Abstract

As a generalization of the symmetry of the stress tensor of continuum mechanics, the paper investigates symmetry properties arising in models of magneto- and electro-mechanical interaction. First, the balance of angular momentum is considered, thus obtaining a symmetry condition that is applied as a mathematical constraint on admissible constitutive equations. Next, thermodynamic restrictions are also investigated and, among others, a further symmetry condition is determined. The joint validity of the two symmetry conditions implies that the dependence on electromagnetic fields has to be through variables involving deformation gradients. These variables constitute two classes that prove to be Euclidean invariants. The simplest selection of the variables is just that of Lagrangian fields in the literature. Furthermore, the variables of one class allow a positive magnetostriction and of the other one allow a negative magnetostriction. Some applications to (NO) Fe-Si are outlined. The use of entropy production as a constitutive function allows generalization to dissipative and heat-conducting electromagnetic solids.

1. Introduction

Electromagnetism in deformable bodies is a source of interesting problems about the appropriate formulation of balance equations. Further problems arise in connection with the selection of fields for the characterization of constitutive equations; references [1,2,3] show a view of the variety of formulations for electromagnetism in deformable bodies. Their differences remain even though an appeal is made to the restrictions placed by the second law of thermodynamics.

Balance equations are often based on the assumption that the total stress in a body is the sum of the mechanical stress and the (Maxwell) electromagnetic stress, possibly with a symmetry requirement for the total stress. Yet, the adopted Maxwell stress suffers from non-uniqueness. This trouble is overcome if, as observed in [4], there is no need to adopt any form of the Maxwell stress within the material.

The purpose of this paper is to revisit the subject of constitutive equations in electromagnetism on the basis of the symmetry requirements arising from the balance of angular momentum.

As is customary, it is assumed that couple density occurs due to the polarization and the magnetization interacting with the electric field and the magnetic field . Hence, the balance of angular momentum is established by involving surface and volume terms; the stress is, in fact, the mechanical stress, while the couple is of an electromagnetic nature. The balance results in a symmetry condition that is independent of the selected body force.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the symmetry condition obtained and derive the consequences by regarding the symmetry as a mathematical constraint. Furthermore, we investigate the restrictions placed by thermodynamics and look for schemes where the results are consistent with the symmetry given by the balance of angular momentum. This approach proves profitable in that it leads to two classes of admissible variables. Indeed, upon the balance of energy, the statement of the second law is made explicit for electromagnetic solids. A further symmetry condition emerges from the second law. It then follows that the symmetry is satisfied if, in three-dimensional models, the dependence on electromagnetic fields is described by variables that involve the deformation gradient. These variables prove to be Euclidean invariants. Furthermore, among these variables, the simplest ones turn out to be the Lagrangian fields often applied in the literature.

As an interesting generalization, the solid is allowed to be dissipative and heat-conducting. Using a representation formula for vectors and tensors, we then find expressions of the stress tensor and equations for the heat flux. Though Lagrangian variables are involved, the stress turns out to be expressed by Eulerian fields and includes the dyadic product of fields induced by the electromagnetic couple.

Notation

Let be the three-dimensional region occupied by the body at the current time t. Denote by the position vector of a point in , relative to a chosen origin, O. Compact notation for vectors and tensors is used. When convenient, we consider the components relative to a chosen orthonormal right-handed basis, ; the sum over twice-repeated indices is understood.

For any two tensors, and , we mean that . The symmetric and skew-symmetric parts of the tensor are respectively denoted by

Sym and Skw are the sets of symmetric and skew-symmetric tensors. The symbol denotes the gradient operator, ⊗ is the dyadic product, and is the identity tensor.

Electromagnetic quantities are denoted by sans-serif letters; is the electric field, is the magnetic field, is the polarization, is the electric displacement, is the electric current density, and is the free charge density. The constants C2/N·m2 and N/A2 are the permittivity and the permeability of free space.

As to thermodynamic quantities, is the internal energy density, is the entropy density, is the free energy density, is the absolute temperature, is the heat flux, and is the entropy production. As to mechanical quantities, is the mass density, is the velocity, is the deformation gradient, , is the Green–Lagrange strain tensor, is the velocity gradient, , is the stretching, is the spin, is the body force density, and is the stress tensor.

2. Balance Equations and Symmetry in Electromagnetic Solids

This section investigates the balance equations for an electromagnetic solid with the purpose of deriving some symmetry properties.

