A Probabilistic Framework for Forecasting Cryptographic Security Under Quantum and Classical Threats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work and Comparative Analysis

| Model/Framework | Time | Stochastic | Valuation | Quantum | Simulatable | Lifecycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIST Lifecycle/PQC Guidance [4,5] | No | No | No | Partial | No | Yes |

| Attack Trees (Schneier) [19] | No | Yes (implicit) | No | No | No | Yes |

| FAIR Risk Model [21] | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Bayesian/Markov Security Models [13] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Partial | No |

| Trigeorgis (Real Options) [16] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Pecen (Practitioner IP valuation; personal communication) [22] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| This Work (Proposed) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Research Status and Open Issues

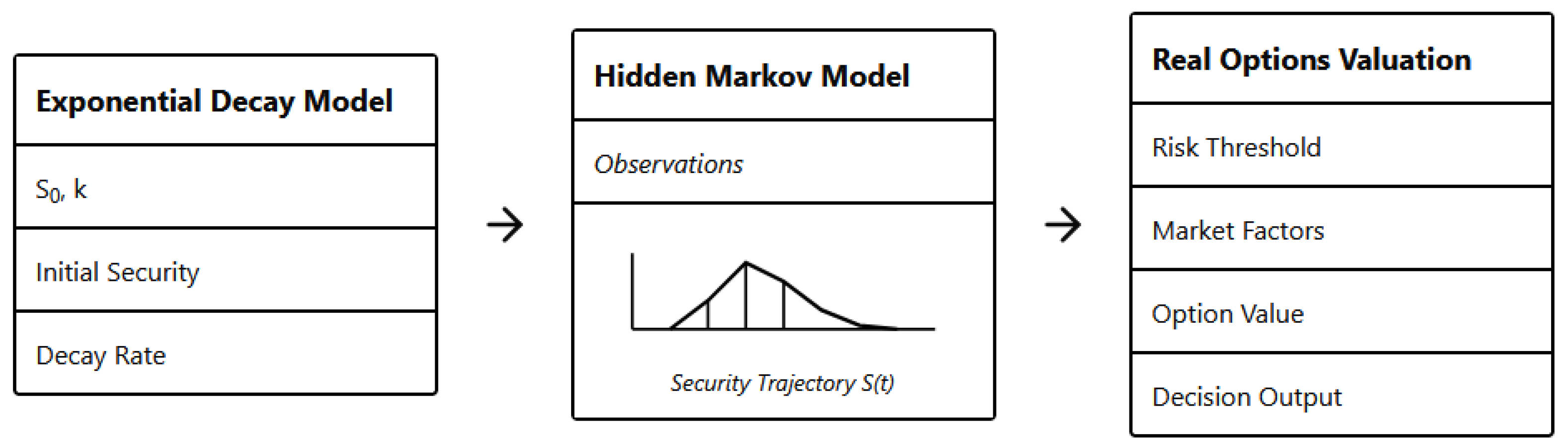

3. Model Components

3.1. Exponential Security Decay Model

3.2. Discrete-State Security Transition Modeling via Hidden Markov Processes

3.3. Real Options Approach to Cryptographic Security Valuation (After Pecen)

- 1.

- and be multiplicative security shift factors;

- 2.

- be the volatility of cryptographic risk (e.g., measured from historical compromise timelines);

- 3.

- be the risk-neutral transition probability.

