Bayesian-Optimized Explainable AI for CKD Risk Stratification: A Dual-Validated Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Preliminary

3.1. Data Overview

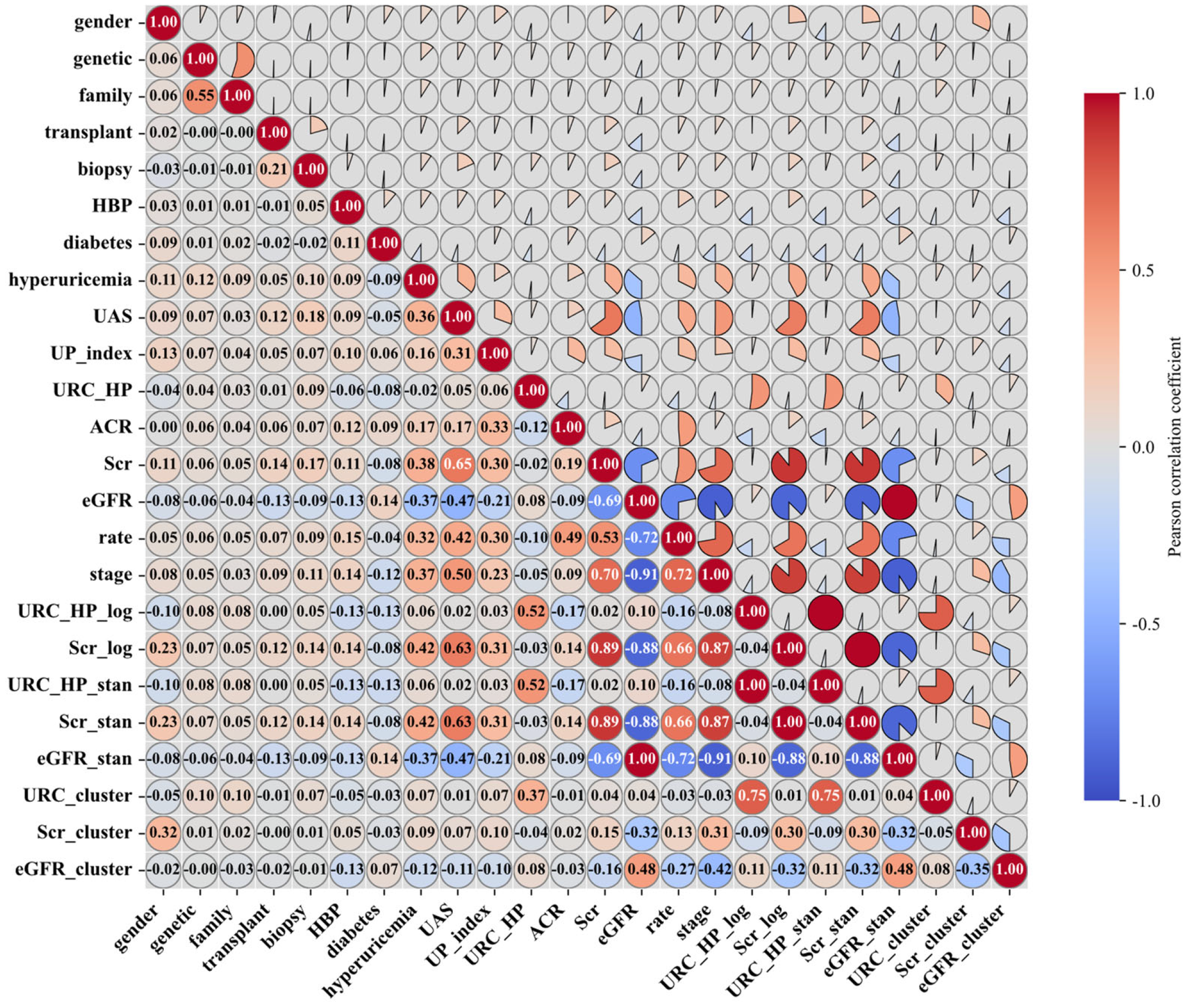

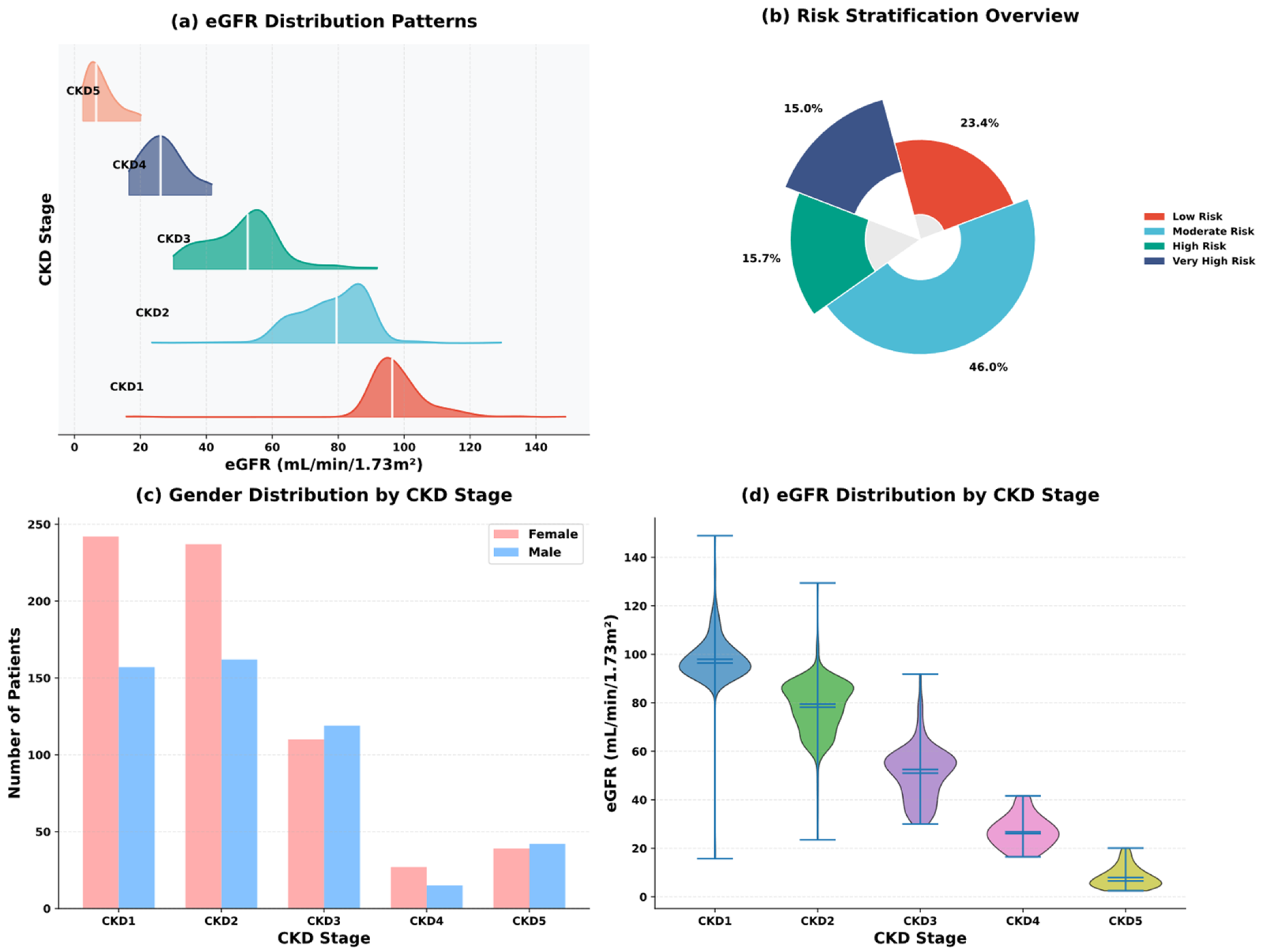

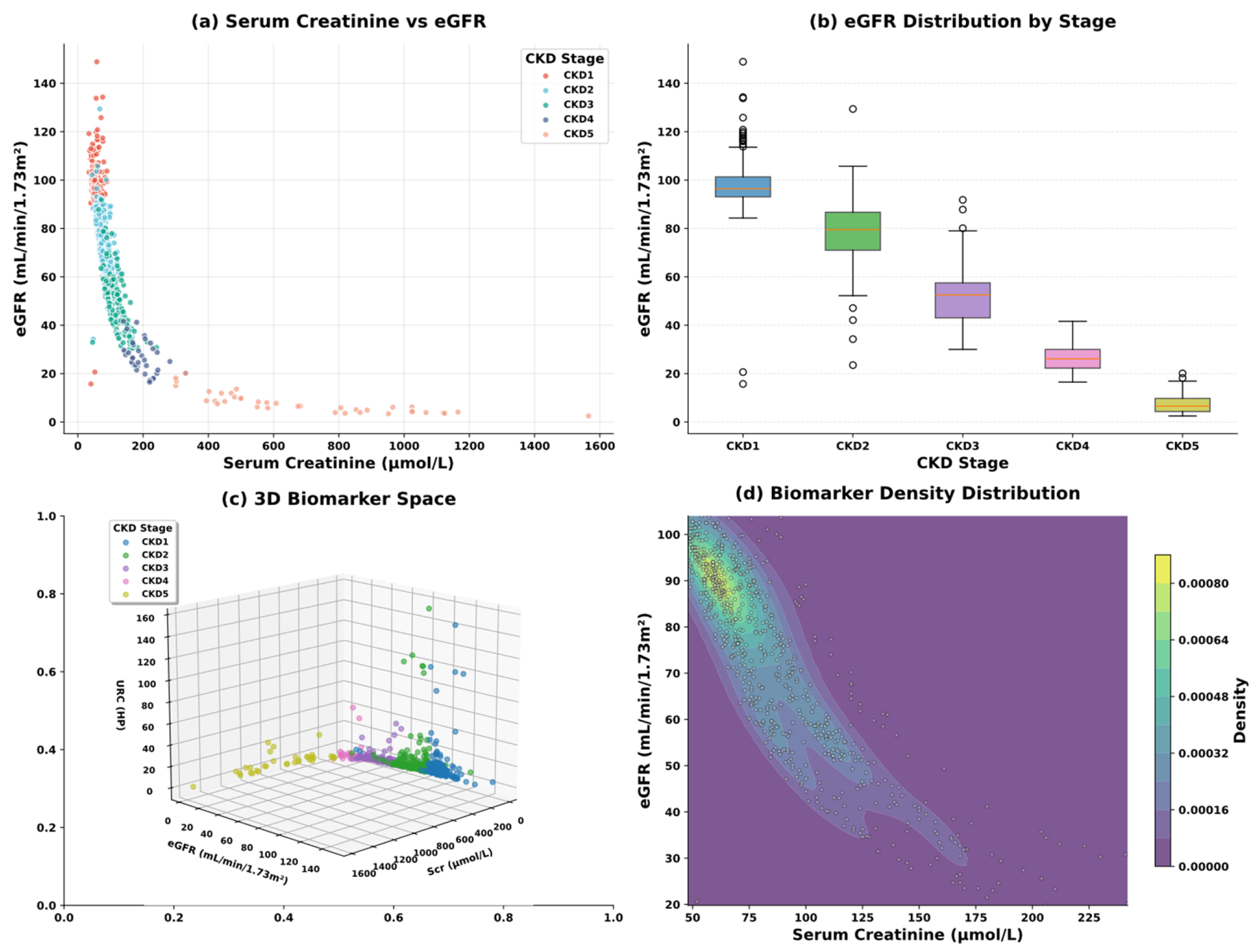

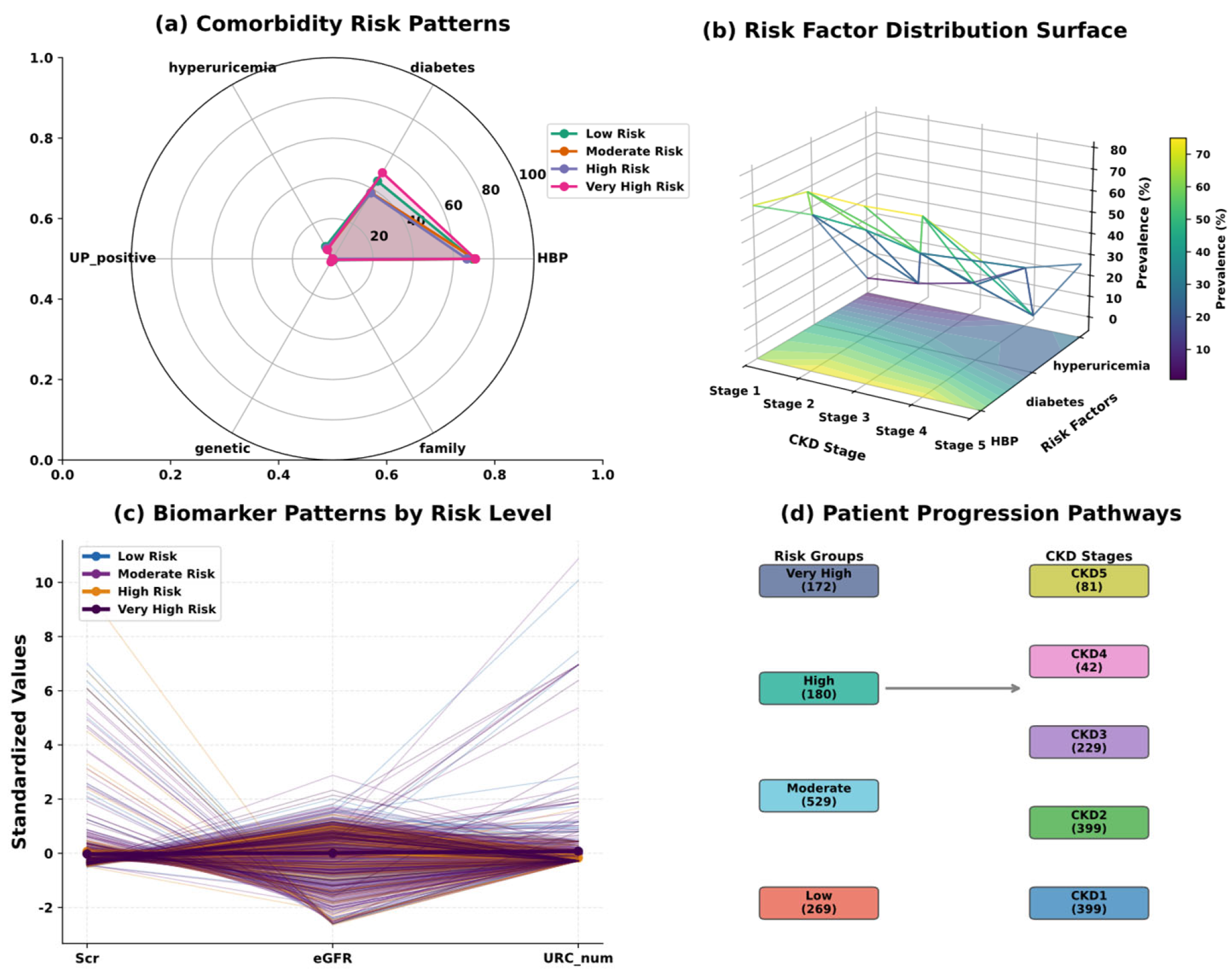

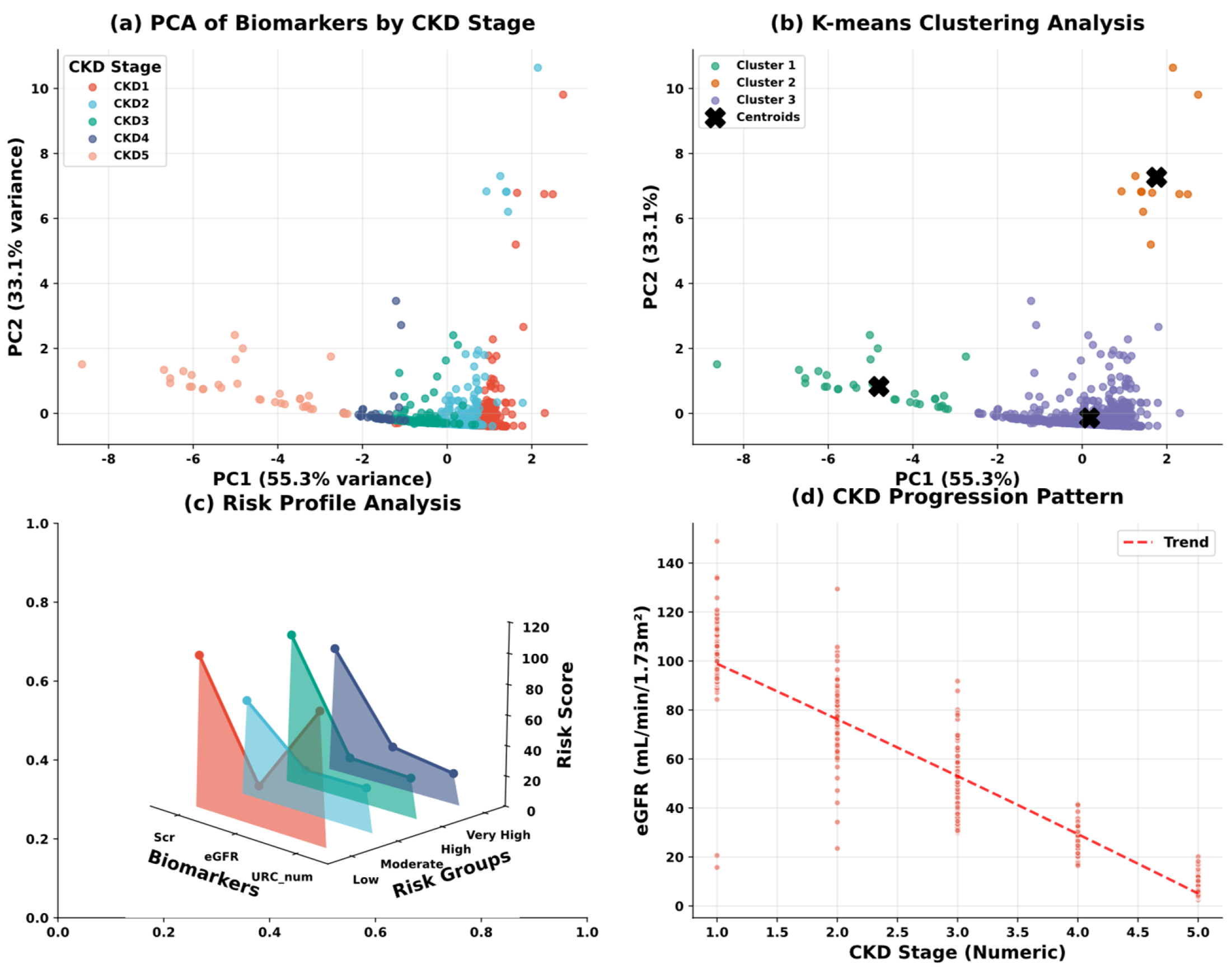

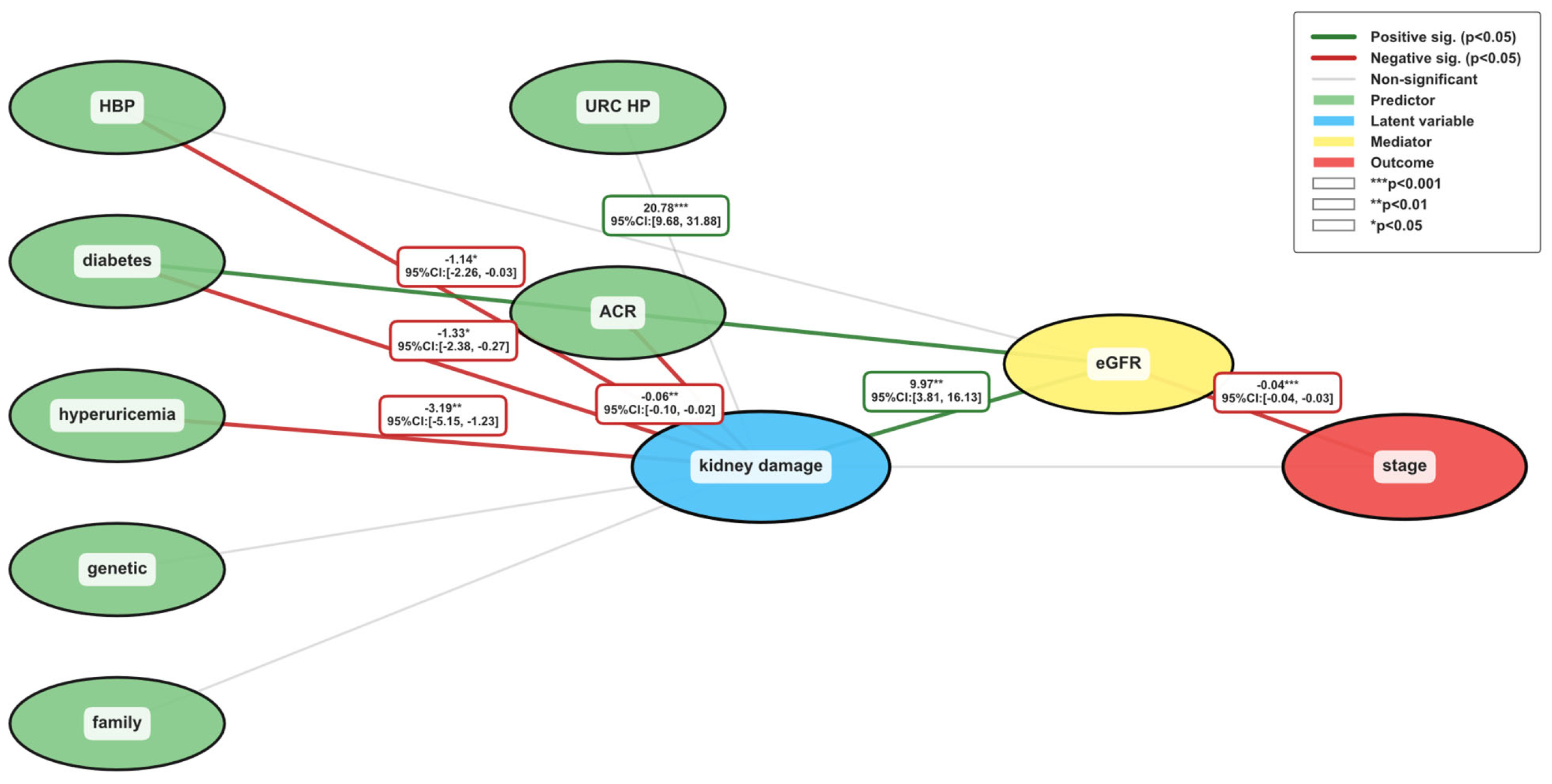

3.2. Exploratory Data Analysis

3.3. Data Processing

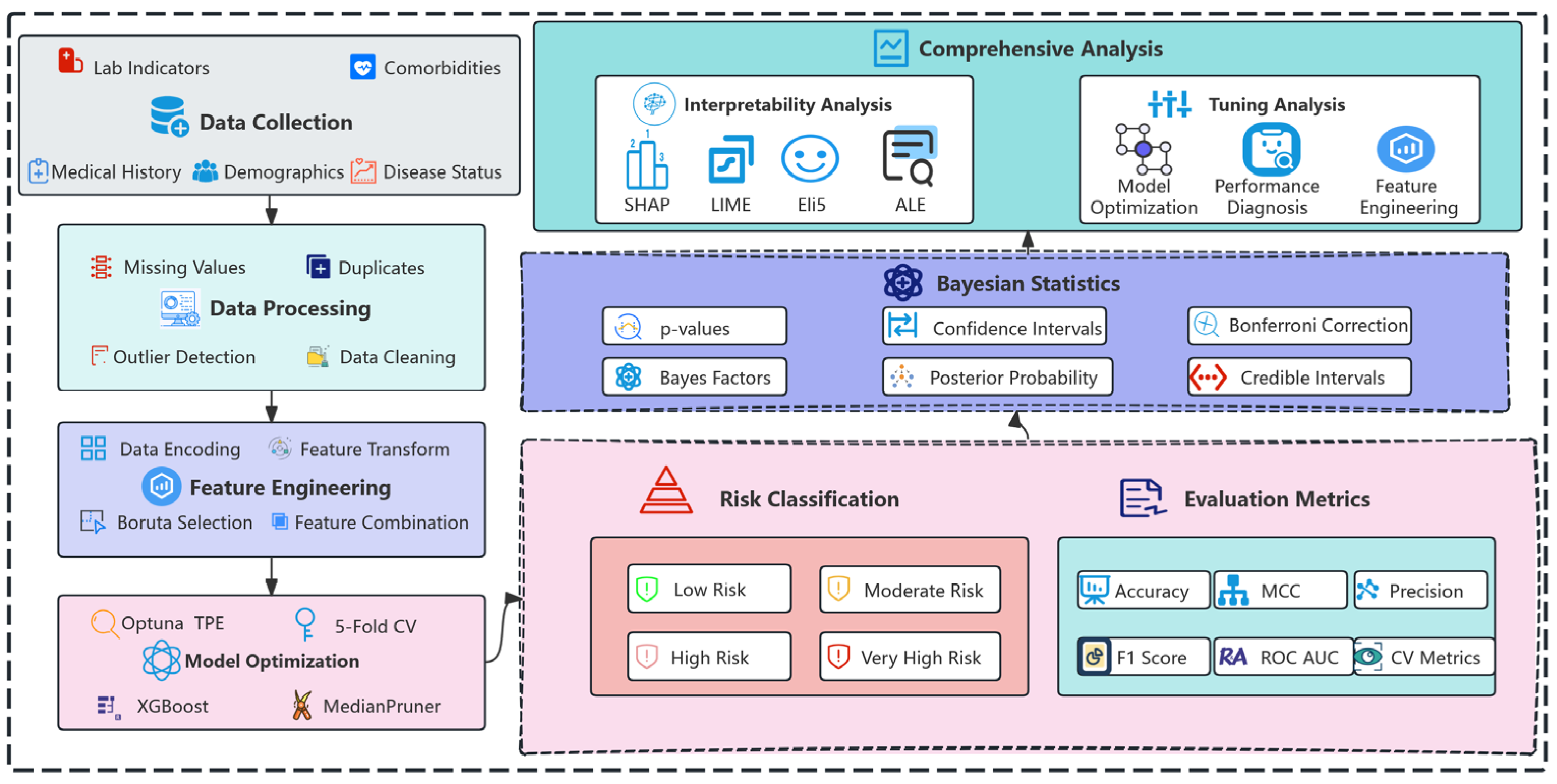

4. Methodology

4.1. XGBoost

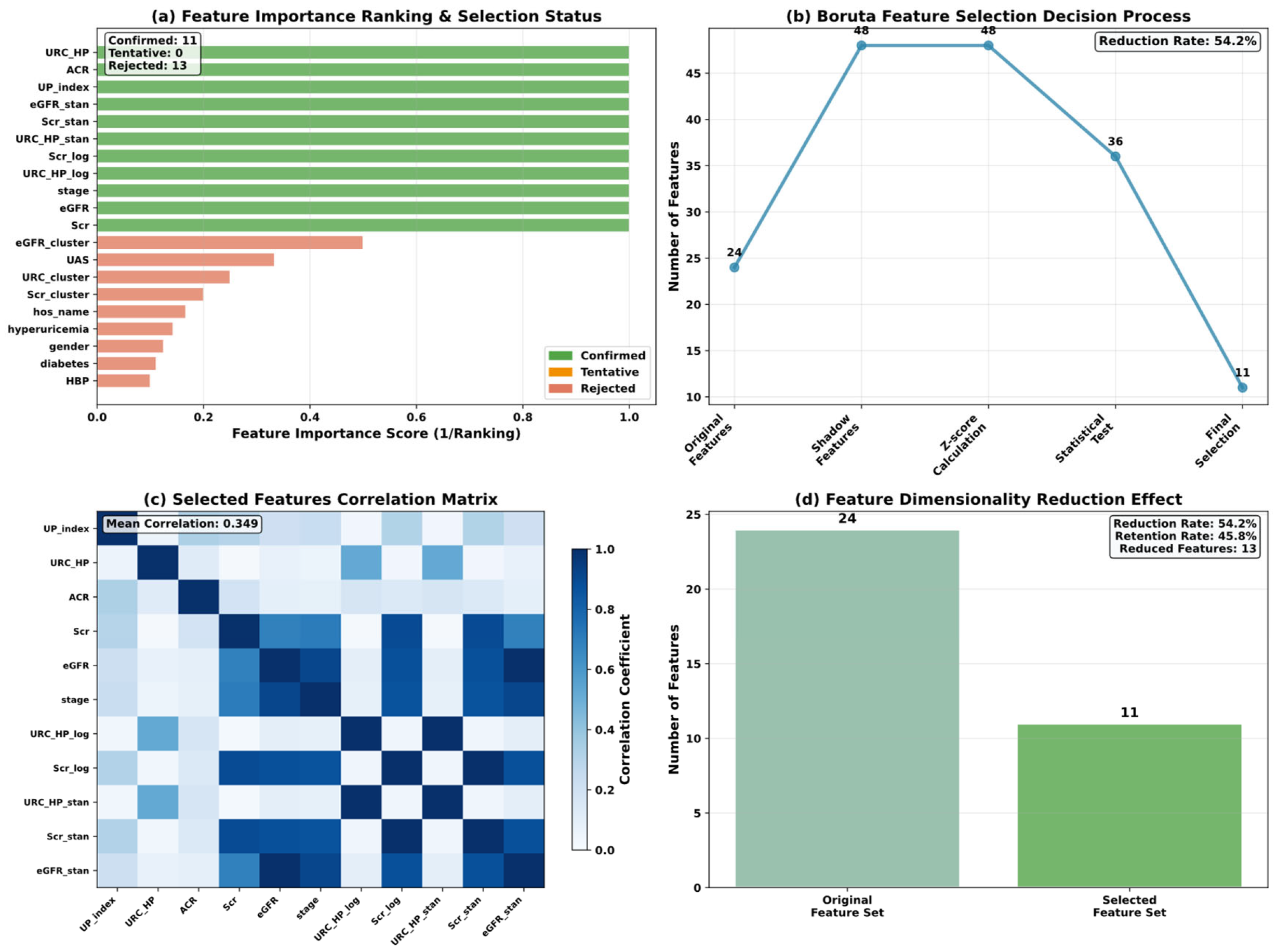

4.2. Boruta

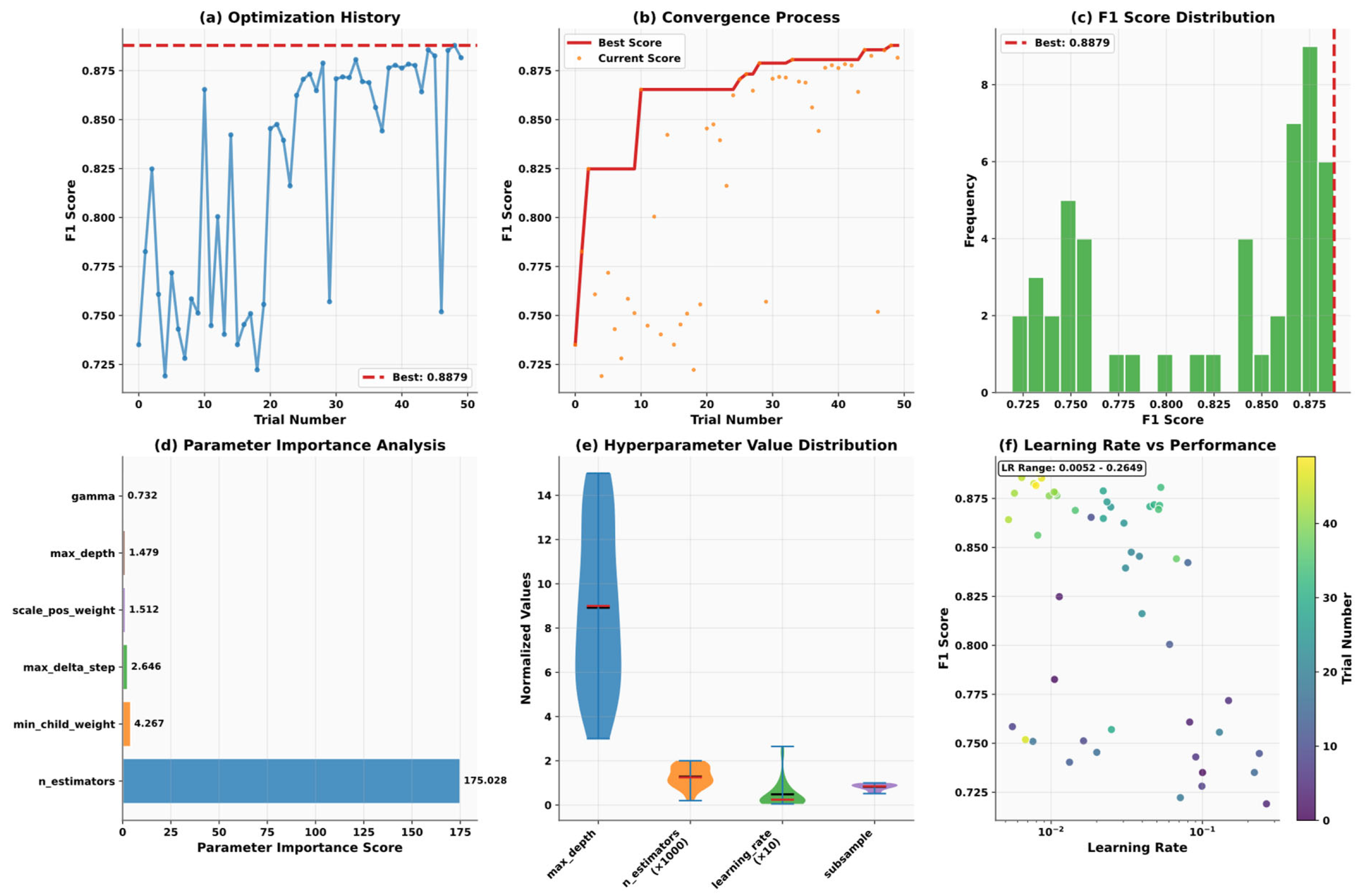

4.3. Optuna

| Algorithm 1: Tree-structured Parzen Estimator | |

| 1: | |

| 2: | do |

| 3: | Sort by objective values |

| 4: | |

| 5: | |

| 6: | |

| 7: | *Acquisition function* |

| 8: | |

| 9: | |

| 10: | end for |

| 11: | |

4.4. Model Validation Strategy

5. Experiment

5.1. Experimental Configuration and Setup

5.2. Performance Metrics

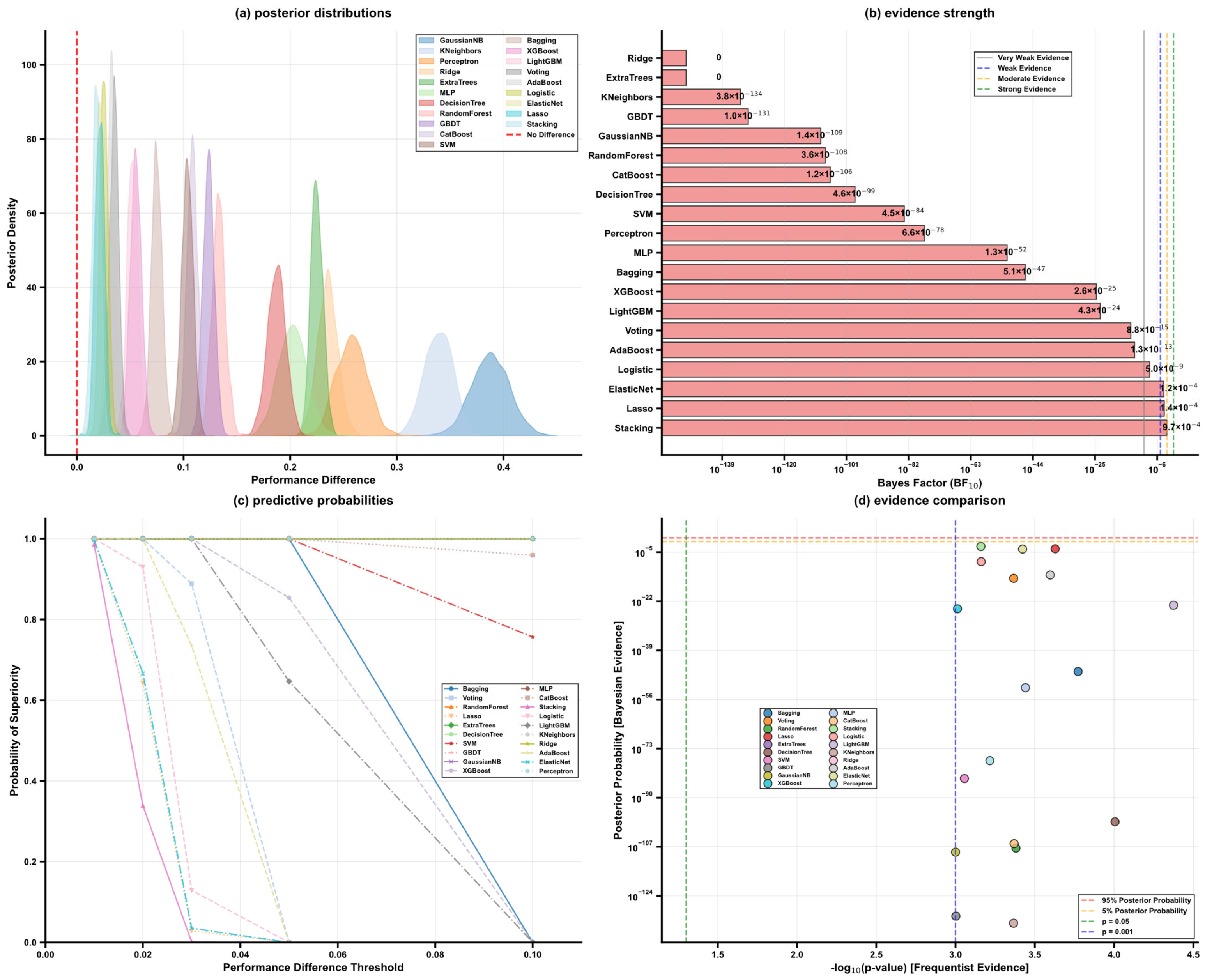

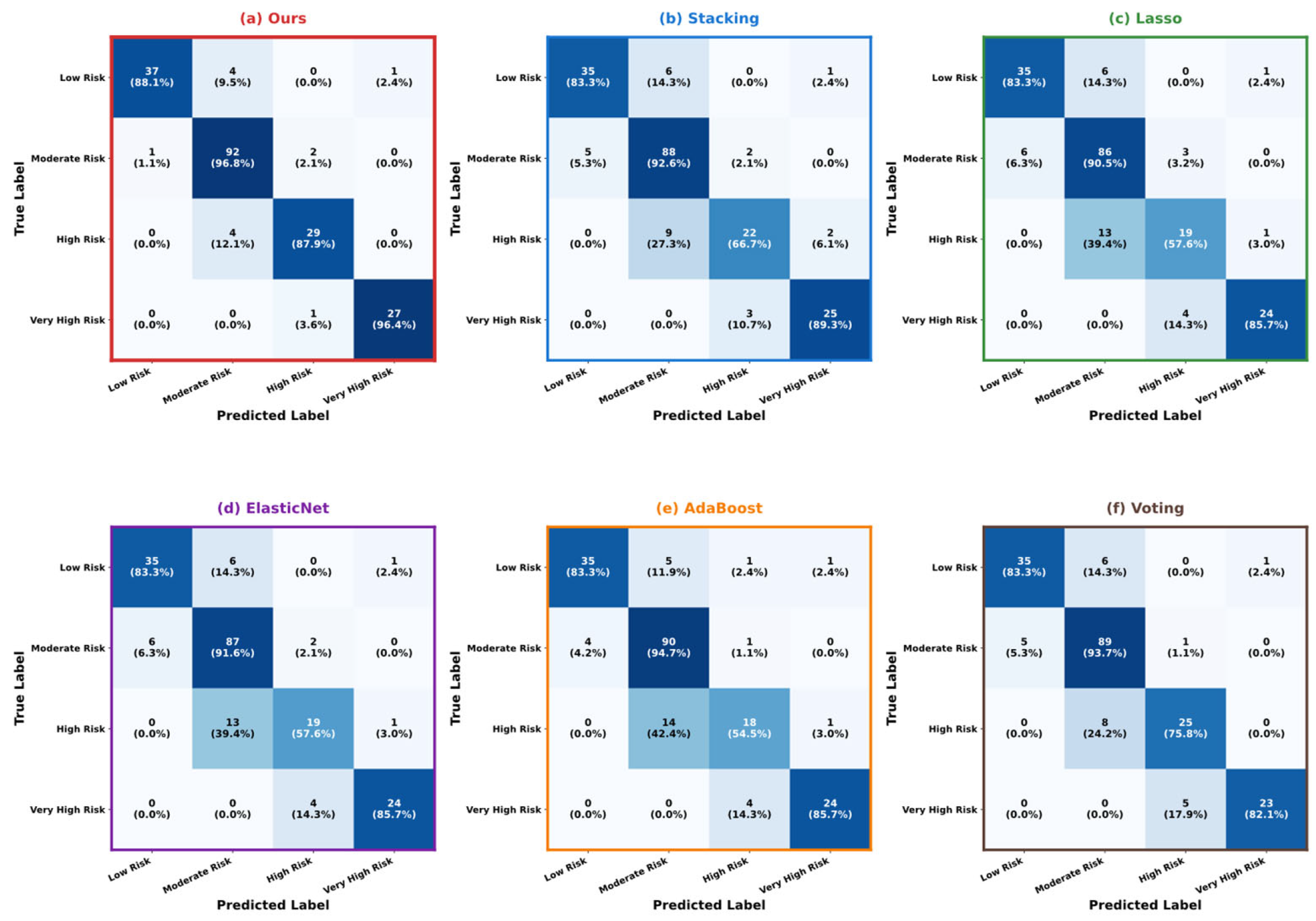

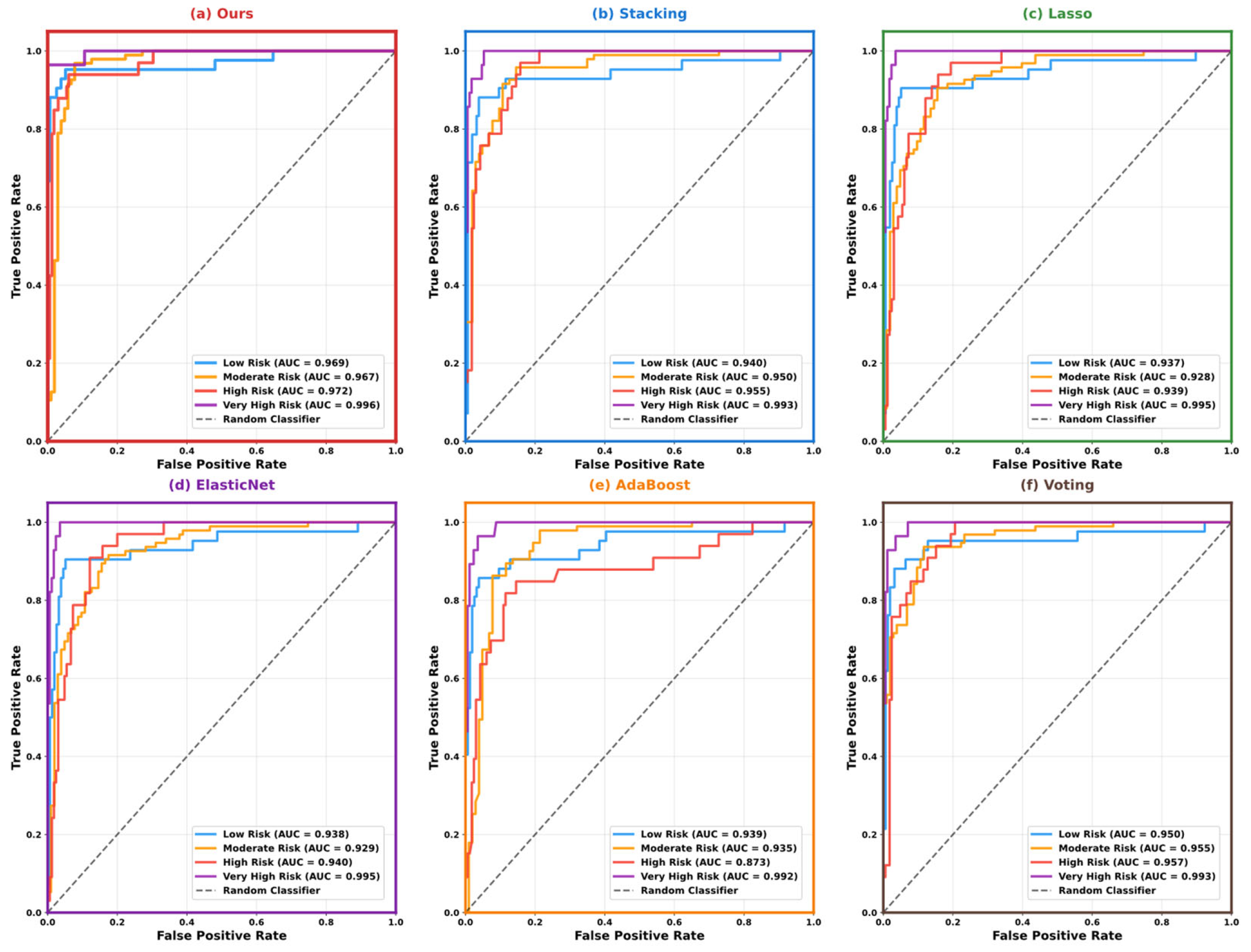

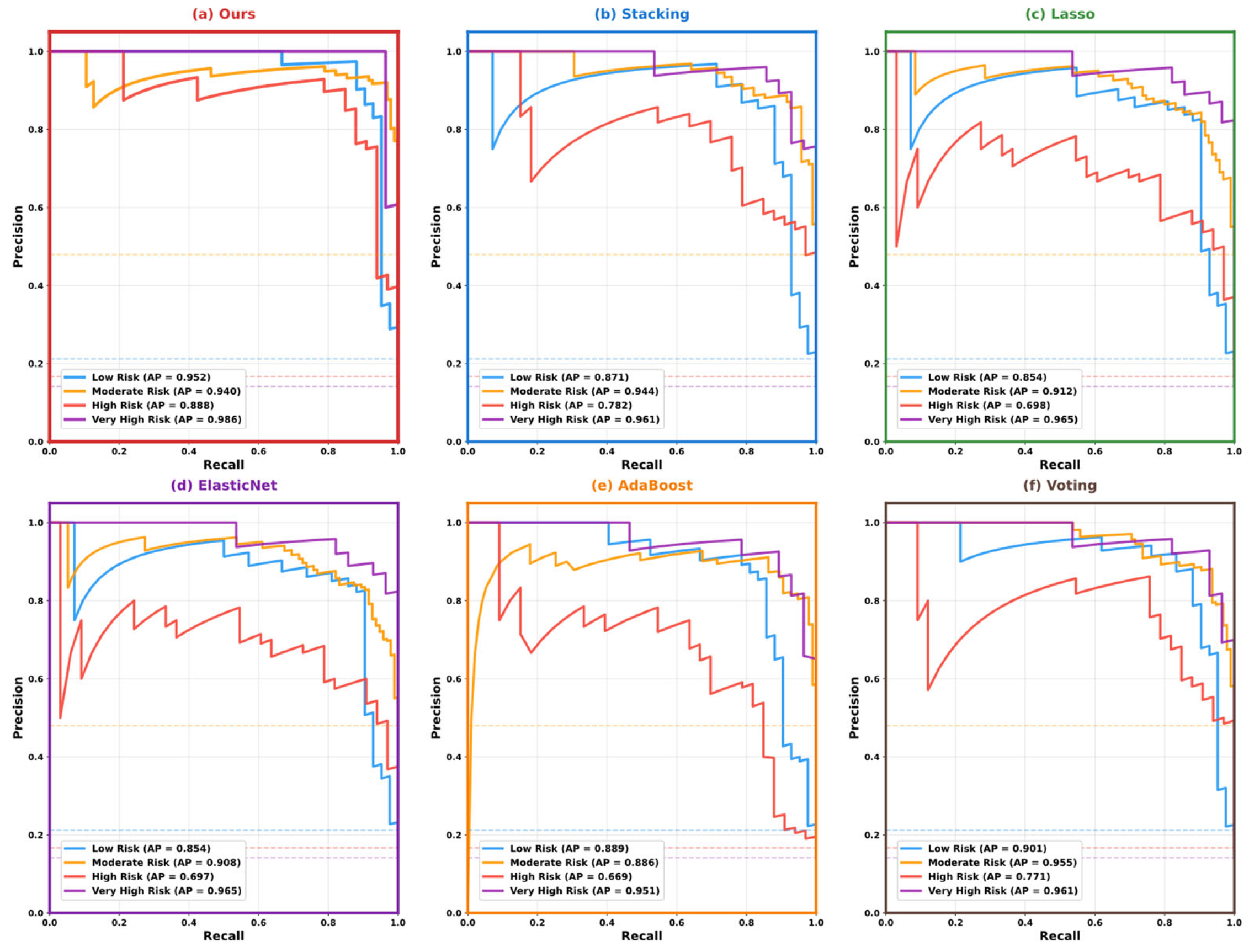

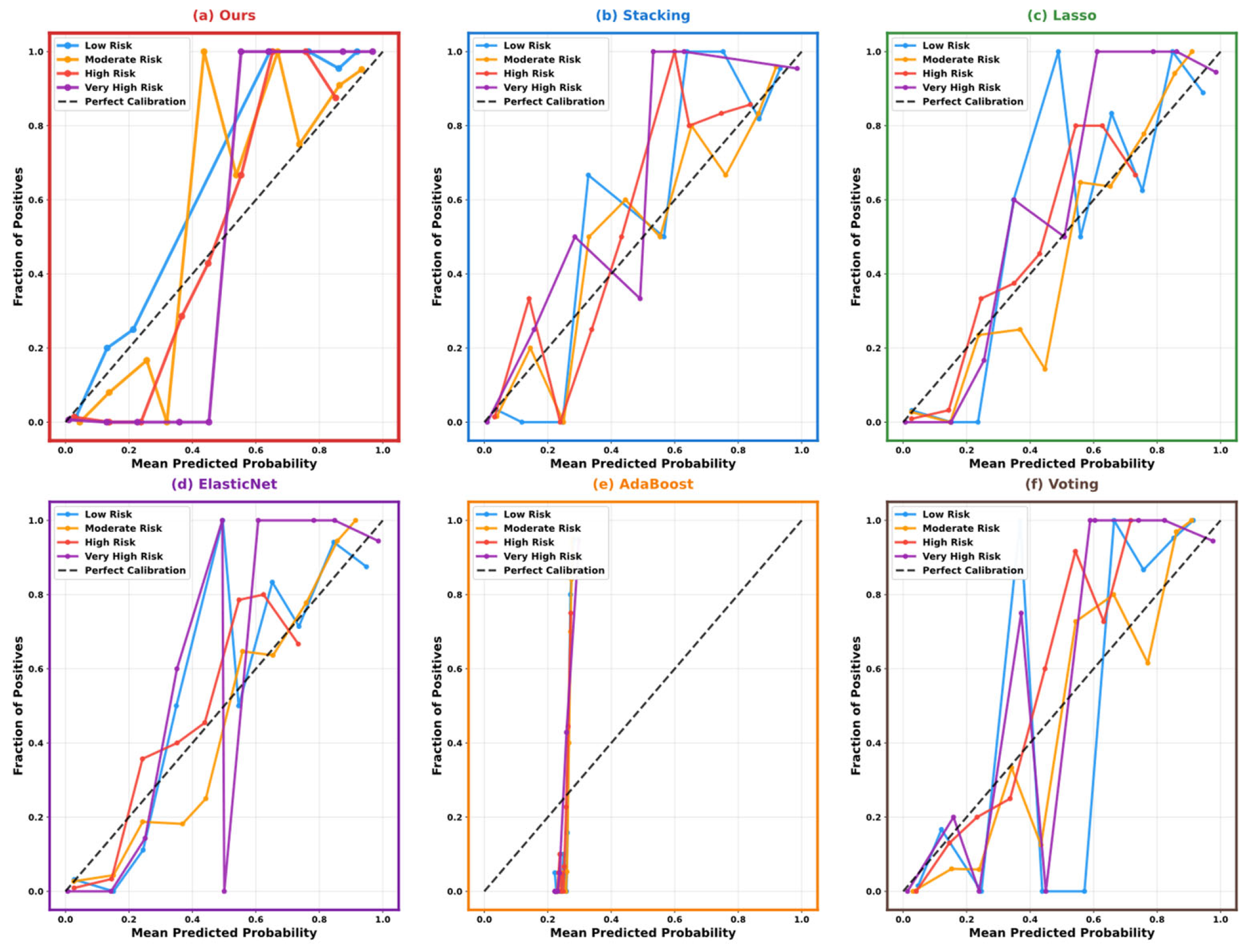

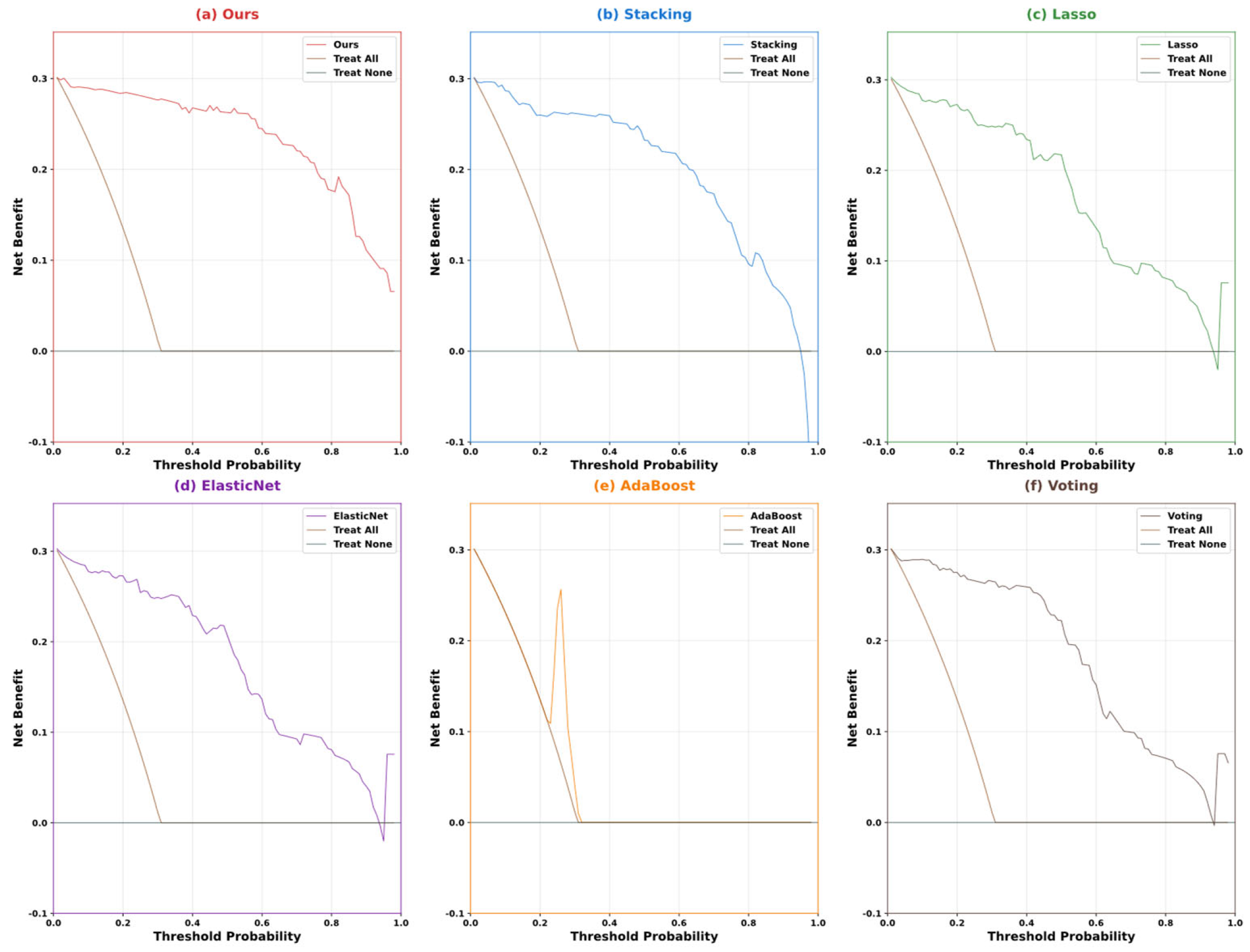

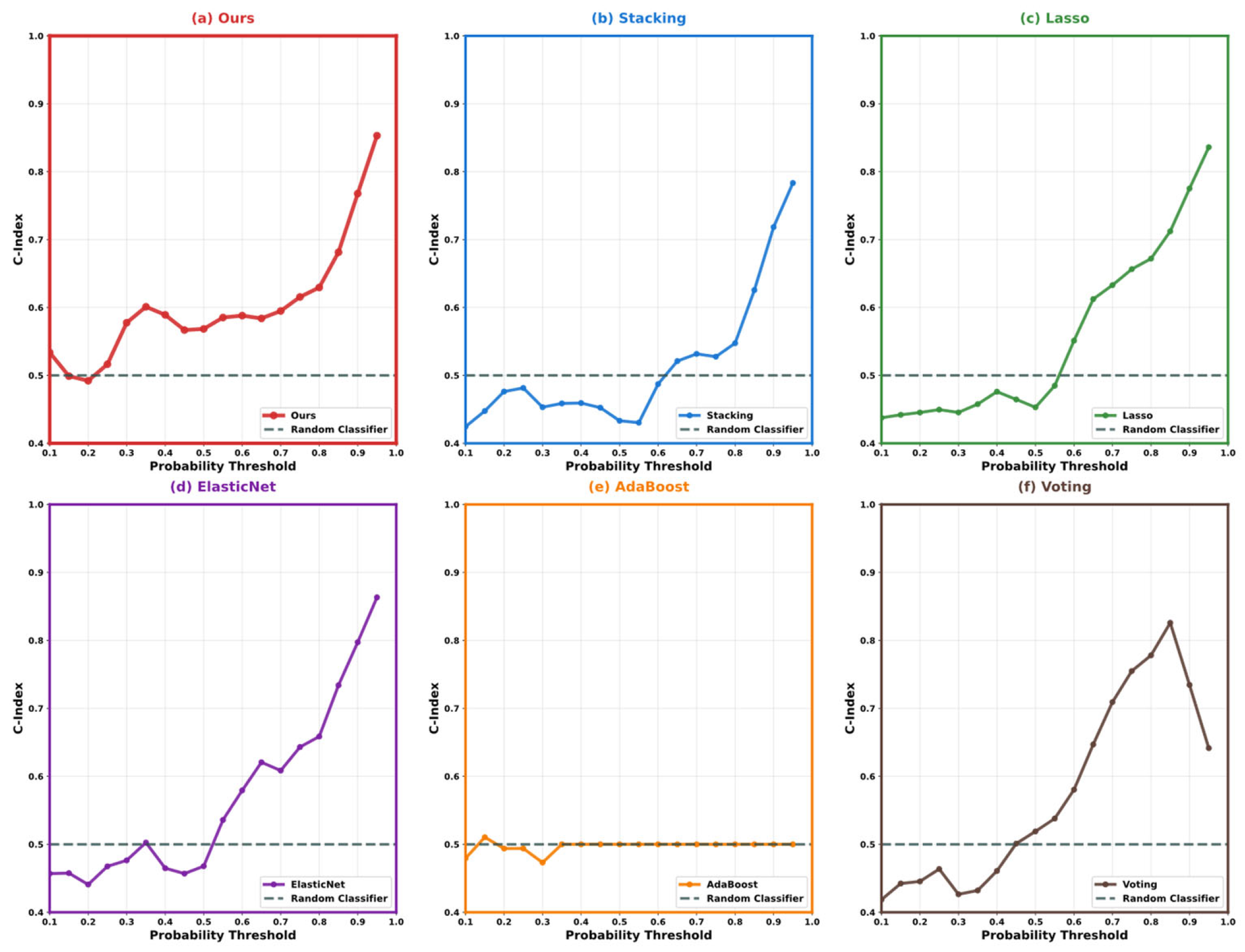

5.3. Model Performance Comparison and Analysis

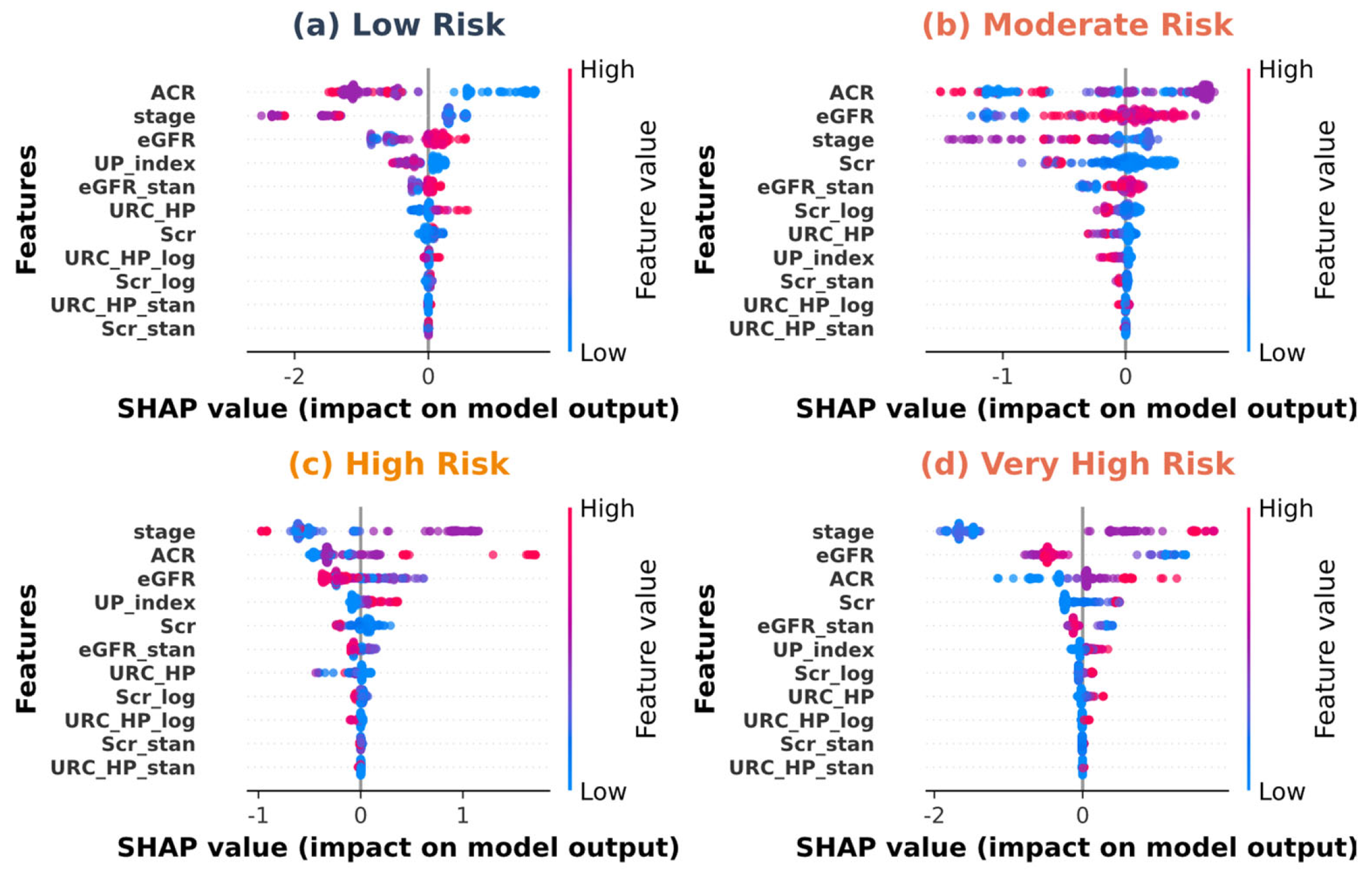

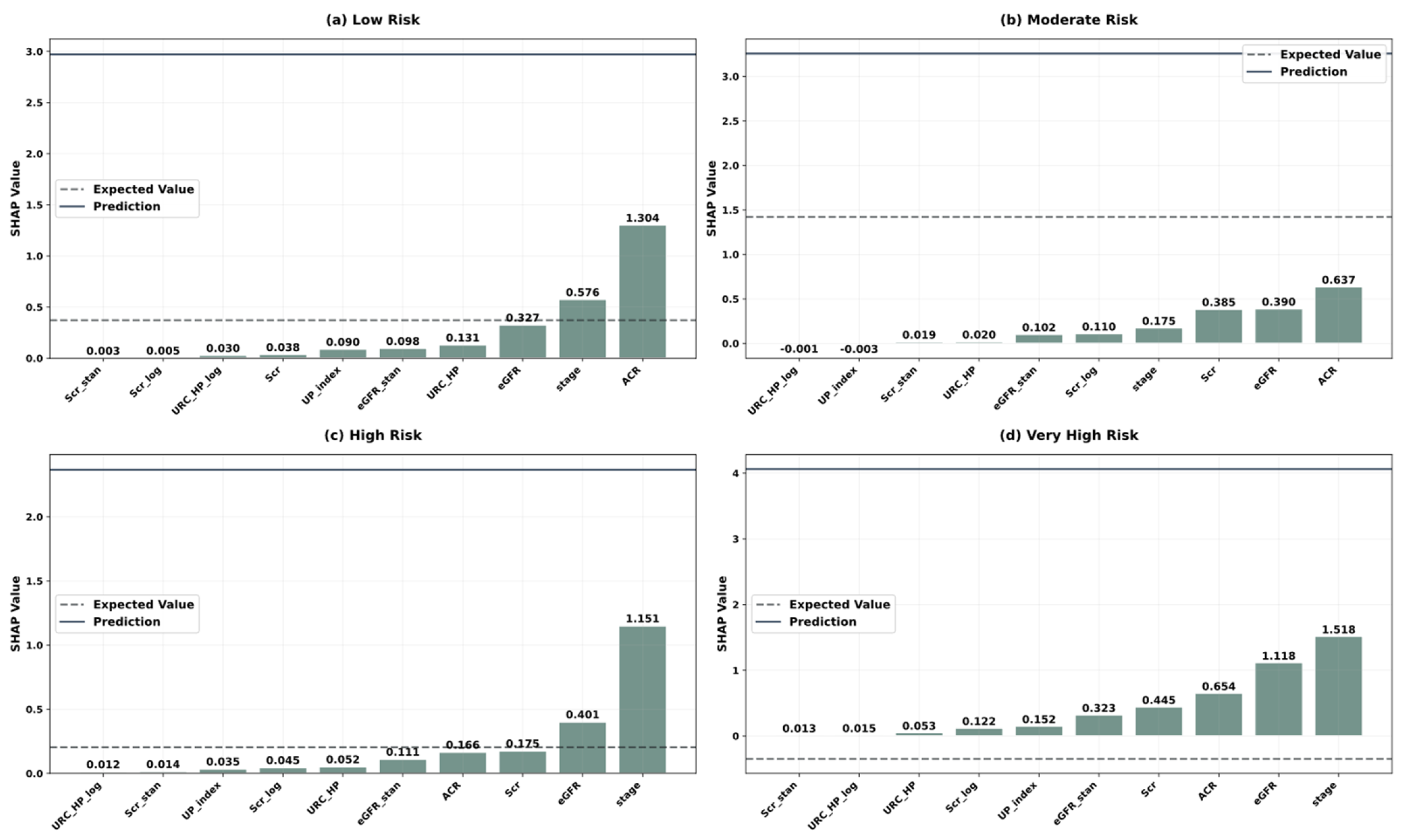

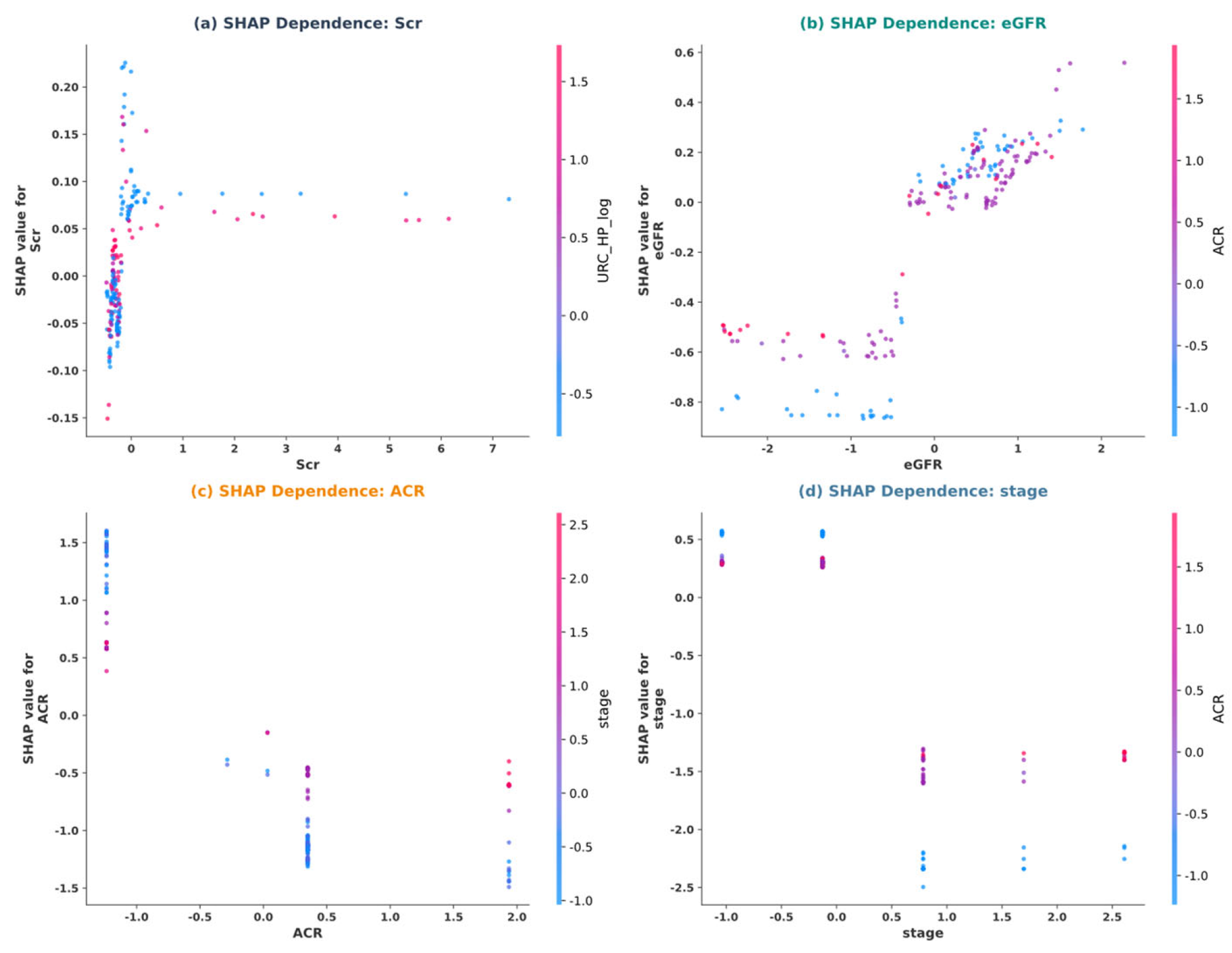

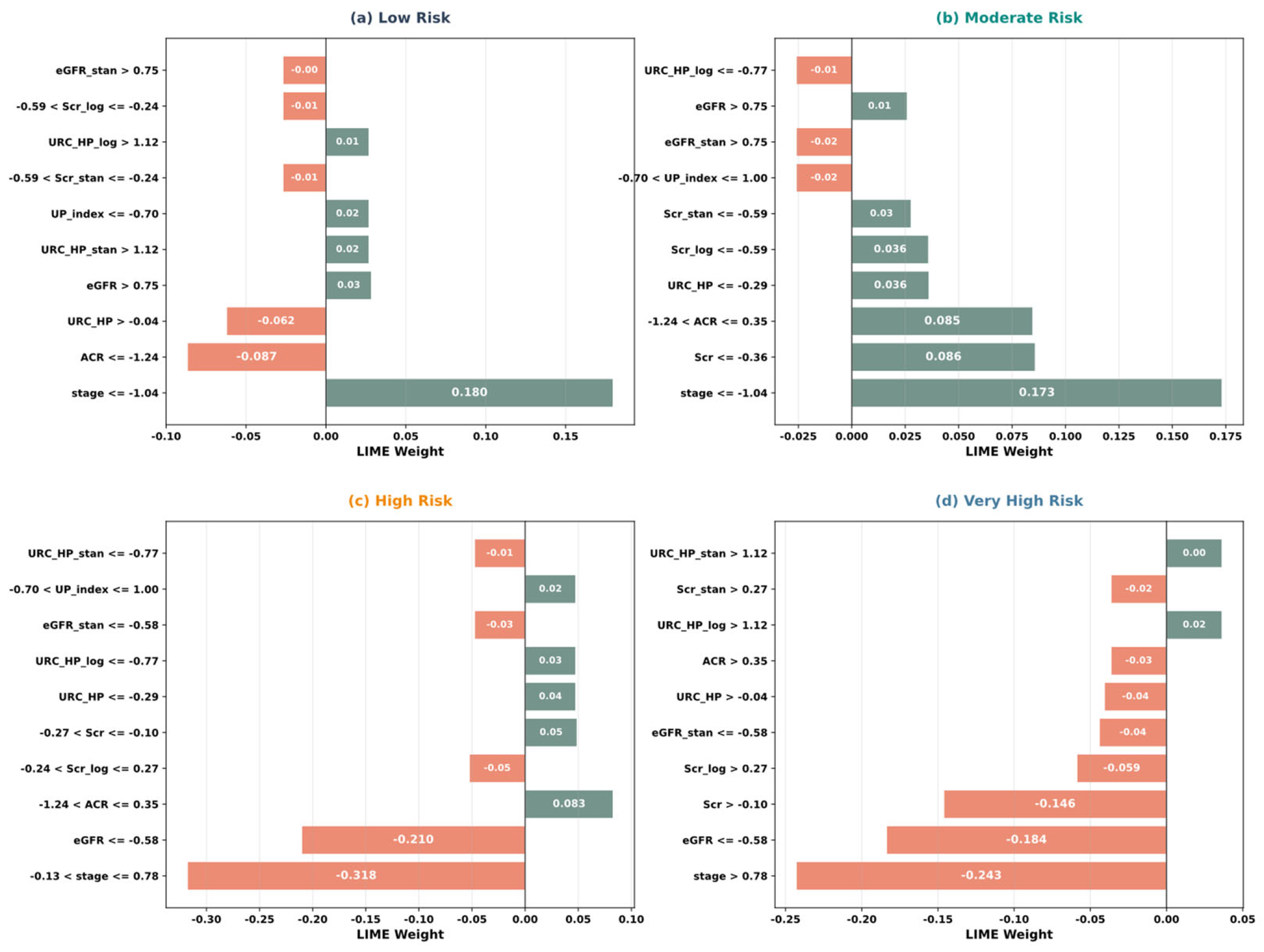

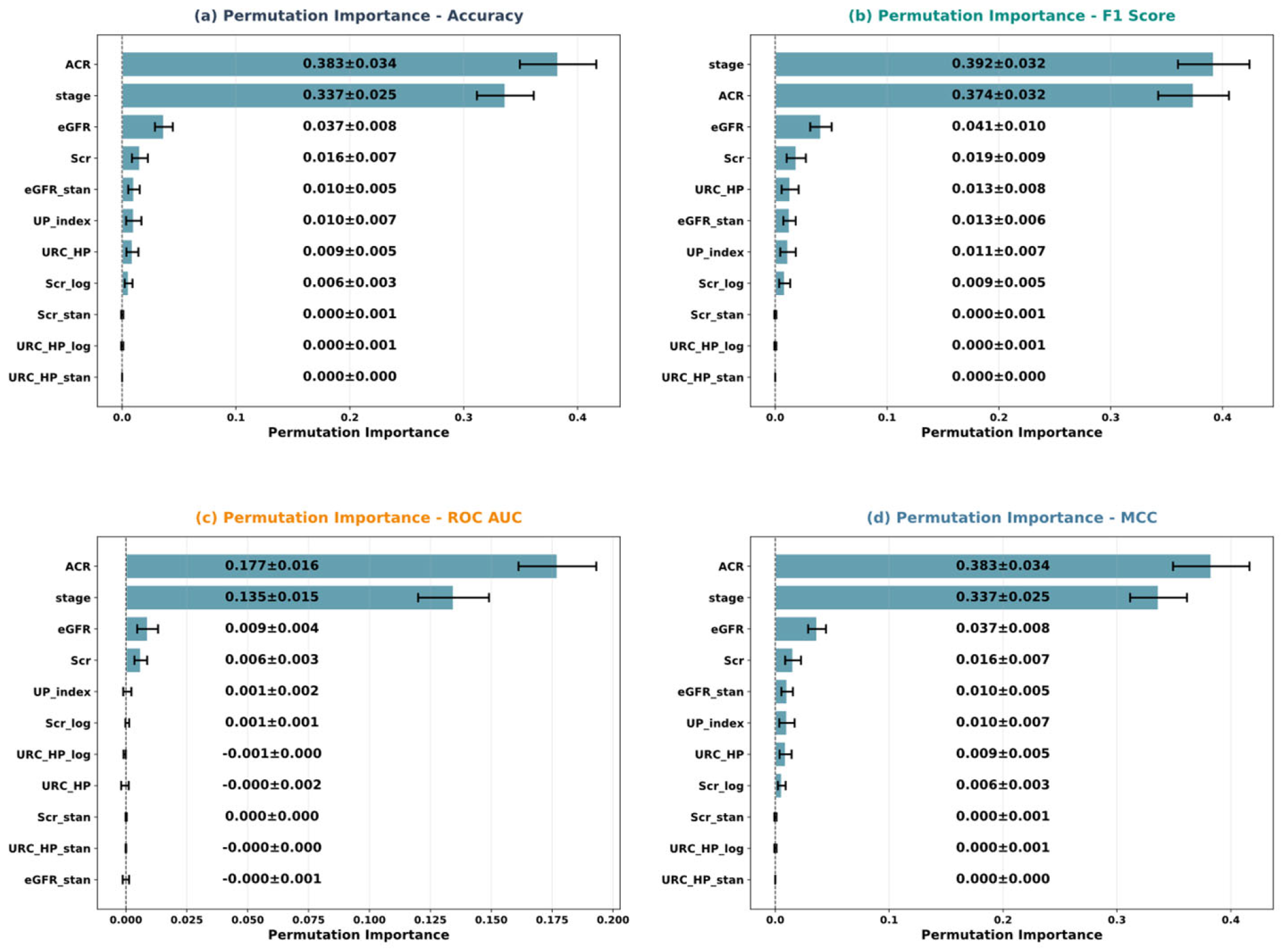

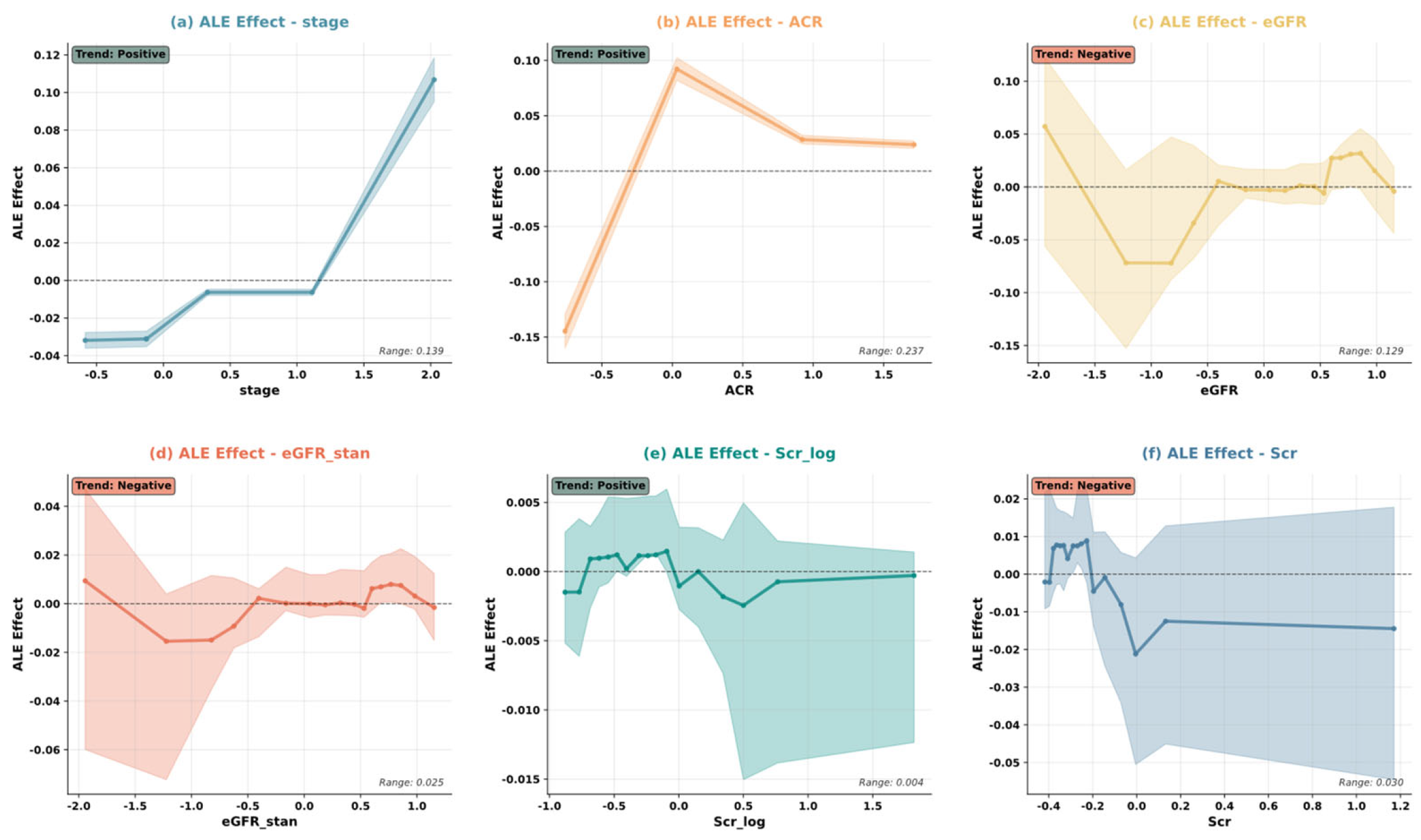

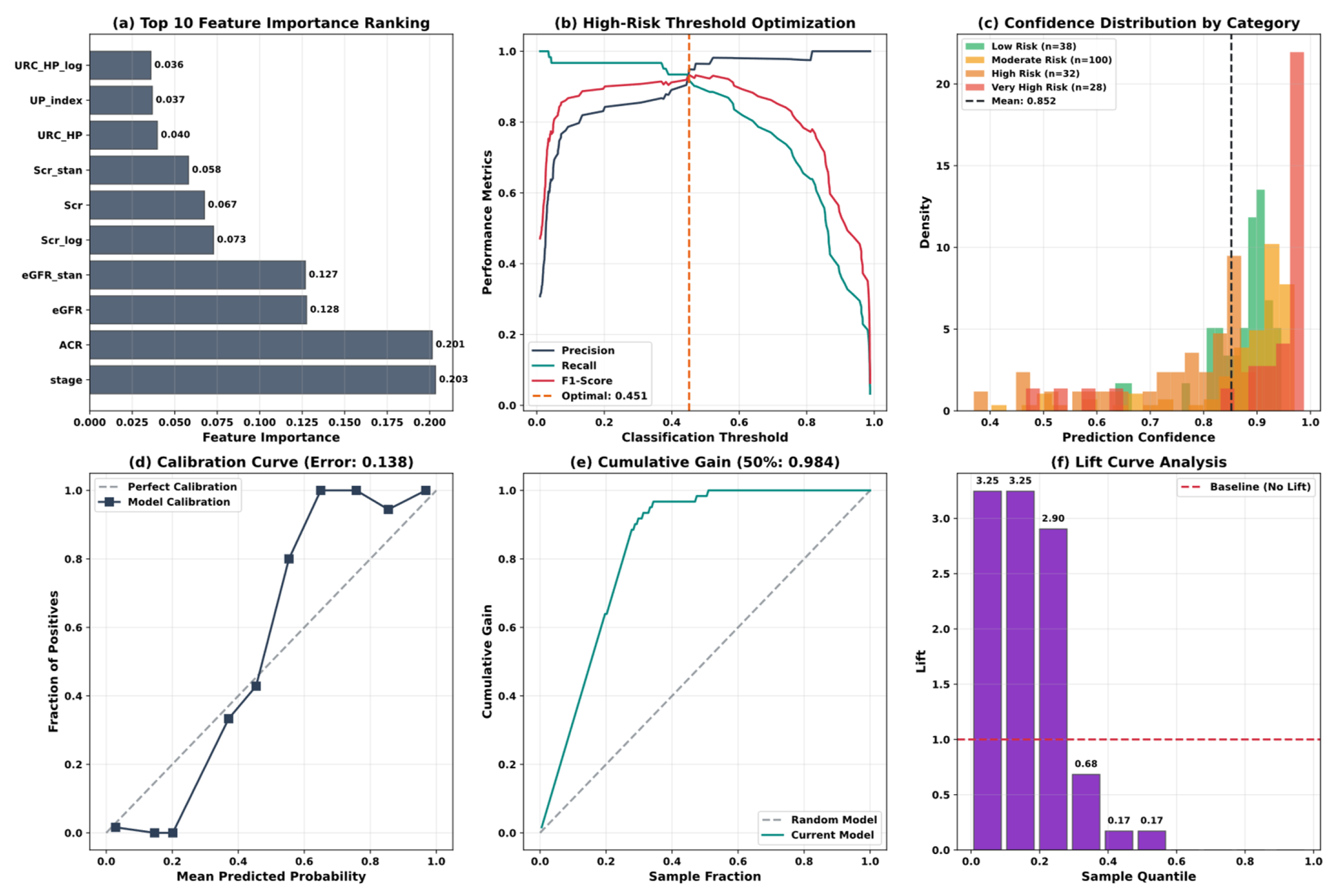

5.4. Model Interpretability Analysis

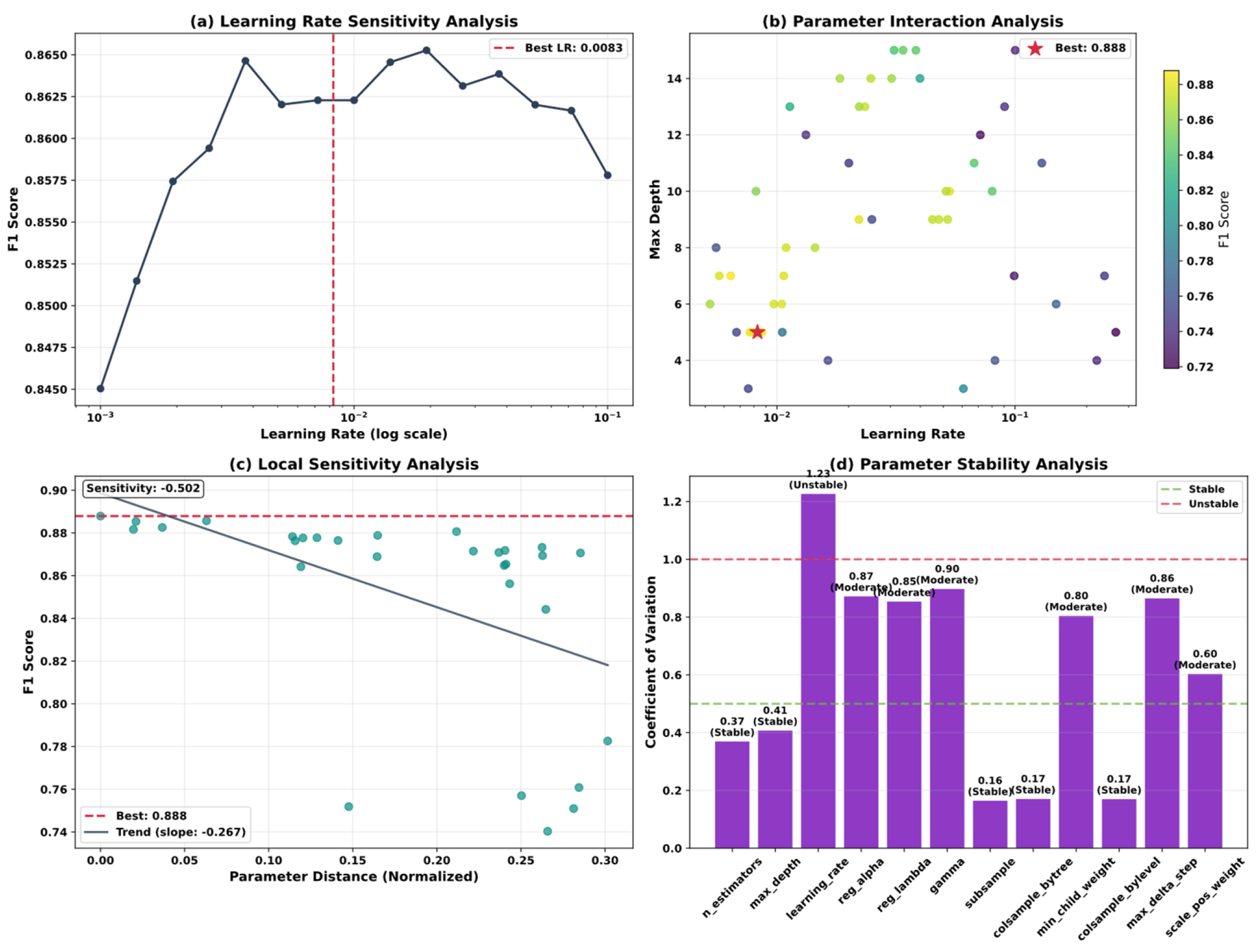

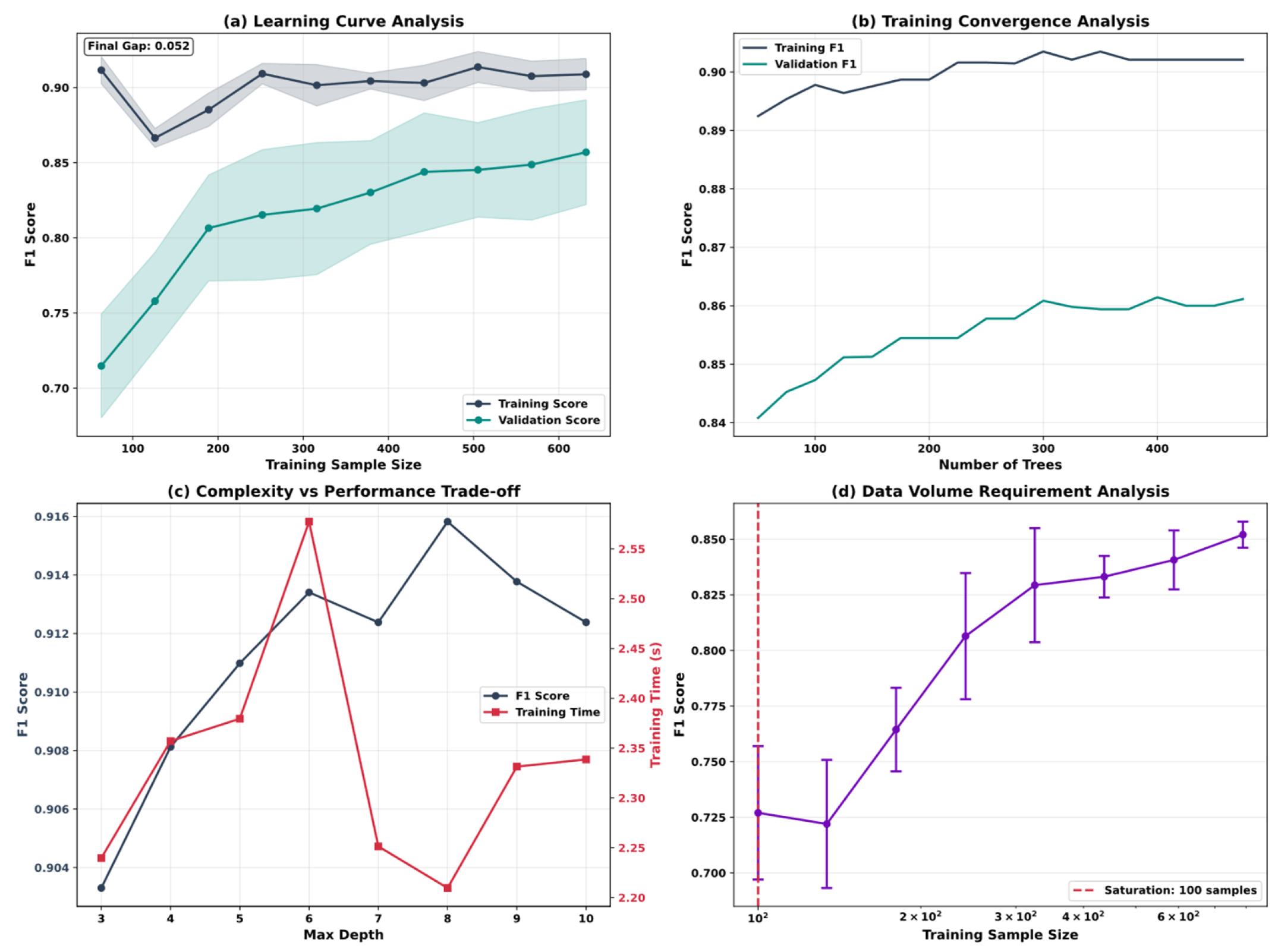

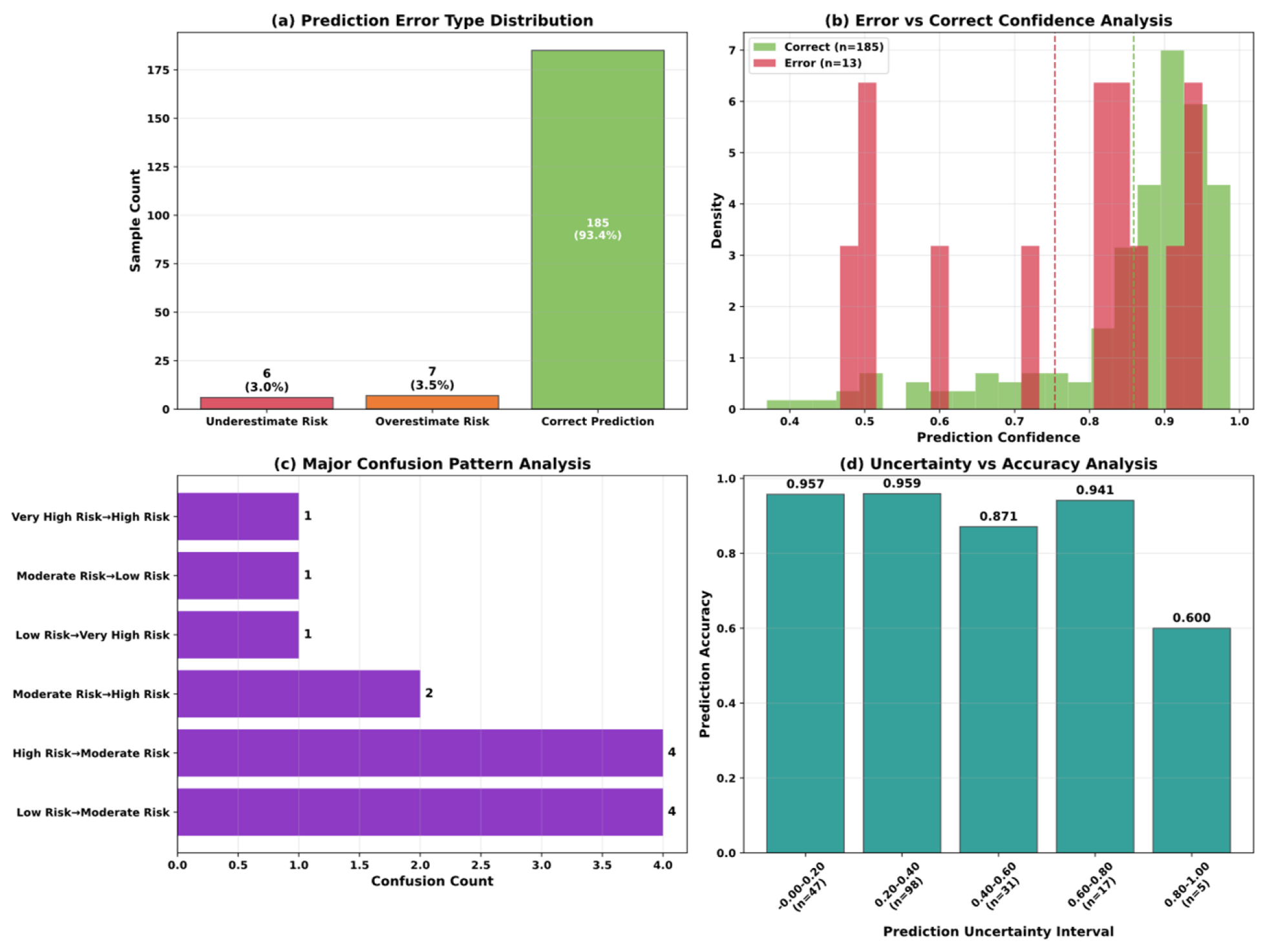

5.5. Model Optimization and Algorithm Performance Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, K.; Dubey, M.K.; Kajal; Dubey, S.; Pandey, D.K. Chronic Kidney Disease: Causes, Treatment, Management, and Future Scope. In Computational Intelligence for Genomics Data; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 99–111. ISBN 978-0-443-30080-6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Wan, Y.; Jiao, A.; Jiang, K.; Cui, G.; Tang, J.; Yu, S.