2.1. Electromagnetic Fields and Forces in Matter

Under the action of an electric field, , an induced dipole moment of atoms arises because the regions of positive and negative charges are centered at different points. Some molecules, called polar, have built-in permanent dipole moments. Additionally, dipoles feel a force and a torque [5,6]. By viewing the dipole as consistent with two charges, and , at positions displaced by , the dipole is found to experience the force and the torque given by

The polarization is defined as the electric dipole moment per unit volume while is the electric dipole moment per unit mass.

The magnetic dipole moment is usually thought of via Ampère’s model as a current loop, thus leading to the force and the torque as follows [6] (ch. 6):

In stationary conditions, , and then

The magnetization is defined as the magnetic dipole moment per unit volume while is the magnetic dipole moment per unit mass.

According to the Minkowski formulation, the displacement electric vector and the magnetic induction are given by

and the fields and are subject to Maxwell’s equations:

where is the electric current and is the free charge density. Equations (3) and (4) are, in fact, balance equations accounting for the laws of electromagnetism.

2.2. Balance of Linear and Angular Momentum

Electromagnetic solids are viewed as (solid) continua endowed with the magnetization and the polarization . The solids are taken to be subjected to a stress tensor, , an electric field, , and/or a magnetic field, , in addition to a specific body force.

The stress tensor originates by the modeling of a surface force density per unit area, , with being the unit outward normal to the surface. The balance of linear momentum and Cauchy’s theorem (cf., e.g., [7] (§ 19.5)) imply the existence of a stress tensor, , such that

Henceforth, we consider a sub-region, , convecting with the body. Hence, for any specific density function, , we can write the Reynolds transport relation in the form

The mass density is denoted by while is the referential mass density.

We denote by and the mechanical and electromagnetic force density, per unit volume. The local form of the equation of motion can be written as follows [8] (§ 69):

where . For definiteness, we might take in the form

however, the present developments hold irrespective of the form of .

In light of (1) and (2), we take

as the torque, or body couple, per unit volume, of an electromagnetic nature. The current density has no significant effects on the torque (see, e.g., [3] (sec. V.B)). Really, torques arise in current-carrying loops in a magnetic field. This is not macroscopically the case in electromagnetic solids, and hence, the contribution of to the torque density is neglected.

For the sake of generality, we allow also for a body couple density, , per unit mass, of a non-electromagnetic character. Hence, the whole electromagnetic torque in a region, , determined by the body couples, is

For definiteness, as is shown in the next section, the dependence of constitutive properties on the temperature gradient may result in a body couple.

Let be the position vector of a point of the body relative to a fixed base point, . Denote by the constant vector the position vector of the origin O relative to so that

The balance of angular momentum is assumed in the form

The integral on the boundary is computed in a strictly vector form. Notice that

By using the permutation property , upon inner-multiplying the integral by a constant vector, , we have

Algebraically, any vector, say, , is in one-to-one correspondence with a skew-symmetric tensor, say, . Let be the alternating symbol, which is defined by (see Appendix A)

Hence, any skew tensor is obtained through a unique vector, , in the form

the correspondence can be inverted:

These relations show the one-to-one correspondence between the vector and . Incidentally, with these relations, is twice the axial vector of (see [7] (p. 15); [9] (p. 957)).

Now, let be the vector given by

and hence in one-to-one correspondence with the skew part of . Since , then by a direct calculation, it follows that

Hence, we obtain

Thus, the arbitrariness of implies that (see Appendix A)

Notice that , and then, in light of the Reynolds’ transport relation (5), we can write

Throughout, it is assumed that the region is arbitrary and the pertinent integrand is a continuous function of the position . Hence, using Equation (6), it follows from (9) that

Equation (12) can be given a tensor form. Let be the skew tensor associated with , viz.

Then, Equation (12) can be written in the form

or, in tensor notation,

which implies that

The symmetry condition (14) is a constraint on the evolution of the body; at any point and time t, the fields and must satisfy the requirement (14). If and or , then (14) simplifies to

If, furthermore, is collinear to and is collinear to , then (14) becomes the classical condition of continuum mechanics.

