Abstract

We present a hypothesis for a mechanism involving self-organization of small functional units that leads to organ-level synchronization of uterine contractions in human labor. This view is in contrast to the long-held presumption that the synchronized behavior of the uterus is subject to well-defined internal organization (as is found in the heart) that exists prior to the onset of labor. The contractile units of the uterus are myocytes, which contract in response to both mechanical stretch and electrical stimulation. Throughout pregnancy progesterone maintains quiescence by suppression of “contraction-associated proteins” (CAPs). At the end of pregnancy a functional withdrawal of progesterone and an increasingly estrogenic environment leads to an increase in the production of CAPs. One CAP of particular importance is connexin 43, which creates gap junctions between the myocytes that cause them to become electrically coupled. The electrical connectivity between myocytes, combined with an increase in intrauterine pressure at the end of pregnancy shifts the uterus towards an increasingly unstable critical point, characterized by irregular, uncoordinated contractions. We propose that synchronous, coordinated contractions emerge from this critical point through a process of self-organization, and that the search for a uterine pacemaker has been unfruitful for the sole reason that it is non-existent.

1. Introduction

One of the outstanding mysteries of reproductive biology is how the pregnant uterus converts from a quiet home and garden where the fetus is protected and grows, to a cruel landlord that evicts the tenant regardless of time of day or holiday. Two aspects have been particularly elusive: the timing of the onset of labor, and the mechanism underlying the organ-level synchronization of uterine contractions in established labor. This paper describes a physiological framework that links these seemingly disparate aspects into a coherent model that is less enigmatic than when each is considered separately.

Here we will present a picture of organ-level uterine function that has recently emerged, and anticipate that detailed scrutiny will identify where finer brushstrokes are necessary. It is clear that symmetry is reduced in the transition from the quiescent, non-contracting state of the uterus to the highly organized, phasic contractions seen in established labor. We will describe how hormonal signaling from the fetus and placenta at the end of pregnancy shifts the uterus from its stable, quiescent state to an increasingly unstable critical point, and simultaneously brings about the production of the components necessary for synchronized contractions. We will describe four distinct transitions that occur in the progression from uterine quiescence to active labor. The organization of these components in the final step of organ-level signaling is unique to the uterus. We will review the emergence of self-organization and how the reduction of symmetry results from the expression of a relatively small number of proteins just prior to the onset of labor.

2. Myocytes—the Smallest Contractile Units of the Uterus

The forces underlying uterine contractions originate with the billions of smooth muscle cells (myocytes) that comprise the uterus. Each myocyte is capable of contraction, and it is how these billions of cells are coordinated to form a synchronized uterine contraction that is enigmatic. The process of myocyte contraction may be summarized as follows: (1) normally myocytes have a resting membrane potential near −50 mV, but a complex of events at the membrane causes depolarization to 0 mV [1], leading to the opening of voltage-activated ion channels and the entry of Ca2+ into the cell; (2) the influx of Ca2+ initiates a sequence of events that results in polypeptide polymers called actin and myosin to interact and shorten, reducing the length of the cell and increasing tension in the wall of the uterus [2,3,4,5]. Myocyte contraction can be stimulated by two events: stretching and the depolarization of neighboring cells. This energy-intensive process produces a contraction that cannot be maintained indefinitely—after a period of contraction (typically 20–40 s for uterine myocytes) the cell exhibits a refractory period, during which it is unresponsive to both mechanical and electrical stimuli. The refractory period may be considered as a process of recharging the batteries, in which potassium ions (K+) and sodium ion (Na+) are pumped across the cell membrane against an electrical gradient, and typically lasts two to three min.

While the main portion of the uterus houses the fetus, the cervix, is the portion that opens to create a passage through which the baby is born. The cervix has a firm consistency since it must hold the fetus inside for the vast majority of the pregnancy. In labor, the uterine contractions raise intrauterine pressure, and high pressures caused by strong contractions are required to dilate the cervix [6]. However, during a strong contraction, blood flow to the fetus is greatly reduced, inhibiting exchange of fetal waste products for nutrients. This problem is mitigated by the uterus spending more time resting than contracting, which justifies the phasic pattern of labor contractions. In active labor, each contraction lasts ~60 s, and the time between contractions is 2–4 min.