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Yi, Z.; et al. Breaking Boundaries: Chronic Diseases and the Frontiers of Immune Microenvironments. Med Res. 2025, 1, 62–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yu, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Fang, S.; Pan, H.; Li, P.; Zhang, L. Guideline Concordance of Chronic Kidney Disease Testing Remains Low in Patients with Diabetes and Hypertension: Real-World Evidence from a City in Northwest China. Kidney Dis. 2025, 11, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaidi, S. Emerging Biomarkers and Advanced Diagnostics in Chronic Kidney Disease: Early Detection Through Multi-Omics and AI. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, U.; Chiwhane, A.; Acharya, S.; Daiya, V.; Kasat, P.R.; Sachani, P.; Mapari, S.A.; Bedi, G.N. A Comprehensive Review of Advanced Biomarkers for Chronic Kidney Disease in Older Adults: Current Insights and Future Directions. Cureus 2024, 16, e70413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmaraj, K.; Muthusamy, K.; Kannan, M.; Nanjan, M.; Ayyasamy, M.; Andrew, A.M. Diagnosing the Chronic Renal Disease Prediction by Using Random Forest and Bagged Tree. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Robotics, Automation and Intelligent Systems (ICRAINS 24), Coimbatore, India, 19 April 2025; p. 030010. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.; Sultana, A.; Islam, M.R. A Comprehensive Review for Chronic Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2024, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Khajuria, A.; Pachauri, R.K.; Gupta, V. Optimized Machine Learning Based Comparative Analysis of Predictive Models for Classification of Kidney Tumors. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, K.K.; Gopala Krishna, J.S.V.; Sravani, K.; Panda, B.S.; Panda, G.; Shankar, R.S. A Model for Predicting Chronic Renal Failure Using CatBoost Classifier Algorithm and XGBClassifier. In Proceedings of the 2024 Second International Conference on Inventive Computing and Informatics (ICICI), Bangalore, India, 11–12 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rahunathan, L.; Arun, G. Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction Using Light Gradient Boosting Machine. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Soft Computing for Security Applications (ICSCSA), Salem, India, 4–6 August 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1274–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Gogoi, P.; Valan, J.A. Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting and Diagnosing Chronic Kidney Disease: Current Trends, Challenges, Solutions, and Future Directions. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2024, 57, 1245–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, R.; Sultana, A.; Tuhin, M.N. A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms with Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator for Liver Disease Prediction. Healthc. Anal. 2024, 6, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Khandoker, A.H. Investigation on Explainable Machine Learning Models to Predict Chronic Kidney Diseases. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliappan, J.; Saravana Kumar, I.J.; Sundaravelan, S.; Anesh, T.; Rithik, R.R.; Singh, Y.; Vera-Garcia, D.V.; Himeur, Y.; Mansoor, W.; Atalla, S.; et al. Analyzing Classification and Feature Selection Strategies for Diabetes Prediction across Diverse Diabetes Datasets. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 1421751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Global Public Health Agenda: An International Consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Amin, A.; Hossain, J. Machine Learning Models for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Prediction. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 87, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ahmed, N.; Barczak, A.L.C. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for CKD Risk Prediction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 171205–171220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metherall, B.; Berryman, A.K.; Brennan, G.S. Machine Learning for Classifying Chronic Kidney Disease and Predicting Creatinine Levels Using At-Home Measurements. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Raza, M.A.; Mirjat, N.H.; Balouch, N.; Abbas, G.; Yousef, A.; Touti, E. Unveiling the Predictive Power: A Comprehensive Study of Machine Learning Model for Anticipating Chronic Kidney Disease. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 1339988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.; Roy, S.; Choy, K.W.; Sharma, S.; Dwyer, K.M.; Manapragada, C.; Miller, Z.; Cheon, J.; Nakisa, B. Predicting Chronic Kidney Disease Progression Using Small Pathology Datasets and Explainable Machine Learning Models. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2024, 6, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifuzzaman, M.; Fahad, N.; Rabbi, R.I.; Sadib, R.J.; Haque Tusher, E.; Liew, T.H.; Naimul Islam, M.; Ullah Miah, M.S.; Hossen, M.J. Optimized Machine Learning Models and Stacking Hybrid Approach for Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction. In Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations; Maglogiannis, I., Iliadis, L., Andreou, A., Papaleonidas, A., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 758, pp. 196–212. ISBN 978-3-031-96234-9. [Google Scholar]