2.3. Remarks on the Symmetry Condition

The literature shows several expressions of , e.g., (7), as in [10,11,12], but also other expressions for time-dependent fields (see, e.g., [3] and [9] (§ 2.16.1)). In other approaches, the term is expressed through the divergence of a (Maxwell) stress tensor to view the stress as the sum of a mechanical stress, , and an electromagnetic stress, [10,13], with the validity of the expression for being based on linear constitutive equations for and . Additionally, it is satisfactory, in relation to the generality, that the symmetry condition (14) is common to the known approaches in deformable electromagnetic bodies. Finally, we observe that

Accordingly, Equation (13) also implies that

3. Balance of Energy and Second Law of Thermodynamics

According to [9] (§ 2.16.1), electromagnetic power is assumed to be expressed as

Let be the specific energy density complementary to the kinetic one. Hence, we state the balance of energy in the form

where r is the heat supply and is the heat flux vector. Observe that

where is the velocity gradient, . Using the Reynolds’ transport relation, we find that

Consequently, in light of the equation of motion (6), we obtain

Let be the specific entropy density and the absolute temperature. The balance of entropy is expressed in the form

where s is the entropy supply, the (rate of) entropy production, and the entropy flux. Then, the local balance equation follows:

It is assumed that .

We denote the thermodynamic process by the set of functions, on , entering the balance equations. The statement of the second law is expressed through the following.

- The postulate of the second law. The admissible thermodynamic processes are those satisfying the balance equations and the inequality

Hereafter, Equation (17) is referred to as the CD (Clausius–Duhem) inequality.

Both and in (17) are taken to be unknown; they have to be determined so that the CD inequality holds for the model under consideration. The unknown character of traces back to Müller [14] while that of is established in [9] (§ 2.6).

It is customary to split the unknown flux in the form

and to regard as the extra-entropy flux. Upon the substitution into (17) of and from (16), we obtain

Hereafter, it is understood that . To describe thermodynamic processes, it is convenient to view and as independent variables. Since and , then we consider the free energy

Hence, by (18), the CD inequality takes the form

Admissible thermodynamic processes are required to satisfy the CD inequality (19) and the balance equations and then also the symmetry condition (14).

As is apparent, there is a dual behaviour for the pairs and and and . Accordingly, to save writing, we hereafter restrict attention to magnetic materials and formally let . The power is a mathematical analog to and does not affect the properties related to the symmetry condition (14). Hence for formal simplicity hereafter we let .

Remark 1.

The postulate (17) of the second law involves the (absolute) temperature as a primitive quantity. Sometimes, this choice is regarded as the indication that the postulate is valid near to equilibrium. As commented upon, e.g., in [15] (sec. 4), a way out of this approximation might be the use of the (internal) energy density as a primitive quantity and then letting the temperature be given by a constitutive function. This might imply constitutive consequences on the other function, depending on the assumption for the non-equilibrium temperature (see also [16]).

4. Lagrangian and Eulerian Fields Versus the Symmetry Condition

The velocity gradient is split into the stretching and the spin , so that . To describe the dynamics of heat-conducting magnetic solids, we let

be the set of variables, and hence, we take and to be given by constitutive functions of . We assume that and are continuous functions while is continuously differentiable. The electric field need not be zero in view of Maxwell’s Equation (4); yet, we let the constitutive properties of the magnetic solid be unaffected by . The mass density is related to the referential mass density by , .

We compute the time derivative and substitute it in (19) to find

In view of (4), the time derivative can be given arbitrary values, provided that takes appropriate values, without affecting the remaining terms of (20). The linearity and arbitrariness of , and imply that

Notice that and then

Furthermore, since

then

Hence, Equation (20) takes the form

where the dots stand for the remaining terms, none of which involve . The linearity and arbitrariness of implies that

Hence, Equation (20) simplifies to

We divide Equation (24) by and notice that

Hence, we can write

where

can be viewed as the variational derivative of with respect to . Thus, we let

Though might depend on , we restrict the generality and let

Hence, upon multiplying by , the remaining part of Equation (25) can be written as

The reduced CD inequality (26) is investigated in § Section 5 within a slightly different scheme. We now go back to the symmetry condition (23) along with that in (14).

4.1. Stress Tensor and Symmetry Conditions

Two symmetry conditions are required, namely (23) by thermodynamics and (14) by the balance of angular momentum, so that we have

In the following, we make a term-by-term comparison between these two conditions.