4. Notation and Definitions

5. Model Integration Architecture

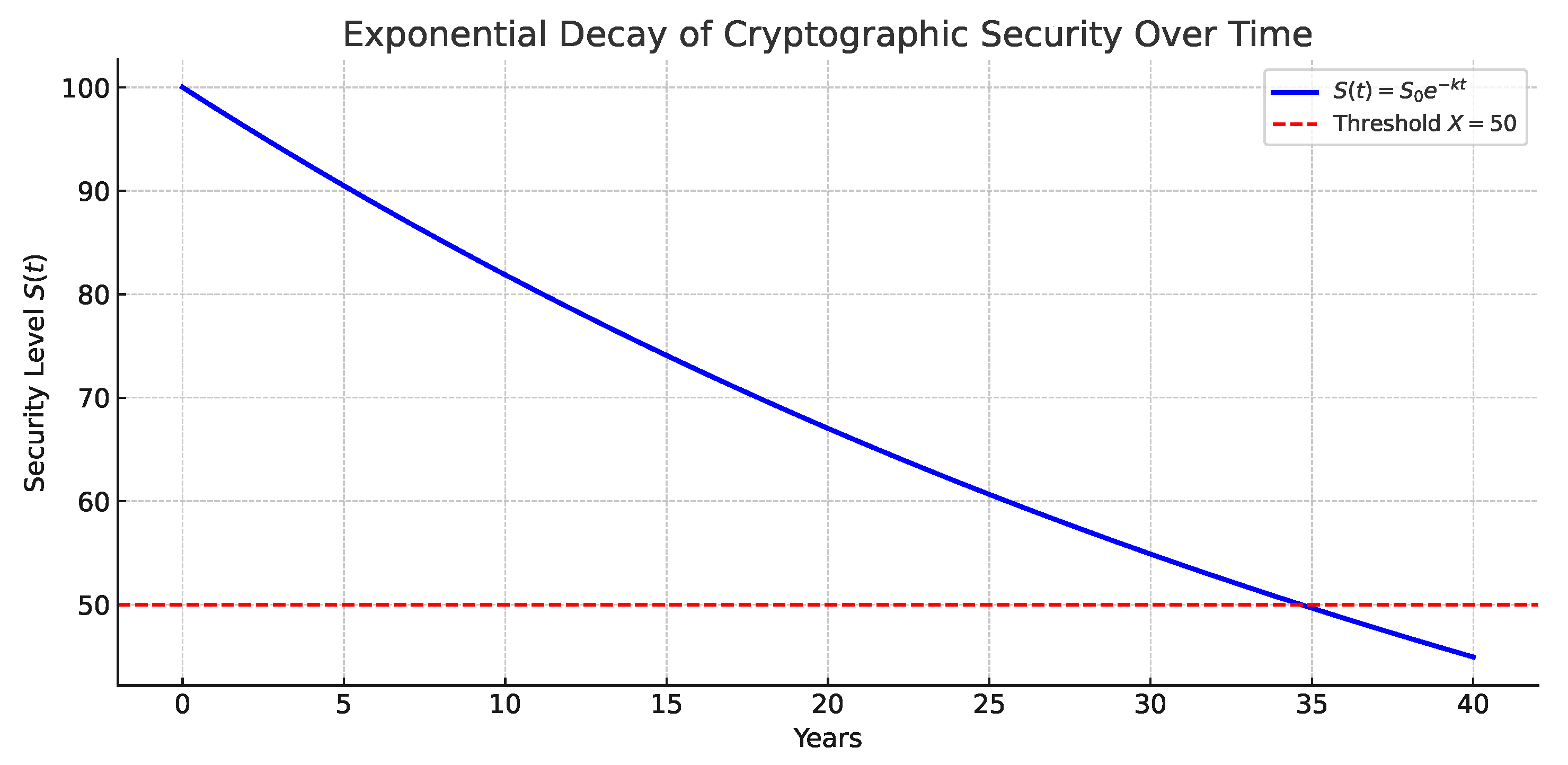

5.1. Stage I: Continuous Security Degradation (Exponential Decay)

5.2. Stage II: Probabilistic State Transition (Hidden Markov Model)

5.3. Stage III: Security Option Valuation (Binomial Model)

- 1.

- The latest continuous security level represents the underlying value of cryptographic strength in the lattice.

- 2.

- The policy-defined minimum acceptable security threshold (the “strike”) is taken from the risk-tolerance matrix R for asset class a.