- Siregar, M.R.; Hartama, D.; Solikhun, S. Optimizing the KNN Algorithm for Classifying Chronic Kidney Disease Using Gridsearchcv. JITK 2025, 10, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Sandhu, J.K.; Kumar, Y. Metaheuristic-Based Hyperparameter Optimization for Multi-Disease Detection and Diagnosis in Machine Learning. SOCA 2024, 18, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A.; Saxena, A.; Thakur, A.; Bhartiya, A.K. Enhanced Predictive Modeling for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Advanced Computing and Emerging Technologies (ACET), Ghaziabad, India, 23–24 August 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Luaha, L.; Fahmi, F.; Zarlis, M. Performance Analysis of Support Vector Machine (SVM) Model Through Parameter Optimization with Genetic Algorithm (GA) in Chronic Kidney Disease Classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electrical, Telecommunication and Computer Engineering (ELTICOM), Medan, Indonesia, 21–22 November 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Jyothirmaye, S.; Meyyappan, S.; Ilavarasan, S.; Muthupandi, M.; Vallathan, G.; Kasturi, K.S. Revolutionizing CKD Prediction with Bayesian- Optimized LightGBM for Clinical Decision Support. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Emerging Technologies in Engineering Applications (ICETEA), Puducherry, India, 5–6 June 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, M. BO–FTT: A Deep Learning Model Based on Parameter Tuning for Early Disease Prediction from a Case of Anemia in CKD. Electronics 2025, 14, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathne, G.; Bogahawaththa, M.; McAfee, M.; Rathnayake, U.; Meddage, D.P.P. On the Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease Using a Machine Learning-Based Interface with Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2024, 22, 200397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, N.G.; Alshathri, S.; Sayed, A.; Hemdan, E.E.-D. Explainable AI for Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction in Medical IoT: Integrating GANs and Few-Shot Learning. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manju, V.N.; Aparna, N.; Krishna Sowjanya, K. Decision Tree-Based Explainable AI for Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 3–5 August 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 947–952. [Google Scholar]

- Tawsik Jawad, K.M.; Verma, A.; Amsaad, F.; Ashraf, L. A Study on the Application of Explainable AI on Ensemble Models for Predictive Analysis of Chronic Kidney Disease. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 23312–23330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Sun, W.; Hu, K.; He, W.; Xie, J. Identification and Validation of an Explainable Early-Stage Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction Model: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 84, 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, J.; Song, L.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Xu, S.; Shi, K.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; et al. Explainable Machine Learning Model for Predicting Persistent Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Development and Validation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e62932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Shen, C.; Xue, H.; Yuan, B.; Zheng, B.; Shen, L.; Fang, X. Development of an Early Prediction Model for Vomiting during Hemodialysis Using LASSO Regression and Boruta Feature Selection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Dai, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, B.; Liang, L.; Liang, C.; Lu, C.; Tan, Q.; Wei, C.; Tan, Y.; et al. Identification of Optimal Biomarkers Associated with Distant Metastasis in Breast Cancer Using Boruta and Lasso Machine Learning Algorithms. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Shi, F.; Ding, W.; Fang, C.; Fang, C. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Model for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Sun, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, L. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: Model Development and Clinical Validation. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1614657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, B.B.; Gal, D. Statistical Significance and the Dichotomization of Evidence. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2017, 112, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagner, A.; Biganzoli, E.M.; Balsano, C.; Cereda, C.; Cabitza, F. Modeling Unknowns: A Vision for Uncertainty-Aware Machine Learning in Healthcare. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 203, 106014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goligher, E.C.; Heath, A.; Harhay, M.O. Bayesian Statistics for Clinical Research. Lancet 2024, 404, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Dang, T.; Han, J.; Qendro, L.; Mascolo, C. Uncertainty-Aware Health Diagnostics via Class-Balanced Evidential Deep Learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 6417–6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, E.; Das, A.; Hsueh, P.