Abstract

This paper investigates a class of distributed fractional-order stochastic differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion with a Hurst parameter . By employing the Picard iteration method, we rigorously prove the existence and uniqueness of solutions with Lipschitz conditions. Furthermore, leveraging the Girsanov transformation argument within the metric framework, we derive quadratic transportation inequalities for the law of the strong solution to the considered equations. These results provide a deeper understanding of the regularity and probabilistic properties of the solutions in this framework.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, stochastic differential equations have significantly attracted the attention of many researchers due to their wide applications in economics, biology, computing, engineering and chemistry (see [1,2,3,4]). The fractional derivative of a constant is not equal to zero, unlike the classical derivative. It is evident that, within the domain of fractional derivatives, the Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative is the most prevalent and significant. Almost all other definitions of fractional derivatives are available as the special cases of Riemann–Liouville fractional derivatives. The development of theoretical frameworks and their subsequent practical applications have resulted in a marked increase in interest in all aspects of fractional (stochastic) differential equations (see, e.g., [5,6,7,8,9]). A constant-order fractional differential equation is unable to adequately reflect the inherent uncertainty present in the data, thus necessitating the introduction of variable-order operators to accommodate the structural changes occurring in the surrounding context. Numerous significant results have been obtained pertaining to both variable-order fractional derivatives and variable-order (stochastic) fractional differential equations, for which we can refer to [10,11,12,13,14]. Furthermore, a distributed-order fractional derivative is defined by

where is a probability density function (see [10]). The objective is to provide a framework for creating data-driven fractional differential operators that can be used to fit data directly from real measurements. This will result in a more effective model of uncertainties [15,16]. is the Riemann–Liouville fractional differential operator defined by

Over the past few years, there has been a marked increase in the interest surrounding the study of fractional Brownian motion and associated processes. This trend has been driven by their applications in diverse fields, including finance, telecommunications, image processing, and turbulence. A fractional Brownian motion of Hurst parameter is a centered Gaussian process with the covariance function

When , the fractional Brownian motion (fBm) reduces to standard Brownian motion, whose increments are independent. For , the process loses both the semimartingale property and Markovianity due to its non-local covariant structure. This behavior has spurred significant research on stochastic differential equations driven by fBm; we refer to [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] for comprehensive reviews.

Motivated by the above discussion, the aim of this paper is to present a discussion of the following distributed-order fractional stochastic differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion:

with initial condition . Here, is a constant and is a fractional Brownian motion with Hurst parameter , and are all progressively measurable with further conditions specified in the sequel. Consequently, the definition of the fractional integral and derivative can be utilized to reformulate

where is a stochastic process and is -measurable. The following definition applies to the kernel :

Our first result (Theorem 1) proves the well-posedness of (4) through a fractional Picard scheme, extending classical techniques to the distributed-order case.

Meanwhile, transportation inequality (TCI) provides an error analysis and an optimization basis for engineering problems such as physical simulation, signal processing, and material design by quantifying differences among probability distributions. Its core value is to transform the statistical behavior of complex systems into computable distributed matching problems, thus guiding algorithm improvement and practical application. TCIs for stochastic processes have attracted growing interest, owing to their connections with Tsirelson-type inequalities, Hoeffding-type inequalities [25,26,27], and the concentration of empirical measures [28,29]. The Girsanov transformation argument is one of the most effective methods for establishing transportation inequality [25]. Most of the results concerning the TCI of stochastic processes are derived thanks to the Girsanov transformation argument. For instance, as outlined in [26,27], the study focuses on diffusion processes on , while [30] examines multidimensional semimartingales. The literature further extends to SDEs with pure jump processes, as detailed in [29], and [31] for SDEs driven by a fractional Brownian motion, [32] for stochastic delay evolution equations driven by fBm with Hurst parameter , and [33] for neutral stochastic evolution equations driven by fBm with Hurst parameter .

Now, our analysis focuses on the following inequalities. The discrepancy between probability measures is assessed via the transportation metric, formally defined as the Wasserstein distance. Let be a metric space equipped with a -field B such that the distance d is -measurable. Given and two probability measures and on E, the Wasserstein distance is defined by

where denotes the totality of probability measures on with the marginal and The relative entropy of with respect to is defined as

As is customary, the relation is written as for this particular instance. The cases and have been most extensively studied. The distinctive properties of hold significant theoretical importance. Therefore, the second objective of this work is to derive transport inequalities (TCIs) for the solution law of Equation (4) in the metric via Girsanov transformation.

