Statistical Estimation of Common Percentile in Birnbaum–Saunders Distributions: Insights from PM2.5 Data in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Common Percentile

2.1. Generalized Confidence Interval Approach

| Algorithm 1 GCI |

|

2.2. Bootstrap Approach

| Algorithm 2 Bootstrap CI |

|

2.3. Bayesian Approach

| Algorithm 3 Bayesian credible interval and HPD interval |

|

2.4. Highest Posterior Density Approach

3. Results

| Algorithm 4 CPs and ALs |

|

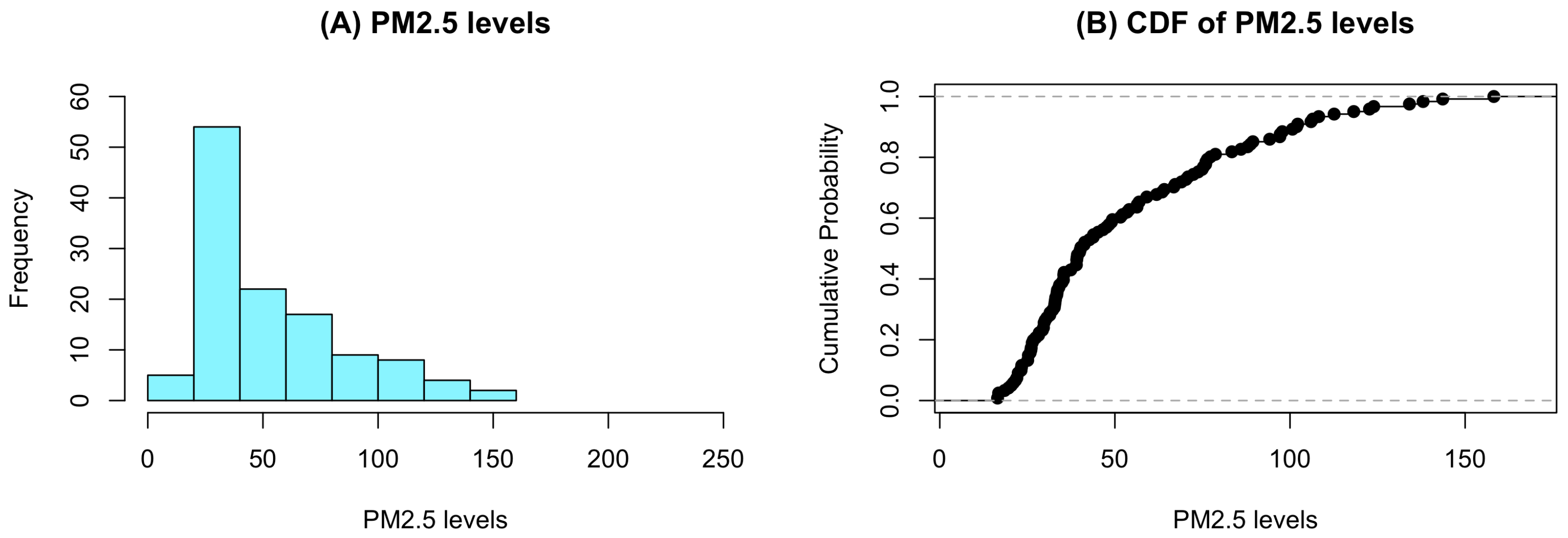

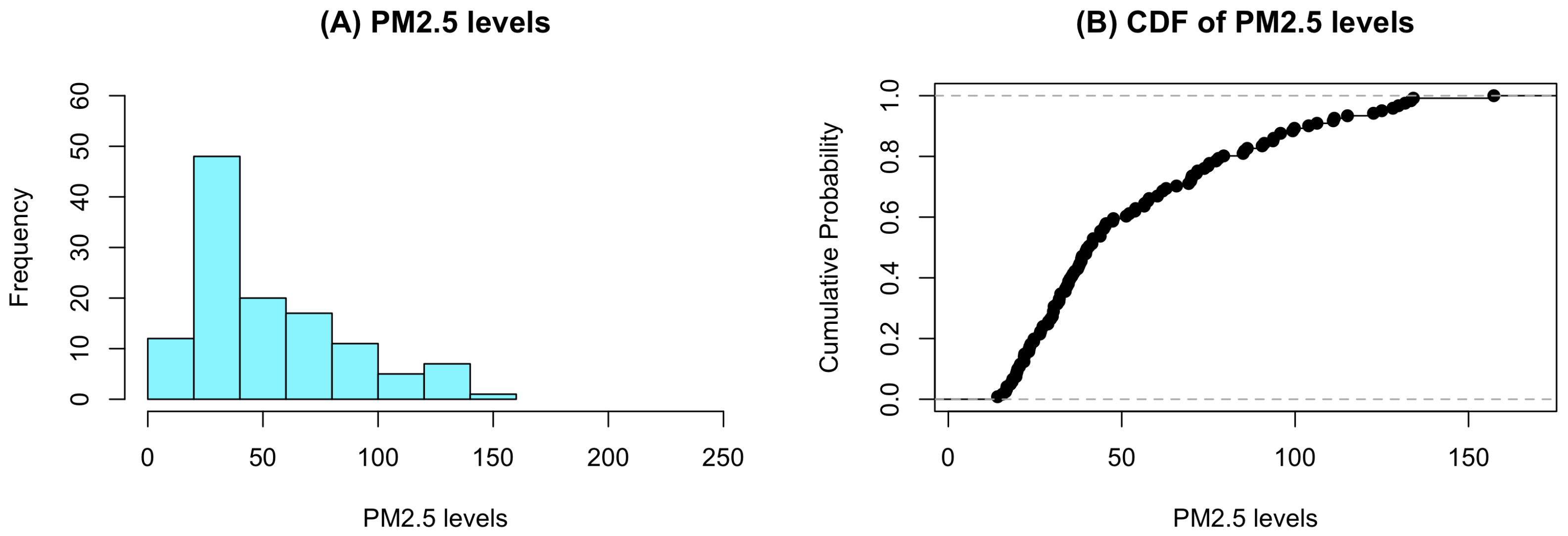

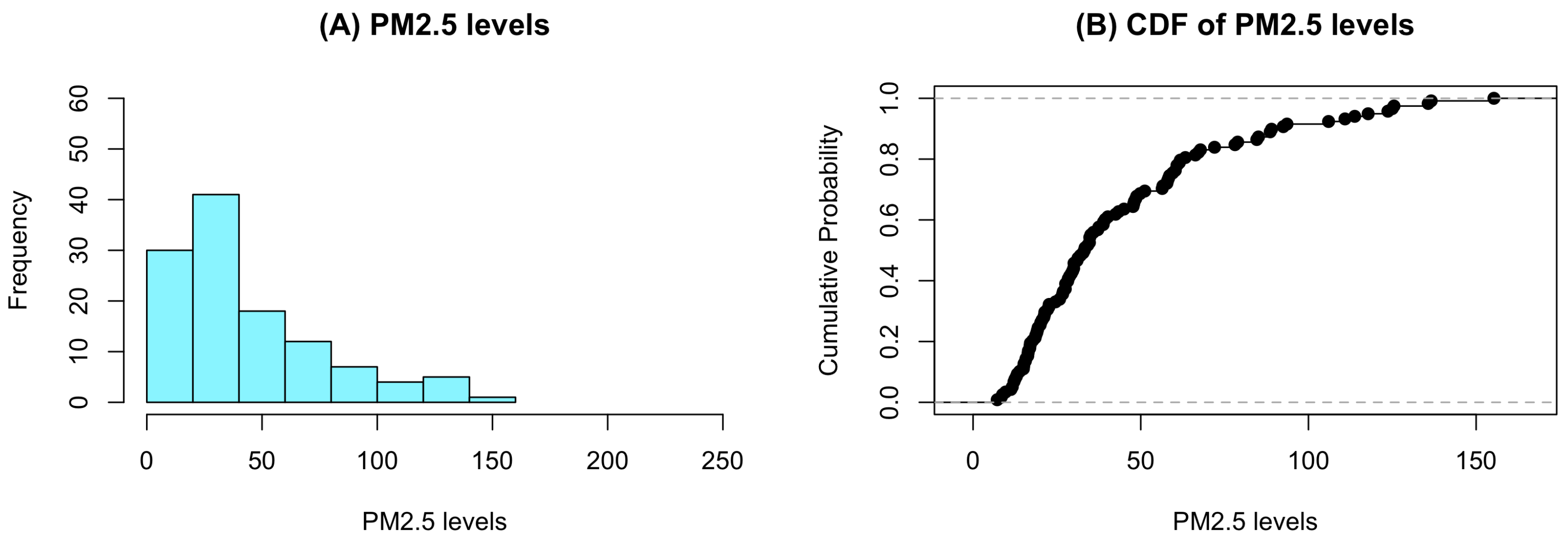

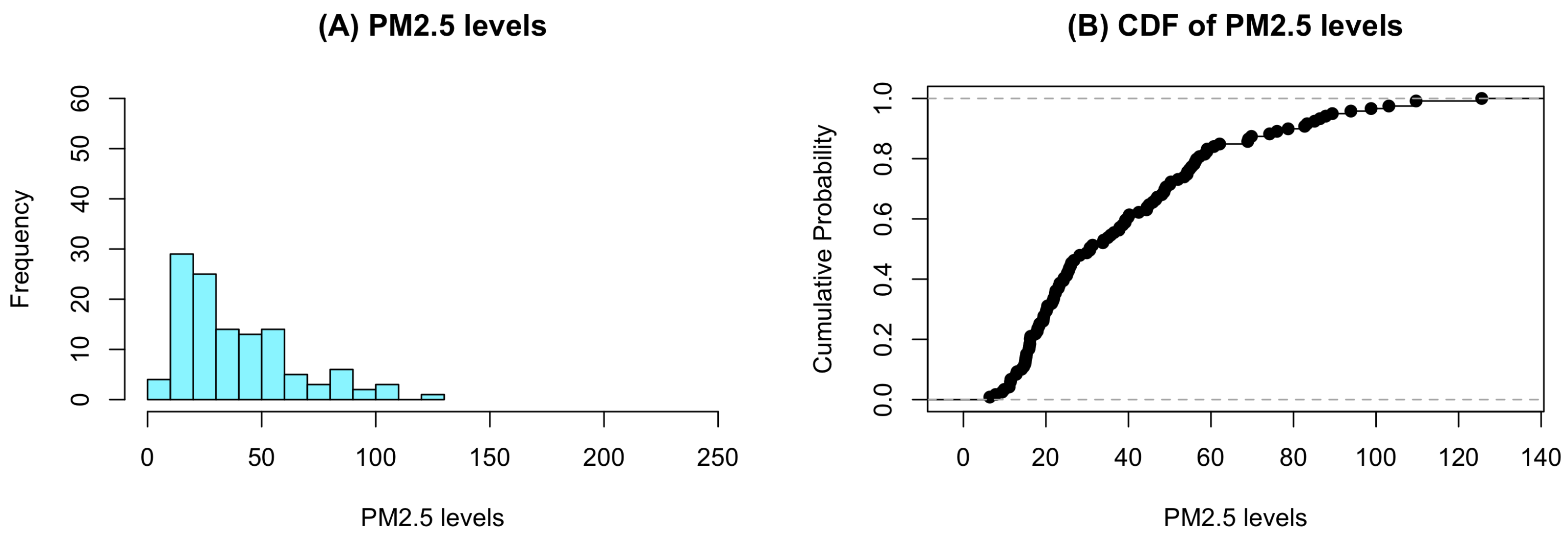

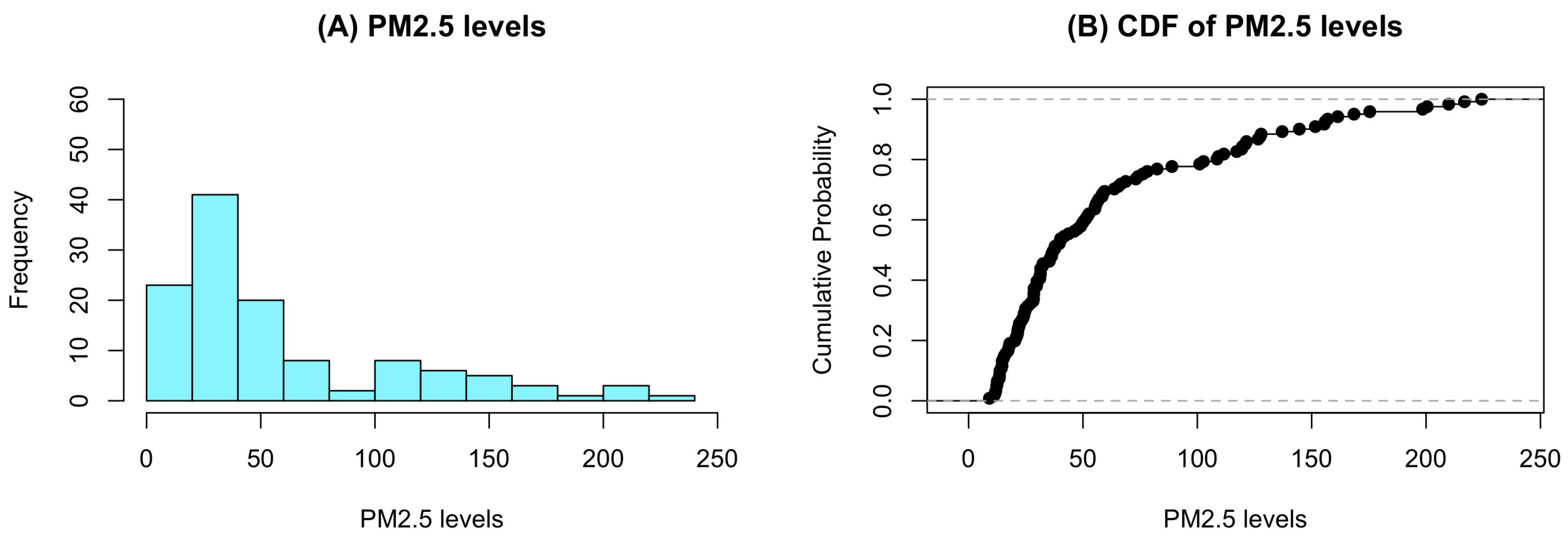

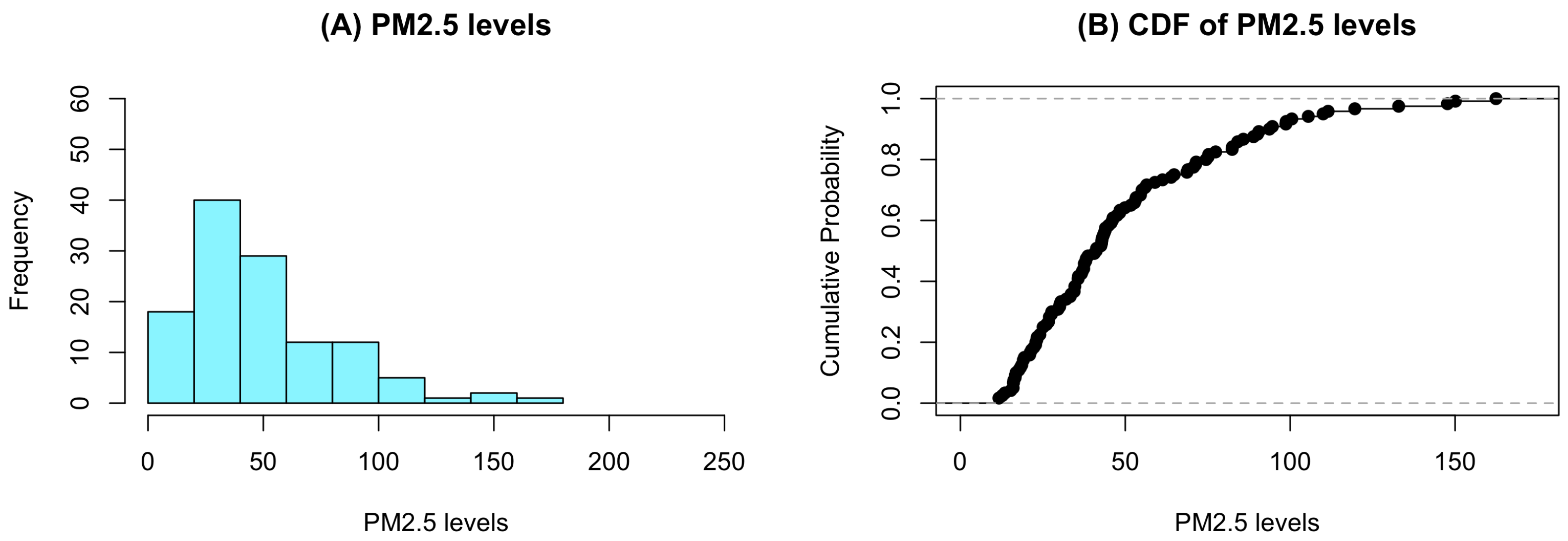

4. An Empirical Application

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Marshall, A.W.; Walsh, J.E. Some test for comparing percentage points of two arbitrary continuous populations. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1950; Volume I, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, F.E.; Davis, C.E. A new distribution-free quantile estimator. Biometrika 1982, 69, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaigh, W.D.; Lachenbruch, P.A. A generalized quantile estimator. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1982, 11, 2217–2238. [Google Scholar]

- Albers, W.; Löhnberg, P. An approximate confidence interval for the difference between quantiles in a biomedical problem. Stat. Neerl. 1984, 38, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.F.; Jaber, K. Testing the equality of two normal percentiles. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 1985, 14, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, D.S.; Tang, L.C. Percentile bounds and tolerance limits for the Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1994, 23, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, W.J.; Tomlinson, M.A. Lower confidence bounds for percentiles of Weibull and Birnbaum–Saunders distributions. J. Stat. Comput. Sim. 2003, 73, 429–443. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Krishnamoorthy, K. Comparison between two quantiles: The normal and exponential cases. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2005, 34, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-F.; Johnson, R.A. Confidence regions for the ratio of percentiles. Statist. Probab. Lett. 2006, 76, 384–392. [Google Scholar]