To maximally raise intrauterine pressure, it is necessary that the whole of the uterus contract in a coordinated manner. If some portion of the uterine wall were to remain relaxed and not participate in a contraction, that portion would respond to the intrauterine pressure (caused by contraction of the other portions of the uterus) and bulge because of the viscoelastic properties of smooth muscle. This would significantly blunt rises of intrauterine pressure and be quite counterproductive to cervical dilation. Therefore, coordinating the entirety of the uterine wall into synchronous contractile activity is quintessential for labor [7].

3. From Quiescence to Critical Point—the Role of Sex Hormones and Contraction-Associated Proteins

Progesterone is the key hormone of pregnancy. Its levels rise throughout pregnancy, falling only as the placenta is delivered. An important role of progesterone prior in the early stages of pregnancy is to act as a “brake” on myocyte contractility [8]. This occurs through a number of mechanisms, including the suppression of production of a number of proteins collectively known as “contraction-associated proteins”, or CAPs. Transitioning the uterus from not-in-labor to in-labor occurs by increasing myocyte content of CAPs in response to an increasingly estrogenic environment at the very end of pregnancy and a withdrawal of the biological activity of the progesterone [9]. It is apparent that maternal and fetal production of progesterone and estrogen strongly influence the onset of labor [10,11].

4. The Emergence of Synchronized Contractions—the Appearance and Synchronization of Syncytia

Recalling that myocytes contract in response to both stretch and electrical stimulation, one cell’s depolarization can also cause depolarization of adjacent cells if the cells are electrically connected by junctions made of specific proteins called connexin 43 (Cx43; these proteins are also called gap junctions) [12,13]. Cx43 is an important CAP because when inserted into the cell membrane of adjacent myocytes to form junctions, myocytes can become tightly electrically coupled over relatively long distances (1–2 cm). Cx43 junctions also allow passage of small, uncharged molecules, which has the effect of allowing cells some communication via metabolic messengers. The production of Cx43 is opposed by progesterone, and increases in response to the increasingly estrogenic environment at the end of pregnancy. The transition from low to high expression of Cx43 increases tissue-level communication and synchronization of the activities of contiguous myocytes. Under these conditions many of the key functional effects of the cell membrane are mitigated, which brings into question the definition of an individual myocyte [14,15]. Many feel the highly coupled system should be thought of as a syncytium, with functional characteristics that differ from a collection of individual cells.

While the syncytium can be envisioned as a tissue-level structure, additional levels of organization are required at the organ-level as discussed above. It has previously been assumed without convincing supporting data that electrical signaling was also the mechanism for organ-level signaling. In 2005, work at the University of Arkansas produced data indicating the contrary—that organ-level signaling could not be by electrical signaling [16]. Using an array of superconducting quantum interference devices, they demonstrated that there was no pacemaker and that contractions could move across the uterus faster than electrical propagation allows. As an alternative mechanism it has been proposed that the wall of the contracting pregnant uterus is organized into regions approximately 8 cm × 8 cm [7]. Following the activity of one region, additional regions are recruited, but most often at distant locations. Recruitment continues with this non-contiguous mechanism until the entire uterine wall is active at the peak of the contraction. This mechanism does not involve transmission of electrical impulses, as interconnecting activities between regions would have been occasionally identified. So how does the first region recruit the others?

This enigmatic mechanism can be explained by recalling that smooth muscle can be induced to contract by mechanical stimulation in addition to electrical. As described above with the bulging of the portion of the uterus that was recalcitrant to contraction, pressure rises will stretch the wall, thereby providing mechanical stimulation. The mechanical stimulation-contraction mechanism, or mechanotransduction, was first proposed by Arpad Csapo [17] in 1970, although the refinement that incorporates this with electrical mechanisms has only been recently developed. The key link to mechanotransduction is the same force that dilates the cervix-intrauterine pressure. Through the Law of Laplace, the relationship between pressure and wall tension can be quantified [7].

