Minerals as Windows into Habitability on Lava Tube Basalts: A Biogeochemical Study at Lava Beds National Monument, CA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

- (1)

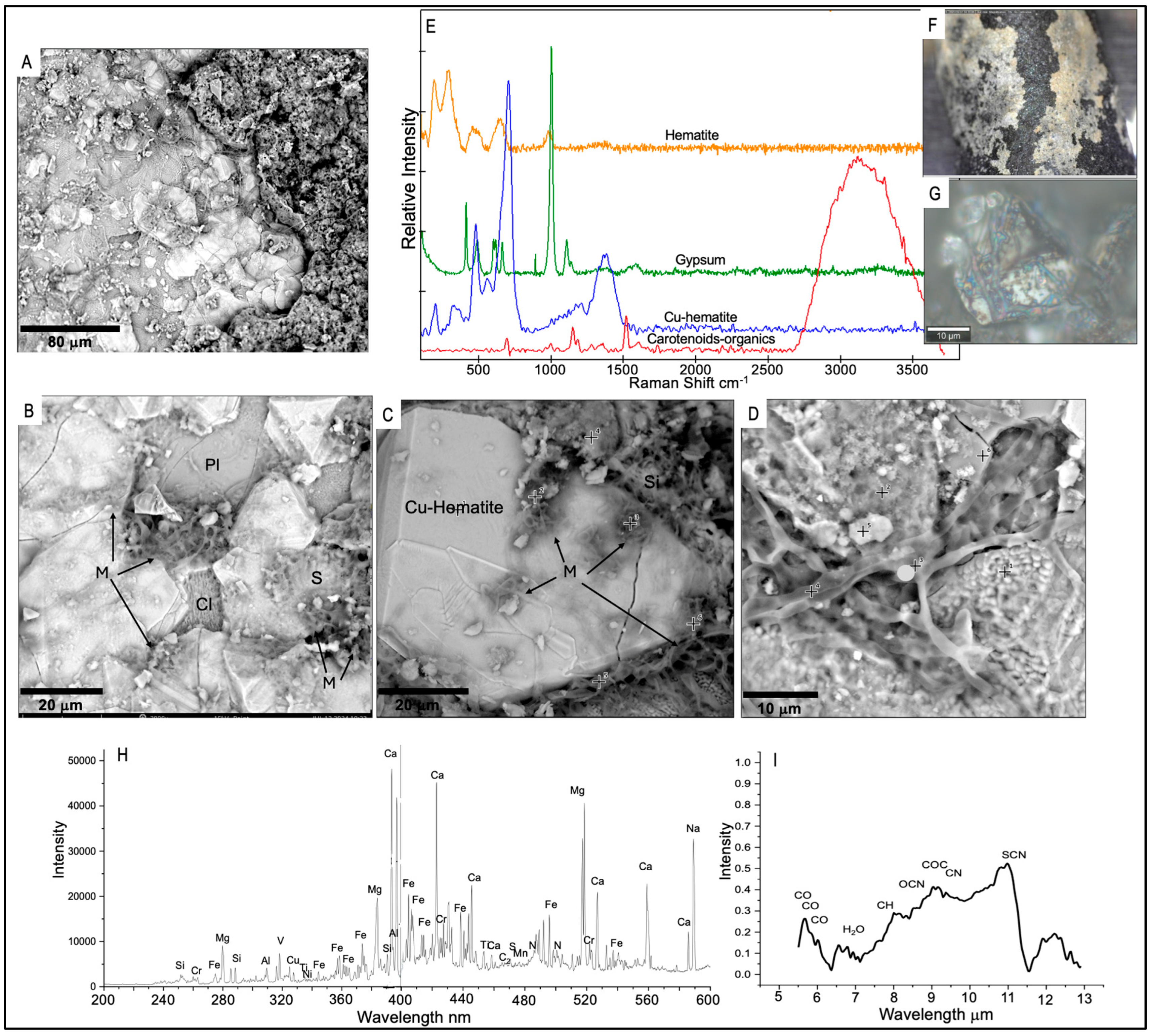

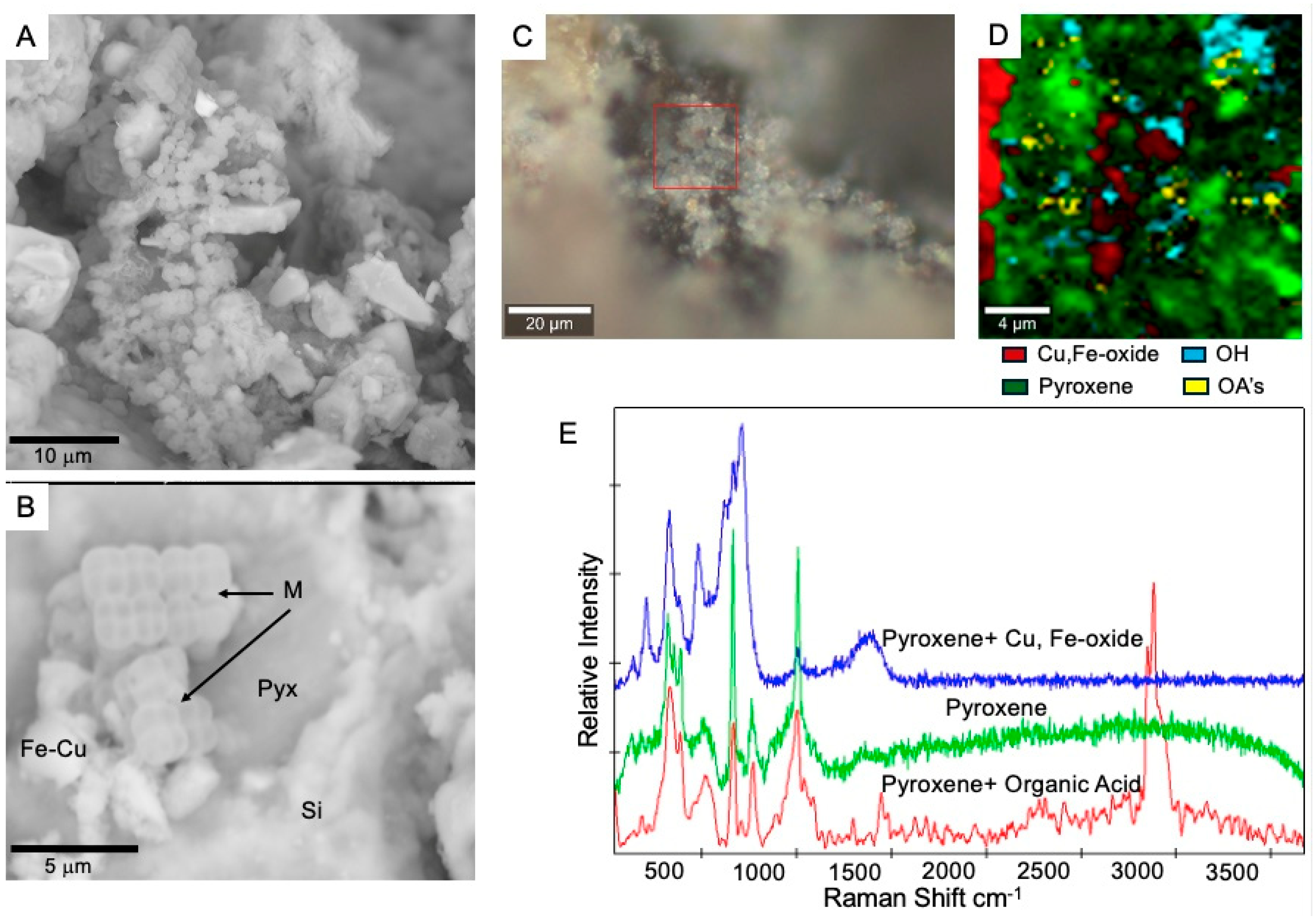

- The predominant secondary minerals we identified in the crusts and coatings of the lava tube samples were amorphous silicates, derived from basalt-cave water interactions. These precipitates were enriched in Al, Mg, Ca, Na, and Fe with lesser amounts of Cu, Cr, and V. Much of the microbial material we observed was permineralized with amorphous silica, which was enriched in C, N, P, and S.

- (2)

- Cryptocrystalline gypsum was identified at the interface between the basalts and amorphous silicate crusts. Sulfate and nitrate metabolisms indicated by some of the genes and pathways we identified, along with the S-bearing organic compounds detected as pyrolysis products or observed from Raman and LIBS analyses, and the spatial relationships between the microbial materials and the gypsum collectively indicate an active S-cycle in both lava tubes. It is not clear, however, if the microbes are actively inducing the sulfate formation or if they are utilizing abiotically formed sulfates as an energy source.

- (3)

- Clay minerals were also identified at interfaces between the basalts and amorphous silica crusts with Raman, SEM/EDS, and LIBS, often in areas where the cryptocrystalline gypsum was identified. The spatial relationships between the microbial materials and the clays and altered textures on basalt minerals observed by SEM suggest that the formation of these clays may be related to changes in local pH induced by microbial activity. We note that clay minerals were not detected with XRD, highlighting the importance of combining complementary techniques.

- (4)

