Abstract

An involutive m-semilattice is a kind of algebraic structure with symmetry. Symmetry is reflected from partial-order relations to algebraic operations and even categorical properties. In this study, firstly, the concepts of the nucleus and congruence in involutive m-semilattices are introduced, and their interrelationships are discussed. On this basis, the concrete structure of a coequalizer in the category of involutive m-semilattices is obtained. We introduce the definition of free involutive m-semilattices, and the concrete structure of involutive m-semilattices is discussed. In addition, It is shown that the category of involutive m-semilattices is algebraic. Secondly, the colimit in the category of involutive m-semilattices is shown to be a very difficult problem. We obtain the concrete structure of the colimit for a full subcategory of the category of involutive m-semilattices. Thirdly, we introduce the definition of an inverse system in the category of involutive m-semilattices and give the concrete structure of the inverse limit of an inverse system. We establish the concept of a mapping between two inverse systems. The properties of inverse limits are discussed. Finally, we study the direct limit of the category of involutive m-semilattices and give its concrete structure.

MSC:

06B10; 18A30; 18B35

1. Introduction

The quantale was proposed by Mulvey in 1986 in [1] as a combination of quantum logic and locale. The algebraic structure of a quantale inherently exhibits symmetry. For instance, the distributive property of multiplication over a supremum operation embodies a form of symmetric relation. Additionally, symmetry is reflected in the characteristics of multiplication operations under arbitrary permutations of elements. Quantale theory provides a powerful tool for studying non-commutative structures and a new mathematical model for quantum mechanics. Hence, the theory of quantales has attracted the attention of many scholars. Quantale theory has a wide range of applications, especially when studying non-commutative structures [2], linear logic [3,4,5], C*-algebras [6], topological space [7,8,9], category [10,11,12], roughness theory [13], and so on. A systematic introduction to quantale theory written by Rosenthal in 1990 can be found in [14].

m-semilattices are important structures that are related to quantales. Rosenthal proved that each coherent quantale is isomorphic to a quantale consisting of all ∨-semilattice ideals of an m-semilattice with a top element. A coherent quantale is a special type of quantale characterized by properties such as symmetry, right-sidedness, and semiprimeness. These characteristics confer upon it a significant role in the study of mathematical logic and algebraic structures. Since m-semilattices connect the structures of ∨-semilattices with multiplications of semigroups, m-semilattices can be regarded as generalizations of residual lattices, lattice-ordered semigroups, quantales, and frames. m-semilattice theory has aroused great interest from many scholars. In [15], by using the fuzzy set method, the concept of (prime) ideals of an m-semilattice was introduced. Equivalent characterizations of (prime) ideals and (prime) ideas were given. In [16], Zhou and Zhao proposed the congruences induced by the fuzzy (prime) ideals of an m-semilattice, studied the properties of the upper (lower) rough fuzzy approximation operators with respect to these congruences, and introduced the notion of rough fuzzy (prime) ideals of m-semilattices. In [17], a minimal neighborhood approximation operator on m-semilattices was studied, and the definition of fuzzy rough sets based on fuzzy coverings of m-semilattices was introduced. In [18], Su and Zhao introduced the concept of filters in m-semilattices, and a filter topology on m-semilattices was constructed. A series of properties of filter spaces was studied. In [19], Pan and Han proved that the category of coherent quantales is a reflective subcategory of the category of m-semilattices. Based on the definition of m-semilattices, the concept of involutive m-semilattices was given. A series of important properties of involutive m-semilattices were studied, and it was proven that the category of involutive m-semilattices is complete ([20]). In [21], the definition of the generalized M-P inverse of an m-semilattice matrix was introduced. The necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a generalized M-P inverse of an m-semilattice matrix was obtained. Some scholars have also provided different definitions of m-semilattices against various research backgrounds [22,23,24,25].

The category theory provides a new language that affords economy of thought and expression, in addition to allowing easier communication among investigators in different areas. The symmetry within a semilattice is manifested through its operational rules and partial-order relations, representing a form of mathematical abstract symmetry. Symmetry is a highly abstract mathematical concept in category theory, and it is manifested through the properties of morphisms and the structure of categories. For example, natural equivalences, symmetric categories, the commutativity of morphisms, and duality are all manifestations of symmetry. This symmetry not only reveals the deep connections between different areas of mathematics but also plays a significant role in fields such as physics. Understanding symmetry in category theory helps us gain a deeper insight into the nature of mathematical and physical phenomena.

In the literature on the study of m-semilattices, the focus has primarily been on ideals, filters, topological properties, roughness, fuzzy roughness, and matrices, with little discussion on categorical properties. We have added a unary involution operation to the m-semilattice, similar to the negation operator in algebraic logic, making the involution m-semilattice an extension of the m-semilattice. This article investigates the properties of involutive m-semilattices from a categorical perspective. The algebraic properties and limit structures of a category are important research focuses. If the algebraic properties of a category are proven and its limit structures are provided, then many categorical properties naturally hold. This study researches the algebraic properties of the category of involutive m-semilattices, as well as the structures of its colimits, direct limits, and inverse limits. In the following, some simple concepts of category theory are taken from [26].

This article is organized as follows. In Section 1, we show some basic concepts and the results needed in this article. In Section 2, the concepts of the nucleus and congruence are introduced. The category of involutive m-semilattices is proven to be algebraic. In Section 3, we discuss the structure of the coproduct and colimit in the category of involutive m-semilattices. In Section 4, we study the inverse limit and direct limit in the category of involutive m-semilattices. The properties of inverse limits are discussed.

For the convenience of readers, the important symbols used in this article can be found in the table below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Symbol description.

2. Preliminaries

Definition 1.

Let be a ∨-semilattice, let be a semigroup, and let ∗ be a unary operation on S satisfying the following:

- (1)

- for all .

- (2)

- for all .

- (3)

- for all .

- (4)

- for all .

Then, is called an involutive m-semilattice.

The definition of the involutive m-semilattice given in this paper is an extension of the definition of the involutive m-semilattice introduced in reference [20].

Definition 2.

Let and be two involutive m-semilattices. A mapping is said to be an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism if it satisfies the following:

- (1)

- ;

- (2)

- ;

- (3)

- .

Example 1.

(1) Let be a Boolean algebra. We define a semigroup multiplication · on B and an involution operation ∗ on B as follows:

It can be verified that is an involutive m-semilattice, and it is commutative. Let B be a two-element Boolean algebra. We define a mapping as follows: , then the mapping f is both a Boolean algebra homomorphism and an involution m-semilattice homomorphism.

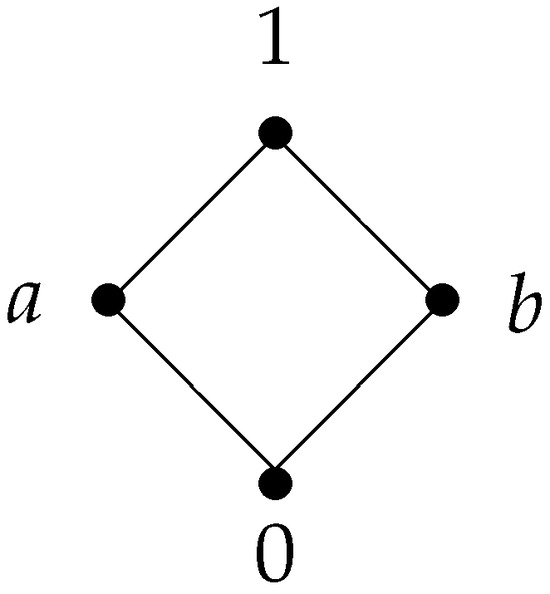

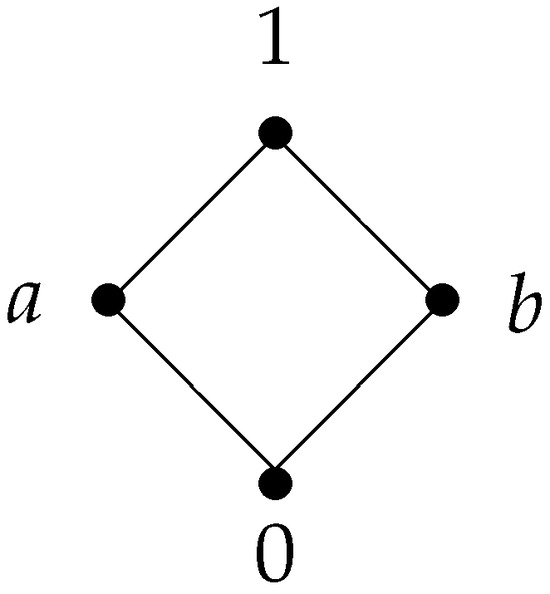

(2) Let be a lattice determined by Figure 1. A semigroup multiplication on S and an involution operation on S are determined by the tables below (Table 2 and Table 3).