As to , if both and are nonzero, then might have a joint dependence on and and hence on or . In both cases, need not be collinear to , and hence, a non-local dependence on might result in a couple density. By the obvious identity

we can identify the skew-symmetric tensor in (27) with the skew part of , namely

As to , a comparison with the corresponding term in (27) leads to the requirement

In light of (22), this constraint amounts to

In particular, we observe that if depends on , then

Likewise, if depends on through ; then,

whence

In both cases, the comparison of the symmetry conditions in (27) leads to

a condition which is satisfied only if (and then ) is collinear to , such as if depends on through .

We can also consider the alternative constraint that is obtained by applying the symmetry condition (15) instead of (14), namely

In light of (22), this constraint amounts to

which is equivalent to (29). All previous considerations apply in this case too.

We now summarize the main points of this section; for definiteness, we identify with the skew parts of . By (27), the second law of thermodynamics and the balance of linear momentum imply that

If is collinear to , i.e., , then , and hence, by (32), . In this event, Equation (31) results in the condition

for the free energy .

Instead, assume that the physical properties of the material result in

This occurs if the material is magnetically anisotropic, which is the case for the vast majority of magnetic materials. Hence,

so that by (32) we have and, correspondingly, . Furthermore,

By thermodynamics, it is , and hence, by (33), it follows that

It is then required that depends jointly on and in a proper way.

4.2. Lagrangian Fields Versus the Symmetry Condition

There are infinitely many dependencies of the free energy on and , consistent with (34). To simplify the search for combinations, we restrict our attention to Lagrangian fields, which are Euclidean-invariant (see Appendix B).

First, we consider the condition (stronger than (34))

and assume depends on a vector, , whence

For any dependence of on , this condition holds if and only if

A solution to (35) and then to (29) is

Note that denotes the usual representation of the magnetic field in the reference configuration [17]. More general solutions to (35) are for any function, f, of . This follows from the observation that (see [9] (§ A.3))

Really, further solutions arise if we take into account the most general constraint (29) on the joint dependence on and through . Condition (29), in components, can be written in the form

whence

Hence, the symmetry conditions (27) require that we look for solutions to (36). While we have shown that satisfies (35) and hence also (36), the direct check and use of (see, e.g., [9] (§ 1.2.2))

show that , as well as , satisfies the condition (36).

We therefore conclude the following:

Proposition 1.

In the next Section 5, we show the physical relevance of the field and, especially, of .

4.3. Electromagnetic Interactions in Micropolar Media

The symmetry condition (14) does not hold in micropolar media. As is the case, e.g., for liquid crystals and nanofluids, let the continuum be endowed with an orientational momentum, , per unit mass, which models a distribution of particles with their own spin. Accordingly, the balance equations for mass and linear momentum hold unchanged, i.e.,

Instead, the balance of angular momentum needs a generalization due to the emergence of . For any sub-region, , we let the angular momentum be

and assume the balance equation in the form

Since

using the equation of motion, we find that

Equation (37) governs the evolution of the orientational momentum ; the right-hand side is the effective torque per unit volume due to mechanical and electromagnetic fields. Consequently, the symmetry condition (14) is found for continua free from orientational momentum ().

Finally, the set of balance equations is completed by assuming the total energy density in the form

where is the angular velocity of the micropolar particles immersed in the continuum (see, e.g., [9] (sec. 10.2).

5. Constitutive Models with the Field

The arguments around the symmetry conditions (27) indicate the field as a convenient vector field to represent the magnetic field in deformable bodies. We then investigate models based on the set

of variables and the constitutive functions and . For simplicity, the dependence on is ignored here while and are considered rather than and . Moreover, the CD inequality is then considered in the form

the extra-entropy flux is taken to be zero in accordance with the absence of among the variables. Since and , then

We compute and substitute in (38). Replacing the expression of , , and , upon some rearrangements, we obtain

where

The linearity and arbitrariness of imply that

where .

The result (41) for shows that the simple use of as a variable, instead of , provides from scratch the symmetry condition arising from the balance of angular momentum. Furthermore, arises as the magnetization conjugate to the magnetic field . Further properties emphasize the conceptual relevance of the fields and (see Appendix B).

The reduced dissipation Equation (42) determines the constitutive equation of in terms of and while ; .

By (40), we have . For definiteness, we restrict the possible dependences and cross-coupling properties by letting

Hence, Equation (42) splits into two thermodynamic restrictions on the constitutive relations,

5.1. Solutions to the Thermodynamic Restriction (43)

We now regard (43) as an algebraic equation in the unknown .