-Y.S.; Solomonides, A.; Joseph, A.L.; Srivastava, G.; Johnson, C.E.; Kannry, J.; Oladimeji, B.; Price, A.; et al. Towards Responsible Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare—Getting Real about Real-World Data and Evidence. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 1746–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Li, L.; Chen, J. Multi-Armed Bandit Optimization for Explainable AI Models in Chronic Kidney Disease Risk Evaluation. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, L.; Hou, M.; Chen, J. Bayesian Optimization Meets Explainable AI: Enhanced Chronic Kidney Disease Risk Assessment. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornec-Le Gall, E.; Torres, V.E.; Harris, P.C. Genetic Complexity of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Diseases. JASN 2018, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Adamczak, M.; De Oliveira, R.B.; Massy, Z.A.; Sarafidis, P.; Agarwal, R.; Mark, P.B.; Kotanko, P.; Ferro, C.J.; et al. Cardiovascular Complications in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review from the European Renal and Cardiovascular Medicine Working Group of the European Renal Association. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2017–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallan, S.I.; Ritz, E.; Lydersen, S.; Romundstad, S.; Kvenild, K.; Orth, S.R. Combining GFR and Albuminuria to Classify CKD Improves Prediction of ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; De Jong, P.E.; Coresh, J.; El Nahas, M.; Astor, B.C.; Matsushita, K.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Kasiske, B.L.; Eckardt, K.-U. The Definition, Classification, and Prognosis of Chronic Kidney Disease: A KDIGO Controversies Conference Report. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable Name | Description | Values/Range |

|---|---|---|

| hos_id | Hospital ID | 7 hospitals |

| hos_name | Hospital Name | Hospital names |

| gender | Gender | Male/Female |

| genetic | Hereditary Kidney Disease | Y/N |

| family | Family History of Chronic Nephritis | Y/N |

| transplant | Kidney Transplant History | Y/N |

| biopsy | Renal Biopsy History | Y/N |

| HBP | Hypertension History | Y/N |

| diabetes | Diabetes Mellitus History | Y/N |

| hyperuricemia | Hyperuricemia | Y/N |

| UAS | Urinary Anatomical Structure Abnormality | −/Y/N |

| ACR | Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio | <30/30–300/>300 mg/g |

| UP_positive | Urine Protein Test | Negative/Positive |

