Research on Fault-Diagnosis Technology of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motor Based on Digital Twin

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We construct a high-fidelity digital twin model based on the five-dimensional model theory. This model serves as a virtual platform to simulate both the baseline symmetrical patterns of a healthy motor and the distinct asymmetries introduced by various faults, establishing a foundation for studying various fault scenarios, which are treated as symmetry-breaking phenomena, in a controlled environment.

- Making full use of the dynamics simulation capability of the digital twin virtual model, it parametrically adjusts the type and degree of faults, flexibly simulates a variety of fault scenarios, and generates diversified fault data that are highly related to the rare-earth permanent magnet motors, which mitigates the challenges of data scarcity, high cost of obtaining fault samples, and insufficient coverage of the actual working conditions in traditional fault diagnosis.

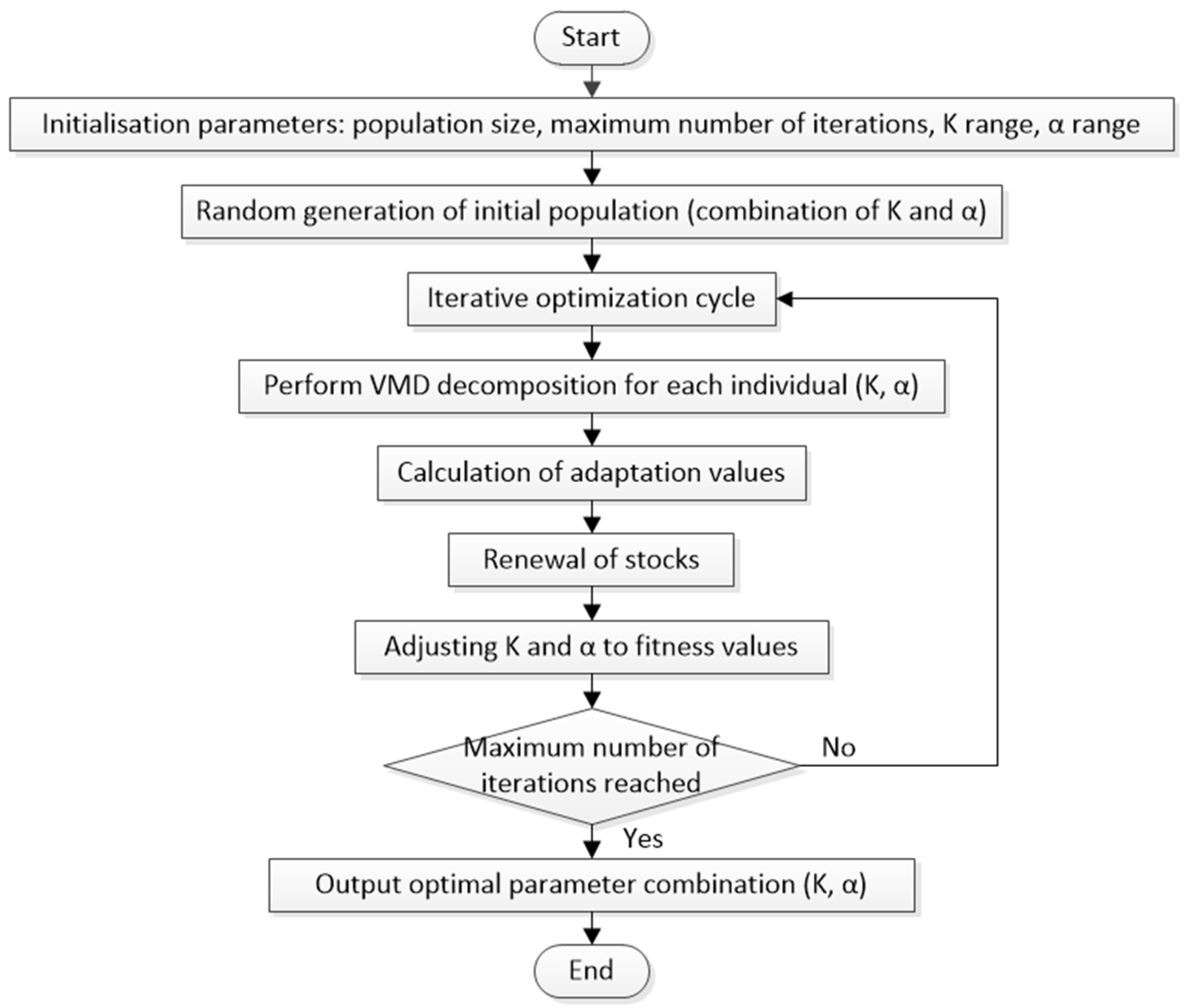

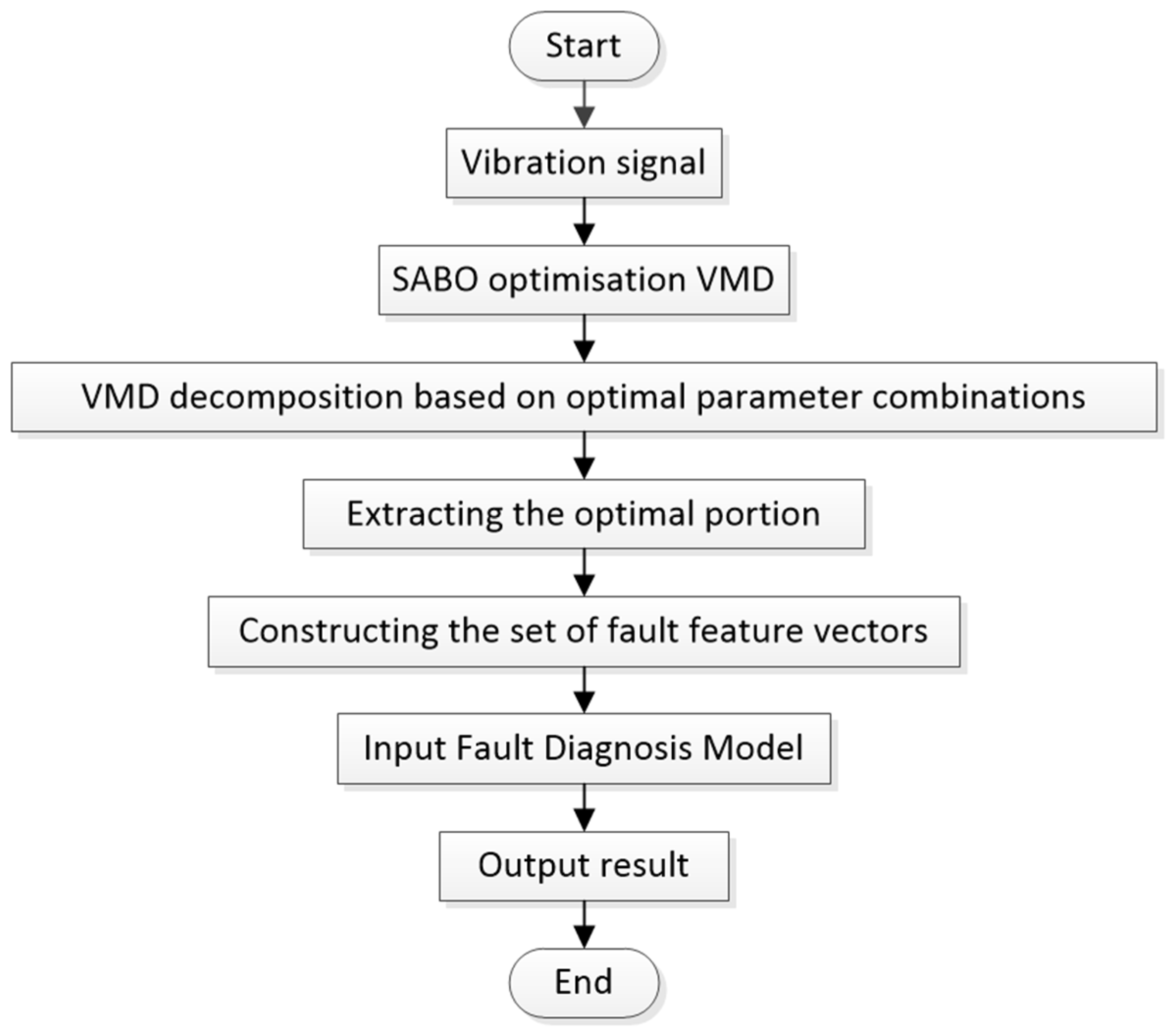

- Based on the deep integration of digital twin-based simulation data and machine learning-based fault-diagnosis technology, a subtractive optimizer algorithm is used to optimize the variational modal decomposition in the fault-feature extraction process. It can guide the variational modal decomposition to extract fault features more efficiently and accurately, avoiding the problems of incomplete or inaccurate feature extraction that may occur in other methods. Furthermore, in the fault identification stage, the convolutional bidirectional long and short-term memory network is introduced to solve the problem of the low accuracy of fault diagnosis of tiny faults by virtue of its powerful time series data processing capability and feature learning ability.

