MPC-Coder: A Dual-Knowledge Enhanced Multi-Agent System with Closed-Loop Verification for PLC Code Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. LLM-Based Code Generation

2.2. Knowledge-Enhanced Code Generation

2.3. Multi-Agent Collaboration and Verification Mechanisms

2.4. Major Limitations of Existing Research

3. Methodology

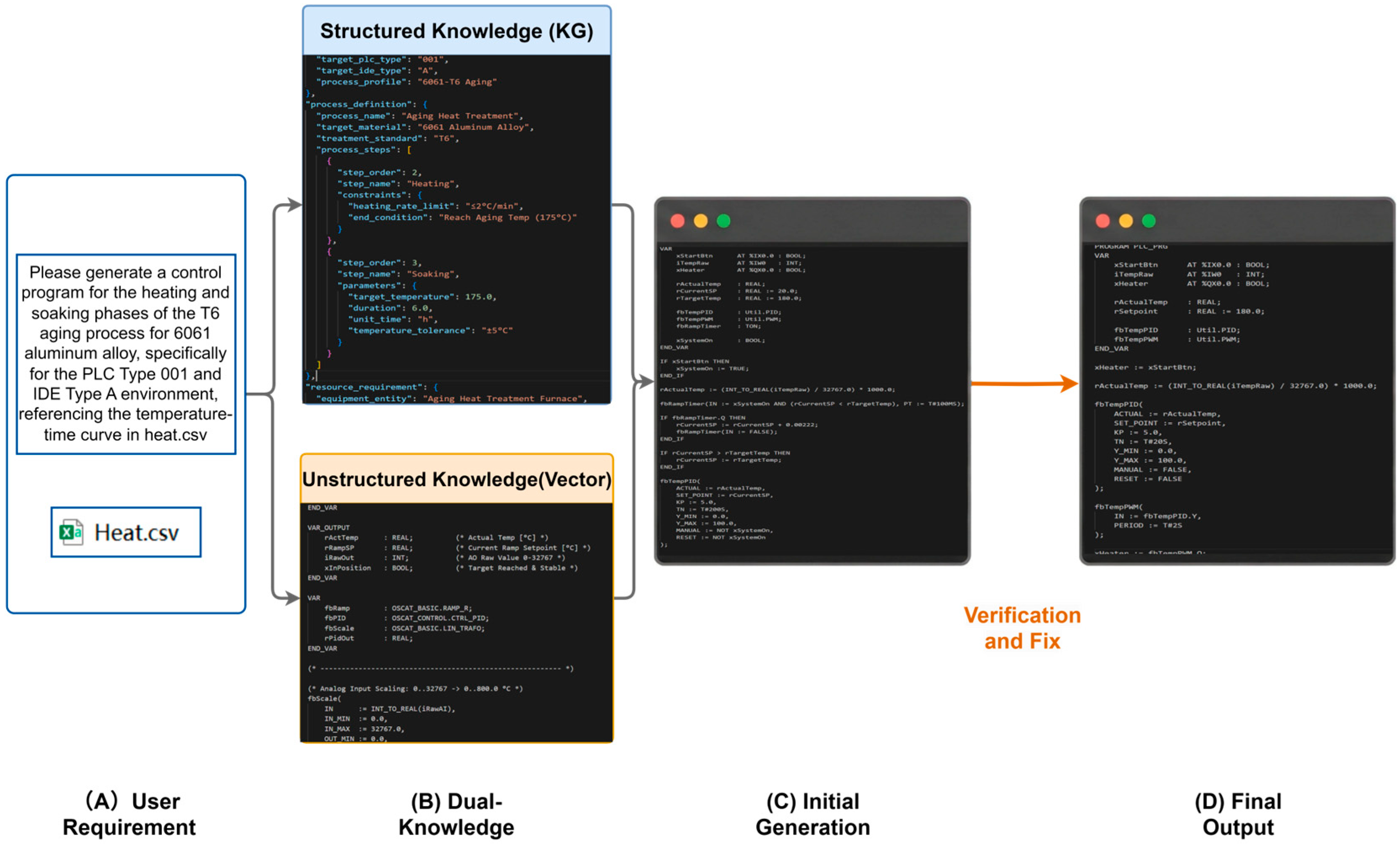

3.1. Overall System Architecture

3.2. Dual-Knowledge Architecture

3.2.1. Knowledge Graph Construction

3.2.2. Vector Database Construction

3.2.3. Hybrid Retrieval Strategy

3.3. Multi-Agent Collaboration Mechanism

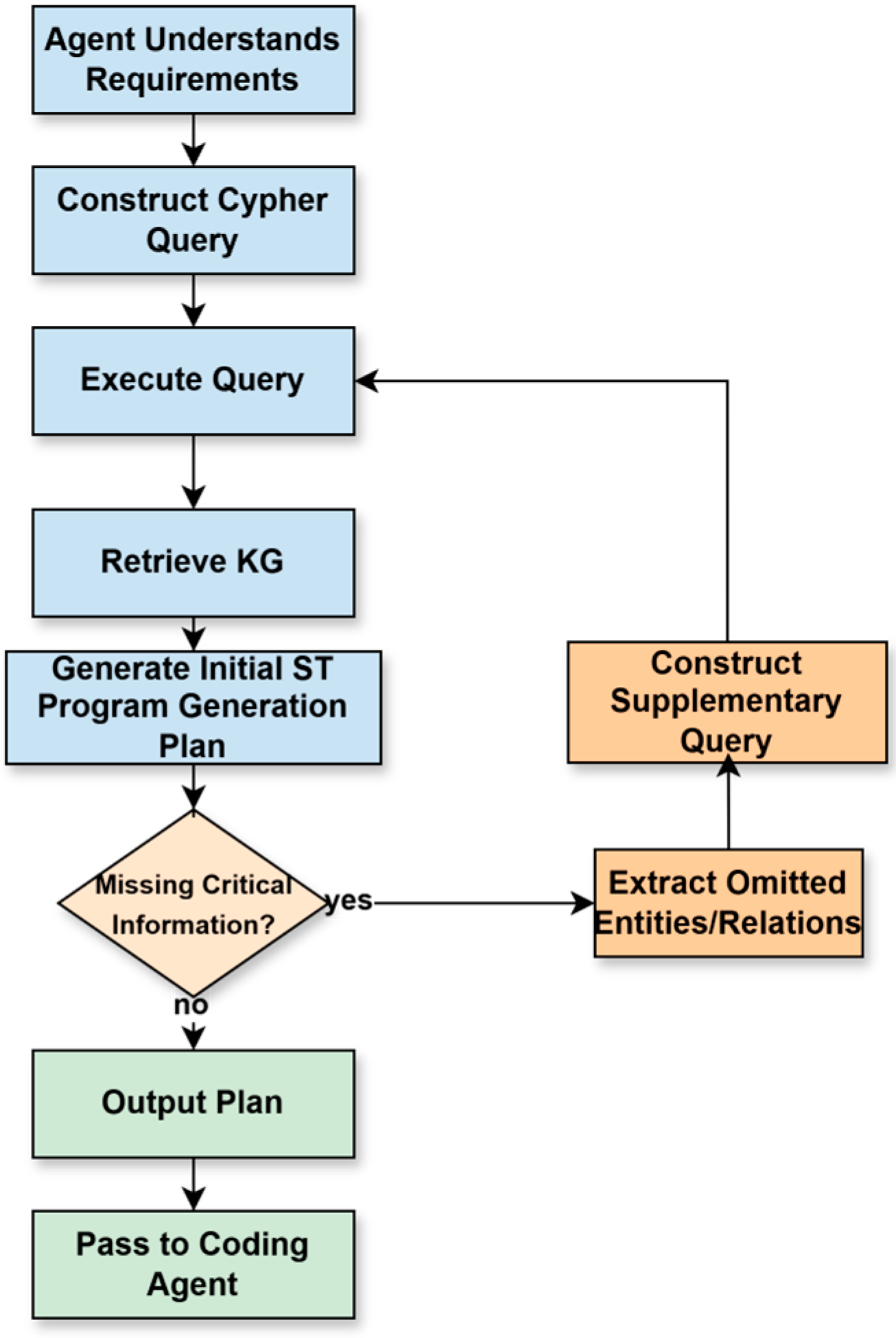

3.3.1. Forward Generation Workflow

3.3.2. Closed-Loop Verification and Repair

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Experimental Environment

4.1.2. Evaluation Dataset

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

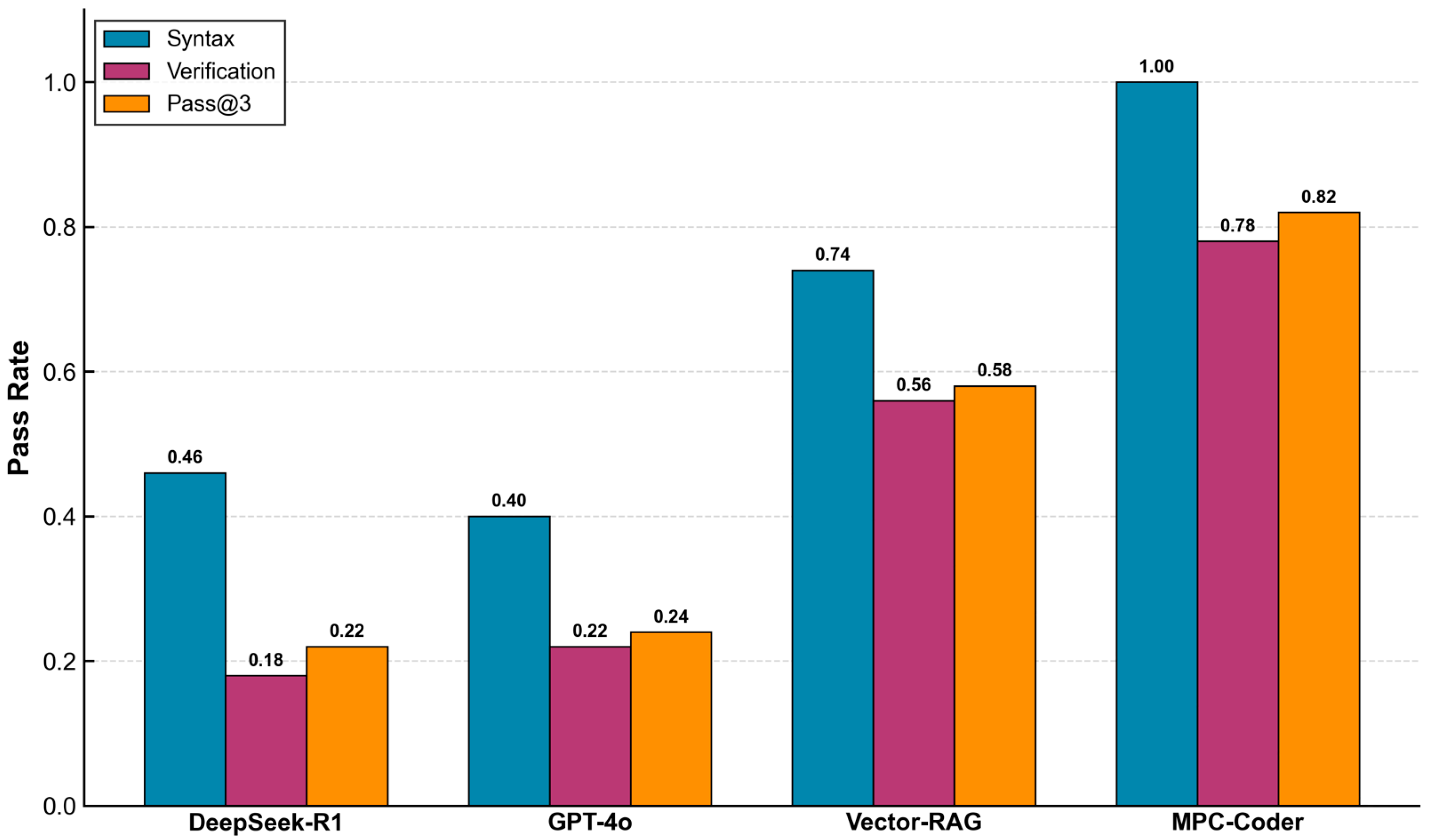

4.2. Overall Performance Comparison

4.2.1. Comparative Methods

4.2.2. Comparison Results

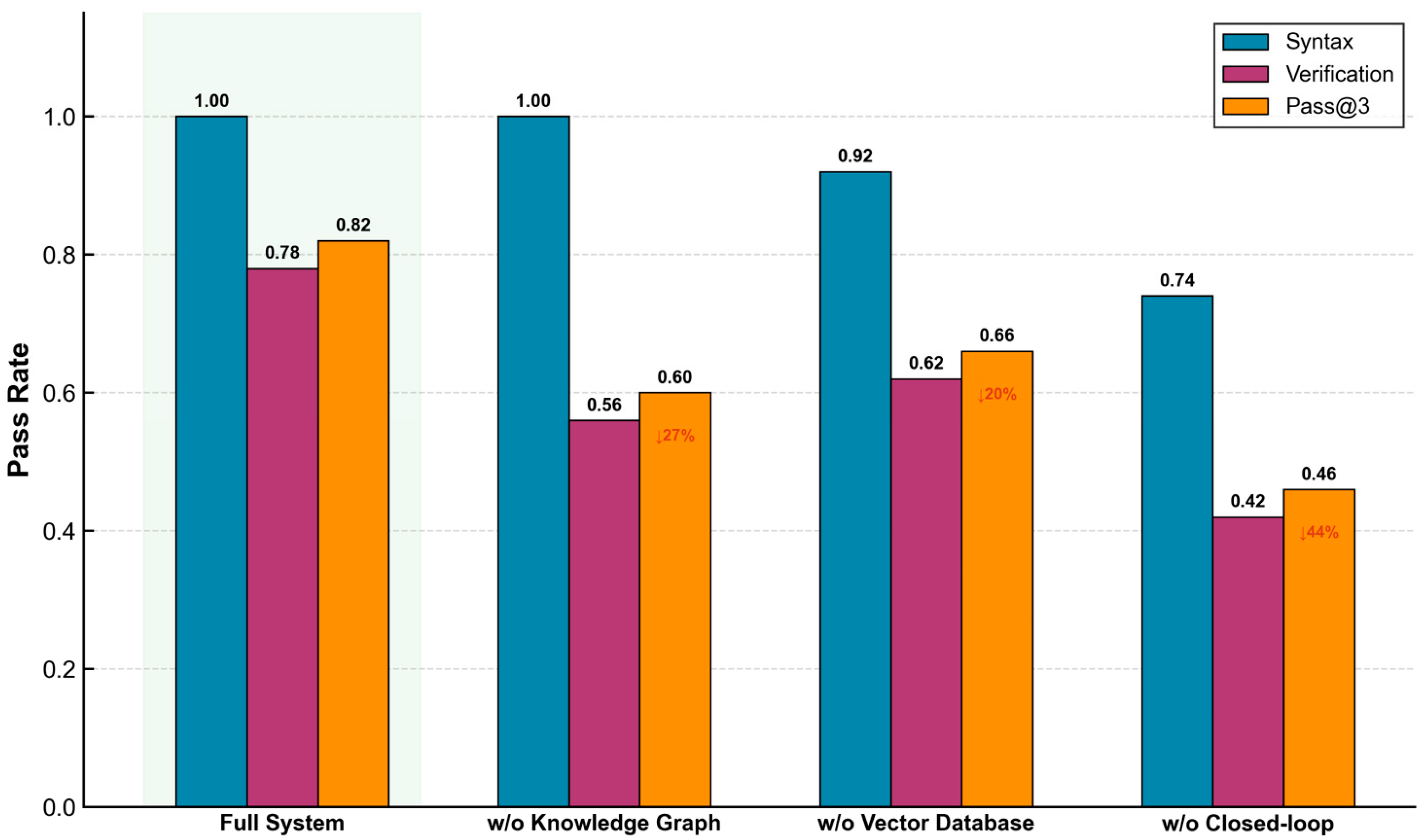