We notice that, by a representation formula (see [9] (§ A.1.3)), for any pair of nonzero tensors, and , we can write the identity

where is the four-dimensional unit tensor, . Indeed, is the longitudinal part of , with respect to , and is the transverse (or orthogonal) part. Furthermore, for any tensor, ,

and then is orthogonal to . If is known, say, , then a general representation of is

If, furthermore, , then both and are required to be symmetric.

Back to (43), we apply (46) with the identifications to obtain

Based on the symmetry of , we can select

and then obtain

The term represents a dissipative effect in that, by (47), it follows that

identically for any magnetic field, . The other quadratic terms in are non-dissipative and thermodynamically consistent. Accordingly, represents non-dissipative solids, in which case (see [9] (§ 12.6)),

The symmetric tensor Equation (47) can be given an invariant form. In this regard, we consider the time derivative of the Cauchy–Green tensor ; using the relation , we obtain

Hence, by the Green–Lagrange strain tensor , we can write

Replacing in (47), we have

Hence, left multiplication by and right multiplication by give

where . It is of interest that the form (48) is invariant under Euclidean transformations in that so are and .

5.2. Solutions to the Thermodynamic Restriction (44)

Equation (44) can be written in the form

Assume that and solves in the unknown . Using the analog of Equation (45) for vectors, we can write in the form

where the vector is allowed to depend on . In light of (49), we have

consequently, is collinear to within the transverse vector associated with . Infinitely, many forms of (50) occur depending on the chosen functions, and . Having in mind the well-known Maxwell–Cattaneo equation and Fourier’s law [18], we let

Hence, (50) takes the form

Next, we let ; in the particular case that , it follows that

Equation (51) has the form of the Cattaneo–Maxwell equation with the relaxation time

and then is required. If , then we find that

which is just Fourier’s law with the heat conductivity

Hence, implies that .

6. Models for Positive and Negative Magnetostriction

Especially in connection with magnetoelastic sensors and actuators, it is of interest to investigate the modeling of strain produced by a given stress (or stress impedance). As shown in the literature (e.g., [19,20,21] and refs therein), several effects connected with non-linearity, hysteresis, frequency dependence, and positive–negative magnetostriction occur. Here, we illustrate two aspects related to the sign of a magnetostriction. First, we show that different signs of a magnetostriction are obtained depending on the variable chosen to represent the interaction between deformation and the magnetic field.

If depends on , then it follows from the previous section that

Assume that depends on through the quadratic scalar where is a symmetric fourth-order (elasticity) tensor. Hence, we can write

Apart from the dissipative term , we conclude that the effective stress acting on the body is the sum .

Instead, we might take as dependent on . Since

then substitution into

yields the thermodynamic inequality in the form

with the dots representing terms independent of and . Hence, it follows that

While

the effective stress turns out to be

instead of . The difference is even more evident if we consider one-dimensional settings where the two stresses would be

In the first case, we recognize a positive magnetostriction, namely an additional term producing deformation due to the magnetic field; in the second one, there is a negative magnetostriction.

There are experimental data showing that a positive or negative magnetostriction in a given material depends on the value of the stress itself. This property is referred to as stress-impedance effect and has been observed experimentally in Co Fe Ni Mo B Si alloy [22] and Mn Zn Fe O ferrite [23]. In this connection, attention has been addressed to the Villari effect whereby the flux , for a given magnetic field, , depends on the applied stress in a non-monotonic way [24,25,26].

To clarify this point, we mention that, based on the data for NO Fe Si steel [24,25], we determined a thermodynamically-consistent one-dimensional model [27] where is given the form

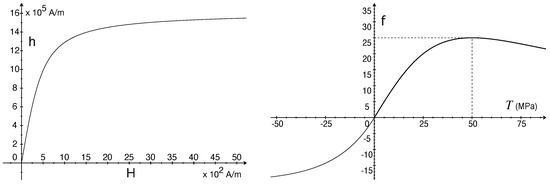

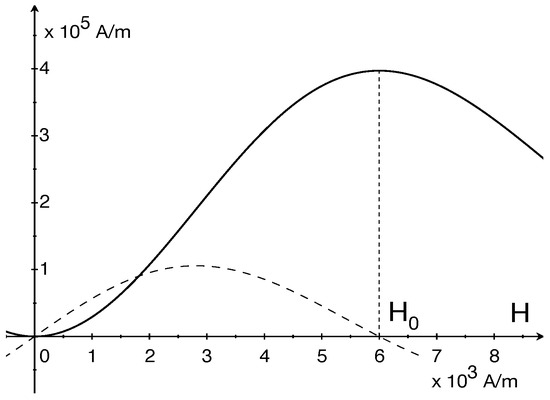

and are positive functions of the applied magnetic field , with , and is a function of the stress T that has a maximum at , with being referred to as a Villari point [28]; the functions , and are plotted in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Plots of (left) and with MPa (right).

Figure 2.

Plots of , with A/m (solid line) and (dashed line).

Since , then by the integration of (53), we have

where is the primitive of . The thermodynamic condition

results in

The relative deformation (impedance) induced by the magnetic field is

Since as and as , then the sign of changes across . Equation (54) shows that materials with a non-monotonic function, , (such as NO Fe-Si steel) can exhibit a change in sign of the magnetostrictive effect that depends on the applied stress.

7. Conclusions

The paper investigates some formulations of constitutive equations for electromagnetic solids subject to the constraint (14) that follows from the balance of angular momentum. Starting with a generic dependence of the free energy on the deformation gradient and the magnetic field , it is shown in Section 5 that the two symmetry constraints (27), arising from thermodynamics and balance of angular momentum, lead to the condition (29) and indicate the dependence on the field

as the appropriate variable identically satisfying the two symmetry constraints. It then follows as a thermodynamic requirement that

is the magnetization field conjugated to . Incidentally, and are the magnetic field and the magnetization field often involved within modeling through Lagrangian fields. It is also shown that and are Euclidean invariants, which makes any function of and/or identically Euclidean-invariant. The same properties hold for the electric field and the polarization .

The symmetry condition (29) is found to hold even for the field which is also Eulerian-invariant. However, the field seems to be preferable in the literature in relation to its meaning as a Lagrangian field. Section 6 shows that produces a positive magnetostriction, produces a negative magnetostriction.

No recourse is made to the splitting of the stress tensor as the sum of the mechanical stress and the magnetic (or electric) stress. In the balance equation, or symmetry condition,

the stress tensor is the stress within the body which has to balance the skew part of . This avoids non-uniqueness problems and questions the appropriate form of the magnetic stress.

Among the results obtained, we mention that, for elastic solids, it follows from thermodynamics that the stress tensor has the form

where the free energy is a function of the temperature , the strain , and the magnetic field . Further, upon the use of a representation formula for vectors and tensors, the thermodynamic reduced conditions are investigated to determine the dissipative stress and the rate . It is of interest that there is the allowed dependence on the stretching in the form (47), namely

where and are functions of the temperature and the strain. The analogous application of the representation formula for the terms involving the heat flux results in a family of evolution equations among which the Maxwell–Cattaneo equation is obtained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing, editing: A.M. and C.G. All authors have contributed equally and substantially to the work reported. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to this work was developed under the auspices of Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica–Gruppo Nazionale di Fisica Matematica.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Some Notes on Vector and Tensor Algebra

We consider the right-handed orthonormal basis and define

By definition, we have

and . Also,

and . Furthermore, if two indices are equal. Hence, we obtain the definition (10) of the alternating symbol .

Consider the inner product of two vectors, and , and notice that

Hence, we have

By viewing as the mixed product of , we can write

Now, is zero if . If , then is a linear combination of and :

To determine , we observe that

Likewise,

Hence, it follows that

Consequently,

For any tensor, , the component

involves only the skew part of in that

Hence,

Accordingly, the definition

determines in terms of . Now,

and the divergence, for any i, results in

and (11) follows.

Appendix B. Lagrangian Fields and Euclidean Invariance

Though there is no particular attention to the symmetry requirement (14), the description of electromagnetic fields in the reference configurations (called Lagrangian fields) is found to allow a more transparent formulation of the constitutive equations (see, e.g., [4,29,30,31]). The Lagrangian counterparts of and are just

as determined above.

Two frames of reference, and are related by a Euclidean transformation if the position vectors of a point, and , are connected by the relation

where is a rotation tensor; .