- Navruz, G.; Özdemir, A.F. Quantile estimation and comparing two independent groups with an approach based on percentile bootstrap. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2018, 47, 2119–2138. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.S.; Krishnamoorthy, K. Confidence intervals for the mean and a percentile based on zero-inflated lognormal data. J. Stat. Comput. Sim. 2018, 88, 1499–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahnezhad, K.; Jafari, A.A. Testing the equality of quantiles for several normal populations. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2018, 47, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Wu, H.; Li, G.; Li, Q. Inference for the common mean of several Birnbaum–Saunders populations. J. Appl. Stat. 2017, 44, 941–954. [Google Scholar]

- Shakil, M.; Munir, M.; Kausar, N.; Ahsanullah, M.; Khadim, A.; Sirajo, M.; Singh, J.N.; Kibria, M.G. Some inferences on three parameters Birnbaum–Saunders distribution: Statistical properties, characterizations and applications. Comput. J. Math. Stat. Sci. 2023, 2, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangjai, W.; Niwitpong, S.-A.; Niwitpong, S. Generalized confidence interval for the difference between percentiles of Birnbaum–Saunders distributions and its application to PM2.5 in Thailand. Comput. Math. Methods 2024, 2024, 2599243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, V.; Barros, M.; Paula, G.A.; Sanhueza, A. Generalized Birnbaum–Saunders distributions applied to air pollutant concentration. Environmetrics 2008, 19, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X. Generalized interval estimation for the Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2012, 56, 4320–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Guo, X.; Xu, W.; Zhu, L. Comparison of several Birnbaum–Saunders distributions. J. Stat. Comput. Simulation 2014, 84, 2721–2733. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.L. The confidence intervals for the scale parameter of the Birnbaum–Saunders fatigue life distribution. Acta Armament 2009, 30, 1558–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Sun, X.; Park, C. Bayesian analysis of Birnbaum–Saunders distribution via the generalized ratio-of-uniforms method. Comput. Stat. 2016, 31, 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, J.C.; Gelfand, A.E.; Smith, A.F.M. Efficient generation of random variates via the ratio-of-uniforms method. Stat. Comp. 1991, 1, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.D.; Ma, T.F.; Wang, S.G. Inferences on the common mean of several inverse Gaussian populations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2010, 54, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.; Jay, P. The causal effect of delivery volume on severe maternal morbidity: An instrumental variable analysis in Sichuan, China. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e8428. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Wang, R.; Lu, S.; Tian, J.; Yin, L.; Wang, L.; Zheng, W. Time-series data-driven PM2.5 forecasting: From theoretical framework to empirical analysis. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liang, L.; Lyu, B.; Cai, Y.S.; Zuo, Y.; Su, J.; Tong, Z. Double trouble: The interaction PM2.5 and O3 on respiratory hospital admissions. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 338, 122665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Cui, H.; Qi, H. Statistical analysis for estimating the optimized battery capacity for roof-top PV energy system. Renew. Energy 2025, 242, 122491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, S.P.; Chen, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Du, S. Reliability estimation method based on nonlinear Tweedie exponential dispersion process and evidential reasoning rule. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 206, 111205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CP (AL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10, 10, 10) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9382 | 0.8874 | 0.9270 | 0.9188 |

| (0.1926) | (0.1694) | (0.1849) | (0.1822) | ||

| (0.25, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9510 | 0.9096 | 0.9450 | 0.9410 | |

| (0.2881) | (0.2396) | (0.2745) | (0.2691) | ||

| (0.25, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9432 | 0.9166 | 0.9366 | 0.9324 | |

| (0.4762) | (0.3841) | (0.4483) | (0.4367) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9552 | 0.9146 | 0.9454 | 0.9470 | |

| (0.3021) | (0.2462) | (0.2871) | (0.2827) | ||

| (0.50, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9474 | 0.9152 | 0.9402 | 0.9342 | |

| (0.3843) | (0.3092) | (0.3632) | (0.3578) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9226 | 0.8910 | 0.9204 | 0.9160 | |

| (0.3279) | (0.2576) | (0.3098) | (0.3066) | ||

| (10, 30, 30) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9414 | 0.9154 | 0.9386 | 0.9316 |

| (0.1192) | (0.1136) | (0.1171) | (0.1159) | ||

| (0.25, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9420 | 0.9170 | 0.9368 | 0.9310 | |

| (0.1837) | (0.1720) | (0.1805) | (0.1788) | ||

| (0.25, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9514 | 0.9328 | 0.9466 | 0.9398 | |

| (0.2723) | (0.2507) | (0.2648) | (0.2625) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9494 | 0.9336 | 0.9448 | 0.9438 | |

| (0.1787) | (0.1622) | (0.1739) | (0.1720) | ||

| (0.50, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9482 | 0.9364 | 0.9468 | 0.9430 | |

| (0.2089) | (0.1887) | (0.2023) | (0.2005) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9416 | 0.9168 | 0.9374 | 0.9436 | |

| (0.2104) | (0.1732) | (0.1988) | (0.1954) | ||

| (30, 30, 30) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9454 | 0.9274 | 0.9394 | 0.9370 |

| (0.1034) | (0.0998) | (0.1019) | (0.1009) | ||

| (0.25, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9420 | 0.9314 | 0.9406 | 0.9382 | |

| (0.1491) | (0.1416) | (0.1470) | (0.1456) | ||

| (0.25, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9462 | 0.9352 | 0.9442 | 0.9408 | |

| (0.2480) | (0.2259) | (0.2399) | (0.2367) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9536 | 0.9434 | 0.9512 | 0.9472 | |

| (0.1514) | (0.1423) | (0.1489) | (0.1475) | ||

| (0.50, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9510 | 0.9374 | 0.9474 | 0.9486 | |

| (0.2001) | (0.1807) | (0.1934) | (0.1914) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9428 | 0.9250 | 0.9390 | 0.9386 | |

| (0.1669) | (0.1477) | (0.1611) | (0.1597) | ||

| (30, 50, 50) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9466 | 0.9356 | 0.9462 | 0.9430 |