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. Ablation Settings

4.3.2. Ablation Results

4.3.3. Analysis of Module Contributions

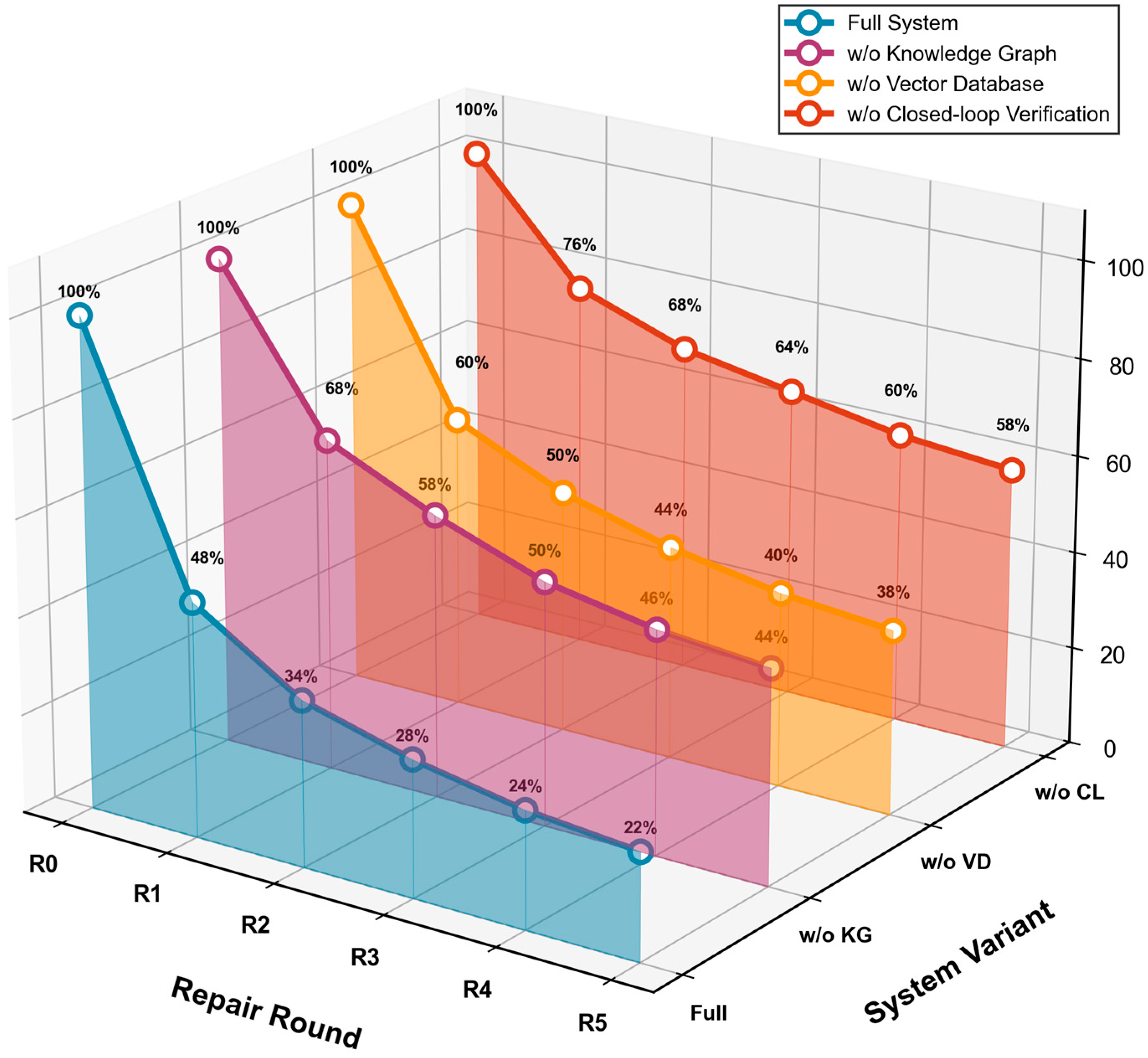

4.4. Convergence Analysis

4.4.1. Valuation Metric

4.4.2. Iteration Trajectory

4.4.3. Convergence Behavior Analysis

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Research Summary

5.2. Main Conclusions

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, J.; Li, P.G.; Zhou, Y.H.; Wang, B.C.; Zang, J.Y.; Meng, L. Toward New-Generation Intelligent Manufacturing. Engineering 2018, 4, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y.H.; Wang, B.C.; Zang, J.Y. Human-Cyber-Physical Systems (HCPSs) in the Context of New-Generation Intelligent Manufacturing. Engineering 2019, 5, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61131-3:2013; Programmable Controllers—Part 3: Programming Languages. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Tiegelkamp, M.; John, K.-H. IEC 61131-3: Programming Industrial Automation Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 166. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, E.G.; Bryla, E.J. Software Architecture and Framework for Programmable Logic Controllers: A Case Study and Suggestions for Research. Machines 2016, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.W.; Vyatkin, V. A Case Study on Migration from IEC 61131 PLC to IEC 61499 Function Block Control. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Conference on Industrial Informatics, Cardiff, UK, 23–26 June 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Renard, D.; Saddem, R.; Annebicque, D.; Riera, B. From Sensors to Digital Twins toward an Iterative Approach for Existing Manufacturing Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Fine-Tune LLMs for PLC Code Security: An Information-Theoretic Analysis. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.A.; Prabha, S.; Cabello, C.A.G.; Genovese, A.; Collaco, B.; Wood, N.; London, J.; Bagaria, S.; Tao, C.; Forte, A.J. The Development and Evaluation of a Retrieval-Augmented Generation Large Language Model Virtual Assistant for Postoperative Instructions. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizi, M.K.Z.; Suh, Y. Design and Performance Evaluation of LLM-Based RAG Pipelines for Chatbot Services in International Student Admissions. Electronics 2025, 14, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.; Dharmaji, R.; Moghaddas, Y.; Araya, G.Q.; Ogundare, O.; Al Faruque, M.A.; Assoc Computing, M. LLM4PLC: Harnessing Large Language Models for Verifiable Programming of PLCs in Industrial Control Systems. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 46th International Conference on Software Engineering—Software Engineering in Practice (ICSE-SEIP), Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Gu, M.; Song, X.Y.; Wan, H. Formal Specification and Code Generation of Programable Logic Controllers. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Conference on Engineering Complex Computer Systems, Potsdam, Germany, 2–4 June 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov, D.; Schütz, D.; Ulewicz, S.; Vogel-Heuser, B. Towards Industrial Application of Model-driven Platform-independent PLC Programming Using UML. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference of the IEEE-Industrial-Electronics-Society (IECON), Dallas, TX, USA, 29 October–1 November 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 2638–2644. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, D.; Park, C.M.; Park, S.C.; Wang, G.N. Auto-Generation of IEC Standard PLC Code Using t-MPSG. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2009, 7, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartjes, L.; van Beek, D.A.; Fokkink, W.J.; van Eekelen, J. Model-based design of supervisory controllers for baggage handling systems. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2017, 78, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, M.; Zoitl, A. Automated Code Generation for Programmable Logic Controllers based on Knowledge Acquisition from Engineering Artifacts: Concept and Case Study. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), AGH Univ Sci & Technol, Krakow, Poland, 17–21 September 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prenzel, L.; Provost, J. PLC Implementation of Symbolic, Modular Supervisory Controllers. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovskyi, Y.; Kennel, M.; Schmucker, U. Template-Based Generation of PLC Software from Plant Models Using Graph Representation. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice (M2VIP), Stuttgart, Germany, 20–22 November 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Julius, R.; Trenner, T.; Neidig, J.; Fay, A. A model-driven approach for transforming GRAFCET specification into PLC code including hierarchical structures. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.; Huang, C.H.; Ruess, H.; Stattelmann, S. G4LTL-ST: Automatic Generation of PLC Programs. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Computer Aided Verification (CAV) Held as Part of the Vienna Summer of Logic (VSL), Vienna Univ Technol, Vienna, Austria, 18–22 July 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 541–549. [Google Scholar]