Figure 1.

The partial order on S.

Table 2.

The semigroup multiplication on S.

Table 3.

The involution operation on S.

It can be verified that is an involutive m-semilattice, and it is symmetric and commutative. By the definitions of m-semilattice ideals and filters, the sets , , , and are ideals of S, while , , , and are filters of S.

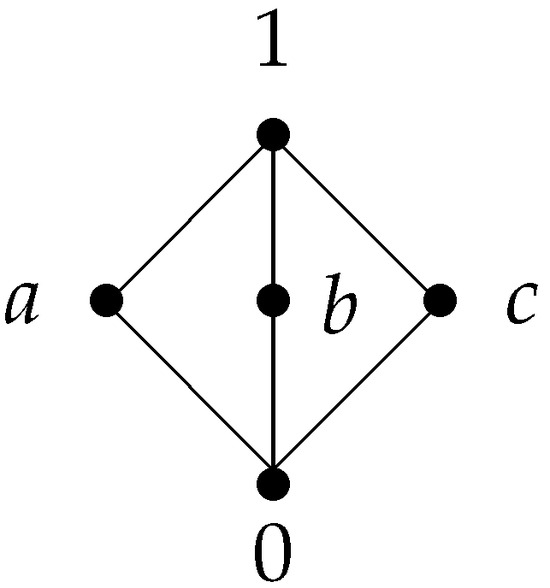

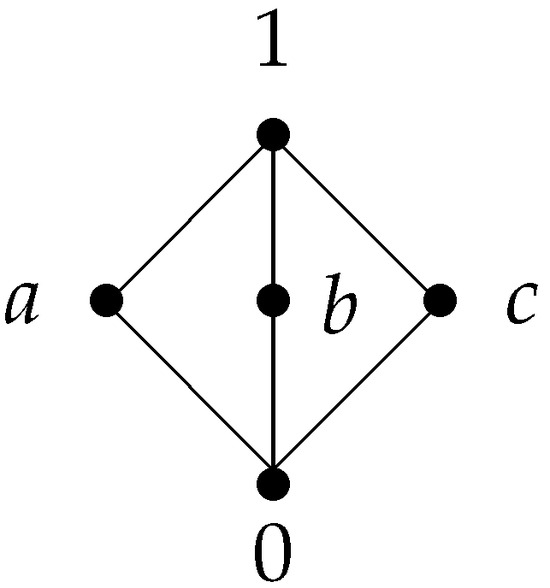

(3) Let be a lattice determined by Figure 2. A semigroup multiplication on S and an involution operation on S are determined by the tables below (Table 4 and Table 5).

Figure 2.

The partial order on S.

Table 4.

The semigroup multiplication on S.

Table 5.

The involution operation on S.

It can be verified that is an involutive m-semilattice, and it is symmetric and commutative. By the definitions of m-semilattice ideals and filters, the sets , , , , and are ideals of S, while , , , and are filters of S.

Definition 3 ([26]).

A category is a quintuple , where

(1) is a class whose members are called -objects;

(2) is a class whose members are called -morphisms;

(3) and are functions from to ; () is called the domain of f, and is called the codomain of f;

(4) ∘ is a function from to , and this is called the composition law of , which is usually written as . We say that is defined if, and only if, c such that the following conditions are satisfied:

(i) Matching Condition: If is defined, then and ;

(ii) Associativity Condition: If and are defined, then ;

(iii) Identity Existence Condition: For each -object A, there exists a -morphism e such that and

- (a)

- whenever is defined;

- (b)

- whenever is defined.

(iv) Smallness of Morphism Class Condition: For any pair of -objects, the class

is a set.

For a given category , the class of -objects will be denoted by , whereas will stand for the class of -morphisms.

Example 2 ([26]).

In the category Set, the class of objects is the class of all sets, the morphisms sets are all functions from A to B, and the composition law is the usual composition of functions. Set is commonly called the category of sets.

Definition 4 ([26]).

A category is said to be the following:

(1) small provided that is a set;

(2) discrete provided that all of its morphisms are identities;

(3) connected provided that for each pair of -objects, .

Definition 5 ([26]).

Let and be categories, A functor from to is a triple , which is a function from the class of morphisms with respect to the class of morphisms of (i.e., satisfying the following conditions:

(1) F preserves identities, i.e., if e is a -identity, then is a -identity.

(2) F preserves composition; , i.e., whenever , then , and the above equality holds.

For any concrete category , there is a functor that assigns to any object A the underlying set and to any morphism the corresponding function on the underlying sets. U is called a forgetful functor on .

Definition 6 ([26]).

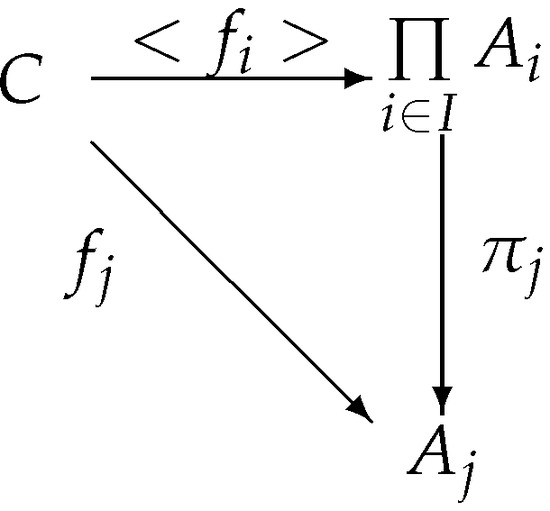

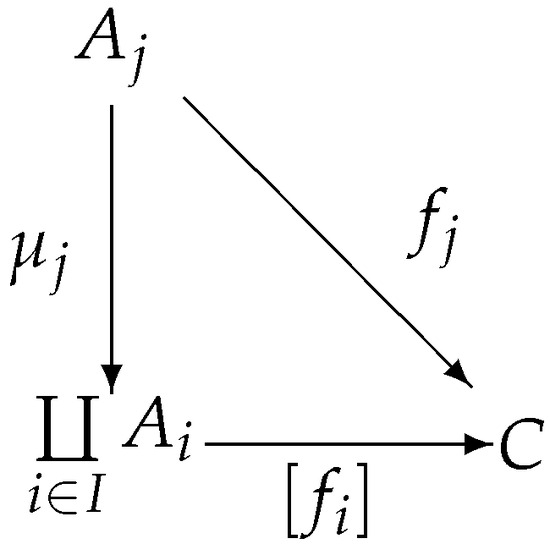

A product of a family of -objects is a pair satisfying the following properties:

(1) is a -object.

(2) For each , is a -morphism (called the projection from to ).

(3) For each pair , where C is a -object and for each , , there exists a unique -morphism such that, for each , Figure 3 commutes.

Figure 3.

Product diagram.