- Large Fe-oxide rhombs and aggregates of Fe-oxide grains at the interface between the basalts and amorphous silicate crusts exhibited evidence of microbial colonization. Many of these were Cu-bearing Fe-oxides that were associated with microbial material, and we also detected taxa involved in iron metabolism and/or promotion of copper mobilization. Our combined results suggest that the Cu-enriched Fe-oxides we detected may have resulted from localized Fe oxidation and mobilization of Cu by the microbial communities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sauro, F.; Pozzobon, R.; Massironi, M.; De Berardinis, P.; Santagata, T.; De Waele, J. Lava tubes on Earth, Moon, and Mars: A review on their size and morphology revealed by comparative planetology. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 209, 103288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.W.; Holcomb, R.T.; Tilling, R.I.; Christiansen, R.L. Development of lava tubes in the light of observations at Mauna Ulu, Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii. Bull. Volcanol. 1994, 56, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, P. Genetic processes of cave minerals in volcanic environments: An overview. J. Cave Karst Stud. 2005, 67, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sawlowicz, Z. A short review of pyroproducts (lava tubes). Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 2020, 90, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, D.M.; McAdam, A.C.; Yang, C.S.-C.; Millan, M.; Arevalo, R.; Achilles, C.N.; Knudson, C.; Hewagama, T.; Nixon, C.A.; Fishman, C.; et al. Spectroscopic comparisons of two different terrestrial basaltic environments: Exploring the correlation between nitrogen compounds and biomolecular signatures. Icarus 2023, 402, 115626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.B. Secondary minerals in volcanic caves: Data from Hawai’i. J. Cave Karst Stud. 2009, 72, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, S.J.; van Ruitenbeek, F.J.A.; Foing, B.H.; Sanchez-Roman, M. Multitechnique characterization of secondary minerals near HI-SEAS, Hawaii, as martian subsurface analogues. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Pimentel, J.L.; Martin-Pozas, T.; Jurado, V.; Miller, A.Z.; Caldeira, A.T.; Fernandez-Lorenzo, O.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Prokaryoyic communities from a lava tube in La Palma Island (Spain) are involved in the biogeochemical cycle of major elements. Peer J. 2021, 9, e11386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byloos, B.; Maan, h.; Van Houdt, R.; Boon, N.; Leys, N. The ability of basalt to leach nutrients and support growth of Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 depends on basalt composition and element release. Geomicrobiol. J. 2018, 35, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podia, M.; Yadav, P.; Hooda, S.; Diwan, P.; Gupta, R.K. Microbial weathering of rocks in natural habitat: Genetic basis and omics-based exploration. In Weathering and Erosion Processes in the Natural Environment; Singh, V.B., Madhav, S., Pant, N.C., Shekhar, R., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 265–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kopacz, N.; Csuka, J.; Baque, M.; Iakubivskyi, I.; Guolaugardottir, H.; Klarenberg, I.J.; Ahmed, M.; Zetterlind, A.; Singh, A.; Loes ten Kate, I.; et al. A study in blue: Secondary copper-ric minerals and their associated bacterial diversity in Icelandic lava tubes. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2022EA002234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Huang, L.; Zhao, L.-J.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, X.; Sheng, Y.; Shi, L.; Wu, G.; Jiang, H.; Li, F.; et al. A critical review of mineral-microbe interaction and co-evolution: Mechanisms and applications. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwac128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopker, S.N.; Breitenbach, S.F.M.; Grainger, M.; Stirling, C.H.; Hartland, A. Characterising the decay of organic metal complexes in speleothem-forming cave waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2024, 373, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Gonzalez-Pimentel, J.L.; Jiminez-Morillo, N.T.; Sauro, F.; Guitierrez-Patricio, S.; De la Rosa, J.M.; Tomasi, I.; Massironi, M.; Onac, B.P.; Tiago, I.; et al. Connecting molecular biomarkers, mineralogical composition, and microbial diversity from Mars analog lava tubes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, T.; Bryce, C.; Landenmark, H.; Marie-Loudon, C.; Nicholson, N.; Stevens, A.H.; Cockell, C. Microbial weathering of minerals and rocks in natural environments. In Biogeochemical Cycles—Ecological Drivers and Environmental Impact; Dontsova, K., Balogh-Brunstad, Z., Le Roux, G., Eds.; Wiley-AGU: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 251, pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, C.B.; Bevilacqua, J.G.; Hahn, A.S.; Morgan-Lang, C.; Wagner, N.; Gadson, O.; McAdam, A.C.; Bleacher, J.E.; Achilles, C.N.; Knudson, C.; et al. Extreme niche partitioning and microbial dark matter in a Mauna Loa lava tube. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2023, 128, e2022JE007283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrup, D.E.; Melim, L.A.; Spilde, M.N.; Hathaway, J.J.M.; Garcia, M.G.; Moya, M.; Stone, F.D.; Boston, P.J.; Dapkevicius, M.L.N.E.; Riquelme, C. Lava and cave microbial communities withn mats and secondary mineral deposits: Implications for life detection on other planets. Astrobiology 2011, 11, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itcus, C.; Pascu, M.D.; Lavin, P.; Persoiu, A.; Iancu, L.; Purcarea, C. Bacterial and acrchaeal community structures in perennial ice cave. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, K.H.; Winter, A.S.; Read, K.J.H.; Hughes, E.M.; Spilde, M.N.; Northup, D.E. Comparison of bacterial communities from lava cave microbial mats to overlying surface soilds from Lava Beds National Monument, USA. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, R.D.; Zamkovaya, T.; Donachie, S.P.; Northrup, D.E.; Medley, J.J.; Monsalve, N.; Saw, J.H.; Decho, A.W.; Chain, P.S.G.; Boston, P.J. Islands within islands: Bacterial phylogenetic structure and consortia in Hawaiian lava caves and fumaroles. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 934708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk-Zak, K.; Zielenkiewicz, U. Microbial diversity in caves. Geomicrobiol. J. 2016, 33, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, M.G.; Hathaway, J.J.M.; Northrup, D.E.; Spilde, M.N.; Moser, D.P.; Blank, J.G. Bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic life of volcanic cave features from Lava Beds National Monument, California, USA. Geomicrobiol. J. 2025, 42, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze-Lam, S.; Fortin, D.; Davis, B.S.; Beveridge, T.J. Mineralization of bacterial surfaces. Chem. Geol. 1996, 132, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.; Dove, P.M. An overview of biomineralization processes and the problem of the vital effect. In Biomineralization; Dove, P.M., De Yoreo, J.J., Weiner, S., Rosso, J.J., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M.; Hinman, N.W.; Potter-McIntyre, S.L.; Schubert, K.E.; Gillams, R.J.; Awramik, S.M.; Boston, P.J.; Bower, D.M.; Des Marais, D.J.; Farmer, J.D.; et al. Deciphering biosignatures in planetary contexts. Astrobiology 2019, 19, 1075–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boston, P.J.; Spilde, M.N.; Northup, D.E.; Melim, L.A.; Soroka, D.S.; Kleina, L.G.; Lavoie, K.H.; Hose, L.D.; Mallory, L.M.; Dahm, C.N.; et al. Cave biosignature suites: Microbes, minerals, Mars. Astrobiology 2001, 1, 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, D.M.; Hummer, D.R.; Steele, A.; Kyono, A. The co-evolution of Fe,-Ti,-oxides and other microbially induced mineral precipitates in sandy sediments: Understanding the role of cyanobacteria in weathering and early diagenesis. J. Sediment. Res. 2015, 85, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfan, G.A.; McKeown, D.A.; Post, J.E. Mineralogical characterization of biosilicas versus geological analogs. Geobiology 2023, 21, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzerara, K.; Bernard, S.; Miot, J. Mineralogical identification of traces of life. In Biosignatures for Astrobiology; Cavalazzi, B., Westall, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Lin, W. A suite of spectroscopic devices as a potential tool to discriminate biotic and abiotic materials with igneous rock. Icarus 2024, 407, 115804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, M.; Hays, L.E.; Voytek, M.A.; New, M.H.; Schulte, M.D. The ladder of life detection. Astrobiology 2018, 18, 1375–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, D.M.; Yang, C.S.-C.; Hewagama, T.; Nixon, C.A.; Aslam, S.; Whelley, P.L.; Eigenbrode, J.L.; Jin, F.; Ruliffson, J.; Kolasinski, J.R.; et al. Spectroscopic characterization of samples from different environments in a volcano-glacial region in Iceland: Implications for in situ planetary exploration. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2021, 263, 120205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, I.-M.; Wang, A. Application of laser Raman micro-analyses to Earth and planetary materials. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 145, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehlicka, J.; Edwards, H.G.M. Raman spectroscopy as a tool for the non-destructive identification of organic minerals in the geologic record. Org. Geochem. 2008, 39, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, I.; Jorge-Villar, S.E.; van Wesemael, B.; Lazaro, R. Raman spectroscopy detection of biomolecules in biocrusts from differening environmental conditions. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 171, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Jolliff, B.L.; Haskin, L.A. Raman spectroscopic characterization of a highly weathered basalt: Igneous mineralogy, alteration products, and a microorganism. J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 27067–27077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, H.G.M.; Hutchinson, I.B.; Ingley, R.; Jehlicka, J. Biomarkers and their Raman spectroscopic signatures: A spectral challenge for analytical astrobiology. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2014, 372, 20140193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasteris, J.D.; Beyssac, O. Welcome to Raman spectroscopy: Successes, challenges, and pitfalls. Elements 2020, 16, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, Z.; Makreski, P.; Gajic, B. Identification and spectra-structure determination of soil minerals: Raman study supported by IR spectroscopy and X-ray powder diffraction. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2010, 41, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.S.-C.; Bower, D.M.; Jin, F.; Hewagama, T.; Aslam, S.; Nixon, C.A.; Kolasinski, J.; Samuels, A.C. Raman and UVN+LWIR LIBS detection system for in situ surface chemical identification. Methods X 2022, 9, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malherbe, C.; Hutchinson, I.B.; Ingley, R.; Boom, A.; Carr, A.S.; Edwards, H.; Vertruyen, B.; Gilbert, B.; Eppe, G. On the habitability of desert varnish: A combined study by micro-Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and methylated pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Astrobiology 2017, 17, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, M.; Campbell, K.A.; Sriaporn, C.; Handley, K.M.; Teece, B.L.; Mahaffy, P.; Johnson, S.S. Recovery of lipid biomarkers in hot spring digitate silica sinter as analogs for potential biosignatures on Mars: Results from laboratory and flight-like expleriments. Astrobiology 2025, 25, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.; Tu, V.; Bristow, T.; Rampe, E.; Vaniman, D.; Chipera, S.; Sarrazin, P.; Morris, R.; Morrison, S.; Yen, A.; et al. The chemistry and mineralogy (CheMin) X-ray diffractometer on the MSL Curiosity rover: A decade of mineralogy from Gale carte, Mars. Minerals 2024, 14, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhartia, R.; Beegle, L.W.; DeFlores, L.; Abbey, W.; Razzell Hollis, J.; Uckert, K.; Monacelli, B.; Edgett, K.S.; Kennedy, M.R.; Sylvia, M.; et al. Perserverance’s Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals (SHERLOC) Investigation. Space Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffy, P.; Webster, C.R.; Cabane, M.; Conrad, P.G.; Coll, P.; Atreya, S.K.; Arvey, R.; Barciniak, M.; Benna, M.; Bleacher, L.; et al. The Sample Analysis at Mars investigation and instrument suite. Space Sci. Rev. 2012, 170, 401–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Rull Perez, F. The SuperCam remote sensing instrument suite for the Mars 2020 rover: A preview. Spectroscopy 2017, 32, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Crown, D.A.; Scheidt, S.P.; Berman, D.C. Distribution and morphology of lava tube systems on the Western flank of Alba Mons, Mars. JGR Planets 2022, 127, e2022JE007263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveille, R.J.; Datta, S. Lava tubes and basaltic caves as astrobiological targets on Earth and Mars: A review. Planet. Space Sci. 2010, 58, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, D.C.; Grove, T.L. Petrology of Medicine Lake highland volcanics: Characterization of endmembers of magma mixing. Contrib Miner. Pet. 1982, 80, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlmann, B.L.; Edwards, C.S. Mineralogy of the martian surface. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2014, 42, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.S.-C.; Jin, F.; Trivedi, S.B.; Brown, E.; Hommerich, U.; Tripathi, A.B.; Samuels, A.C. Long-Wave Infrared (LWIR) Molecular Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) Emissions of Thin Solid Explosive Powder Films Deposited on Aluminum Substrates. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017, 71, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, V.M.; Chen, I.-M.A.; Palaniappan, K.; Chu, K.; Szeto, E.; Grechkin, Y.; Ratner, A.; Jacob, B.; Huang, J.; Williams, P.; et al. IMG: The integrated microbial genomes database and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. A geochemical study of speleothems and cave waters in basaltic caves at Lava Beds National Monument, Northern California, USA. Master’s Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, H.V.; Ford, J.; Blank, J.G.; Park, M.; Datta, S. Geochemical interations among water, minerals, microbes, and organic matter in formation of speleothems in volcanic (lava tube) caves. Chem. Geol. 2022, 594, 120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, A.G.; Thomas, P.S.; Ray, A.S. Characterisation of sedimentary opals by Fourier transform Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 1997, 53, 2341–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, P.; Piriou, B.; Navrotsky, A. A Raman spectroscopic study of glasses along the joins silica-calcium aluminate, silica-sodium aluminate, and silica-potassium aluminate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1982, 46, 2021–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.G.; Reyes, B.A.; Fritsch, E.; Faulques, E. Vibrational states in opals revisited. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 11968–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, N.J.; Gasscooke, J.R.; Johnston, M.R.; Pring, A. A review of classification of opal with reference to recent new localities. Minerals 2019, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, A.; Mihailova, B.; Tsintsov, Z.; Petrov, O. Structural state of microscrystalline opals: A Raman spectroscopic study. Am. Mineral. 2007, 92, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moros, J.; Laserna, J.J. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) of organic compounds: A review. Appl. Spectrosc. 2019, 73, 963–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloprogge, J.T. Raman spectroscopy of clay minerals. In Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies of Clay Minerals; Gates, W., Kloprogge, J.T., Madejova, J., Bergaya, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 150–199. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.J. Weathering of the primary rock-forming minerals: Processes, products and rates. Clay Miner. 2004, 39, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, Y.; Colin, F.; Nahon, D.; Delvigne, J.; Michaux, L. Secondary-mineral formation during natural weathering of pyroxene: Review and thermodynamic approach. Am. J. Sci. 1993, 293, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Martinez, R.; Barragan, R.; Geraldi-Campesi, H.; Lanczos, T.; Vidal-Romani, J.R.; Aubrecht, R.; Bernal Uruchurtu, J.P.; Puig, T.P.; Espinasa-Perena, R. Morphological and mineralogical characterization of speleothems from the Chimalacatepec lava tube system, Central Mexico. Int. J. Speleol. 2016, 45, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleton, R.A.; Foudoulis, C.; Varkevisser, D. Weathering of basalt: Changes in rock chemistry and mineralogy. Clays Clay Miner. 1987, 35, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G.M. Metals, minerals and microbes: Geomicrobiology and bioremediation. Microbiology 2010, 156, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.A.; Bennet, P.C. Mineral microniches control the diversity of subsurface microbial populations. Geomicrobiol. J. 2014, 31, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Patricio, S.; Osman, J.R.; Gonzalez-Pimentel, J.L.; Jurado, V.; Laiz, L.; Lainez Concepcion, A.; Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Miller, A.Z. Microbiological exploration of Cueva del Viento lava tube system in Tenerife, Canary Islands. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 16, e13245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall Hathaway, J.J.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; De Lurdes, N.E.; Dapkevicius, M.; Northup, D.E. Diversity of ammonia oxidation (amoA) and nitrogen fixation (nifH) genes in lava caves of Terceira, Azores, Portugal. Geomicrobiol. J. 2014, 31, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiori, C.; John, Z.; Bower, D.M.; Millan, M.; Hahn, A.S.; McAdam, A.; Johnson, S.S. Draft genome sequence of a member of a putatively novel Rubrobacteraceae genus from lava tubes in Lava Beds National Monument. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2025, 14, e0133524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Driessche, A.E.S.; Stawski, T.M.; Kellermeier, M. Calcium sulfate precipitation pathways in natural and engineered environments. Chem. Geol. 2019, 530, 119274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Taboada, N.; Gomez-Laserna, O.; Martinez-Arkarazo, I.; Olazabal, M.A.; Madariaga, J.M. Raman spectra of the different phases in the CaSO4-H2O system. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10131–10137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-S.C.; Jin, F.; Trivedi, S.; Hommerich, U.; Nemes, L.; Samuels, A.C. Long wave infrared laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy of complex gas molecules in the vicinity of a laser-induced plasma. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 294, 122536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapados, C.; Lemieux, S.; Carpentier, R. Protein and chlorophyll in photosystem II probed by infrared spectroscopy. Biophys. Chem. 1991, 39, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpugov, E.L.; Degtyareva, O.V.; Savransky, V.V. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis of Pigments in Fresh Tobacco Leaves. Phys. Wave Phenom. 