- Svyatkovskiy, A.; Deng, S.K.; Fu, S.Y.; Sundaresan, N. IntelliCode Compose: Code Generation using Transformer. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE), Virtual, 8–13 November 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1433–1443. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.; Zhang, J.X.; Pfeiffer, J.; Wortmann, A.; Wiesmayr, B. Generating PLC Code with Universal Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 29th Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation-ETFA-Annual, Padova, Italy, 10–13 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Haag, A.; Fuchs, B.; Kacan, A.; Lohse, O.; Ieee Computer, S.O.C. Training LLMs for Generating IEC 61131-3 Structured Text with Online Feedback. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Workshop on Large Language Models for Code-LLM4Code, Ottawa, Canada, 3 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Koziolek, H.; Grüner, S.; Hark, R.; Ashiwal, V.; Linsbauer, S.; Eskandani, N. LLM-based and Retrieval-Augmented Control Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Large Language Models for Code (LLM4Code), Lisbon, Portugal, 20 April 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Wu, X.D. Give us the Facts: Enhancing Large Language Models with Knowledge Graphs for Fact-Aware Language Modeling. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 3091–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.W.; Liu, L.F.; Xi, J.Z.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, X.L. KLR-KGC: Knowledge-Guided LLM Reasoning for Knowledge Graph Completion. Electronics 2024, 13, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.M.; Qin, F.W.; Sun, D.F.; Wu, H.F. A multi-facets ontology matching approach for generating PLC domain knowledge graphs. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 10929–10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.L.; Zhang, N.; Yu, B.; Duan, Z.H. Generating Java code pairing with ChatGPT. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2024, 1021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.X.; Cai, L.W.; Zhang, Y.W.; Xin, X.Q.; Jiang, B.; Qi, L. Intelligent Q&A System for Welding Processes Based on a Symmetric KG-DB Hybrid-RAG Strategy. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Ali, M.E.; Parvez, M.R. MapCoder: Multi-Agent Code Generation for Competitive Problem Solving. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association-for-Computational-Linguistics (ACL)/Student Research Workshop (SRW), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 4912–4944. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.Y.; Huang, S.B.; Wei, C.; Wang, R. Collaboration between intelligent agents and large language models: A novel approach for enhancing code generation capability. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 269, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Jiang, X.; Jin, Z.; Li, G. Self-Collaboration Code Generation via ChatGPT. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2024, 33, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.C.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Shi, X.J.; Jint, Z. CODEAGENT: Enhancing Code Generation with Tool-Integrated Agent Systems for Real-World Repo-level Coding Challenges. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association-for-Computational-Linguistics (ACL)/Student Research Workshop (SRW), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 13643–13658. [Google Scholar]

- Koziolek, H.; Ashiwal, V.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Chandrika, K.R. Automated Control Logic Test Case Generation using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 29th Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation-ETFA-Annual, Padova, Italy, 10–13 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.G.; Shi, J.Q.; Su, T.; Lu, Z.Y.; Hao, L.; Huang, Y.H. Automated test generation for IEC 61131-3 ST programs via dynamic symbolic execution. Sci. Comput. Program. 2021, 206, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, X.; Mavridou, A.; Katis, A.; Adiego, B.F. Verifying PLC Programs via Monitors: Extending the Integration of FRET and PLCverif. In Proceedings of the 16th International Symposium on NASA Formal Methods (NFM), NASA Ames Res Ctr, Moffett Field, CA, USA, 4–6 June 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 427–435. [Google Scholar]

- Cavada, R.; Cimatti, A.; Dorigatti, M.; Griggio, A.; Mariotti, A.; Micheli, A.; Mover, S.; Roveri, M.; Tonetta, S. The NUXMV Symbolic Model Checker. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Computer Aided Verification (CAV) Held as Part of the Vienna Summer of Logic (VSL), Vienna Univ Technol, Vienna, Austria, 18–22 July 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wang, J.Y.; Poskitt, C.M.; Chen, X.X.; Sun, J.; Cheng, P. K-ST: A Formal Executable Semantics of the Structured Text Language for PLCs. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2023, 49, 4796–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Kong, Y.; Chang, T.T.; Liao, X.; Ma, Y.W.; Du, Y. High-Throughput Computing Assisted by Knowledge Graph to Study the Correlation between Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 6XXX Aluminum Alloy. Materials 2022, 15, 5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trelles, E.G.; Schweizer, C.; Thomas, A.; von Hartrott, P.; Janka-Ramm, M. Digitalizing Material Knowledge: A Practical Framework for Ontology-Driven Knowledge Graphs in Process Chains. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liang, J.X.; Li, C.L.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.Y.; Ji, Z.Y. Construction of a Machining Process Knowledge Graph and Its Application in Process Route Recommendation. Electronics 2025, 14, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMS2770R; Heat Treatment of Wrought Aluminum Alloy Parts. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020.