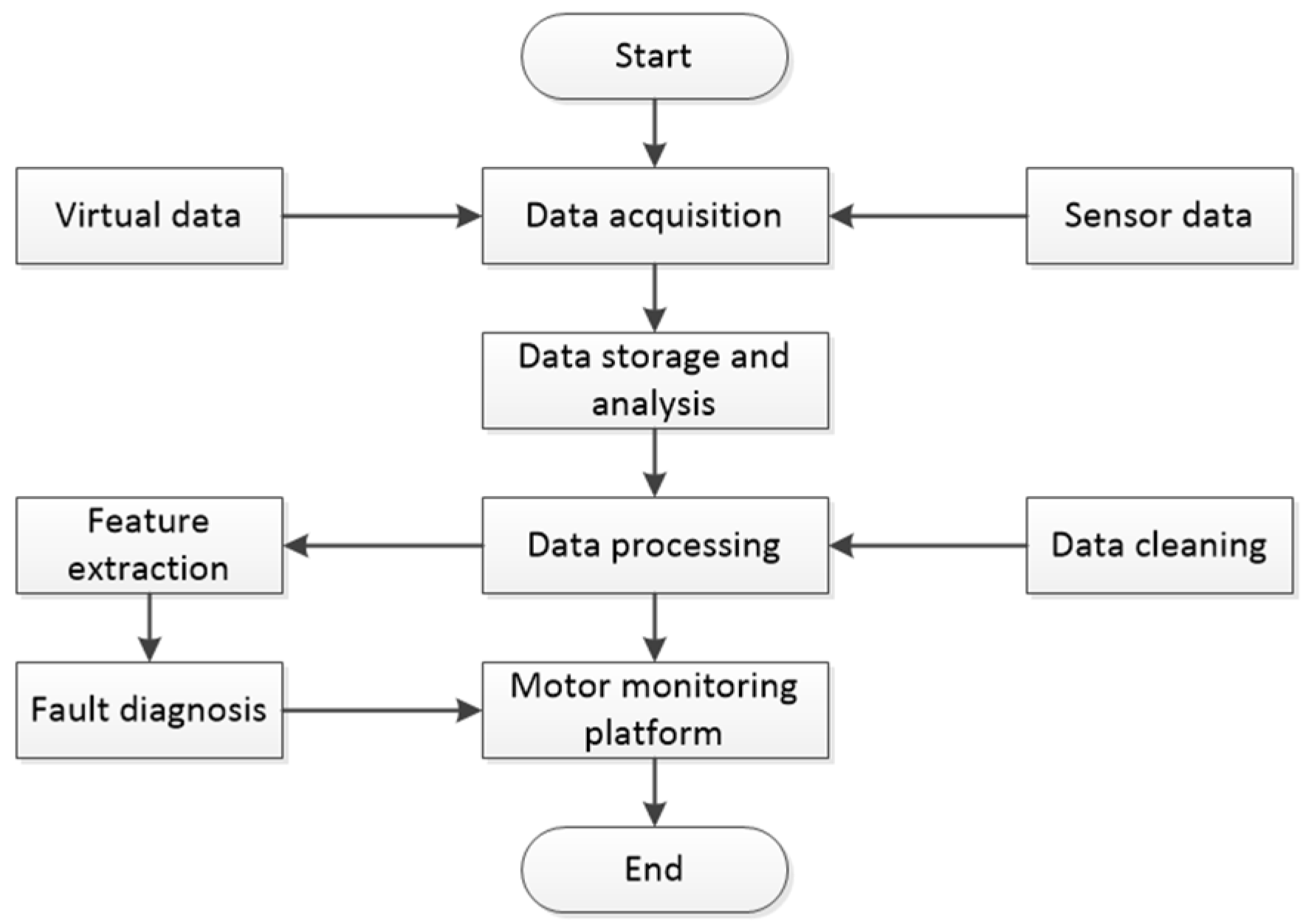

2. Digital Twin Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. Digital Twin Virtual Model

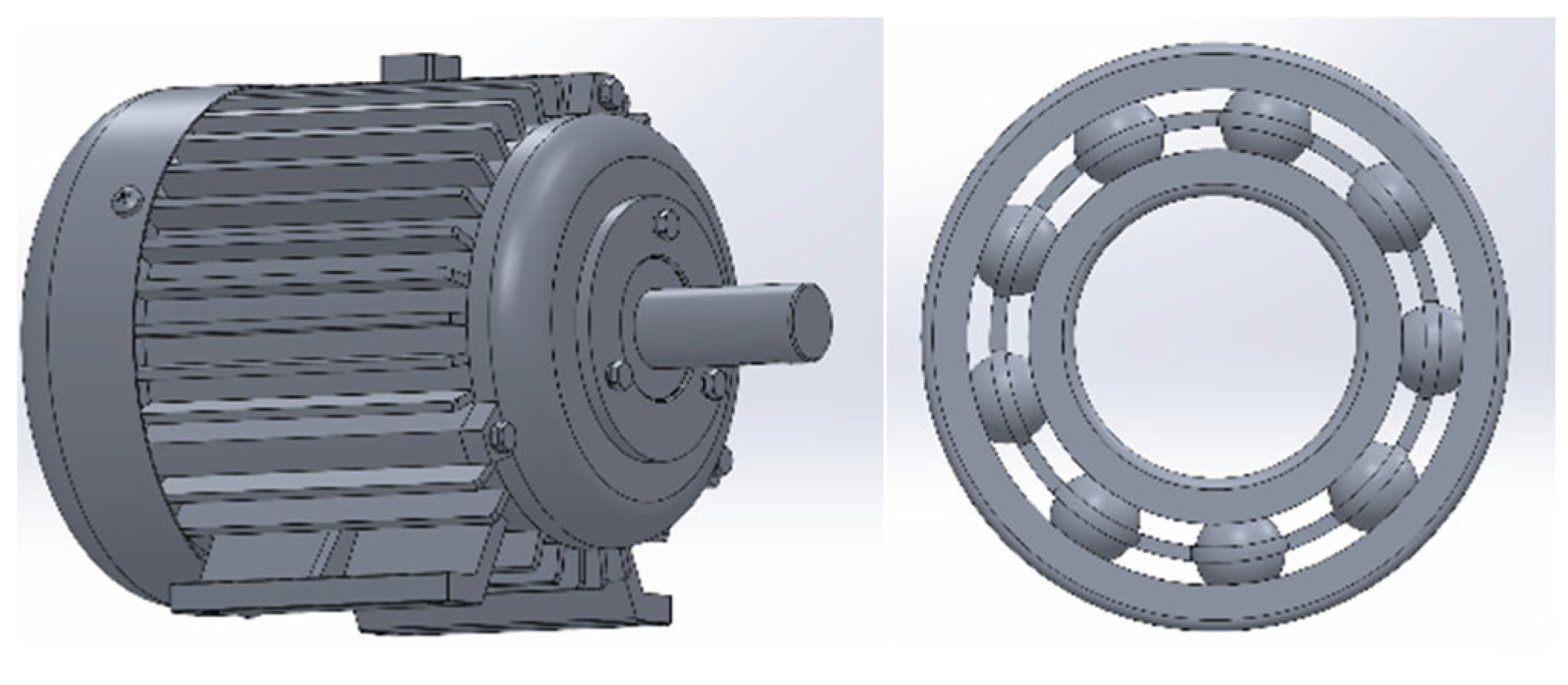

3.2.1. Geometric Model Construction