- 3.

- The volatility and effective discount rate are modulated by the HMM output, for example, by increasing as the probability of being in the At Risk state grows, or by raising when adversarial activity is believed to be accelerating.

Quantitative Derivation of from Posterior HMM Outputs

5.4. Functional Coupling Summary

5.5. Practical Implementation Workflow

- 1.

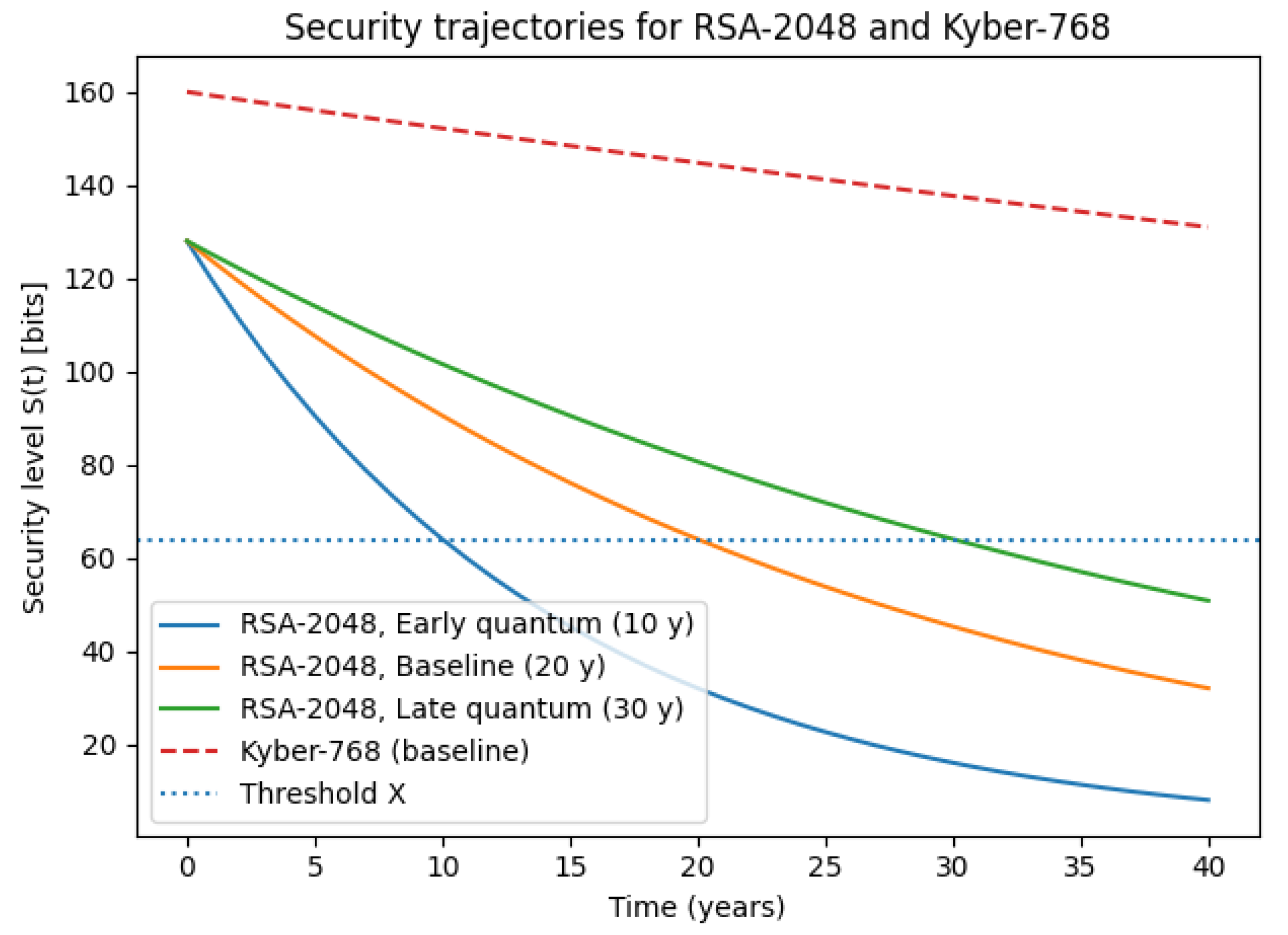

- Portfolio and parameter initialization. The practitioner first compiles a portfolio of cryptographic mechanisms used across asset classes (e.g., RSA-2048 for TLS key exchange, AES-256-GCM for bulk encryption, and post-quantum candidates such as Kyber-768 or Dilithium-3). For each cipher–asset pair , the initial security level is expressed in “bits of (classical and quantum) security,” together with performance and deployment metadata (latency constraints, key-size limits, presence of hardware accelerators) [20]. Scenario-specific decay constants are then specified for classical-only, quantum-enabled, and aggressive-quantum threat models.

- 2.

- Running Stage I and constructing observation sequences (output of Stage I → Stage II). Stage I is evaluated over a discrete horizon to obtain trajectories for all . These trajectories are sampled at yearly or quarterly resolution to form observation sequences . At this point, the artifact produced by Stage I is a matrix of security levels over time whose rows are cipher–asset pairs and columns are time steps; this matrix becomes the emission data for the HMM.

- 3.

- Risk-tolerance matrix and HMM calibration (Stage II implementation). The organization specifies a risk-tolerance matrix R with rows indexed by asset class and columns by latent state . Entry , for example, encodes the minimum acceptable security level for asset class a to be considered Moderately Secure. Each element of is mapped to a provisional state label using R, producing symbol sequences that are fed into a Hidden Markov Model. Using standard libraries, the practitioner estimates the transition matrix T and obtains posterior state probabilities , which summarize when each cipher–asset pair is likely to become At Risk under the specified quantum scenarios.

- 4.

- Mapping to option parameters and valuation (Stage III implementation). For each cipher–asset pair, Stage III takes as input the latest security level from Stage I and the risk metrics from Stage II. The current underlying in the binomial lattice is set to ; the strike is taken from the risk-tolerance matrix as the minimum acceptable security for asset class a; and the volatility is calibrated from the variability of over the planning horizon. Migration costs—including the expected performance overhead of PQC candidates (e.g., increased ciphertext size or handshake latency) and re-engineering effort—are folded into the effective discount rate . Running the binomial option model then yields an option value for migrating from a legacy cipher to a selected PQC algorithm.

- 5.

- Decision outputs and iteration. The final artifacts of the implementation are (i) a ranked list of cipher–asset pairs by their option values , (ii) recommended migration windows and “latest safe migration dates” for each pair, and (iii) sensitivity analyses under different quantum-threat scenarios. In practice, the workflow is executed periodically as new cryptanalytic results, hardware benchmarks, or PQC performance measurements become available, updating , R, T, and the resulting migration roadmap without changing the core structure of the framework.

6. Simulation Results

6.1. Exponential Security Decay

6.2. Hidden Markov Transitions

- 1.

- : Highly Secure;

- 2.

- : Moderately Secure;

- 3.

- : At Risk.

6.3. Binomial Option Valuation

- 1.

- (discount rate);

- 2.

- (volatility);

- 3.

- (minimum security threshold);

- 4.

- years;

- 5.

- (binomial steps).

Sensitivity to the Policy Threshold X and the Latest Safe Migration Date

6.4. Demonstration: Migration from RSA-2048 to Kyber-768

6.4.1. Security Decay Under Quantum-Arrival Scenarios

6.4.2. State Transitions for the Baseline Scenario

6.4.3. Option-Style Valuation of Migration Incentives (Stage III)

7. Limitations and Future Work

- 1.

- The decay rate k is constant over time, though it may vary in real-world conditions.

- 2.

- Hidden Markov transitions are based solely on thresholds and do not yet incorporate noisy emissions or adversarial signals.

- 3.

- The option pricing model assumes a fixed time horizon and deterministic policy threshold X.

- 4.

- The framework forecasts when security may cross policy thresholds, but does not yet explicitly model crypto-agility constraints (e.g., migration lead time and deployment feasibility) [23].

- 1.

- Calibration using real-world cryptanalytic event timelines (e.g., factoring breakthroughs, side-channel disclosures) and operational response timelines (e.g., disclosure-to-patch delays for high-impact vulnerabilities), which directly affect practical exposure windows [37].

- 2.

- Monte Carlo uncertainty propagation through the full pipeline. Rather than a single deterministic run, we sample uncertain parameters (e.g., , HMM parameters , and valuation parameters ) from fitted/posterior distributions and execute Stage I → Stage II → Stage III per sample. Aggregating results yields confidence intervals for and for the “latest safe migration date”, and supports stress-testing against rare-but-plausible cryptanalytic shocks.

- 3.

- Incorporating migration lead time and deployment feasibility into Stage III so that recommended migration windows reflect operational constraints [23].

- 4.

- Integration with standard post-quantum algorithm migration plans and cryptographic lifecycle guidelines.To our knowledge, no existing framework integrates time-dependent security decay, probabilistic transitions, and financial valuation for cryptographic lifecycle forecasting. This model bridges a key gap between theoretical cryptography and actionable cybersecurity risk management.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ASIC | Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| AQT | Applied Quantum Technologies |

| CDF | Cumulative Distribution Function |

| CSF | Cybersecurity Framework |

| CX | Controlled-X gate |

| ECDSA | Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm |

| FAIR | Factor Analysis of Information Risk |

| GCM | Galois/Counter Mode |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| JVG | Jesse–Victor–Gharabaghi |

| PQC | Post-Quantum Cryptography |

| QFT | Quantum Fourier Transform |

| QNTT | Quantum Number-Theoretic Transform |

| RSA | Rivest–Shamir–Adleman |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

