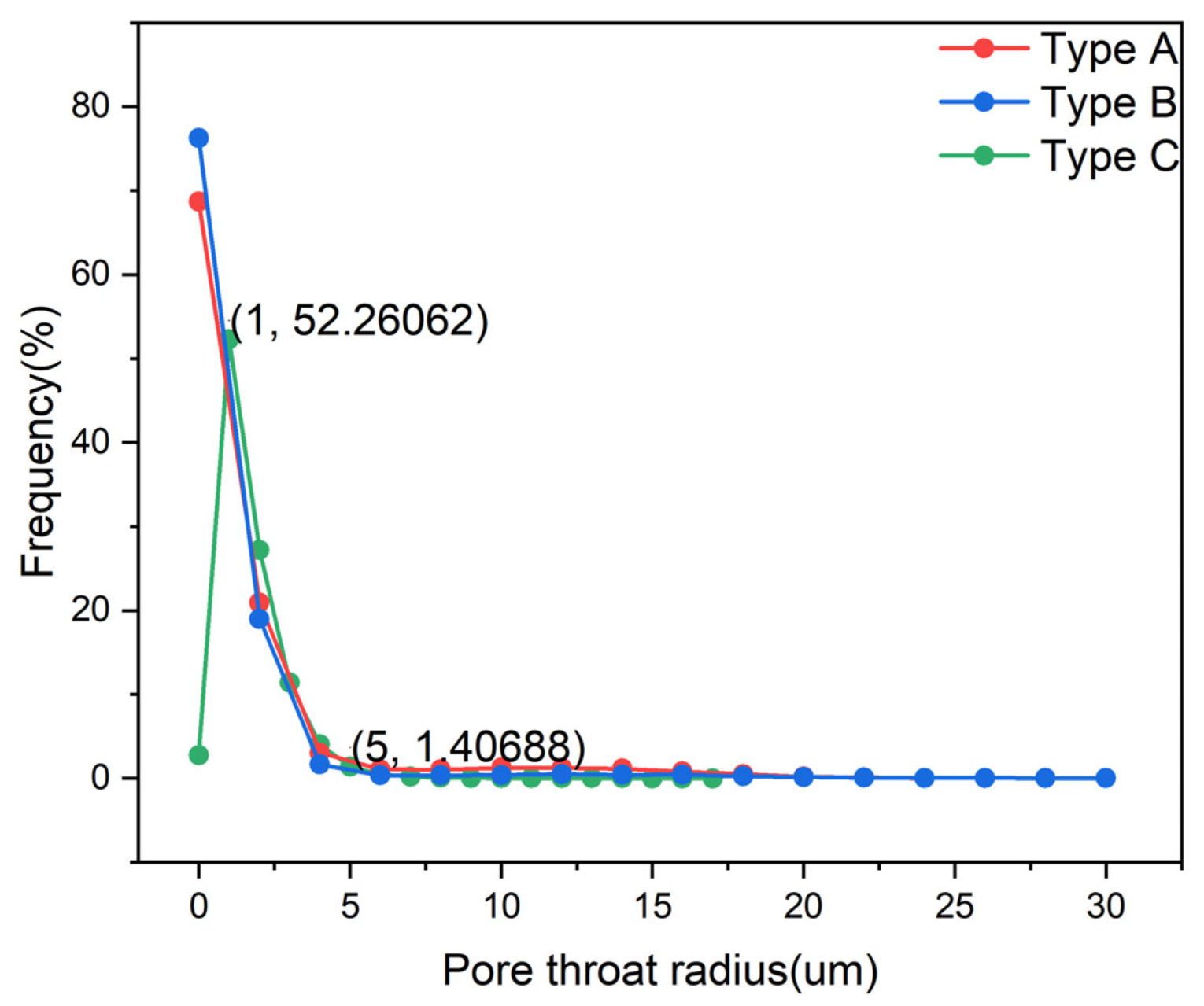

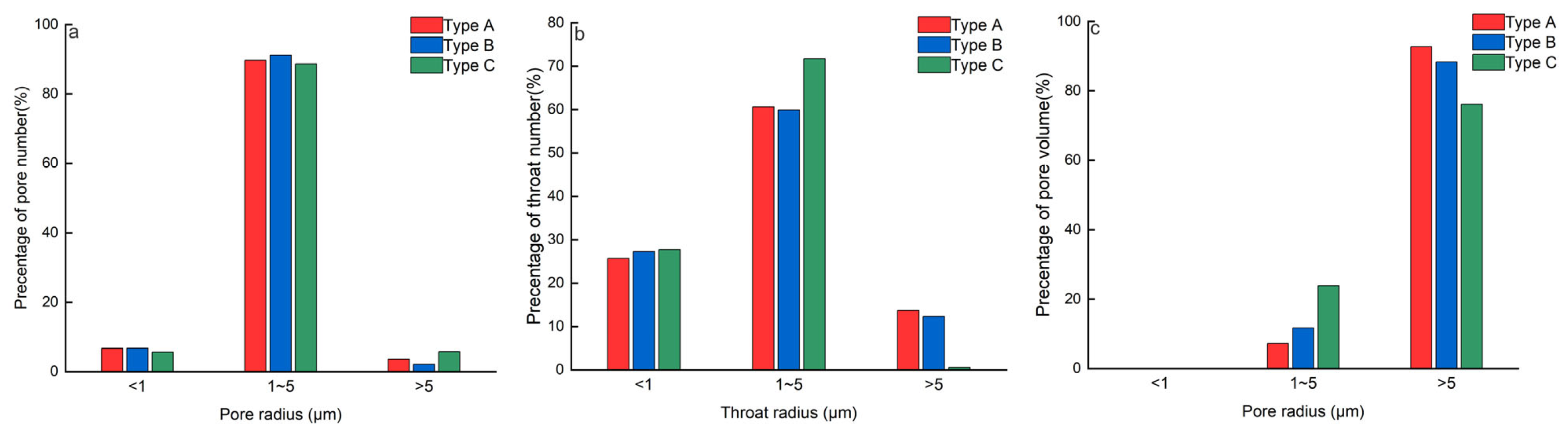

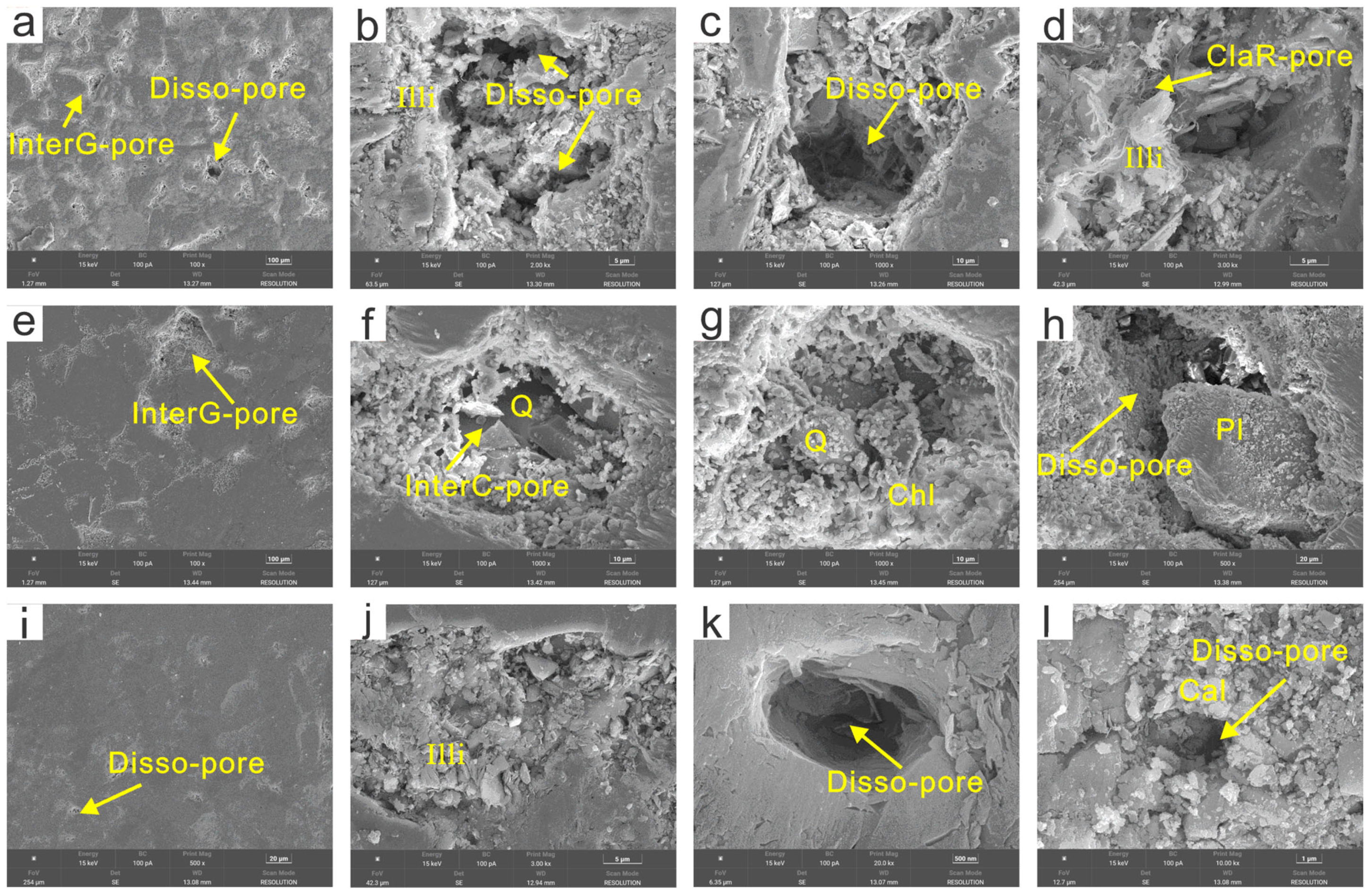

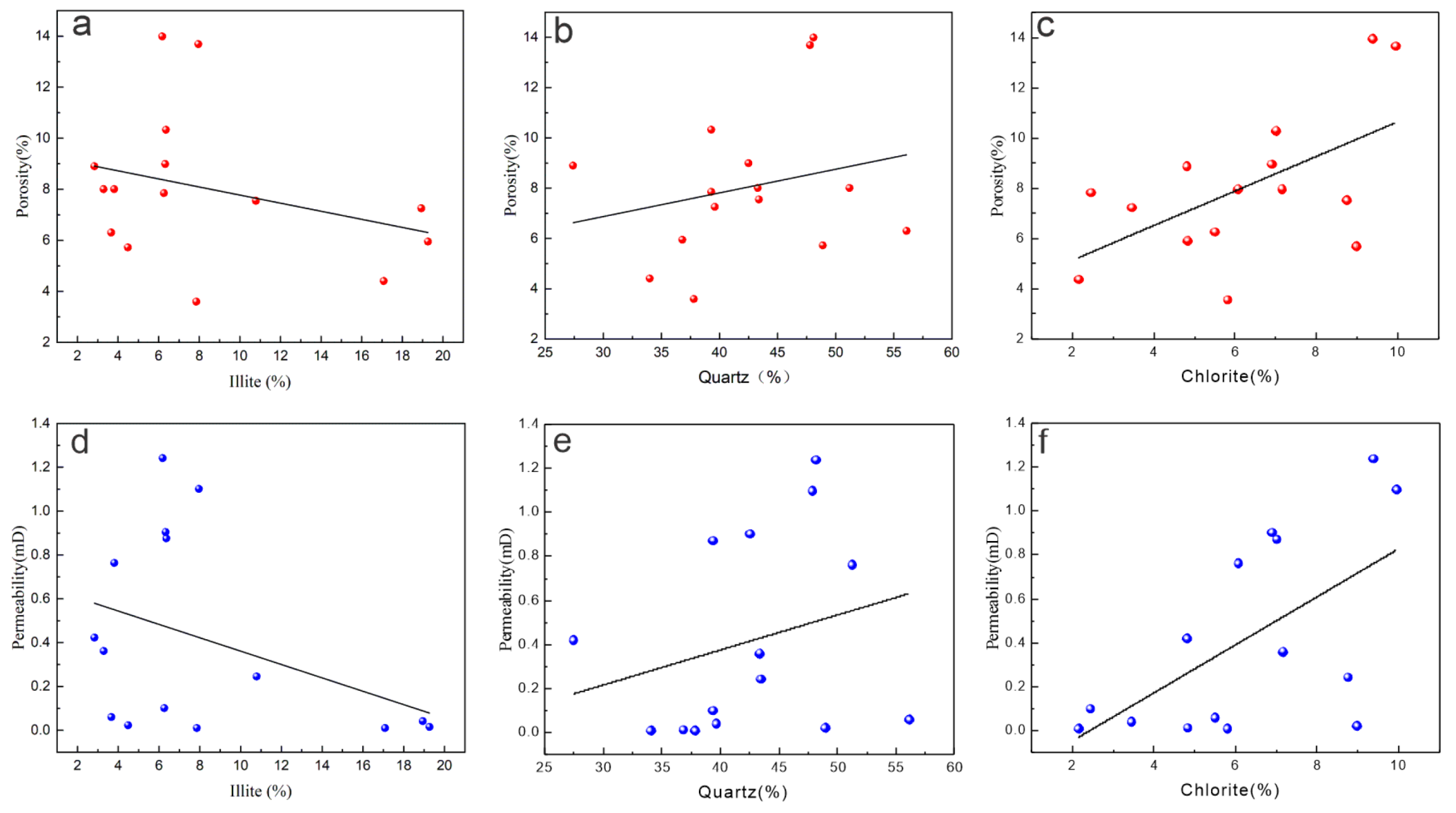

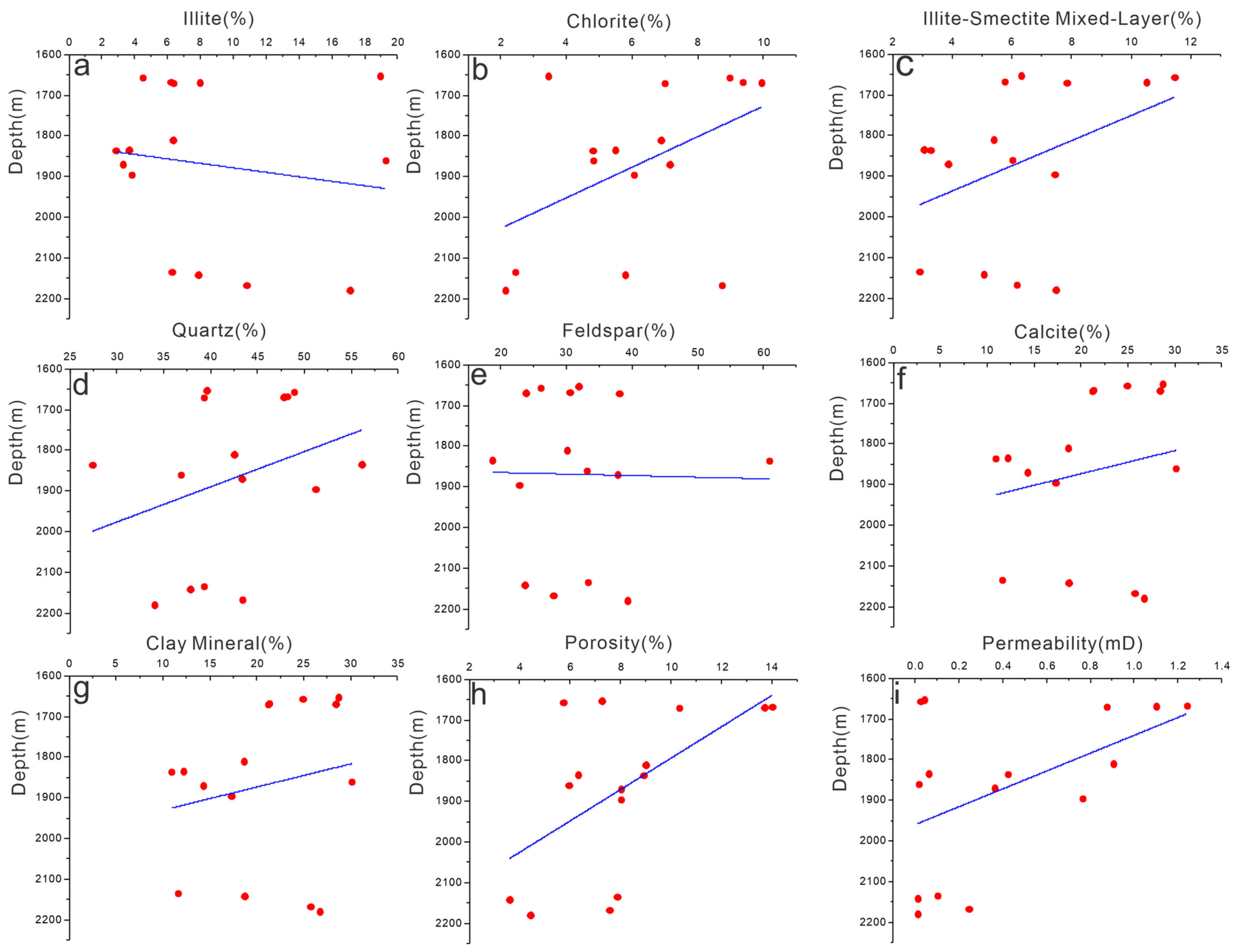

4.3. Reservoir Pore Structure Characteristics

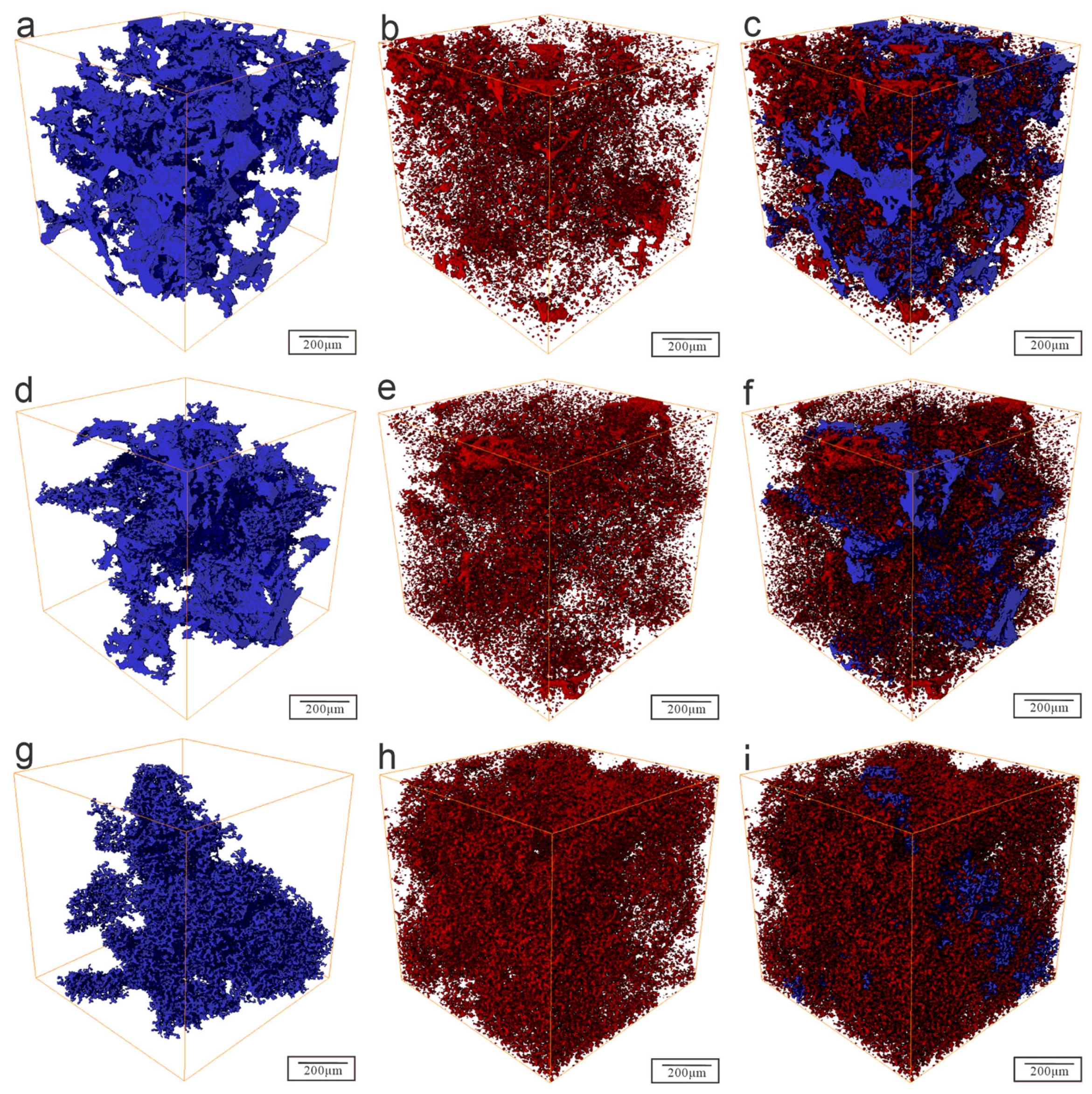

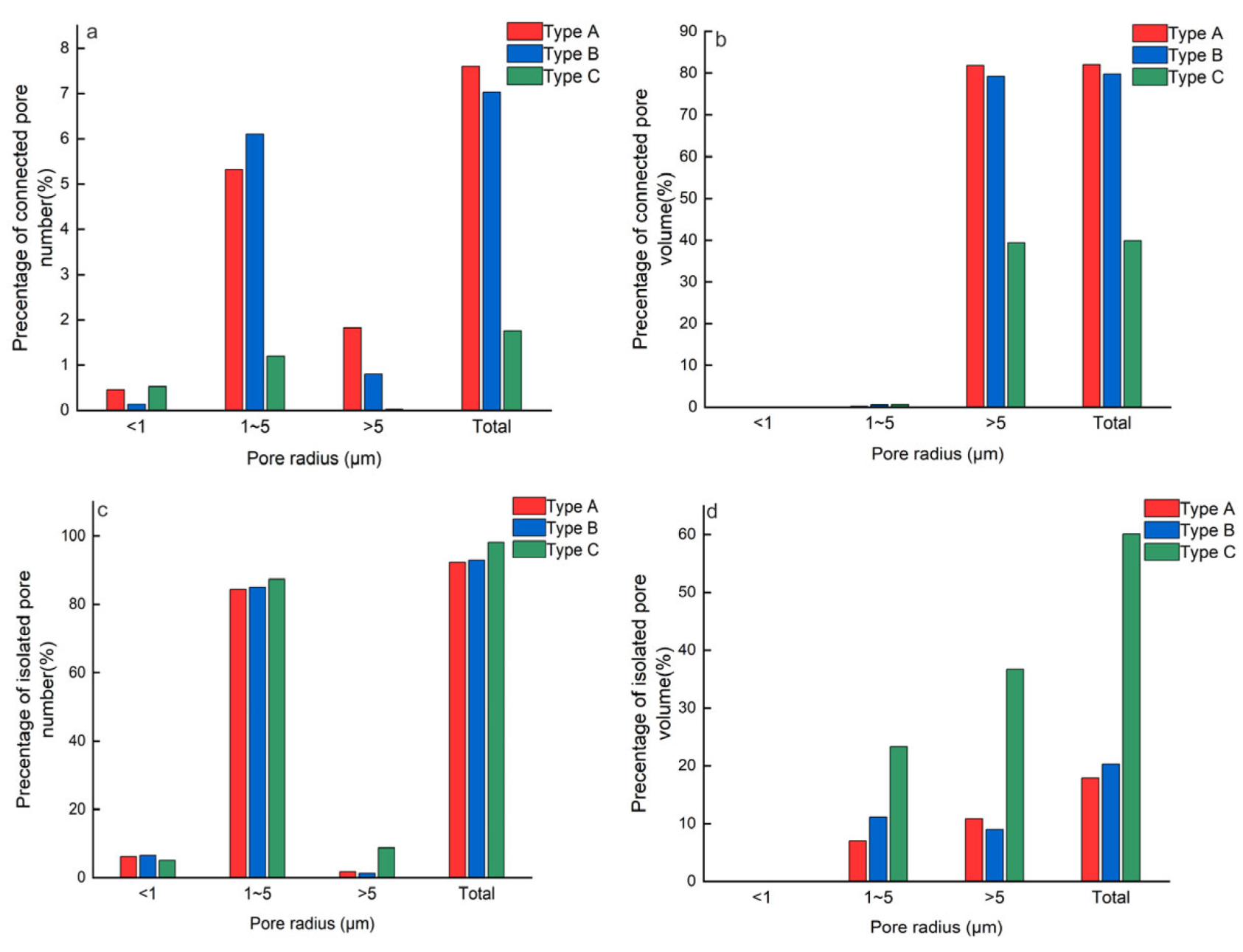

4.4. Reservoir Connectivity Characteristics

4.5. Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of Reservoirs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merryn, T.; Tristan, P.; Barbara Herr, H.; Nick, P. Deliberating the perceived risks, benefits, and societal implications of shale gas and oil extraction by hydraulic fracturing in the US and UK. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Zhang, D.; Huang, H.; Wang, S.; Meng, Y. Advances in Unconventional Oil and Gas. Energies 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. From tight oil & gas to shale oil & gas—An approach to developing unconventional oil & gas in China. Int. Pet. Econ. 2012, 3, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Zou, C.; Jin, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wu, S.; Guo, Z. Development characteristics and orientation of tight oil and gas in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Gong, D.; Hong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, F.; Yan, Z.; Li, H. Sichuan super gas basin in southwest China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhao, M.; Feng, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Ding, J.; Chen, Q. Intelligent recognition of “geological-engineering” sweet spots in tight sandstone reservoirs—An application to a tight gas reservoir in Ordos