The framework of this paper is as follows: In Section 2, the fractional Brownian properties of fractional Brownian are presented, along with the assumptions and auxiliary results that are employed to substantiate the mathematical estimates in subsequent sections. In Section 3, we complete the demonstration of existence and uniqueness of the solution to the equation. In Section 4, we prove of Equation (4) under the metric.

2. Preliminaries

This section is dedicated to the collection of relevant notions, conceptions and lemmas pertaining to Wiener integral with respect to fractional Brownian motion. For further information, we refer to [34,35,36]. And then, we make some assumptions for the model. In this paper, unless explicitly indicated otherwise, we consider the complete probability space to be a filtration satisfying the standard conditions, namely that it is right-continuous and that contains all empty sets. The symbol denotes the expectation under the probability measure . Stochastic processes are specified on the set . If , then is the absolute value. The symbol K is employed to denote any constant, the value of which is of no consequence and is subject to variation from one line of argument to another.

2.1. Fractional Brownian Motion and Wick Product

Consider a finite time horizon and let denote a one-dimensional fractional Brownian motion (fBm) with Hurst parameter . It should be acknowledged that, in the event that , the Wiener integral representation of is given by the following expression:

where is a Wiener process. The kernel function is given by

and , in which is the Beta function, and . For a more comprehensive overview of the fractional Brownian motion (fBm), the reader is referred to the following works [34,37,38].

Let denote the set of all finite multi-indices , where are non-negative integers for all . Denote , and . For , the Hermite polynomials are defined as follows:

and Hermite functions

Let be the Schwartz space of rapidly decreasing infinitely differentiable real-valued functions and let be the dual space of . Setting

to be the product of Hermite polynomials. Consider a square-integrable random variable

Thus, following [34,39], every admits a unique representation

and

where and . Their Wick product [36] is defined by

2.2. Malliavin Derivative

Let be the space of all random variables , such that

and let

where

Let . The -derivative of a stochastic variable in the direction of is defined by

if the limit exists in . Moreover, if there exists a process , such that

for all , then F is said to be -differentiable.

Let be the family of stochastic processes on such that if and F is -differentiable, the trace of exists and , and for each sequence of partitions such that , as . Moreover,

and

as . Here,

Next, we define a stochastic integral with respect to fBm.

Let be a stochastic process such that , then the stochastic integral satisfies by

where .

(I) According to Theorem in [36], if , then the stochastic integral satisfies , and

By Definition in [36], the above stochastic integral can be extended as follows:

where is a given function such that is -integrable in . Here, is the fractional Hida distribution space defined by Definition in [36]. And in this extension, the integral on an interval can be defined by

(II) For , the definition of stochastic integrals and can be found in textbooks (cf., Chapter 3 of the work by Karatzas and Shreve [40]).

According to Remark 1 and Lemma 2 in [41], the following lemma is obtained.

Lemma 1.

Let be an fBm with Hurst index , and let a stochastic process Then, for every ,

Lemma 2

(Discrete Jensen’s inequality). For , we have

Lemma 3

(Borel–Cantelli lemma). Let be events in a probability such that , then

where is defined by

Lemma 4

(Generalized Gronwall inequality). Let be a non-negative locally integrable function on and be a non-negative constant. Suppose is a non-negative locally integrable function on with

where

In particular, if is non-decreasing, then

where represents the Mittag–Leffler function

In this paper, we proceed with the following assumptions:

- (H1) and on for some and .

- (H2) There exists such that for ,

- (H3) There exists such that for all , ,

3. Existence and Uniqueness

Theorem 1.

Under Assumptions (H1)–(H3), the stochastic differential equation driven by fBm (4) admits a unique solution on the time interval [0,T]:

where the constants and Q1 are given by

Proof.

