16. Introduction

Despite the global energy transition, coal continues to occupy a pivotal position in the primary energy landscape as of 2024 [

1]. In conventional longwall mining, the “gob-side entry driving” method remains prevalent, which necessitates the excavation of two roadways for a single working face and the retention of a wide protective coal pillar, typically ranging from 15 to 30 m in width [

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, this traditional layout is plagued by significant drawbacks. Statistical data indicate that this practice results in the permanent loss of approximately 10–15% of the total coal resources in a mining area, alongside issues of stress concentration within the pillar and excessive excavation volumes [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. To mitigate these issues, gob-side entry retaining (GER) technology has been extensively adopted [

12,

13]. By constructing an artificial roadside wall to replace the protective coal pillar, GER allows the roadway to be retained for the subsequent working face. This approach not only maximizes the coal recovery rate but also significantly reduces the excavation workload, aligning with the principles of sustainable “green mining” [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Recent investigations have further expanded the applicability of GER in complex geological settings, focusing on the optimization of backfill materials and roof control techniques to ensure long-term stability [

18,

19,

20].

From a structural mechanics perspective, conventional layouts maintain a relative bilateral symmetry in boundary confinement. In stark contrast, GER introduces a fundamental structural asymmetry: one side of the retained entry is supported by the rigid solid coal, while the other is confined by the collapsing goaf and an artificial roadside wall. This symmetry-breaking geometry and stiffness distribution fundamentally alter the stress redistribution and deformation characteristics, particularly within the advance pressure zone. Studies show that the roof subsidence in the advance segment can reach 300–800 mm, accounting for over 40% of the total roadway deformation throughout the mining cycle. This poses a severe threat to the stability of the roadside support system. Extensive research has been conducted to manage this asymmetry through various roadside backfill materials. Zhang [

21] and Liu [

22] studied the use of wood stacks and dense supports to enhance roadside support, which proved effective in restraining surrounding-rock deformation. Guo [

23] used high water slag-cement filling material for gob-side filling and conducted a preliminary study on the mechanism and the determination of mechanical parameters. Zhou [

24,

25] took advantage of the natural phenomenon of the roof falling rocks in the goaf of the inclined seam, and a temporary support means was applied to stop the roof falling rocks in the goaf at the upper sidewall of the goaf side gateway. Then the shotcreting, grouting and other measures were applied to consolidate the roof falling rocks and to form the stable backfilled masses with the falling rocks as the main backfilling material of the goaf side gateway. Deng [

26] and Tang [

27] analyzed the feasibility of roadside packing with ordinary concrete for GER and designed a rational and economical support system. Li [

28] and Bai [

29] studied a technique of backfilling the goaf-side entry retaining for the next sublevel and established a mechanical model of the backfilling beside the GRE for the next sublevel by using the paste backfilling material. Wang [

30] used high-water materials for roadside filling and formed the principle and method of “one-passing, four synergies, five in one” coordinated control of GER with dual-roadway. Wang [

31] examined deviatoric-stress evolution in FFC-supported GER and developed a combined support scheme featuring a reinforced thin FFC wall, double-row strong props, and asymmetrically arranged, high-preload anchor cables in the roof and solid coal.

More recently, flexible-formwork concrete (FFC) has gained prominence due to its adaptability, rapid construction speed, and superior sealing performance [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Nevertheless, a critical engineering challenge remains unresolved: FFC does not achieve its design strength immediately after casting. This time-dependent strength gain creates a “weak window” where the roadside wall provides insufficient confinement. The existing literature has largely focused on the final strength of the backfill or the stability of the entry behind the working face. There is a notable lack of research elucidating the advance pressure mechanism driven by the coupled effect of FFC curing delay and structural asymmetry.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to elucidate the advance pressure evolution mechanism in FFC-based GER and to develop a symmetry-enhancing control strategy. Taking the N1215 panel of the Ningtiaota Coal Mine as a case study, we employed field investigations and 3D numerical modeling to analyze the stress environment. A quantitative evaluation system was established to optimize the advance support parameters. Finally, a “hydraulic prop-anchor cable” coupled support technology was proposed and validated. The findings provide a theoretical basis for ensuring roadway stability in asymmetric mining layouts.

2. Engineering Situations

2.1. Geological Parameters of Working Face

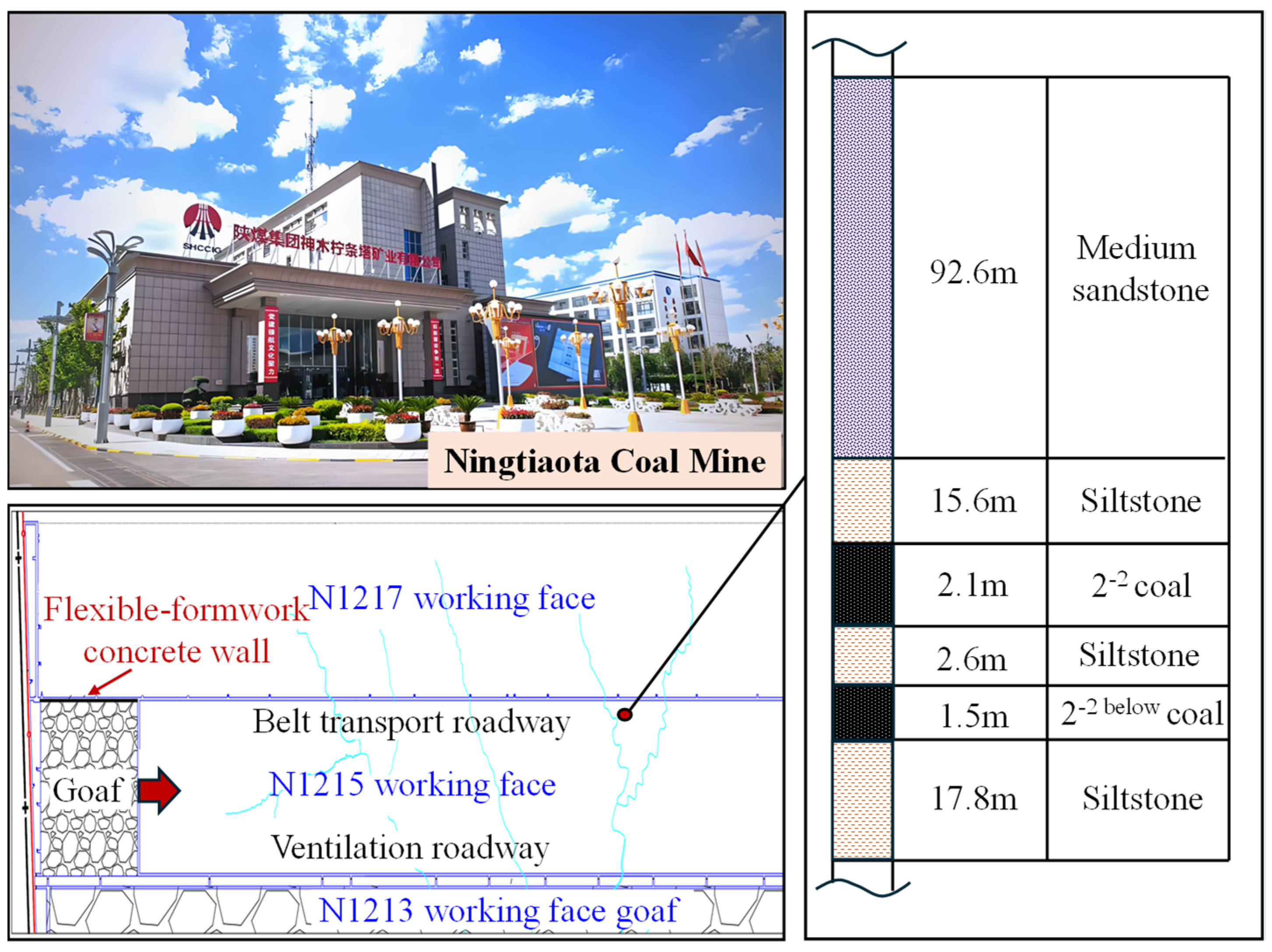

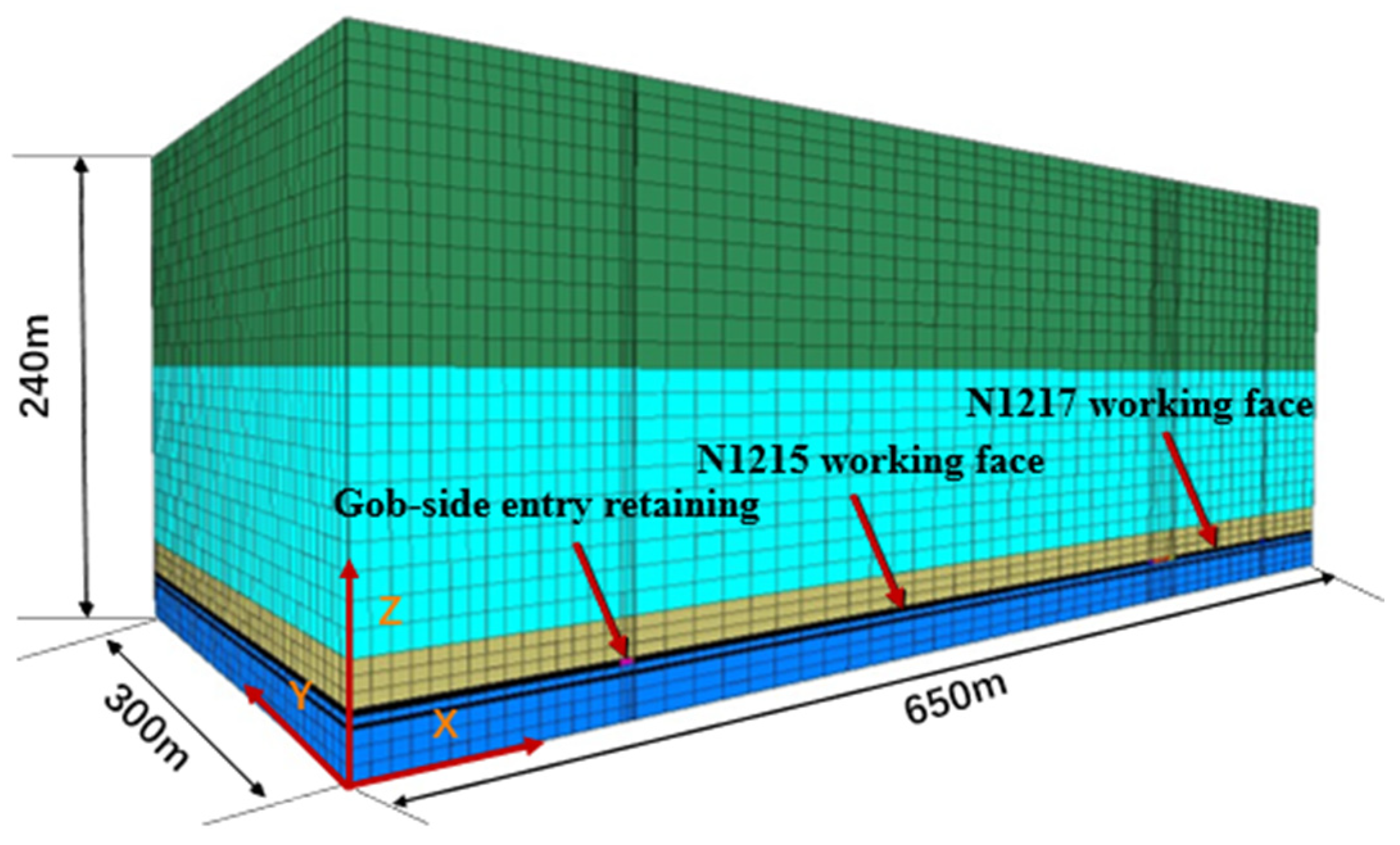

The N1215 working face is located in the west of the coal production system of 2

−2 in the north wing of the mine field, with a burial depth of 130 m~220 m. The N1215 working face extends 2981.4 m along strike and 344.5 m along dip. The coal seam averages 2.1 m in thickness, and the dip angle is less than 2°. The geometric arrangement of the working face and its lithological composition are summarized in

Figure 1.