| (0.0853) | (0.0832) | (0.0844) | (0.0836) | ||

| (0.25, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9518 | 0.9400 | 0.9498 | 0.9480 | |

| (0.1275) | (0.1231) | (0.1260) | (0.1249) | ||

| (0.25, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9512 | 0.9454 | 0.9510 | 0.9446 | |

| (0.2003) | (0.1889) | (0.1955) | (0.1937) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9518 | 0.9454 | 0.9502 | 0.9478 | |

| (0.1236) | (0.1183) | (0.1221) | (0.1210) | ||

| (0.50, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9530 | 0.9446 | 0.9522 | 0.9472 | |

| (0.1537) | (0.1434) | (0.1497) | (0.1484) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9480 | 0.9340 | 0.9400 | 0.9410 | |

| (0.1346) | (0.1221) | (0.1304) | (0.1293) | ||

| (50, 50, 50) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9484 | 0.9376 | 0.9456 | 0.9422 |

| (0.0791) | (0.0775) | (0.0783) | (0.0776) | ||

| (0.25, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9546 | 0.94920 | 0.9520 | 0.9492 | |

| (0.1137) | (0.1102) | (0.1127) | (0.1116) | ||

| (0.25, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9502 | 0.9410 | 0.9448 | 0.9428 | |

| (0.1867) | (0.1752) | (0.1818) | (0.1799) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9490 | 0.9434 | 0.9462 | 0.9440 | |

| (0.1144) | (0.1102) | (0.1132) | (0.1122) | ||

| (0.50, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9506 | 0.9426 | 0.9490 | 0.9460 | |

| (0.1499) | (0.1397) | (0.1458) | (0.1445) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9436 | 0.9358 | 0.9434 | 0.9418 | |

| (0.1233) | (0.1133) | (0.1199) | (0.1189) | ||

| (50, 100, 100) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9486 | 0.9404 | 0.9442 | 0.9402 |

| (0.0608) | (0.0599) | (0.0604) | (0.0598) | ||

| (0.25, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9516 | 0.9428 | 0.9484 | 0.9450 | |

| (0.0915) | (0.0899) | (0.0907) | (0.0900) | ||

| (0.25, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9482 | 0.9412 | 0.9464 | 0.9430 | |

| (0.1408) | (0.1359) | (0.1381) | (0.1370) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9538 | 0.9460 | 0.9478 | 0.9468 | |

| (0.0874) | (0.0852) | (0.0867) | (0.0859) | ||

| (0.50, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9504 | 0.9440 | 0.9484 | 0.9448 | |

| (0.1060) | (0.1015) | (0.1037) | (0.1029) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9454 | 0.9382 | 0.9452 | 0.9422 | |

| (0.0928) | (0.0872) | (0.0905) | (0.0898) | ||

| (100, 100, 100) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9482 | 0.9420 | 0.9452 | 0.9426 |

| (0.0555) | (0.0548) | (0.0551) | (0.0546) | ||

| (0.25, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9496 | 0.9456 | 0.9458 | 0.9448 | |

| (0.0797) | (0.0783) | (0.0791) | (0.0784) | ||

| (0.25, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9438 | 0.9408 | 0.9420 | 0.9390 | |

| (0.1280) | (0.1232) | (0.1254) | (0.1242) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9508 | 0.9418 | 0.9454 | 0.9416 | |

| (0.0795) | (0.0778) | (0.0789) | (0.0782) | ||

| (0.50, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9470 | 0.9402 | 0.9450 | 0.9436 | |

| (0.1026) | (0.0980) | (0.1004) | (0.0995) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9474 | 0.9446 | 0.9484 | 0.9458 | |

| (0.0837) | (0.0793) | (0.0818) | (0.0812) | ||

| CP (AL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9332 | 0.8564 | 0.9158 | 0.9084 |

| (0.1375) | (0.1246) | (0.1320) | (0.1305) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9478 | 0.9004 | 0.9408 | 0.9354 | |

| (0.2000) | (0.1678) | (0.1894) | (0.1857) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9458 | 0.9206 | 0.9426 | 0.9574 | |

| (0.4280) | (0.3097) | (0.3867) | (0.3631) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9412 | 0.9094 | 0.9376 | 0.9420 | |

| (0.2310) | (0.1807) | (0.2170) | (0.2130) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9166 | 0.8806 | 0.9170 | 0.9336 | |

| (0.3499) | (0.2558) | (0.3223) | (0.3120) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.8470 | 0.7690 | 0.8494 | 0.8696 | |

| (0.2808) | (0.1936) | (0.2596) | (0.2548) | ||

| (10, 10, 10, 30, 30, 30) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9376 | 0.8996 | 0.9292 | 0.9236 |

| (0.0925) | (0.0885) | (0.0905) | (0.0896) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9466 | 0.9046 | 0.9408 | 0.9346 | |

| (0.1434) | (0.1348) | (0.1405) | (0.1392) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9580 | 0.9358 | 0.9566 | 0.9498 | |

| (0.2346) | (0.2123) | (0.2270) | (0.2245) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9494 | 0.9332 | 0.9444 | 0.9462 | |

| (0.1456) | (0.1264) | (0.1399) | (0.1380) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9474 | 0.9326 | 0.9436 | 0.9428 | |

| (0.1801) | (0.1571) | (0.1731) | (0.1714) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.8802 | 0.8256 | 0.8786 | 0.9142 | |

| (0.2012) | (0.1417) | (0.1820) | (0.1754) | ||

| (30, 30, 30, 30, 30, 30) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9416 | 0.9234 | 0.9370 | 0.9316 |

| (0.0732) | (0.0713) | (0.0722) | (0.0716) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9436 | 0.9314 | 0.9416 | 0.9390 | |

| (0.0990) | (0.0950) | (0.0975) | (0.0966) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9476 | 0.9416 | 0.9468 | 0.9528 | |

| (0.1759) | (0.1569) | (0.1687) | (0.1653) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9504 | 0.9408 | 0.9470 | 0.9438 | |

| (0.1084) | (0.1015) | (0.1066) | (0.1056) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9376 | 0.9240 | 0.9344 | 0.9442 | |

