Constraints on the Origin of Sulfur-Related Ore Deposits in NW Tarim Basin, China: Integration of Petrology and C-O-Sr-S Isotopic Geochemistry

Abstract

1. Introduction

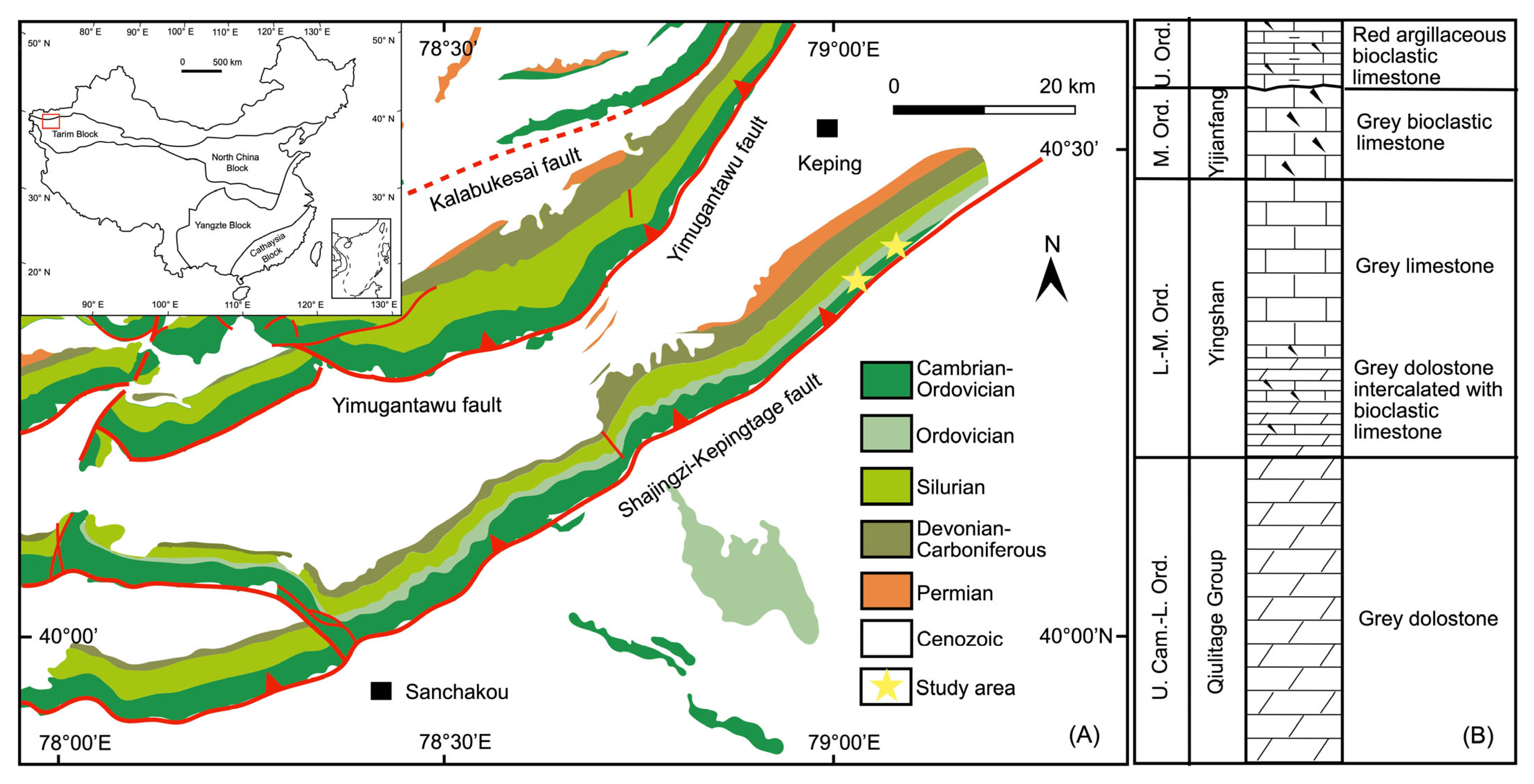

2. Geological Setting

3. Analytical Methods

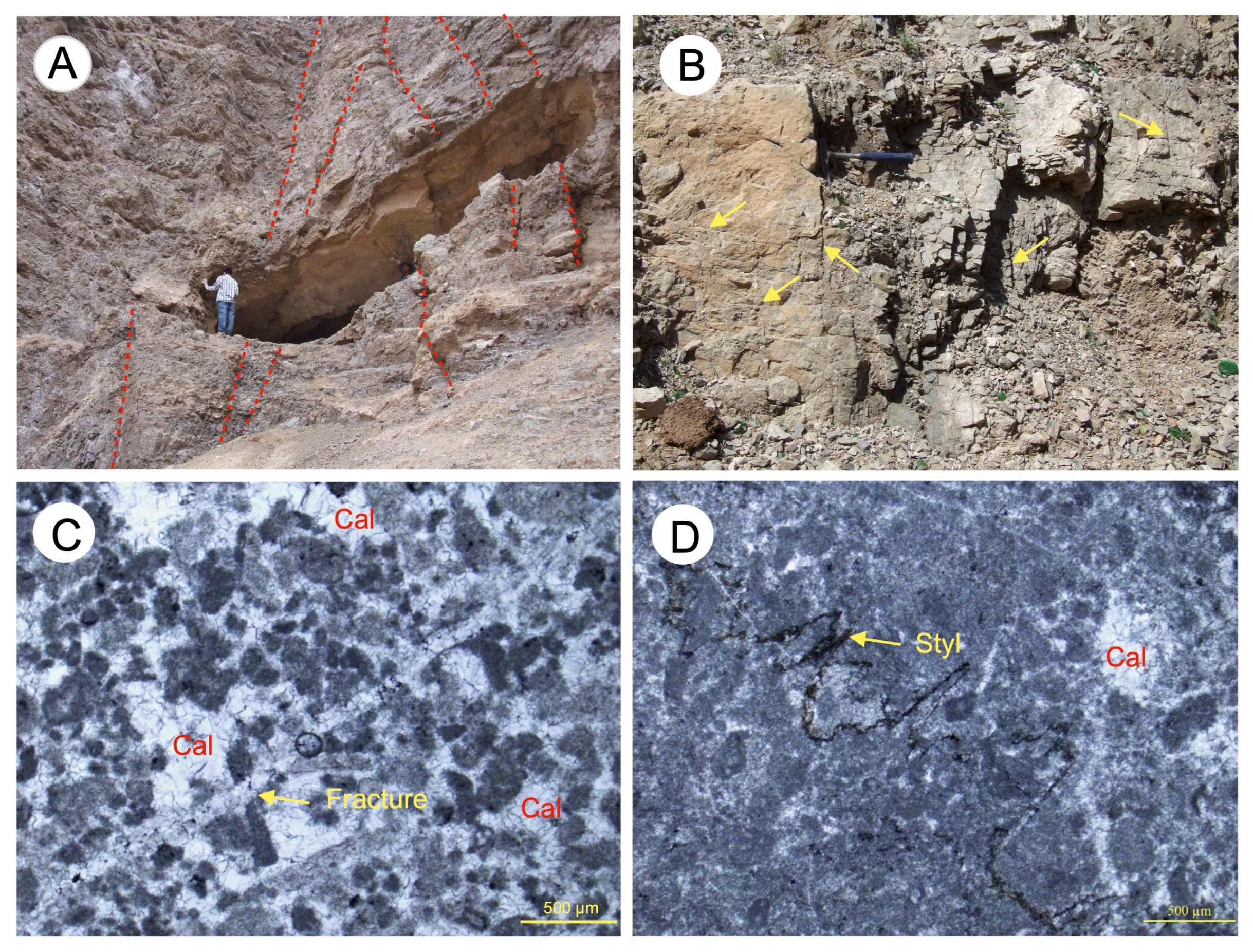

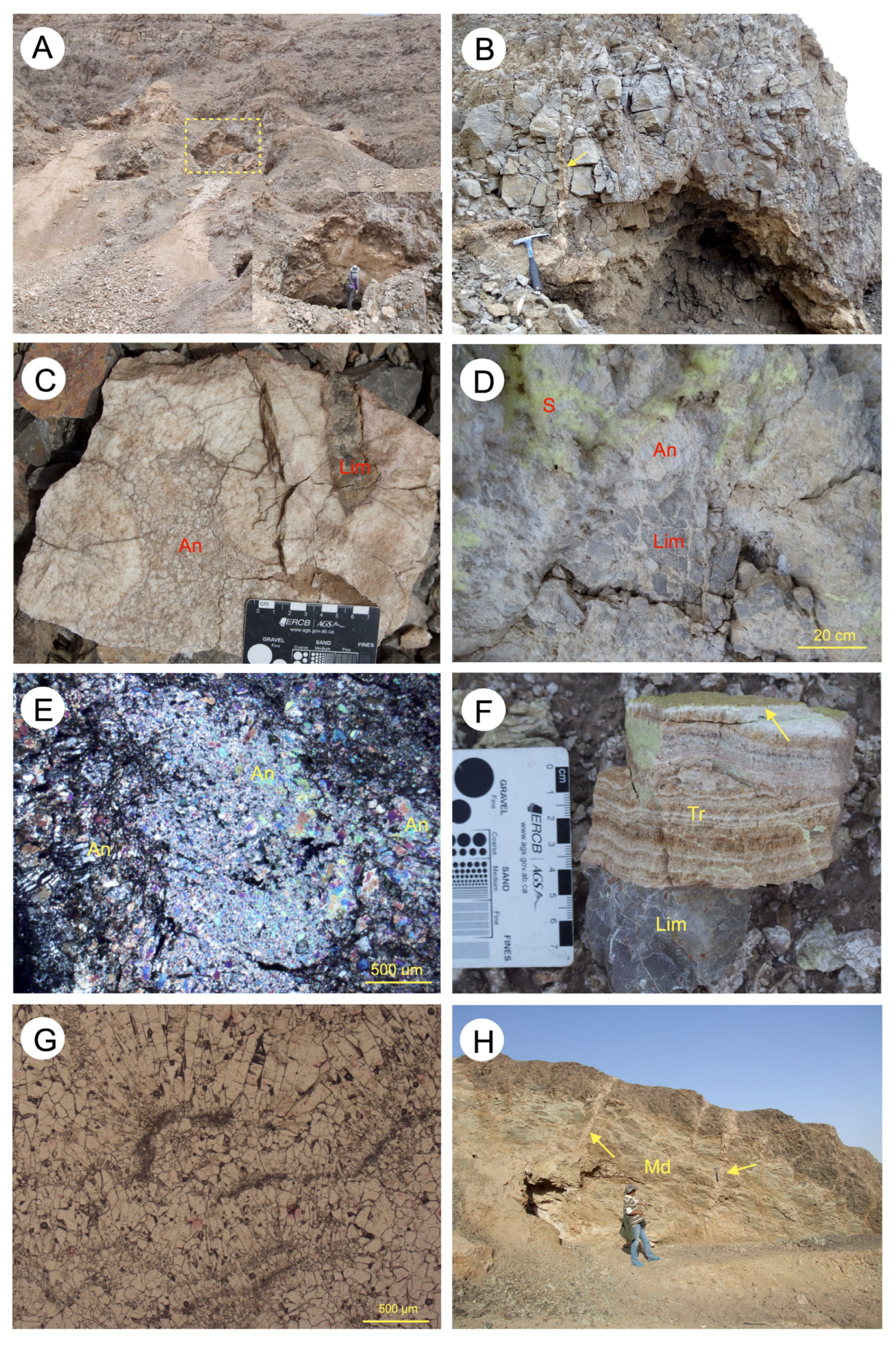