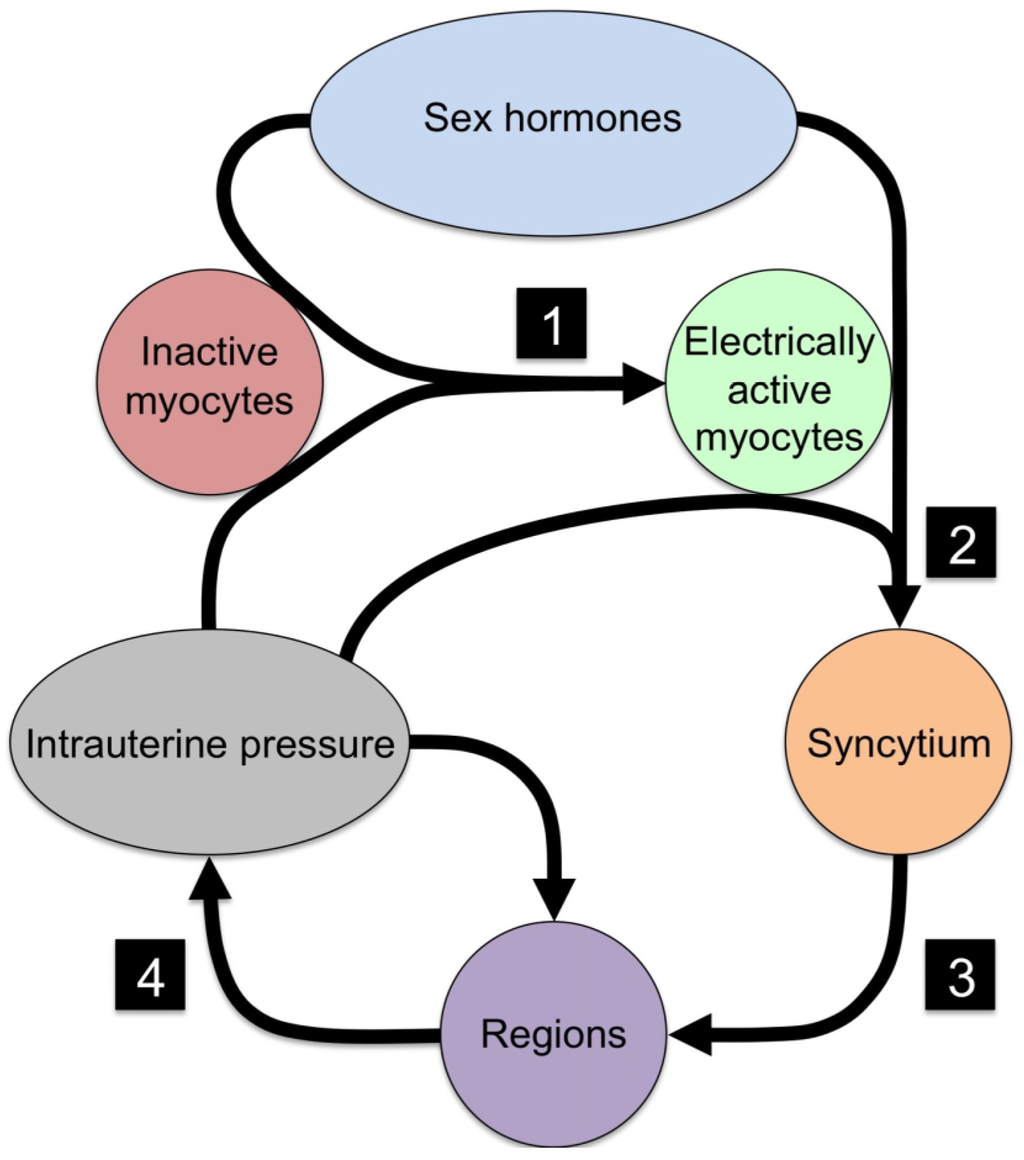

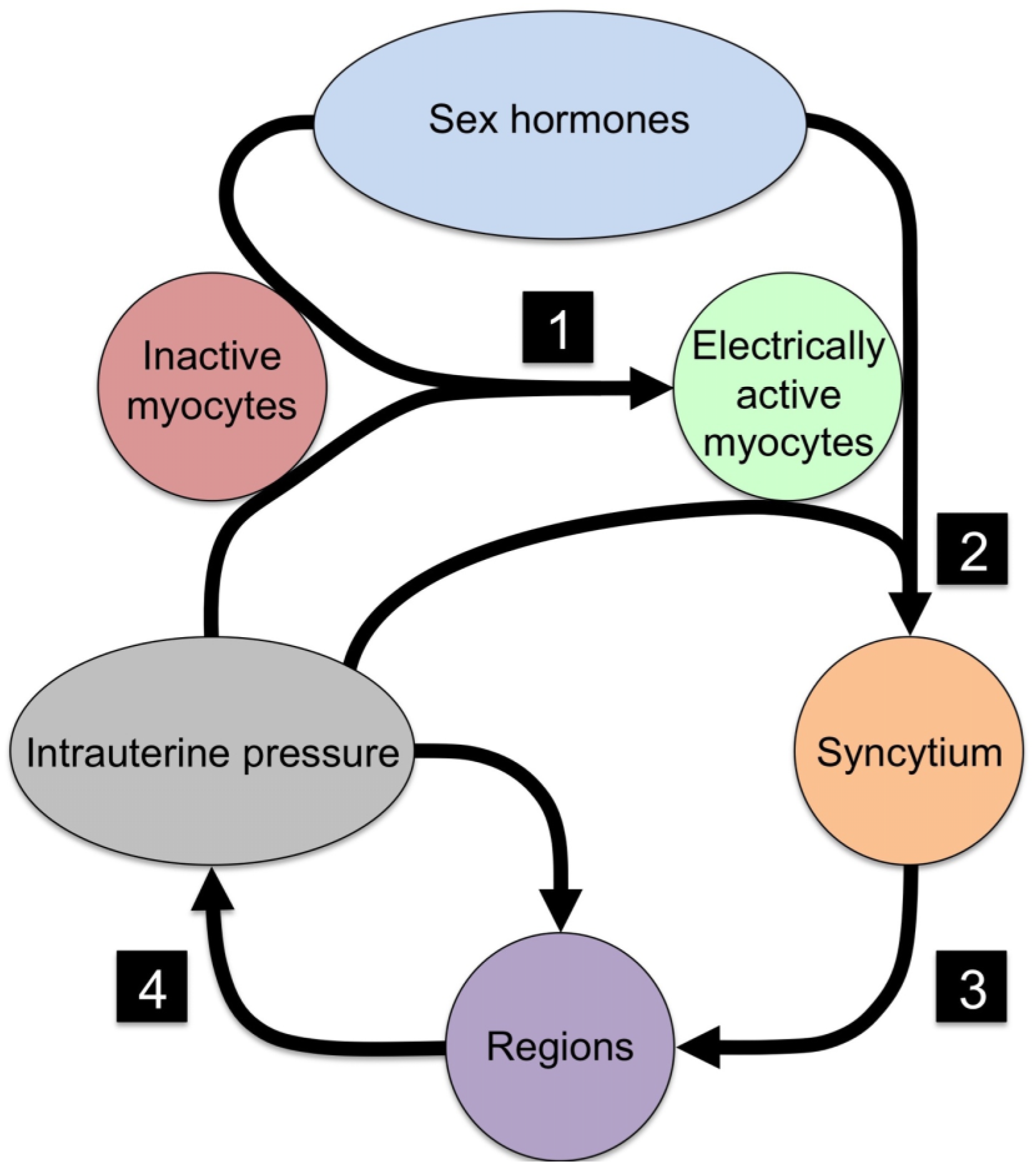

Summarizing the dual signaling mechanism—normally quiescent myocytes are converted to spontaneously active cells by sex hormone-dependent expression of select CAPs. Syncytial units are created by expression of the CAP Cx43. These units have an inherent oscillation frequency that is dependent on the shared resting membrane potential and the expression of ion channels that may be distributed throughout the unit. If nearby syncytia have similar frequencies of oscillation, these units will couple and contiguous syncytia will express coordinated electrical depolarizations. In this manner, regional activities are expressed, but electrical coupling does not reach beyond ~8 cm in any direction. This process results in the contractile activity of one region. In a limited sense, this region is the pacemaker of that specific contraction, but should not be considered the pacemaker of the uterus, since another region may be active first in the next contraction. The contraction of the first region results in a small rise of intrauterine pressure. This pressure rise increases tension on the entire wall of the uterus. Increased tension then stimulates mechanically sensitive ion channels, globally resulting in more frequent depolarization of syncytia. This leads to a second regional contraction, which is not limited to a region physically located adjacent to the originally active region. With two regions contracting, intrauterine pressure rises further, wall tension increases further, and the feed-forward process will continue until all or most regions are contracting simultaneously (Figure 1). The pauses between contractions are the result of a spectrum of electrical and metabolic processes that limit the duration of a contraction, and also set a minimum time between contractions, called the refractory period. The predictions of this model accord with the recordings from the array of superconducting quantum interference devices.

Figure 1.