| (0.1562) | (0.1373) | (0.1501) | (0.1479) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9042 | 0.8760 | 0.9020 | 0.9094 | |

| (0.1258) | (0.1062) | (0.1205) | (0.1192) | ||

| (30, 30, 30, 50, 50, 50) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9464 | 0.9318 | 0.9436 | 0.9416 |

| (0.0629) | (0.0616) | (0.0622) | (0.0617) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9468 | 0.9298 | 0.9422 | 0.9376 | |

| (0.0898) | (0.0872) | (0.0889) | (0.0881) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9544 | 0.9470 | 0.9510 | 0.9500 | |

| (0.1509) | (0.1408) | (0.1465) | (0.1449) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9404 | 0.9332 | 0.9382 | 0.9382 | |

| (0.0922) | (0.0877) | (0.0909) | (0.0901) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9480 | 0.9404 | 0.9456 | 0.9448 | |

| (0.1235) | (0.1133) | (0.1198) | (0.1187) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9100 | 0.8888 | 0.9086 | 0.9140 | |

| (0.1050) | (0.0913) | (0.1010) | (0.1000) | ||

| (50, 50, 50, 50, 50, 50) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9490 | 0.9394 | 0.9450 | 0.9394 |

| (0.0559) | (0.0550) | (0.0554) | (0.0549) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9456 | 0.9390 | 0.9418 | 0.9408 | |

| (0.0749) | (0.0731) | (0.0741) | (0.0734) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9470 | 0.9404 | 0.9464 | 0.9490 | |

| (0.1262) | (0.1175) | (0.1224) | (0.1208) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9536 | 0.9432 | 0.9496 | 0.9476 | |

| (0.0815) | (0.0784) | (0.0806) | (0.0799) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9446 | 0.9348 | 0.9442 | 0.9460 | |

| (0.1137) | (0.1045) | (0.1102) | (0.1090) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9158 | 0.8966 | 0.9132 | 0.9140 | |

| (0.0903) | (0.0809) | (0.0874) | (0.0867) | ||

| (50, 50, 50, 100, 100, 100) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9450 | 0.9370 | 0.9430 | 0.9406 |

| (0.0454) | (0.0449) | (0.0451) | (0.0447) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9506 | 0.9470 | 0.9476 | 0.9466 | |

| (0.0658) | (0.0647) | (0.0652) | (0.0647) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9560 | 0.9508 | 0.9568 | 0.9532 | |

| (0.1066) | (0.1024) | (0.1044) | (0.1035) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9464 | 0.9420 | 0.9456 | 0.9432 | |

| (0.0656) | (0.0637) | (0.0650) | (0.0645) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9450 | 0.9432 | 0.9474 | 0.9450 | |

| (0.0851) | (0.0808) | (0.0832) | (0.0825) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9282 | 0.9200 | 0.9288 | 0.9296 | |

| (0.0713) | (0.0656) | (0.0692) | (0.0686) | ||

| (100, 100, 100, 100, 100, 100) | (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25) | 0.9534 | 0.9452 | 0.9520 | 0.9492 |

| (0.0392) | (0.0388) | (0.0389) | (0.0386) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9466 | 0.9416 | 0.9438 | 0.9434 | |

| (0.0521) | (0.0514) | (0.0517) | (0.0513) | ||

| (0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9482 | 0.9428 | 0.9458 | 0.9464 | |

| (0.0845) | (0.0811) | (0.0827) | (0.0818) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50) | 0.9470 | 0.9428 | 0.9436 | 0.9398 | |

| (0.0564) | (0.0552) | (0.0559) | (0.0555) | ||

| (0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9470 | 0.9442 | 0.9474 | 0.9484 | |

| (0.0762) | (0.0725) | (0.0743) | (0.0737) | ||

| (1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00) | 0.9338 | 0.9252 | 0.9348 | 0.9326 | |

| (0.0601) | (0.0563) | (0.0587) | (0.0582) | ||

| Stations | PM2.5 Levels | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station 1 | 25.1 | 21.6 | 20.4 | 22.4 | 25.3 | 25.3 | 23.2 | 29.6 | 31.5 | 25.8 |

| 26.4 | 22.4 | 21.0 | 23.3 | 35.5 | 29.8 | 26.7 | 23.4 | 22.0 | 18.5 | |

| 16.5 | 25.1 | 27.4 | 29.3 | 35.4 | 34.2 | 33.4 | 32.8 | 32.9 | 33.5 | |

| 28.4 | 19.6 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 33.0 | 39.1 | 32.2 | 28.2 | 31.4 | 39.0 | |

| 39.0 | 45.2 | 40.1 | 39.2 | 35.3 | 34.0 | 32.7 | 37.4 | 34.9 | 26.1 | |

| 30.6 | 26.4 | 26.0 | 43.9 | 35.4 | 29.8 | 33.1 | 54.1 | 56.3 | 48.3 | |

| 39.9 | 47.6 | 42.7 | 40.3 | 39.1 | 63.5 | 86.0 | 101.9 | 70.3 | 56.9 | |

| 66.8 | 64.1 | 51.6 | 56.4 | 118.2 | 143.6 | 106.0 | 88.7 | 112.6 | 97.2 | |

| 30.1 | 33.6 | 39.3 | 41.4 | 59.1 | 53.5 | 75.9 | 67.2 | 77.3 | 75.3 | |

| 97.1 | 87.9 | 100.7 | 108.2 | 123.9 | 106.5 | 134.1 | 158.2 | 138.0 | 122.7 | |

| 102.2 | 46.6 | 41.2 | 43.8 | 52.2 | 61.9 | 49.3 | 49.0 | 76.4 | 97.8 | |

| 89.4 | 72.4 | 59.1 | 73.8 | 69.0 | 70.9 | 94.2 | 78.7 | 76.0 | 74.9 | |

| 83.4 | ||||||||||

| Station 2 | 28.7 | 19.8 | 18.6 | 18.4 | 21.8 | 20.5 | 19.5 | 26.6 | 27.3 | 23.3 |