Then, we observe that

By using Jensen’s inequality (7) with , we obtain

The existence and uniqueness theorem is demonstrated through the utilization of Picard iteration, a method employed to prove the aforementioned theorem. The following definition is required: a sequence of processes by , and for , the following apply. Existence:

- (1)

- Structural Picard sequence:

According to (12) and Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, it follows that

By applying Cauchy–Schwarz inequality and Assumption (H2), it follows that

where L is the Lipschitz constant. According to Lemma 1 and Assumption (H2) we obtain

Then, we have

where

To proceed, it is routine to derive

For the sake of clarity, the following definition is proposed for for all :

Thus, by (14), for all , we get

For , the linear growth condition (H3) can be argued instead of the Lipschitz condition:

- (2)

- Prove that the sequence converges uniformly: Then, for any , we obtain by mathematical induction thatby observing that the series defined on the right-hand side of the equation converges to (8). At first, let , , ,Secondly, we obtain

- (3)

- Verify that the limit function is a solution: According to the Borel–Cantelli lemma, converges uniformly on [0,T] to , taking the limit for (9):So, is the solution of Equation (4). So the proof of existence is complete.

Uniqueness: Assume that there exist two solutions z and to Equation (4), obtained by a similar derivation as in (14):

Applying Gronwall inequality, one almost necessarily obtains .

Moment estimates: We subsequently proceed to provide moment estimates for Equation (4). Utilizing the Jensen’s inequality (7) with , Assumption (H3), Lemma 1, Lemma 2, Picard’s sequence, and the property of ,

where

Applying Lemma 4 (Gronwall inequality) with , we obtain the final result when . The proof is complete. □

4. Transportation Inequalities for (4)

Theorem 2.

Let be the probability measure of the solution process of Equation (4). Under Assumptions (H1)–(H3), the probability measure satisfies on the metric space with

where

When using the metric,

Proof.

- (1)

- Construct the measure transformation.

Suppose is the probability measure on of the solution process of Equation (4) on , and is an arbitrary probability measure on K such that Define

to be a probability measure on Building upon the entropy definition, we apply measure transformation techniques combined with Equation (16) to derive

From [42], there exists a predictable process satisfying

and

- (2)

- Define a new noise process.

By the Girsanov theorem, it is known that the process defined by

is a Brownian motion about on the probability space . According to the transfer principle, -fractional Brownian motion is defined as

where the operator is defined by

- (3)

- Rewrite the original equation.

As a result, under the measure ,

- (4)

- Construct coupling equation.

We then consider the solution y of the following equation under :

- (5)

- (Control Wasserstein distance.

It follows that under , the distribution of is Therefore, under is a pair of couplings of . We can then get

The following distance between z and y with respect to can be obtained from (17) and (18):

Firstly, a similar way to ,

For , using a similar method to , we get

And, using a similar method to , we have

By Assumption (H3) and Thereom 1, for every , we can obtain

For , it follows by the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality that

Next, we estimate ds. By the definition of , we have

where

and is the standard Beta function.

Due to

and the property of the Beta function, we obtain

Then, substituting Equation (25) into Equation (24),

Thus, applying (23) and (26), we can obtain that

Applying (20)–(22), (27) and Jensen’s inequality, we can get

Combining the Gronwall inequality, we have

where

So, we can write it as

Then,

with . The proof is complete. □

5. Example

In this section, we will use a numerical example to demonstrate the results obtained in the previous sections.

Example 1.

Let us consider the following distributed-order fractional stochastic differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion.

For the coefficients of (28), we set the following:

- (1)

- When is a probability density function, defineHere, we choose and . Obviously, satisfies (H1), that is, on and

- (2)

- When , define . Obviously, satisfies (H2), that is, for all ,

- (3)

- (When , define . Obviously, satisfies (H3), that is, for all ,

- (4)

- with .

- (5)

- is a fractional Brownian motion with .