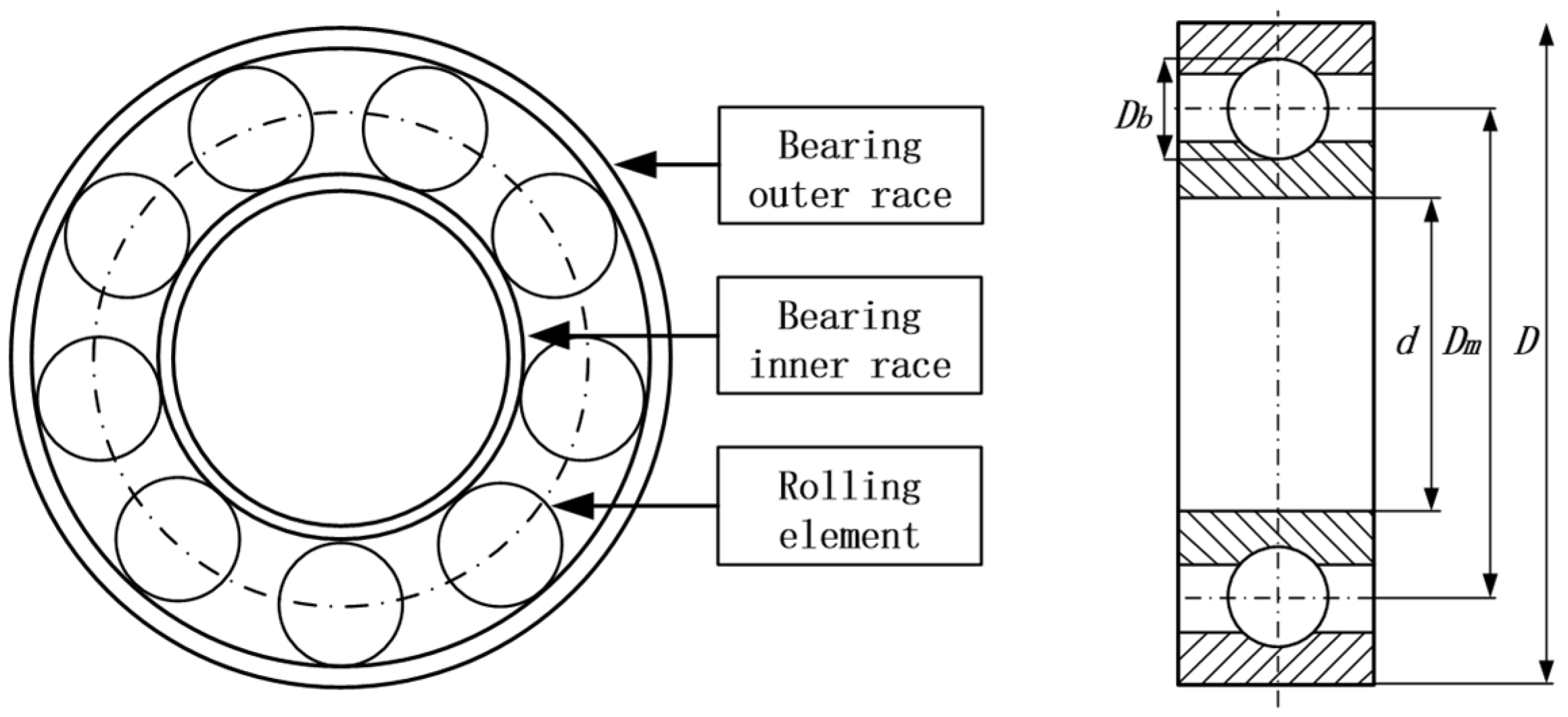

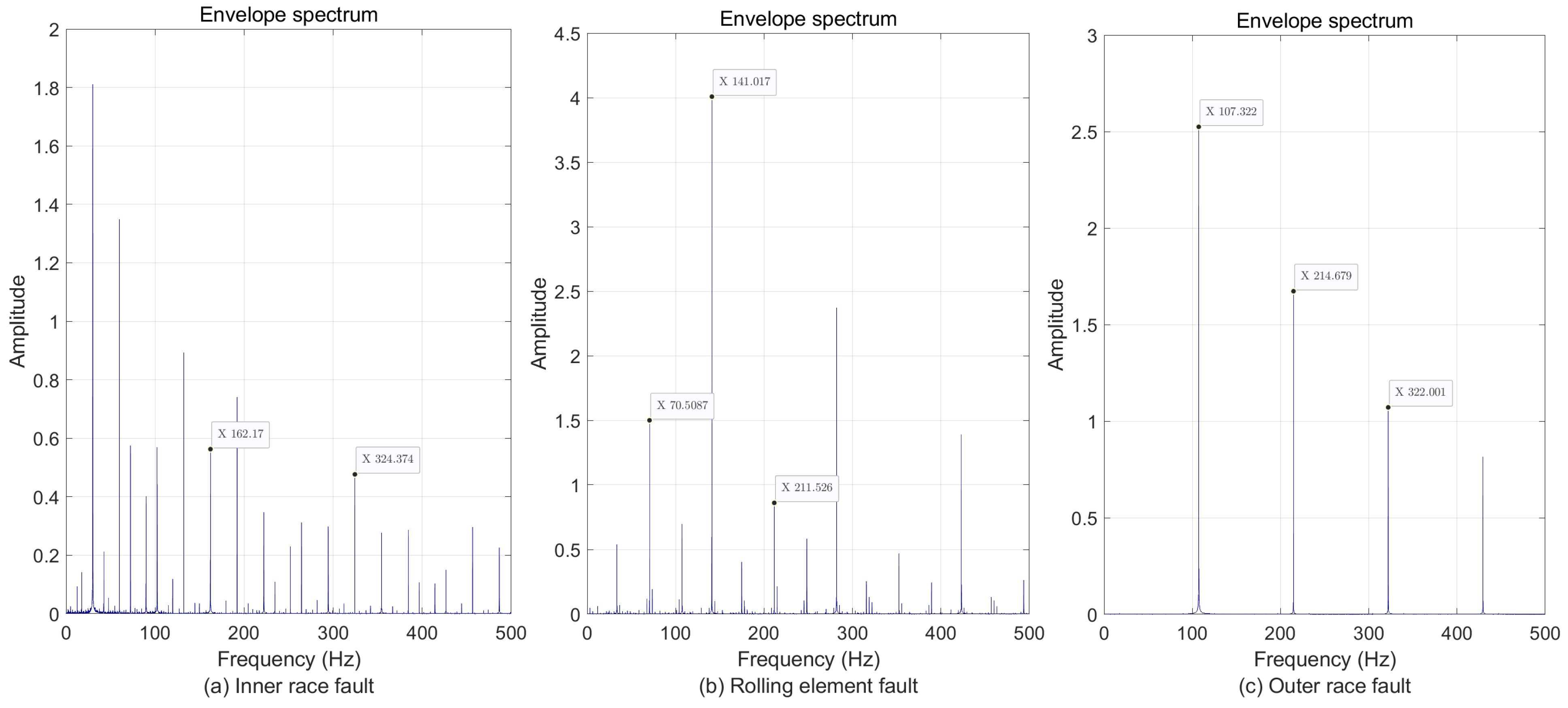

3.2.2. Analytical Model Construction

- (1)

- The calculation formula for the inner race fault characteristic frequency (BPFI):

- (2)