2019, 27, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmann, R.P.; Kniseley, R.N.; Fassel, V.A. The infrared spectra of isocyanates. Spectrochim. Acta 1965, 21, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiuppa, A.; Allard, P.; D’Alessandro, W.; Michel, A.; Parello, F.; Treuil, M.; Valenza, M. Mobility and fluxes of major, minor and trace metals during basalt weathering and groundwater transport at Mt. Etna volcano (Sicily). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2000, 64, 1827–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, H.; Myronova, N.; Boden, R. Microbial degradation of dimethylsulphide and related C1-sulphur compounds: Organisms and pathways controlling fluxes of sulfur in the biosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, G.; Gonzalez-Pimentel, J.L.; Piano, E.; Isaia, M.; Miller, A.Z. First insights into the bacterial diversity of Mount Etna volcanic caves. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 1632–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, R.; Vergara-Barros, P.; Alcorta, J.; Alcaman-Arias, M.E.; Levican, G.; Ridley, C. Distribution and Activity of Sulfur-Metabolizing Bacteria along the Temperature Gradient in Phototrophic Mats of the Chilean Hot Spring Porcelana. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cron, B.; Macalady, J.L.; Cosmidis, J. Organic stabilization of extracellular elemetal sulfur in a sulfurovun-rich biofilm: A new role for extracellular polymeric substances? Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 720101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Dahl, C. A novel bacterial sulfur oxidation pathway provides a new link between the cycles of organic and inorganic sulfur compounds. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2479–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristiansen, A.; Lindholst, S.; Feilberg, A.; Nielsen, P.H.; Neufeld, J.D.; Nielsen, J.L. Butryic acid- and dimethyly disulfide-assimilating microorganisms in a biofilter treating air emissions from a livestock facility. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8595–8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabizadeh, T.; Peacock, C.L.; Benning, L.G. Carboxylic acids: Effective inhibitors for calcium sulfate precipitation? Mineral. Mag. 2014, 78, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.D. NIST Chemistry WebBook. In NIST Standard Reference Database; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne, W.J.B.; Rufledt, C.J.; Marshall, C.P. Raman spectroscopy of the eight natural carbonate minerals of calcite structure. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2018, 49, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacksberg, J.; Rossman, G.R.; Gleckler, A. Time-resolved Raman spectroscopy for in situ planetary mineralogy. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, 4951–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanesch, M. Raman spectroscopy of iron oxides and (oxy)hydroxides at low laser power and possible applications in environmental magnetic studies. Geophys. J. Int. 2009, 177, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larese-Casanova, P.; Haderlein, S.B.; Kappler, A. Biomineralization of lepidocrocite and geothite by nitrate-reducing Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria: Effects of pH, bicarbonate, phosphate, and humic acids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 3721–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralchenko, Y.; Jou, F.-C.; Kelleher, D.E.; Kramida, A.E.; Musgrove, A.; Reader, J.; Wiese, W.L.; Olson, K. NIST Atomic Spectra Database; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yogi, A.; Varshney, D. Cu doping effect of hematite (a-Fe2-xCuxO3): Effect on the structural and magnetic properties. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2014, 21, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moppert, X.; Costaouec, T.L.; Raguenes, G.; Courtois, A.; Simon-Colin, C.; Crassous, P.; Costa, B.; Guesennec, J. Investigations into the uptake of copper, iron and selenium by a highly sulphated bacterial exopolysaccharide isolated from microbial mats. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 36, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivleva, N.P.; Wagner, M.; Horn, H.; Niessner, R.; Haisch, C. Towards a nondestructive chemical characterization of biofilm matriz by Raman microscopy. Anal Bioanal Chem 2009, 393, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czamara, K.; Majzner, K.; Pacia, M.Z.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M. Raman spectroscopy of lipids: A review. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2014, 46, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehlicka, J.; Edwards, H.G.M.; Oren, A. Raman spectroscopy of microbial pigments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3286–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Fernandez, J.B.; Aceves Suriano, C.E.; Thalasso, F.; Montoya-Ciriaco, N.; Dendooven, L. Structural and functional bacterial biodiversity in a copper, zinc, and nickel amended bioreactor: Shotgun metagenomic study. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaparthi, D.; Pommerenke, B.; Casper, P.; Dumont, M.G. Chemolithotrophic nitrate-dependent Fe(II)-oxidizing nature of actinobacterial subdivision lineage TM3. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1582–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujan, A.M.; Gomez, P.; Buckling, A. Siderophore cooperation of the bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens in soil. Biol. Lett. 2015, 11, 20140934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farda, B.; D’jebaili, R.; Vaccarelli, I.; Del Gallo, M.; Pellegrini, M. Actinomycetes from caves: And overview of their diversity, biotechnological properties, and insights for their use in soil environments. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Yu, F.; Penttinen, P. Isolation, characterization, and evaluation of a high-siderophore-yielding bacterium from heavy metal–contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 3888–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addadi, L.; Raz, S.; Weiner, S. Taking advantage of disorder: Amorphous calcium carbonate and its roles in biomineralization. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherpin, C.; Lister, D.; Dacquait, F.; Liu, L. Study of the solid-state synthesis of nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4) by x-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Raman spectroscopy. Materials 2021, 14, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, P.R.; Johnston, C.; Campaniello, J.J. Raman scattering in spinel structure ferrites. Mater. Res. Bull. 1988, 23, 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