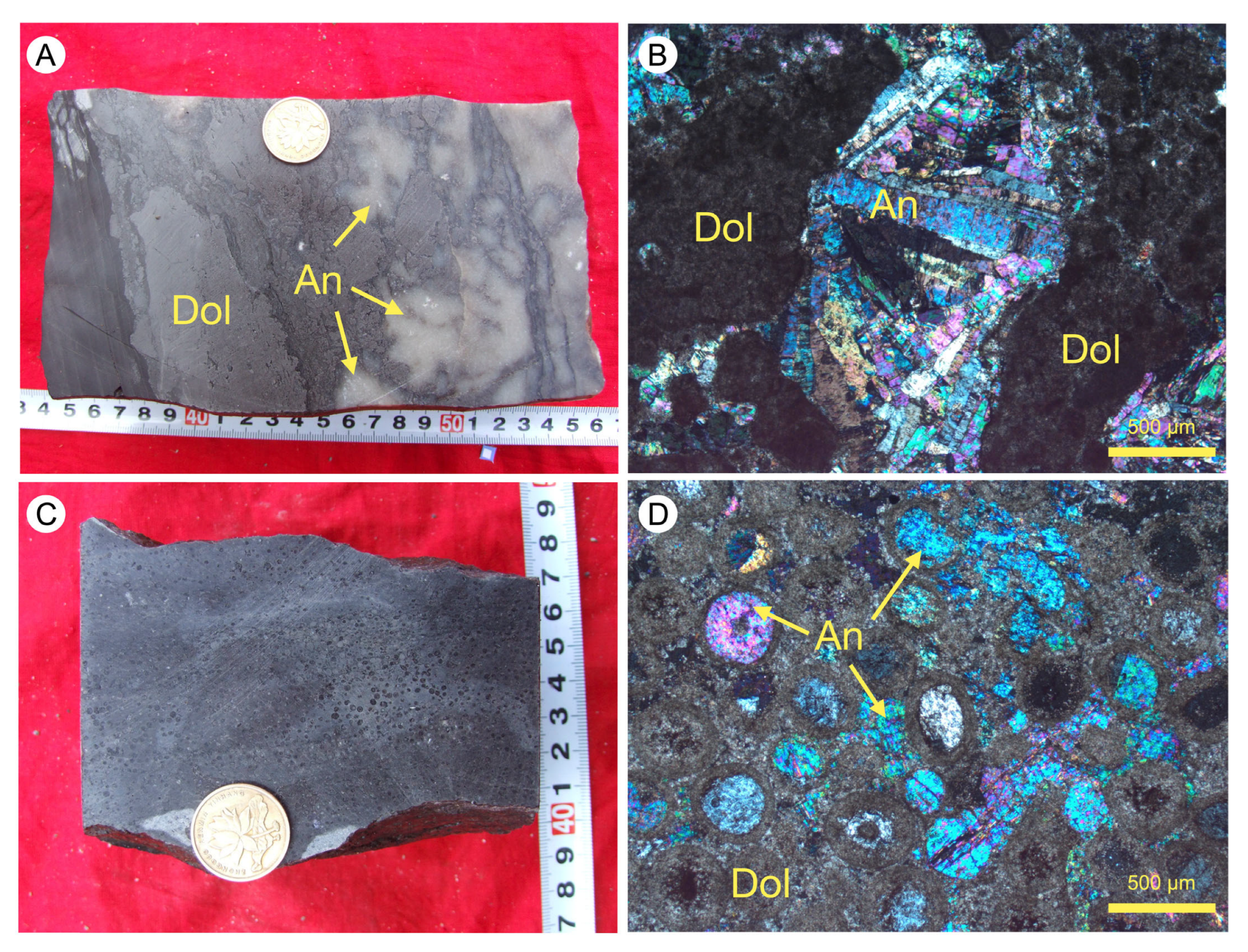

4. Petrology of Sulfur-Related Minerals

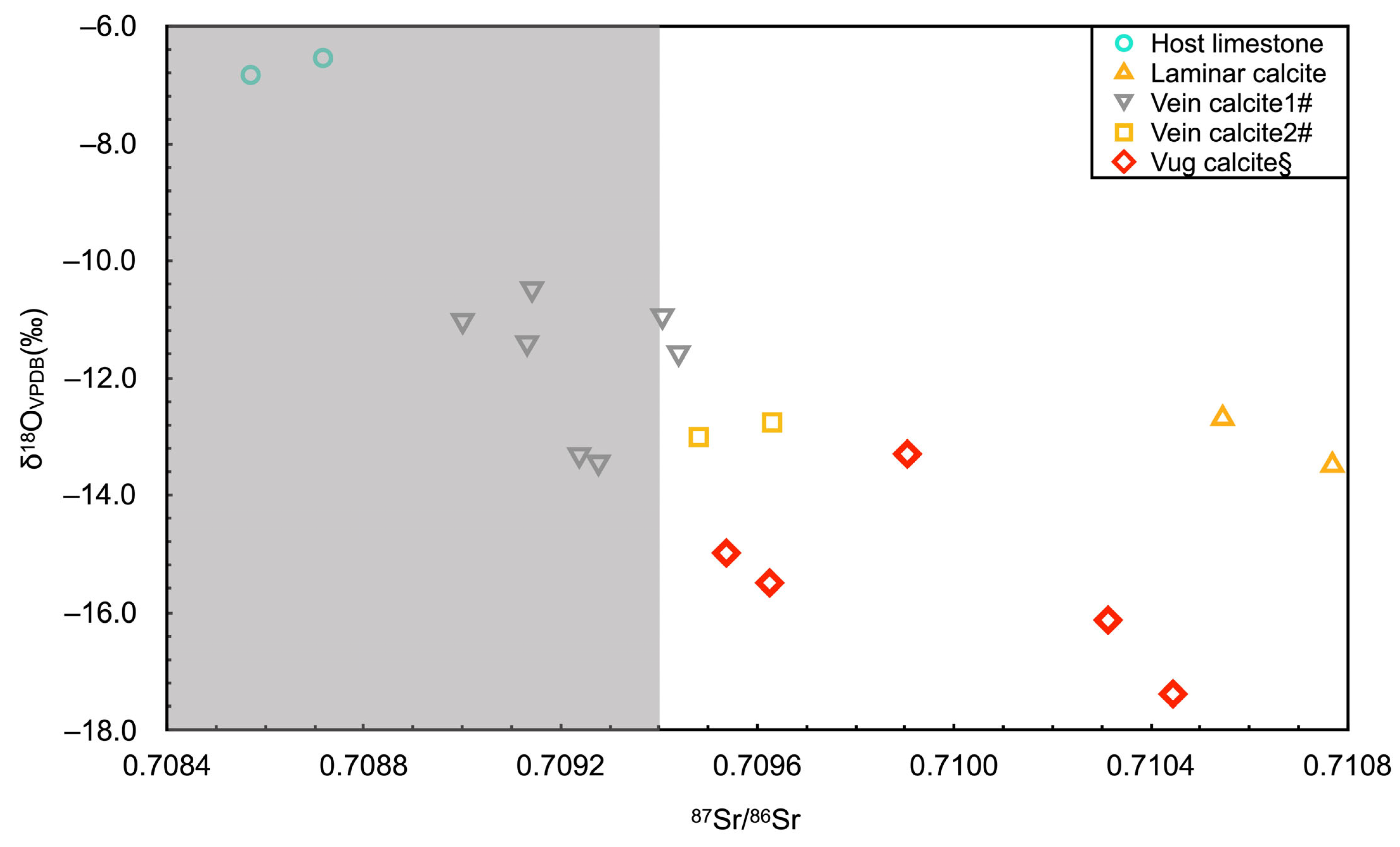

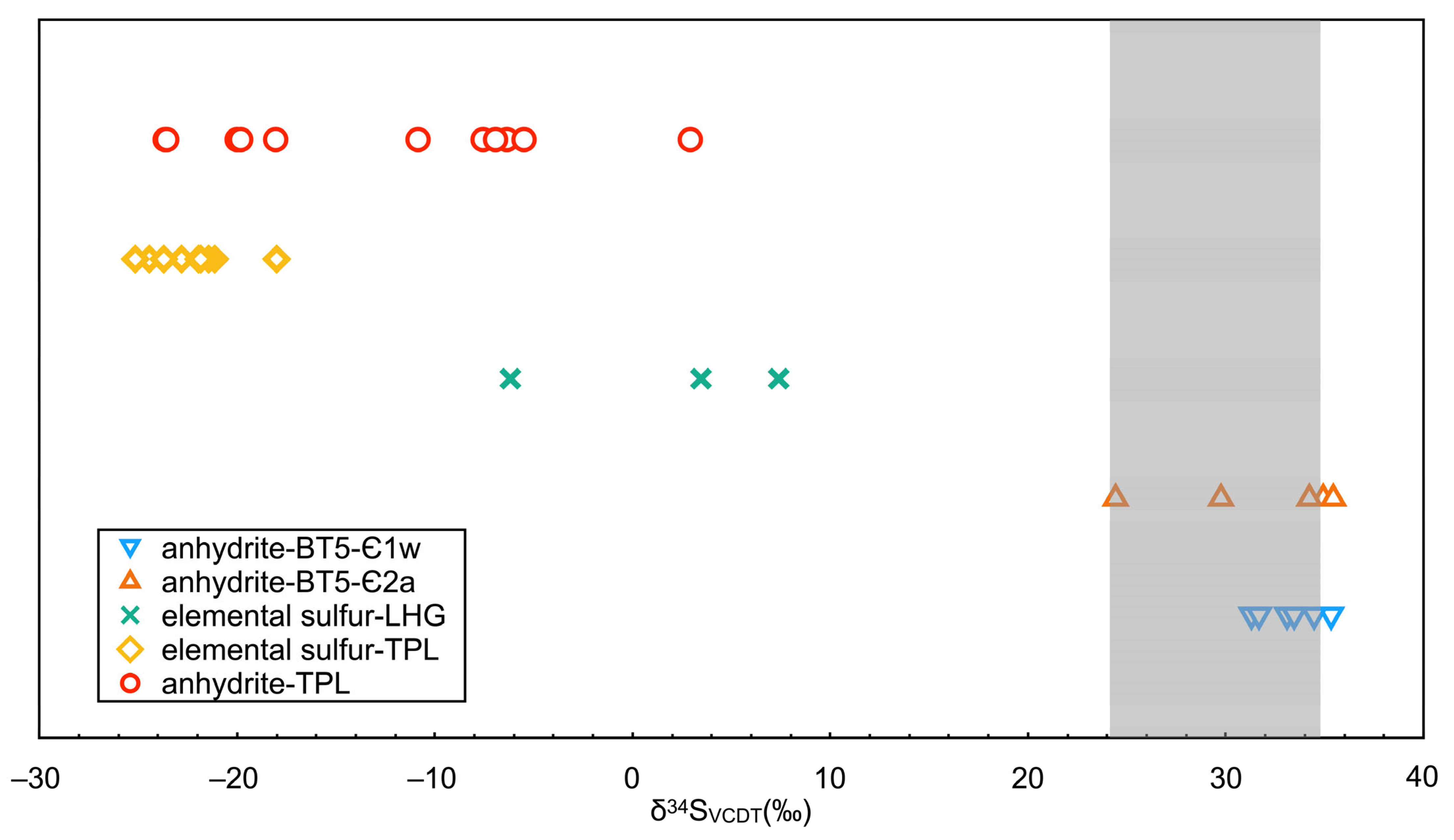

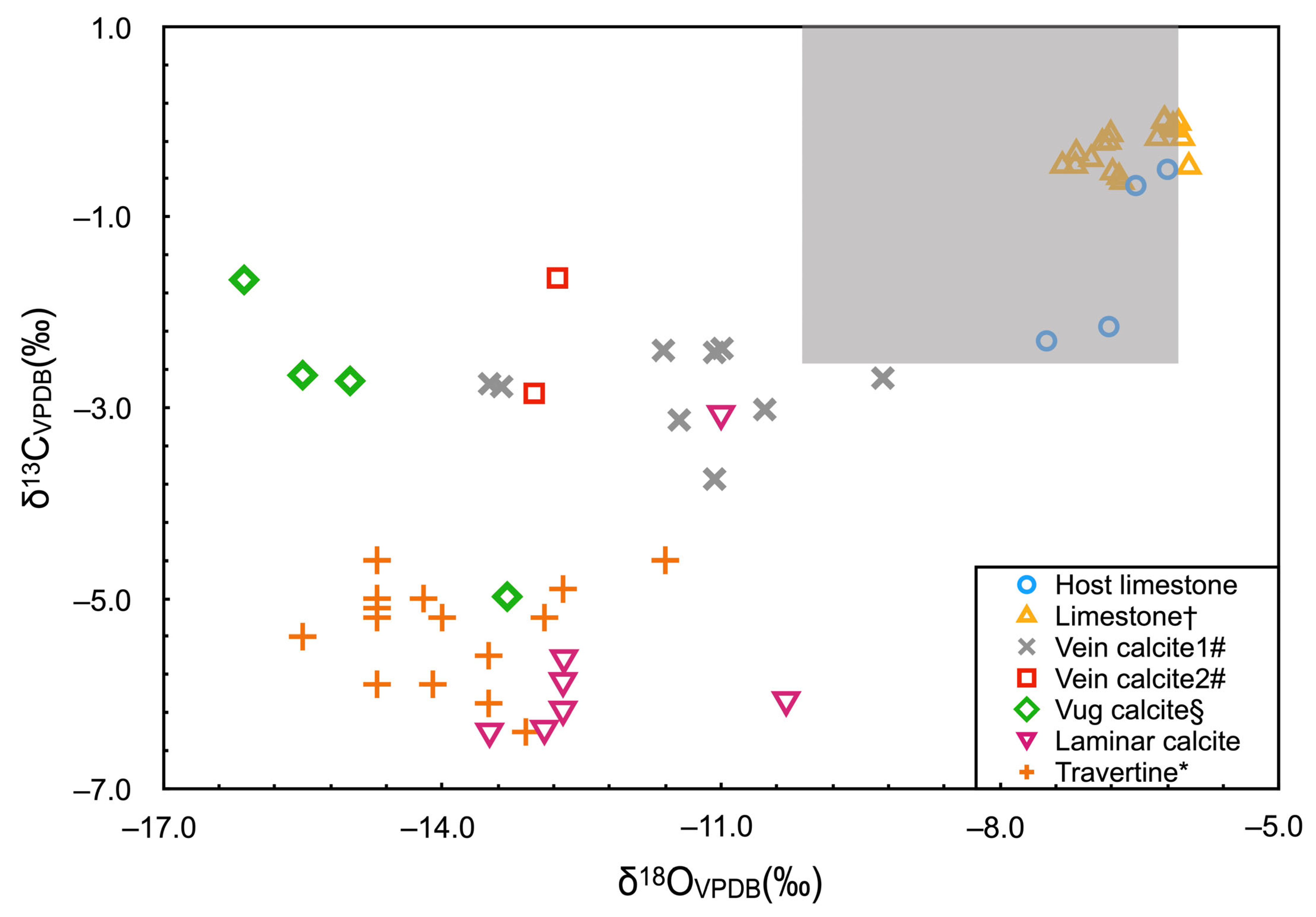

5. Isotopic Geochemistry

| Sample No. | Lithology | δ34SVCDT (‰) | Error (2σ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14TPL-06A | anhydrite | −20.00 | 0.016 |