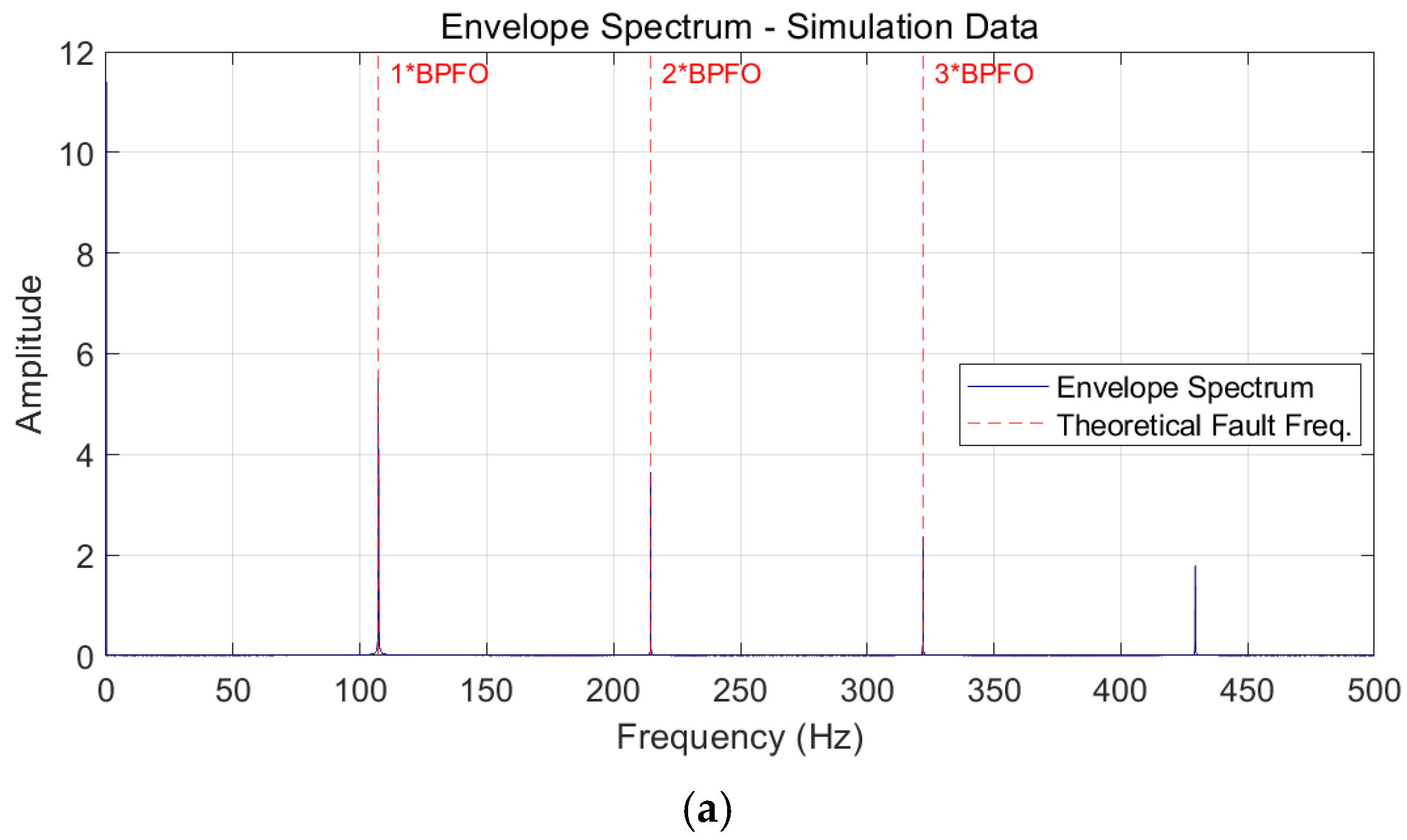

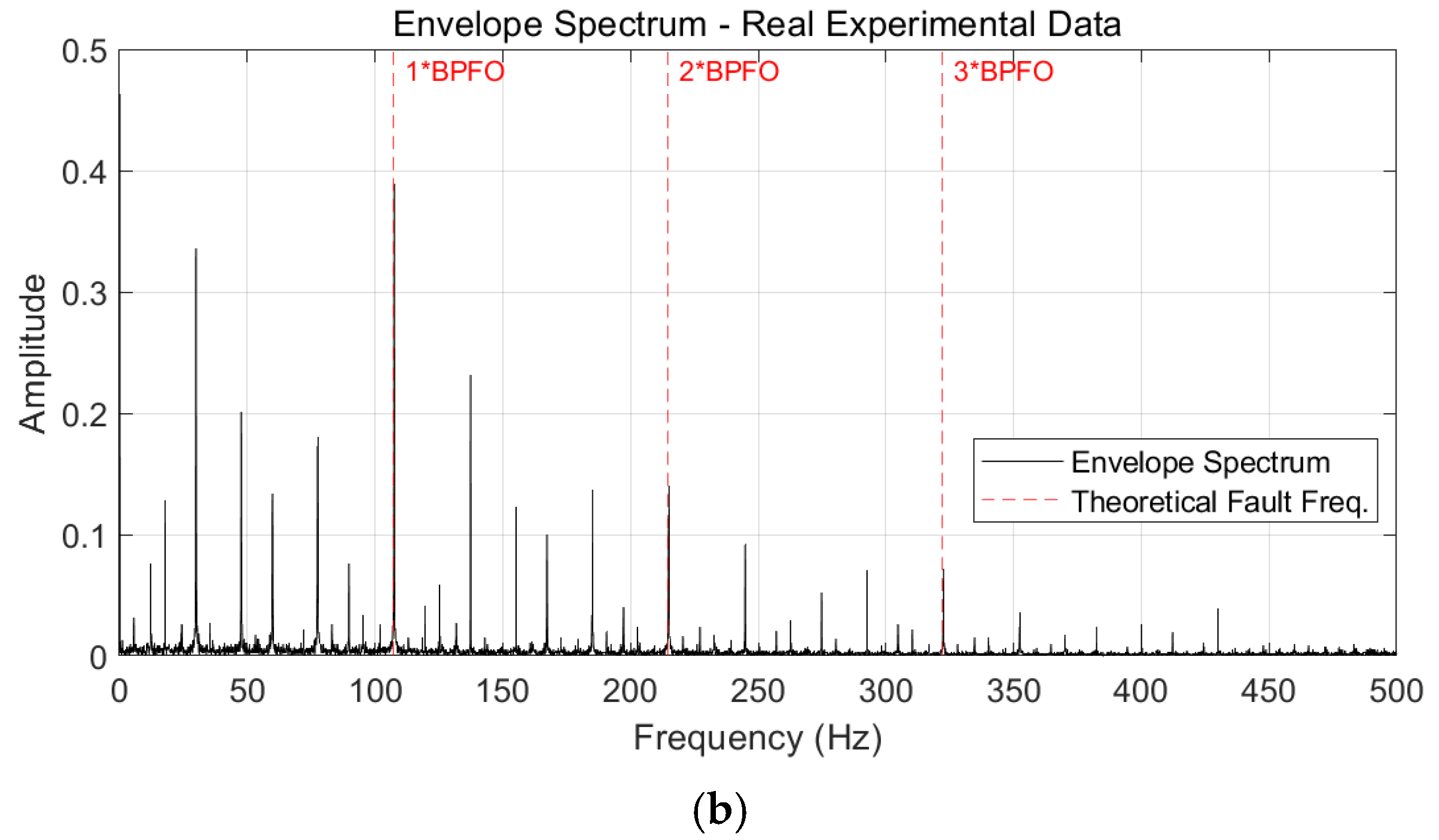

- The calculation formula for the outer race fault characteristic frequency (BPFO):

- (3)

- The calculation formula for the rolling element fault characteristic frequency (BSF):

3.3. Fault Diagnosis of Motor Bearings

| Algorithm 1: Subtraction-average-based optimizer (SABO) |

| Input: N: Population size T: Maximum number of iterations lo, hi: Lower and upper bounds of variables m: Dimension of the problem fitness(): The objective function data: Input signal for the fitness function Output: Best_pos: Best solution found (optimal k and α) Best_score: Fitness value of the best solution 1: Initialize population X of N agents randomly within bounds [lo, hi]. 2: Calculate initial fitness score_i for each agent X_i. 3: Find initial global best X_best and f_best. 4: For t = 1 to T do: 5: For each agent X_i do: 6: Initialize difference vector DX = [0, …, 0]. 7: For each agent X_j do: 8: I = round(1 + rand() + rand()) 9: For d = 1 to m do (for each dimension): 10: DX[d] = DX[d] + (X_j[d] − I * X_i[d]) * sign(score_i − score_j) 11: End For 12: End For 13: r = random vector of size m with elements in [0, 1] 14: X_new = X_i + (r .* DX) / N // . denotes element-wise multiplication 15: Apply bounds to X_new. 16: score_new = fitness(X_new, data) 17: If score_new < score_i then: 18: X_i = X_new 19: score_i = score_new 20: End If 21: End For 22: Update global best X_best and f_best. 23: End For 24: Return X_best as Best_pos and f_best as Best_score. |