2.2. The Parameters of GER

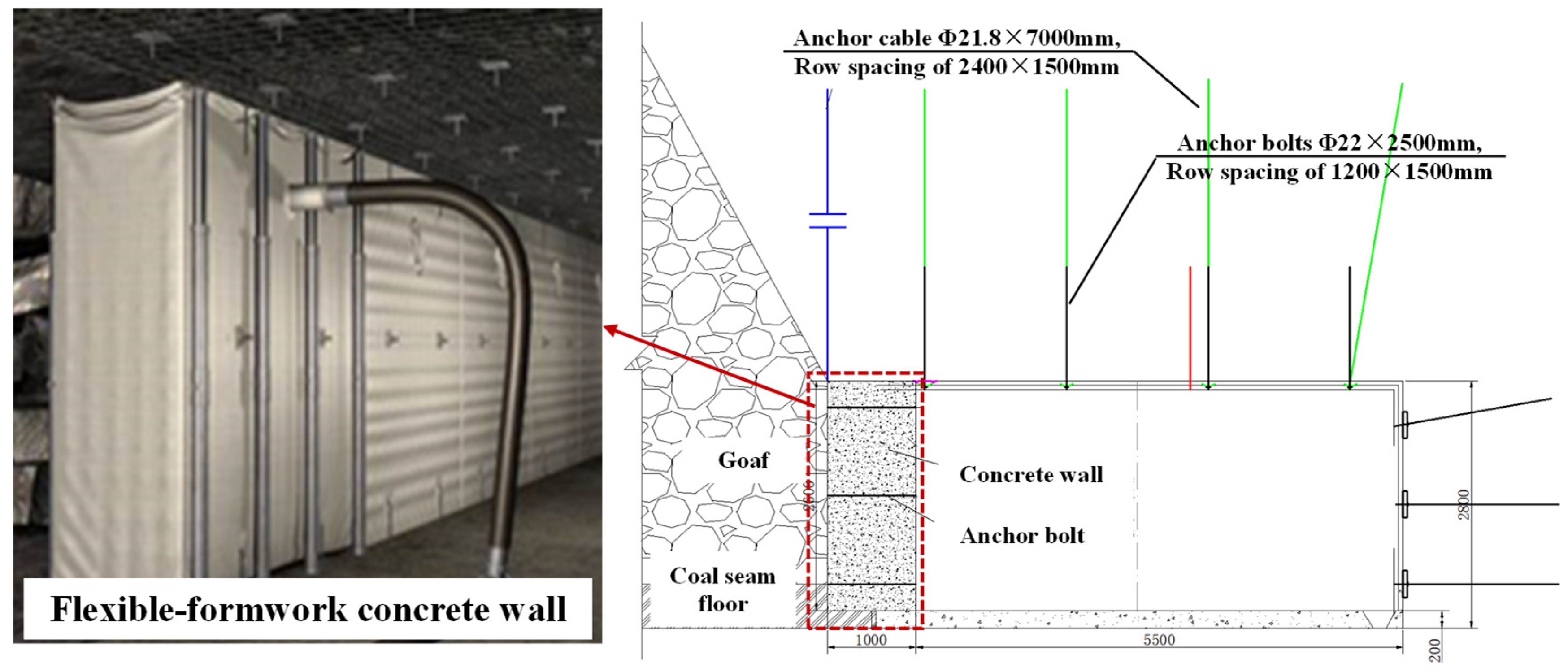

The FFC continuous wall is used for the gob-side support in the roadway retaining segment of the belt transport roadway, as shown in

Figure 2. The roadside support parameters are as follows: the GER width is 5500 mm, the FFC wall width is 1000 mm, and concrete strength grade is C30. The roof is supported by anchor net cable + W-steel belt. The roof anchor bolts are supported by Φ22 × 2500 mm left-handed threaded steel anchors with a row spacing of 1200 × 1500 mm. The roof anchor cables are supported by Φ21.8 × 7000 mm prestressed-steel-strand anchor cables with a row spacing of 2400 × 1500 mm. The anchor cable spacing on the mining side near the working face is 1200 mm, and the BH280 type W-steel belt is used for reinforcement.

2.3. Damage Analysis of the Field

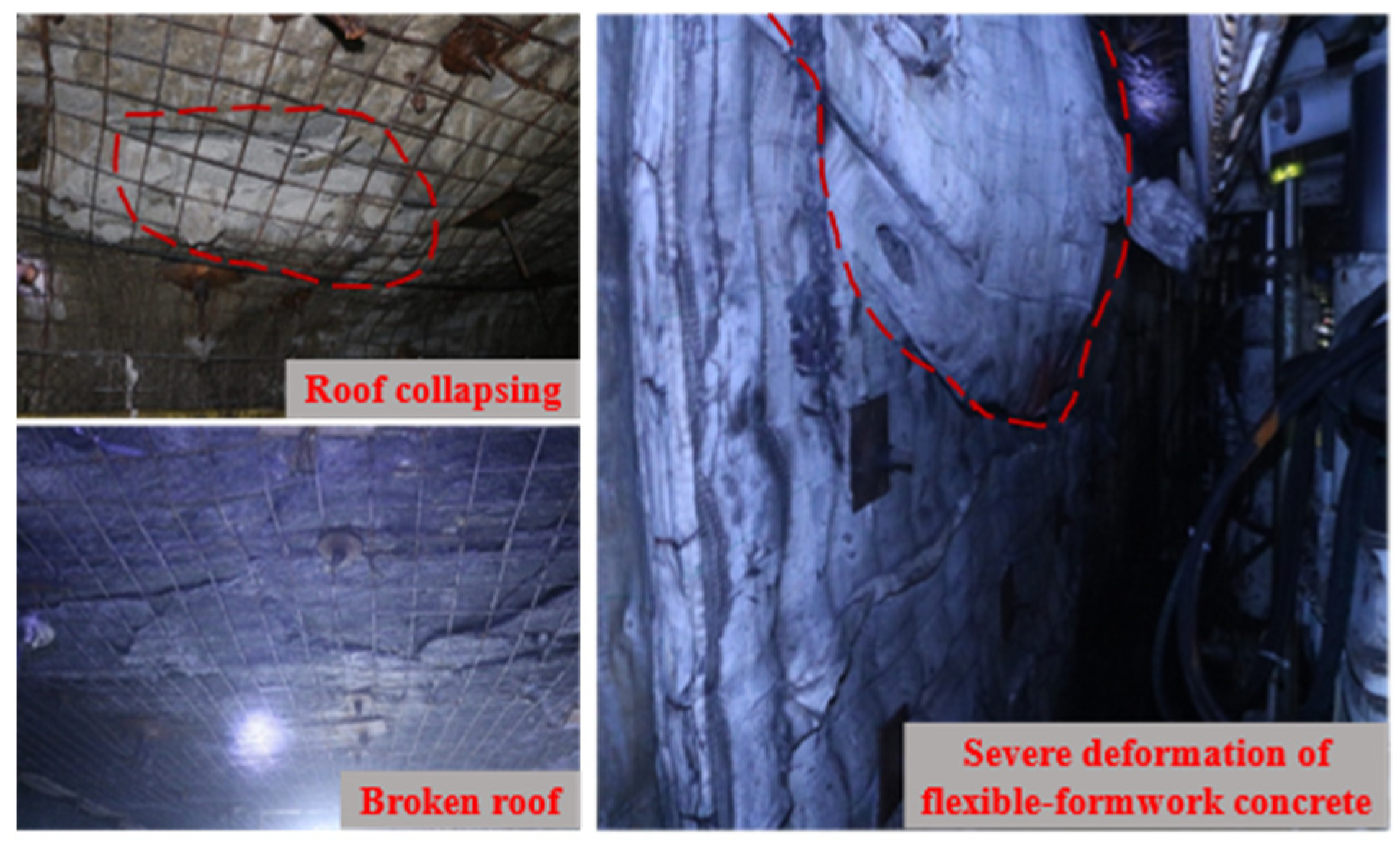

Under the influence of advance pressure and excavation disturbance, the roof of the advance segment of the GER is seriously broken. It should be noted that no effective maintenance or reinforcement measures were performed on the roadway roof prior to this investigation. The field observation is shown in

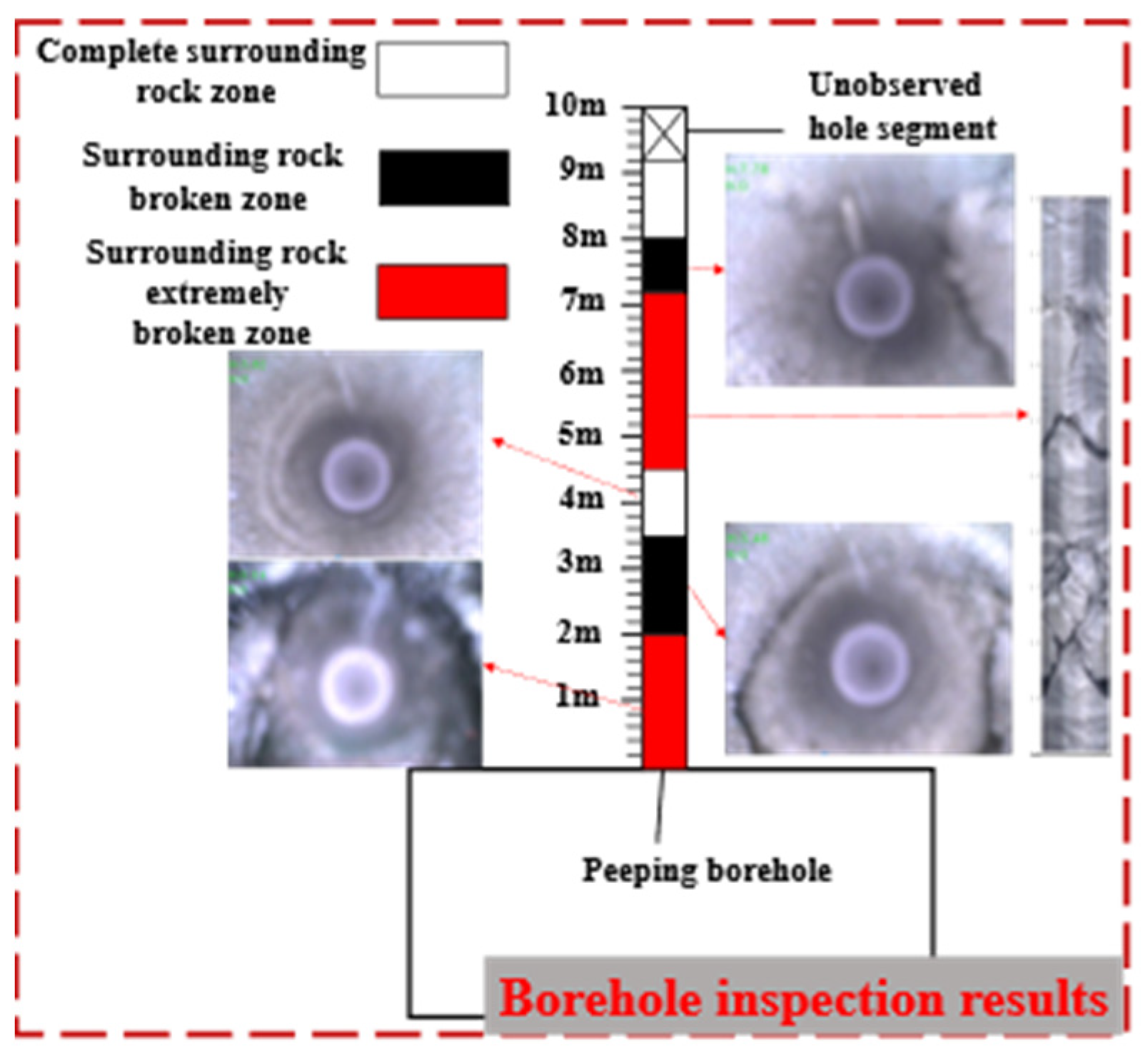

Figure 3. The surrounding rock in the borehole is detected by borehole cameras. According to the detection results, the roof’s surrounding rock is divided into the complete zone, the broken zone and the extremely broken zone. The specific partition and peeping results are presented in

Figure 4.