| 14TPL-09A | anhydrite | −19.82 | 0.025 |

| 14TPL-04B | anhydrite | −18.05 | 0.029 |

| 14TPL-09B | anhydrite | −6.36 | 0.035 |

| 14TPL-10B | anhydrite | −5.49 | 0.058 |

| T081223-1 ** | anhydrite | −10.85 | — |

| T081223-2 ** | anhydrite | −7.56 | — |

| TP25-3 ** | anhydrite | +2.92 | — |

| TP26-1 ** | anhydrite | −6.93 | — |

| TP26-2 ** | anhydrite | −23.64 | — |

| TP26-3 ** | anhydrite | −23.56 | — |

| 14TPL-01A | elemental sulfur | −21.13 | 0.015 |

| 14TPL-02A | elemental sulfur | −24.44 | 0.008 |

| 14TPL-04A | elemental sulfur | −22.81 | 0.018 |

| 14TPL-05A | elemental sulfur | −25.15 | 0.031 |

| 14TPL-08A | elemental sulfur | −18.00 | 0.013 |

| 14PTL-01B | elemental sulfur | −21.44 | 0.016 |

| 14PTL-04B | elemental sulfur | −23.71 | 0.011 |

| 14PTL-05B | elemental sulfur | −21.95 | 0.022 |

| 14PTL-06B | elemental sulfur | −21.84 | 0.012 |

| 14LHG-01A | elemental sulfur | +3.46 | 0.012 |

| 14LHG-03A | elemental sulfur | +7.39 | 0.016 |

| 14LHG-04A | elemental sulfur | −6.18 | 0.009 |

| 13BT5-27-Є2a | anhydrite | +34.93 | 0.004 |

| 12BT5-02-Є2a | anhydrite | +24.43 | 0.018 |

| 12BT5-07-Є2a | anhydrite | +29.76 | 0.013 |

| 12BT5-08-Є2a | anhydrite | +35.44 | 0.009 |

| 13BT5-32-Є2a | anhydrite | +34.23 | 0.020 |

| 13BT5-37-Є1w | anhydrite | +31.30 | 0.015 |

| 13BT5-40-Є1w | anhydrite | +33.10 | 0.012 |

| 13BT5-42-Є1w | anhydrite | +35.33 | 0.009 |

| 13BT5-46-Є1w | anhydrite | +33.46 | 0.018 |

| 13BT5-50-Є1w | anhydrite | +34.47 | 0.008 |

| 13BT5-51-Є1w | anhydrite | +31.68 | 0.016 |

| Sample No. | Lithology | δ13CVPDB (‰) | δ18OVPDB (‰) | 87Sr/86Sr | ±2σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14TPL-11A | Host limestone | −0.67 | −6.54 | 0.708717 | 0.000006 |