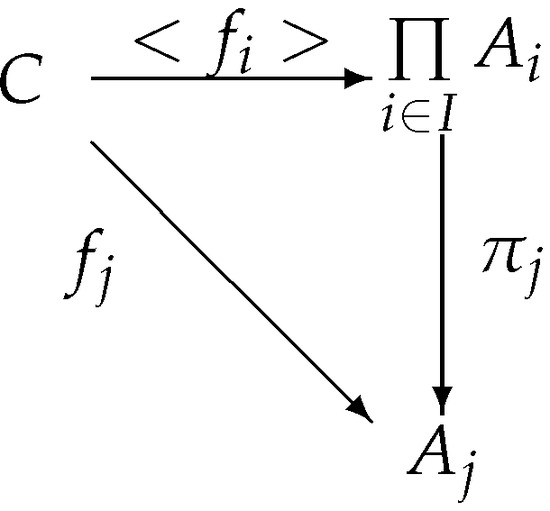

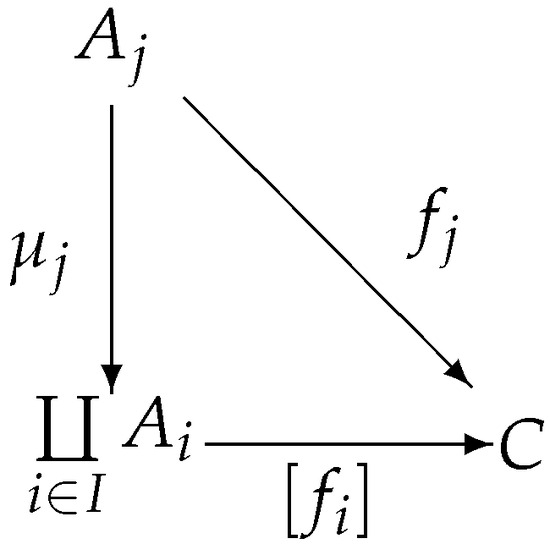

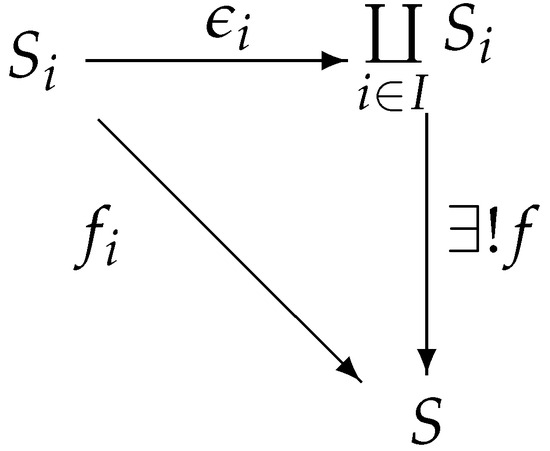

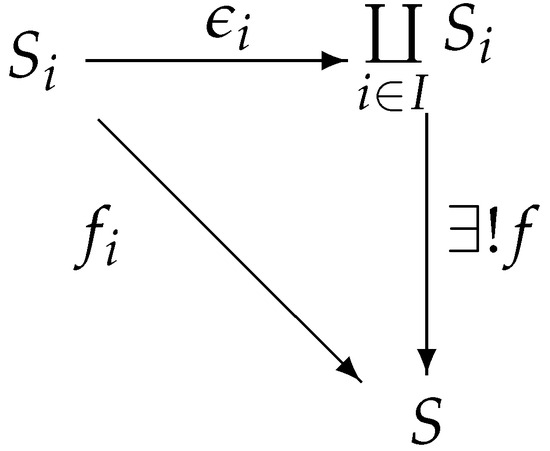

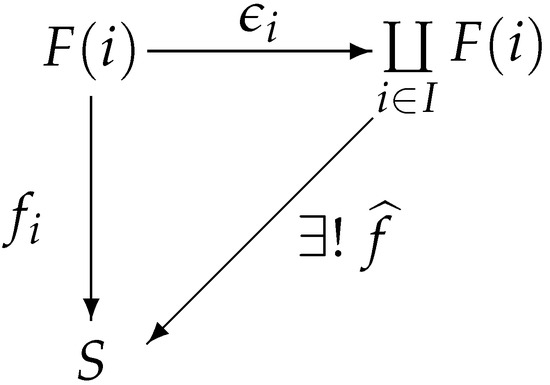

Definition 7 ([26]).

A coproduct of a family of -objects is a pair satisfying the following properties:

(1) is a -object.

(2) For each , is a -morphism (which is called the injection from to ).

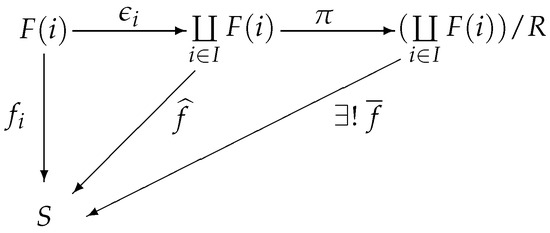

(3) For each pair , where C is a -object and for each , , there exists a unique -morphism such that for each , Figure 4 commutes.

Figure 4.

Coproduct diagram.

Definition 8 ([26]).

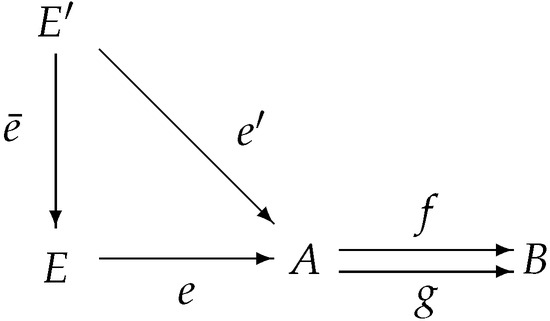

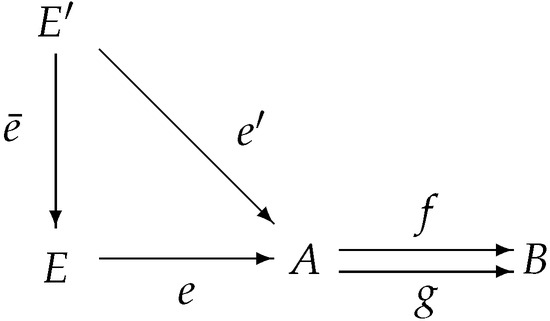

Let be a pair of -morphisms. A pair is called an equalizer in of f and g provided that the following hold:

(1) is a -morphism;

(2) ;

(3) For any -morphism such that , there exists a unique -morphism such that Figure 5 commutes.

Figure 5.

Equalizer diagram.

Dually, if , then is called a coequalizer in for a pair if, and only if, and each morphism with the property that can be uniquely factored through c.

Definition 9 ([26]).

A category is called algebraic provided that it satisfies the following conditions:

(1) The category has coequalizers;

(2) The forgetful functor has a left adjoint;

(3) The forgetful functor preserves and reflects regular epimorphisms.

3. The Category of Involutive m-Semilattices Is Algebraic

In algebraic structure research, nucleus and congruences stand out as two key areas of focus. Both concepts are instrumental in constructing quotient structures, which, in turn, facilitates a deeper exploration of their important properties. Furthermore, nucleus and congruences often exhibit a mutually determining relationship. Showing a category is algebraic involves proving the existence of coequalizers, with congruences being the basis for their construction. Next, we will introduce nucleus mappings and congruences in involutive m-semilattices. “A category is algebraic” means that it possesses good properties similar to those of classical algebraic structures (such as groups, rings, modules, etc.) and their homomorphisms. It provides an abstract and unified perspective for understanding and connecting various algebraic theories. In [27]. Liu and Zhao proved that the category of quantales is algebraic. Next, we will discuss the algebraicity of the involutive m-semilattice category.

Definition 10.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice. A closure (coclosure) operator is an order-preserving increasing (decreasing), idempotent map . If j is a closure (coclosure) operator on S, then if, and only if, for all .

Definition 11.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice. An involutive m-semilattice nucleus on S is a closure operator j such that and for all . Let denote the set of all involutive m-semilattice nuclei on S.

Lemma 1.

Let j be an involutive m-semilattice nucleus on S; then, for all .

Definition 12.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice with a maximum element 1, .

(1) j is right-sided (left-sided) if, and only if, for all .

(2) j is commutative if, and only if, for all .

(3) j is idempotent if, and only if, for all .

(4) Let be the set of all fixed points of j; then, is called a quotient of S.

, . It can be verified that the three operations mentioned above are well defined.

Theorem 1.

Let S be an involutive m-semilatticewith a maximum element 1, ; then,

(1) j is right-sided (left-sided) if, and only if, is right-sided (left-sided).

(2) j is commutative if, and only if, is commutative.

(3) j is idempotent if, and only if, is idempotent.

Proof.

(1) Assume j is right-sided, then, , , i.e., . Hence, is right-sided.

Conversely, when is right-sided, it follows that for all . Then, . Since j is increasing, therefore , i.e., . Hence, j is right-sided.