Basin, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1535883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhua, W.; Qi’an, M.; Jiangping, L.; Xuefeng, B.; Jianliang, P.; Tao, X.; Jia, W. Tight Oil Exploration in Northern Songliao Basin. Zhongguo Shiyou Kantan 2015, 20, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, J.J. Enhanced Oil Recovery in Shale and Tight Reservoirs; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.J.; Stephen, M.T. Overview of Impacts from Tight Oil and Shale Gas Resource Development. In Environmental Considerations Associated with Hydraulic Fracturing Operations: Adjusting to the Shale Revolution in a Green World; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremy, B.; Robert, K. Shale Gas, Tight Oil, Shale Oil and Hydraulic Fracturing. In Future Energy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Sun, Z.; Gao, Z.; Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Ren, D. Quantitative Characterization of Micro-Scale Pore-Throat Heterogeneity in Tight Sandstone Reservoir. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chao, Z.; Feng, H.; Hao, J. Characterization Method of Tight Sandstone Reservoir Heterogeneity and Tight Gas Accumulation Mechanism, Jurassic Formation, Sichuan Basin, China. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 9420835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xie, R.; Jin, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Fan, W. Investigation on the Pore Structure and Multifractal Characteristics of Tight Sandstone Using Nitrogen Gas Adsorption and Mercury Injection Capillary Pressure Experiments. Energy Fuels 2021, 36, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Xie, R.; Xiao, L. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Characterization of Petrophysical Properties in Tight Sandstone Reservoirs. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2020, 125, e2019JB018716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Research on Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics of Tight Sandstone Reservoir Based on High-Pressure Mercury Injection Method. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2023, 11, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.; Hua, H.; Wang, X. Characterization of pore structure and reservoir properties of tight sandstone with CTS, SEM, and HPMI: A case study of the tight oil reservoir in fuyu oil layers of Sanzhao Sag, Songliao basin, NE China. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 1053919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Zeng, J.; Jiang, S.; Feng, S.; Feng, X.; Guo, Z.; Teng, J. Heterogeneity of reservoir quality and gas accumulation in tight sandstone reservoirs revealed by pore structure characterization and physical simulation. Fuel 2019, 253, 1300–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Horne, R.N.; Cai, J.; Yao, J. Recent advances on fluid flow in porous media using digital core analysis technology. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 9, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulquadri, O.A.; Mohamed Soufiane, J.; Mohammad, A.; Daniel, M.; Fadi, H.N.; Fateh, B.; Emad, W.A.-S.; Osama Al, J. Pore to core plug scale characterization of porosity and permeability heterogeneities in a Cretaceous carbonate reservoir using laboratory measurements and digital rock physics, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 172, 107214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Yan, Q. Detailed characterization of micronano pore structure of tight sandstone reservoir space in three dimensional space: A case study of the Gao 3 and Gao 4 members of Gaotaizi reservoir in the Qijia area of the Songliao basin. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zheng, R.; Li, H. Quantitative Characterization of Tight Rock Microstructure of Digital Core. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 3554563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, D.; Ma, S.; Duan, W.; Zhang, Y. Densification and Fracture Type of Desert in Tight Oil Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Fuyu Tight Oil Reservoir in the Sanzhao Depression, Songliao Basin. Lithosphere 2021, 2021, 2609923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; He, J.; Liu, P.; Liu, J.; Yan, G.; Yao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, C. Oil Charging Power Simulation and Tight Oil Formation of Fuyu Oil Layer in Sanzhao Area, Songliao Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 825548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Qiao, W.; Chen, X.; Hu, J.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, W.; Gu, H.; Li, Y. Seismic Response Characteristics of Tight Oil Sweet Spots in Fuyu Reservoir Under the Source in the Northern Songliao Basin. In Proceedings of the International Field Exploration and Development Conference 2023, Beijing, China, 24–26 September 2023; Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Niu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Fu, H.; Wang, Z. Microscopic pore-throat grading evaluation in a tight oil reservoir using machine learning: A case study of the Fuyu oil layer in Bayanchagan area, Songliao Basin central depression. Earth Sci. Inform. 2021, 14, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Q.; Yin, X. A comparative analysis of mercury intrusion and nitrogen adsorption methods for multifractal characterization of shale reservoirs in northern Songliao Basin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, P.; Sun, L.; He, T. Nanoscale pore structure and fractal characteristics of lacustrine shale: A case study of the Upper Cretaceous Qingshankou shales, Southern Songliao Basin, China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y. Study on the structural characteristics of the Yangdachengzi oil layer in the Quantou Formation, ZY block, central depression, Songliao Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1132837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, S.; Fang, H. Study on sedimentary facies and prediction of favorable reservoir areas in the Fuyu reservoir in the Bayanchagan area. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X. Study on Depositional Elements and Sandstone Body Development Characteristics Under High-Resolution Sequence Framework of the Fuyu Oil Layer in Bayanchagan Area. SPE J. 2024, 30, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Feng, C.; Wang, G.; Jia, N.; Li, H.; Shi, X. Study on the Quantitative Characterization and Heterogeneity of Pore Structure in Deep Ultra-High Pressure Tight Glutenite Reservoirs. Minerals 2023, 13, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Fu, D.; Wang, H.; Lei, X.; Liu, Z.; Wei, L.; Liu, Y. The impact of multistage fluid and diagenetic environmental coupling on the development of deep clastic rock reservoirs: A case from the Zhuhai Formation, Wenchang A Sag, Zhujiangkou Basin. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2025, 44, 01445987251379955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.; Er, C.; Bai, Y.; Wu, W. Diagenesis of tight sandstone and its influence on reservoir properties: A case study of Fuyu reservoirs in Songliao Basin, China. Unconv. Resour. 