Hybrid Second-Order Iterative Algorithm for Orthogonal Projection onto a Parametric Surface

Abstract

1. Introduction

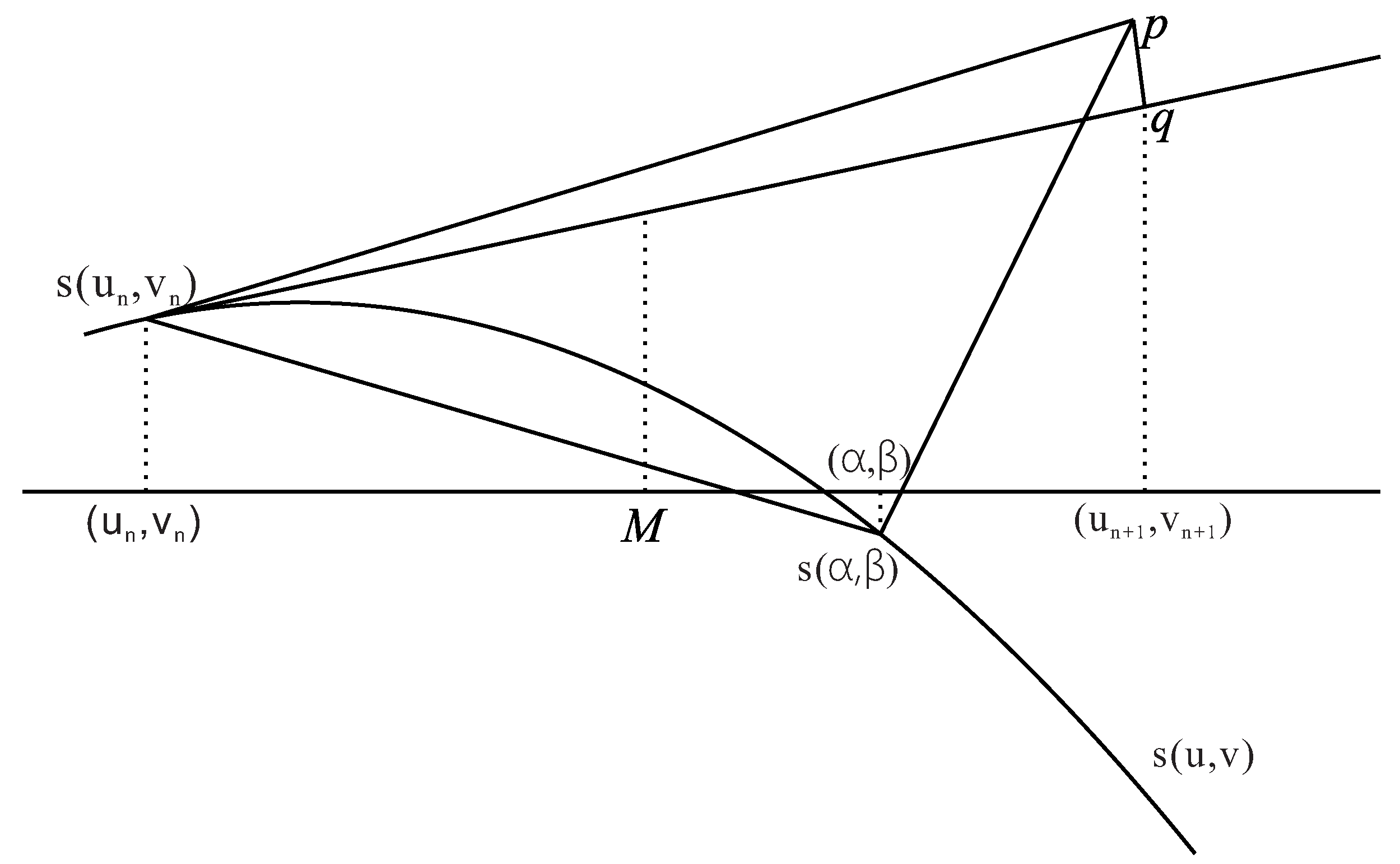

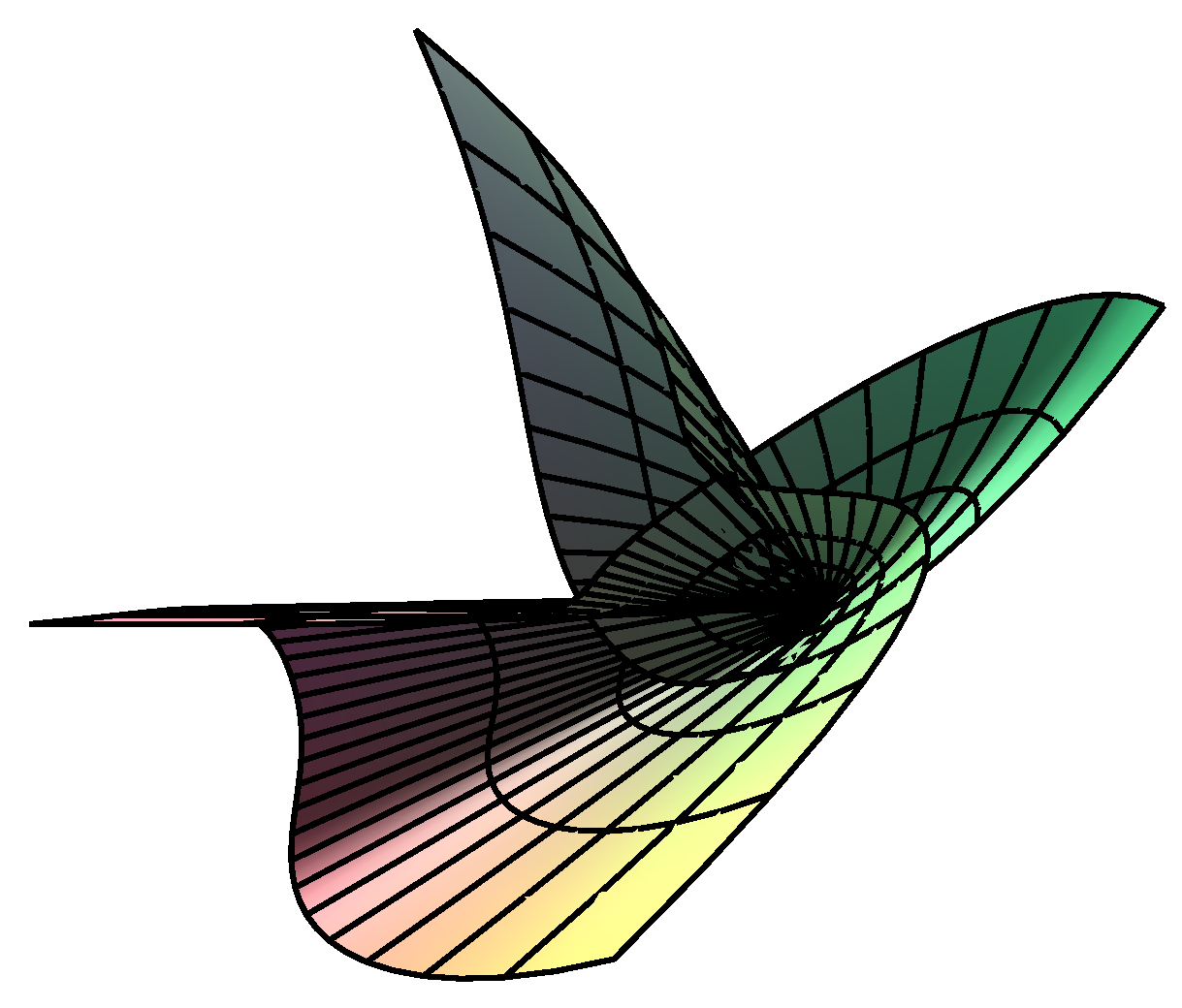

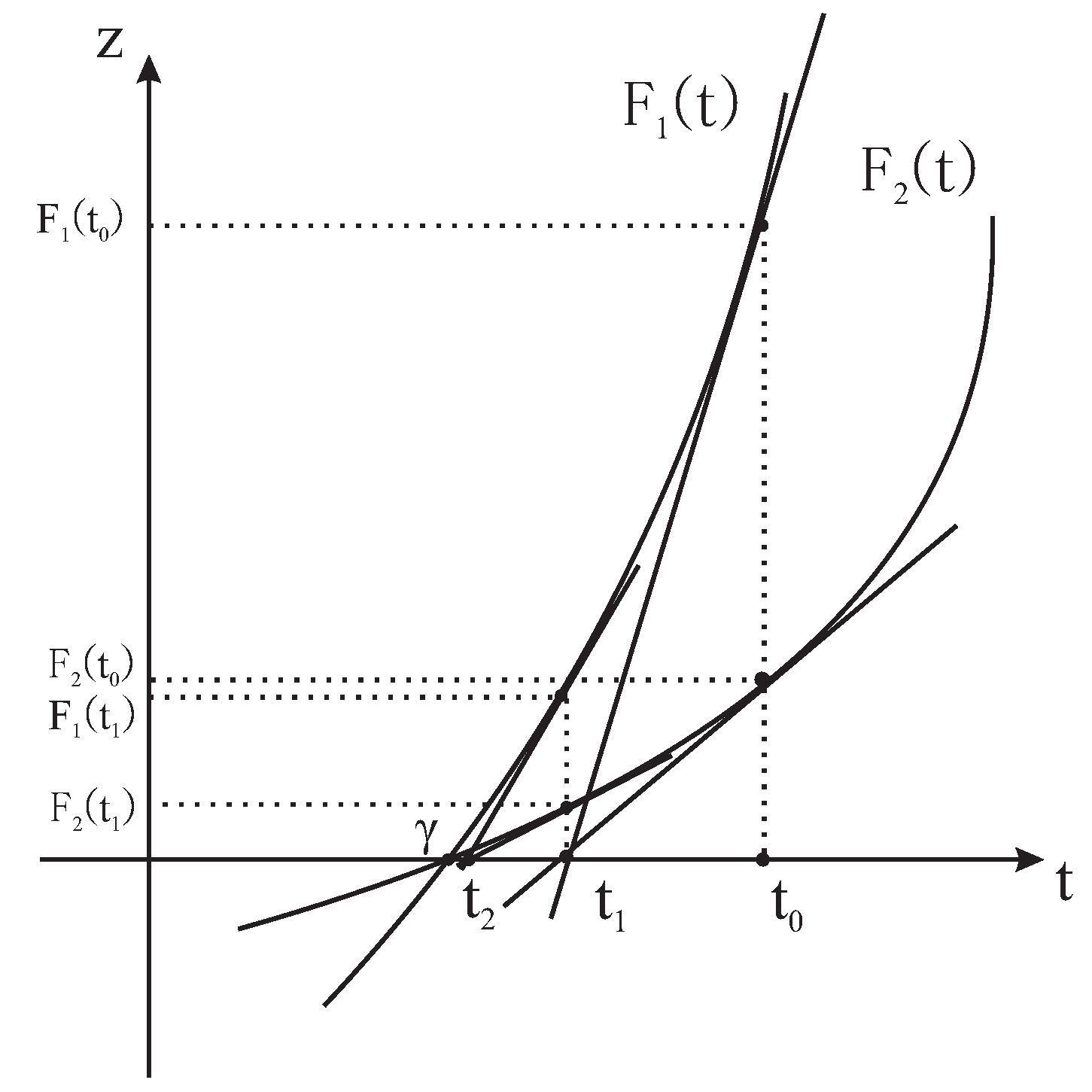

2. Convergence Analysis for the First-Order Method

3. Numerical Examples

4. The Improved Algorithm

4.1. Counterexamples

4.2. The Improved Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: The hybrid second-order algorithm. |

| Input: Input the initial iterative parametric value , parametric surface and test point p. |

| Output: Output the final iterative parametric value. |

|

| . |

| If |

| { |

| Using Newton’s second-order iterative Formula (22), compute |

| until the norm of difference between the former and |

| the latter is near 0(), then end this algorithm. |

| } |

| Else { |

| go to Step 2. |

| } |

4.3. Convergence Analysis for the Improved Algorithm

4.4. Numerical Experiments

- (1)

- Divide a parametric region of a parametric surface into sub-regions , where .

- (2)

- Randomly select an initial iterative parametric value in each sub-region.

- (3)

- For each initial iterative parametric value, holding other initial iterative parametric values fixed, use the hybrid second-order iterative algorithm and iterate until it converges. Let us assume that the converged iterative parametric values are , respectively.

- (4)

- Compute the local minimum distances , where .

- (5)

- Compute the global minimum distance . If we try to find all solutions as soon as possible, divide a parametric region of parametric surface into sub-regions , where such that M is very large.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.L.; Hewitt, W.T. Point inversion and projection for NURBS curve and surface: Control polygon approach. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2003, 20, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.P.; Wang, W.P.; Sun, J.G. Control point adjustment for B-spline curve approximation. Comput. Aided Des. 2004, 36, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Cohen, E. A Framework for efficient minimum distance computations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intemational Conference on Robotics & Automation, Leuven, Belgium, 20 May 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Piegl, L.; Tiller, W. Parametrization for surface fitting in reverse engineering. Comput. Aided Des. 2001, 33, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegna, J.; Wolter, F.E. Surface curve design by orthogonal projection of space curves onto free-form surfaces. ASME Trans. J. Mech. Design 1996, 118, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besl, P.J.; McKay, N.D. A method for registration of 3-D shapes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1992, 14, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-C.; Yong, J.-H.; Yang, Y.-J.; Liu, X.-M. Algorithm for orthogonal projection of parametric curves onto B-spline surfaces. Comput.-Aided Des. 2011, 43, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.M.; Wallner, J. A second order algorithm for orthogonal projection onto curves and surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2005, 22, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortenson, M.E. Geometric Modeling; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.M.; Sherbrooke, E.C.; Patrikalakis, N. Computation of stationary points of distance functions. Eng. Comput. 1993, 9, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Cohen, E. Distance extrema for spline models using tangent cones. In Proceedings of the 2005 Conference on Graphics Interface, Victoria, BC, Canada, 9–11 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Limaien, A.; Trochu, F. Geometric algorithms for the intersection of curves and surfaces. Comput. Graph. 1995, 19, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, E.; Royset, J.O. Algorithms with adaptive smoothing for finite minimax problems. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2003, 119, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrikalakis, N.; Maekawa, T. Shape Interrogation for Computer Aided Design and Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Selimovic, I. Improved algorithms for the projection of points on NURBS curves and surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2006, 23, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Lyche, T.; Riesebfeld, R. Discrete B-splines and subdivision techniques in computer-aided geometric design and computer graphics. Comput. Graph. Image Proc. 1980, 14, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegl, L.; Tiller, W. The NURBS Book; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-M.; Yang, L.; Yong, J.-H.; Gu, H.-J.; Sun, J.-G. A torus patch approximation approach for point projection on surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2009, 26, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Xin, Q.; Wu, Z.N.; Zhang, M.S.; Zhang, Q. A geometric strategy for computing intersections of two spatial parametric curves. Vis. Comput. 2013, 29, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-J. Minimum distance between a canal surface and a simple surface. Comput.-Aided Des. 2003, 35, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Jiang, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.C. An efficient surface-surface intersection algorithm based on geometry characteristics. Comput. Graph. 2004, 28, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-D.; Ma, W.Y.; Xu, G.; Paul, J.-C. Computing the Hausdorff distance between two B-spline curves. Comput.-Aided Des. 2010, 42, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-D.; Chen, L.Q.; Wang, Y.G.; Xu, G.; Yong, J.-H.; Paul, J.-C. Computing the minimum distance between two Bézier curves. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2009, 229, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, B.R.; Chunduru, A.; Tiwari, R.; Gupta, A.; Muthuganapathy, R. Footpoint distance as a measure of distance computation between curves and surfaces. Comput. Graph. 2014, 38, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-D.; Yong, J.-H.; Wang, G.Z.; Paul, J.-C.; Xu, G. Computing the minimum distance between a point and a NURBS curve. Comput.-Aided Des. 2008, 40, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-D.; Xu, G.; Yong, J.-H.; Wang, G.Z.; Paul, J.-C. Computing the minimum distance between a point and a clamped B-spline surface. Graph. Model. 2009, 71, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.-T.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.-S.; Elber, G. Efficient point-projection to freeform curves and surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2012, 29, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Sakkalis, T. Orthogonal projection of points in CAD/CAM applications: An overview. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2014, 1, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E. On the curvature of curves and surfaces defined by normal forms. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1999, 16, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoschek, J.; Lasser, D. Fundamentals of Computer Aided Geometric Design; A.K. Peters, Ltd.: Natick, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.M.; Sun, J.G.; Jin, T.G.; Wang, G.Z. Computing the parameter of points on NURBS curves and surfaces via moving affine frame method. J. Softw. 2000, 11, 49–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Melmant, A. Geometry and convergence of eulers and halleys methods. SIAM Rev. 1997, 39, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, J.F. A Class of globally convergent iteration functions for the solution of polynomial equations. Math. Comput. 1966, 20, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, R.L.; Faires, J.D. Numerical Analysis, 9th ed.; Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Piegl, L.A. Ten challenges in computer-aided design. Comput.-Aided Des. 2005, 37, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1,−2) | (−2,2) | (−2,−2) | (0,0) | (1,1) | (−2,−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 142,941 | 132,544 | 39,857 | 135,606 | 133,859 | 40,180 |

| 2 | 132,044 | 155,592 | 38,792 | 133,112 | 160,154 | 45,392 |

| 3 | 133,380 | 132,947 | 38,952 | 181,563 | 132,472 | 46,018 |

| 4 | 132,869 | 140,089 | 43,009 | 132,702 | 133,377 | 40,517 |

| 5 | 134,137 | 134,045 | 40,559 | 134,416 | 125,638 | 39,725 |

| 6 | 136,875 | 140,145 | 43,830 | 146,907 | 132,289 | 41,029 |

| 7 | 133,808 | 133,415 | 39,890 | 132,827 | 133,388 | 40,389 |

| 8 | 132,753 | 148,692 | 41,072 | 133,869 | 135,500 | 44,930 |

| 9 | 132,332 | 153,146 | 38,907 | 1373,30 | 141,663 | 41,428 |

| 10 | 136,460 | 147,361 | 45,462 | 132,184 | 142,250 | 44,384 |

| Average time | 134,760 | 141,798 | 41,033 | 140,051 | 137,059 | 42,399 |

| (1,1) | (2,2) | (2,0) | (1,2) | (2,1) | (0,2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 567,161 | 492,909 | 550,174 | 349,185 | 384,516 | 4,920,804 |

| 2 | 575,759 | 521,233 | 492,835 | 385,293 | 390,527 | 523,743 |

| 3 | 484,250 | 381,832 | 487,414 | 389,792 | 502,568 | 498,248 |

| 4 | 499,588 | 346,864 | 434,103 | 494,559 | 436,330 | 536,043 |

| 5 | 456,397 | 433,893 | 463,222 | 501,650 | 493,197 | 434,355 |

| 6 | 517,495 | 433,521 | 440,372 | 435,692 | 399,478 | 362,600 |

| 7 | 488,340 | 452,431 | 489,985 | 439,752 | 471,909 | 524,395 |

| 8 | 499,700 | 475,481 | 481,180 | 433,924 | 473,261 | 522,088 |

| 9 | 438,441 | 386,592 | 438,255 | 503,681 | 366,078 | 469,647 |

| 10 | 481,179 | 483,391 | 532,150 | 524,016 | 349,502 | 517,721 |

| Average time | 500,831 | 440,815 | 480,969 | 445,755 | 426,737 | 488,092 |

| (1,−2) | (−2,2) | (−2,−2) | (0,0) | (1,1) | (−2,−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 321,617 | 298,224 | 89,679 | 305,115 | 301,183 | 90,406 |