| UP_index | Urine Protein Index | ± (0.1–0.2 g/L) + (0.2–1.0) 2+ (1.0–2.0) 3+ (2.0–4.0) 5+ (>4.0) |

| URC_unit | Urine RBC Unit | HP-per high power field μL-per microliter |

| URC_num | Urine RBC Count | 0–93.9 Different units |

| Scr | Serum Creatinine | 0/27.2–85,800 μmol/L |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate | 2.5–148 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| date | Diagnosis Date | 13 December 2016–27 January 2018 |

| rate | CKD Risk Stratification | Low/Moderate/High/Very High Risk |

| stage | CKD Stage | CKD Stage 1/2/3/4/5 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | MCC | Cohen Kappa | ROC AUC | CV_Mean | CV_Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 0.9343 | 0.9411 | 0.9231 | 0.9313 | 0.9028 | 0.9020 | 0.9759 | 0.8835 | 0.0181 |

| XGBoost | 0.8788 | 0.8754 | 0.8634 | 0.8691 | 0.82 | 0.8198 | 0.9568 | 0.8456 | 0.013 |

| LightGBM | 0.8737 | 0.8661 | 0.8578 | 0.8614 | 0.8132 | 0.8131 | 0.9582 | 0.8405 | 0.0141 |

| CatBoost | 0.8687 | 0.8629 | 0.8307 | 0.8452 | 0.8039 | 0.8024 | 0.963 | 0.8544 | 0.0165 |

| Voting | 0.8636 | 0.8723 | 0.8297 | 0.8487 | 0.7962 | 0.7942 | 0.9634 | 0.8291 | 0.0144 |

| RandomForest | 0.8636 | 0.8644 | 0.836 | 0.8491 | 0.7965 | 0.7954 | 0.9639 | 0.8278 | 0.0189 |

| Bagging | 0.8586 | 0.8614 | 0.8284 | 0.8433 | 0.7887 | 0.7872 | 0.9651 | 0.8304 | 0.0152 |

| Stacking | 0.8586 | 0.8586 | 0.8235 | 0.8385 | 0.7888 | 0.7867 | 0.9596 | 0.8304 | 0.0298 |

| GBDT | 0.8535 | 0.8538 | 0.8258 | 0.8388 | 0.7813 | 0.7802 | 0.9579 | 0.8165 | 0.0139 |

| KNeighbors | 0.8535 | 0.8558 | 0.81 | 0.8293 | 0.7809 | 0.7783 | 0.9209 | 0.8228 | 0.004 |

| ExtraTrees | 0.8535 | 0.864 | 0.8044 | 0.8271 | 0.7818 | 0.776 | 0.9628 | 0.8063 | 0.0203 |

| AdaBoost | 0.8434 | 0.8491 | 0.7958 | 0.8168 | 0.766 | 0.7611 | 0.9347 | 0.8139 | 0.0221 |

| SVM | 0.8384 | 0.8372 | 0.7839 | 0.8055 | 0.758 | 0.7533 | 0.9526 | 0.8278 | 0.0162 |

| Logistic | 0.8333 | 0.8394 | 0.7955 | 0.8133 | 0.7504 | 0.7473 | 0.9498 | 0.8063 | 0.013 |

| ElasticNet | 0.8333 | 0.8394 | 0.7955 | 0.8133 | 0.7504 | 0.7473 | 0.9501 | 0.8051 | 0.0167 |

| Lasso | 0.8283 | 0.8316 | 0.7929 | 0.8091 | 0.7428 | 0.7403 | 0.9499 | 0.8063 | 0.0153 |

| DecisionTree | 0.8131 | 0.8079 | 0.7453 | 0.7694 | 0.7189 | 0.7137 | 0.8999 | 0.7443 | 0.0242 |

| MLP | 0.7929 | 0.7951 | 0.7247 | 0.7335 | 0.6926 | 0.6775 | 0.9355 | 0.7291 | 0.0493 |

| GaussianNB | 0.7475 | 0.7705 | 0.7191 | 0.731 | 0.6333 | 0.6283 | 0.908 | 0.6987 | 0.0403 |

| Ridge | 0.7273 | 0.6976 | 0.6403 | 0.6221 | 0.5913 | 0.5693 | 0.8999 | 0.7013 | 0.0221 |