Since and are independent of the position, differentiation with respect to gives

Under a change in frame, the current position of a point changes according to (A2) while the reference position , as a label of the point, is unchanged. Hence, we make the identifications

Hence, Equation (A3) results in the transformation property

Consequently, , as well as , and is invariant in that

Both and are assumed to change as vectors under a Euclidean transformation, namely

Consequently, it follows that

Indeed, we realize that, for any vector, , the invariance holds for all quantities of the form and . In this sense, we mention that sometimes, in the literature [17], the field is also applied instead of .

The same holds for the electric field and the polarization . Thus, and are Euclidean-invariant. Hence, a dependence on and or (as well as or ) makes a function identically invariant under Euclidean transformations [32].

References

- Fano, R.M.; Chu, L.J.; Adler, R.B. Electromagnetic Fields, Energy, and Forces; MIT Press: Cambridge MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Maugin, G.A. Continuum Mechanics of Electromagnetic Solids; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pao, Y.-H.; Hutter, K. Electrodynamics for moving elastic solids and viscous fluids. Proc. IEEE 1975, 63, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfmann, L.; Ogden, R.W. The nonlinear theory of magnetoelasticity and the role of the Maxwell stress: A review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2023, 479, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaldin, N.A. A beginner’s guide to the modern theory of polarization. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 195, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Electrodynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtin, M.E.; Fried, E.; Anand, L. The Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Continua; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kovetz, A. Electromagnetic Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morro, A.; Giorgi, C. Mathematical Methods of Continuum Physics; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, R.; Dorfmann, A.; Ogden, R.W. On electric body forces and Maxwell stresses in nonlinearly electroelastic solids. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2009, 47, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, R.; Rajagopal, K.R. On a new class of electroelastic bodies. I. Proc. R. Soc. A 2013, 469, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfmann, A.; Ogden, R.W. Nonlinear magnetoelastic deformations. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Math. 2004, 57, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Hossain, M.; Steinmann, P. Nonlinear magneto-viscoelasticity of transversally isotropic magnetoactive polymers. Proc. R. Soc. A 2014, 470, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, I. On the entropy inequality. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1967, 26, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Vázquez, J.; Jou, D. Temperature in non-equilibrium states: A review of open problems and current proposals. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2003, 66, 1937–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujrati, P.D. Irreversibility, dissipation, and its measure. Symmetry 2025, 17, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfmann, L.; Ogden, R.W. Hard-magnetic soft magnetoelastic materials: Energy considerations. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2024, 294, 112789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, B. Heat Waves; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gazda, P.; Nowicki, M.; Szewczyk, R. Comparison of stress-impedance effect in amorphous ribbons with positive and negative magnetostriction. Materials 2019, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienkowski, A. Magnetoelastic Villari effect in Mn-Zn ferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2000, 215, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, F.; Fox, M.A. A review on piezoelectric, magnetostrictive, and magnetoelectric materials and device technologies for energy harvesting applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1700743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazda, P.; Nowicki, M. Giant stress-impedance effect in CoFeNiNoBSi alloy in variation of applied magnetic field. Materials 2021, 14, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieńkowski, A.; Kulikowski, J. Effect of stresses on the magnetostriction of Ni-Zn(Co) ferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1991, 101, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, L.; Rekik, M.; Hubert, O. A multiscale model for magneto-elastic behaviour including hysteresis effects. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2014, 84, 1307–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, O. Multiscale magneto-elastic modeling of magnetic materials including isotropic second order stress effect. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 491, 165564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, R. Stress-induced anisotropy and stress dependence of saturation magnetostriction in the Jiles-Atherton-Sablik model of the magnetoelastic Villari effect. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2016, 61, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.; Morro, A. On the Modelling of Magneto-Mechanical Effects in Solids. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4750363 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Riesgo, G.; Elbaile, L.; Carrizo, J.; Crespo, R.D.; García, M.Á.; Torres, Y.; García, J.Á. Villari effect at low strain in magnetoactive materials. Materials 2020, 13, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfmann, L.; Ogden, R.W. Nonlinear electroelasticity: Material properties, continuum theory and applications. Proc. R. Soc. A 2017, 473, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Kari, L. Constitutive model of isotropic magneto-sensitive rubber with amplitude, frequency, magnetic and temperature dependence under a continuum mechanics basis. Polymers 2021, 13, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, M.; Hossain, M.; Steinmann, P. Numerical modeling of thermo-electro-viscoelasticity with field-dependent material parameters. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2018, 106, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.; Morro, A. Electrostriction and modelling of finitely deformable dielectrics. Acta Mech. 2024, 236, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).