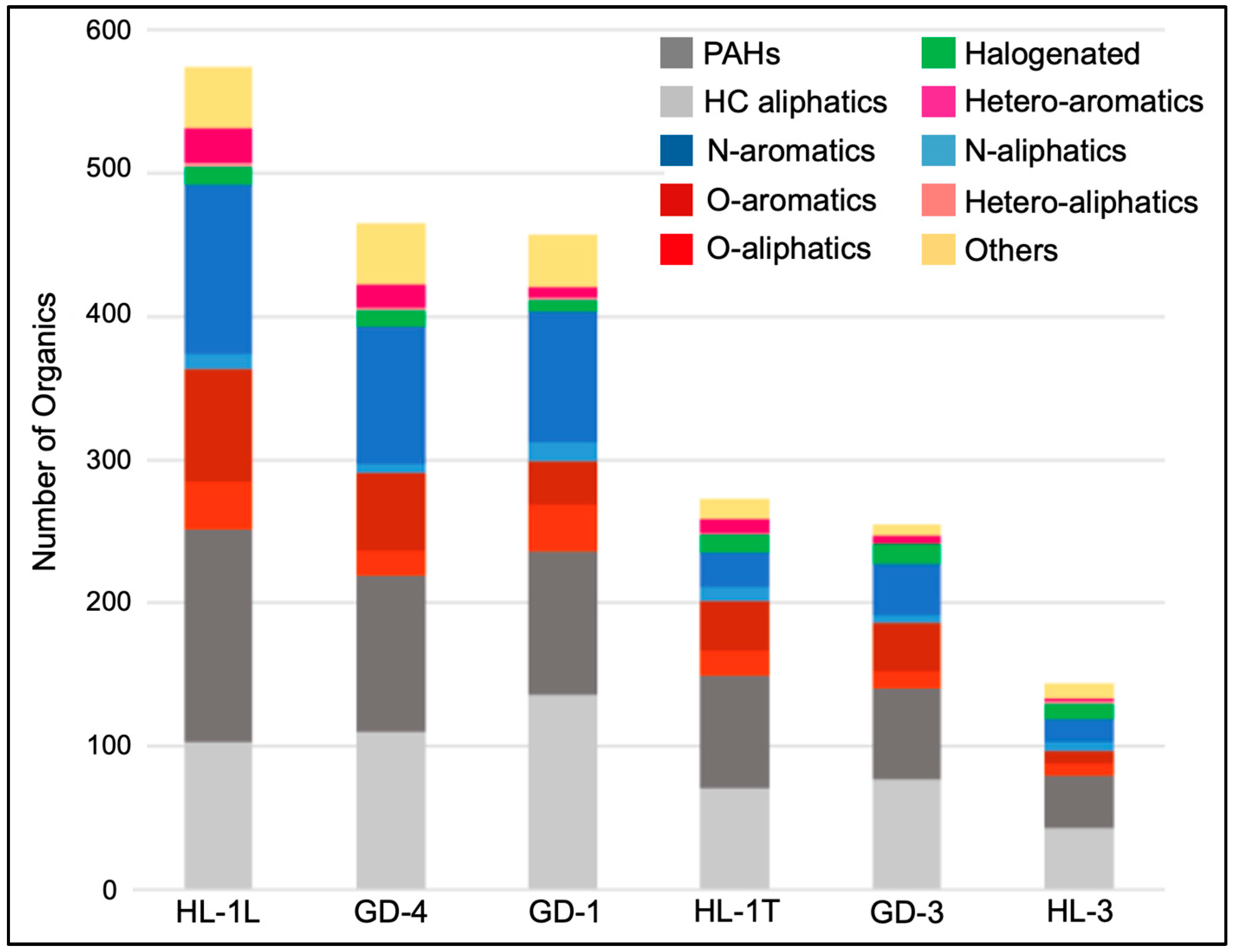

| Sample | Source Area | Mineralogy | Elemental Composition | Organic Compounds | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman & XRD | UV-VIS LIBS | EDS | Raman | LWIR LIBS | ||