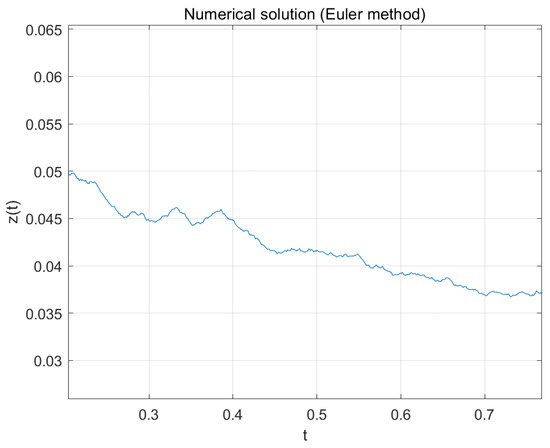

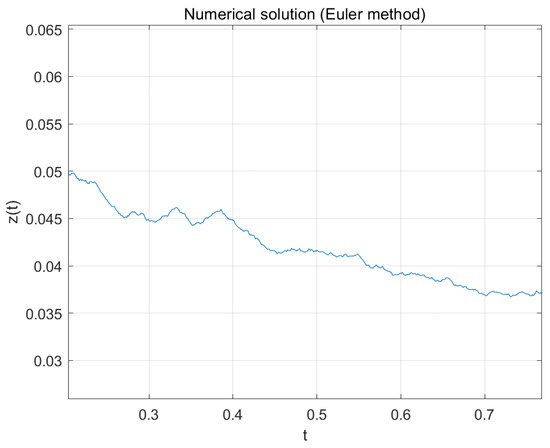

By substituting the above coefficients into (28), we have

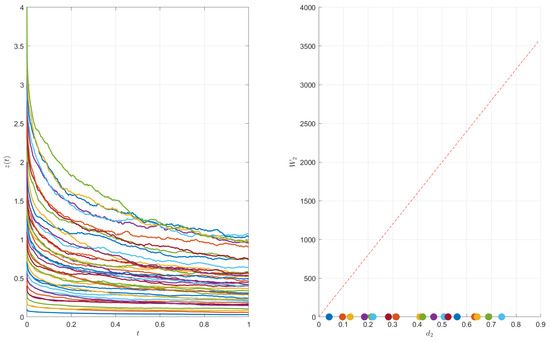

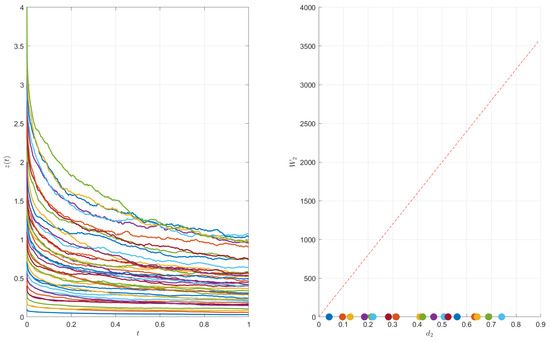

From Equation (29), . It follows from Theorem 2 that the transportation inequality holds when holds. Taking as the step, Euler’s method was used to obtain the approximate solution of the equation, as shown in Figure 1. As shown in the left side of Figure 2, we selected 20 groups of paths with different initial values. The right graph of Figure 2 shows and the theoretical upper bound associated with these 20 sets of paths. From the graph, we can see that is much smaller than , which further supports our theoretical result (Theorem 2).

Figure 1.

Euler method with step size . Partial path diagram of .

Figure 2.

Path diagram (left), and theoretical upper bound (red line) (right).

Author Contributions

Methodology, G.X.; Validation, L.X.; Formal analysis, Z.L.; Writing—original draft, G.X.; Writing—review and editing, L.X.; Supervision, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.11901058) Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (No. 2021CFB543).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no confficts of interest.

References

- Yang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, H. A variably distributed-order time-fractional diffusion equation: Analysis and approximation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2020, 367, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Park, J.H.; Cao, J. Adaptive synchronization of fractional-order output-coupling neural networks via quantized output control. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 3230–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diethelm, K. The Analysis of Fractional Differential Equations. An Application-Oriented Exposition Using Differential Operators of Caputo Type; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, Z. The finite-time blow-up for semilinear fractional diffusion equations with time ψ-Caputo derivative. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2022, 32, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadova, A.; Mahmudov, N. Existence and uniqueness results for a class of fractional stochastic neutral differential equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbas, A.; Srivastava, H.; Trujillo, J. Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 204. [Google Scholar]