(1) Since the FFC wall cannot reach the rated strength in a short time, it takes a certain period of time to form effective support. Part of the FFC is destroyed before the effective support formed, and the advance support is not carried out on the field in time. Therefore, it had a serious impact on the appearance of the advance pressure of roadway, causing the roof of the advance segment to be broken.

(2) The roadway roof shows severe loosening and progressive degradation, accompanied by a marked reduction in surrounding-rock strength. Within the peeped 9 m borehole range, there are 7 m lengths in the surrounding-rock broken zone and the surrounding-rock extremely broken zone. Due to the roof broken, the supporting form of anchor bolt (cable) cannot play the supporting role, and the loosening zone expands, which in turn aggravates roadway deformation in the advance segment.

In order to ensure safe and efficient mine production, the appearance mechanism of advance pressure of GER with FFC was explored urgently. Then, the advance-strengthening support method was established, and the comprehensive evaluation and optimization system for the whole process of GER was formed.

3. Numerical Analysis of GER

To clarify the advance-pressure mechanism of GER with FFC, a full-process numerical investigation was conducted for a fully mechanized longwall face, using the N1215 panel as the case study.

3.1. Model Setup

Numerical modelling was conducted for the N1215 panel using a model consistent with in situ conditions. The numerical simulation is strictly governed by the fundamental principles of elastoplastic mechanics and the finite difference method (FDM). The model domain measures 650 m × 300 m × 240 m (L × W × H), as illustrated in

Figure 5. To accurately capture the failure characteristics of the strata, the Mohr–Coulomb yield criterion is adopted as the constitutive model for the coal and rock mass. This model mathematically defines the plastic yield envelope based on the cohesion and internal friction angle, effectively simulating both shear slippage and tensile failure behaviors. In contrast, the flexible-formwork concrete (FFC) wall and support components are modeled using the Linear Elastic constitutive model, where the stress–strain relationship follows Hooke’s Law. A fixed constraint was applied at the model bottom, the side boundaries were restricted to prevent horizontal displacement, and the initial in situ stress field was imposed to match site conditions. After the model ground stress balanced, it reached 6.6 MPa, which is consistent with the field in situ stress monitoring data.

Based on the geological report and laboratory tests, the physical and mechanical parameters assigned to the numerical model are listed in

Table 1.

3.2. Evaluation Index

The roof stress increase rate

δR quantitative evaluation index is established as the percentage increase in roof stress relative to the initial in situ stress during face advance and entry retention. The corresponding expression is given as follows:

where

δR is the roof stress increase rate. Higher δR values correspond to stronger roof stress concentration.

Smax is the roof stress, MPa.

Sini is the original rock stress at the roadway, MPa.

3.3. Result Analysis

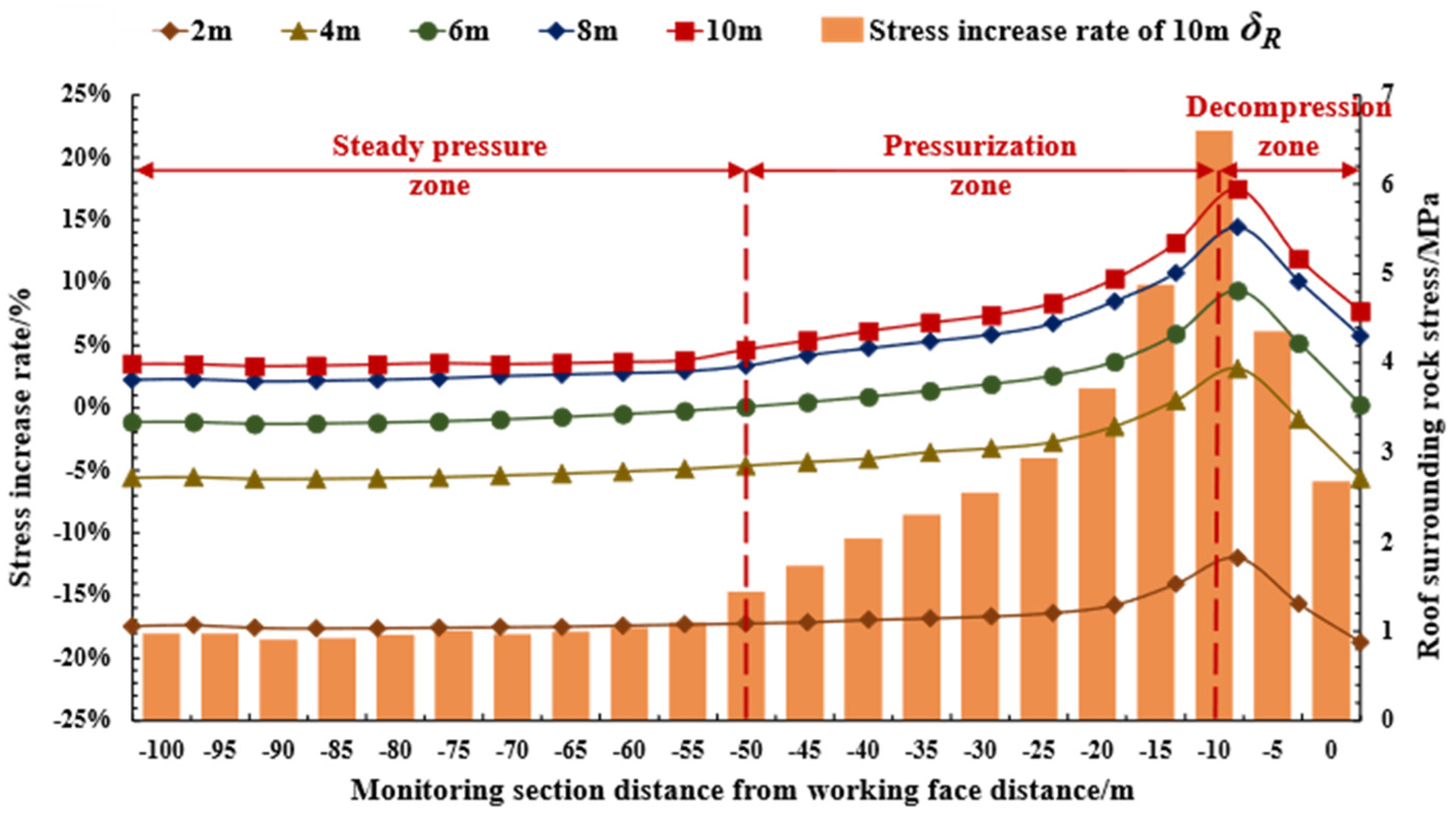

Without advance support, the stress response ahead of face was analyzed to determine the advance-pressure influence range and to assess the need for advance support. The changes of roof stress at depths of 2 m, 4 m, 6 m, 8 m and 10 m of are analyzed. The variation of roof stress in the advance segment without advance support is shown in

Figure 6.

The results in

Figure 6 show the following:

(1) The law of advance pressure shows obvious zoning characteristics, which may be partitioned into steady pressure zone, pressurization zone and decompression zone. In steady pressure zone (−100 m~−50 m), the roof stress has no obvious variation. In pressurization zone (−50 m~−10 m), the roof stress gradually rises and reaches the peak value. In decompression zone (−10 m~0 m), the roof stress shows a gradually decreasing trend.

(2) During face mining, roof stress in the advance zone rises initially and then declines. The roof stress begins to rise significantly when it is −50 m. The roof stress increase rate of 10 m deep from the roof is −14.68% at −50 m, and the roof stress increase rate of 10 m deep from the roof reaches a peak value of 22.17% at −10 m. The roof stress increase rate increased by 36.85% during the entire roof stress increase stage.

In conclusion, the range from −50 m to 0 m is the zone where the advance pressure appears. The advance support design within this range is beneficial for improving roadway stability. To ensure safe mining, the research on the advance support design method was studied urgently.

4. Numerical Analysis of Advance Support Design

To ensure the safe mining, the rational design of advance support for GER with FFC is carried out, and roadway support parameters are evaluated and optimized. The numerical test research of the whole mining process for different advance support schemes of a fully mechanized mining working face is carried out. With the hydraulic-prop–anchor-cable coupling considered, the evolution of deformation and stress in the roadway for varying advance-support ranges, different advance hydraulic prop spacing, and different anchor cable spacing are compared and analyzed.

4.1. Schematic Design

Numerical test comparison schemes for the different advance support designs include scheme A (different advance support range), scheme B (different advance hydraulic prop spacing), and scheme C (different anchor cable spacing). Scheme A, B and C all take the field roadway section size, ground stress, surrounding rock strength, etc., as invariants, and numerical tests are carried out with the advance support range, advance hydraulic prop spacing and anchor cable spacing as variables in turn.

(1) Scheme A

The roadway deformation and stress evolution laws under different advance support ranges are compared and analyzed in this scheme. Taking the advance support range as a variable, numbered as A

i, where

I = 1~5, the corresponding advance support ranges are 10 m, 20 m, 30 m, 40 m, and 50 m, as shown in

Table 2.

(2) Scheme B

The roadway deformation and stress evolution laws under different advance hydraulic prop spacing are compared and analyzed in this scheme. Taking the advance hydraulic prop spacing as a variable, numbered as B

j, where

j = 1~4, the corresponding advance hydraulic prop spacings are 1.0 m, 1.5 m, 2.0 m, and 2.5 m, as shown in

Table 3.

(3) Scheme C

The roadway deformation and stress evolution laws under different anchor cable spacing are compared and analyzed in this scheme. Taking the anchor cable spacing as a variable, numbered as C

q, where

q = 1~5, the corresponding anchor cable spacings are 1.0 m, 1.2 m, 1.5 m, 2.0 m, and 2.5 m, as shown in

Table 4.

4.2. Quantitative Evaluation Indices

To quantitatively compare the stress–deformation responses of the roadway surrounding rock across different support schemes, the increase rate of side abutment pressure δSij and deformation control rate of surrounding rocks ηDij were established:

(1) The increase rate of side abutment pressure

δSij, which quantifies the relative increase in side abutment pressure with respect to the initial in situ stress during face advance and entry retention, is given as follows:

where

δSij is the increase rate of side abutment pressure. Higher δSij values correspond to stronger roof stress concentration. Here, I is A~C, representing the three designed schemes. J is the sub-scheme of each scheme, A. C type scheme j = 1~5; B type scheme j = 1~4.

Sijmax is the side abutment pressure peak value in the ij scheme, MPa.

Sini is the original rock stress at the roadway, MPa.

(2) The deformation control rate of surrounding rocks

ηDij is defined as the percentage reduction in maximum roof–floor convergence after roadway excavation for a given advance-support scheme relative to the case without advance support. The corresponding expression is given as follows:

where

ηDij is the deformation control rate. Higher ηDij values correspond to better surrounding-rock stability control.

Dw is the maximum roof–floor convergence in a no-advance-support case.