4. Experiments and Analysis

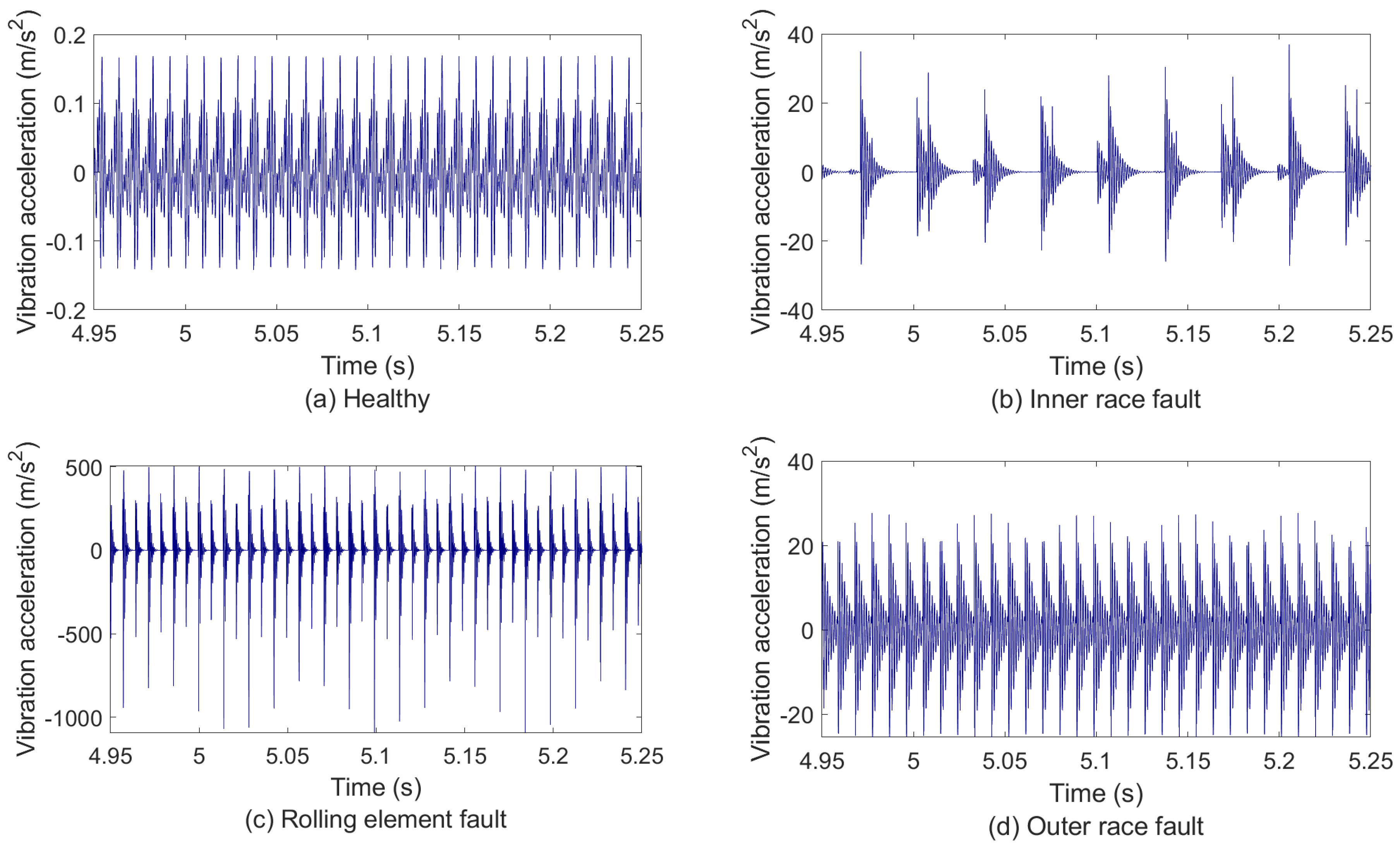

4.1. Experiment 1: Simulation Data

- (1)

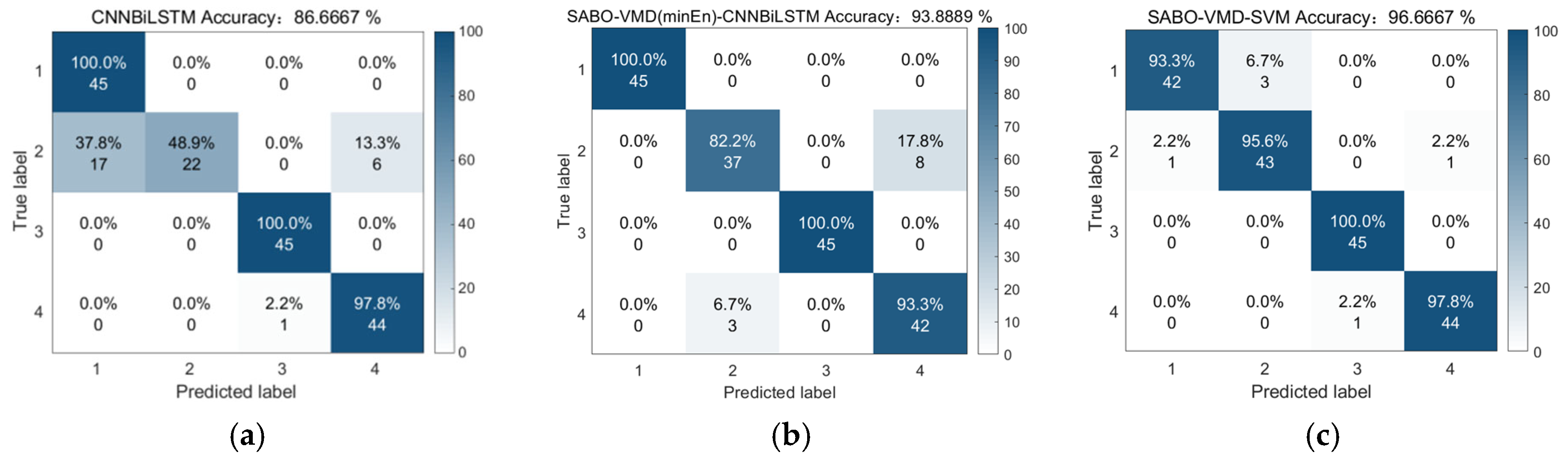

- CNN-BiLSTM method: This approach inputs raw vibration signals directly into a CNN-BiLSTM model without any preprocessing or parameter optimization.

- (2)

- SABO-VMD (minEn)-CNN-BiLSTM method: Here, the optimization algorithm’s fitness function is replaced with minimum envelope entropy (minEn) instead of the combined PE/MIE metric. The VMD parameters are optimized accordingly, and the resulting features are classified using the CNN-BiLSTM model.

- (3)

- SABO-VMD-SVM method: This method applies the subtraction-average-based optimizer (SABO) to optimize VMD parameters for feature extraction, followed by classification with a support vector machine (SVM) instead of CNN-BiLSTM.

- (1)

- The optimization performance differences under different fitness functions (e.g., combined PE/MIE vs. minimum envelope entropy);

- (2)

- The impact of parameter optimization (via SABO) on diagnostic accuracy;

- (3)

- The interaction between feature extraction techniques and classifiers, highlighting how their appropriate pairing can improve overall diagnostic performance.

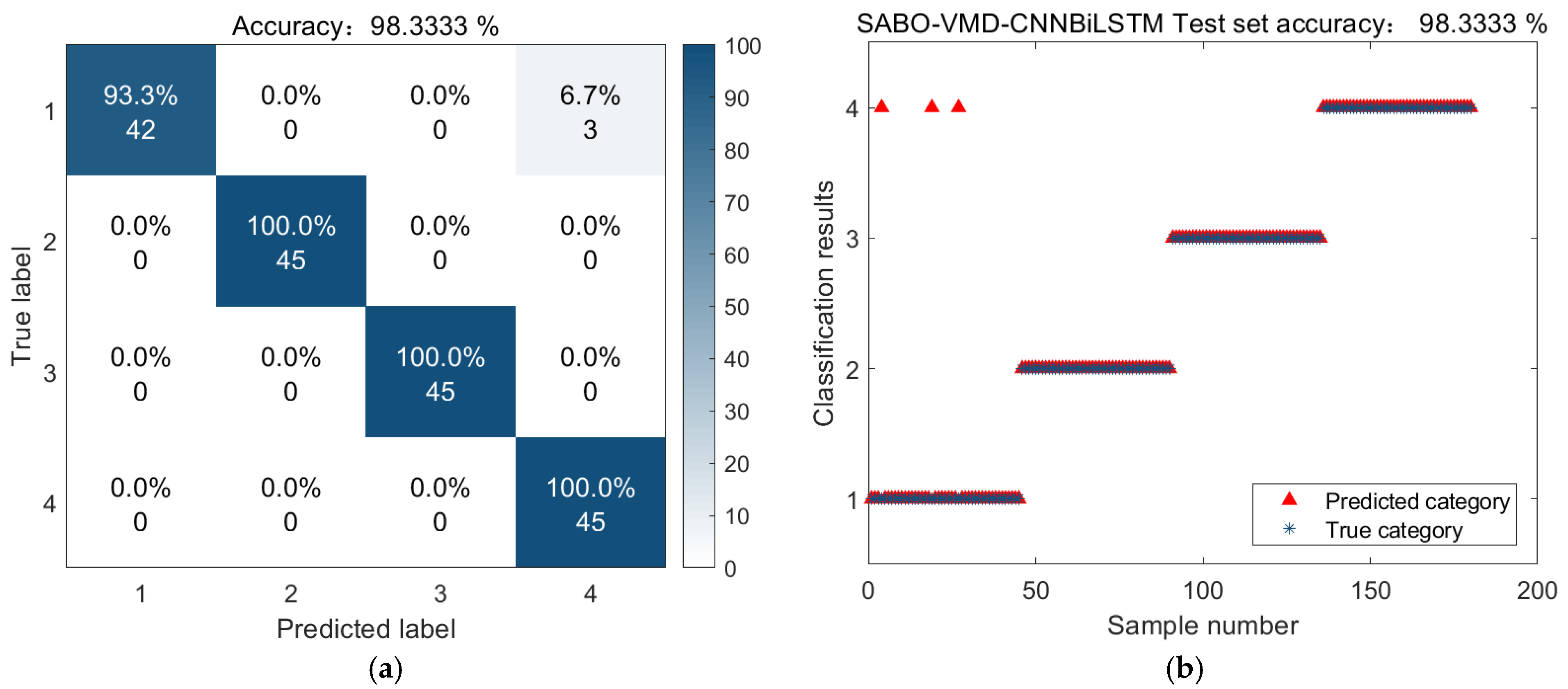

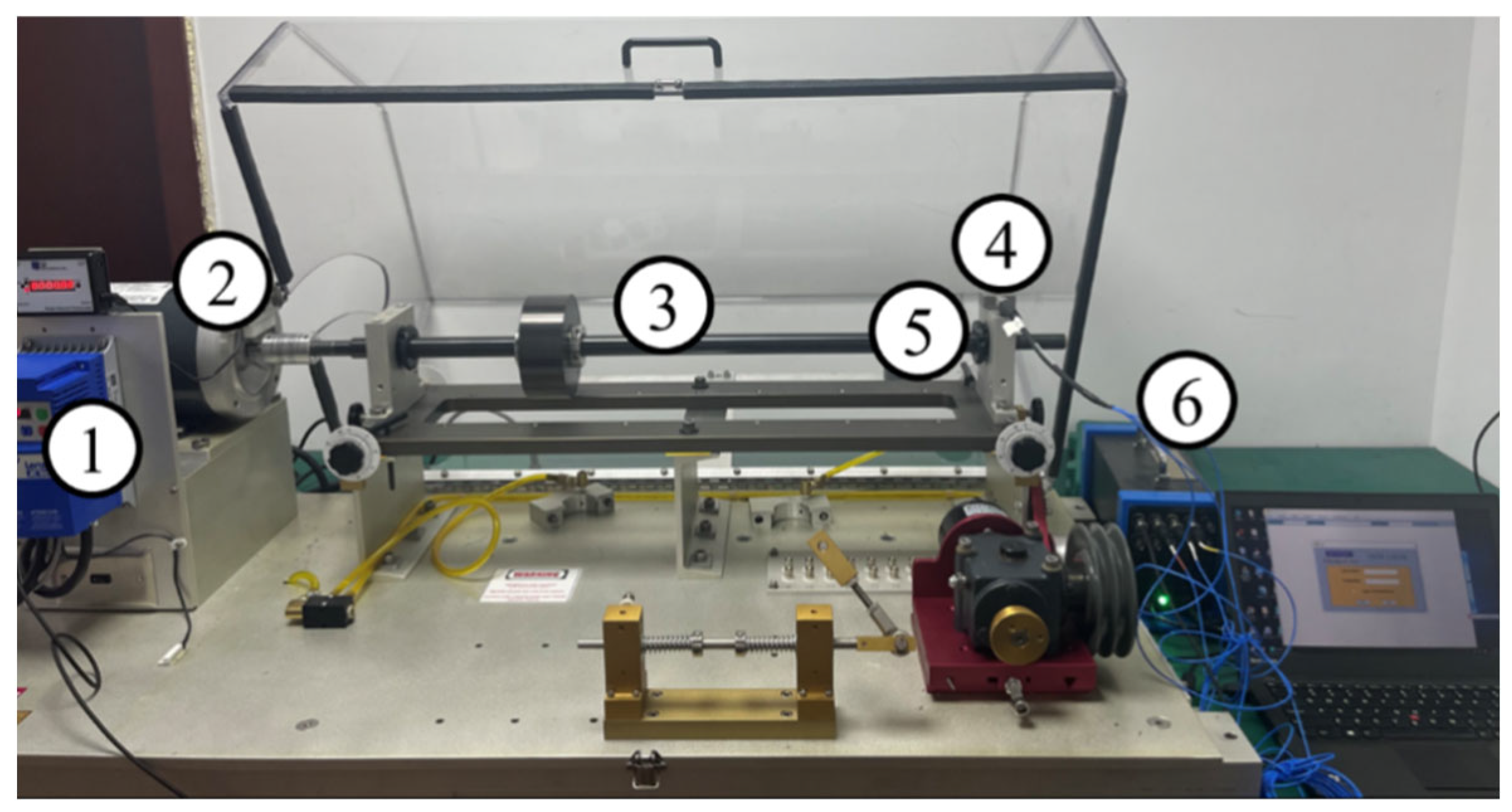

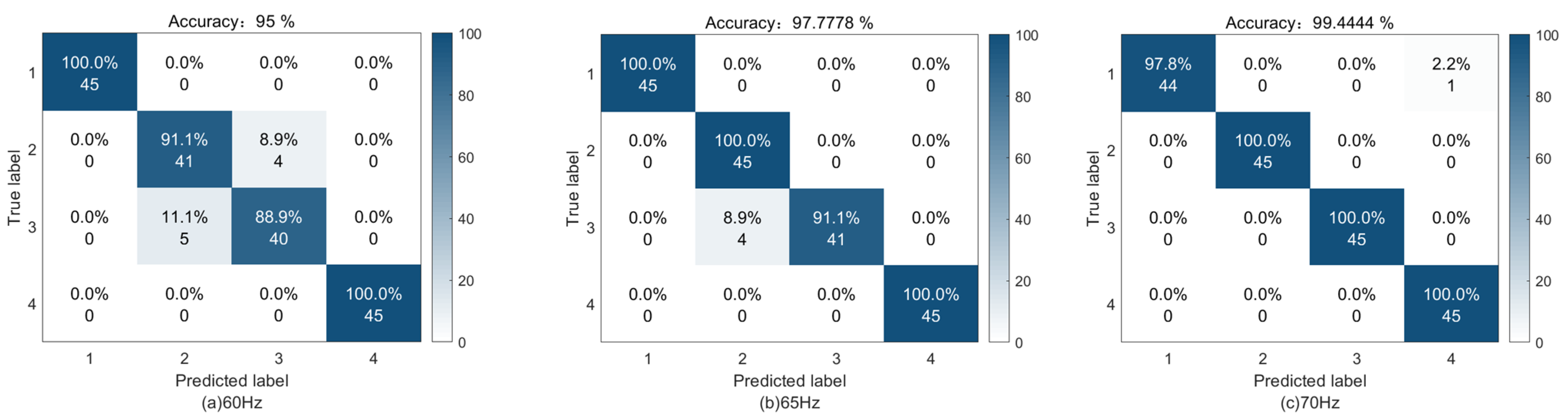

4.2. Experiment 2: HUST Bearing Dataset

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, X.; Fan, D.; Xiang, Z.; Quan, L.; Hua, W.; Cheng, M. Systematic multi-level optimization design and dynamic control of less-rare-earth hybrid permanent magnet motor for all-climatic electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q. Design of Active Disturbance Rejection Controller in Speed Loop for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Wind Power Generation System. Control Eng. 2022, 29, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. Digital Twins for Circular Economy Optimization: A Framework for Sustainable Engineering Systems. Proceedings 2025, 121, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Zha, W. Application of Intelligent Technology in Relay Protection Status Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis. Electron. Technol. 2024, 53, 190–191. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, S.; Vaimann, T.; Asad, B.; Kallaste, A.; Sardar, M.U.; Kudelina, K. State-of-the-Art Techniques for Fault Diagnosis in Electrical Machines: Advancements and Future Directions. Energies 2023, 16, 6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Jiang, X.; Fu, Q. Study on application of spectral analysis of instantaneous power to fault diagnosis of traction motor rotor. Electro Mach Control 2012, 16, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Zhang, J.; Xie, L. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Rolling Bearing Based on Gramian Angular Difference Field and Improved Dual Attention Residual Network. Sensors 2024, 24, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, S.; Su, K.; Yu, J.; Li, X.; Shen, H. An unsupervised transfer learning bearing fault diagnosis method based on multi-channel calibrated Trans-former with shiftable window. Struct. Health Monit. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsallis, C.; Papageorgas, P.; Piromalis, D.; Munteanu, R.A. Application-Wise Review of Machine Learning-Based Predictive Maintenance: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Motor Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on EEMD-IGWO-SVM. Mach Tool Hydraul. 2024, 52, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia, M.; Garcia-Alfaro, J. Design, Modeling and Implementation of Digital Twins. Sensors 2022, 22, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Srivastava, R.; Fuenmayor, E.; Kuts, V.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Applications of Digital Twin across Industries: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleich, B.; Anwer, N.; Mathieu, L.; Wartzack, S. Shaping the digital twin for design and production engineering. CIRP Ann.—Manuf. Technol. 