Organizational structure for generating phasic rises of intrauterine pressure from myocytes.

Figure 1.

Organizational structure for generating phasic rises of intrauterine pressure from myocytes.

One final consideration for self-organization: Good experimental evidence exists that CAPs are more highly expressed following mechanical stimulation [18]. Thus, CAPs allow electrical activity, electrical activity causes contractions, self-organization of the uterus allows contractions to create pressure, and pressure allows greater expression of CAPs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mechanisms for symmetry reduction in the emergence of synchronized, coordinated contractions in labor.

| No. | Event | Necessary Component | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quiescent myocytes to electrical active myocytes | Ion channels | Electrical excitability |

| 2 | Isolated myocytes to syncytial organization | Cx43 | Electrical and metabolic sharing |

| 3 | Syncytial grouping to regions | Cx43 | Phase coupling of oscillators |

| 4 | Regional signaling to organ-level organization | Intrauterine pressure | Mechanotransduction |

The self-organizing process is critical. Without it, the contractions of the cells would not be synchronized in syncytia, syncytia would not be coordinated into regional contractions, regional contractions would not be coordinated into an organ-level contraction, intrauterine pressure would not rise optimally, the cervix would not dilate, and the baby would not be born. It seems clear that the emergence of synchronized uterine contractions from the quiescent pre-labor behavior is an energy-intensive, negentropic process marked by a reduction in symmetry at each step of self-organization. The transition from quiescence to active labor has much in common with other systems in which changes in certain control parameters lead to an unstable critical point from which a new phase emerges, typically exhibiting periodicity. Examples are plentiful, and include Rayleigh–Bénard convection, in which order and periodicity emerges spontaneously in a vessel of fluid heated from below [19], and the emergence of periodic gait patterns in quadrupeds [20,21]. By bringing together the recent work of a range of authors, it is now possible to interpret in a new way the mechanism whereby the uterine milieu is brought to a series of unstable critical points, and from which regular contractions emerge spontaneously.

Through its stepwise organization, our model shows how myocytes first transition to independent oscillators and end up generating coordinated organ-level contractions. A similar phenomenon has been described by Giuseppe Caglioti in the behavior of an audience at the end of the concert, where an initial response of exuberant applause gives way to synchronized, periodic clapping as the audience turns its attention to eliciting an encore from the performers [19]. In that example audience members initially respond as individuals, no doubt encouraged by the general enthusiasm of the audience, but essentially acting with a degree of indifference to those around them. As attention turns to eliciting an encore, individuals become more connected by attending more closely to the behavior of others in the audience. The subsequent emergence of synchronized clapping is a self-organized process that relies on connectivity between audience members. In the transition from pre-labor to labor, the expression of CAPs causes individual myocytes to shift from a state of relative indifference to their neighbors to a highly connected state, from which the relentless stimulus of intrauterine pressure drives a self-organizing process towards the emergence of synchronized contractions.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we present an alternate view to the long-held presumption that the synchronized behavior of the uterus is subject to a well-defined internal organization (as is found in the heart) that exists or was created prior to the onset of labor. While individual components such as ion channels and Cx43 are overexpressed prior to the onset of labor, in our model the sequential self-organization through cellular- and tissue-level functional units is the dominant mechanism for emergence of the organ-level synchronization necessary for human labor.

We suggest that the search for a uterine pacemaker has been unfruitful for the sole reason that it is non-existent. Rather, we assert that self-organization is the basis for uterine synchronization, resonating with Prigogine’s contention that:

“The maintenance of organization in nature is not—and cannot be—achieved by central management. Order can only be maintained by self-organization. Self-organizing systems allow adaptation to the prevailing environment, i.e., they react to changes in the environment with a thermodynamic response which makes the systems extraordinarily flexible and robust against perturbations from outside conditions.”[22]

Author Contributions

The hypothesis of self-organization in human labor was conceived and developed by R.S. and R.Y., and the concept was framed in terms of symmetry reduction by D.B. Details of uterine electrophysiology were provided by R.Y. and M.I., and the illustrations were produced by J.P., D.B., R.S. and R.Y wrote the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Depolarization results from an influx of anions across the membrane, initiated by mechanisms including the hyperpolarization-activated inward current and the low-threshold T-type calcium ion (Ca2+) currents. With increasing depolarization, sodium currents are activated, causing further rapid depolarization, which in turn activates high-threshold L-type Ca2+ currents that sustain the plateau phase of the action potential. Subsequently voltage- and calcium-activated potassium currents, and the deactivation of depolarizing currents, drive the membrane potential towards resting potential and terminate the action potential.