| 14TPL-02B | Host limestone | −2.15 | −6.83 | 0.708570 | 0.000009 |

| 14TPL-12A | Host limestone | −0.50 | −6.20 | — | — |

| 14TPL-03B | Host limestone | −2.30 | −7.50 | — | — |

| YJK14-1 † | Limestone | −0.46 | −7.19 | — | — |

| YJK14-2 † | Limestone | −0.46 | −7.33 | — | — |

| YJK14-3 † | Limestone | −0.33 | −7.18 | — | — |

| YJK14-4 † | Limestone | −0.22 | −6.90 | — | — |

| YJK14-5 † | Limestone | −0.53 | −6.79 | — | — |

| YJK14-6 † | Limestone | −0.63 | −6.69 | — | — |

| YJK14-7 † | Limestone | −0.58 | −6.72 | — | — |

| YJK14-8 † | Limestone | −0.39 | −7.02 | — | — |

| YJK14-9 † | Limestone | −0.21 | −6.83 | — | — |

| YJK14-10 † | Limestone | −0.13 | −6.81 | — | — |

| YJK14-11 † | Limestone | −0.17 | −6.04 | — | — |

| YJK14-12 † | Limestone | −0.47 | −5.97 | — | — |

| YJK14-13 † | Limestone | −0.04 | −6.14 | — | — |

| YJK14-14 † | Limestone | −0.08 | −6.14 | — | — |

| YJK14-15 † | Limestone | +0.02 | −6.23 | — | — |

| YJK14-16 † | Limestone | −0.01 | −6.08 | — | — |

| YJK14-17 † | Limestone | +0.01 | −6.24 | — | — |

| YJK14-18 † | Limestone | −0.17 | −6.31 | — | — |

| 14LHG-01A’-2 | Laminar calcite | −6.20 | −12.70 | — | — |

| 14LHG-02A-1 | Laminar calcite | −5.90 | −12.70 | — | — |

| 14LHG-02A-2 | Laminar calcite | −6.40 | −12.90 | — | — |

| 14LHG-05B-1 | Laminar calcite | −6.10 | −10.30 | — | — |

| 14LHG-05B-2 | Laminar calcite | −3.10 | −11.00 | — | — |

| 14LHG-01A’ | Laminar calcite | −6.43 | −13.49 | 0.710769 | 0.000004 |

| 14LHG-02A | Laminar calcite | −5.66 | −12.69 | 0.710546 | 0.000015 |

| 09SC-82 # | Vein calcite 1 | −2.78 | −13.36 | 0.709238 | 0.000013 |

| 09SC-84 # | Vein calcite 1 | −2.42 | −11.07 | — | — |

| 09SC-87 # | Vein calcite 1 | −2.69 | −9.26 | — | — |

| 09SC-90 # | Vein calcite 1 | −3.02 | −10.53 | 0.709142 | 0.000013 |

| 09SC-91 # | Vein calcite 1 | −3.13 | −11.45 | 0.709132 | 0.000011 |

| 09SC-96 # | Vein calcite 1 | −2.75 | −13.49 | 0.709277 | 0.000013 |

| 09SC-98 # | Vein calcite 1 | −2.38 | −10.99 | 0.709407 | 0.000015 |

| 09SC-110 # | Vein calcite 1 | −2.40 | −11.62 | 0.709440 | 0.000012 |

| 09SC-112 # | Vein calcite 1 | −3.75 | −11.07 | 0.709001 | 0.000013 |

| 09SC-112 # | Vein calcite 2 | −2.85 | −13.01 | 0.709481 | 0.000013 |

| 09SC-110 # | Vein calcite 2 | −1.64 | −12.76 | 0.709630 | 0.000010 |

| TPL-1 § | Vug calcite | −1.66 | −16.13 | 0.710313 | — |

| TPL-2 § | Vug calcite | −2.32 | −17.39 | 0.710445 | — |

| TPL-3 § | Vug calcite | −2.72 | −14.99 | 0.709537 | — |

| TPL-4 § | Vug calcite | −2.66 | −15.50 | 0.709625 | — |

| TPL-5 § | Vug calcite | −4.98 | −13.30 | 0.709905 | — |

| 17-5 * | Travertine | −7.8 | −14.20 | — | — |

| 17-11 * | Travertine | −4.6 | −14.70 | — | — |

| 18-2 * | Travertine | −5.9 | −14.10 | — | — |

| TB001 * | Travertine | −5.6 | −13.50 | — | — |

| TB079 * | Travertine | −5.9 | −14.70 | — | — |

| TB001 * | Travertine | −5.2 | −14.00 | — | — |

| TB023 * | Travertine | −5.1 | −14.70 | — | — |

| TB006 * | Travertine | −5.2 | −12.90 | — | — |

| TB013 * | Travertine | −4.9 | −12.70 | — | — |

| TB022 * | Travertine | −4.6 | −11.60 | — | — |

| TB013 * | Travertine | −6.1 | −13.50 | — | — |

| TB016 * | Travertine | −6.4 | −13.10 | — | — |

| TB024 * | Travertine | −5 | −14.70 | — | — |

| TB080 * | Travertine | −5 | −14.20 | — | — |

| TB082 * | Travertine | −5.2 | −14.70 | — | — |

| TB099 * | Travertine | −5.4 | −15.50 | — | — |

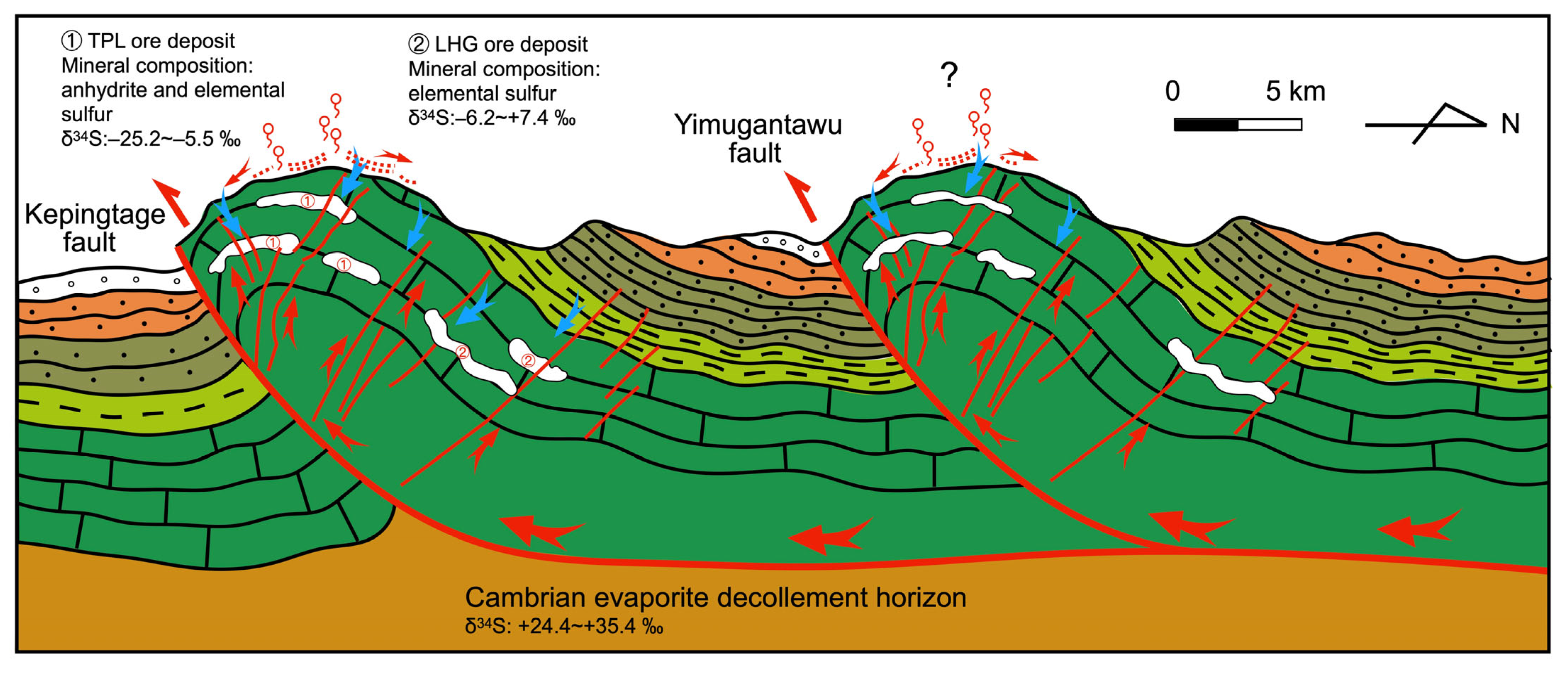

6. Discussion

6.1. Origin and Sources of Sulfur for Anhydrite and Elemental Sulfur Ore Deposits

6.2. Timing of BSR Reaction

6.3. Relationship with the Regional Tectonic Evolution

7. Conclusions

- 1.

- Many abandoned ore deposits occur in the Middle Ordovician carbonates and form dome-like geometries. Two types of sulfur-bearing minerals, elemental sulfur and anhydrite, are distinguished in the field. Elemental sulfur is present in both the TPL and LHG areas, whereas anhydrite exclusively occurs in the TPL area.

- 2.

- Elemental sulfur and anhydrite could have been formed through a multi-stage process involving bacterial sulfate reduction (BSR) and sulfur disproportionation in view of the scattered δ34S values. The required sulfate most likely ascended from the underlying Cambrian evaporites due to the progressive propagation of thrust nappes since the Cenozoic.

- 3.

- In the Keping area, extensive emplacement of sulfur-related ore deposits occurred while the infiltration of meteoric fluids was intensified, corresponding to the remote effects of the India–Eurasia collision. Expulsion fluids rich in SO42− migrated upward along the decollement horizon, forming an array of “sulfur springs”. Subsequently, microbial metabolism, re-oxidation and sulfur disproportionation led to the enrichment of elemental sulfur and anhydrite in paleo-karst cavities and fractured zones along the Keping overthrust front.

- 4.