Dij is the maximum roof–floor convergence under the ij scheme.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Support Schemes

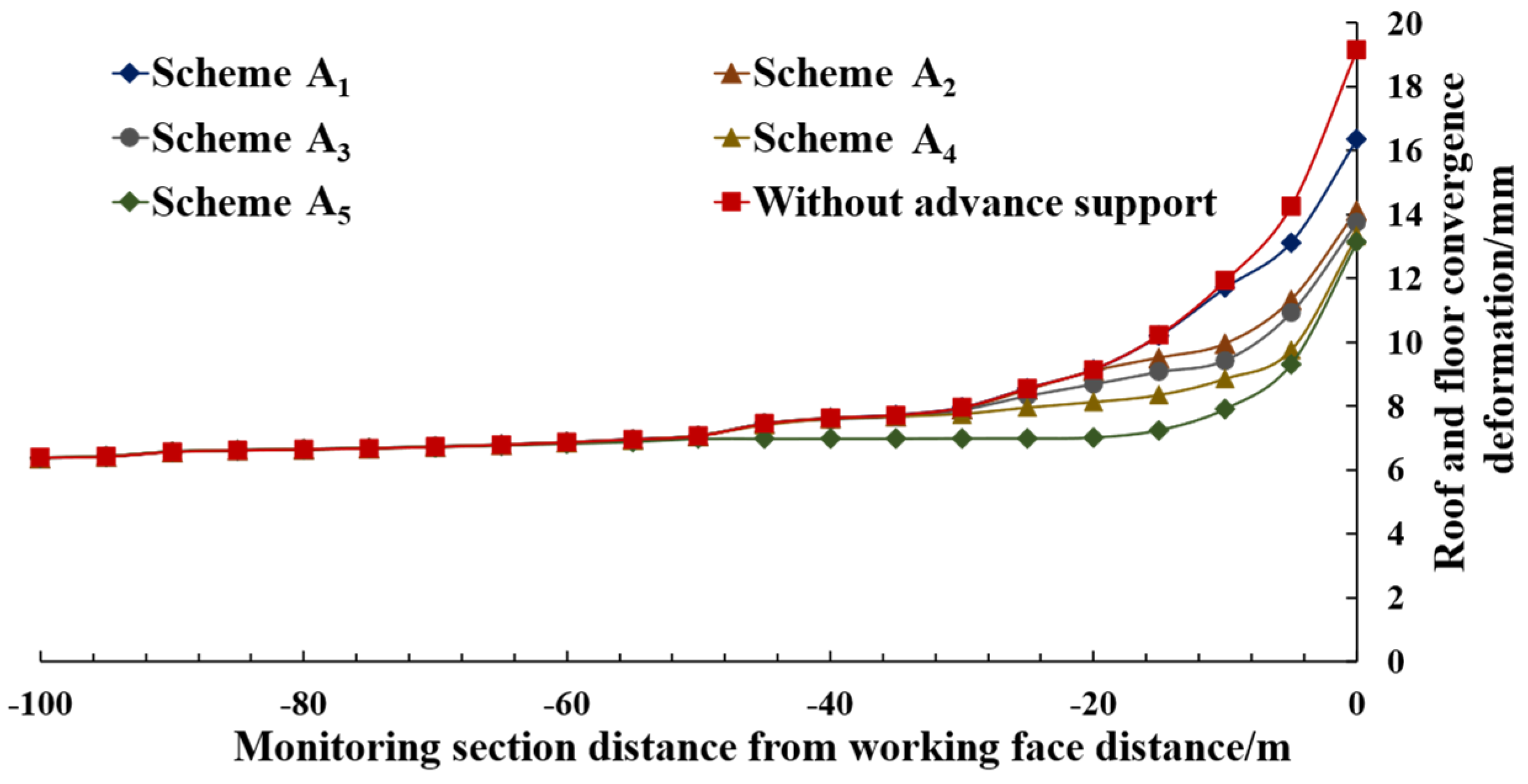

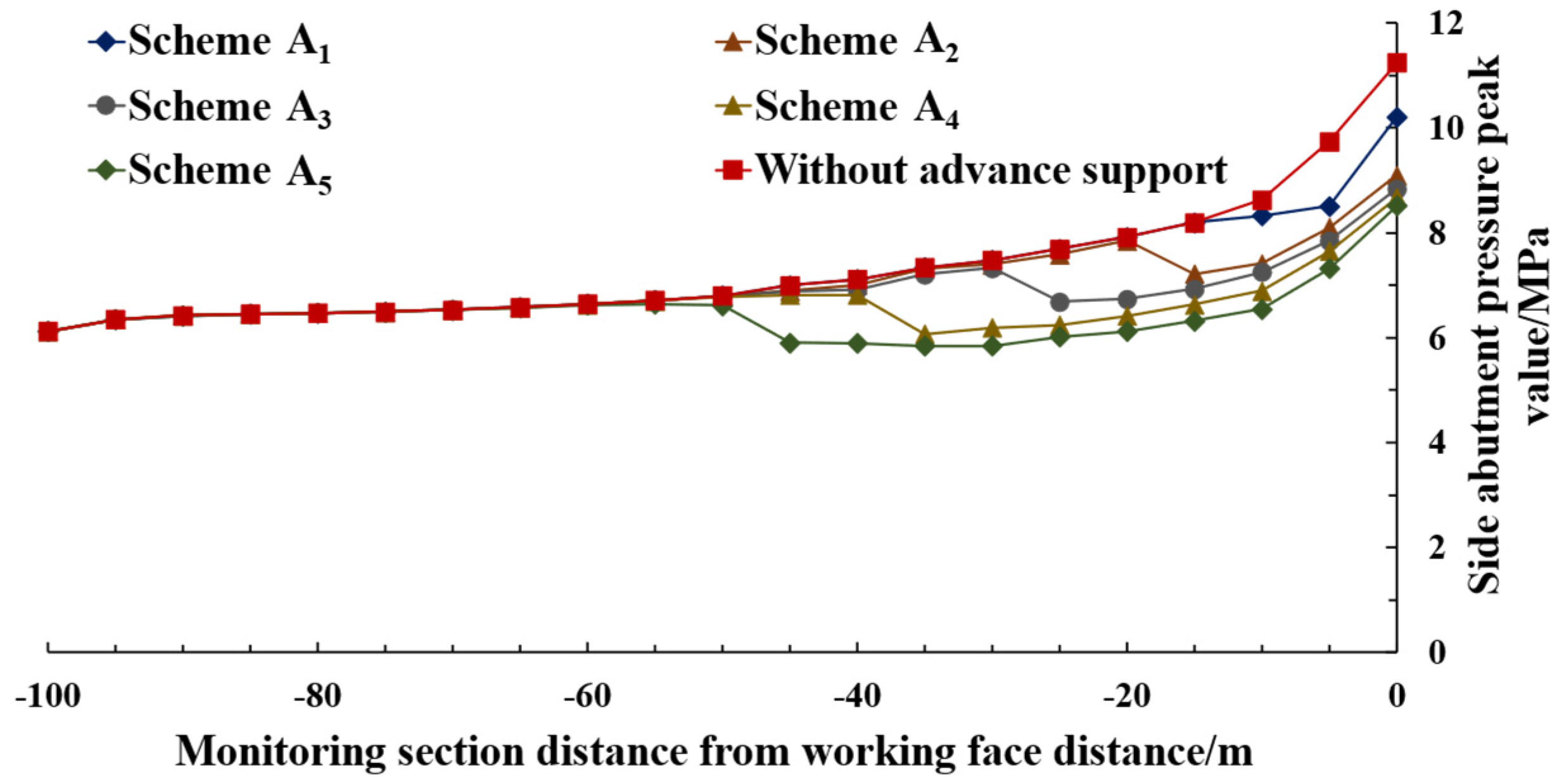

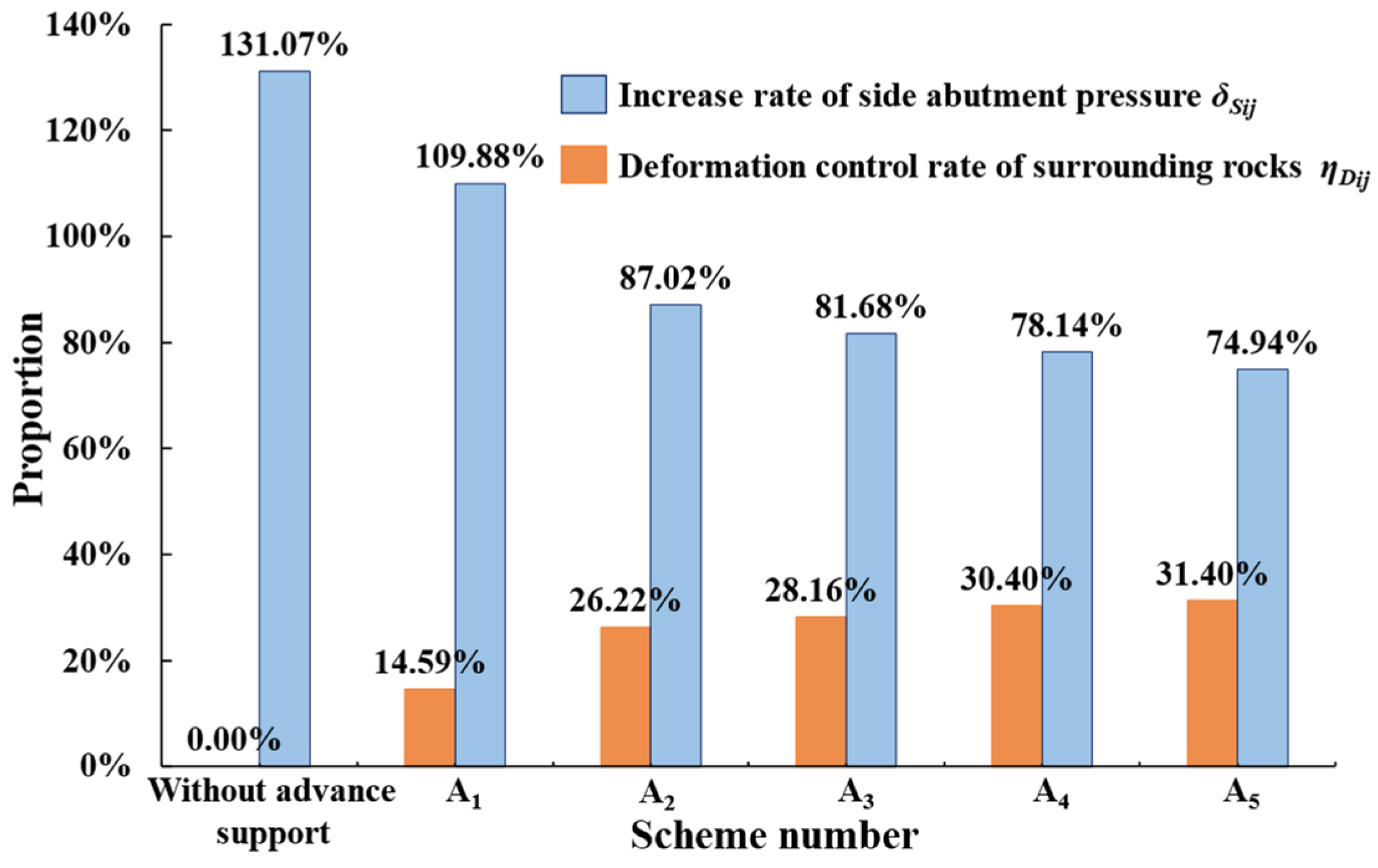

4.3.1. Result Analysis of Scheme A

This type of scheme (A

1~A

5) is compared and analyzed with the advance support range as a variable. The change curve of roof–floor convergence is plotted in

Figure 7. The evolution of the peak side abutment pressure is plotted in

Figure 8. The quantitative evaluation indexes of different advance support ranges are shown in

Figure 9.

(1) Deformation Control Efficiency: As the advance support range extends from 10 m to 50 m, the peak roof–floor convergence gradually decreases from 19.15 mm to 13.12 mm, demonstrating a significant restraint on roadway deformation compared to the non-supported condition. The deformation control rates for schemes A1~A5 are calculated as 14.59%, 26.22%, 28.16%, 30.40%, and 31.40%, respectively. Notably, a distinct inflection point is observed at the 20 m range. When the support range increases from 10 m to 20 m, the deformation control rate surges by 11.63%. However, extending the range further from 20 m to 30 m yields only a marginal increase of 1.94%. This sharp decline in marginal benefit indicates that a 20 m support range is sufficient to cover the primary zone of severe deformation.