2022, 3, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Tang, X.; Xiao, H.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Jiao, Y. Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of Effective Seepage Channels in the Tight Reservoir of the Fuyu Oil Layer in the Northern Part of the Songliao Basin. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 9660–9675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Tian, J.; Yang, T.; Ren, Z.; Gong, L. Diagenetic Evolution and Its Impact on Reservoir Quality of Tight Sandstones: A Case Study of the Triassic Chang-7 Member, Ordos Basin, Northwest China. Energies 2023, 16, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, J.; Worden, R.H.; Utley, J.E.; Brostrøm, C.; Martinius, A.W.; Lawan, A.Y.; Al-Hajri, A.I. Origin and distribution of grain-coating and pore-filling chlorite in deltaic sandstones for reservoir quality assessment. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 134, 105326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, H.W.; Joshua, G.; Luke, J.W.; James, E.P.U.; Lawan, A.Y.; Muhammed, D.D.; Simon, N.; Peter, A. Chlorite in sandstones. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 204, 103105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.; Lin, M.; Liu, L.; Jia, L. The effect of chlorite rims on reservoir quality in Chang 7 sandstone reservoirs in the Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 158, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Number | Well Number | Whole Rock Quantitative Analysis (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Amount of Clay Minerals | Quartz | Potassium Feldspar | Plagioclase | Calcite | ||

| 1 | Y26 | 11.6 | 39.3 | 4.8 | 28.5 | 15.8 |

| 2 | Y26 | 18.7 | 37.8 | 3.3 | 20.3 | 19.9 |

| 3 | Y26 | 25.7 | 43.4 | 7.8 | 20.2 | 2.8 |

| 4 | Y26 | 26.7 | 34 | 7.5 | 31.8 | 0 |

| 5 | Y28 | 28.7 | 39.6 | 4.1 | 27.7 | 0 |

| 6 | Y28 | 24.9 | 48.9 | 3.4 | 22.7 | 0 |

| 7 | Y28 | 21.3 | 48.1 | 3 | 27.5 | 0 |

| 8 | Y28 | 28.4 | 47.8 | 2.6 | 21.2 | 0 |

| 9 | Y28 | 21.2 | 39.3 | 5.4 | 32.6 | 1.4 |

| 10 | Y201 | 18.6 | 42.5 | 3.4 | 26.7 | 8.8 |

| 11 | Y201 | 12.2 | 56.1 | 3.7 | 15 | 12.9 |

| 12 | Y201 | 10.9 | 27.4 | 12.8 | 48.1 | 0.9 |

| 13 | Y201 | 30.1 | 36.8 | 2.6 | 30.5 | 0 |

| 14 | Y201 | 14.3 | 43.3 | 6.1 | 31.7 | 4.6 |

| 15 | Y201 | 17.3 | 51.2 | 4 | 18.8 | 8.7 |

| Sample No. | Well No. | Total Clay Content (%) | I/S Mixed-Layer (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illite (I) (%) | Chlorite (C) (%) | I/S Ratio | Smectite (S) (%) | Illite (I) (%) | ||

| 1 | Y26 | 54 | 21 | 25 | 15 | 85 |

| 2 | Y26 | 42 | 31 | 27 | 20 | 80 |

| 3 | Y26 | 42 | 34 | 24 | 20 | 80 |

| 4 | Y26 | 64 | 8 | 28 | 15 | 85 |

| 5 | Y28 | 66 | 12 | 22 | 25 | 75 |

| 6 | Y28 | 18 | 36 | 46 | 25 | 75 |

| 7 | Y28 | 29 | 44 | 27 | 30 | 70 |

| 8 | Y28 | 28 | 35 | 37 | 30 | 70 |

| 9 | Y28 | 30 | 33 | 37 | 30 | 70 |

| 10 | Y201 | 34 | 37 | 29 | 25 | 75 |

| 11 | Y201 | 30 | 45 | 25 | 25 | 75 |

| 12 | Y201 | 26 | 44 | 30 | 25 | 75 |

| 13 | Y201 | 64 | 16 | 20 | 25 | 75 |

| 14 | Y201 | 23 | 50 | 27 | 20 | 80 |

| 15 | Y201 | 22 | 35 | 43 | 25 | 75 |

| Sample No | Well No | Depth (m) | Lithology | Porosity (%) | Permeability (mD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Y26 | 2135.01 | Argillaceous Siltstone | 7.85 | 0.10 |

| 2 | Y26 | 2140.97 | Argillaceous Siltstone | 3.59 | 0.0098 |

| 3 | Y26 | 2166.42 | Siltstone | 7.54 | 0.24 |

| 4 | Y26 | 2179.61 | Siltstone | 4.40 | 0.01 |

| 5 | Y28 | 1653.01 | Siltstone | 7.25 | 0.042 |

| 6 | Y28 | 1656.52 | Siltstone | 5.72 | 0.023 |

| 7 | Y28 | 1667.85 | Medium-grained Sandstone | 13.98 | 1.24 |

| 8 | Y28 | 1669.05 | Medium-grained Sandstone | 13.68 | 1.10 |

| 9 | Y28 | 1670.53 | Fine-grained Sandstone | 10.32 | 0.87 |

| 10 | Y201 | 1809.85 | Fine-grained Sandstone | 8.99 | 0.90 |

| 11 | Y201 | 1834.90 | Fine-grained Sandstone | 6.30 | 0.060 |

| 12 | Y201 | 1835.50 | Fine-grained Sandstone | 8.90 | 0.42 |

| 13 | Y201 | 1860.60 | Siltstone | 5.94 | 0.015 |

| 14 | Y201 | 1869.83 | Fine-grained Sandstone | 8.006 | 0.36 |

| 15 | Y201 | 1895.09 | Medium-grained Sandstone | 8.006 | 0.76 |

| Reservoir Type | Sample Number | Porosity% | Penetration Rate mD | Pore Quantity | Average Pore Radius μm | Average Pore Volume μm/cm3 | Allocation Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | 8 | 13.685 | 1.1014 | 14,230 | 2.57 | 878.696 | 0.45 |