- This study presents a useful example of the emplacement of deep-burial sulfate in a shallow environment controlled by bacterial metabolism in the thrust fault front, which could be very helpful for understanding the comprehensive process of BSR-induced ore deposits.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wijsman, J.W.N.; Middelburg, J.J.; Herman, P.M.J.; Böther, M.; Heip, C.H.R. Sulfur and iron speciation in surface sediments along the northwestern margin of the Black Sea. Mar. Chem. 2001, 74, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H.N.; Schulz, H.D. Large sulfur bacteria and the formation of phosphorite. Science 2005, 307, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.K. Evaporites: Sediments, Resources and Hydrocarbons, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 7, ISBN 978-3-540-32344-0. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Nakamura, K.; Takano, B.; Lilley, M.D.; Lupton, J.E.; Resing, J.A.; Roe, K.K. High SO2 flux, sulfur accumulation, and gas fractionation at an erupting submarine volcano. Geology 2011, 39, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindtke, J.; Ziegenbalg, S.B.; Brunner, B.; Rouchy, J.M.; Pierre, C.; Peckmann, J. Authigenesis of native sulphur and dolomite in a lacustrine evaporitic setting (Hellín basin, Late Mioncene, SE Spain). Geol. Mag. 2011, 148, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seewald, J.S.; Reeves, E.P.; Bach, W.; Saccocia, P.J.; Craddock, P.R.; Shanks III, W.C.; Sylva, S.P.; Pichler, T.; Rosner, M.; Walsh, E. Submarine venting of magmatic volatiles in the Eastern Manus Basin, Papua New Guinea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 163, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrado, A.L.; Brunner, B.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Peckmann, J. Formation of large native sulfur deposits does not require molecular oxgen. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Veigas, J.; Gimeno, D.; Pineda, V.; Cendón, D.I.; Sánchez-Román, M.; Artiaga, D.; Bembibre, G. The elemental sulfur ore deposit of Salmerón: Las Minas de Hellín basin (Late Miocene, SE Spain). Bol. Geol. Minero 2022, 133, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, M.E.; Parafiniuk, J. Methane-derived carbonates in native sulfur deposits: Stable isotope and trace element discrimination related to the transformation of aragonite to calcite. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 1998, 34, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckmann, J.; Paul, J.; Thiel, V. Bacterially mediated formation of diagenetic aragonite and native sulfur in Zechstein carbonates (Upper Permian, Central Germany). Sed. Geol. 1999, 126, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.R. Descriptive Model of Salt-Dome Sulfur and Contained-Sulfur Model for Salt-Dome Sulfur; US Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.; Luo, P.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, G.; Song, J. Geochemistry of fluorite and its genesis in Sickl area, Tarim Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2010, 28, 821–831, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Chen, D.; Qing, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, M.; Qian, Y. Hydrothermal alteration of dolostones in the Lower Ordovician, Tarim Basin, NW China: Multiple constraints from petrology, isotope geochemistry and fluid inclusion microthermometry. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2013, 46, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Pan, W.; Cai, C.; Jia, L.; Pan, L.; Wang, Τ.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y. Fluid mixing induced by hydrothermal activity in the Ordovician carbonates in Tarim Basin, China. Geofluids 2015, 15, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Han, F.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Zhang, T. Geological characteristics and sulfur and lead isotopes of the Kanling lead-zinc deposit, Southern Tianshan Mountains. Geol. China 2018, 45, 155–167, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Ye, Y. Geological and geochemical evidences for two sources of hydrothermal fluids found in Ordovician carbonate rocks in northwestern Tarim Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2012, 28, 2515–2524, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Mao, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Yuan, X.; Niu, Y.; Chen, Χ.; Huang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; et al. Discovery of the ancient Ordovician oil-bearing karst cave in Liuhuanggou, North Tarim Basin, and its significance. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2012, 55, 1406–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Hu, W.; Worden, R.H. Thermochemical sulphate reduction in Cambro-Ordovician carbonates in Central Tarim. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2001, 18, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Santosh, M.; Dong, C.; Yu, X. Permian bimodal dyke of Tarim Basin, NW China: Geochemical characteristics and tectonic implications. Gondwana Res. 2007, 12, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Ye, H. Diverse Permian magmatism in the Tarim Block, NW China: Genetically linked to the Permian Tarim mantle plume? Lithos 2010, 119, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Batt, G.E.; Li, Y. Permian flood basalts from the Tarim Basin, Northwest China: SHRIMP zircon U-Pb dating and geochemical characteristics. Gondwana Res. 2011, 20, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Q.; Hou, T.; Ke, S. Subducted slab-plume interaction traced by magnesium isotopes in the northern margin of the Tarim Large Igneous Province. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018, 489, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapponnier, P.; Molnar, P. Active faulting and tectonics in China. J. Geophys. Res. 1977, 82, 2905–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouac, J.P.; Tapponnier, P.; Bai, M.; You, H.; Wang, G. Active thrusting and folding along the northern Tien Shan and late Cenozoic rotation of the Tarim relative to Dzungaria and Kazakhstan. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 98, 6675–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, D.W.; McLean, J.K.; Bullen, M.; Abdrakhmatov, K.Y.; Miller, M.M. Partitioning of intermontane basins by thrust-related folding, Tien Shan, Kyrgyzstan. Basin Res. 1999, 11, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchfiel, B.C.; Brown, E.T.; Deng, Q.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Molnar, P.; Shi, J.; Wu, Z.; You, H. Crustal shortening on the margins of the Tien Shan, Xinjiang, China. Int. Geol. Rev. 1999, 41, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Nie, S.; Craig, P.; Harrison, T.M. Late Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the southern Chinese Tian Shan. Tectonics 1998, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, T.; Zhou, D.; Chang, E.; Graham, S.A.; Hendrix, M.S.; Sobel, E.R.; Carroll, A. Uplift, exhumation, and deformation in the Chinese Tian Shan. In Paleozoic and Mesozoic Tectonic Evolution of Central and Eastern Asia: From Continental Assembly to Intracontinental Deformation; Hendrix, M.S., Davis, G.A., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001; Volume 194, pp. 71–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Shu, L.; Wan, J.; Yang, W.; Su, J.; Zheng, B. Apatite fission track thermochronology of the Precambrian Aksu blueschist, NW China: Implications for thermos-tectonic evolution of the north Tarim basement. Gondwana Res. 2009, 16, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, J.; Qian, X.; Zheng, D. Analysis of fault structures in the Kalpin fault uplift, Tarim basin. Geol. China 2002, 29, 37–43, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Qu, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Ning, B.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yin, J. Geometry, kinematics and tectonic evolution of Kepingtage thrust system. Earth Sci. Front. 2003, 10, 142–152, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M.B.; Vincent, S.J. Late Cenozoic tectonics of the Kepingtage thrust zone: Interactions of the Tien Shan and Tarim Basin, northwest China. Tectonics 1999, 18, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhang, S.; Yong, T. Stratigraphy of the Tarim Basin; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2001; pp. 1–359. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Piper, J.D.A.; Sun, L.; Zhao, Q. New paleomagnetic results for Ordovician and Silurian of the Tarim Block, Northwest China and their paleogeographic implications. Tectonophysics 2019, 755, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J.A.D. A modified staining technique for carbonates in thin section. Nature 1965, 205, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Chen, D.; Zhou, X.; Qian, Y.; Tian, M.; Qing, H. Tectonically driven dolomitization of Cambrian to Lower Ordovician carbonates of the Quruqtagh area, north-eastern flank of Tarim Basin, north-west China. Sedimentology 2017, 64, 1079–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halas, S.; Shakur, A.; Krouse, H.R. A modified method of SO2 extraction from sulphates for isotopic analysis using NaPO3. Isotopenpraxis 1982, 18, 433–435. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, M.; Mayer, B.; Taylor, S.W. δ34S measurements on organic materials by continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2005, 19, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claypool, G.E.; Holser, W.T.; Kaplan, I.R.; Sakai, H.; Zak, I. The age curve of sulfur and oxygen isotopes in marine sulfate and their mutual interpretation. Chem. Geol. 1980, 28, 190–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampschulte, A.; Strauss, H. The sulfur isotopic evolution of Phanerozoic seawater based on the analysis of structurally substituted sulfate in carbonates. Chem. Geol. 2004, 204, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, H.; Veizer, J. Oxygen and carbon isotopic composition of Ordovician brachiopods: Implications for coeval seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1994, 58, 4429–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veizer, J.; Ala, D.; Azmy, K.; Bruckschen, P.; Buhl, D.; Bruhn, F.; Carden, G.A.F.; Diener, A.; Ebneth, S.; Godderis, Y.; et al. 87Sr/86Sr, δ13C and δ18O evolution of Phanerozoic seawater. Chem. Geol. 1999, 161, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, W.H.; Denison, R.E.; Hetherington, E.A.; Koepnick, R.B.; Nelson, H.F.; Otto, J.B. Variation of seawater 87Sr/86Sr throughout Phanerozoic time. Geology 1982, 10, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Munnecke, A. Ordovician stable carbon isotope stratigraphy in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016, 458, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañez, I.P.; Banner, J.L.; Osleger, D.A.; Borg, L.E.; Bosserman, P.J. Integrated Sr isotope variations and sea-level history of Middle to Upper Cambrian platform carbonates: Implications for the evolution of Cambrian seawater 87Sr/86Sr. Geology 1996, 24, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañez, I.P.; Osleger, D.A.; Banner, J.L.; Mack, L.E.; Musgrove, M. Evolution of the Sr and C isotope composition of Cambrian oceans. GSA Today 2000, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, H.; Barnes, C.R.; Buhl, D.; Veizer, J. The strontium isotopic composition of Ordovician and Silurian brachiopods and conodonts: Relationships to geological events and implications for coeval seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1998, 62, 1721–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campell, A.R.; Larson, P.B. Introduction to stable isotope applications in hydrothermal systems. Rev. Econ. Geol. 1998, 10, 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Shanks III, W.C. Stable isotopes in seafloor hydrothermal systems: Vent fluids, hydrothermal deposits, hydrothermal alteration, and microbial processes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2001, 43, 469–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplin, A.C.; Coleman, M.L. Sour gas and water chemistry of the Bridport sands reservoir Wytch Farm, UK. In The Geochemistry of Reservoirs; Cubit, J.M., England, W.A., Eds.; Geological Society Special Publication: London, UK, 1995; Volume 86, pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C.; Amrani, A.; Worden, R.H.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, T.; Gvirtzman, Z.; Li, H.; Said-Ahmad, W.; Jia, L. Sulfur isotopic compositions of individual organosulfur compounds and their genetic links in the Lower Paleozoic petroleum pools of the Tarim Basin, NW China. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 182, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Fakhraee, M.; Cai, C.; Worden, R.H. Sulfur cycling during progressive burial in sulfate-rich marine carbonates. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst 2020, 21, e2020GC009383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Lü, X.; Zhang, J.; Hou, G.; Liu, R.; Yan, H.; Li, T. Distribution characteristics and significance of hydrocarbon shows to petroleum geology in Kalpin area, NW Tarim Basin. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2012, 30, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Worden, R.H.; Cai, C.; Shen, A.; Crowley, S.F. Diagenesis of an evaporite-related carbonate reservoir in deeply buried Cambrian strata, Tarim Basin, northwest China. AAPG Bull. 2018, 102, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E.; Thamdrup, B. The production of 34S depleted sulfide during bacterial disproportionation of elemental sulfur. Science 1994, 266, 1973–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E.; Teske, A. Late Proterozoic rise in atmospheric oxygen concentration inferred from phylogenetic and sulphur-isotope studies. Nature 1996, 382, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habicht, K.S.; Canfield, D.E.; Rethmeier, J. Sulfur isotope fractionation during bacterial reduction and disproportionation of thiosulfate and sulfate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1998, 62, 2585–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machel, H.G.; Krouse, H.R.; Sassen, R. Products and distinguishing criteria of bacterial and thermochemical sulfate reduction. Appl. Geochem. 1995, 10, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H.; Smalley, P.C. H2S-producing reactions in deep carbonate gas reservoirs: Khuff formation, Abu Dhabi. Chem. Geol. 1996, 133, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Worden, R.H.; Bottrell, S.H.; Wang, L.; Yang, C. Thermochemical sulphate reduction and the generation of hydrogen sulphide and thiols (mercaptans) in Triassic carbonate reservoirs from the Sichuan basin, China. Chem. Geol. 2003, 202, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Xie, Z.; Worden, R.H.; Hu, G.; Wang, L.; He, H. Methane-dominated thermochemical sulphate reduction in the Triassic Feixianguan Formation East Sichuan Basin, China: Towards prediction of fatal H2S concentrations. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2004, 21, 1265–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Jin, Z.; Wang, F. The effect of the complex geothermal field based on the multi-structure evolution to hydrocarbon generation: A case of Tazhong area in Tarim Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 1997, 15, 142–144, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Qiu, N.; Jin, Z.; He, Z. Geothermal history in the Tarim Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2005, 26, 613–617, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Muchez, P.; Nielsen, P.; Sintubin, M.; Lagrou, D. Conditions of meteoric calcite formation along a Variscan fault and their possible relation to climatic evolution during the Jurassic-Cretaceous. Sedimentology 1998, 45, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Qing, H.; Yang, C. Multistage hydrothermal dolomites in the Middle Devonian (Givetian) carbonates from the Guilin area, South China. Sedimentology 2004, 51, 1029–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Land, L.S. Early Ordovician Cool Creek dolomite, Middle Arbuckle Group, Slick Hills, SW Oklahoma, U.S.A.: Origin and modification. J. Sed. Res. 1991, 61, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, D. Deep dissolution of Cambrian-Ordovician carbonates in the Northern Tarim Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 1994, 12, 66–71, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Hu, J.; Zilio, L.D.; Tang, M.; Li, K.; Hu, X. India-Eurasia convergence speed-up by passive-margin sediment subduction. Nature 2024, 635, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Qiu, N.; Li, J. Tectono-thermal evolution of the northwestern edge of the Tarim Basin in China: Constraints from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronology. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 61, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J. Fluids expelled tectonically from orogenic belts: Their role in hydrocarbon migration and other geologic phenomena. Geology 1986, 14, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machel, H.G.; Cavell, P.A. Low-flux, tectonically-induced squeegee fluid flow (“hot flash”) into the Rochy Mountain Foreland Basin. Bull. Can. Petrol. Geol. 1999, 47, 510–533. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, G.J. The microbiomes of deep-sea hydrothermal vents: Distributed globally, shaped locally. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, S.; Shao, Z. Sulfurimonas xiamenensis sp. nov. and Sulfurimonas lithotrophica sp. nov., hydrogen- and sulfur-oxidizing chemolithoautotrophs within the Epsilonproteobacteria isolated from coastal sediments, and an emended description of the genus Sulfurimonas. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Μicrobiol. 2020, 70, 2657–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, S.; Luo, Y.; Han, J.; Chen, D. Constraints on the Origin of Sulfur-Related Ore Deposits in NW Tarim Basin, China: Integration of Petrology and C-O-Sr-S Isotopic Geochemistry. Minerals 2025, 15, 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121265

Dong S, Luo Y, Han J, Chen D. Constraints on the Origin of Sulfur-Related Ore Deposits in NW Tarim Basin, China: Integration of Petrology and C-O-Sr-S Isotopic Geochemistry. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121265

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Shaofeng, Yuhang Luo, Jun Han, and Daizhao Chen. 2025. "Constraints on the Origin of Sulfur-Related Ore Deposits in NW Tarim Basin, China: Integration of Petrology and C-O-Sr-S Isotopic Geochemistry" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121265

APA StyleDong, S., Luo, Y., Han, J., & Chen, D. (2025). Constraints on the Origin of Sulfur-Related Ore Deposits in NW Tarim Basin, China: Integration of Petrology and C-O-Sr-S Isotopic Geochemistry. Minerals, 15(12), 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121265