2017, 66, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.; Schleich, B.; Haefner, B.; Kuhnle, A.; Wartzack, S.; Lanza, G. Challenges and Potentials of Digital Twins and Industry 4.0 in Product Design and Production for High Performance Products. Procedia CIRP 2019, 84, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, C.; Cardin, O.; Gallot, G.; Viaud, J. Designing the Digital Twins of Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems: Application on a smart factory. IFAC-Pap. 2021, 54, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Arunachalam, N. A digital twin for grinding wheel: An information sharing platform for sustainable grinding process. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2019, 141, 021015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Yazdanianasr, M.; Mauricio, A.; Verwimp, T.; Desmet, W.; Gryllias, K. Physics-driven cross domain digital twin framework for bearing fault diagnosis in non-stationary conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 228, 112266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xie, T.; Luo, S.; Wu, J.; Luo, R.; Zhou, Q. Incremental learning with multi-fidelity information fusion for digital twin-driven bearing fault diagnosis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Manickavasagam, K.; Tengenkai, N.; Vijayalakshmi, N. Health monitoring and prognosis of electric vehicle motor using intelligent-digital twin. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2019, 13, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshoombe, B.K.; Dos Santos, J.F.; Araújo, R.C.; Fonseca, W.D. Implementation of DT-based monitoring system of induction motors. In Proceedings of the 2021 14th IEEE International Conference on Industry Applications (INDUSCON), São Paulo, Brazil, 15–18 August 2021; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Q.; Tao, F.; Hu, T. Enabling technologies and tools for digital twin. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Huang, H.; Cao, L. Research on Intelligent Manufacturing Digital Twin Conceptual Model and Key Technologies. Inf. Technol. Stand. 2024, 11, 45–50+60. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Tang, L.; Chen, Q. Survey on digital twin network towards 6G: Architectures, applications and challenges. J. Chongqing Univ. Posts Telecommun. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 36, 633–646. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Qi, Q.; Xu, J. Theory of digital twin modeling and its applicatio. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wen, Z.; Jin, X. Calculation Method of Hertz Normal Contact Stiffness. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2021, 56, 883–890. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Wang, J.; Song, Q.; Li, K.; Hao, W.; Jiang, H. Fault diagnosis of HVCB via the subtraction average based optimizer algorithm optimized multi channel CNN-SABO-SVM network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, N. Application of WOA-VMD Algorithm in Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Noise Vib. Control 2021, 41, 86–93+275. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X. Research on equipment fault diagnosis and health management model based on BPneural network and genetic algorithm. Manuf. Technol. Mach. Tool 2024, 11, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Huo, Y.; Ni, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Fault diagnosis of floating offshore wind turbine based on bidirectional long short-term memory networks with sliding window. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2025, 239, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zio, E.; Shen, W. Domain generalization for cross-domain fault diagnosis: An application-oriented perspective and a benchmark study. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 245, 109964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Name | Title 2 Value |

|---|---|

| Outer race diameter D/mm | 52 |

| Inner race diameter d/mm | 25 |

| Rolling element diameter Db/mm | 7.94 |

| Bearing pitch diameter Dm/mm | 39 |

| Number of rolling elements Nb | 9 |

| Radial clearance Cr/mm | 5 × 10−3 |

| Outer race mass mo/kg | 12.64 |

| Inner race mass mi/kg | 5.5 |

| Outer race support damping co/(Ns/m) | 2310.68 |

| Inner race support damping ci/(Ns/m) | 3376.84 |

| Outer race support stiffness ko/(N/m) | 1.51 × 107 |

| Inner race support stiffness ki/(N/m) | 5.24 × 104 |

| Labels | k | α | Optimal IMF Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 2313 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 454 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 | 275 | 1 |

| 4 | 10 | 2291 | 2 |

| Class (Label) | Fault Type | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal | 1.000 | 0.933 | 0.965 |

| 2 | Inner race fault | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 3 | Rolling element fault | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 4 | Outer race fault | 0.938 | 1.000 | 0.968 |

| Fault-Diagnosis Method | Fitness Function | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| SABO-VMD-CNN-BiLSTM | PE-MIE | 98.33% |

| CNN-BiLSTM | —— | 86.67% |

| SABO-VMD (minEn)-CNN-BiLSTM | minEn | 93.89% |

| SABO-VMD-SVM | PE-MIE | 96.67% |

| Fault Type | Sample Count | Label |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 150 | 1 |

| Inner race fault | 150 | 2 |

| Rolling element fault | 150 | 3 |

| Outer race fault | 150 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y. Research on Fault-Diagnosis Technology of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motor Based on Digital Twin. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091494

Ma Y, Zhu Y. Research on Fault-Diagnosis Technology of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motor Based on Digital Twin. Symmetry. 2025; 17(9):1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091494

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yangrui, and Yaqiao Zhu. 2025. "Research on Fault-Diagnosis Technology of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motor Based on Digital Twin" Symmetry 17, no. 9: 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091494

APA StyleMa, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Research on Fault-Diagnosis Technology of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motor Based on Digital Twin. Symmetry, 17(9), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17091494