Similarly, the case on the left can be proven.

(2) Assume j is commutative, then, , . Thus, . Therefore, is commutative.

Conversely, when is commutative. By Lemma 1, it follows that , . Thus, . Therefore, j is commutative.

(3) Let j be idempotent. then, , . Thus, is idempotent.

Conversely, Assume is commutative. By Lemma 1, it follows that , . This shows that j is idempotent. □

Definition 13.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice; the relation satisfies the following:

(1) implies for all ;

(2) implies for all ;

(3) If , then .

Then, R is called an involutive m-semilattice congruence on S.

For any , let denote the congruence class of x, and let denote the set of all congruences on S. Then, is a complete lattice with respect to the inclusion order.

Theorem 2.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice, and let j be a nucleus on S. Then, is an involutive m-semilattice, and is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism, where , .

Proof.

It can be verified that is a joint semilattice with a maximum element.

We will show that is an involutive m-semilattice. For any , by the definition of and Lemma 1, we have . Thus, the associativity of is valid.

Next, we will show that the distributive law is valid. For any ,

(1) .

(2) By Lemma 1, we have .

Hence, . Similarly, it can be proven that the right-distributive law holds.

Finally, we will prove that is an involutive operation on .

For any ,

(1) .

(2) . By Lemma 1, it follows that . Thus .

(3)

Therefore, is an involutive operation on .

For any ,

(1) . By the definition of j, it follows that . Thus, .

(2) From Lemma 1, it follows that . Thus, j preserves operation .

(3) , but ; thus, .

From (1), (2), and (3), we know that mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism. □

Theorem 3.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice. , an equivalence R is defined as follows: if, and only if, for all . Then, R is a congruence on S.

Theorem 4.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice, and let R be a congruence of S. For all , define ; ; ; . The mapping such that . Then, is an involutive m-semilattice, and the mapping π is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

Proof.

We first show that ≤ is a partial order on .

For any ,

(1) It is clear that .

(2) If and , then and ; thus, .

(3) If and , then , i.e., .

It is easy to verify that the above operations and ∗ are well defined, and is a semilattice with a maximum element .

Next, for any , we have

(1) .

(2) . Similarly, it can be proven that also holds.

(3) We verify that ∗ is an involution operation on .

(i) .

(ii) .

(iii)

Therefore, is an involutive m-semilattice.

Finally, we will prove that the mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

For any ,

(1) .

(2) .

(3) . □

Definition 14.

Let be a category whose objects are involutive m-semilattices and whose morphisms are involutive m-semilattice homomorphisms. Obviously, the category is a concrete category.

Lemma 2.

Let be an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism; then, is an involutive m-semilattice congruence on S.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice, and let R be a binary relation on S. The smallest congruence containing R is the intersection of all the involutive m-semilattice congruences containing R on S. We say that this congruence is generated by R and is denoted by .

Theorem 5.

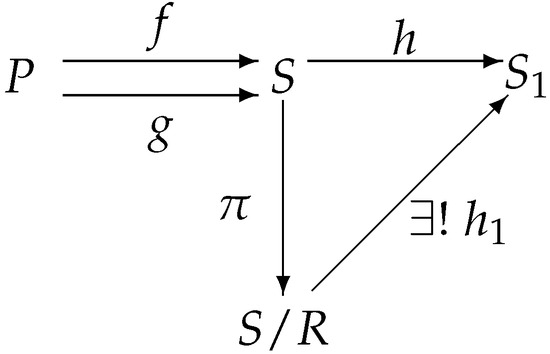

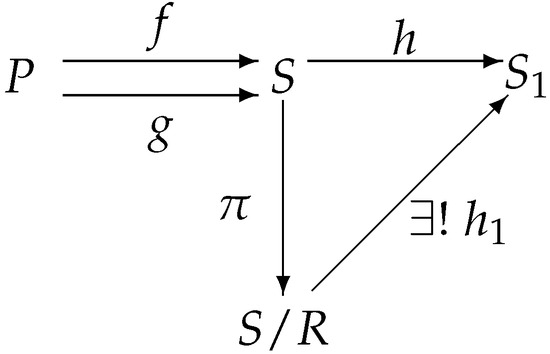

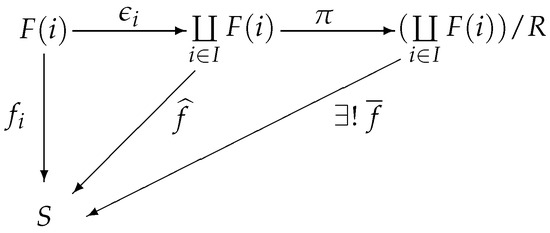

has a coequalizer.

Proof.

Let S and P be two involutive m-semilattices, let be two involutive m-semilattice homomorphisms, and let R be the smallest congruence, which contains .

Suppose that is the canonical mapping. Then, the mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism according to Theorem 4. We will show that is the coequalizer of f and g.

(1) Let ; then, and . Since , this implies that , i.e., .

(2) Let be an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism such that . Let and . According to Lemma 2, it follows that is a congruence of S. , then . This implies that ; thus, .

We define a mapping such that for all . Let ; then, , i.e., . This means that is well defined.

Let ; then,

(1) .

(2) .

(3) .

Hence, the mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

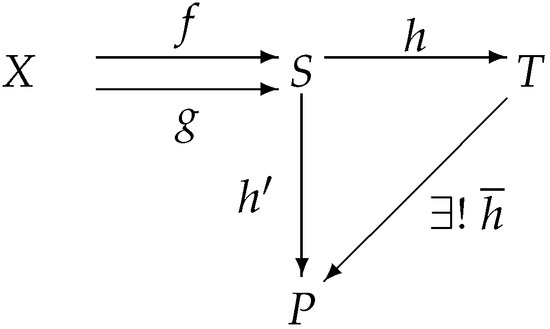

Let ; then, , i.e., . Thus, Figure 6 commutes.

Figure 6.

Coequalizer diagram.

Let such that ; then, , i.e., . Therefore, is the coequalizer of f and g. □

The problem of free generation plays a crucial role in algebra, and the free generation of some mathematical structures has been widely studied ([28,29]). Next, we will discuss the structure of free involutive m-semilattices in detail.

Let X be a set; we use to denote the set of all finite strings composed of elements from X. A binary operation ★ is defined as follows:

It is easy to verify that the binary operation ★ satisfies the associative law. is called the free semigroup generated by the set X.

Let denote the set of all finite subsets of the set . Two binary operations are defined on the set as follows:

Theorem 6.

The triple is an involutive m-semilattice with respect to the set inclusion order.

Proof.

We first show that the above operations and ∗ are well defined, and is a semilattice. For any . Since A and B are finite sets, suppose the cardinalities of A and B are and , respectively, i.e., , . We have

(1) . Hence, . Therefore, .

(2) . Hence, , Therefore, is a semilattice.

(3) . Then, .

Next, For any ,

(1)

Similarly, it follows that .

(2)

(3)

(4)

From the above proof, it can be seen that is an involutive m-semilattice. □

Theorem 7.

There is a functor that is left adjoint to the forgetful functor .

Proof.

Let X and Y be nonempty sets, and let be a mapping. According to Theorem 6, it follows that and are involutive m-semilattices. We define such that for all ; then, the mapping is well defined.

Next, we will prove that the mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism. For any ,

(1)

Therefore, the mapping f preserves the union of sets.

(2)

Therefore, the mapping preserves the operation •.

(3)

Hence, the mapping preserves the involutive operation ∗.

From the above proof, it can be concluded that the mapping is an involutive semilattice homomorphism.

Next, we will check that is a functor.

We define a mapping such that for all . For any ,

(1)

This means that the functor preserves identity mappings.

(2) Let , ; then,

Thus, the functor preserves the composition of f and g.

Finally, we will prove that is the left adjoint to the forgetful functor .

Let X be a non-empty set; we define a mapping such that for all . Let S be an involutive semilattice and mapping ; we define a mapping such that for all . Since is a finite set, then . This shows that the mapping is well defined.

For any ,

(1)

(2)

(3)

Hence, the mapping is an involutive semilattice homomorphism.

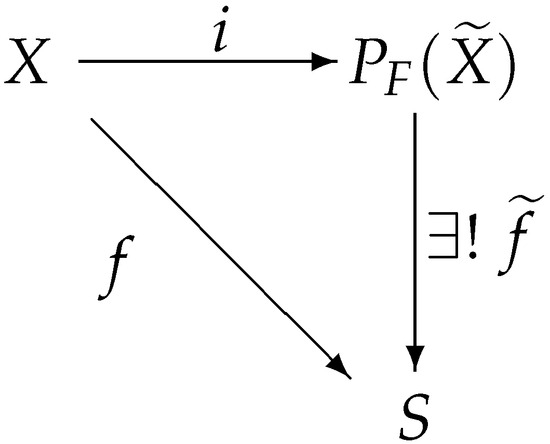

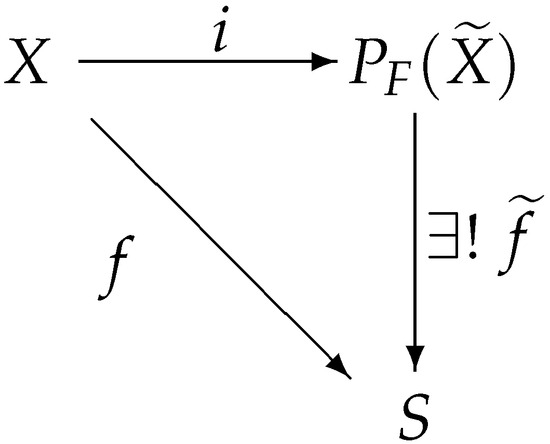

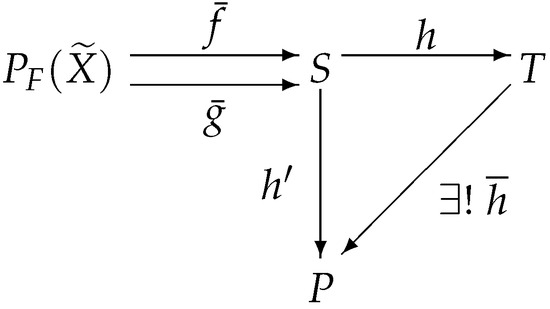

For any , , i.e., ; hence, Figure 7 commutes.

Figure 7.

Universal property diagram.

Suppose that is another homomorphism such that .

Then, , i.e., .

For any ,

Thus, . This means that is a unique involutive m-semilattice homomorphism and satisfies the commutativity of Figure 7.

The above proof shows that the functor is left adjoint to the forgetful functor U. □

Definition 15 ([26]).

A morphism is said to be a monomorphism in provided that for all -morphisms h and k such that , it follows that (i.e., f is left-cancellable with respect to the composition in ).

Dually, a morphism is said to be an epimorphism in provided that for all -morphisms h and k such that , it follows that (i.e., f is right-cancellable with respect to the composition in ).

Every morphism in a concrete category that is an injective function on underlying sets is a monomorphism; every morphism in a concrete category that is a surjective function on underlying sets is an epimorphism.

Theorem 8.

In IMSLatt, the monomorphisms are precisely the morphisms that are injective on the underlying sets, and the epimorphisms are precisely the morphisms that are surjective on the underlying sets.

Proof.

This proof is similar to Proposition 3.3 in the Reference [27]. □

Definition 16 ([26]).

If is a -morphism, then e is called a regular monomorphism if, and only if, there are -morphisms f and g such that is the equalizer of f and g.

Dually, if is a -morphism, then e is called a regular epimorphism if, and only if, there are -morphisms f and g such that is the coequalizer of f and g.

Theorem 9.

The forgetful functor preserves and reflects regular epimorphisms.

Proof.

Obviously, the forgetful functor preserves regular epimorphisms. We will prove that the forgetful functor reflects regular epimorphisms, which requires proving that the epimorphisms are precisely the regular epimorphisms in the category IMSLatt.

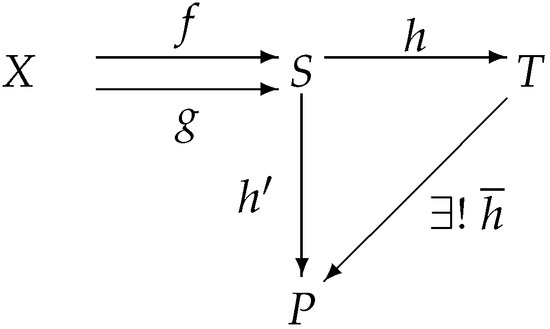

Let be an epimorphism in the category IMSLatt. Since the surjection is a regular epimorphism in the category Set, then the mapping h is a regular epimorphism in the category Set. This means that there is a set X and mappings such that is the coequalizer of f and g. Then, Figure 8 commutes.

Figure 8.

Coequalizer diagram.

For any , define two mappings and as follows:

According to the proof of Theorem 6, we know that mappings and are involutive m-semilattice homomorphisms. Since ,

Hence, .

Let mapping such that ; then, . Since is the coequalizer of f and g, this shows that there exists a unique mapping such that .

For any , since h is a surjective function, there are such that and . We have

(1) .

(2) .

(3) .

Thus, the mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

The above proof shows that is a coequalizer of f and g in the category IMSLatt. Then, Figure 9 commutes.

Figure 9.

Coequalizer diagram.

Therefore, the mapping h is a regular epimorphism in IMSLatt. □

Using Theorems 5, 7, and 9, we can obtain Theorem 10.

Theorem 10.

The category is algebraic.

4. The Colimit of the Functor in

Limits provide a highly abstract and unified way to describe various concrete mathematical constructions. The limit of a functor is a generalization of each of the notions of a “terminal object”, “equalizer”, “product”, and “intersection”. Therefore, the study of limits is very important for a category. The colimit is the dual definition of the limit. Limits are not only fundamental constructions within category theory itself but also powerful tools for connecting different mathematical fields and unifying various mathematical concepts. Limits and colimits have been systematically studied in some categories [30,31,32,33]. It is well known that to prove that a category is cocomplete, one must verify that the colimit of a functor from a small category to this category exists, and the construction of colimits relies on coproducts. Building coproducts in the involutive m-semilattice category is a complex and difficult task. In this study, we prove that a full subcategory of involutive m-semilattices is cocomplete, providing some insights for the proof of cocompleteness in the category of involutive m-semilattices.

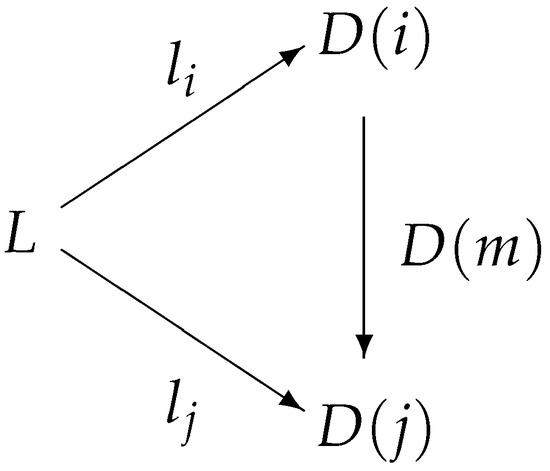

Definition 17 ([26]).

If I and are categories and is a functor, then a natural source for D is a source in such that for each , and for all morphisms , Figure 10 commutes.

Figure 10.

Natural source diagram.

Dually, a natural sink for D is a sink where is a natural transformation from D to the constant functor .

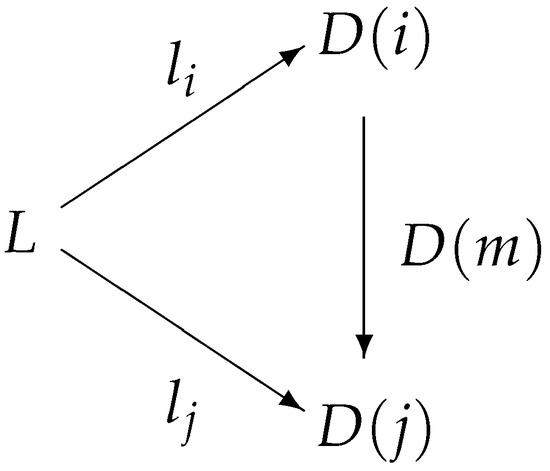

Definition 18 ([26]).

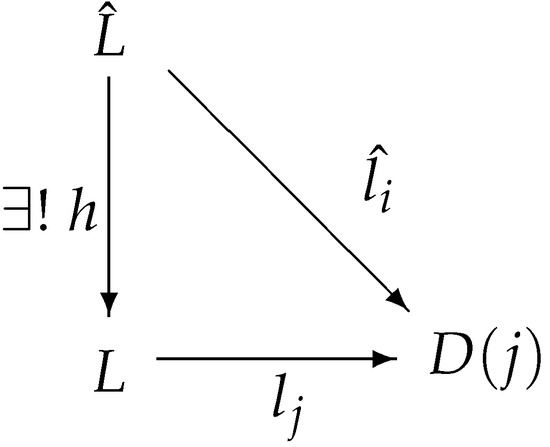

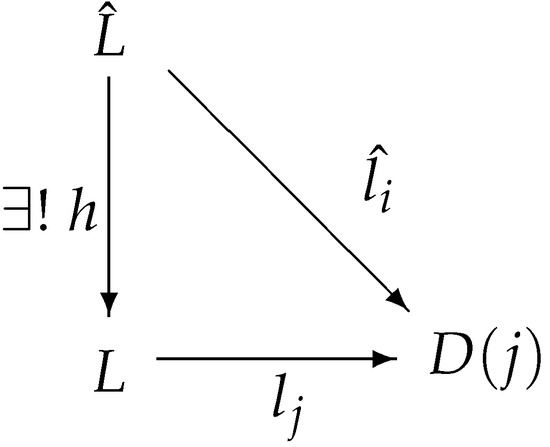

If is a functor, then a natural source for D is called a limit of D provided that if is any natural source for D, then there is a unique morphism such that for each , Figure 11 commutes.

Figure 11.

Limit diagram.

Dually, a natural sink is called a colimit of D provided that every natural sink for D factors uniquely through it.

Definition 19.

Let S be an involutive m-semilattice. , and I is a finite set. If S satisfies the condition (CD) , then is called an involutive mc-semilattice. It is clear that if S satisfies (CD), then S satisfies Definition 1(1).

Theorem 11.

Let S be an involutive mc-semilattice, and let R be a congruence of S. For any , we define ; ; ; . The mapping such that . Then, is an involutive mc-semilattice, and the mapping π is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 11 is similar to the proof of Theorem 4. □

Definition 20.

Let be a family of involutive mc-semilattices with a minimum element, and let be the Cartesian product of . For any , we define a mapping by , where denotes the minimal element of . Then, mapping is called a standard injection.

Lemma 3 ([20]).

Let be a family of involutive m-semilattices, and let be the Cartesian product of . , we define a semigroup multiplication "·" and an involutive operation on as follows: Then, is an involutive m-semilattice.

Theorem 12.

Let is a finite set }. , Then, is an involutive mc-semilattice under the pointwise order of the Cartesian product.

Proof.

The proof is similar to the proof of Lemma 3. □

Definition 21.

Let be a category whose objects are involutive mc-semilattices with a minimum element and whose morphisms are involutive m-semilattice homomorphisms. Obviously, the category is a full subcategory of .

Theorem 13.

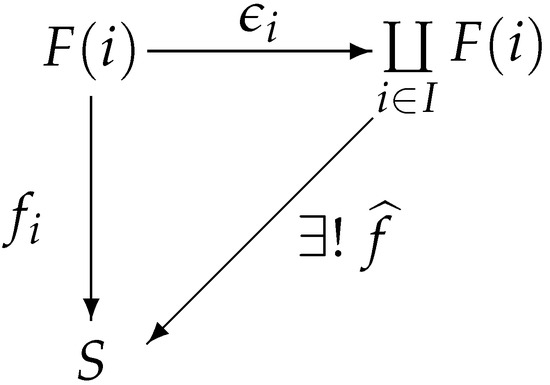

Let be a family of involutive mc-semilattices with a minimum element; then, is the coproduct of in , where and the mapping is an injection.

Proof.

We shall show that is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

,

(1)

Thus, .

(2)

Thus, .

(3)

Thus, .

Therefore, is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

Let S be an arbitrary involutive mc-semilattice with a minimum element 0. , mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism. We define by , . We first show that f is well defined for any . By the definition of , it follows that is a finite set. Since , mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism; then, (i.e., preserves the minimum element). Thus, the set is finite. Therefore, the supremum of the set in the semilattice S exists. This shows that f is well defined.

Next, we prove that f is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism.

; then,

(1) .

(2) , and by Definition 19, it follows that . Then, .

(3) .

In the following, we prove that for all . , . Then, Figure 12 commutes.

Figure 12.

Coproduct diagram.

Finally, we prove the uniqueness of the involutive m-semilattice homomorphism f that satisfies the conditions .

We assume that g is another involutive m-semilattice homomorphism that satisfies the above condition, i.e., , . Then, , we have

Therefore, is the coproduct of in . □

Definition 22 ([26]).

A category is said to be small provided that is a set.

Theorem 14.

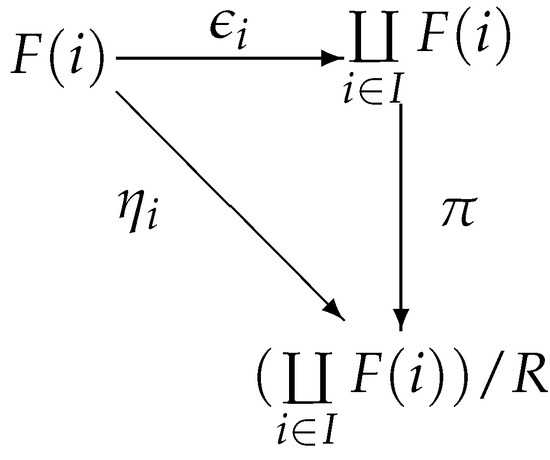

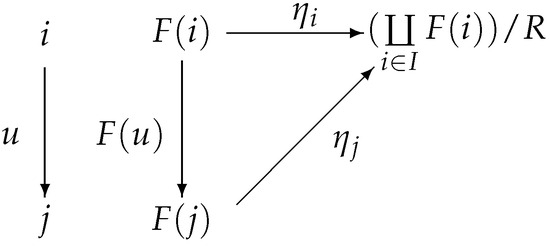

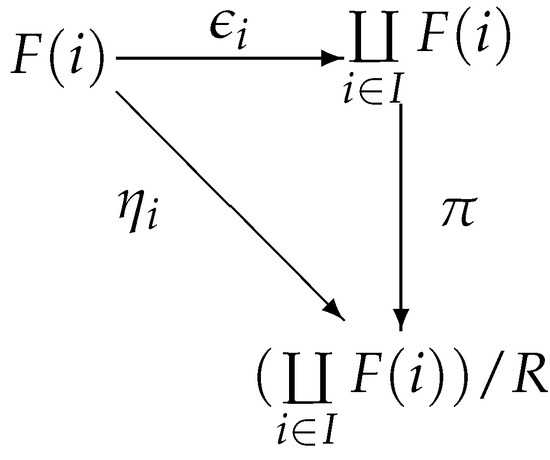

Let I be a small category, and let be a functor; then, the colimit of F is , where R is the smallest involutive m-semilattice congruence relation that contains the set , , is an injection, and is a projection.

Proof.

(1) We first show that is the natural sink of the functor F.

According to Theorems 11 and 13, it follows that projection and injection are both involutive m-semilattice homomorphisms. Then, the mapping is also an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism. Then, Figure 13 commutes.

Figure 13.

Canonical mapping diagram.

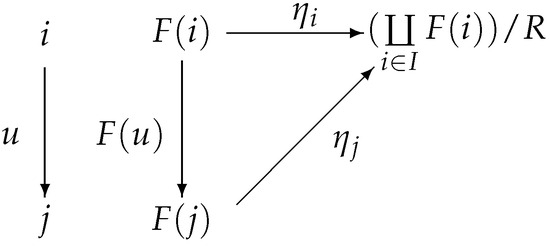

, . Because R is the smallest involutive m-semilattice congruence relation that contains the set , and , then ; thus, . Then, Figure 14 commutes.

Figure 14.

Natural sink diagram.

Therefore, is the natural sink of the functor F.

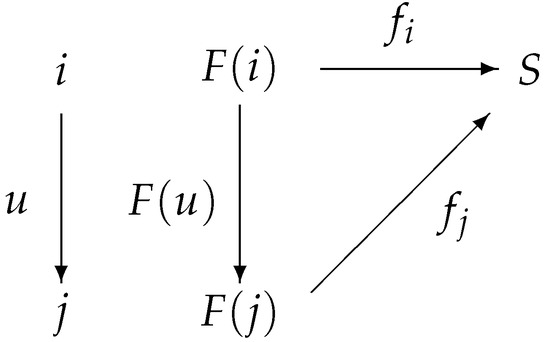

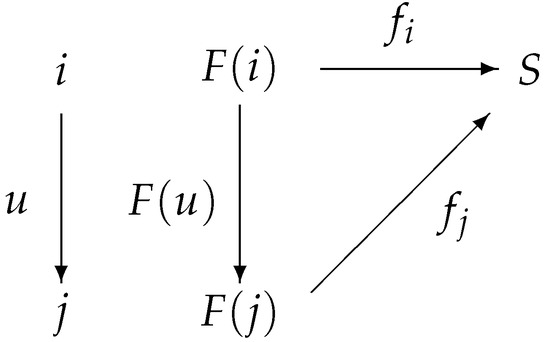

(2) Let S be an involutive mc-semilattice with a minimum element, let be a family of involutive m-semilattice homomorphisms, and let be the natural sink of the functor F. Then, , i.e., Figure 15 commutes.

Figure 15.

Natural sink diagram.

, we define such that . Since is a finite set, ; thus, the mapping is well defined.

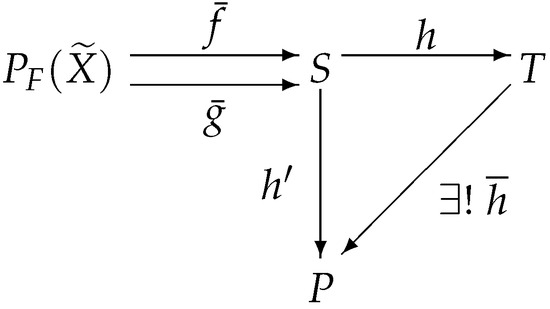

From Theorem 13, we know that is the coproduct of in , and there exists a unique involutive m-semilattice homomorphism satisfying ; then, Figure 16 commutes.

Figure 16.

Coproduct diagram.

Let , , ; then, , i.e., . Hence, . Since R is the smallest involutive m-semilattice congruence relation that contains the set , .

, if , then ; hence, . Therefore, , which implies that . Thus, the mapping is well defined. , , then . Thus, ; then, Figure 17 commutes.

Figure 17.

Colimit diagram.

(3) We shall show that the mapping is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism. , we have

(i) ; then, .

(ii) . By Definition 19, we know that . Hence, .

(iii) ; then, .

(4) We will prove the uniqueness of the involutive m-semilattice homomorphism that satisfies the conditions . Assuming that is another involutive m-semilattice homomorphism that satisfies , then . Hence, .

From (1), (2), (3), and (4), it can be concluded that is the colimit of the functor F. □

Corollary 1.

is cocomplete.

5. The Inverse Limit and Direct Limit in

Definition 23.

Let I be a downward-directed set; then, I can be taken for a category, where its objects are the elements in I. Let ; if , then a morphism is taken naturally in the category I.

A functor is called an inverse system in the category of involutive m-semilattices. An inverse system in IMSLatt can be described by the following statements without using the notion of a functor. Let I be a downward-directed set. For any and , there exists an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism . Further, for all satisfying . The triple is called an inverse system in IMSLatt.

Definition 24.

Let I be a downward-directed set, and let be an inverse system in IMSLatt. Then, the limit of F is called the inverse limit of the inverse system .

Dually, this holds for an upward-directed set in a direct system with a direct limit.

From the definitions of the inverse limit and direct limit in IMSLatt, it is clear that the inverse limits are defined to be particular limits, and direct limits are particular colimits. Inverse limits and directed limits have been extensively studied in some categories [27,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The following will give the inverse limit and direct limit in IMSLatt.

5.1. The Inverse Limit of the Inverse System in

Theorem 15 ([20]).

Let I be a small category, and let be a functor; then, the limit of F is , where such that . , , the mapping is projection, and .

Theorem 16.

Let I be a downward-directed set, and let be an inverse system in IMSLatt. Then, the inverse limit of inverse system F is , where if then such that , and , , is a projection (i.e., ).

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 16 is similar to the proof of Theorem 15 in Reference [20]. □

Suppose that and are two inverse systems in IMSLatt. Let and be the inverse limits of inverse systems F and G, respectively, where I and are downward-directed sets.

, , , are involutive m-semilattices. If and , then and are involutive m-semilattice homomorphisms. , , if and , , , , . The homomorphisms and are called the bonding mappings of the inverse systems F and G, respectively.

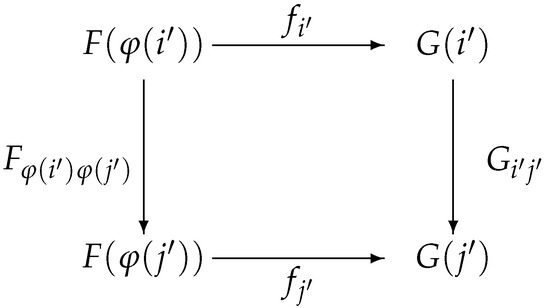

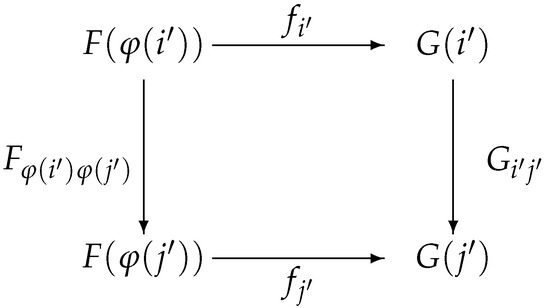

Definition 25 ([36]).

Let I be a downward-directed set, and . If , there is such that , and the set is called a downward cofinal subset of I.

Based on Definition 3.1 in [37], the definition of the mapping between two inverse systems can be given as follows.

Definition 26.

Let and be two inverse systems in IMSLatt. is called the mapping from inverse system F to inverse system G if it satisfies the following conditions:

(1) is an order-preserving mapping and is a downward cofinal subset of I.

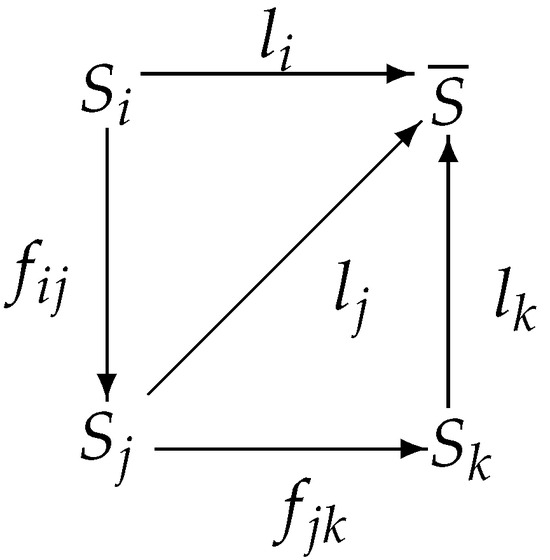

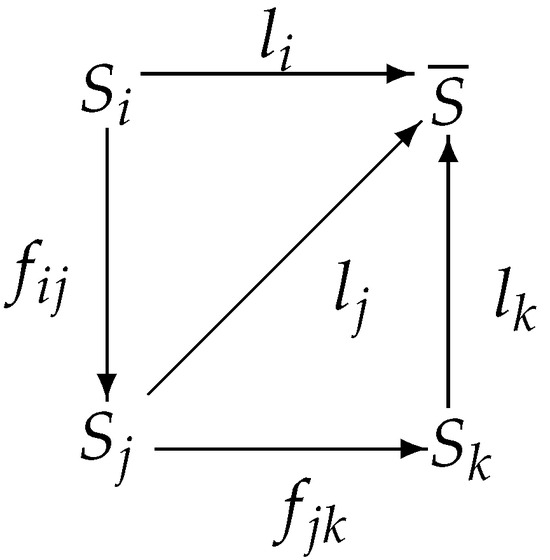

(2) , is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism, and , if , then , i.e., Figure 18 commutes.