| 2 | 297,101 | 350,084 | 87,282 | 299,503 | 360,347 | 102,133 |

| 3 | 300,105 | 299,131 | 87,643 | 408,517 | 298,064 | 103,542 |

| 4 | 298,957 | 315,201 | 96,771 | 298,580 | 300,100 | 91,164 |

| 5 | 301,810 | 301,603 | 91,259 | 302,437 | 282,687 | 89,383 |

| 6 | 307,970 | 315,327 | 98,618 | 330,541 | 297,651 | 92,317 |

| 7 | 301,068 | 300,185 | 89,754 | 298,861 | 300,125 | 90,876 |

| 8 | 298,695 | 334,557 | 92,413 | 301,206 | 304,875 | 101,094 |

| 9 | 297,748 | 344,580 | 87,542 | 308,994 | 318,743 | 93,215 |

| 10 | 307,036 | 331,563 | 102,291 | 297,415 | 320,064 | 99,865 |

| Average time | 303,210.7 | 319,045.5 | 92,325.2 | 315,116.9 | 308,383.9 | 95,399.5 |

| (1,1) | (2,2) | (2,0) | (1,2) | (2,1) | (0,2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,276,113 | 1,109,047 | 1,237,892 | 785,668 | 865,161 | 1,107,181 |

| 2 | 1,295,460 | 1,172,776 | 1,108,880 | 866,911 | 878,687 | 1,178,422 |

| 3 | 1,089,563 | 859,122 | 1,096,683 | 877,034 | 1,130,779 | 1,121,060 |

| 4 | 1,124,075 | 780,446 | 976,732 | 1,112,759 | 981,744 | 1,206,097 |

| 5 | 1,026,895 | 976,261 | 1,042,251 | 1,128,713 | 1,109,694 | 977,300 |

| 6 | 1,164,364 | 975,423 | 990,837 | 980,309 | 898,827 | 815,852 |

| 7 | 1,098,765 | 1,017,971 | 1,102,468 | 989,442 | 1,061,796 | 1,179,891 |

| 8 | 1,124,327 | 1,069,834 | 1,082,657 | 976,331 | 1,064,839 | 1,174,699 |

| 9 | 986,493 | 869,833 | 986,075 | 1,133,284 | 823,676 | 1,056,707 |

| 10 | 1,082,654 | 1,087,631 | 1,197,338 | 1,179,038 | 786,381 | 1,164,873 |

| Average time | 1,126,871 | 991,834.4 | 1,082,181 | 1,002,949 | 960,158.4 | 1,098,208 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, Z.; Hou, L.; Liang, J.; Li, Q. Hybrid Second-Order Iterative Algorithm for Orthogonal Projection onto a Parametric Surface. Symmetry 2017, 9, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9080146

Li X, Wang L, Wu Z, Hou L, Liang J, Li Q. Hybrid Second-Order Iterative Algorithm for Orthogonal Projection onto a Parametric Surface. Symmetry. 2017; 9(8):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9080146

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaowu, Lin Wang, Zhinan Wu, Linke Hou, Juan Liang, and Qiaoyang Li. 2017. "Hybrid Second-Order Iterative Algorithm for Orthogonal Projection onto a Parametric Surface" Symmetry 9, no. 8: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9080146

APA StyleLi, X., Wang, L., Wu, Z., Hou, L., Liang, J., & Li, Q. (2017). Hybrid Second-Order Iterative Algorithm for Orthogonal Projection onto a Parametric Surface. Symmetry, 9(8), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9080146