| 20.8 | 22.0 | 24.6 | 20.0 | 32.4 | 24.7 | 21.9 | 17.9 | 19.6 | 15.6 | |

| 16.9 | 23.2 | 28.9 | 30.5 | 37.9 | 33.7 | 29.5 | 30.3 | 34.7 | 27.3 | |

| 23.8 | 14.2 | 16.8 | 16.5 | 32.4 | 43.9 | 33.8 | 31.4 | 30.3 | 43.9 | |

| 38.3 | 32.0 | 30.5 | 39.6 | 30.0 | 35.6 | 31.9 | 38.4 | 34.2 | 23.5 | |

| 26.4 | 21.9 | 26.4 | 38.6 | 37.3 | 35.1 | 34.6 | 51.3 | 54.0 | 45.2 | |

| 41.4 | 53.8 | 45.5 | 41.8 | 40.0 | 62.8 | 103.9 | 115.1 | 90.5 | 57.9 | |

| 69.9 | 74.9 | 52.2 | 56.6 | 122.6 | 133.4 | 106.3 | 91.1 | 125.0 | 85.0 | |

| 37.6 | 36.0 | 40.6 | 43.8 | 65.8 | 57.5 | 93.6 | 70.1 | 71.9 | 85.4 | |

| 95.8 | 93.8 | 99.8 | 111.3 | 134.1 | 111.0 | 131.7 | 157.3 | 128.2 | 129.8 | |

| 99.3 | 41.8 | 36.5 | 39.7 | 44.8 | 60.3 | 47.6 | 47.4 | 75.3 | 86.2 | |

| 95.8 | 77.9 | 56.5 | 70.3 | 61.8 | 61.8 | 77.2 | 73.8 | 71.5 | 69.3 | |

| 79.4 | ||||||||||

| Station 3 | 12.2 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 13.9 | 15.2 | 15.0 | 22.2 | 21.4 | 17.0 | 15.8 |

| 13.2 | 12.5 | 20.2 | 24.6 | 19.4 | 16.9 | 16.4 | 12.9 | 9.7 | 8.8 | |

| 15.6 | 19.2 | 26.7 | 28.4 | 25.8 | 16.5 | 22.7 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 15.1 | |

| 8.4 | 7.2 | 12.2 | 31.3 | 27.5 | 21.3 | 20.6 | 26.9 | 30.1 | 35.1 | |

| 37.2 | 33.4 | 32.8 | 28.2 | 30.0 | 29.7 | 38.8 | 27.6 | 16.3 | 18.7 | |

| 17.1 | 21.1 | 34.8 | 22.6 | 17.8 | 28.8 | 48.8 | 56.4 | 39.4 | 33.2 | |

| 38.9 | 31.0 | 32.0 | 34.2 | 66.3 | 84.6 | 88.6 | 48.1 | 48.5 | 43.4 | |

| 34.7 | 34.8 | 58.3 | 136.6 | 125.0 | 89.0 | 72.0 | 93.6 | 18.5 | 26.7 | |

| 30.1 | 37.5 | 47.9 | 49.8 | 67.8 | 60.3 | 78.9 | 56.6 | 92.5 | 88.6 | |

| 117.8 | 106.0 | 113.8 | 110.9 | 123.7 | 155.3 | 135.7 | 125.5 | 85.1 | 29.3 | |

| 27.6 | 35.9 | 45.0 | 51.2 | 40.2 | 47.7 | 60.8 | 78.1 | 60.8 | 42.5 | |

| 58.0 | 61.5 | 59.5 | 61.8 | 58.6 | 57.8 | 67.2 | 63.3 | |||

| Station 4 | 16.2 | 11.1 | 11.5 | 12.8 | 16.2 | 16.3 | 15.1 | 16.0 | 15.3 | 15.9 |

| 17.5 | 19.4 | 11.4 | 9.4 | 20.1 | 20.3 | 14.9 | 14.1 | 13.0 | 12.8 | |

| 11.4 | 21.4 | 22.3 | 20.4 | 18.3 | 26.8 | 21.7 | 16.1 | 22.3 | 22.4 | |

| 15.9 | 9.9 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 25.0 | 23.2 | 21.9 | 18.5 | 23.4 | 34.0 | |

| 26.2 | 25.2 | 33.8 | 25.5 | 17.9 | 19.3 | 15.2 | 24.4 | 26.0 | 14.6 | |

| 20.1 | 24.2 | 15.0 | 23.0 | 18.0 | 19.5 | 39.2 | 58.5 | 54.2 | 45.0 | |

| 48.6 | 59.1 | 38.6 | 30.6 | 28.2 | 42.5 | 50.3 | 54.3 | 35.0 | 44.5 | |

| 39.9 | 28.2 | 37.7 | 45.9 | 86.4 | 109.7 | 74.2 | 60.7 | 50.0 | 55.3 | |

| 25.7 | 31.3 | 36.5 | 48.8 | 62.1 | 44.4 | 56.2 | 53.5 | 68.9 | 69.8 | |

| 82.7 | 85.1 | 103.1 | 87.8 | 109.7 | 125.6 | 98.8 | 76.0 | 83.3 | 37.9 | |

| 29.9 | 30.7 | 40.2 | 39.3 | 35.7 | 57.2 | 78.7 | 89.4 | 93.9 | 69.1 | |

| 48.1 | 54.8 | 56.5 | 46.6 | 49.1 | 47.0 | 59.0 | 55.9 | 52.0 | ||

| Station 5 | 22.2 | 12.3 | 13.7 | 11.9 | 13.5 | 15.6 | 14.7 | 17.5 | 16.3 | 13.4 |