| HL-1L | Chamber after 2nd entrance, lower left wall near floor | Amorphous silicates, smectite clays, calcite, plagioclase, Cu-hematite | Major: Ca, Ti, Al, Mg, Si, Na, Cu, V Minor: S, Fe, Mn, Ni, Cr, C2, Ti | Si, Al, Ca, Mg, Na, K, C, N, S, P, Cl, Fe, Ni, Ti | Organic acids, N-compounds | H2O, O-Si-O, SCN CO, CN, COC |

| HL-1T | Chamber after 2nd entrance, upper left wall above HL-1L | Amorphous silicates, smectite clays, calcite, gypsum, orthoclase, pyroxene, hematite, ilmenite, magnetite, Ni-ferrite, Cu-hematite | Major: Ca, Al, Mg, Na, V Minor: S, Si, Fe, Mn, Ni, Ti, Cu | Si, Al, Ca, S, Mg, Fe, C, Na, N, K, Ni, P, Cl, Cu, Ti | Organic acids, carotenoids | H2O, O-Si-O, O-S-O |

| HL-2 | Chamber after 2nd entrance, low ceiling | Amorphous silicates, gypsum, Cu-Fe-oxides, hematite, Ni-Ferrite, pyroxene, anorthite | Major: Ca, Fe, Mg, Si, Na, Cu, V Minor: S, Ti, Al, Mn, Ni, Cr, C2 | Si, Al, Ca, S, Fe, Mg, C, N, Cu, Ti, P, Cl | Organic acids, carotenoids, N-compounds | H2O, O-Si-O, SCN CO, CH, CN, COC |

| HL-3 | Distant Light; 1st entrance, around a wet opening | Amorphous silicates, smectite/vermiculite clays, Fe-oxides, anorthoclase | Major: Al, Fe, Ti, Mg, Si, Na, Cu, V, Ni, Cr Minor: S, Ca, C2 | Si, Al, Ca, Fe, Mg, C, N, Ni, Zn, Ti, K, Na | Organic acids | H2O, O-Si-O, OCN, SCN CN, COC |

| GD1 | Chamber 1, ceiling + wall | Amorphous silicates, smectite clays, calcite, anorthoclase, pyroxene, hematite | Major: Ca, Fe, Ti, Mg, Si, Al, Na, Cu, Li Minor: S, Cr, V, H | Si, Al, Mg, Ca, S, C, Na, Fe, K, N | Organic acids | O-Si-O, CN, COC H2O, O-S-O |

| GD-2 | Chamber 1, wall, small ledge | Amorph silicates, Na-plagioclase, pyroxene, calcite, FeCu-oxide | Major: Mg, Si, Na, Ca, Cu Minor: S, Fe, Cr, C2, V, Li, Al, Ti | Si, Al, Mg, Fe, Ca, C, N, P, Na, K, Cu, Cr | Organic acids | H2O, O-Si-O, SCN CO, CN |

| GD-3 | Chamber 1, ceiling + wall | Amorph Si, quartz, anorthoclase, Fe-oxide | Major: Ca, Mg, Si, Al, Na, Cu, Li Minor: S, Fe, Al, Cr, C2, V, Ti | Si, Al, Mg, Ca, C, S, Fe, N, Cu, K, Na, P, Cl, Cr, Ag | Carotenoids, N-compounds, organic acids | H2O, O-Si-O, SCN, CO, CN |

| GD-4 | Chamber 1, opposite wall: low ceiling/wall | Amorph silicates, smectite clays, anorthoclase, Fe-oxides, calcite, clinopyroxene | Major: Ca, Mg, Si, Al, Na, Cu Minor: S, Fe, Li, Cr, V, Ti | Si, Al, Ca, Mg, Fe, Na, S, C, K, Ti, Cl, P | Organic acids | O-Si-O, CO, CN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bower, D.M.; McAdam, A.C.; Yang, C.S.C.; Jin, F.; Millan, M.; Christiann, C.; Mussetta, M.; Knudson, C.; Jarvis, J.; Johnson, S.; et al. Minerals as Windows into Habitability on Lava Tube Basalts: A Biogeochemical Study at Lava Beds National Monument, CA. Minerals 2025, 15, 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121303

Bower DM, McAdam AC, Yang CSC, Jin F, Millan M, Christiann C, Mussetta M, Knudson C, Jarvis J, Johnson S, et al. Minerals as Windows into Habitability on Lava Tube Basalts: A Biogeochemical Study at Lava Beds National Monument, CA. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121303

Chicago/Turabian StyleBower, Dina M., Amy C. McAdam, Clayton S. C. Yang, Feng Jin, Maeva Millan, Clara Christiann, Mathilde Mussetta, Christine Knudson, Jamielyn Jarvis, Sarah Johnson, and et al. 2025. "Minerals as Windows into Habitability on Lava Tube Basalts: A Biogeochemical Study at Lava Beds National Monument, CA" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121303

APA StyleBower, D. M., McAdam, A. C., Yang, C. S. C., Jin, F., Millan, M., Christiann, C., Mussetta, M., Knudson, C., Jarvis, J., Johnson, S., John, Z., Maggiori, C., Whelley, P., & Richardson, J. (2025). Minerals as Windows into Habitability on Lava Tube Basalts: A Biogeochemical Study at Lava Beds National Monument, CA. Minerals, 15(12), 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121303