| 9 | 10.326 | 0.8754 | 14,154 | 2.27 | 555.946 | 0.31 | |

| 10 | 8.992 | 0.9046 | 4364 | 2.78 | 1189.601 | 0.27 | |

| Type B | 15 | 8.006 | 0.7636 | 9062 | 2.02 | 563.688 | 0.20 |

| 12 | 8.901 | 0.4231 | 6878 | 1.99 | 168.811 | 0.14 | |

| 11 | 6.3 | 0.0601 | 5867 | 2.31 | 203.231 | 0.11 | |

| Type C | 1 | 7.851 | 0.101 | 65,535 | 2.02 | 61.514 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 3.594 | 0.0098 | 60,272 | 2.05 | 82.112 | 0.03 | |

| 3 | 7.548 | 0.2453 | 65,535 | 2.15 | 86.092 | 0.02 |

| Reservoir Type | Classification | Micropore | Mesopore | Macropore | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | Pore radius (μm) | <1 | 1~5 | >5 | |

| Number | 2173 | 29,298 | 1181 | 32,652 | |

| Percentage of pore number (%) | 6.66 | 89.71 | 3.63 | 100.00 | |

| Percentage of pore volume (%) | 0.04 | 7.25 | 92.71 | 100.00 | |

| Number of connected pores | 1345 | 1859 | 584 | 2479 | |

| Percentage of connected pore number (%) | 0.46 | 5.32 | 1.82 | 7.60 | |

| Percentage of connected pore volume (%) | 0 | 0.23 | 81.83 | 82.06 | |

| Number of isolated pores | 2137 | 27,439 | 597 | 30,173 | |

| Percentage of isolated pore number (%) | 6.20 | 84.39 | 1.81 | 92.40 | |

| Percentage of isolated pore volume (%) | 0.04 | 7.02 | 10.88 | 17.94 |

| Reservoir Type | Classification | Micropore | Mesopore | Macropore | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type B | Pore radius (μm) | <1 | 1~5 | >5 | |

| Number | 3123 | 42,279 | 982 | 46,384 | |

| Percentage of pore number (%) | 6.74 | 91.14 | 2.12 | 100.00 | |

| Percentage of pore volume (%) | 0.05 | 11.68 | 88.27 | 100.00 | |

| Number of connected pores | 52 | 2834 | 374 | 3260 | |

| Percentage of connected pore number (%) | 0.13 | 6.1 | 0.80 | 7.03 | |

| Percentage of connected pore volume (%) | 0 | 0.51 | 79.22 | 79.73 | |

| Number of isolated pores | 3071 | 39,445 | 608 | 43,124 | |

| Percentage of isolated pore number (%) | 6.58 | 85.04 | 1.32 | 92.97 | |

| Percentage of isolated pore volume (%) | 0.05 | 11.17 | 9.05 | 20.27 |

| Reservoir Type | Classification | Micropore | Mesopore | Macropore | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type C | Pore radius (μm) | <1 | 1~5 | >5 | |

| Number | 2905 | 45,724 | 2984 | 51,613 | |

| Percentage of pore number (%) | 5.63 | 88.59 | 5.78 | 100.00 | |

| Percentage of pore volume (%) | 0.06 | 23.85 | 76.09 | 100.00 | |

| Number of connected pores | 273 | 618 | 16 | 907 | |

| Percentage of connected pore number (%) | 0.53 | 1.2 | 0.03 | 1.76 | |

| Percentage of connected pore volume (%) | 0.01 | 0.53 | 39.37 | 39.91 | |

| Number of isolated pores | 2632 | 45,106 | 2968 | 50,706 | |

| Percentage of isolated pore number (%) | 5.10 | 87.39 | 5.75 | 98.24 | |

| Percentage of isolated pore volume (%) | 0.05 | 23.32 | 36.72 | 60.09 |

| Reservoir Type | Classification | Fine Throat | Medium Throat | Coarse Throat | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pore throat radius (μm) | <1 | 1~5 | >5 | ||

| Type A | Number | 1514 | 3574 | 807 | 5895 |

| Percentage of throat number (%) | 25.68 | 60.63 | 13.69 | 100.00 | |

| Type B | Number | 1999 | 4225 | 876 | 7100 |

| Percentage of throat number (%) | 27.27 | 59.92 | 12.34 | 100.00 | |

| Type C | Number | 1749 | 4529 | 36 | 6314 |

| Percentage of throat number (%) | 27.71 | 71.72 | 0.57 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Fu, H.; Wang, Z. Research on Digital Core Characterization and Pore Structure Control Factors of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in the Fuyu Oil Layer of the Upper Cretaceous in the Bayan Chagan Area of the Northern Songliao Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121289

Li Y, Liu Q, Fu H, Wang Z. Research on Digital Core Characterization and Pore Structure Control Factors of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in the Fuyu Oil Layer of the Upper Cretaceous in the Bayan Chagan Area of the Northern Songliao Basin. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121289

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yilin, Qi Liu, Hang Fu, and Zeqiang Wang. 2025. "Research on Digital Core Characterization and Pore Structure Control Factors of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in the Fuyu Oil Layer of the Upper Cretaceous in the Bayan Chagan Area of the Northern Songliao Basin" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121289

APA StyleLi, Y., Liu, Q., Fu, H., & Wang, Z. (2025). Research on Digital Core Characterization and Pore Structure Control Factors of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in the Fuyu Oil Layer of the Upper Cretaceous in the Bayan Chagan Area of the Northern Songliao Basin. Minerals, 15(12), 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121289