| 17.2 | 14.7 | 12.5 | 14.6 | 23.7 | 20.6 | 15.2 | 14.3 | 18.0 | 12.6 | |

| 12.3 | 13.7 | 21.1 | 21.4 | 31.2 | 28.4 | 28.5 | 20.2 | 24.3 | 22.1 | |

| 17.8 | 11.1 | 9.1 | 11.6 | 31.5 | 36.4 | 21.5 | 24.1 | 28.2 | 32.3 | |

| 35.3 | 36.9 | 24.7 | 29.9 | 25.9 | 28.5 | 31.4 | 29.7 | 21.7 | 23.0 | |

| 28.6 | 24.9 | 27.0 | 31.1 | 36.3 | 39.6 | 37.7 | 52.6 | 49.6 | 37.8 | |

| 31.5 | 43.7 | 40.0 | 35.5 | 40.2 | 88.9 | 127.5 | 157.0 | 101.0 | 56.4 | |

| 65.4 | 76.2 | 47.7 | 58.4 | 137.1 | 119.4 | 127.9 | 121.5 | 161.4 | 126.6 | |

| 32.5 | 29.8 | 28.6 | 41.8 | 51.2 | 73.1 | 117.2 | 111.6 | 121.0 | 119.7 | |

| 144.6 | 155.5 | 216.8 | 198.5 | 200.5 | 175.4 | 224.3 | 209.9 | 168.5 | 151.6 | |

| 155.9 | 55.2 | 50.3 | 55.2 | 55.8 | 58.5 | 49.0 | 46.2 | 74.1 | 63.7 | |

| 78.1 | 66.6 | 59.4 | 109.2 | 82.4 | 57.0 | 55.4 | 51.9 | 68.7 | 102.7 | |

| 108.6 | ||||||||||

| Station 6 | 25.1 | 16.6 | 17.7 | 16.1 | 18.2 | 21.6 | 23.3 | 25.1 | 21.0 | 16.7 |

| 16.9 | 15.3 | 16.0 | 19.1 | 22.9 | 22.8 | 19.1 | 16.2 | 16.1 | 12.7 | |

| 18.6 | 22.3 | 27.7 | 21.2 | 32.1 | 33.6 | 27.6 | 27.0 | 26.1 | 19.4 | |

| 11.7 | 11.7 | 13.5 | 23.2 | 35.8 | 27.0 | 26.7 | 29.6 | 38.7 | 33.3 | |

| 42.9 | 37.0 | 35.7 | 30.2 | 38.2 | 35.7 | 44.9 | 41.3 | 30.5 | 37.4 | |

| 37.6 | 35.7 | 43.3 | 55.1 | 75.1 | 82.4 | 70.7 | 69.0 | 45.7 | 36.7 | |

| 44.0 | 43.0 | 34.7 | 25.1 | 64.8 | 71.5 | 82.5 | 56.0 | 48.3 | 59.0 | |

| 48.4 | 42.6 | 37.6 | 98.7 | 147.7 | 110.0 | 88.9 | 68.7 | 63.9 | 24.1 | |

| 34.7 | 43.9 | 46.3 | 74.5 | 119.6 | 111.5 | 100.5 | 162.4 | 90.1 | 98.8 | |

| 85.8 | 90.5 | 84.1 | 93.7 | 84.1 | 132.9 | 150.1 | 105.5 | 75.3 | 94.6 | |

| 41.2 | 30.1 | 34.5 | 40.6 | 42.8 | 38.0 | 46.1 | 71.3 | 77.4 | 61.3 | |

| 52.8 | 53.1 | 54.6 | 51.7 | 49.9 | 43.6 | 47.5 | 56.5 | 53.3 | 55.1 | |

| Distributions | Stations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station 1 | Station 2 | Station 3 | Station 4 | Station 5 | Station 6 | |

| Normal distribution | 1185.18 | 1194.21 | 1161.23 | 1116.59 | 1306.07 | 1173.40 |

| Log-normal distribution | 1131.93 | 1142.06 | 1094.12 | 1066.78 | 1208.59 | 1119.85 |

| Weibull distribution | 1152.28 | 1158.75 | 1109.09 | 1077.35 | 1227.65 | 1134.86 |

| Gamma distribution | 1141.22 | 1149.88 | 1102.16 | 1071.23 | 1222.82 | 1126.03 |

| Exponential distribution | 1208.73 | 1206.87 | 1133.60 | 1113.57 | 1234.59 | 1178.89 |

| Logistic distribution | 1183.17 | 1193.52 | 1153.43 | 1114.26 | 1298.07 | 1166.23 |

| Cauchy distribution | 1201.46 | 1213.32 | 1162.79 | 1143.70 | 1286.95 | 1183.19 |

| Birnbaum–Saunders distribution | 1130.67 | 1140.47 | 1093.05 | 1065.69 | 1203.67 | 1119.53 |

| Statistics | Stations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station 1 | Station 2 | Station 3 | Station 4 | Station 5 | Station 6 | |

| 121 | 121 | 118 | 119 | 121 | 120 | |

| 0.6126 | 0.6575 | 0.7747 | 0.6911 | 0.9833 | 0.6593 | |

| 56.7104 | 55.5136 | 42.7081 | 30.7391 | 62.8481 | 47.8938 | |

| 26.3577 | 24.4623 | 16.4183 | 13.0209 | 19.1411 | 21.0598 | |

| 3.4907 | 3.4052 | 2.0795 | 1.0693 | 4.0161 | 2.5570 | |

| Approaches | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Length | |

| GCI | 15.2117 | 17.5398 | 2.3281 |

| Bootstrap | 15.3316 | 17.6617 | 2.3301 |

| Bayesian | 15.3155 | 17.6143 | 2.2988 |

| HPD | 15.2638 | 17.5398 | 2.2760 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thangjai, W.; Niwitpong, S.-A.; Niwitpong, S.; Prommai, R. Statistical Estimation of Common Percentile in Birnbaum–Saunders Distributions: Insights from PM2.5 Data in Thailand. Symmetry 2026, 18, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010100

Thangjai W, Niwitpong S-A, Niwitpong S, Prommai R. Statistical Estimation of Common Percentile in Birnbaum–Saunders Distributions: Insights from PM2.5 Data in Thailand. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleThangjai, Warisa, Sa-Aat Niwitpong, Suparat Niwitpong, and Rattana Prommai. 2026. "Statistical Estimation of Common Percentile in Birnbaum–Saunders Distributions: Insights from PM2.5 Data in Thailand" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010100

APA StyleThangjai, W., Niwitpong, S.-A., Niwitpong, S., & Prommai, R. (2026). Statistical Estimation of Common Percentile in Birnbaum–Saunders Distributions: Insights from PM2.5 Data in Thailand. Symmetry, 18(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010100