| Perceptron | 0.6515 | 0.6667 | 0.7153 | 0.6664 | 0.5493 | 0.527 | 0.8999 | 0.6709 | 0.0243 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | MCC | Cohen Kappa | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 0.860 ± 0.023 | 0.859 ± 0.027 | 0.844 ± 0.025 | 0.850 ± 0.025 | 0.793 ± 0.034 | 0.792 ± 0.034 | 0.946 ± 0.014 |

| Stacking | 0.850 ± 0.027 | 0.846 ± 0.029 | 0.821 ± 0.032 | 0.831 ± 0.030 | 0.776 ± 0.041 | 0.775 ± 0.041 | 0.948 ± 0.014 |

| Lasso | 0.844 ± 0.022 | 0.854 ± 0.026 | 0.813 ± 0.025 | 0.828 ± 0.024 | 0.768 ± 0.034 | 0.764 ± 0.034 | 0.943 ± 0.012 |

| ElasticNet | 0.840 ± 0.020 | 0.850 ± 0.026 | 0.809 ± 0.021 | 0.824 ± 0.022 | 0.762 ± 0.030 | 0.758 ± 0.030 | 0.941 ± 0.012 |

| Logistic | 0.834 ± 0.020 | 0.838 ± 0.026 | 0.802 ± 0.022 | 0.816 ± 0.023 | 0.753 ± 0.030 | 0.750 ± 0.030 | 0.937 ± 0.013 |

| Voting | 0.835 ± 0.026 | 0.839 ± 0.032 | 0.798 ± 0.030 | 0.815 ± 0.030 | 0.754 ± 0.038 | 0.750 ± 0.038 | 0.947 ± 0.012 |

| AdaBoost | 0.829 ± 0.031 | 0.831 ± 0.035 | 0.798 ± 0.036 | 0.811 ± 0.035 | 0.746 ± 0.046 | 0.744 ± 0.046 | 0.937 ± 0.013 |

| XGBoost | 0.823 ± 0.027 | 0.815 ± 0.040 | 0.782 ± 0.034 | 0.794 ± 0.036 | 0.736 ± 0.041 | 0.734 ± 0.041 | 0.945 ± 0.013 |

| LightGBM | 0.827 ± 0.027 | 0.838 ± 0.042 | 0.772 ± 0.036 | 0.793 ± 0.038 | 0.742 ± 0.042 | 0.734 ± 0.042 | 0.948 ± 0.013 |

| Bagging | 0.816 ± 0.023 | 0.825 ± 0.036 | 0.756 ± 0.031 | 0.774 ± 0.033 | 0.726 ± 0.036 | 0.717 ± 0.037 | 0.945 ± 0.014 |

| SVM | 0.788 ± 0.022 | 0.789 ± 0.031 | 0.723 ± 0.031 | 0.746 ± 0.029 | 0.681 ± 0.035 | 0.673 ± 0.034 | 0.941 ± 0.015 |

| CatBoost | 0.801 ± 0.018 | 0.814 ± 0.038 | 0.728 ± 0.023 | 0.741 ± 0.027 | 0.705 ± 0.029 | 0.688 ± 0.029 | 0.932 ± 0.013 |

| GBDT | 0.778 ± 0.025 | 0.795 ± 0.041 | 0.702 ± 0.030 | 0.726 ± 0.031 | 0.668 ± 0.040 | 0.651 ± 0.040 | 0.940 ± 0.014 |

| RandomForest | 0.758 ± 0.033 | 0.784 ± 0.042 | 0.687 ± 0.037 | 0.716 ± 0.038 | 0.637 ± 0.053 | 0.620 ± 0.053 | 0.929 ± 0.014 |

| KNeighbors | 0.723 ± 0.032 | 0.735 ± 0.037 | 0.660 ± 0.038 | 0.686 ± 0.036 | 0.579 ± 0.050 | 0.571 ± 0.050 | 0.877 ± 0.019 |

| Perceptron | 0.705 ± 0.048 | 0.694 ± 0.050 | 0.686 ± 0.045 | 0.681 ± 0.043 | 0.569 ± 0.063 | 0.563 ± 0.063 | 0.000 ± 0.000 |

| DecisionTree | 0.694 ± 0.037 | 0.710 ± 0.046 | 0.642 ± 0.042 | 0.661 ± 0.042 | 0.540 ± 0.056 | 0.532 ± 0.056 | 0.854 ± 0.023 |

| MLP | 0.707 ± 0.047 | 0.684 ± 0.070 | 0.642 ± 0.055 | 0.645 ± 0.064 | 0.557 ± 0.074 | 0.546 ± 0.076 | 0.877 ± 0.034 |

| ExtraTrees | 0.715 ± 0.019 | 0.814 ± 0.064 | 0.608 ± 0.025 | 0.624 ± 0.029 | 0.581 ± 0.033 | 0.528 ± 0.034 | 0.923 ± 0.014 |

| Ridge | 0.713 ± 0.023 | 0.705 ± 0.081 | 0.632 ± 0.022 | 0.613 ± 0.023 | 0.569 ± 0.038 | 0.548 ± 0.036 | 0.000 ± 0.000 |

| GaussianNB | 0.431 ± 0.119 | 0.489 ± 0.113 | 0.542 ± 0.065 | 0.450 ± 0.097 | 0.352 ± 0.094 | 0.276 ± 0.119 | 0.857 ± 0.022 |

| Model | CV_F1 | CV_Mean | CV_Std | CV_Range | p-Value | 95% CI | Effect Size | 95% Credible Interval | Generalization Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 0.849 ± 0.012 | 0.8491 | 0.0121 | [0.8231, 0.8713] | — | — | — | — | −0.0113 |

| Stacking | 0.816 ± 0.011 | 0.8163 | 0.0108 | [0.7953, 0.8379] | <0.001 | [0.010, 0.027] | 0.665 | [0.011, 0.026] | −0.0333 |

| Lasso | 0.823 ± 0.008 | 0.8232 | 0.0085 | [0.8074, 0.8401] | <0.001 | [0.013, 0.031] | 0.873 | [0.013, 0.031] | −0.0210 |

| ElasticNet | 0.819 ± 0.010 | 0.8188 | 0.0095 | [0.8036, 0.8424] | <0.001 | [0.015, 0.036] | 1.067 | [0.015, 0.035] | −0.0214 |

| Logistic | 0.810 ± 0.008 | 0.8095 | 0.0085 | [0.7936, 0.8286] | <0.001 | [0.024, 0.044] | 1.412 | [0.024, 0.044] | −0.0247 |

| Voting | 0.800 ± 0.011 | 0.8002 | 0.0107 | [0.7734, 0.8274] | <0.001 | [0.027, 0.044] | 1.278 | [0.027, 0.043] | −0.0348 |

| AdaBoost | 0.807 ± 0.013 | 0.8068 | 0.0134 | [0.7679, 0.8287] | <0.001 | [0.029, 0.048] | 1.267 | [0.029, 0.048] | −0.0227 |

| XGBoost | 0.760 ± 0.015 | 0.7596 | 0.0147 | [0.7276, 0.7900] | <0.001 | [0.045, 0.066] | 1.795 | [0.045, 0.065] | −0.0638 |

| LightGBM | 0.783 ± 0.017 | 0.7832 | 0.0172 | [0.7517, 0.8190] | <0.001 | [0.046, 0.068] | 1.749 | [0.046, 0.067] | −0.0436 |

| Bagging | 0.765 ± 0.020 | 0.7646 | 0.0195 | [0.7225, 0.7948] | <0.001 | [0.065, 0.086] | 2.566 | [0.065, 0.085] | −0.0517 |

| SVM | 0.705 ± 0.020 | 0.7053 | 0.0197 | [0.6678, 0.7427] | <0.001 | [0.093, 0.115] | 3.799 | [0.093, 0.114] | −0.0828 |

| CatBoost | 0.731 ± 0.016 | 0.7310 | 0.0160 | [0.7039, 0.7642] | <0.001 | [0.099, 0.119] | 4.139 | [0.099, 0.118] | −0.0695 |

| GBDT | 0.677 ± 0.013 | 0.6767 | 0.0128 | [0.6538, 0.7051] | <0.001 | [0.114, 0.134] | 4.4 | [0.114, 0.133] | −0.1013 |

| RandomForest | 0.715 ± 0.021 | 0.7148 | 0.0208 | [0.6718, 0.7482] | <0.001 | [0.121, 0.146] | 4.166 | [0.121, 0.145] | −0.0436 |

| KNeighbors | 0.679 ± 0.014 | 0.6787 | 0.0135 | [0.6548, 0.7062] | <0.001 | [0.150, 0.177] | 5.259 | [0.150, 0.175] | −0.0442 |

| Perceptron | 0.674 ± 0.019 | 0.6742 | 0.0189 | [0.6366, 0.7221] | <0.001 | [0.151, 0.187] | 4.795 | [0.150, 0.185] | −0.0304 |

| DecisionTree | 0.650 ± 0.023 | 0.6500 | 0.0234 | [0.6152, 0.7166] | <0.001 | [0.171, 0.207] | 5.433 | [0.170, 0.205] | −0.0438 |

| MLP | 0.609 ± 0.049 | 0.6094 | 0.0487 | [0.4918, 0.6686] | <0.001 | [0.178, 0.232] | 4.243 | [0.177, 0.227] | −0.0976 |

| ExtraTrees | 0.615 ± 0.017 | 0.6150 | 0.0170 | [0.5859, 0.6442] | <0.001 | [0.214, 0.238] | 8.361 | [0.214, 0.237] | −0.0997 |

| Ridge | 0.619 ± 0.011 | 0.6185 | 0.0113 | [0.5970, 0.6388] | <0.001 | [0.226, 0.247] | 9.707 | [0.225, 0.246] | −0.0943 |

| GaussianNB | 0.444 ± 0.051 | 0.4437 | 0.0509 | [0.3621, 0.5626] | <0.001 | [0.364, 0.435] | 5.653 | [0.354, 0.420] | 0.0131 |

| Model | N_Estimators | Max_Depth | Learning_Rate | Subsample | Colsample_Bytree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | (200, 2000) | (3, 15) | log(0.005–0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| ASHA | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| Auto-sklearn | [50, 2000] | [3, 15] | [0.01, 0.3] | [0.5, 1.0] | [0.5, 1.0] |

| BOHB | (200, 2000) | (3, 15) | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| CMA-ES | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| Differential Evolution | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| FLAML | [50, 2000] | [3, 15] | [0.01, 0.3] | [0.6, 1.0] | [0.6, 1.0] |

| Genetic Algorithm | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| Grid Search | [100, 800] | [3, 8] | [0.01, 0.2] | [0.7, 1.0] | [0.7, 1.0] |

| H2O AutoML | [50, 2000] | [4, 15] | [0.03, 0.3] | [0.7, 1.0] | [0.7, 1.0] |

| Hyperband | [100, 2000] | [3, 15] | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| Hyperopt | [100, 2000] | [3, 15] | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| MAB | [200, 2000] | [3, 15] | [0.05–0.3] | [0.8, 1.0] | [0.8, 1.0] |

| PSO | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| PBT | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | log(0.01–0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| Random Search | [200, 2000] | [3, 15] | [0.005, 0.3] | [0.5, 1.0] | [0.5, 1.0] |

| Scikit-Optimize | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | (0.01, 0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| Successive Halving | (100, 2000) | (3, 15) | log(0.01–0.3) | (0.5, 1.0) | (0.5, 1.0) |

| Thompson Sampling | [200, 2000] | [3, 15] | [0.05, 0.3] | [0.8, 1.0] | [0.8, 1.0] |

| UCB | [100, 2000] | [3, 15] | [0.01, 0.3] | [0.5, 1.0] | [0.5, 1.0] |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | MCC | Cohen Kappa | ROC AUC | CV Mean | CV Std | Generalization Gap | Evaluations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 0.9343 | 0.9411 | 0.9231 | 0.9313 | 0.9028 | 0.9020 | 0.9759 | 0.8835 | 0.0182 | −0.0508 | 50 |

| Random Search | 0.9293 | 0.9320 | 0.9155 | 0.9227 | 0.8953 | 0.8945 | 0.9769 | 0.8684 | 0.0129 | −0.0609 | 50 |

| PBT | 0.9242 | 0.9247 | 0.9129 | 0.9180 | 0.8878 | 0.8872 | 0.9707 | 0.8633 | 0.0065 | −0.0610 | 50 |

| Scikit- Optimize | 0.9242 | 0.9270 | 0.9053 | 0.9150 | 0.8877 | 0.8869 | 0.9684 | 0.8848 | 0.0185 | −0.0394 | 50 |

| UCB | 0.9192 | 0.9203 | 0.9004 | 0.9084 | 0.8805 | 0.8792 | 0.9753 | 0.8684 | 0.0152 | −0.0508 | 50 |

| FLAML | 0.9141 | 0.9083 | 0.8964 | 0.9015 | 0.8728 | 0.8722 | 0.9686 | 0.8810 | 0.0194 | −0.0331 | 1069 |

| Grid Search | 0.9141 | 0.9106 | 0.8950 | 0.9020 | 0.8727 | 0.8721 | 0.9701 | 0.8835 | 0.0206 | −0.0306 | 540 |

| Hyperopt | 0.9141 | 0.9106 | 0.8950 | 0.9020 | 0.8727 | 0.8721 | 0.9709 | 0.8797 | 0.0144 | −0.0344 | 50 |

| Successive Halving | 0.9141 | 0.9103 | 0.9076 | 0.9083 | 0.8731 | 0.8728 | 0.9688 | 0.8620 | 0.0074 | −0.0521 | 72 |

| H2O AutoML | 0.9091 | 0.9052 | 0.8904 | 0.8963 | 0.8654 | 0.8644 | 0.9714 | 0.9608 | 0.0062 | 0.0517 | 16 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 0.9091 | 0.9051 | 0.8951 | 0.8984 | 0.8656 | 0.8647 | 0.9670 | 0.8620 | 0.0157 | −0.0471 | 56 |

| PSO | 0.9091 | 0.9045 | 0.8924 | 0.8976 | 0.8654 | 0.8649 | 0.9697 | 0.8797 | 0.0212 | −0.0293 | 60 |

| ASHA | 0.8990 | 0.8952 | 0.8849 | 0.8882 | 0.8505 | 0.8496 | 0.9670 | 0.8608 | 0.0170 | −0.0382 | 50 |

| Hyperband | 0.8990 | 0.8903 | 0.8836 | 0.8860 | 0.8505 | 0.8500 | 0.9679 | 0.8772 | 0.0095 | −0.0218 | 50 |

| Differential Evolution | 0.8990 | 0.8969 | 0.8773 | 0.8863 | 0.8500 | 0.8492 | 0.9780 | 0.8772 | 0.0218 | −0.0218 | 60 |

| Auto-sklearn | 0.8939 | 0.8840 | 0.8859 | 0.8839 | 0.8440 | 0.8436 | 0.9621 | 0.9165 | 0.0303 | 0.0225 | 283 |

| BOHB | 0.8889 | 0.8799 | 0.8734 | 0.8758 | 0.8354 | 0.8350 | 0.9646 | 0.8582 | 0.0182 | −0.0307 | 50 |

| CMA-ES | 0.8889 | 0.8799 | 0.8734 | 0.8758 | 0.8354 | 0.8350 | 0.9662 | 0.8658 | 0.0217 | −0.0231 | 50 |

| MAB | 0.8838 | 0.8734 | 0.8707 | 0.8714 | 0.8281 | 0.8279 | 0.9649 | 0.8696 | 0.0239 | −0.0142 | 50 |

| Thompson Sampling | 0.8838 | 0.8734 | 0.8707 | 0.8714 | 0.8281 | 0.8279 | 0.9649 | 0.8696 | 0.0239 | −0.0142 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Lan, B.; Liao, Z.; Zhao, D.; Hou, M. Bayesian-Optimized Explainable AI for CKD Risk Stratification: A Dual-Validated Framework. Symmetry 2026, 18, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010081

Huang J, Lan B, Liao Z, Zhao D, Hou M. Bayesian-Optimized Explainable AI for CKD Risk Stratification: A Dual-Validated Framework. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jianbo, Bitie Lan, Zhicheng Liao, Donghui Zhao, and Mengdi Hou. 2026. "Bayesian-Optimized Explainable AI for CKD Risk Stratification: A Dual-Validated Framework" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010081

APA StyleHuang, J., Lan, B., Liao, Z., Zhao, D., & Hou, M. (2026). Bayesian-Optimized Explainable AI for CKD Risk Stratification: A Dual-Validated Framework. Symmetry, 18(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010081