- Samko, S.; Kilbas, A.; Marichev, O. Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: Theory and Applications; Gordon and Breach Publishers: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Li, Z. Stochastic fractional evolution equations with fractional brownian motion and infinite delay. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 336, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, H. Strong convergence of a Euler-Maruyama scheme to a variable-order fractional stochastic differential equation driven by a multiplicative white noise. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 142, 110392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Du, N.; Yang, Z. A distributed-order fractional stochastic differential equation driven by Lévy noise: Existence, uniqueness, and a fast EM scheme. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2023, 33, 023109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.; Hartley, T. Variable order and distributed order fractional operators. Nonlinear Dyn. 2002, 29, 57–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Hollkamp, J.; Semperlotti, F. Applications of variable-order fractional operators: A review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20190498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. Variable-order fractional differential operators in anomalous diffusion modeling. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2009, 388, 4586–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chang, A.; Zhang, Y. A review on variable-order fractional differential equations: Mathematical foundations, physical models, numerical methods and applications. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2019, 22, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, K.; Ford, N. Numerical analysis for distributed-order differential equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2009, 225, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F.; Pagnini, G.; Gorenflo, R. Some aspects of fractional diffusion equations of single and distributed order. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 187, 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Boufoussi, B.; Hajji, S. Neutral stochastic functional differential equations driven by a fractional Brownian motion in a Hilbert space. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2012, 82, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, T.; Garrido-Atienza, M.; Taniguchi, T. The existence and exponential behavior of solutions to stochastic delay evolution equations with a fractional Brownian motion. Nonlinear Anal. Theory Methods Appl. 2011, 74, 3671–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Shift Harnack inequality and integration by parts formula for functional SDEs driven by fractional Brownian motion. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2016, 144, 2651–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, L. Stochastic averaging for two-time-scale stochastic partial differential equations with fractional Brownian motion. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2019, 31, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhou, J. Viability for coupled SDEs driven by fractional Brownian motion. Appl. Math. Optim. 2021, 84, 55–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Xiang, J.; Wu, J. Averaging principle for distribution dependent stochastic differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion and standard Brownian motion. J. Differ. Equ. 2022, 321, 381–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lian, Q.; Wu, J. A strong averaging principle rate for two-time-scale coupled forward–backward stochastic differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion. Appl. Math. Optim. 2023, 88, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Ren, J. A support theorem for stochastic differential equations driven by a fractional Brownian motion. J. Theor. Probab. 2022, 36, 728–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellout, H.; Guillin, A.; Wu, L. Transportation cost-information inequalities and applications to random dynamical systems and diffusions. Ann. Probablity 2004, 32, 2702–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Z. Talagrand’s T2-transportation inequality w.r.t. a uniform metric for diffusions. Acta Math. Appl. Sin. 2004, 20, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Z. Talagrand’s T2-transportation inequality and log-sobolev inequality for dissipative SPDEs and applications to reaction-diffusion equations. Chin. Ann. Math. Ser. B 2006, 27, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Transportation inequalities for stochastic differential equations with jumps. Stoch. Processes Their Appl. 2010, 120, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Transportation inequalities for stochastic differential equations of pure jumps. Ann. l’IHP Probab. Stat. 2010, 46, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S. Concentration for multidimensional diffusions and their boundary local times. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 2012, 154, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussereau, B. Transportation inequalities for stochastic differential equations driven by a fractional Brownian motion. Bernoulli 2012, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, J. Transportation inequalities for stochastic delay evolution equations driven by fractional Brownian motion. Front. Math. China 2015, 10, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufoussi, B.; Hajji, S. Transportation inequalities for neutral stochastic differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion with Hurst parameter less than 1/2. Mediterr. J. Math. 2017, 14, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishura, Y.; Mishura, I. Stochastic Calculus for Fractional Brownian Motion and Related Processes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Øksendal, B. Fractional white noise calculus and applications to finance. Infin. Dimens. Anal. Quantum Probab. Relat. Top. 2003, 6, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagini, F.; Hu, Y.; Øksendal, B.; Zhang, T. Stochastic Calculus for Fractional Brownian Motion and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alos, E.; Mazet, O.; Nualart, D. Stochastic calculus with respect to Gaussian processes. Ann. Probab. 2001, 29, 766–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascanu, A. Differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion. Collect. Math. 2002, 53, 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, H.; Øksendal, B.; Ubøe, J.; Zhang, T.; Holden, H. Stochastic Partial Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Karatzas, I.; Shreve, S. Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 113. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Pei, B.; Wu, J. Stochastic averaging principle for differential equations with non-Lipschitz coefficients driven by fractional Brownian motion. Stochastics Dyn. 2017, 17, 1750013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato, G.; Zabczyk, J. Stochastic Equations in Infinite Dimensions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).