(2) Stress Concentration Mitigation: A similar trend is observed in the stress evolution. With the expansion of the support range, the peak side abutment pressure decreases from 11.25 MPa to 8.51 MPa, indicating effective relief of stress concentration. The increase rate of side abutment pressure drops from 131.07% (without advance support) to 109.88%, 87.02%, 81.68%, 78.14%, and 74.94% for schemes A

1~A

5, respectively (as shown in

Figure 9). Consistent with the deformation data, the reduction in stress concentration slows down significantly once the support range exceeds 20 m. Consequently, based on the dual criteria of deformation control and stress relief, 20 m is determined as the optimal advance support range.

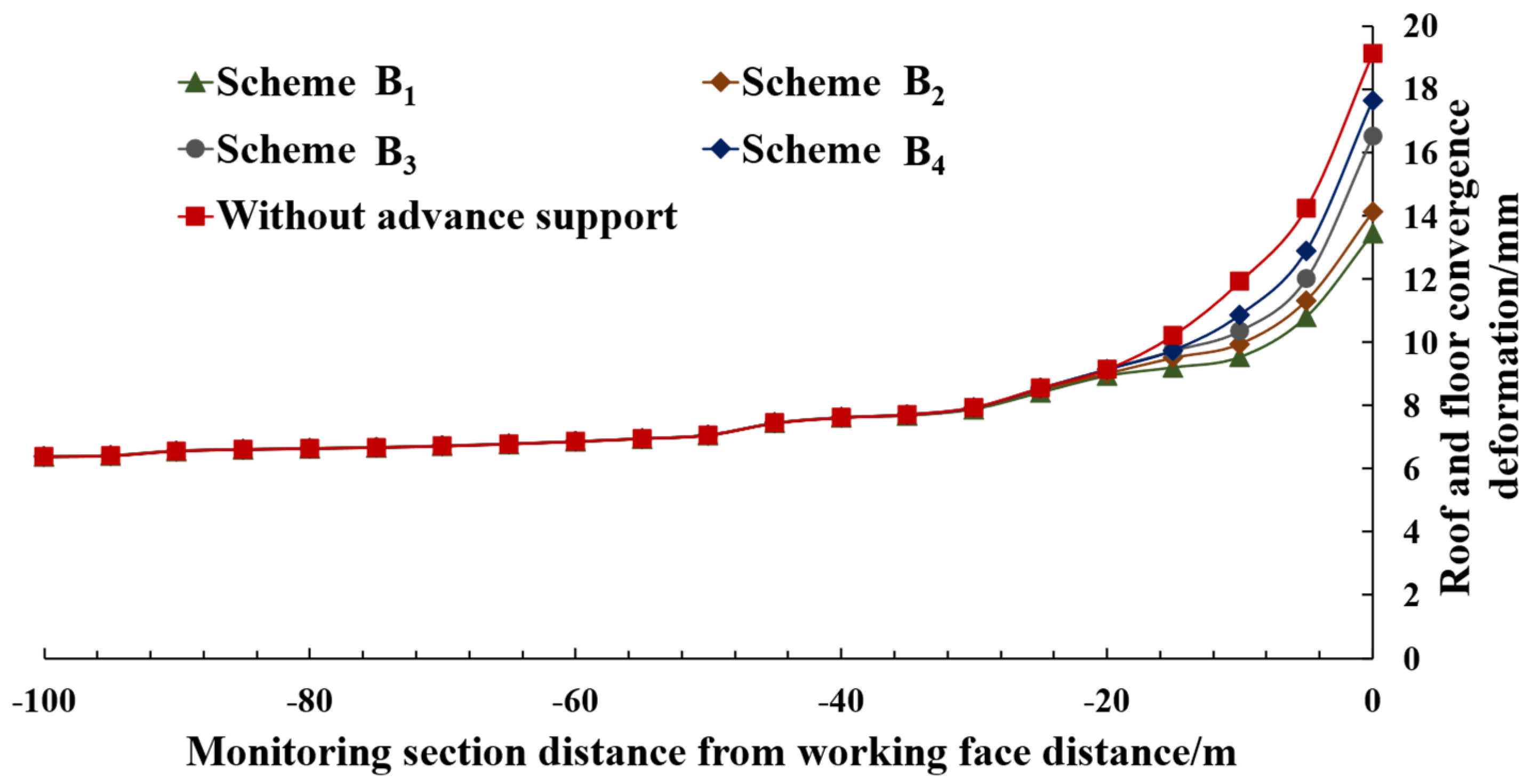

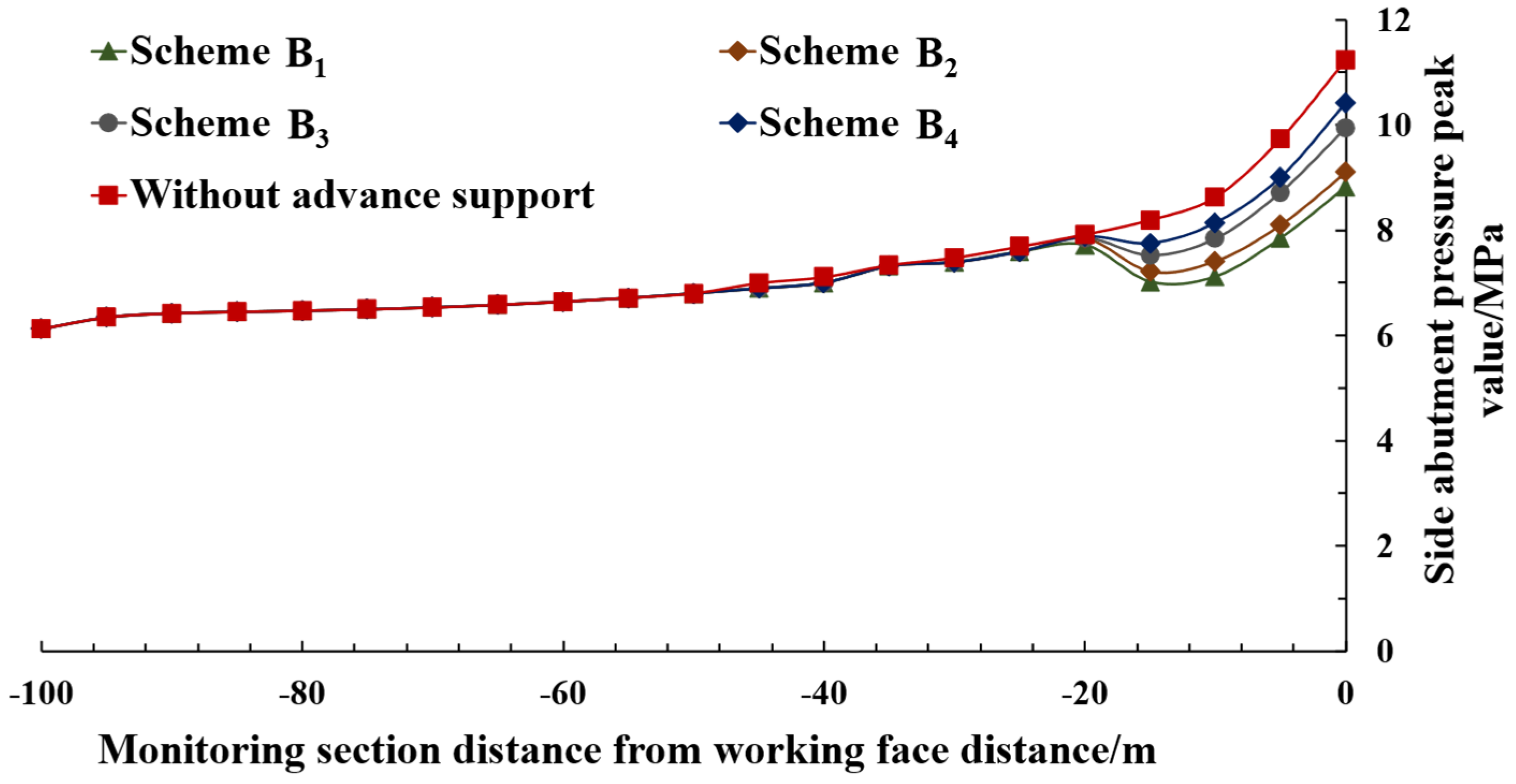

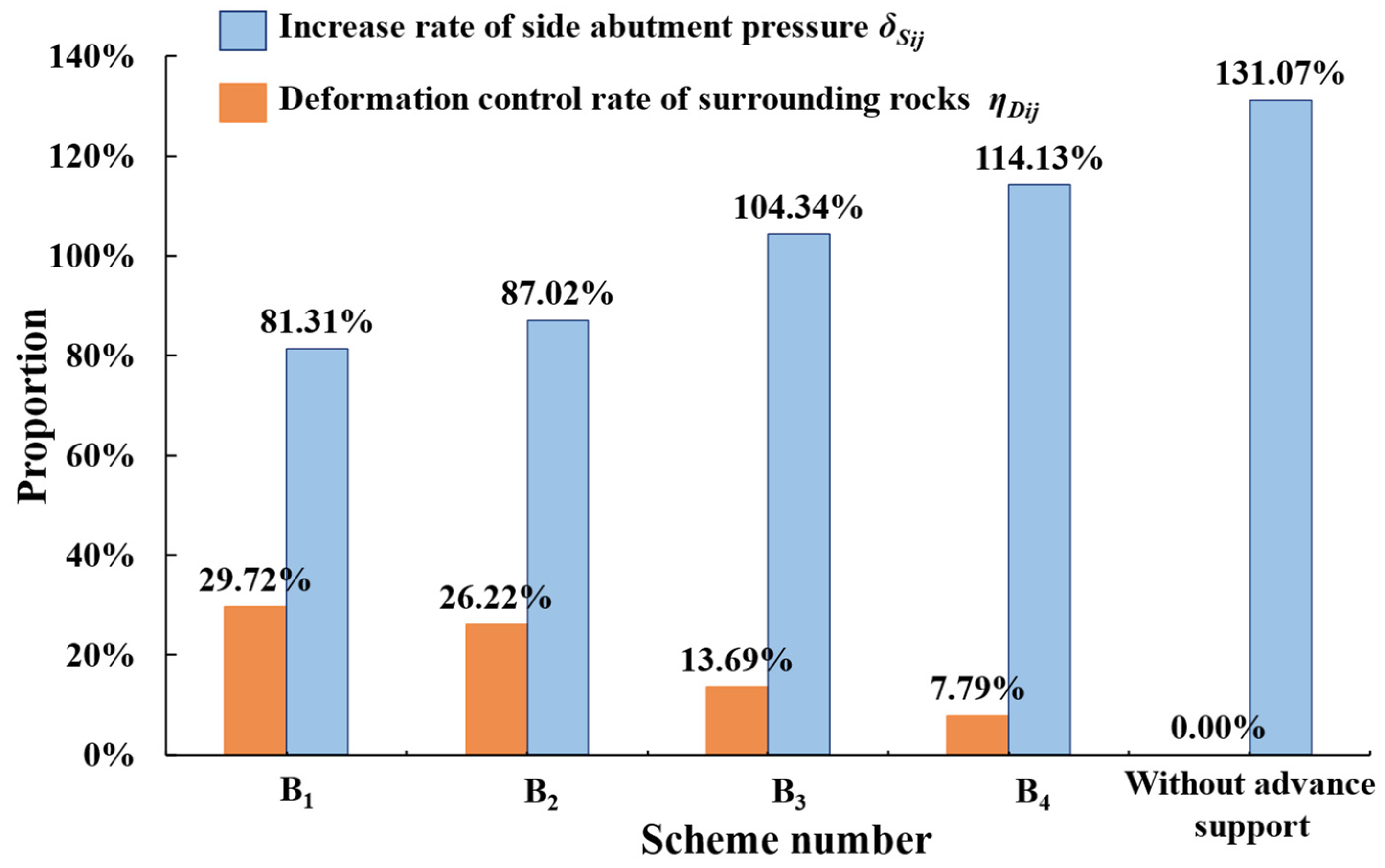

4.3.2. Result Analysis of Scheme B

This type of scheme (B

1~B

4) is compared and analyzed with the advance hydraulic prop spacing as a variable. The change curve of roof–floor convergence is plotted in

Figure 10. The evolution of the peak side abutment pressure is plotted in

Figure 11. The quantitative evaluation indexes of different advance hydraulic prop spacing are shown in

Figure 12.

