1. Introduction

Statistical modelling is a tool employed across several scientific and engineering disciplines to elucidate mathematical relationships in real-world data. The development of new statistical distributions plays a central role in enhancing this process, particularly in cases where existing models do not have an efficient capability to meet this goal. In order to construct an efficient distribution that is flexible and has high capability to deal with real-world data, the T-X family framework is employed. The T-X framework, presented by [

1], provides a general method for generating new probability distributions by applying a transformation function (T) to a baseline distribution, together with an auxiliary random variable (X). The addition of extra shape parameters enhances the model’s capability, adaptability, and flexibility in capturing real-world phenomena. These extra features strengthen modelling in reliability analysis, survival analysis studies, and lifetime data analysis, where data exhibit skewness, heavy tails, or multimodal behaviours; the conditions under which standard normal models show inadequacy.

One of the commonly studied distributions is the Weibull distribution. It is a widely used model in lifetime data analysis that has undergone various modifications to improve its flexibility. Notably, extensions such as the flexible Weibull [

2] and exponentiated Weibull [

3], have been proposed to accommodate non-monotonic hazard functions. Other modifications proposed include the Alpha logarithmic transform Weibull (ALTW) distribution [

4], the beta-Weibull distribution by [

5], the Kumaraswamy Weibull Distribution [

6], and the beta modified Weibull distribution by [

7]. Furthermore, the additive modified Weibull distribution proposed by [

8], ref. [

9] presented a five-parameter distribution from the family of Marshall Olkin distributions called Marshall Olkin Weibull-Burr XII and the Topp-Leone modified Weibull Model introduced by [

10], and application of the Weibull Half-Laplace [

11].

Similarly, modifications to the Rayleigh distribution, such as the exponentiated Weibull Rayleigh distribution due to [

12], parameter estimation of Weibull Rayleigh [

13], Weibull inverse Rayleigh [

14], beta generalized Inverse Rayleigh distribution presented by [

15], the exponentiated Rayleigh [

16], have aimed at enhancing its ability to model skewed and heavy-tailed data. The extensive modifications of the Weibull and Rayleigh distributions have demonstrated the need for more flexible statistical models capable of capturing diverse hazard-rate behaviours and accommodating heavy-tailed data. Previous studies have introduced many extensions of classical distributions, such as exponentiated forms and inverse-type modifications, primarily to improve model fit to real data. Even with these developments, many lifetime distributions still struggle when the data show non-monotonic hazard rates, a pattern that often appears but is not easy to capture. This limitation suggests the need for models that are more flexible and can borrow strengths across different families without inheriting their weaknesses.

In this work, we propose the Hybrid Weibull–Exponentiated Rayleigh Distribution (HWERD) as an attempt to bridge that gap. In developing the HWERD, we used the T-X framework, taking the exponentiated Rayleigh distribution as the starting point and then applying a Weibull-type transformation. This combination combines properties of both distributions, providing the new model with additional flexibility when analyzing lifetime or reliability data. We note that the original formulation with four parameters () is non-identifiable because the parameters and appear only through their product . Therefore, we present a three-parameter model () that is identifiable and retains the flexibility of the original formulation. As the results show, it can offer improved parameter estimation and a better overall fit compared to several existing alternatives.

Another area to explore is how the model behaves symmetrically. In reliability and survival analysis, the data is rarely perfectly symmetric. Often, failure times are skewed. There may be failures or a long tail of late failures. The shape parameters of the HWERD give an idea of skewness. When we examine how the shape parameters control the asymmetry, we can see the symmetry of the process that generates the data. This line of inquiry fits well within the broader scope of studying symmetry in mathematical models.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The methodology framework is presented in

Section 2,

Section 3 includes the simulation studies, real dataset application, results, and discussion,

Section 4 presents the conclusions and future work direction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Formulation of HWERD

The T-X framework provides a general method for creating new distribution families by applying a transformation to a baseline cumulative distribution function (CDF). For the HWERD, we start with the CDF of the exponentiated Rayleigh distribution and apply the Weibull transformation.

Let the CDF of the exponentiated Rayleigh distribution be

where

and

are shape parameters.

The CDF of the Weibull distribution is as follows:

where

and

are shape parameters.

The T-X framework with Weibull transformer applied to

yields the following:

However, this construction leads to a defective distribution because

. To obtain a proper distribution, we need to apply the Weibull transformation to the survival function of the exponentiated Rayleigh distribution, yielding the Weibull-G family:

Substituting

from Equation (

1) yields the following:

We observe that the parameters and appear only through their positions in the nested structure. To ensure identifiability and reduce the number of parameters while maintaining flexibility, we propose the following reparameterization.

Proposed 3-Parameter Model: Let

and reparameterize to obtain the following:

where

,

, and

.

This corrected formulation ensures that , making it a proper probability distribution.