| Category | Item | Specification/Version |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | CPU | Intel Core i9-14900K |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090D (24 GB) | |

| Memory | 64 GB DDR5 | |

| Storage | 2 TB NVMe SSD | |

| Software | Operating System | Ubuntu 22.04.4 LTS |

| Programming Language | Python 3.10.12 | |

| Framework | LangChain 0.1.0 | |

| Knowledge Base | Graph Database | Neo4j Community 5.15.0 |

| Vector Database | ChromaDB 0.6.3 | |

| Verification Tools | Compiler | ruSTy (https://github.com/PLC-lang/rusty, accessed on 20 January 2026) |

| Model Checking | nuXmv (Fondazione Bruno Kessler, Trento, Italy)/PLCverif (CERN, Geneva, Switzerland) |

| Method | Syntactic Correctness (%) | Functional Consistency (%) | Pass@3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek-R1 | 46 | 18 | 22 |

| GPT-4o | 40 | 22 | 24 |

| Vector-RAG | 74 | 56 | 58 |

| MPC-Coder | 100 | 78 | 82 |

| System Variant | Syntactic Correctness (%) | Functional Consistency (%) | Pass@3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full System | 100 | 78 | 82 |

| w/o Knowledge Graph | 100 | 56 | 60 |

| w/o Vector Database | 92 | 62 | 66 |

| w/o Closed-Loop Verification | 74 | 42 | 46 |

| Category | Definition | Initial | Final |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1: Missing Input Validation | Unchecked parameter boundaries | 7 | 2 |

| E2: Insecure State Machines | Bypassed interlocks or illegal transitions | 9 | 5 |

| E3: Timing/Control Flow Errors | Race conditions or sequencing issues | 5 | 4 |

| E4: Duplicate Writes | Conflicting output assignments in one cycle | 4 | 0 |

| System Class | Constraint Enforcement | Logic Repair | Functional Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Koziolek et al. [24] | Low (Probabilistic) | None (Open-loop) | 56% (Vector-RAG) |

| LLM4PLC [11] | Low (Probabilistic) | High (Formal Verify) | 56% (w/o KG) |

| MPC-Coder (Ours) | High (KG-based) | High (Formal Verify) | 78% (Full System) |

| System Variant | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full System | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| w/o Knowledge Graph | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.44 |

| w/o Vector Database | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.38 |

| w/o Closed-Loop Verification | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Xia, W.; Zhao, B.; Yuan, T.; Yu, X. MPC-Coder: A Dual-Knowledge Enhanced Multi-Agent System with Closed-Loop Verification for PLC Code Generation. Symmetry 2026, 18, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020248

Zhang Y, Xia W, Zhao B, Yuan T, Yu X. MPC-Coder: A Dual-Knowledge Enhanced Multi-Agent System with Closed-Loop Verification for PLC Code Generation. Symmetry. 2026; 18(2):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020248

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yinggang, Weiyi Xia, Ben Zhao, Tongwen Yuan, and Xianchuan Yu. 2026. "MPC-Coder: A Dual-Knowledge Enhanced Multi-Agent System with Closed-Loop Verification for PLC Code Generation" Symmetry 18, no. 2: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020248

APA StyleZhang, Y., Xia, W., Zhao, B., Yuan, T., & Yu, X. (2026). MPC-Coder: A Dual-Knowledge Enhanced Multi-Agent System with Closed-Loop Verification for PLC Code Generation. Symmetry, 18(2), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18020248