(1) Deformation Control Efficiency: The densification of hydraulic props plays a crucial role in restraining roof subsidence. As shown in

Figure 10, increasing the prop spacing leads to a gradual increase in the maximum roof–floor convergence from 13.46 mm to 17.65 mm. In terms of control efficiency,

Figure 12 indicates that the deformation control rates for schemes B

1~B

4 are 29.72%, 26.22%, 13.69%, and 7.79%, respectively. A critical threshold is observed at the 1.5 m spacing mark. When the spacing is reduced from 2.0 m to 1.5 m, the deformation control rate improves significantly by 12.53%. In contrast, further reducing the spacing from 1.5 m to 1.0 m yields a marginal gain of only 3.5%. This diminishing return suggests that an excessively dense arrangement provides limited additional stability benefits while potentially hindering mining operations.

(2) Stress Concentration Mitigation: The evolution of side abutment pressure follows a similar pattern. With the decrease in hydraulic prop spacing, the peak side abutment pressure drops from 10.42 MPa to 8.82 MPa, confirming that the intensified support effectively shares the load and alleviates stress concentration. Quantitatively, the increase rate of side abutment pressure decreases from the baseline of 131.07% (without advance support) to 114.13%, 104.34%, 87.02%, and 81.31% for schemes B1–B4, respectively. Consistent with the deformation analysis, the reduction in the stress increase rate becomes less pronounced when the spacing is less than 1.5 m. Therefore, considering both the control effectiveness and operational feasibility, 1.5 m is identified as the optimal hydraulic prop spacing.

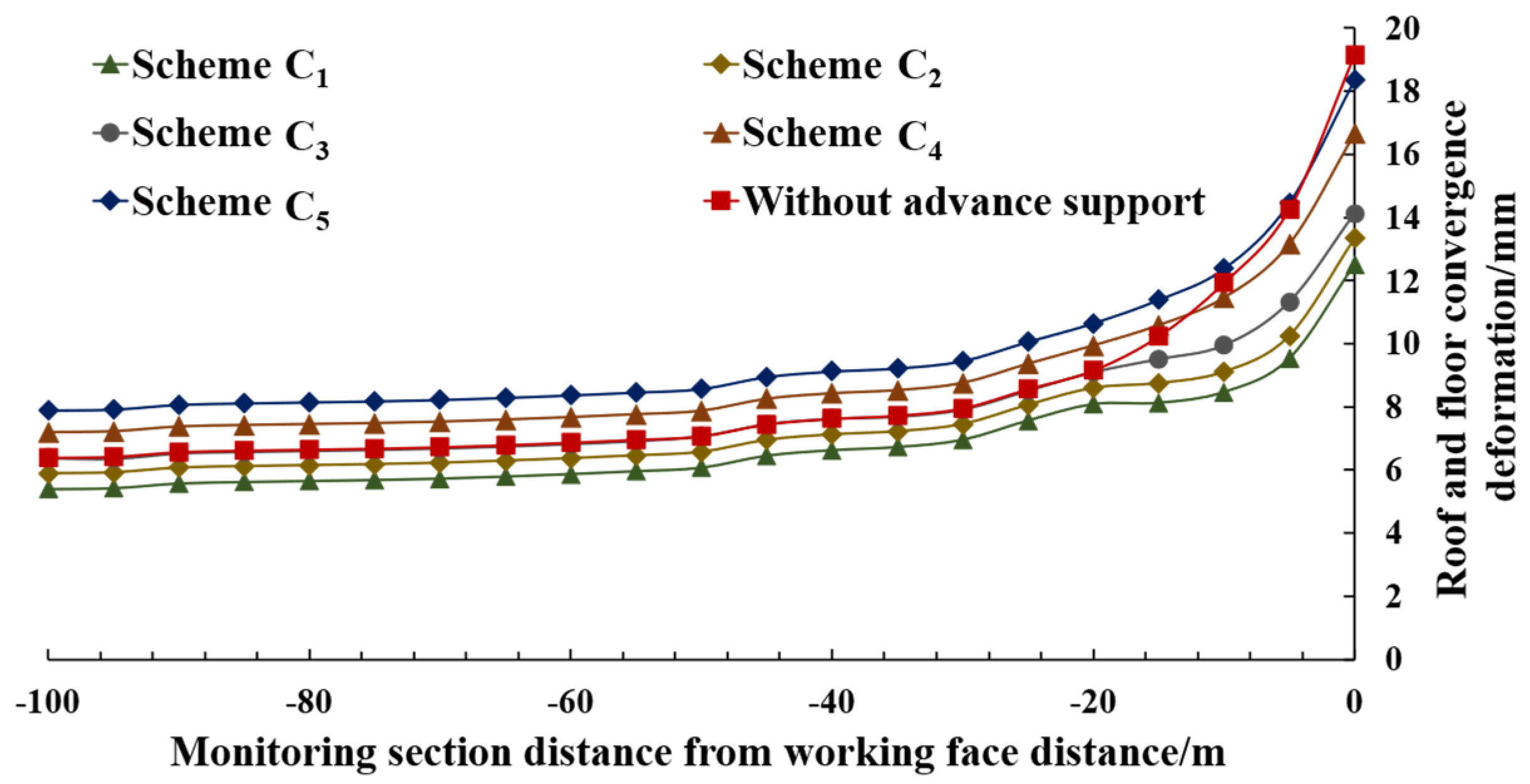

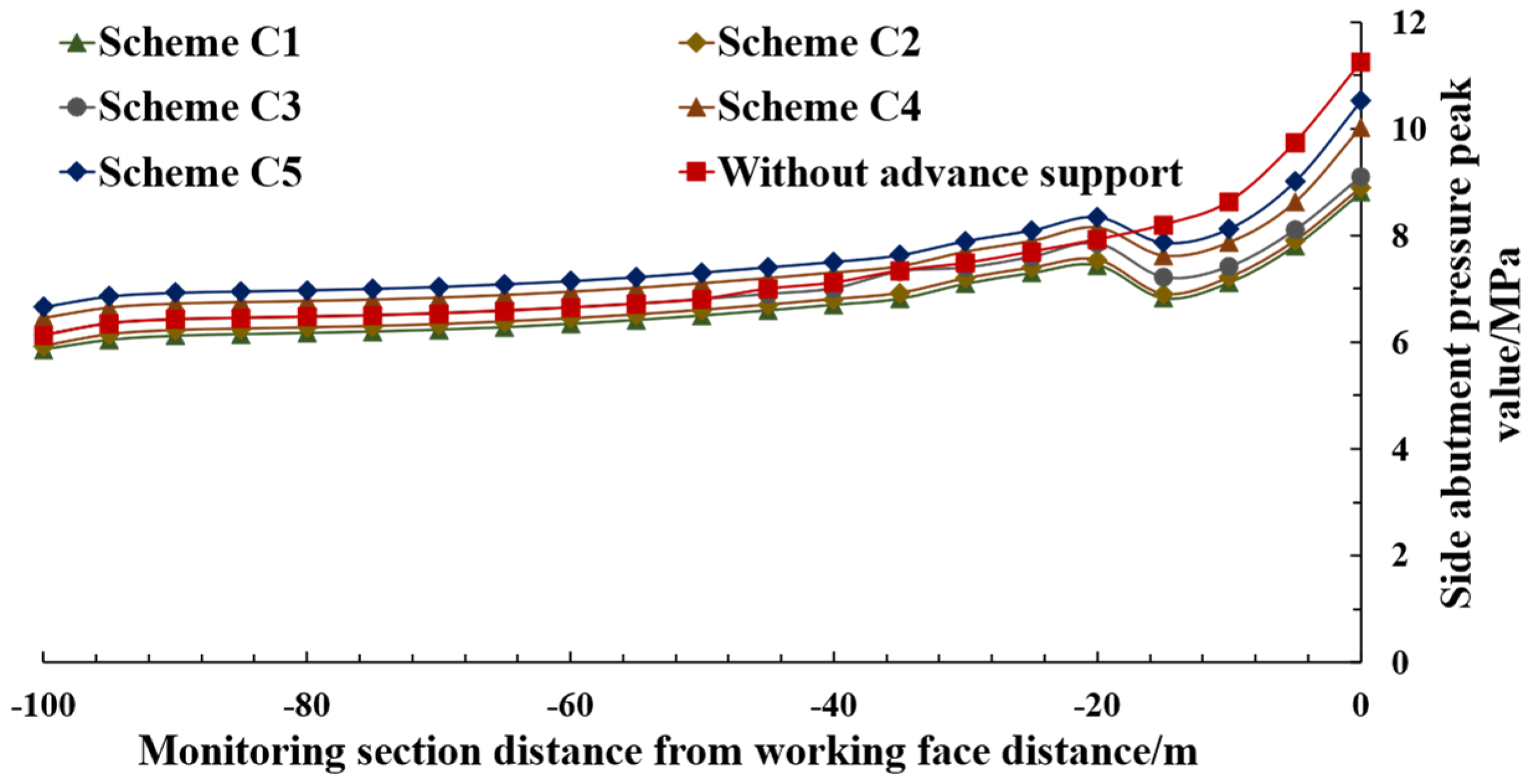

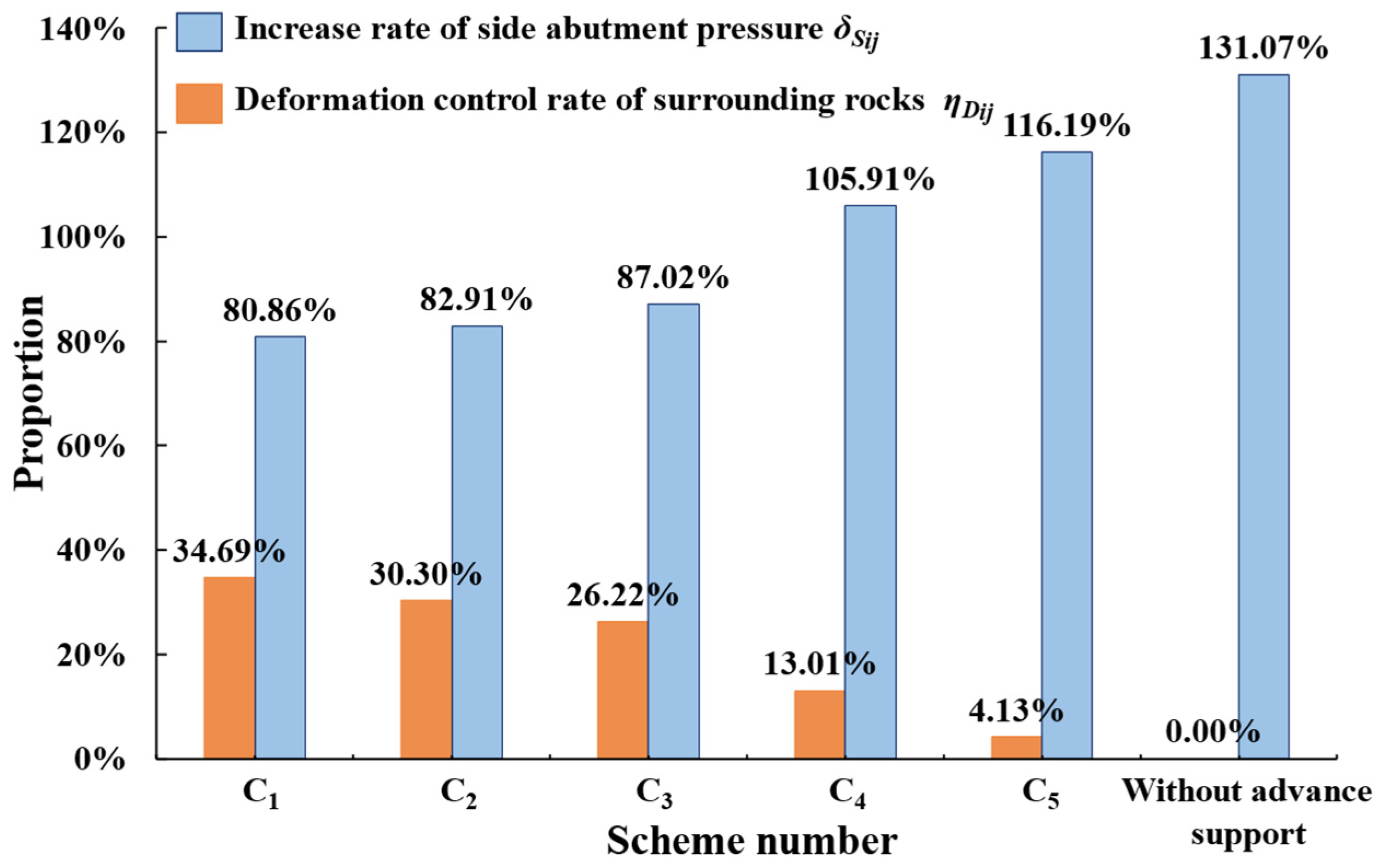

4.3.3. Result Analysis of Scheme C

This type of scheme (C

1~C

5) is compared and analyzed with the anchor cable spacing as a variable. The change curve of roof–floor convergence is plotted in

Figure 13. The evolution of the peak side abutment pressure is plotted in

Figure 14. The quantitative evaluation indexes of different anchor cable spacing are shown in

Figure 15.