References

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (US). Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard; Technical Report NIST FIPS 203; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (US). Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard; Technical Report NIST FIPS 204; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (US). Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard; Technical Report NIST FIPS 205; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards; NIST Interagency Report (NISTIR) 8547; Initial Public Draft; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Preparing for Post-Quantum Cryptography; Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA): Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alagic, G.; Bros, M.; Ciadoux, P.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Dang, T.; Kelsey, J.; Lichtinger, J.; Liu, Y.K.; Miller, C.; et al. Status Report on the Fourth Round of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process; Technical Report NIST IR 8545; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, E.; Chen, L.; Regenscheid, A.; Moody, D.; Newhouse, W.; Kent, K.; Barker, W.; Cooper, D.; Souppaya, M.; Housley, R.; et al. Considerations for Achieving Crypto Agility: Strategies and Practices; Technical Report 39; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0; Technical Report NIST CSWP 29; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Recommendation for Key Management: Part 1—General; NIST Special Publication 800-57 Part 1 Rev. 5; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaroch, M. Real Options Models for Proactive Uncertainty-Reducing Mitigations and Applications in Cybersecurity Investment Decision Making. Inf. Syst. Res. 2018, 29, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M.; Piani, M. Quantum Threat Timeline Report 2024; Industry Report; Annual Expert Survey on the Likelihood and Timing of Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computers (e.g., Ability to Break RSA-2048 Within Defined Windows); Global Risk Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada; evolutionQ Inc.: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner, L.R. A Tutorial on Hidden Markov Models and Selected Applications in Speech Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1989, 77, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, W. Regime switching model estimation: Spectral clustering hidden Markov model. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 303, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Yang, H.; Pi, J.; Wang, C. Network virus propagation and security situation awareness based on Hidden Markov Model. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigeorgis, L. Real Options: Managerial Flexibility and Strategy in Resource Allocation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, J. Real Options Analysis: Tools and Techniques for Valuing Strategic Investments and Decisions; Wiley Finance: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, G. Real Options in Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneier, B. Attack Trees. Schneier on Security (Archive). 1999. Available online: https://www.schneier.com/academic/archives/1999/12/attack_trees.html (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Kerschbaum, F.; Ochoa, M. Adaptive and Application-Aware Selection of Cryptographic Primitives. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 8–12 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. An Introduction to Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR); Whitepaper/Industry Report; Risk Management Insight LLC: Cordova, TN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pecen, M. (EigenQ, Inc., Austin, TX, USA). Personal Communication, 4 September 2025.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Crypto Agility; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W. Applied Life Data Analysis; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Meeker, W.Q.; Escobar, L.A.; Pascal, P. Statistical Methods for Reliability Data, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Black, F.; Scholes, M. The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities. J. Political Econ. 1973, 81, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, R.R. Moore’s law: Past, present and future. IEEE Spectr. 1997, 34, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neven, H. Computing Takes a Quantum Leap Forward. The Keyword (Google Blog). 23 October 2019. Available online: https://blog.google/innovation-and-ai/products/computing-takes-quantum-leap-forward/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for Quantum Computation: Discrete Logarithms and Factoring. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS), Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–22 November 1994; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, L.K. A Fast Quantum Mechanical Algorithm for Database Search. arXiv 1996, arXiv:quant-ph/9605043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees; Wadsworth International Group: Belmont, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, Z.; Jordan, M.I. Factorial Hidden Markov Models. Mach. Learn. 1997, 29, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Furman, S.; Hardy, N.; Ellis, M.; Back, G.; Hong, Y.; Cameron, K. A Detailed Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Influence of Hardware Artifacts on SPEC Integer Benchmark Performance. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.16690v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Griensven Thé, J.; Oliveira Santos, V.; Gharabaghi, B. A Novel Quantum Circuit for Integer Factorization: Evaluation via Simulation and Real Quantum Hardware. Comput. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumani, Y. Patching zero-day vulnerabilities: An empirical analysis. J. Cybersecur. 2021, 7, tyab023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Effective security trajectory, initial level, and decay constant. | |

| Latent HMM state at time t and transition probabilities. | |

| Asset-dependent minimum acceptable security threshold (“strike”). | |

| Posterior probability of latent state s for cipher–asset pair . | |

| Option-style value used to compare retain/migrate decisions over time. | |

| Effective discount rate and volatility parameter in the lattice model. | |

| Binomial up/down factors, risk-neutral probability, and number of steps. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rosas-Bustos, J.R.; Pecen, M.; Van Griensven Thé, J.; Fraser, R.A.; Said, N.; Ratto Valderrama, S.; Thanos, A. A Probabilistic Framework for Forecasting Cryptographic Security Under Quantum and Classical Threats. Symmetry 2026, 18, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020297

Rosas-Bustos JR, Pecen M, Van Griensven Thé J, Fraser RA, Said N, Ratto Valderrama S, Thanos A. A Probabilistic Framework for Forecasting Cryptographic Security Under Quantum and Classical Threats. Symmetry. 2026; 18(2):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020297

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosas-Bustos, José R., Mark Pecen, Jesse Van Griensven Thé, Roydon Andrew Fraser, Nadeem Said, Sebastian Ratto Valderrama, and Andy Thanos. 2026. "A Probabilistic Framework for Forecasting Cryptographic Security Under Quantum and Classical Threats" Symmetry 18, no. 2: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020297

APA StyleRosas-Bustos, J. R., Pecen, M., Van Griensven Thé, J., Fraser, R. A., Said, N., Ratto Valderrama, S., & Thanos, A. (2026). A Probabilistic Framework for Forecasting Cryptographic Security Under Quantum and Classical Threats. Symmetry, 18(2), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020297