- Note: In this sequence, Ca2+ binds to Calmodulin, producing a complex that activates myosin light chains. This leads to phosphorylation of myosin light chains, which in turn enables interaction between myosin and actin heavy chains. It is this interaction between myosin and actin heavy chains that causes cell shortening [20]

- Butler, T.; Paul, J.; Europe-Finner, N.; Smith, R.; Chan, E. Role of serine-threonine phosphoprotein phosphatases in smooth muscle contractility. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C485–C504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, S.; Jones, K.; Kupittayanant, S.; Li, Y.; Matthew, A.; Monir-Bishty, E.; Noble, K.; Pierce, S.J.; Quenby, S.; Shmygol, A.V. Calcium signaling and uterine contractility. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2003, 10, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkington, H.C.; Tonta, M.A.; Brennecke, S.P.; Coleman, H.A. Contractile activity, membrane potential, and cytoplasmic calcium in human uterine smooth muscle in the third trimester of pregnancy and during labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 181, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.; Yeh, S.Y.; Schifrin, B.S.; Paul, R.H.; Hon, E.H. Quantitation of uterine activity in 100 primiparous patients. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1976, 124, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, R.C.; Barendse, P. Linking myometrial physiology to intrauterine pressure; how tissue-level contractions create uterine contractions of labor. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csapo, A. Progesterone “block”. Am. J. Anat. 1956, 98, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesiano, S.; Chan, E.-C.; Fitter, J.T.; Kwek, K.; Yeo, G.; Smith, R. Progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation in human parturition are coordinated by progesterone receptor A expression in the myometrium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 2924–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R. Parturition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Two forms of estrogen are produced during pregnancy-estriol, produced in the placenta from fetal steroid precursors, and estradiol, produced from precursors made in the maternal adrenal gland. While both estriol and estradiol act on estrogen receptors, in eqimolar concentrations they form heterodimers which block estrogenic actions. Late in pregnancy, the growth of the fetal adrenal causes the rate of increase in estriol production to outstrip that of estradiol production, causing estriol to become dominant over estradiol, and through the production of estriol homodimers the uterine environment becomes increasingly estrogenic. An extraordinary consequence of this is that, while in a healthy pregnancy it is the maturation of the fetus that stimulates the estrogenic signals that lead to the emergence of labor, in the event that the baby dies, maternal estrogen becomes the signal, ensuring that the mother is not left with a dead fetus in-utero [23].

- Sakai, N.; Tabb, T.; Garfield, R.E. Studies of connexin 43 and cell-to-cell coupling in cultured human uterine smooth muscle. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 167, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S.M.; Daniel, E.E.; Garfield, R.E. Improved electrical coupling in uterine smooth muscle is associated with increased numbers of gap junctions at parturition. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982, 80, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfield, R.E.; Blennerhassett, M.G.; Miller, S.M. Control of myometrial contractility: Role and regulation of gap junctions. Oxf. Rev. Reprod. Biol. 1988, 10, 463–490. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.C.; Goloman, G. Phasic oscillations of extracellular potassium (K(o)) in pregnant rat myometrium. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramon, C.; Preissl, H.; Murphy, P.; Wilson, J.D.; Lowery, C.; Eswaran, H. Synchronization analysis of the uterine magnetic activity during contractions. Biomed. Eng. Online 2005, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csapo, A. The diagnostic significance of the intrauterine pressure. II. Clinical considerations and trials. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1970, 25, 515–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibb, W.; Challis, J.R. Mechanisms of term and preterm birth. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2002, 24, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caglioti, G. The Dynamics of Ambiguity; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Golubitsky, M.; Stewart, I.; Buono, P.-L.; Collins, J.J. Symmetry in locomotor central pattern generators and animal gaits. Nature 1999, 401, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, I.; Golubitsky, M. Fearful Symmetry: Is God a Geometer? Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 2011; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I. The End of Certainty: Time, Chaos, and the New Laws of Nature; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed, M.; Castano, E.; Notides, A.C.; Sasson, S. Molecular and kinetic basis for the mixed agonist/antagonist activity of estriol. Mol. Endocrinol. Baltim. Md. 1997, 11, 1868–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).