(1) Deformation Control Efficiency: Anchor cables play a dominant role in controlling the deep displacement of the roof. As shown in

Figure 13, increasing the cable spacing weakens the suspension effect, causing the peak roof–floor convergence to rise from 12.50 mm to 17.85 mm. The quantitative efficiency is presented in

Figure 15, where the deformation control rates for schemes C

1~C

5 are calculated as 34.69%, 30.30%, 26.22%, 13.01%, and 4.13%, respectively. By analyzing the marginal gains, a distinct efficiency threshold is identified at 1.5 m. Specifically, reducing the spacing from 2.0 m to 1.5 m yields a substantial surge in control efficiency by 13.24%. However, further densification from 1.5 m to 1.2 m results in a minor improvement of only 4.08%. This sharp decline in marginal benefit indicates that reducing the spacing below 1.5 m provides limited additional stability relative to the increased material cost.

(2) Stress Concentration Mitigation: The evolution of side abutment pressure corroborates this finding. As the anchor cable spacing decreases, the peak side abutment pressure drops from 10.42 MPa to 8.82 MPa, indicating effective stress transfer. The increase rate of side abutment pressure decreases from the baseline of 131.07% (without advance support) to 116.19%, 105.91%, 87.02%, 82.91%, and 80.86% for schemes C

1–C

5, respectively (as shown in

Figure 15). Consistent with the deformation analysis, the capacity to mitigate stress concentration diminishes when the cable spacing is less than 1.5 m. Consequently, based on the dual criteria of maximizing control efficiency and minimizing cost, 1.5 m is determined as the optimal anchor cable spacing.

4.4. Discussion

The numerical simulation approach employed in this study, based on the finite difference method, is a standard and widely accepted tool in mining engineering for analyzing stress evolution. However, unlike previous studies that often simplified the roadside support as a boundary with constant stiffness, this research specifically incorporated the structural asymmetry induced by the flexible-formwork concrete (FFC) wall. The established model and the proposed quantitative evaluation indices have strong applicability to other medium-thickness coal seams with similar geological conditions, providing a reproducible reference for optimizing support parameters in asymmetric mining layouts:

(1) When the advance support range is less than 20 m, increasing the support range can significantly improve roadway control effect. But the influence on the roadway control effect is gradually reduced when the support range is greater than 20 m.

(2) When the hydraulic prop spacing is greater than 1.5 m, reducing the hydraulic prop spacing can significantly improve control effect. But reducing the hydraulic prop has no obvious influence on improving the control effect when the hydraulic prop spacing falls below 1.5 m.

(3) Reducing the anchor cable spacing can effectively improve the control effect. But when the anchor cable spacing falls below 1.5 m, it no longer significantly improves the control effect.

In conclusion, combined with the analysis of the actual engineering situation on the field, the optimal advance support scheme can be determined: the advance support range is 20 m, the advance hydraulic prop spacing is 1.5 m, and the anchor cable spacing is 1.5 m.

4.5. Economic and Environmental Assessment

The assessments are as follows:

(1) Economic Benefits: The primary economic contribution of the FFC-based GER technology is the recovery of non-renewable coal resources. In the conventional N1215 panel layout, a section coal pillar of 20 m width would be abandoned to isolate the goaf. By constructing the FFC roadside wall, this pillar is fully recovered during the mining of the adjacent panel. Although the initial construction cost of the FFC wall is higher than that of simple timber supports, the substantial economic value generated by the recovered coal resources significantly outweighs the material and labor costs of the wall, resulting in a higher profit margin per panel.

(2) Environmental Impacts: From an environmental perspective, this technology aligns with the principles of sustainable “Green Mining.” Firstly, retaining the entry eliminates the need to excavate a new roadway for the subsequent panel, thereby significantly reducing the discharge of gangue (waste rock) and minimizing land occupation on the surface. Secondly, the dense and continuous structure of the FFC wall provides superior airtightness compared to traditional loose-rock packing. This effectively isolates the goaf, preventing harmful gas leakage and reducing the risk of spontaneous combustion of residual coal in the goaf.

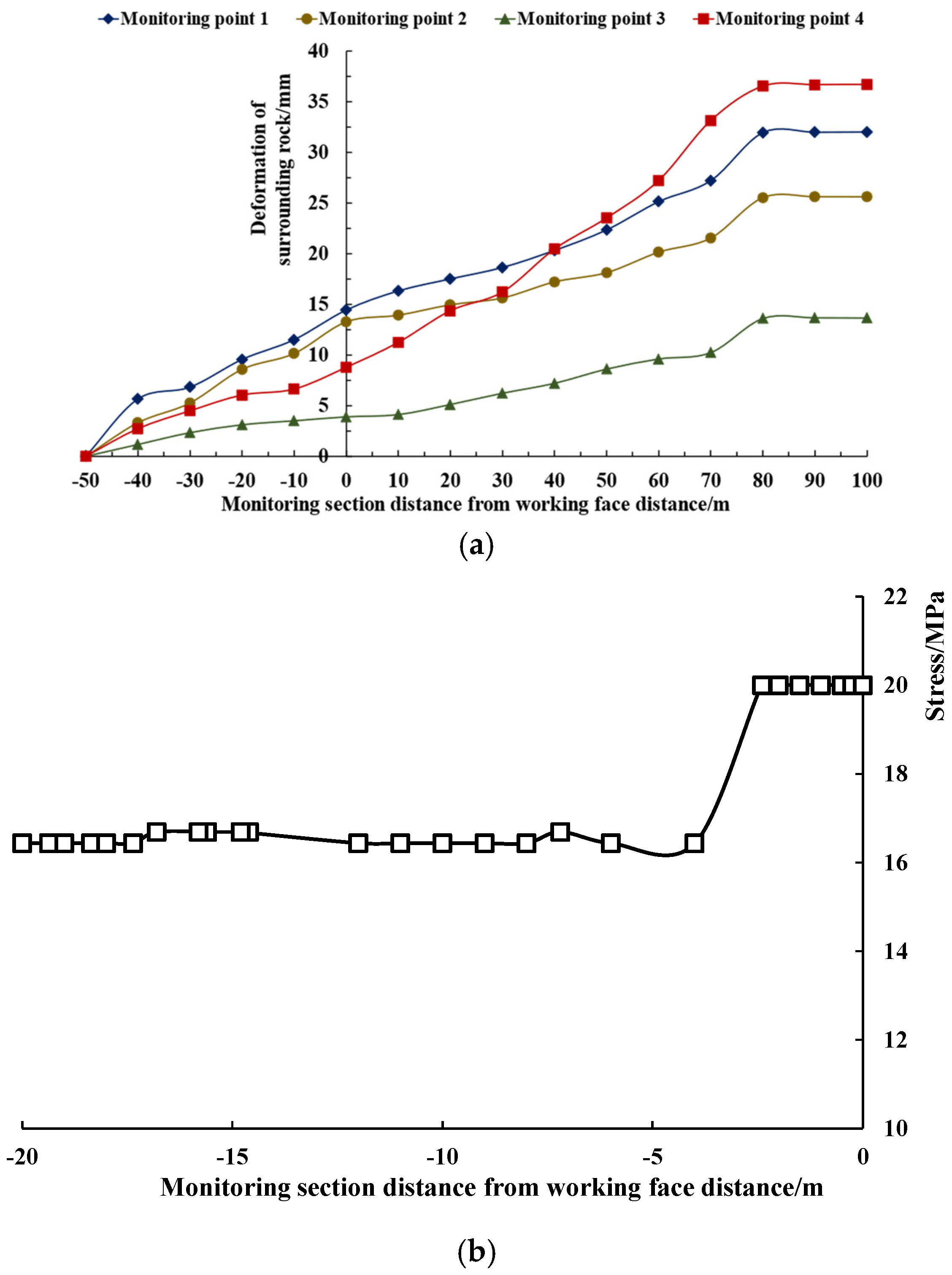

5. Field Application

Based on the above research, the N1215 fully mechanized mining working face of the Ningtiaota Coal Mine was selected for the field application of hydraulic-prop–anchor-coupling technology. The geological conditions were consistent with the previous paper. The passive support is supported by hydraulic prop, the spacing is 1.5 m, and the advance support range is 20 m. The roof adopts a Φ21.8 × 7000 mm anchor cable, and the row spacing is 2400 × 1500 mm. Field construction and application effects are shown in

Figure 16.

In order to verify the effect of field application, a monitoring section was set up at the typical position to monitor roadway displacement and force of hydraulic prop. The layout of which is as follows: Monitoring point 1 has a roof–floor convergence on the gob-side, monitoring point 2 has a roof–floor convergence in middle of roadway, monitoring 3 has a roof–floor convergence on the solid coal side, monitoring 4 has a rib convergence deformations. The monitoring results are presented in

Figure 17.

(1) With the mining of the working face, a gradual growth in roof–floor convergence and side convergence is observed in the advance segment. The maxima are 13.27 mm for roof–floor convergence and 8.78 mm for side convergence. In the entry-retaining segment, the convergence of surrounding rock shows a gradually increasing trend. The deformation reaches the peak at 80 m of lag face, and peak roof–floor convergence is 25.53 mm. The maximum rib convergence deformation is 36.51 mm. The roadway control effect meets the field safety requirements.

(2) As the working face advances, the working resistance of the hydraulic props exhibits distinct zonal characteristics. In the range of −20 m to −5 m from the working face, the resistance remains relatively stable at approximately 16.6 MPa, indicating a steady load-bearing state beyond the severe influence zone. Crucially, within the 0–5 m range, the resistance shows a rapid increasing trend due to the intensified advance abutment pressure. The resistance eventually peaks and stabilizes at 20.0 MPa. Despite this increase, the maximum working resistance remains well below the rated capacity of 32.0 MPa. This demonstrates that the support system not only meets the field control requirements but also maintains a sufficient safety margin to accommodate the dynamic pressure in the 0–5 m zone.

6. Conclusions

The conclusions are as follows:

(1) Mechanism of Asymmetric Damage: The time-dependent strength gain of FFC creates a distinct “weak window” in the early stage of entry retaining. This results in a structural and mechanical asymmetry—rigid solid coal versus the semi-cured FFC wall—which significantly aggravates roof fracturing in the advance pressure zone.

(2) Quantitative Evaluation of Support Efficiency: A quantitative evaluation system, comprising roof stress increase rate, side abutment pressure increase rate, and deformation control rate, was established. Numerical parametric analysis revealed that the marginal benefit of intensifying support parameters diminishes significantly beyond specific thresholds.

(3) Optimization Strategy: To compensate for the inherent boundary asymmetry, a “hydraulic prop-anchor cable coupled” advance support strategy was proposed. The optimal support parameters were determined as an advance support length of 20 m, a single hydraulic prop spacing of 1.0 m, and a roof anchor cable spacing of 1.5 m.

(4) Field Validation: The proposed strategy successfully effectively restrained the surrounding rock deformation in the N1215 panel of the Ningtiaota Coal Mine. Field monitoring confirmed that the maximum roof-to-floor convergence was controlled to 13.27 mm, ensuring the safety and stability of the retained entry during the mining process.

Author Contributions

Q.Q.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Investigation, Writing—original draft. W.G.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Funding acquisition. H.W.: Methodology, Resources, Funding acquisition, Data curation. M.H.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Funding acquisition, Data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps Key Areas Science and Technology Research Program, grant number 2025AB026; Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, grant number 2025D01C259; Science and Technology Plan Project of Kekedala City, the Fourth Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, grant number 2025ZR005; Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region “Tianshan Talents” Scientific Research Project-Young Top Talents, grant number 2023TSYCCX0081; Xin-jiang Uygur Autonomous Region Science and Technology Plan Project-Major Science and Technology Special Project, grant number 2024A03001-2; Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Science and Technology Plan Project-Major Science and Technology Special Project, grant number 2024A01002-1; Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Hami City Scientific Research and Technology Development Project, grant number hmkj2025004; and Xinjiang University Outstanding Postgraduate Innovation Project, grant number XJDX2025YJS109.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor for providing helpful suggestions for improving the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Chen, W.S.; Chen, F.; Ma, F.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Gao, H. A simulation experimental study on the advance support mechanism of a roadway used with the longwall coal mining method. Energies 2022, 15, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.S.; Zhu, W.C.; Niu, L.L. Experimental and numerical evaluation on debonding of fully grouted rockbolt under pull-out loading. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, Z.H.; He, M.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, B. Automatic roadway formation method by roof cutting with high strength bolt-grouting in deep coal mine and its validation. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 382–397. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.C.; Gao, Y.B.; Yang, J.; Guo, Z.B.; Wang, E.Y.; Wang, Y.J. An energy-gathered roof cutting technique in no-pillar mining and its impact on stress variation in surrounding rocks. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2017, 36, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.R.; Wu, Y.Y.; Chen, D.D.; Liu, R.; Han, X.; Ye, Q. Failure analysis and control technology of intersections of large-scale variable cross-section roadways in deep soft rock. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.B.; Gai, Q.K.; Zhang, X.X.; Xi, X.; He, M.C. Evaluation of roof cutting by directionally single cracking technique in automatic roadway formation for thick coal seam mining. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.L.; Tao, Z.G.; He, M.C.; Li, M.N.; Sui, Q.R. Numerical simulation study on shear resistance of anchorage joints considering tensile–shear fracture criterion of 2G-NPR bolt. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Yang, R.S.; Fang, S.Z.; Lin, H.; Lu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M. Failure analysis and control measures of deep roadway with composite roof: A case study. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Pan, R.; Li, S.-C.; He, M.-C.; Sun, H.-B.; Qin, Q.; Yu, H.-C.; Luan, Y.-C. Failure mechanism of surrounding rock with high stress and confined concrete support system. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 102, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Saini, M.S.; Singh, T.N.; Dutt, A.; Bajpai, R.K. Effect of excavation stages on stress and pore pressure changes for an underground nuclear repository. Arab. J. Geosci. 2011, 6, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Singh, T.N. Assessment of tunnel instability—A numerical approach. Arab. J. Geosci. 2009, 3, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.R.; Ma, Z.G.; Yang, D.W.; Qi, F.Z.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.H. Study on key parameters of filling gob-side roadway in the thick layer soft rock fault top. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2019, 36, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, C.; Gao, Y.; Hu, D.; Li, Z. Analysis of supporting resistance of reserved pier column for gob-side entry retaining in wide roadway. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 4218–4225. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.R.; Ren, Y.Q.; Wang, P.F.; Guo, J.; Qian, R.P.; Li, S.Y.; Hao, C.L. Stress distribution and deformation characteristics of roadside backfill body for gob-side entry of fully-mechanized caving in thick coal seam. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2019, 36, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.; Ma, X.G.; Pan, Z.F. Mechanism and comprehensive control techniques for large deformation of floor heave in block filling gob-side entry retaining. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2022, 39, 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Shan, R.L.; Huang, B.; Feng, J.; Peng, R. Similar model tests on strong sidewall and corner support of gob side entry retaining. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2021, 38, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.J.; Dong, C.W.; Yuan, Z.X.; Zhou, N.; Yin, W. Deformation behavior of gob-side filling body of gob-side retaining entry in the deep backfilling workface. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2020, 37, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zou, Y.; Gui, T.; Chen, F. Research on gob-side entry retaining technology inclined fully mechanized mining face with large mining height. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hou, S.; Shi, Z.; Yang, F.; Liu, X.; Du, F. Study on failure mechanisms of surrounding rock in large-mining-height soft-roof working face and technology of roof-cutting automatic roadway formation: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 162, 108421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, G.; Niu, Z.; Lu, H. Study on the Stability and Control of Gob-Side Entry Retaining in Paste Backfill Working Face. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Li, G.F. Bolt support technology for gob-side entry retaining. Ground Press. Strat. Control 2002, 19, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.Y. Technology of roadway retained for next sublevel in Kaolinite of coal series strata. Coal Sci. Technol. 2003, 31, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.G.; Bai, J.B.; Hou, C.J. Study on the main parameters of gateside packs in gateways maintained along gob-edges. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 1992, 21, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.J.; Xu, J.H.; Ni, H.M. The small aspect ratio backfill gob-side entry retaining stability. J. China Coal Soc. 2010, 35, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.J.; Xu, J.H.; Liang, G.D.; Hu, Z.G.; Zhang, J.Y. Technology of goaf side gateway retained with roof falling rock natural backfilling in inclined seam. Coal Sci. Technol. 2010, 38, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.H.; Tang, J.X.; Zhu, X.K.; Fu, Y.; Hu, H. Industrial test of concrete packing for gob-side entry retained in gently-inclined medium-thickness coal seam. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2011, 46, 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.X.; Hu, H.; Tu, X.D.; Deng, Y.H. Experimental on roadside packing gob-side entry retaining for ordinary concrete. J. China Coal Soc. 2010, 35, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.F.; Hua, X.Z.; Cai, R.C. Mechanics Analysis on the Stability of key block in the gob-side entry retaining and engineering application. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2012, 29, 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.B.; Zhou, H.Q.; Hou, C.J. Development of support technology beside roadway in goaf-side entry retaining for next sublevel. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2004, 33, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.; Chen, D.D.; Xie, S.R.; Guo, F.F.; Wu, Y.Y.; Yang, H.Z. Study on deviatoric stress distribution and control technology of surrounding rock at gob-side entry retaining with dual-roadways. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2022, 39, 557–566. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.F.; Wang, E.; Chen, D.D.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, P.; Dong, Z.; Yan, Z.; Xiao, H. Evolution of deviatoric stress and control of surrounding rock at gob-side entry retaining with narrow flexible-formwork wall. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Fu, Q.; Zhou, K.F.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, B.H. Technology of flexible formwork concrete in gob-side entry retaining automatically with no-pillar in thick coal seams. Coal Eng. 2019, 51, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Zhao, H.L.; Cao, X.Y. Design of small coal pillar reinforcement and double flexible-formwork wall support for retained entry in extra thick coal seam. Coal Eng. 2022, 54, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.F.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.L.; Yang, Z.; Li, A. Research analytics on the applications of flexible formwork gob-side entry retention technology in medium-thickness coal seams with large inclination angles. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, J.Q. Research on the Deformation and Failure Mechanism of Flexible Formwork Walls in Gob-Side-Entry Retaining of Ultra-Long Isolated Mining Faces. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

N1215 working face overview.

Figure 1.

N1215 working face overview.

Figure 2.

Roadside support section diagram of N1215 belt transport roadway.

Figure 2.

Roadside support section diagram of N1215 belt transport roadway.

Figure 3.

Field damage observation.

Figure 3.

Field damage observation.

Figure 4.

Fracture of roadway roof.

Figure 4.

Fracture of roadway roof.

Figure 5.

Numerical calculation mode.

Figure 5.

Numerical calculation mode.

Figure 6.

The variation of roadway roof stress in the advance segment without advance support.

Figure 6.

The variation of roadway roof stress in the advance segment without advance support.

Figure 7.

Variation curve of roof–floor convergence.

Figure 7.

Variation curve of roof–floor convergence.

Figure 8.

Evolution of the peak side abutment pressure.

Figure 8.

Evolution of the peak side abutment pressure.

Figure 9.

Quantitative evaluation index.

Figure 9.

Quantitative evaluation index.

Figure 10.

Variation curve of roof–floor convergence.

Figure 10.

Variation curve of roof–floor convergence.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the peak side abutment pressure.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the peak side abutment pressure.

Figure 12.

Quantitative evaluation index.

Figure 12.

Quantitative evaluation index.

Figure 13.

Variation curve of the roof–floor convergence.

Figure 13.

Variation curve of the roof–floor convergence.

Figure 14.

Evolution of the peak side abutment pressure.

Figure 14.

Evolution of the peak side abutment pressure.

Figure 15.

Quantitative evaluation index.

Figure 15.

Quantitative evaluation index.

Figure 16.

Field application effect of support scheme.

Figure 16.

Field application effect of support scheme.

Figure 17.

Roadway deformation and hydraulic prop stress. (a) Displacement of surrounding rock surface. (b) Hydraulic prop stress.

Figure 17.

Roadway deformation and hydraulic prop stress. (a) Displacement of surrounding rock surface. (b) Hydraulic prop stress.

Table 1.

Each stratum parameters.

Table 1.

Each stratum parameters.

| Stratum | Thickness

/m | Density

/(kg·m−3) | Cohesion

/MPa | Internal Friction Angle

/(°) | Tensile Strength

/MPa |

|---|

| Medium-grained sandstone | 92.6 | 2075 | 1.08 | 41.54 | 0.576 |

| Siltstone | 15.6 | 2034 | 1.51 | 39.15 | 0.864 |

| 2−2 Coal | 2.1 | 1070 | 0.94 | 28.88 | 0.36 |

| Siltstone | 2.6 | 1993 | 1.29 | 40.98 | 0.792 |

| 2−2 below Coal | 1.5 | 1070 | 0.94 | 38.58 | 0.288 |

| Siltstone | 17.8 | 2025 | 1.37 | 40.08 | 0.936 |

Table 2.

Comparative analysis scheme of advance support ranges.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis scheme of advance support ranges.

| Scheme Number | Advance Support Range | Invariants |

|---|

| A1 | 10 m | Hydraulic prop spacing 1.5 m

Anchor cable spacing 1.5 m |

| A2 | 20 m |

| A3 | 30 m |

| A4 | 40 m |

| A5 | 50 m |

Table 3.

Comparative analysis scheme of advance hydraulic prop spacing.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis scheme of advance hydraulic prop spacing.

| Scheme Number | Advance Hydraulic Prop Spacing | Invariants |

|---|

| B1 | 1.0 m | Advance support range 20 m

Anchor cable spacing 1.5 m |

| B2 | 1.5 m |

| B3 | 2.0 m |

| B4 | 2.5 m |

Table 4.

Comparative analysis scheme of anchor cable spacing.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis scheme of anchor cable spacing.

| Scheme Number | Anchor Cable Spacing | Invariants |

|---|

| C1 | 1.0 m | Advance support range 20 m

Hydraulic prop spacing 1.5 m |

| C2 | 1.2 m |

| C3 | 1.5 m |

| C4 | 2.0 m |

| C5 | 2.5 m |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |