Finite Element Parametric Study of Nailed Non-Cohesive Soil Slopes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

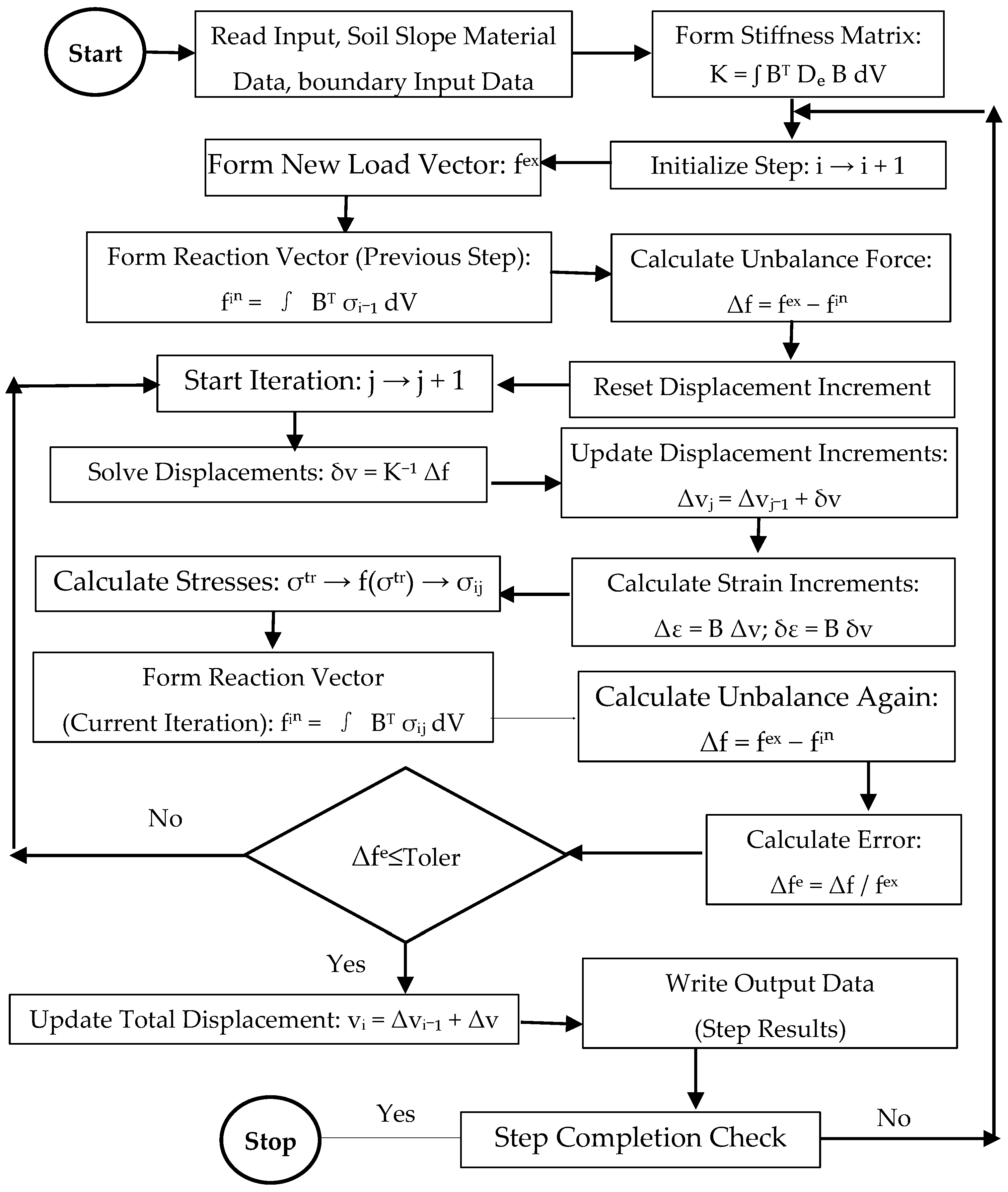

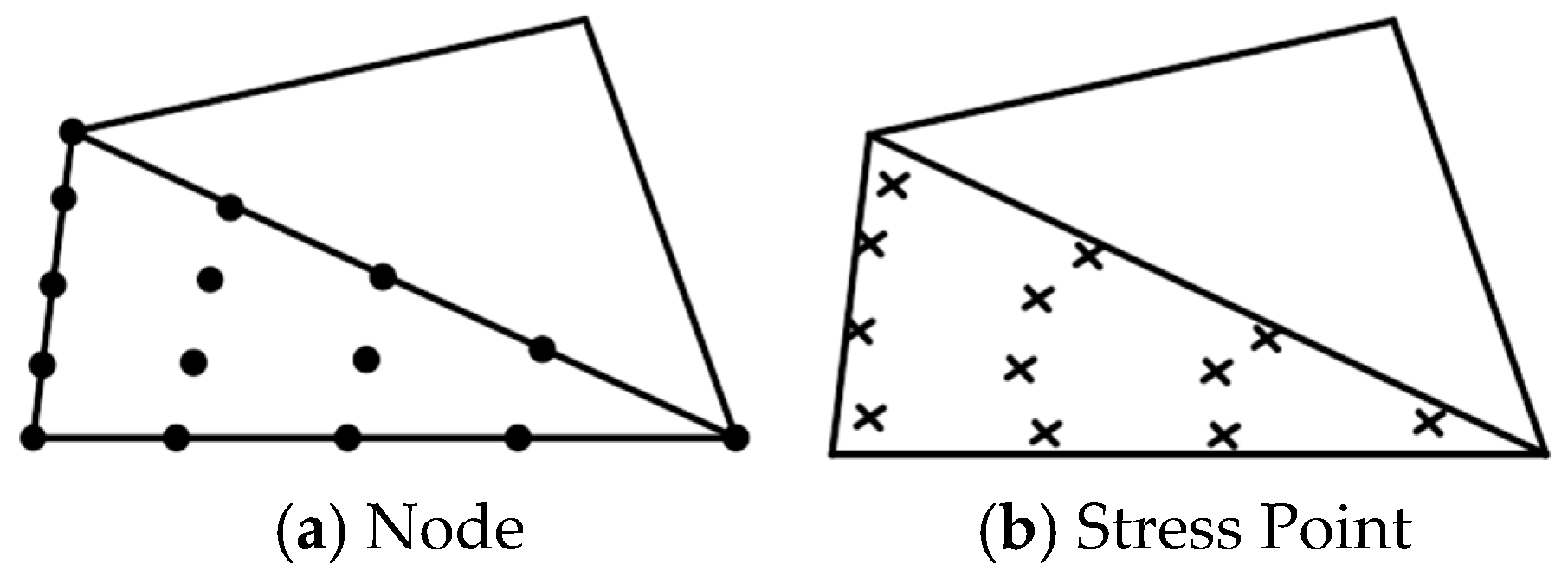

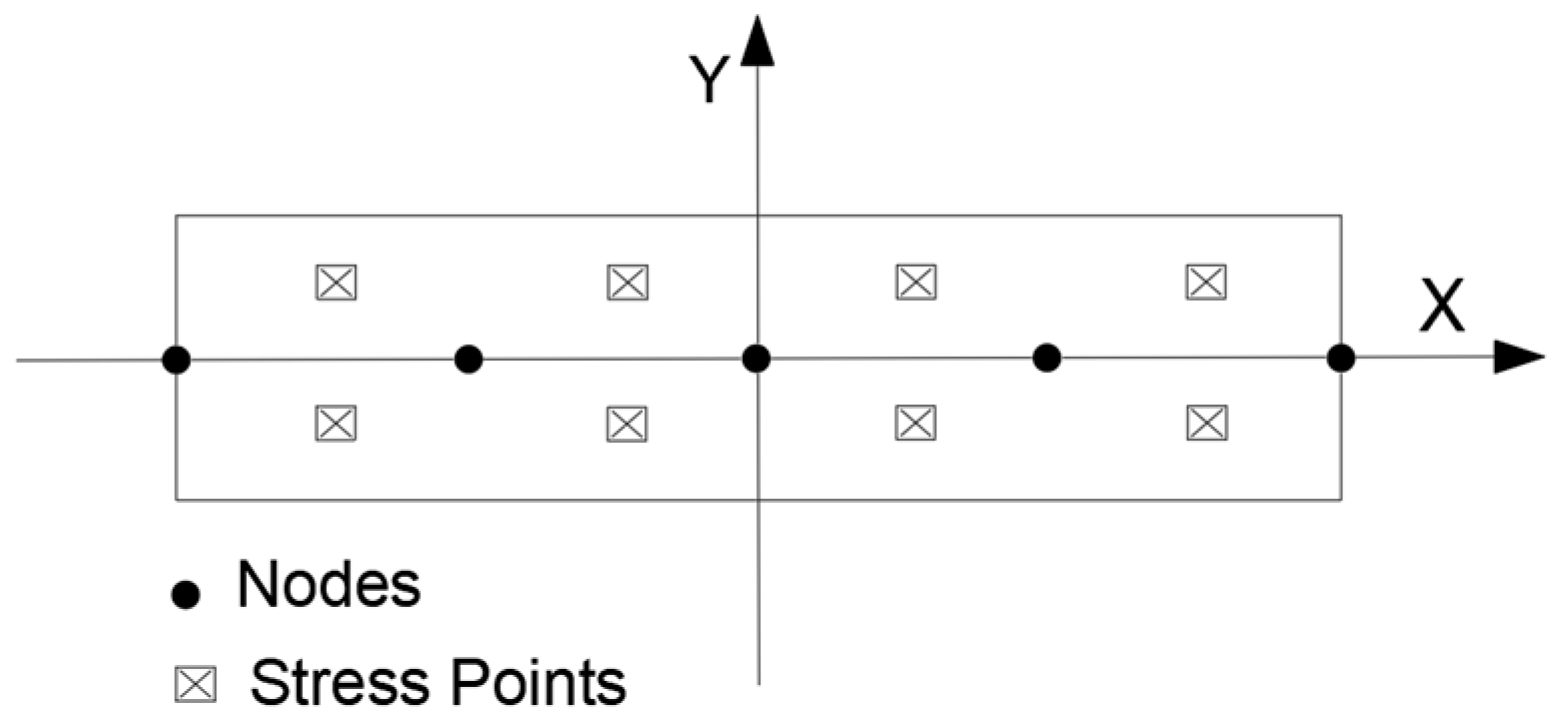

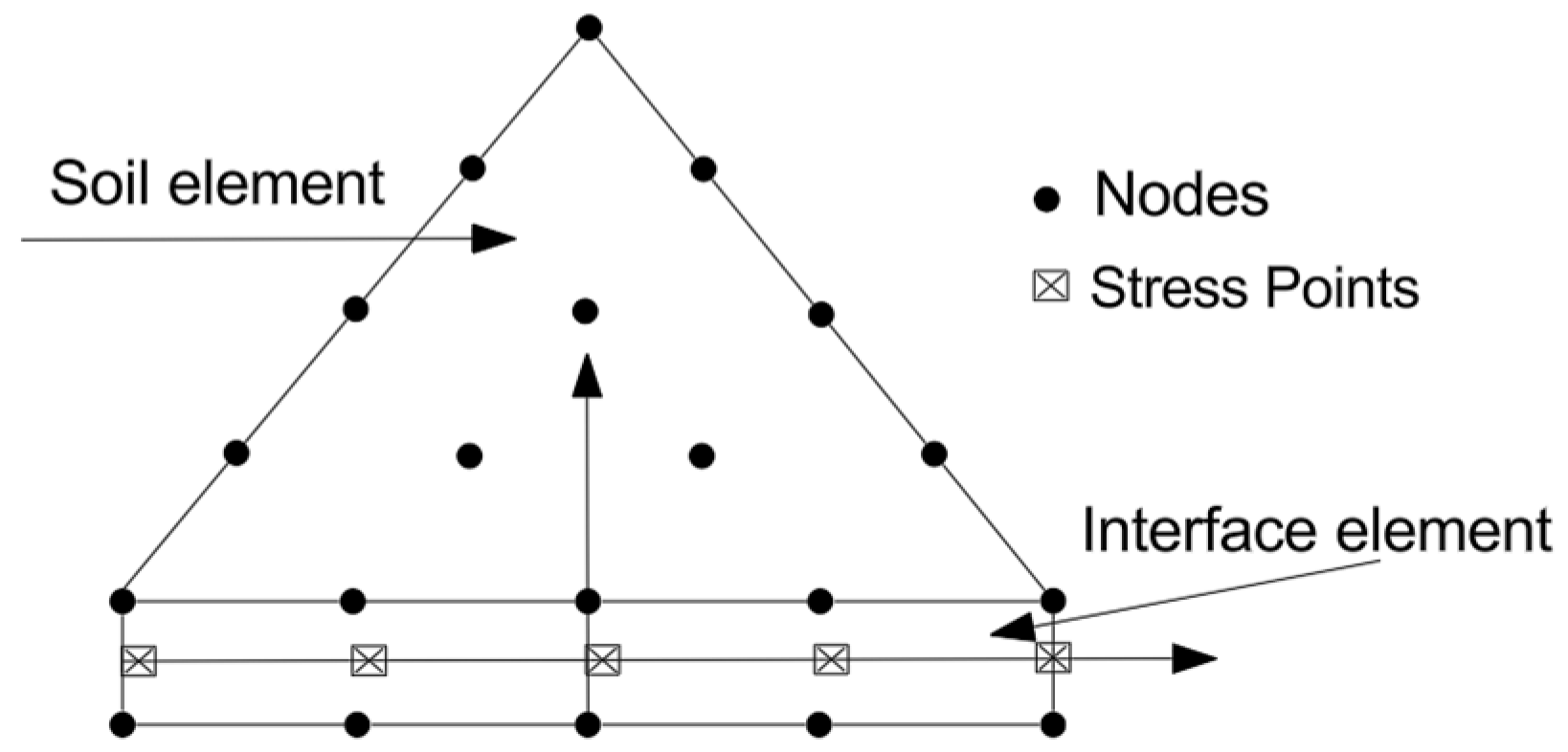

2.1. Material Models and Numerical Methods

2.2. Model Dimensions and Development

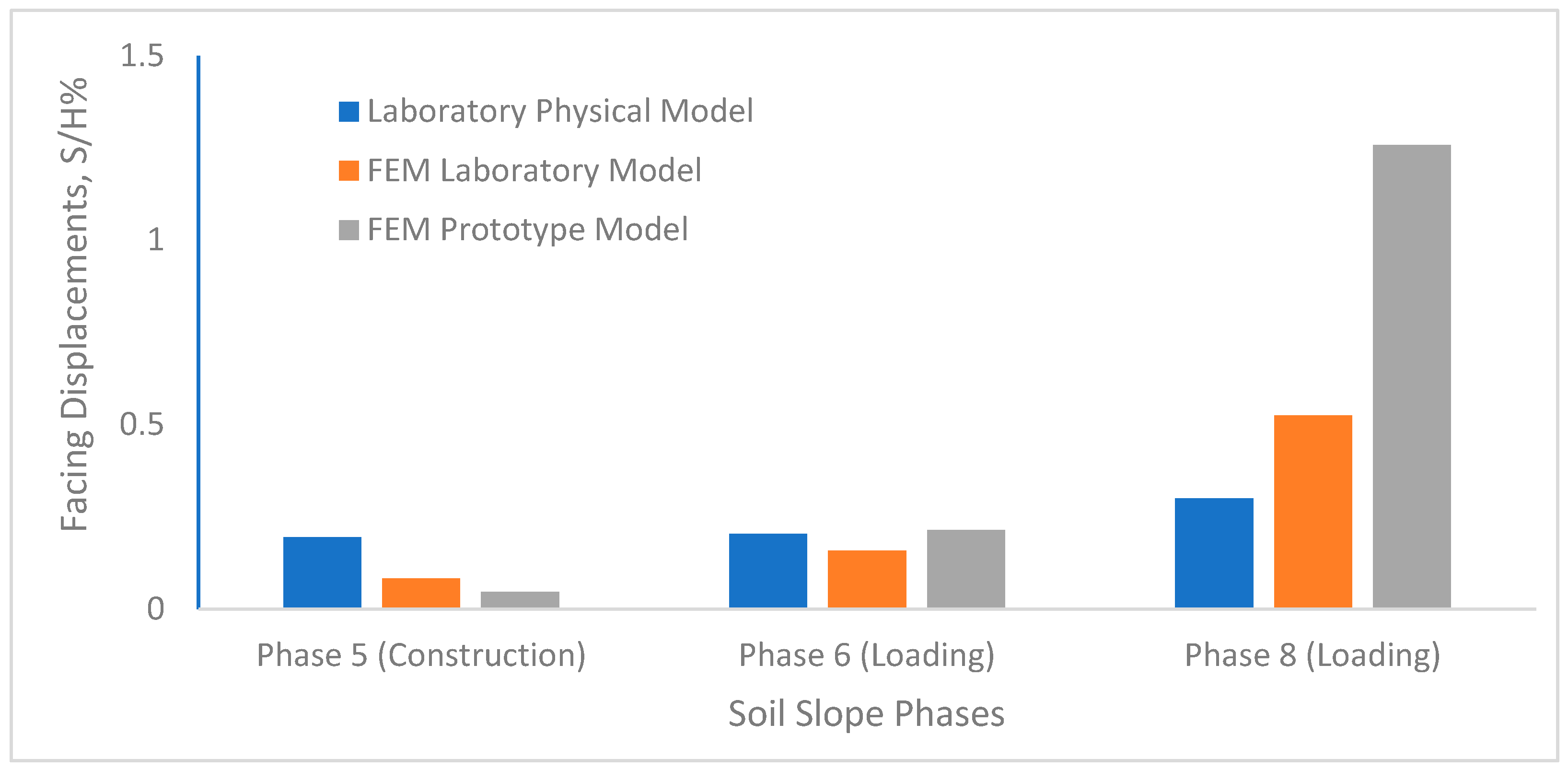

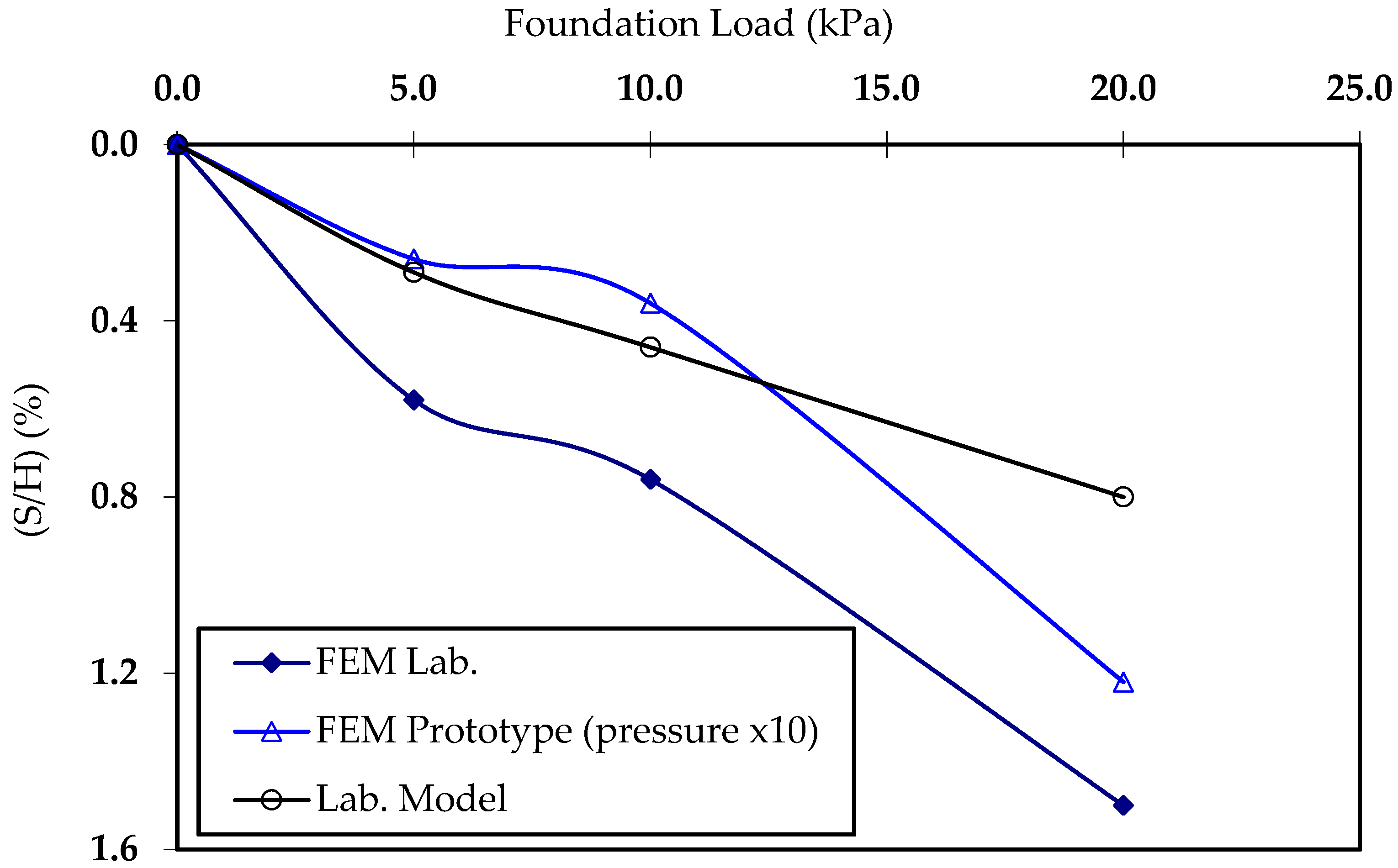

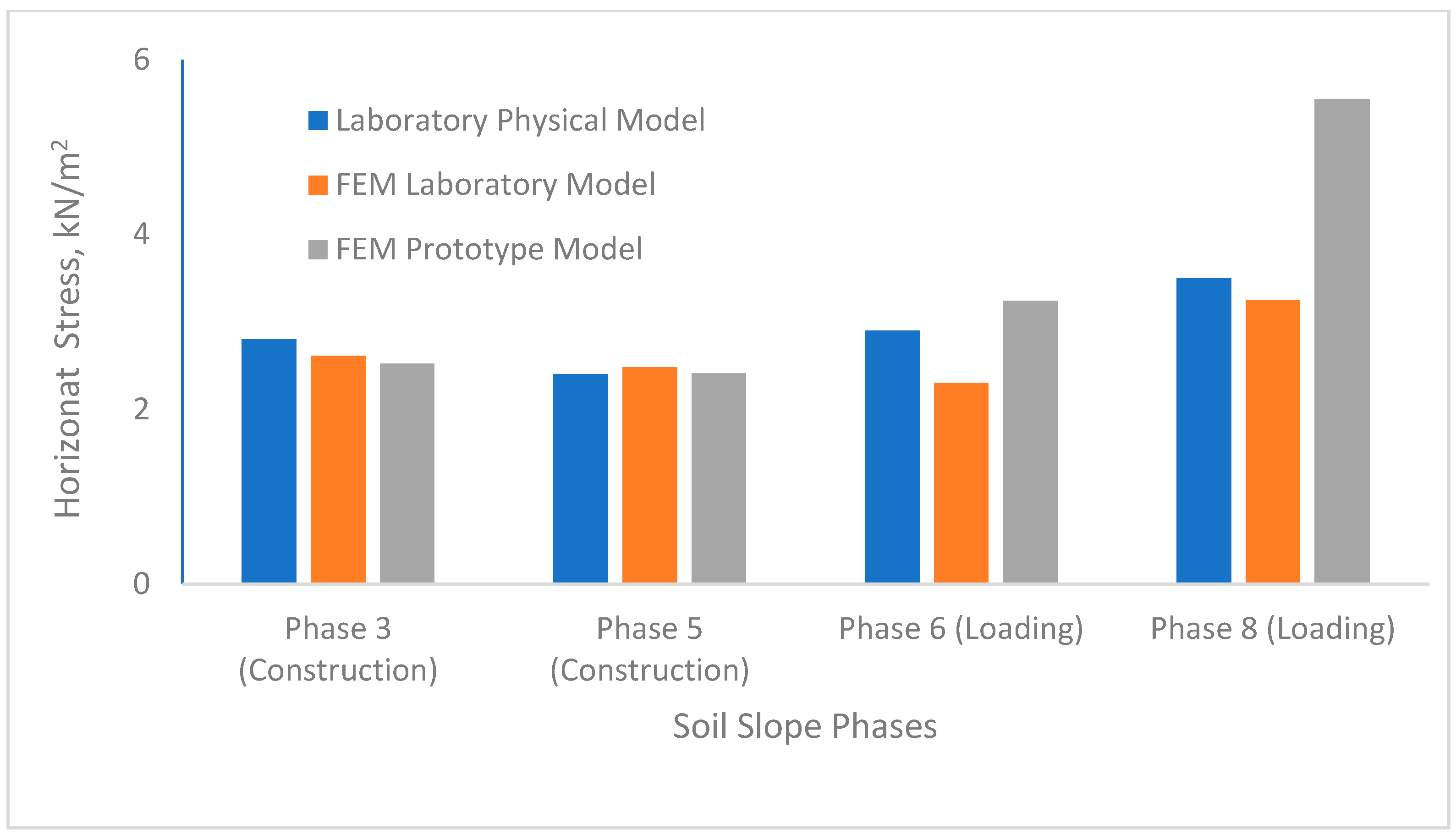

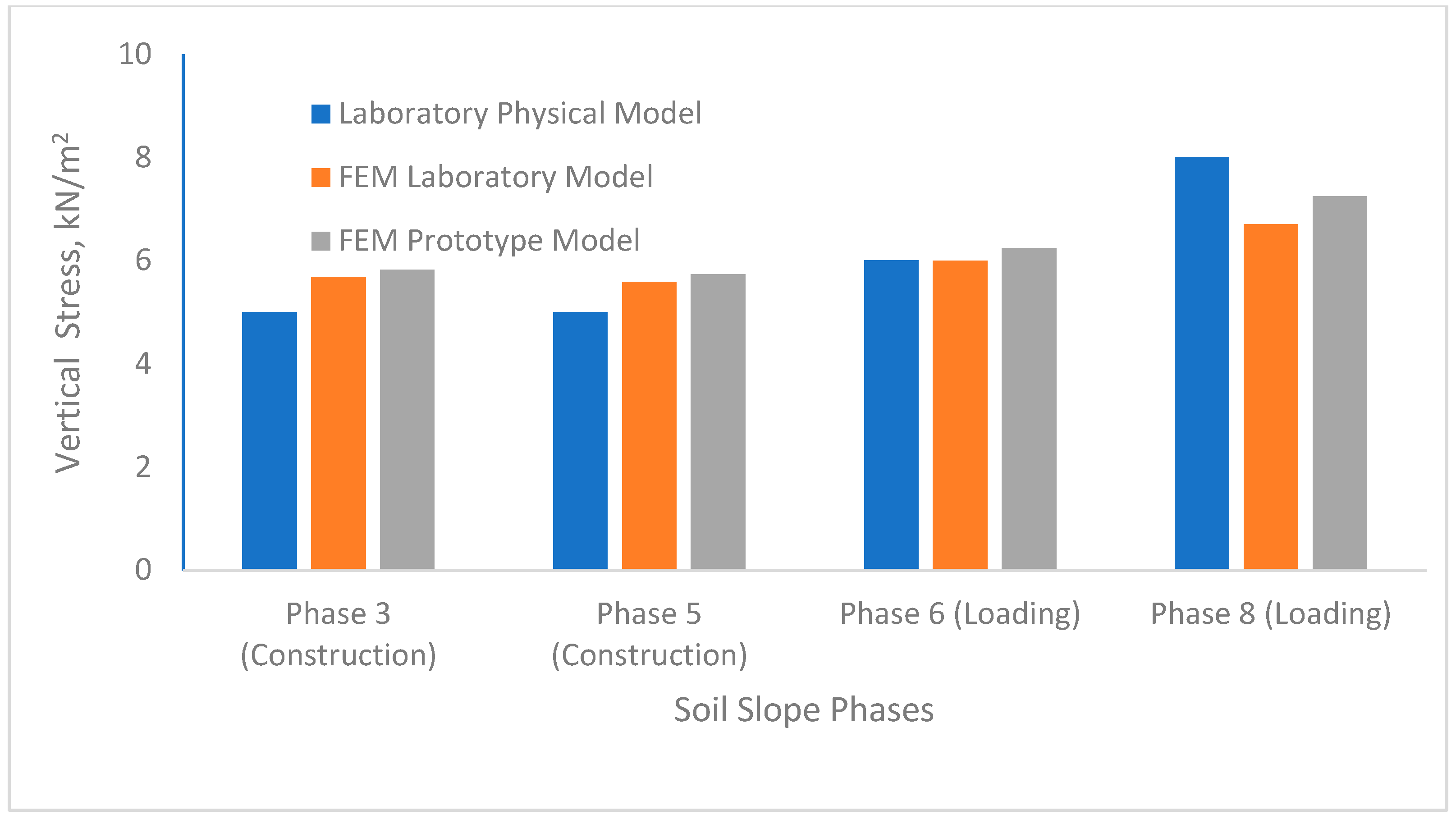

- Phases 1–5: The first excavation phase was to a depth of 140 mm, followed by the second excavation phase at 280 mm, the third at 420 mm, the fourth at 560 mm, and the fifth at 700 mm below the ground surface. Install the first, second, and third nail layers at depths of 70 mm, 350 mm, and 630 mm from the top ground surface.

- Phases 6–8: Foundation is positioned at the required location, applying foundation loads, self-weight included, to achieve footing loads (q) equal to 5 kN/m2 (phase 6), 10 kN/m2 (phase 7), and 20 kN/m2 (phase 8).

3. Reinforced Soil Slope Models: Parametric Study Results

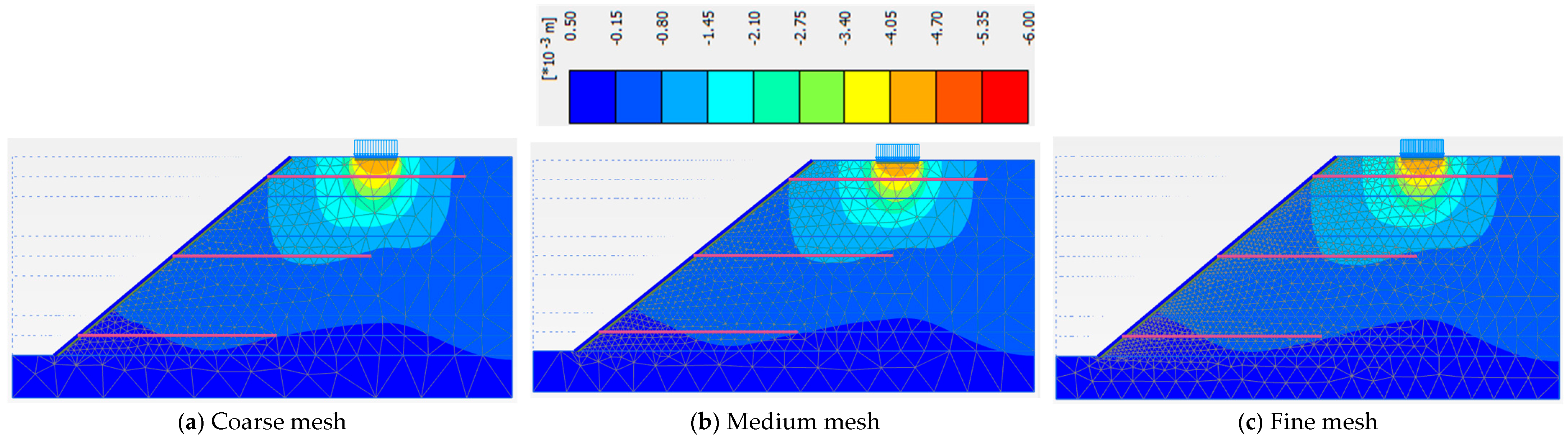

3.1. Domain Discretization and Mesh Sensitivity

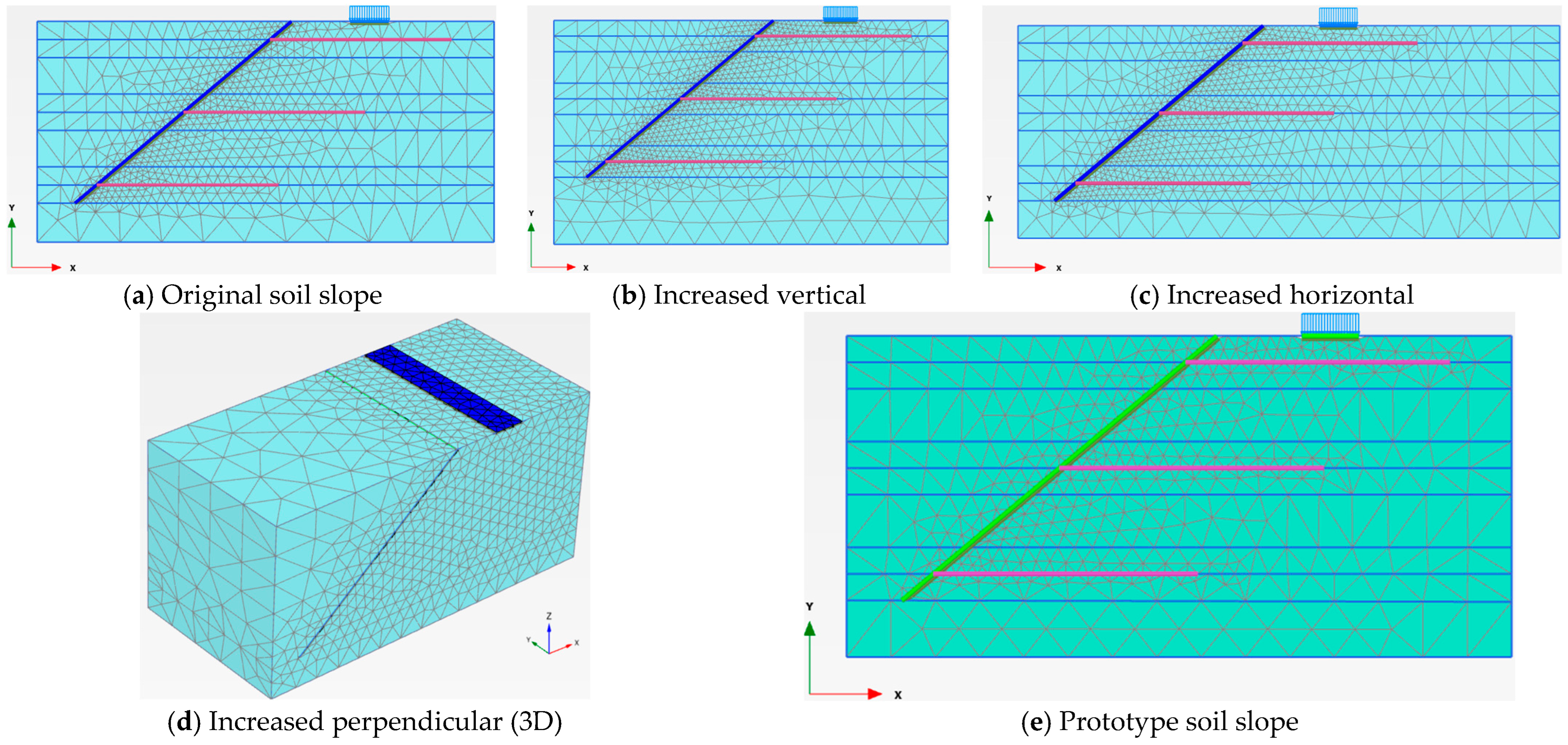

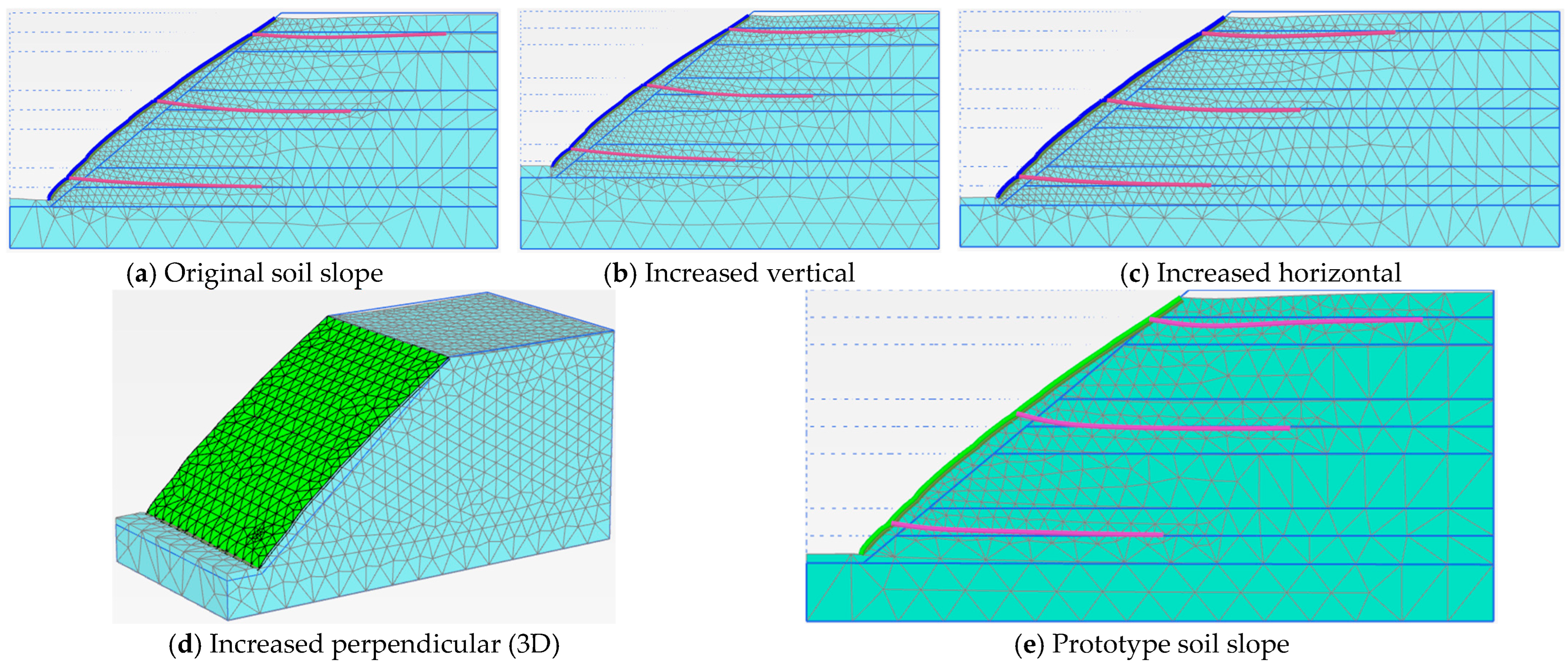

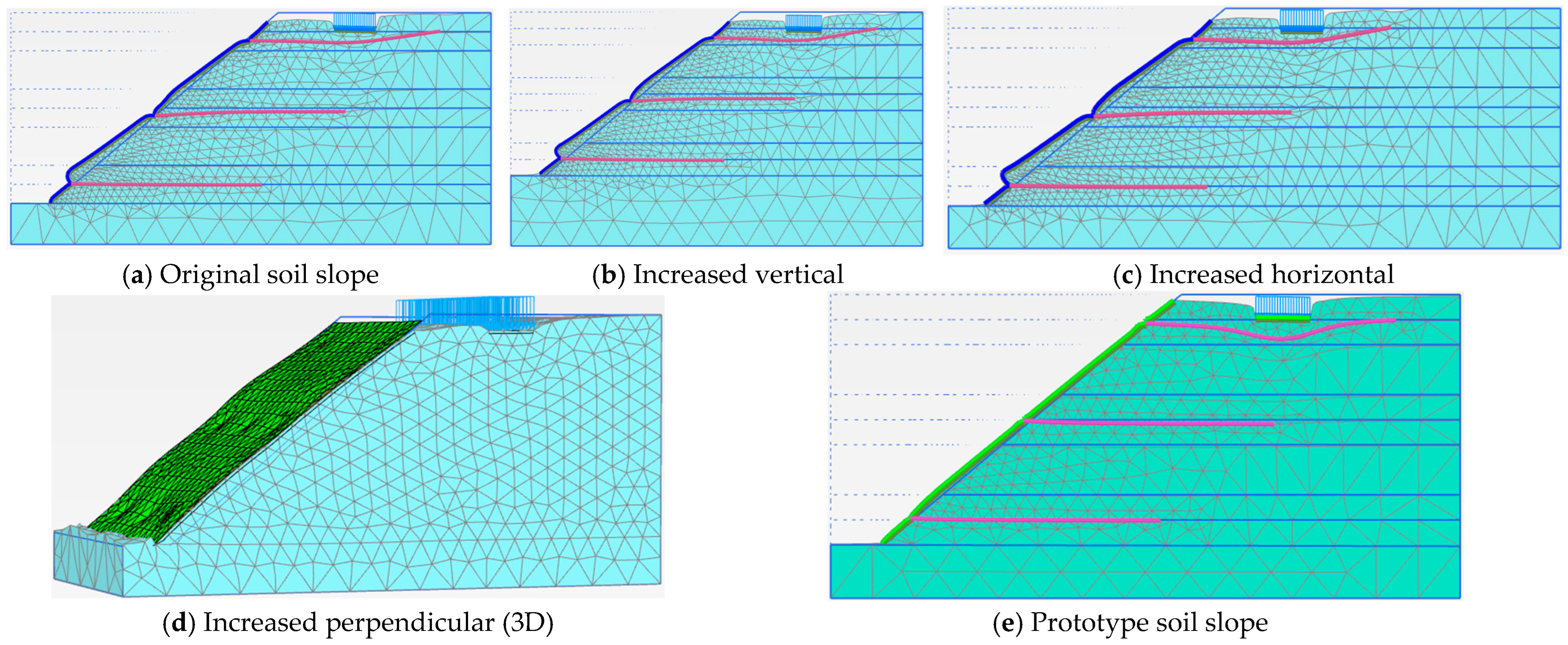

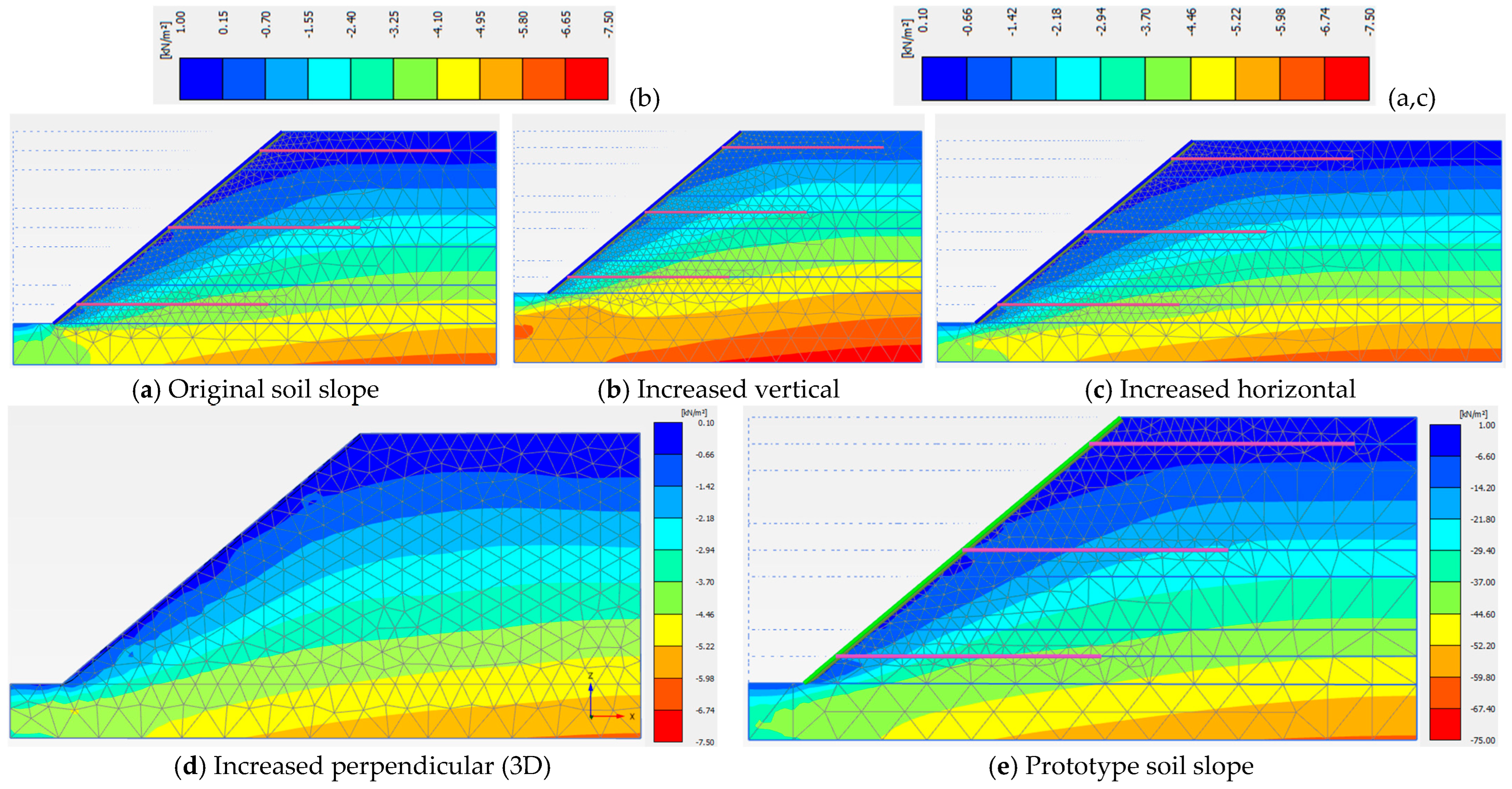

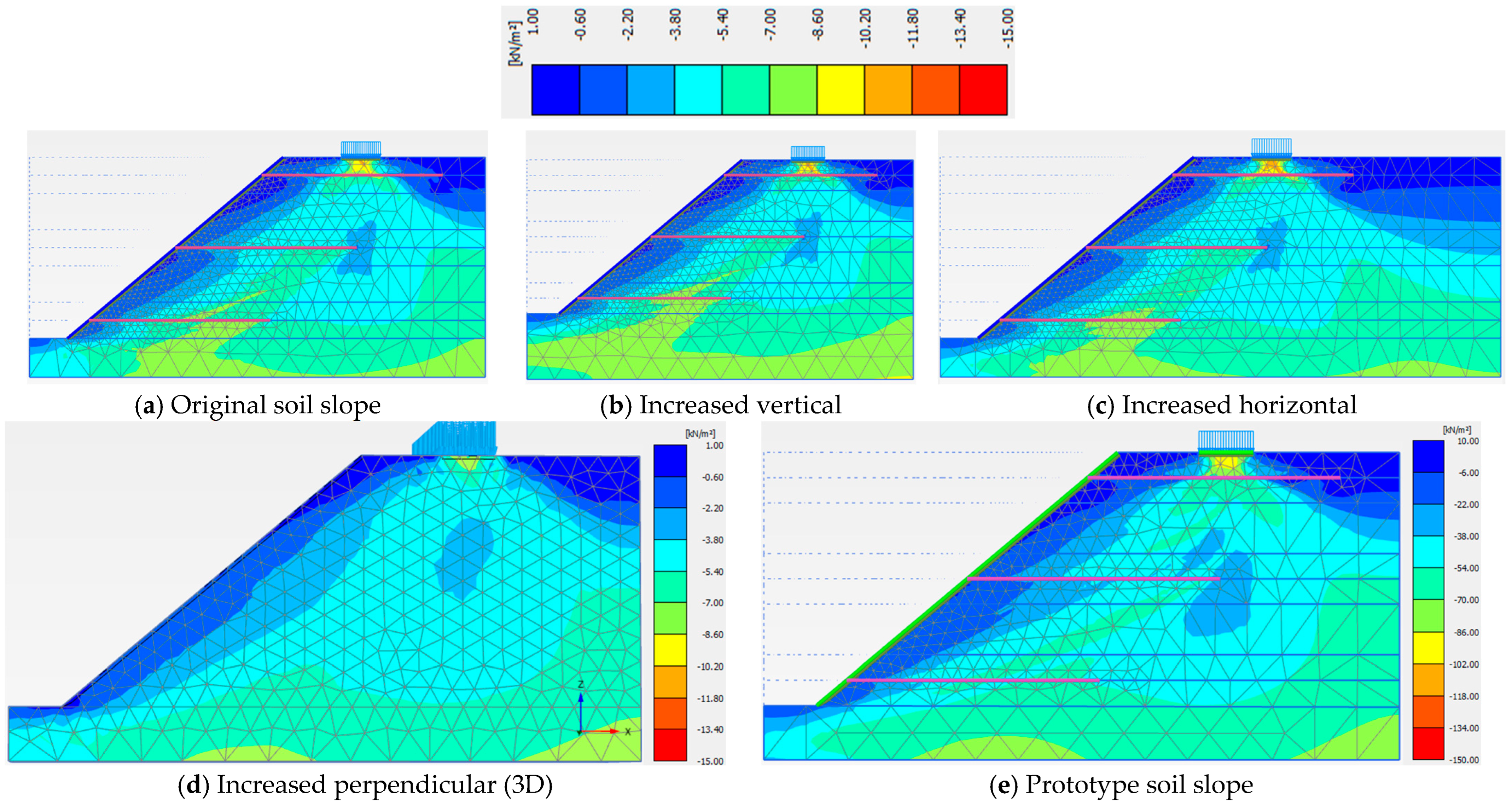

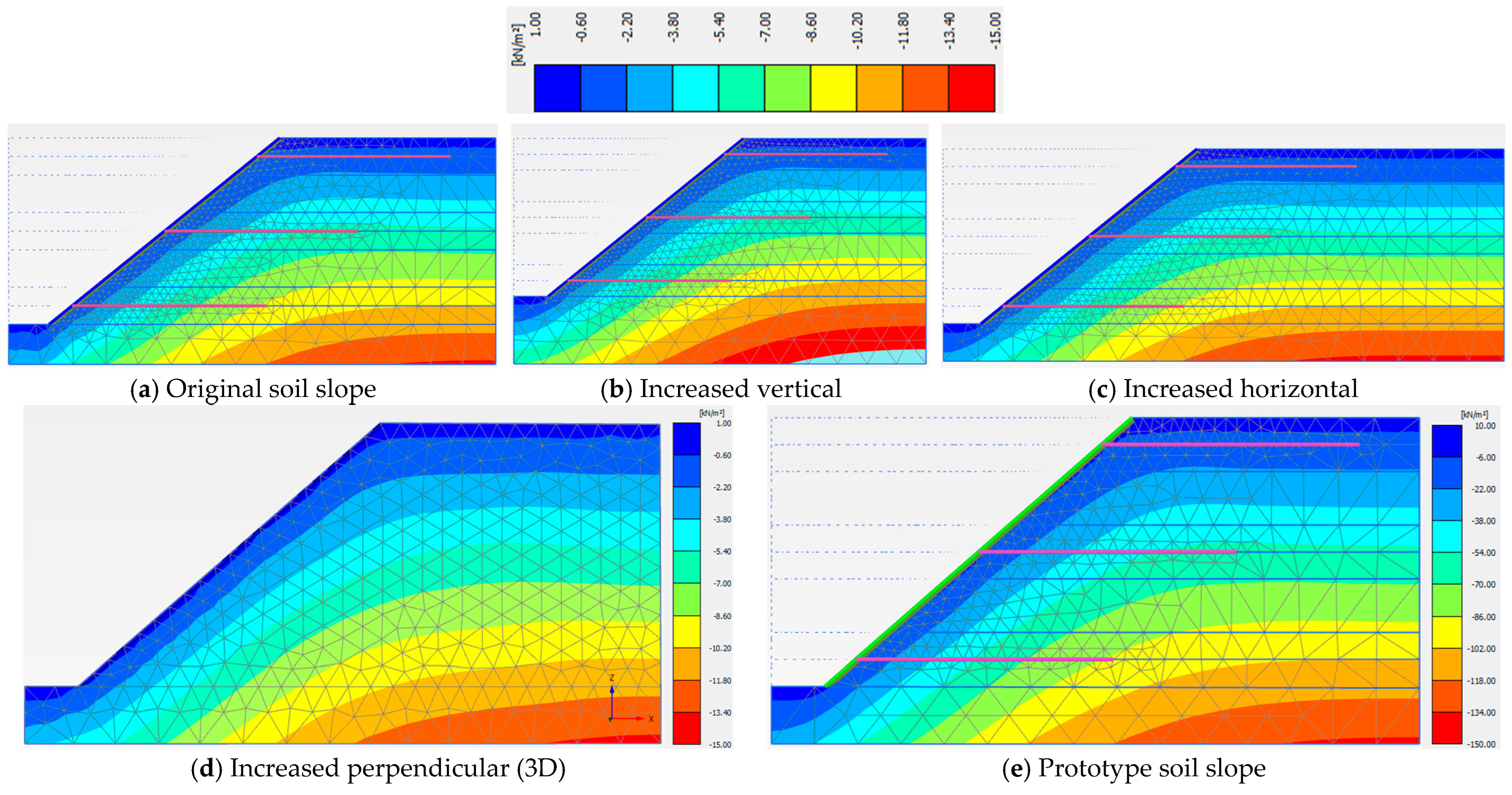

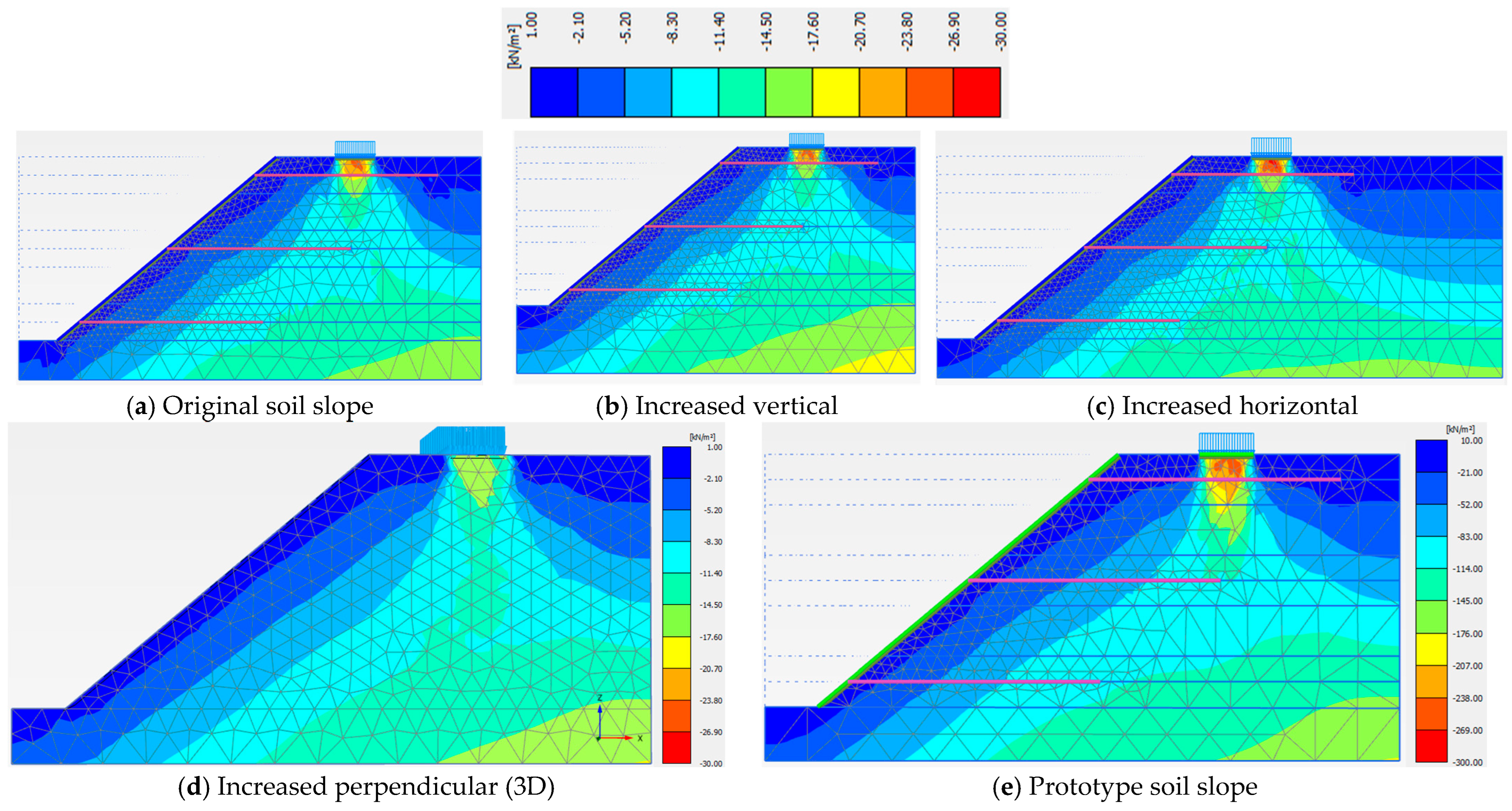

3.2. Model Dimensions

3.3. Slope Angles and Material Models

3.4. Nail Length Distribution Strategies in Slope Layers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FOS | Factor of Safety |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| HS | Hardening Soil |

References

- Panigrahi, R.K.; Dhiman, G. Design and Analysis of Soil Nailing Technique for Remediation of Landslides. Highw. Res. J. 2019, 10, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan, P.A.; Madhavan, M. Application of FEM and Artificial Intelligence Techniques (LRM, RFM, ANN) for Predicting the ultimate Bearing Capacity of Reinforced Soil foundation. Buildings 2024, 14, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaravel, V.; Dodagoudar, G.R. Finite Element Analysis of Reinforced Earth Retaining Structures: Material Models and Performance Assessment. Indian Geotech. J. 2024, 54, 2076–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.D.; Xu, K.; Tang, X.; Tham, L.G. Three-Dimensional Modeling of Spatial Reinforcement of Soil Nails in a Field Slope under Surcharge Loads. J. Appl. Math. 2013, 3, 926097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lanzieri, D.R.; Avesani Neto, J.O. Finite Element Analysis of Soil-Nailed Vertical Excavation in Fine-Grained Soils in an Urban Area. Soils Rocks 2025, 48, e2024010523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, C.; Wu, C.; Lu, M.; Wu, D. System Reliability Analysis of Soil-Nailed Slopes. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 176, 109613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, E.; Varma, M.; Sanoop, G.; Viji, A.J. Parametric Study of Different Soil Nails on Slope Stability Based on Finite Element Method. In Analyses for Retaining Walls, Slope Stability and Landslides, Proceedings of the ICRAGEE 2024, Guwahati, India, 11–14 December 2024; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Sarkar, R., Maheshwari, B., Kumar, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Srivastava, A.; Chauhan, V.B. Numerical Modeling of Soil-Nailed Slope Using Drucker–Prager Model. In Advances in Geo-Science and Geo-Structures; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 154, pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, K.D. Three-Dimensional Stability Analyses of Soil-Nailed Slopes by Finite Element Method. Ph.D. Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Negi, M.S.; Singh, J. Strengthening of Slope by Soil Nailing Using Finite Difference and Limit Equilibrium Methods. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2021, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.-G.; Li, L.; Zhao, L.-H. Stability analysis of slopes reinforced with anchor cables and optimal design of anchor cable parameters. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 2425–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliaei, M.; Norouzi, B.; Binesh, S.M. Evaluation of Soil-Nail Pullout Resistance Using Mesh-Free Method. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 116, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Ramkrishnan, R. Parametric Optimization and Multi-regression Analysis for Soil Nailing Using Numerical Approaches. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 3505–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalehsar, R.I.; Khodaei, M.; Dehghan, A.N.; Najafi, N. Numerical modeling of effect of surcharge load on the stability of nailed soil slopes. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Manna, B.; Sharma, K. Shaking Table Tests to Evaluate the Seismic Performance of Soil Nailing Stabilized Embankments. Int. J. Geomech. 2021, 21, 04021036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, X.; Xu, F. Numerical and experimental studies of the mechanical behaviour for compaction grouted soil nails in sandy soil. Comput. Geotech. 2017, 90, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H.; Ahmed, M.; Mallick, J.; Hoa, P.V. An Experimental Study of a Nailed Soil Slope: Effects of Surcharge Loading and Nails Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afitikhar, A.A.; Aartati, H.K. Finite Element Modelling of Soil Nailing Inclination Effect on Slope Stability: Cibeureum Slope Case Study. Teknisia 2024, 29, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.C.; Aryal, M.; Sharma, K.; Bhandary, N.P.; Pokhrel, R.; Acharya, I.P. Development of a framework for the prediction of slope stability using machine learning paradigms. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H.; Ahmed, M.; Mallick, J.; AlQadhi, S. Finite Element Modeling of the Soil-Nailing Process in Nailed-Soil Slopes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzi, N.I.M.; Radhi, M.S.M.; Win, T.K. Analysis of a Nailed Soil Slope Using Limit Equilibrium and Finite Element Methods—A Review. MATEC Web Conf. 2024, 400, 02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, T.E.; Islam, M.A.; Islam, M.S. Parametric Assessment of Soil Nailing on the Stability of Slopes Using Numerical Approach. Geotechnics 2022, 2, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.-W.; Rajak, R.P. A Numerical Study of a Soil-Nail-Supported Excavation Pit Subjected to a Vertically Loaded Strip Footing at the Crest. Buildings 2024, 14, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramipour, O.; Moezzi, R.; Jalali, F.M.; Khaksar, R.Y.; Gheibi, M. Parametric Evaluation of Soil Nail Configurations for Sustainable Excavation Stability Using Finite Element Analysis. Inventions 2025, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Nezhad, H.M.; Hosseini, S.M.M.M. A numerical study of site effect and dynamic response of staged excavation supported by soil nail walls. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.M.; Chang, G.W.K. Study of Nail soil Interaction by Numerical Shear Box Test Simulations; GEO Report No. 265; Civil Engineering and Development Department: Hong Kong, 2012; 42p. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Bathurst, R. Influence of Selection of Soil and Interface Properties on Numerical Results of Two Soil–Geosynthetic Interaction Problems. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04016136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.M.; Chang, C.Y. Nonlinear Analysis of stress and strain in soil. J. Soil Mech. Found. 1970, 96, 1629–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saran, S. Reinforced Soil and Its Engineering Applications, 2nd ed.; PHI Learning Private Limited: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Constituent | Material | Depth (mm) | Elastic Modulus (kPa) | Bending Stiffness (kN·mm2) | Axial Stiffness (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facing | Perspex | 5.0 | 4200 | 0.04375 | 0.021 |

| Footing | Steel | 22.0 | 21.2 × 107 | 188,186.6 | 4665.78 |

| Maximum Tensile Strength (kPa) | Young’s Modulus (kPa) | Flexural Rigidity, EI (kN·mm2) | Normal Stiffness, EA(kN/m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8.8 × 105 | 21.2 × 107 | 6.51 × 10−3 | 4165.9 |

| Parameter | Hardening Soil | Hardening Soil (Small) | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of material behavior (drainage type) | Drained | Drained | - |

| Bulk unit weight (γunsat) | 16.41 | 16.41 | kN/m3 |

| Saturated unit weight (γsat) | 20.00 | 20.00 | kN/m3 |

| Initial void ratio (einit) | 0.5970 | 0.5970 | |

| Minimum void ratio (emin) | 0.4720 | 0.4720 | |

| Maximum void ratio (emax) | 0.7120 | 0.7120 | |

| Stiffness modulus for oedometer loading (Eoed)ref | 1959 | 1959 | kPa |

| Stiffness modulus for unloading and reloading (Eur)ref | 5877 | 5877 | kPa |

| Power for stress dependency of stiffness (m) | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Compression index (Cc) | 0.1875 | 0.1875 | |

| Swelling index (Cs) | 0.05625 | 0.05625 | |

| Effective cohesion (c′ref) | 0.2 | 0.2 | kPa |

| Effective angle of internal friction (ϕ′) | 34.00 | 34.00 | ° |

| Dilatancy angle (ψ) | 4.000 | 4.000 | ° |

| Poisson’s ratio for unloading and reloading (v′ur) | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | |

| Reference shear modulus at small strains (G0,ref) | --- | 10,000 | kPa |

| Strain level at which the shear modulus is reduced to approximately 70% of G0,ref (γ0.7) | --- | 0.0001 |

| Model Dimension | A (cm) | B (cm) | X (cm) | Z (cm) | Y (cm) | Sh = Sv (cm) | Slope Angle (o) | Nail Length, H = Ln (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 40.5 | 15.0 | 22.5 | 14.6 | 83.4 | 28.0 | 40 | 70.0 |

| Soil Slope Phase | Facing Center Horizontal Displacement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Mesh (No. of Elements (NoE) = 1359 with Size 0.044 m, No. of Nodes (NoN) = 11,543) | Medium Mesh (NoE = 1975 with Size 0.0354 m, NoN = 16,679) | Fine Mesh (NoE = 4085 with Size 0.0246 m, NoN = 33,987) | |

| Phase 3 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.050 |

| Phase 5 | 0.079 | 0.082 | 0.085 |

| Phase 6 | 0.146 | 0.158 | 0.156 |

| Phase 8 | 0.466 | 0.525 | 0.528 |

| Soil Slope Phase | Footing Settlement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Mesh | Medium Mesh | Fine Mesh | |

| Phase 6 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.68 |

| Phase 7 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.77 |

| Phase 8 | 1.63 | 1.51 | 1.83 |

| Soil Slope Phase | Factor of Safety | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Mesh | Medium Mesh | Fine Mesh | |

| Phase 5 | 1.467 | 1.440 | 1.387 |

| Phase 6 | 1.534 | 1.513 | 1.436 |

| Phase 7 | 1.476 | 1.442 | 1.404 |

| Phase 8 | 1.303 | 1.261 | 1.227 |

| Soil Slope Phase | Factor of Safety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Soil Slope Dimensions | Increased Vertical Dimension | Increased Horizontal Dimension | Prototype Dimension | Three Dimensions (3D) | |

| Phase 5 | 1.440 | 1.488 | 1.448 | 1.327 | 1.666 |

| Phase 6 | 1.513 | 1.534 | 1.511 | 1.260 | 1.637 |

| Phase 7 | 1.442 | 1.445 | 1.447 | 1.273 | 1.579 |

| Phase 8 | 1.261 | 1.266 | 1.280 | 1.090 | 1.376 |

| Soil Slope Phase | Factor of Safety | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Angle = 40° (HS) | Angle = 40° [HS (Small)] | Angle = 45° (HS) | |

| Phase 5 | 1.440 | 1.422 | 1.266 |

| Phase 6 | 1.513 | 1.498 | 1.317 |

| Phase 7 | 1.442 | 1.442 | 1.244 |

| Phase 8 | 1.261 | 1.271 | 1.132 |

| Soil Slope Phase | Factor of Safety | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Nail Length in Each Layer | Redistributed Nail Length in Layers | Progressive Reduced Nail Length in Layers | |

| Phase 5 | 1.440 | 1.449 | 1.334 |

| Phase 6 | 1.513 | 1.494 | 1.361 |

| Phase 7 | 1.442 | 1.477 | 1.291 |

| Phase 8 | 1.261 | 1.302 | 1.131 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarmom, S.A.; Ahmed, M.; Mohamed, M.H.; Alkahtani, M.Q.; Mallick, J. Finite Element Parametric Study of Nailed Non-Cohesive Soil Slopes. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122125

Tarmom SA, Ahmed M, Mohamed MH, Alkahtani MQ, Mallick J. Finite Element Parametric Study of Nailed Non-Cohesive Soil Slopes. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122125

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarmom, Sohaib Ali, Mohd. Ahmed, Mahmoud H. Mohamed, Meshel Q. Alkahtani, and Javed Mallick. 2025. "Finite Element Parametric Study of Nailed Non-Cohesive Soil Slopes" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122125

APA StyleTarmom, S. A., Ahmed, M., Mohamed, M. H., Alkahtani, M. Q., & Mallick, J. (2025). Finite Element Parametric Study of Nailed Non-Cohesive Soil Slopes. Symmetry, 17(12), 2125. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122125