Figure 18.

Commutative square.

Theorem 17.

Let and be two inverse systems in IMSLatt. is the mapping from inverse system F to inverse G. Then, the mapping induces an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism , where , , , and is a projection (i.e., ).

Proof.

, if , then . , by Definition 26(2) and Theorem 16, we know that ; then, . Thus, . This implies that there exists an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism such that . From Theorem 16, it follows that . Hence, f is well defined.

, ; then,

(1) . This implies that . Thus, f preserves the union.

(2) . This shows that . Thus, f preserves the semigroup operation ·.

(3) . Thus, f preserves the involution operation *.

Therefore, the mapping f is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism. □

Definition 27.

Let and be two inverse systems in IMSLatt. Let be a mapping from the inverse F to the inverse G. Then, the morphism induced above is called the limit mapping. It can be denoted by .

Theorem 18.

Let be a mapping from the inverse F to the inverse G. For any , if is a monomorphism, then the induced mapping is also a monomorphism.

5.2. The Direct Limit of the Direct System on IMSLatt

Definition 28 ([26]).

Let I be a set; if every subset of I has an upper bound, then I is called upward-bound.

Definition 29.

Let I be a upward-bound set. The functor is called a direct system in IMSLatt, where , and ; if , then is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism. For the convenience of the following description, let denote the mapping .

Lemma 4.

Let be a forgetful functor, and let be the coproduct of in the category of sets (i.e., the disjoint union of sets ). The binary relation on S is defined by the following: such that , , if, and only if, there is a such that , and . Let represent the equivalence class of S under relation "∼"; the order relation and three operations on S are defined by the following:

, such that and ,

(1) if, and only if, there is a that satisfies and .

(2) .

(3) .

(4) .

Then, is an involution m-semilattice.

Proof.

The proof of this theorem is similar to the proof of Proposition 2 in Reference [40]. □

Theorem 19.

Let I be an upward-bound set, and let be a direct system in IMSLatt. , if , and is an involutive m-semilattice homomorphism, then the direct limit of direct system D is , where is defined above in Lemma 5, , and the mapping represents the projection from S to its equivalence class .

Proof.

The proof of this theorem is similar to the proof of Theorem 14. □

Corollary 2.

IMSLAtt is directed and complete.

Theorem 20.

Let I be an upward-bound set, let functor be a direct system in IMSLatt, and let be the direct limit of direct system D. , if , mapping is a monomorphism; then, is also a monomorphism.

Proof.

Let , . Figure 19 commutes. Then, . Since mapping is a monomorphism. Thus, , i.e., . Because I be an upward-bound set, there exists such that , . Since mapping is a monomorphism. Then, . This means that . Thus, is a monomorphism. □

Figure 19.

Commutative triangle.

6. Conclusions

This paper mainly conducts an in-depth study on the properties of the category of involutive m-semilattices. The concepts of the nucleus and congruence are introduced. The concrete structure of a coequalizer in the category of involutive m-semilattices is obtained. It is shown that the category of involutive m-semilattices is algebraic. Based on the study of limits, we conduct a systematic investigation of limits within the category of involutive m-semilattices, obtaining the specific forms of colimits, inverse limits, and directed limits. These findings expand new horizons for the study of involutive m-semilattice theory and provide a theoretical foundation for the research on the applications of involutive m-semilattices. The research ideas and methods presented in this paper hold application value in the study of lattice structures, topological structures, fuzzy mathematics, rough sets, and logical algebra, among others, which represent the directions for future research.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Program Funded by the Shaanxi Provincial Education Department (grant number: 17JK0510).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editors and the reviewers for their valuable comments and helpful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mulvey, C.J. Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; Volume 12, pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey, C.J.; Resende, P.; Miraglia, F. A noncommutative theory of Penrose tilings. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2005, 44, 655–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetter, D. Quantales and (non-commutative) linear logic. J. Symb. Log. 1990, 55, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, J.Y. Linear logic. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1987, 50, 1–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamide, N. Quantized linear logic, involutive quantale and strong negation. Stud. Log. 2004, 77, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruml, D.; Resende, P. On quantales that classify C*-algebra. Cah. Topol. Geom. Categ. 2004, 45, 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Conigrlio, M.E.; Miraglia, F. Non-commutative topology and quantales. Stud. Log. 2000, 65, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.X.; Zhang, G. Sober topological spaces valued in a quantale? Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2002, 444, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, G.J.; Höhle, U.; Kubial, T. Basic concepts of quantale-enriched topologies. Categ. Struct. 2021, 29, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyov, S. On the category Q-Mod. Algebra Universalis 2008, 58, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Zhou, M.; Li, Z.H. Projectives and injectives in the category of quantales. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 2002, 176, 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, X.L.; Liu, X.C. A Categorical Equivalence between logical Quantale Modules and Quantum B-modules. Math. Log. Q. 2023, 69, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.Y.; Xu, L.S. Roughness in quantales. Inf. Sci. 2013, 220, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, K.I. Quantales and Their Applications; Longman: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, B. Ideals of m-semilattices. J. Northwest Univ. 2015, 45, 202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, B. Rough fuzzy ideals of m-semilattices. J. Jilin Univ. Ed. 2015, 53, 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, B.; Han, S.W. Roughness in m-semilattices. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2016, 30, 2331–2338. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.Q.; Zhao, B. Filtersin m-semilattices and their Related topological properties. J. Ji Lin Univ. Ed. 2022, 60, 568–575. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, F.F.; Han, S.W. Remark on coherent quantales. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2012, 48, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.H.; Zhang, X.T.; Xia, X.G. Special elements, ideals in involutive m-semilattices and Its categorical properties. J. Shandong Univ. Sci. 2024, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N. Generalized M-P inverse of m-semilattice matrix. J. Taiyuan Norm. Univ. Sci. Ed. 2018, 17, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, J.W.; Lan, A.Y. Codimension of compact M-semilattices. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1975, 52, 406–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kourinnyy, H.C. Weak representability of M-semilattices. Algebra Univ. 1996, 36, 357–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.S.; Zhao, B. The category of M-semilattices. Northeast Math. J. 1998, 14, 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Botur, M.; Paseka, J.; Lekár, M. Foulis m-Semilattices and Their Modules. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.01405 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Herrilich, H.; Strecker, E. Category Theory; Heldermann Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.B.; Zhao, B. Algebric properties of category of quantales. Acta Math. Sin. 2006, 49, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.W.; Zhao, B.; Wang, K.Y. Some further results on free quantale algebras. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2020, 382, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuchok, A.V.; Koppitz, J. Free weakly k-nilpotent n-tuple semigroups. Turk. J. Math. 2024, 48, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlicki, A. Computable Limits and Colimits in Categories of Pratial Enumerated Sets. Math. Log. Q. 1993, 39, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M. Limit Structures over Completely Distributive Lattices. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2002, 132, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heunen, C.; Karvonen, M. Limits in Dagger Categories. Theory Appl. Categ. 2019, 34, 468–513. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, M. Limits in the Category Seg of Segal Topological Algebras. Proc. Est. Acad. Sci. 2022, 71, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G. Inverse Limits in Category LTop (I). Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1999, 108, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. The Inverse Limit in the Category of Topological Molecular Lattices. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2001, 118, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, F. Inverse Systems and Inverse Limits in the Category of Plain Textures. Topol. Its Appl. 2016, 201, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, J. Direct limits of meet-continuous lattices. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 1982, 23, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzig, T.; McRae, R.; Yang, J.W. Direct Limit Completions of Vertex Tensor Categories. Commun. Contemp. Math. 2022, 241, 2150033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; de Jeu, M. Direct limits in categories of normed vector lattices and Banach lattices. Positivity 2023, 27, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. The Directed Limit in the Category of Involutive Quantale. Yantai Norm. Univ. J. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 22, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).