To obtain the probability density function (PDF), we differentiate

with respect to

x:

Thus, the PDF of the three-parameter HWERD is as follows:

The support of the distribution is

, and it can be verified that

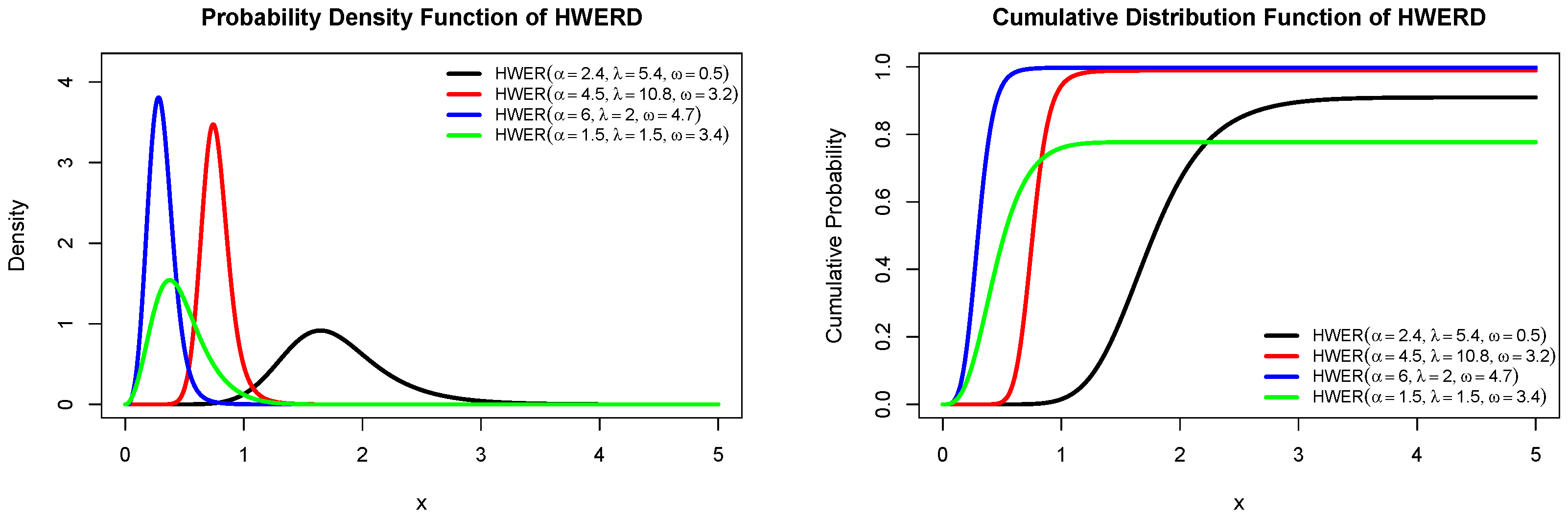

The HWERD PDF plot in

Figure 1 shows how variations in the combination of parameters affected the shape and the spread of the density function. The PDF curves are predominantly unimodal and right-skewed, which shows that higher values of

and

move the HWERD peak near smaller

X values, indicating short lifetimes or a higher rate of event occurrence. However, there are more dispersed event times at small values of

that yield flatter, broader curves, suggesting longer-tailed distributions.

The CDF plot shows the corresponding cumulative probabilities for the parameter sets. As expected from a valid cumulative distribution, the curves increase monotonically from 0 to 1. Curves associated with larger values of and rise more sharply, signifying a higher likelihood of events occurring early and a faster accumulation of probability.

Furthermore, by setting parameters to different values,

Figure 1 displays the capability of the HWERD to capture a range of lifetime behaviours. The ability of HWERD to model data with different survival or failure features is illustrated by its ability to yield strongly spiked and more spread-out shapes. For example, quick failures resonate with higher values of

and

, while prolonged survival times are associated with smaller parameter values. Due to this versatility, the HWERD is a strong choice for applications related to lifetime, including survival modelling and reliability studies, where hazard trends can vary substantially across datasets.

2.2. Statistical Properties of HWERD

It is very important to examine the distributional properties of the proposed model to understand its behaviour and uniqueness. The properties include the moments, order statistics, entropy, and reliability functions. This examination gives clear insight to the flexibility of the model.

2.2.1. Survival and Hazard Functions

Reliability analysis helps determine whether a system or component performs well over time without failure. Interpreting the usefulness of the proposed distribution in lifetime or survival studies will be easier by understanding its reliability behaviour. The survival and hazard rate functions of model HWERD are presented in this section.

The survival function is given by the following:

The derivation of the HWERD hazard function is as follows:

Taking out the like terms, the hazard function simplifies to the following:

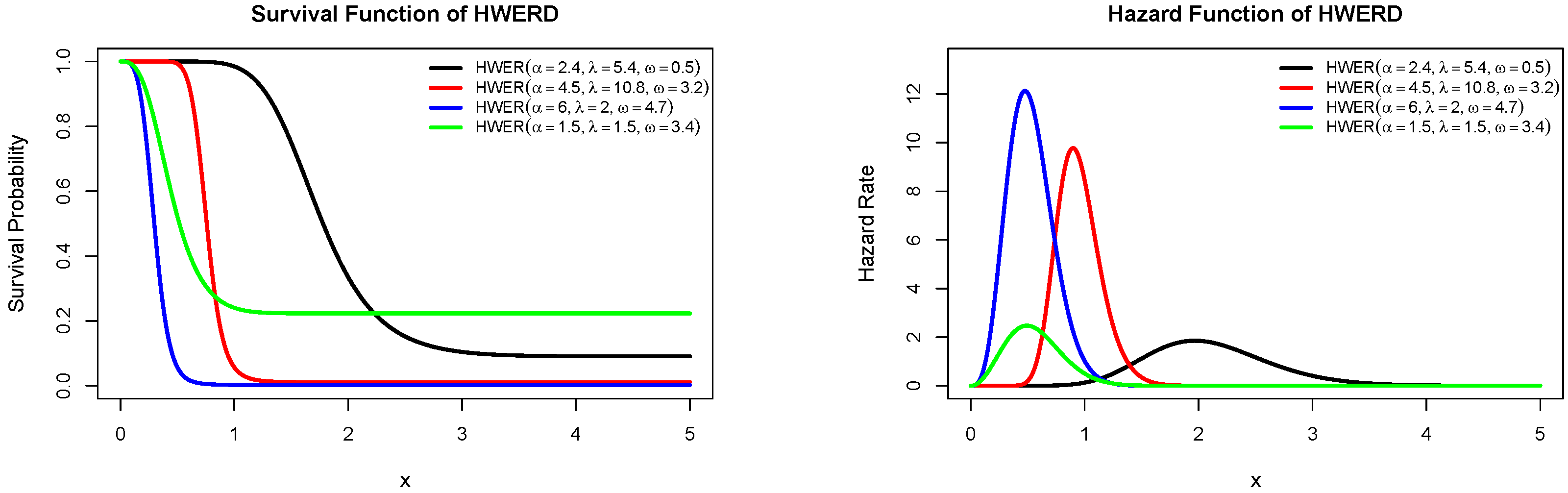

Figure 2’s HWERD survival and hazard plots provide important information about the reliability characteristics that are regulated by its parameter. The probability of survival decreased steadily, as evidenced by the decline in the survival curves. Higher parameter values accelerate this by showing faster rates of deterioration, whereas lower parameter values indicate longer survival. The hazard plot exhibits a unimodal failure rate with non-monotonic behavior, characterized by an initial increase followed by a decrease. It indicates that the HWERD captures early failures, the wear-out period, and a constant operational phase. From these plots, HWERD exhibits the flexibility and sustainability of modelling different lifetime behaviors in reliability and survival studies.

2.2.2. Linear Representation

For a clearer mathematical structure, it is helpful to express the distribution in a linear form. The linear representation of the model is presented in this section.

Proposition 1. If a random variable X follows an HWER distribution, then its PDF can be expressed as a linear combination of modified Inverse Rayleigh (or Exponentiated Rayleigh) densities.

Proof. Given the PDF of HWERD from Equation (

9):

Expanding the exponential term using the Taylor series:

Substituting Equation (

9) into Equation (

13):

We can rearrange the terms:

Now, expand

using the binomial theorem:

Substituting Equation (

17) into Equation (

18):

Combine the exponential terms:

Therefore, the final linear representation of HWERD is as follows:

□

2.2.3. Quantile Function of HWERD

In this section, the quantile function of the proposed HWERD is presented. It is majorly useful in describing percentiles and generating random samples from the distribution.

Proposition 2. If X is a random variable that follows the HWER distribution, then the quantile function for is given by the following:

Proof. From Equation (

4), we have the following:

Setting

, we get the following:

Taking the natural logarithm on both sides:

Thus, the quantile function is as follows:

□

2.2.4. Moments, Skewness, and Kurtosis

Moments are essential for describing the shape, center, and spread of a probability distribution. The

raw moment is defined as follows:

Proposition 3. Given a random variable X that follows a HWER distribution with parameters α, λ, and ω, the moment of the HWERD is given by the following:

Proof. Using the linear representation of HWERD from Equation (

21):

Substituting into the moment definition:

Now, evaluate the integral using the Gamma function. Let

, then

and

. Thus:

Substituting back gives the following:

This can be written more compactly as follows:

where

□

First and Second Moments: From the general formula, we obtain specific moments:

First Moment (Mean): Setting

:

since

.

Second Moment: Setting

:

since

.

Variance: The variance is obtained from .

Skewness and Kurtosis: To assess whether the data are symmetric, the skewness measure is used. A value near zero points to a roughly symmetric bell shape. The further it gets from zero, the more asymmetric or skewed the distribution becomes. Since our model allows this value to vary, it enables us to directly test and model the level of symmetry in a dataset. Because the distribution does not have simple closed-form expressions for skewness and kurtosis via moments, we use quantile-based measures [

17,

18] skewness and kurtosis as stated below. Alternatively, moment-based measures can be computed numerically using the moment formulas above.

Quantile function of HWERD:

2.2.5. Order Statistics of HWERD

To study the behaviour of the smallest and largest observations in a sample, order statistics are essential. The order statistics for the proposed model, HWERD, are presented in this part.

Proposition 4. Let be a random sample from the HWERD. Let be the corresponding order statistics. Then the PDF of the s-th order statistic for the HWERD is given by the following: Proof. The PDF of the

s-th order statistic is given by the following:

where

and

are the PDF and CDF of HWERD, respectively.

Using the binomial series expansion of

, we obtain the following:

Substituting Equation (

41) into Equation (

40):

Now, expand

using the binomial theorem:

From the HWERD PDF in Equation (

9):

Substituting Eqsuations (41) and (42) into Equation (

40):

Now, expand the exponential term using the Taylor series:

Substituting Equation (

44) into Equation (

43):

Now, expand

using the binomial theorem:

Substituting Equation (

46) into Equation (

45):

Combine the exponential terms:

Therefore, the PDF of the

s-th order statistic is as follows:

For simplicity and to match the infinite series representation from Proposition 1, we can extend the upper limits to infinity, which gives the final form:

□

2.2.6. Shannon Entropy

The Shannon entropy quantifies the degree of uncertainty or randomness in a probability distribution. For a continuous random variable

X with PDF

, the Shannon entropy is defined as follows:

For the HWERD, substituting the PDF from Equation (

7) gives the following:

This expression does not simplify to a closed form in terms of elementary functions. However, it can be expressed in series form using the linear representation. For practical applications, we recommend computing the Shannon entropy numerically.

2.3. Model Identifiability and Reparameterization

A statistical model is said to be identifiable if distinct parameter values produce distinct probability distributions. Identifiability is a fundamental requirement for meaningful statistical inference, as it ensures that model parameters can be uniquely recovered from the observed data.

Let

denote the parameter vector of the Hybrid Weibull–Exponentiated Rayleigh Distribution (HWERD). The model is identifiable if

Consider two parameter vectors

and

. From the probability density function of the HWERD,

equality of densities for all

implies equality of their logarithms. By examining the limiting behavior of the density as

and

, the exponential decay term

uniquely determines

, yielding

. Substituting this result back into the density and comparing the remaining terms implies

, and consequently

. Hence, the HWERD is identifiable.

An alternative argument follows from the quantile function of the HWERD. If two parameter vectors yield the same quantile function for all , then the corresponding distributions must coincide. Since the quantile function is injective in , this further establishes identifiability.

Practical estimation indicates a high reliance between the parameters

and

even though the HWERD is identifiable in its original form. To address this problem and enhance numerical stability, a reparameterization is proposed by defining

Under this transformation, the parameter vector becomes

, with

.

In addition to lowering parameter correlation and increasing the stability of maximum likelihood estimation, this reparameterization maintains identifiability. Therefore, the reparameterized form of the HWERD is used in all the following inference, simulation investigations, and applications in this study.

The identifiability of HWERD guarantees valid statistical inference based on these parameters and well-defined parameter estimation. The consistency of maximum likelihood estimators depends on this feature.

2.4. Parameter Estimation

The method used to estimate the HWERD parameters is maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). Let

be a random sample of size

n drawn from the HWERD distribution

. The probability density function is given by the following:

The likelihood function is as follows:

Taking the natural logarithm of the likelihood function, we get the log-likelihood:

To obtain the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameter vector

, we differentiate Equation (

60) with respect to each parameter and set it to zero. The numerical approach used to maximize the log-likelihood function is the Newton–Raphson method or another optimization algorithm.

The asymptotic distribution of the maximum likelihood estimator

is given by

where

is the inverse of the expected Fisher information matrix.

2.4.1. Initial Values and Optimization

To ensure reliable convergence of the maximum likelihood estimators, the following strategies were adopted:

Method-of-moments estimates were used to obtain suitable initial values.

Multiple starting points were employed to reduce the risk of convergence to local optima.

Log-transformations were applied to parameters to enforce positivity constraints.

Robust numerical optimization algorithms with parameter bounds were utilized.

2.4.2. Model Validation Checks

To confirm the proposed model’s numerical stability and mathematical validity, the following validation procedures were implemented:

Verification that the cumulative distribution function approaches unity as .

Numerical confirmation that the probability density function integrates to one.

Comparison of simulated sample moments with their theoretical counterparts.

Assessment of quantile–quantile plots to evaluate parameter recovery.

3. Results

The performance of the HWERD is studied for robustness and superiority through simulations and real-data applications. Using relevant tables and figures to provide a more thorough explanation, this section examines the conclusions drawn from statistical analysis, simulation results, and real-world dataset applications.

3.1. Simulation Study

The simulation was done using the quantile function of the HWER distribution. Parameter estimations were obtained using the maximum likelihood estimator. The procedures for the simulation study to estimate HWERD parameters are described below:

The sample sizes are fixed as and 1000.

Random variable X from the quantile function is used to generate the dataset.

Setting the parameter to different values.

The process is repeated 1000 times.

The above procedure is repeated using maximum likelihood estimators.

Bias: the estimated bias of the parameter estimator, computed as follows:

where

is the average of 1000 estimates, and

is the true parameter value.

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): the estimated root mean square error, measuring the accuracy of the parameter estimates:

Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of the estimated parameters are also obtained.

The parameter estimates and their standard errors for different sample sizes are shown in

Table 1. The results support the effectiveness and stability of the estimators, demonstrating improved accuracy, depicting the accuracy of the estimation as the sample size increases. Standard errors decrease as the sample size increases, indicating greater stability of the estimators for larger samples. The results suggest that the estimators behave well, with their accuracy and precision improving steadily as the sample size increases. Consequently, based on the findings of this simulation study, we affirm that the maximum likelihood estimation method is suitable for estimating the parameters of the HWERD model. The results show that MLE provides stable and consistent estimates across sample sizes.

Further insight into the HWERD’s shape characteristics comes from skewness and kurtosis measurements.

Table 2 reports the mean, median, skewness, kurtosis, and standard deviation for several parameter combinations and sample sizes. The results show that kurtosis varies with sample size: In some cases, it takes negative values, implying lighter tails compared with the normal distribution, while in others it becomes quite high, suggesting the presence of heavy tails. This pattern highlights the HWERD’s flexibility in modeling distributions with different tail behaviors.

At larger sample sizes, the standard deviation remains relatively stable, which reinforces the reliability of HWERD for estimating parameters with minimal fluctuation. The observed variations in skewness and kurtosis across parameter settings further illustrate the distribution’s adaptability to different data patterns, making it particularly useful for analyzing complex or heterogeneous datasets.

Table 3 presents the estimated bias and RMSE values for different sample sizes and true parameter values. As the sample size increases, both bias and RMSE consistently decline for parameter sets 1 to 3, once again confirming the robustness and accuracy of the proposed estimation method. This is consistent where estimators become more accurate and stable when sample sizes are higher. When the true value of

is 1.1 for parameter set 1, the RMSE decreases from 0.1095 at a sample size of 50 to 0.0.0552 at a sample size of 1000. This is also evident for other parameters. In general, from the results, there is an indication that the estimators performed well as the sample size increased, demonstrating the robustness of the estimation techniques.

3.2. Application of HWERD to Real Datasets

The HWER distribution is fitted to real datasets that include data on remission duration for bladder cancer patients and the breaking stress of carbon fibers. The results of HWERD’s performance in relation to existing distributions are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5. All models were estimated using the MLE method. The performance of the model was evaluated on the basis of the commonly used model selection criteria, that is, AIC, BIC, and HQIC. These evaluate how well the model fits its complexity, penalizing the number of parameters to avoid overfitting.

3.2.1. Dataset 1

HWERD was applied to the bladder cancer remission time data for 128 patients, initially reported in [

19]. The description of the data is monthly remission times until recurrence after treatment, and has been widely utilized in the lifetime distribution. The data is presented in

Table A1. Among the studies that have analyzed the dataset are [

20,

21,

22]. The HWERD model was compared with other well-known distributions, which include Weibull exponential, exponentiated Weibull exponential, exponentiated exponential, and exponentiated Weibull Rayleigh.

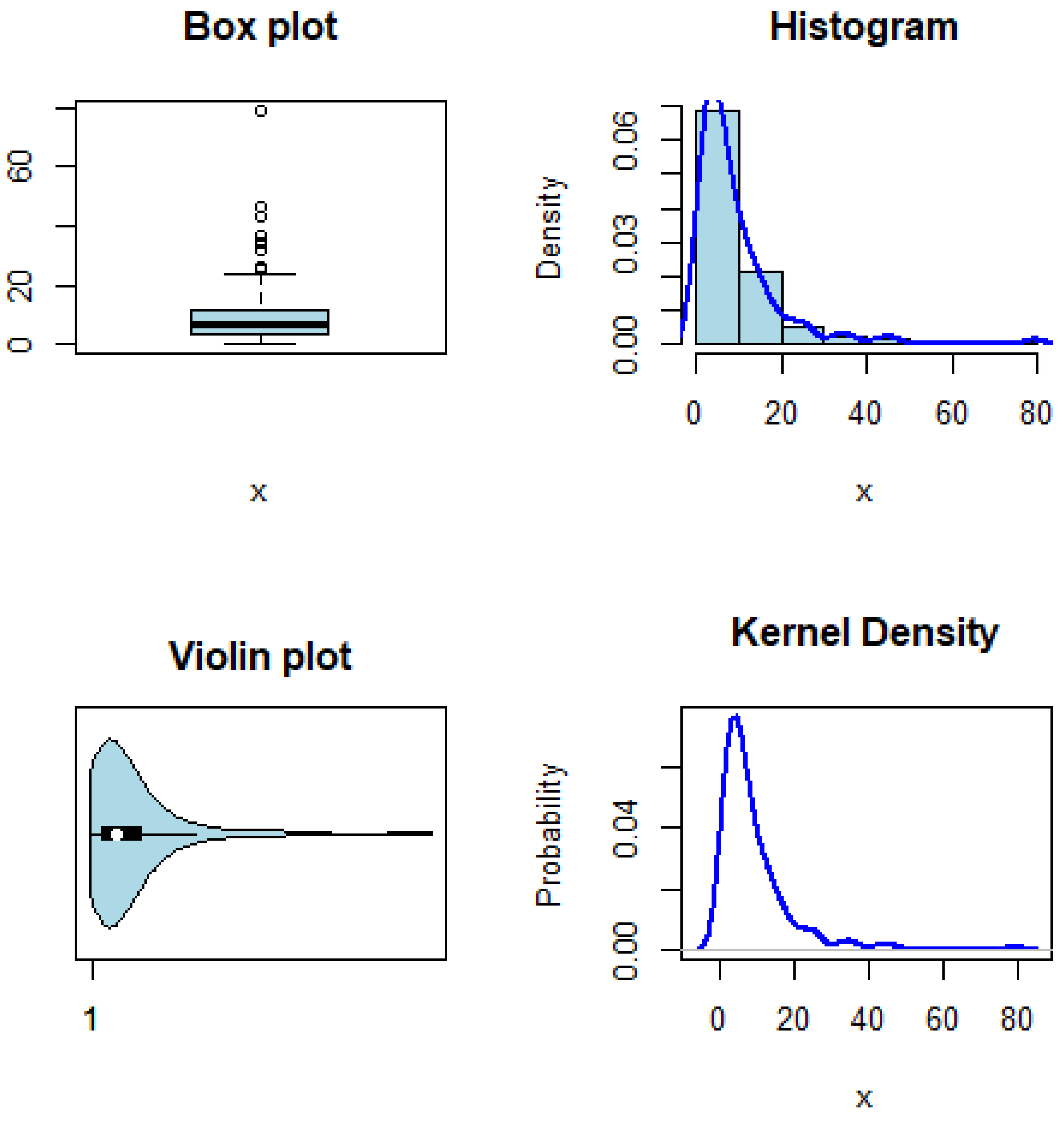

Figure 3 presents exploratory plots of the remission time data. The boxplot and violin plot reveal a right-skewed distribution with the majority of remission times clustered at shorter durations. These illustrations demonstrate how well HWERD models long-tailed distributions, making it a strong, viable choice for survival analysis in medical research.

Table 4 presents the results, which indicate that HWERD outperforms other considered distributions such as Exponentiated Weibull Exponential distribution (EWED), Exponentiated Weibull Rayleigh distribution (EWRD), Weibull Exponential distribution (WED), and Exponentiated Exponential distribution (EED). For bladder cancer remission data, the HWERD distribution has the lowest AIC value of 832.261 and the lowest BIC value of 840.821, thus providing a better fit than that provided by any other considered model for this medical survival data set.

The HWERD provides the best fit according to all information criteria. It is notable that the estimate for the shape parameter is very close to zero () with a relatively small standard error. This indicates the ability of the model to adjust towards simpler nested forms when appropriate, without compromising its overall flexibility when needed. Nevertheless, the full HWERD formulation achieved the optimal balance between fit and complexity for this data.

3.2.2. Dataset 2

The second dataset presented in

Table A2 consists of the breaking stress of carbon fibers, measured across 50 fiber lengths which was firstly reported by [

23]. The dataset has been analyzed in various studies such as reliability and lifetime [

24,

25,

26]. To use the dataset, an experiment with 1000 simulation runs was conducted, and the HWERD was assessed against other existing models, including Weibull exponential, exponentiated Weibull exponential, exponentiated exponential, and exponentiated Weibull Rayleigh distributions.

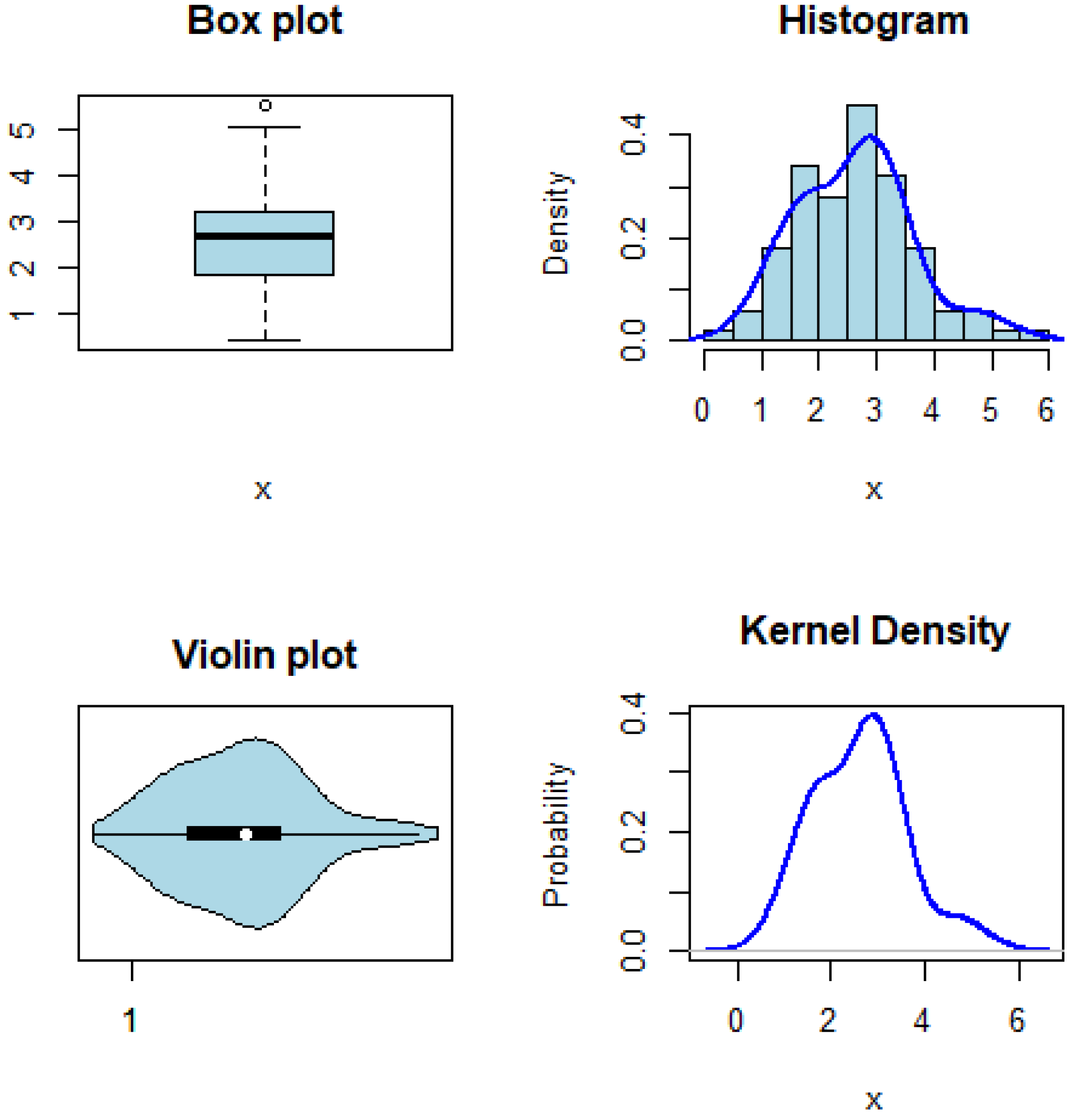

The distribution of the break-stress values is shown in

Figure 4, where HWERD effectively represents the variation in the failure rates of the material.

The results of the model comparison for the break Stress of Carbon fiber data are displayed in

Table 5. HWERD achieves the lowest values in all criteria, indicating that it offers the optimal balance between fit and model complexity. Among all fitted models, HWERD yielded the smallest AIC (288.57), indicating the best overall fit of the data, given model complexity and fit. The BIC and HQIC values of HWERD (296.40 and 291.74, respectively) were also the lowest among all models to further confirm its better performance.

4. Conclusions

This paper proposes a new lifetime distribution, the Hybrid Weibull–Exponentiated Rayleigh Distribution (HWERD). The model is obtained by combining the Weibull and Exponentiated Rayleigh distributions via the T-X framework, yielding a flexible form that can accommodate a range of failure-rate behaviours. It is particularly useful in cases where the hazard function is non-monotonic, a feature often encountered in data from engineering systems, medical survival studies, and environmental processes. To ensure identifiability, we presented a three-parameter reparameterization where captures the combined shape effect.

The HWERD successfully combines the strengths of the Weibull and Exponentiated Rayleigh distributions, enabling it to exhibit a wide range of hazard functions, including non-monotonic forms, and handle data with large tails. In this study, we examine several properties of the model, including its survival and hazard functions, moments (including skewness and kurtosis), and a linear representation. We also estimated the model parameters using maximum likelihood estimation. A comprehensive simulation study across diverse parameter values showed that the MLE estimators are consistent and stable, with accuracy and precision improving as sample size increases.

Finally, the HWERD was applied to two real-world datasets: bladder cancer remission times and the breaking stress of carbon fibers. In both applications, the HWERD provided a noticeably better fit than the existing models, as reflected by lower AIC, BIC, and other goodness-of-fit measures. The findings suggest that HWERD is well-suited to describe complex data patterns, particularly those exhibiting skewness, high kurtosis, or heavy tails. In general, the HWERD distribution is a strong and versatile model for lifetime and reliability data. Its mathematical tractability, strong estimation performance, and superior goodness-of-fit indicate potential future applications.

Overall, the HWERD provides a practical three-parameter model with a clear and interpretable structure for examining symmetry in data. Its parameters offer direct and intuitive control over the distributional shape, including skewness, making the model particularly useful in applications where understanding asymmetry in failure times or material strength is important.

Future research will investigate robust estimation techniques for HWERD parameters in order to compare with MLE and their applications in other domains. Further theoretical work will characterize the parameter identifiability in detail and develop diagnostic tools to guide applied researchers when parameters are near non-identifiable boundaries. Furthermore, future study will explore an exponentiated extension of the hybrid Weibull–Exponentiated Rayleigh distribution and assess its ability to improve model fit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O.A. and A.S.O.; methodology, T.O.A. and A.S.O.; software, T.O.A.; validation, T.O.A. and A.S.O.; formal analysis, T.O.A.; investigation, T.O.A.; resources, T.O.A.; data curation, T.O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.O.A.; writing—review and editing, T.O.A. and A.S.O.; visualization, T.O.A. and A.S.O.; supervision, A.S.O.; project administration, A.S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the South African Medical Research Council of grant number SAMRC/UFH/P790 and the APC was funded by the University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Department of Computational Sciences for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDF | Cumulative distribution function |

| PDF | Probability distribution function |

| AIC | Akaike information criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| HQIC | Hannan–Quinn information criterion |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| MLE | Maximum likelihood estimation |

| SE | Standard error |

| MOM | Method of moment |

| HWERD | Hybrid Weibull–Exponetiated Rayleigh Distribution |

| WED | Weibull–Exponentiated distribution |

| EWED | Exponentiated Weibull exponetial distribution |

| EED | Exponential Exponentiated distribution |

| EWRD | Exponential Weibull Rayleigh distribution |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Bladder cancer remission duration dataset (128 patients) [

19].

Table A1.

Bladder cancer remission duration dataset (128 patients) [

19].

| 0.08 | 2.09 | 3.48 | 4.87 | 6.94 | 8.66 | 13.11 | 23.63 |

| 0.20 | 2.23 | 3.52 | 4.98 | 6.97 | 9.02 | 13.29 | 0.40 |

| 2.26 | 3.57 | 5.06 | 7.09 | 9.22 | 13.80 | 25.74 | 0.50 |

| 2.46 | 3.64 | 5.09 | 7.26 | 9.47 | 14.24 | 25.82 | 0.51 |

| 2.54 | 3.70 | 5.17 | 7.28 | 9.74 | 14.76 | 26.31 | 0.81 |

| 2.62 | 3.82 | 5.32 | 7.32 | 10.06 | 14.77 | 32.15 | 2.64 |

| 3.88 | 5.32 | 7.39 | 10.34 | 14.83 | 34.26 | 0.90 | 2.69 |

| 4.18 | 5.34 | 7.59 | 10.66 | 15.96 | 36.66 | 1.05 | 2.69 |

| 4.23 | 5.41 | 7.62 | 10.75 | 16.62 | 43.01 | 1.19 | 2.75 |

| 4.26 | 5.41 | 7.63 | 17.12 | 46.12 | 1.26 | 2.83 | 4.33 |

| 5.49 | 7.66 | 11.25 | 17.14 | 79.05 | 1.35 | 2.87 | 5.62 |

| 7.87 | 11.64 | 17.36 | 1.40 | 3.02 | 4.34 | 5.71 | 7.93 |

| 1.46 | 18.10 | 11.79 | 4.40 | 5.85 | 8.26 | 11.98 | 19.13 |

| 1.76 | 3.25 | 4.50 | 6.25 | 8.37 | 12.02 | 2.02 | 13.31 |

| 4.51 | 6.54 | 8.53 | 12.03 | 20.28 | 2.02 | 3.36 | 12.07 |

| 6.76 | 21.73 | 2.07 | 3.36 | 6.93 | 8.65 | 12.63 | 22.69 |

Table A2.

The breaking stress of carbon fibers dataset [

23].

Table A2.

The breaking stress of carbon fibers dataset [

23].

| 0.39 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.17 | 1.18 |

| 1.22 | 1.25 | 1.36 | 1.41 | 1.47 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 1.59 |

| 1.59 | 1.61 | 1.61 | 1.69 | 1.69 | 1.71 | 1.73 | 1.80 |

| 1.84 | 1.84 | 1.87 | 1.89 | 1.92 | 2.00 | 2.03 | 2.03 |

| 2.05 | 2.12 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 2.35 | 2.38 | 2.41 |

| 2.43 | 2.48 | 2.48 | 2.50 | 2.53 | 2.55 | 2.55 | 2.56 |

| 2.59 | 2.67 | 2.73 | 2.74 | 2.76 | 2.77 | 2.79 | 2.81 |

| 2.81 | 2.82 | 2.83 | 2.85 | 2.87 | 2.88 | 2.93 | 2.95 |

| 2.96 | 2.97 | 2.97 | 3.09 | 3.11 | 3.11 | 3.15 | 3.15 |

| 3.19 | 3.19 | 3.22 | 3.22 | 3.27 | 3.28 | 3.31 | 3.31 |

| 3.33 | 3.39 | 3.39 | 3.51 | 3.56 | 3.60 | 3.65 | 3.68 |

| 3.68 | 3.68 | 3.70 | 3.75 | 4.20 | 4.38 | 4.42 | 4.70 |

| 4.90 | 4.91 | 5.08 | 5.56 | | | | |

References

- Alzaatreh, A.; Lee, C.; Famoye, F. A new method for generating families of distributions with an application to exponential distributions. J. Stat. Distrib. Appl. 2012, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, M.; Lai, C.D.; Zitikis, R. A flexible Weibull extension. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2007, 92, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudholkar, G.S.; Srivastava, D.K. Exponentiated Weibull family for analyzing bathtub failure-rate data. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1993, 42, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbatal, I.; Elgarhy, M.; Kibria, B.M.G. Alpha Power Transformed Weibull-G Family of Distributions: Theory and Applications. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 2021, 20, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Famoye, F.; Olumolade, O. Beta-Weibull distribution: Some properties and applications to censored data. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2007, 6, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.M.; Ortega, E.M.M.; Nadarajah, S. The Kumaraswamy Weibull distribution with application to failure data. J. Frankl. Inst. 2010, 347, 1399–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.O.; Ortega, E.M.M.; Cordeiro, G.M. The beta modified Weibull distribution. Lifetime Data Anal. 2010, 16, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Cui, W.; Du, X. An additive modified Weibull distribution. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2016, 145, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadat, N.; Nagarjuna, V.B.V.; Hassan, A.S.; Elgarhy, M.; Ahmad, H.; Almetwally, E.M. Marshall-Olkin Weibull-Burr XII distribution with application to physics data. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 095325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, S.A.; Elbatal, I.; Alotaibi, N.; Almetwally, E.M.; Okasha, H.M.; Elgharhy, M. Topp–Leone Modified Weibull Model: Theory and Applications to Medical and Engineering Data. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsanya, A.S.; Obalowu, J. On the inferences and applications of Weibull Half-Laplace (exponential) distribution. Reliab. Theory Appl. 2023, 18, 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Elgarhy, M.; Elbatal, I.; Hamedani, G.; Hassan, A. On the exponentiated weibull rayleigh distribution. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2019, 32, 1060–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsanya, A.; Akarawak, E.E.E.; Yahya, W.B. A new quantile estimation method of Weibull Rayleigh distribution. Asian J. Probab. Stat. 2020, 9, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsanya, A.S.; Yahya, W.B.; Mobolaji, A.T.; Iluno, C.; Aderele, O.R.; Ekum, M.I. A New Three-Parameter Weibull Inverse Rayleigh Distribution: Theoretical Development and Applications. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakoban, R.A.; Al-Shehri, A.M. A New Generalization of the Generalized Inverse Rayleigh Distribution with Applications. Symmetry 2021, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilai, M.; Waititu, G.A.; Kibira, W.A.; El-Raouf, M.A.; Abusha, T.A. A new versatile modification of the Rayleigh distribution for modeling COVID-19 mortality rates. Results Phys. 2022, 35, 105260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galton, F. Natural Inheritance; Macmillan: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Moors, J.J.A. A Quantile Alternative for Kurtosis. Statistician 1988, 37, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.T.; Wang, J. Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 476. [Google Scholar]

- Klakattawi, H.S. Survival analysis of cancer patients using a new extended Weibull distribution. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaji, L.; Alghamdi, A.S. The exponentiated new exponential-gamma distribution: Properties and application. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.; Asim, S.; Farooq, M.; Khan, S.A.; Manzoor, S. A Gull Alpha Power Weibull distribution with applications to real and simulated data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, M.D.; Padgett, W.J. A Bootstrap Control Chart for Weibull Percentiles. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2006, 22, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyian, K.E.; Ezerioha, E.I.; Ogbonna, J.C.; Daniels, M.E. New Generalized Nadarajah Haghighi Distribution: Characterization and Applications. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Fu, J.; Yincai, T. Bayesian Estimation of Gumbel Type-II Distribution. Data Sci. J. 2013, 12, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makubate, B.; Dingalo, N.; Oluyede, B.O.; Fagbamigbe, A.F. The Exponentiated Burr XII Weibull Distribution: Model, Properties and Applications. J. Data Sci. 2018, 16, 431–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |