Modeling Computer Virus Spread Using ABC Fractional Derivatives with Mittag-Leffler Kernels: Symmetry, Invariance, and Memory Effects in a Four-Compartment Network Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Summary of structural symmetries: Infection pressure: symmetric sum . Equivariance: for . Invariant geometry: forward invariance of the cone and simplex. Stability symmetry: identical Hyers–Ulam bounds for L and I.

2. Background

- 1.

- Linearity: For any and functions in the domain of ,

- 2.

- Non-singular kernel: Unlike classical Riemann–Liouville or Caputo operators, the CAB derivative employs the Mittag-Leffler kernel, which is non-singular and non-local, thus avoiding divergence at and capturing long-memory effects.

- 3.

- Consistency with integer order: If , thenand if , the derivative is reduced to , thereby bridging fractional and integer-order calculus.

- 4.

- Positivity of the kernel: The kernel is positive and decreasing in t, which ensures that the CAB operator preserves non-negativity in dynamical systems.

- 5.

- Memory effect: The non-local structure implies that depends on the entire history of for , capturing hereditary and fading memory effects crucial in modeling biological and digital epidemics.

3. Mathematical Model of Fractional-Order for Malware Propagation

- : Number of vulnerable devices at time t.

- : Number of devices carrying latent (dormant) infections.

- : Number of actively infected devices spreading malware.

- : Number of antivirus-protected devices.

- : Rate of device addition and removal.

- : Malware transmission rate.

- : Transition rate from latent to active infection.

- : Transition rate from infection to antivirus-protected state.

- : Neutralization rate of antivirus-protected devices.

- Malware-Free Equilibrium (MFE): Malware is eradicated due to effective defenses.

- Endemic Malware Equilibrium (EME): Malware persists due to inadequate protection or rapid spread.

- Susceptible humans → Vulnerable devices: In epidemiology, susceptible individuals can contract a disease; in networks, vulnerable computers without antivirus protection can be infected by malware.

- Latent (exposed) humans → Covertly infected devices: In biology, exposed individuals carry the pathogen but do not yet show symptoms; similarly, a device may host hidden malware that is not yet spreading but is capable of becoming active later.

- Infectious humans → Actively contagious devices: An infectious person can spread disease; likewise, an actively infected computer spreads malware through connections, downloads, or shared files.

- Recovered humans → Antivirus-protected devices: Just as recovery with immunity prevents reinfection, installation of antivirus software protects devices from further infection or neutralizes active threats.

- 1.

- (Symmetric infection pressure) The S-equation depends on L and I only through the symmetric combination .

- 2.

- (Invariant cone/simplex) The nonnegative orthant is forward invariant. If the variables are normalized by to lie in , then Δ is forward invariant.

- 3.

- (Equivariance under -swap) If and the linear loss terms of L and I are equal, then the vector field is equivariant under the action ; i.e., .

4. The Solution of the Proposed Mathematical Model

4.1. Positivity and Uniform Boundedness of Solutions

- Step 2 (Quasi-positivity of the vector field). Let . A vector field F is quasi–positive on if

- Hence F is quasi–positive on .

- Step 3 (First-exit contradiction). Let . Assume, for contradiction, that the solution exits K. Define the first exit timeBy continuity, for and . Thus, for some component, say , we have and on .

- Step 4 (Component-wise boundary checks, explicit). For completeness, evaluating at the faces of K:which is exactly the quasi-positivity used above.

4.2. Existence and Uniqueness of Solutions

4.3. Hyers–Ulam Stability

4.4. Analytic Solution of the CAB Fractional Computer Virus Model

4.5. Iterative Variation-of-Parameters Technique

5. Numerical Approximation Scheme

5.1. Numerical Experiments with Varying Initial Conditions

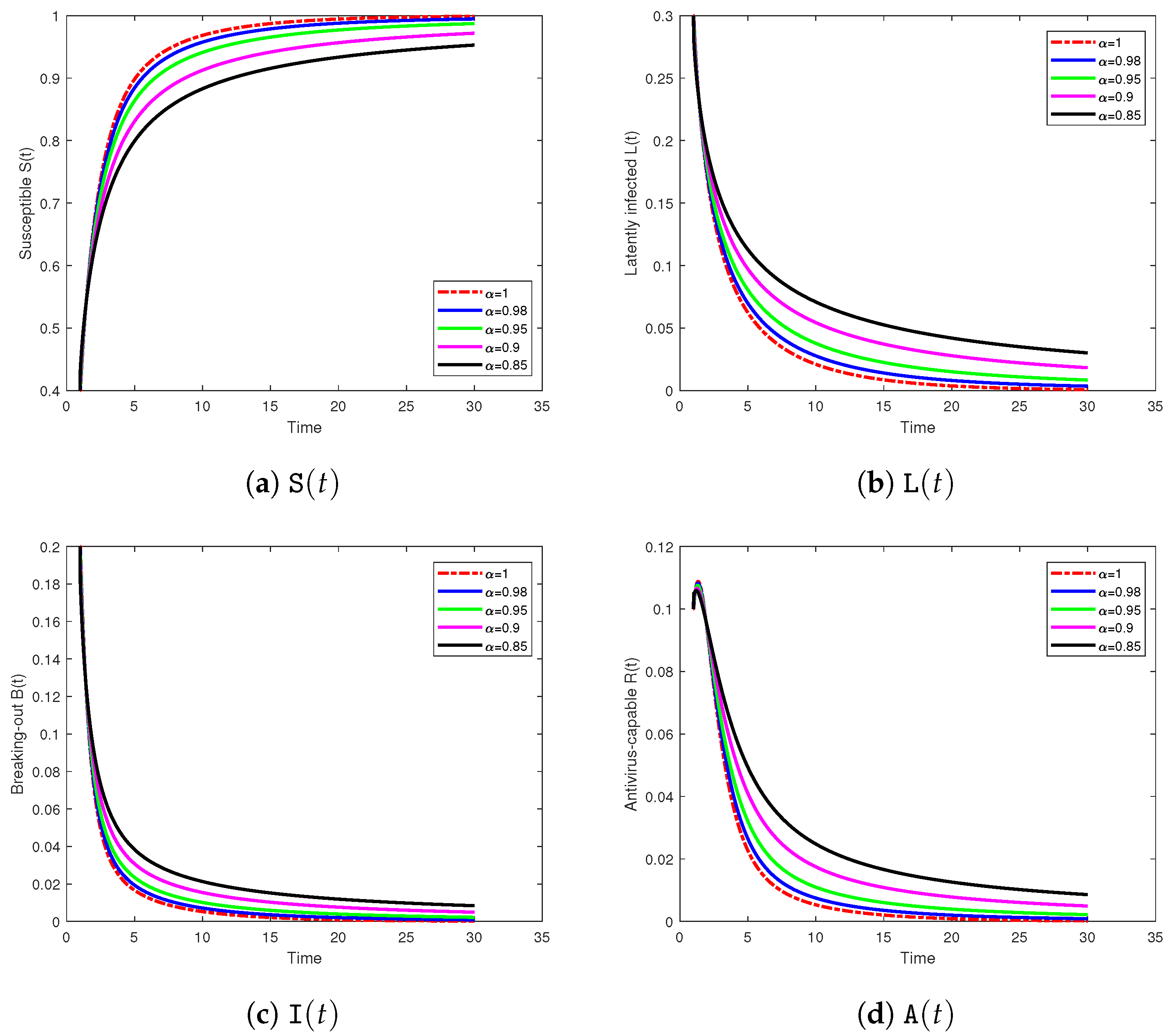

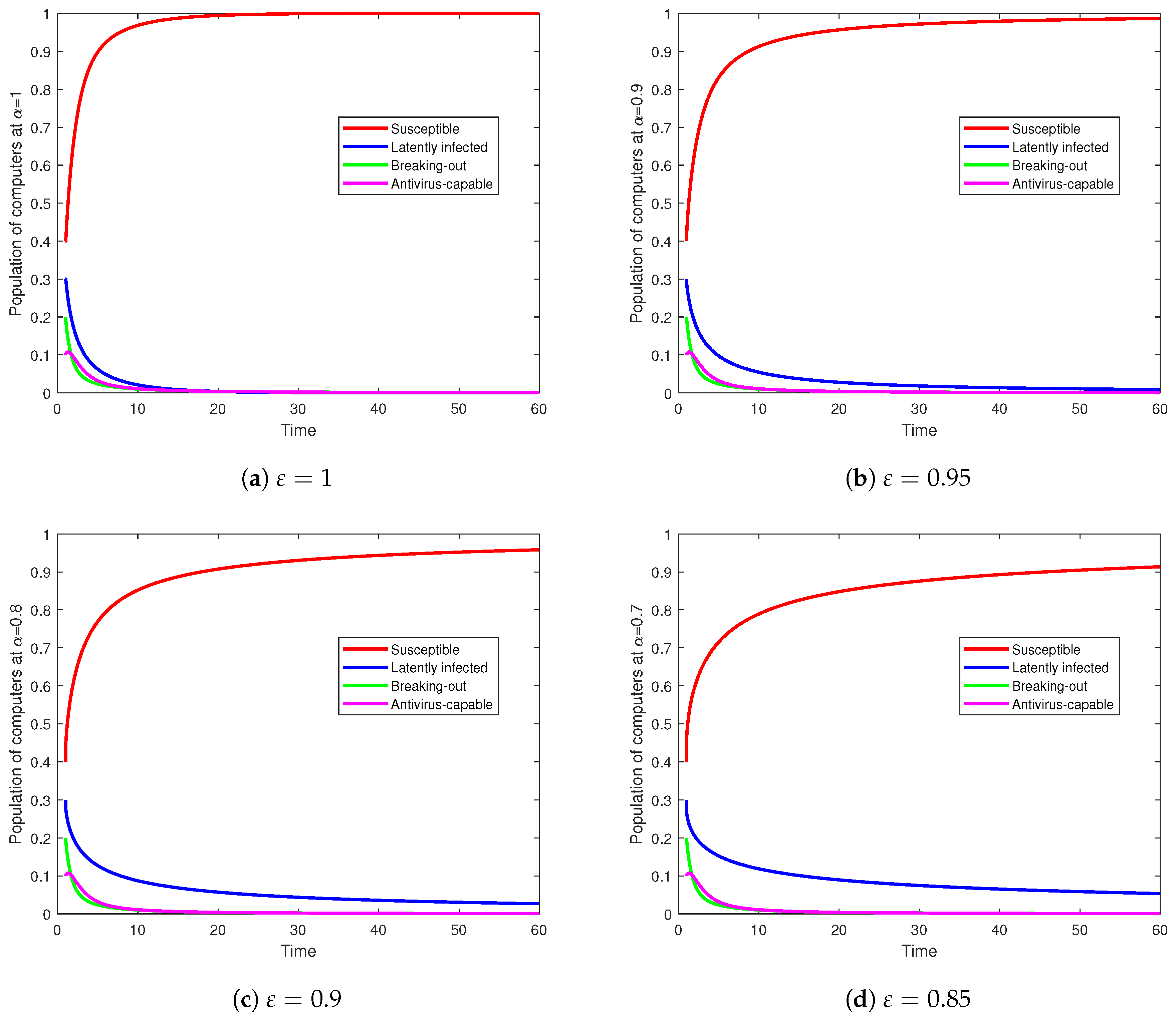

- Qualitative findings (consistent across parameters used).

- Peak size and timing (in ). Increasing (LS → MOD → HS) monotonically increases the early growth rate and advances the time-to-peak. For the same parameters, the HS scenario reaches a larger peak earlier than LS.

- Latency reservoir (). Larger seeds a larger latent pool via , producing a broader shoulder before decay. This effect is more pronounced for smaller due to stronger memory.

- Protected devices (). Since A grows through , scenarios with larger accumulate protection more rapidly and saturate earlier; small slows the relaxation, yielding longer tails in .

- Effect of fractional order. For fixed initial data, smaller delays peaks and lengthens transients (consistent with the order-sweep results), but the ordering across initial-condition scenarios (HS > MOD > LS in early growth and peak size) is preserved.

5.2. Strategy for Choosing Parameters

- Turnover rate . This was fixed at to represent moderate addition and removal of devices within the network. The value was chosen to balance the inflow of susceptible devices with the natural loss of old or offline systems, ensuring that the system does not trivially collapse to zero population.

- Transmission rate . We considered two scenarios: for a baseline “safe state’’ with limited malware spread, and for a more aggressive “infectious state.’’ These values were selected to span the range of moderate-to-high transmission observed in analogous epidemic models, and to test how the system transitions between malware-free and endemic states.

- Latency-to-activation rate . The small value was chosen to capture the realistic property of modern malware, which often remains dormant for extended periods before becoming active. This reflects the hidden threat of stealth infections.

- Antivirus activation rate . We set to model an intermediate level of antivirus responsiveness: not instantaneous but not negligible. This allows us to test the influence of delayed security deployment on system stability.

- Protected-device removal rate . The value was selected to represent moderate loss of antivirus protection, such as through outdated signatures or unpatched software. A higher value would lead to rapid reinfection, while a lower value would imply unrealistically permanent immunity.

5.3. Numerical Study

6. Discussion

- Low seed (). The outbreak onset is slow and antivirus activation is delayed.

- Moderate seed (). The peak occurs earlier and is higher, and protection ramps up sooner.

- High seed (). A rapid early peak is followed by faster growth of ; memory still prolongs recovery relative to .

- Device turnover . This term injects and removes devices, sustaining susceptibility when large.

- Transmission . It governs infection pressure; higher values push the system toward endemicity.

- Latency activation . Small yields long dormant phases before devices become infectious.

- Antivirus activation . Larger shortens infectious periods and accelerates protection.

- Protection loss . Larger erodes immunity and raises reinfection risk.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Okaka, F.O.; Ojeh, V.N. Mathematical model of pneumonia misdiagnosed as malaria. IOSR J. Math. 2013, 6, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Okaka, F.O.; Chukwuocha, E.O. Modeling concurrent malaria-typhoid infection. Open J. Model. Simul. 2015, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Steady, A.M.; Nwafor, G.I. Deterministic model of typhoid fever in malaria endemic areas. Int. J. Math. Anal. 2014, 8, 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Adeboye, A.D.; Omame, A. Modeling co-infection of malaria and typhoid. J. Adv. Math. Comput. Sci. 2015, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbas, A.A.; Srivastava, H.M.; Trujillo, J.J. Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mainardi, F. Fractional Calculus and Waves in Linear Viscoelasticity; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Samko, S.G.; Kilbas, A.A.; Marichev, O.I. Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: Theory and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, M.; Fabrizio, M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Progr. Fract. Differ. Appl. 2015, 1, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Atangana, A.; Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2016, 89, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Baleanu, D.; Jajarmi, A.; Hajipour, M. On nonlinear dynamical systems with generalized fractional derivatives. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 94, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarad, F.; Abdeljawad, T.; Baleanu, D. On the generalized Caputo fractional derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 123, 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Gorenflo, R.; Loutchko, J.; Luchko, Y. Computation of the Mittag-Leffler function. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2002, 5, 491–518. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, R.; Bastos, N.R.O.; Torres, D.F.M. A Caputo fractional derivative of variable order with applications. Comput. Math. Appl. 2017, 66, 876–889. [Google Scholar]

- Losada, J.; Nieto, J.J. Properties of a new fractional derivative without singular kernel. Progr. Fract. Differ. Appl. 2015, 1, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed, A.M.A.; El-Mesiry, A.; El-Saka, H. Fractional logistic equation. Appl. Math. Lett. 2007, 20, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; Elgazzar, A. On fractional order differential equations model for nonlocal epidemics. Physica A 2007, 379, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboubakar, H.; Kumar, P.; Erturk, V.S.; Kumar, A. A mathematical study of a tuberculosis model with fractional derivatives. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 2021, 12, 2150037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.K.; Kang, B.; Koo, N. Stability for Caputo fractional differential systems. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014, 2014, 631419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubyani, M.; Saber, S. Hyers–Ulam stability of fractal–fractional computer virus models with the Atangana–Baleanu operator. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.K.; Saini, D. Mathematical models on computer viruses. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 187, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, S.; Alahmari, A. Impact of Fractal-Fractional Dynamics on Pneumonia Transmission Modeling. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2025, 18, 5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubyani, M.; Taha, N.E.; Taha, K.O.; Alharb, R.A.; Saber, S. Epidemiological Modeling of Pneumococcal Pneumonia: Insights from ABC Fractal-Fractional Derivatives. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 143, 3491–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, O.J.; Yusuf, A.; Oshinubi, K.; Oguntolu, F.A.; Lawal, J.O.; Abioye, A.I.; Ayoola, T.A. Fractional order of pneumococcal pneumonia infection model with Caputo–Fabrizio operator. Results Phys. 2021, 29, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelregal, A.E.; Askar, S.S.; Marin, M.; Mohamed, B. The theory of thermoelasticity with a memory-dependent dynamic response for a thermo-piezoelectric functionally graded rotating rod. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobiny, A.; Abbas, I.; Marin, M. The Influences of the Hyperbolic Two-Temperatures Theory on Waves Propagation in a Semiconductor Material Containing Spherical Cavity. Mathematics 2022, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, A.; Khan, M.I.; Ellahi, R.; Marin, M. Computational Intelligence Approach for Optimising MHD Casson Ternary Hybrid Nanofluid over the Shrinking Sheet with the Effects of Radiation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.; Hobiny, A.; Abbas, I. The Effects of Fractional Time Derivatives in Porothermoelastic Materials Using Finite Element Method. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T.; Abbas, I.; Marin, M. A GL Model on Thermo-Elastic Interaction in a Poroelastic Material Using Finite Element Method. Symmetry 2020, 12, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, S.; Solouma, E. Advanced fractional modeling of diabetes: Bifurcation analysis, chaos control, and a comparative study of numerical methods adams-bashforth-moulton and laplace-adomian-padé method. Indian J. Phys. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, S.; Mirgani, S.M. Numerical solutions, stability, and chaos control of Atangana-Baleanu variable-order derivatives in glucose-insulin dynamics. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Mech. 2025, 24, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, S.; Mirgani, S. Analyzing fractional glucose-insulin dynamics using Laplace residual power series methods via the Caputo operator: Stability and chaotic behavior. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2025, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, M.; Aljohani, A.F.; Taha, N.E.; Abdel-Khalek, S.; Bayram, M.; Saber, S. Application of a fractal fractional operator to nonlinear glucose-insulin systems: Adomian decomposition solutions. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 196, 110453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhazmi, M.; Saber, S. Application of a fractal fractional derivative with a power-law kernel to the glucose-insulin interaction system based on Newton’s interpolation polynomials. Fractals 2025, 25402017. [Google Scholar]

- Saber, S.; Dridi, B.; Alahmari, A.; Messaoudi, M. Application of Jumarie-Stancu Collocation Series Method and Multi-Step Generalized Differential Transform Method to fractional glucose-insulin. Int. J. Optim. Control Theor. Appl. 2025, 15, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, S.; Dridi, B.; Alahmari, A.; Messaoudi, M. Hyers-Ulam Stability and Control of Fractional Glucose-Insulin Systems. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2025, 18, 6152. [Google Scholar]

- Althubyani, M.; Adam, H.D.; Alalyani, A.; Taha, N.E.; Taha, K.O.; Alharbi, R.A.; Saber, S. Understanding zoonotic disease spread with a fractional order epidemic model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, H.D.; Althubyani, M.; Mirgani, S.M.; Saber, S. An application of Newton’s interpolation polynomials to the zoonotic disease transmission between humans and baboons system based on a time-fractal fractional derivative with a power-law kernel. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 045217. [Google Scholar]

- Saber, S.; Solouma, E. The Generalized Euler Method for Analyzing Zoonotic Disease Dynamics in Baboon-Human Populations. Symmetry 2025, 17, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, S.; Solouma, E.; Althubyani, M.; Messaoudi, M. Statistical insights into zoonotic disease dynamics: Simulation and control strategy evaluation. Symmetry 2025, 17, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, S.; Alahmari, A. Mathematical insights into zoonotic disease spread: Application of the Milstein method. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2025, 18, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechee, M.S.; Salman, Z.I.; Alkufi, S.Y. Novel Definitions of α-Fractional Integral and Derivative of the Functions. Iraqi J. Sci. 2023, 64, 5866–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulam, S.M. A Collection of Mathematical Problems; Interscience Publ.: Geneva, Switzerland, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Jajarmi, A.; Baleanu, D.; Sayevand, K. A new fractional optimal control model for biological systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2019, 69, 431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-De-León, C. Volterra-type Lyapunov functions for fractional-order epidemic systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2015, 24, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zeng, F. The Finite Difference Methods for Fractional Ordinary Differential Equations. Numer. Funct. Anal. Optim. 2013, 34, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, N. The predictor-corrector solution for fractional order differential algebraic equation. In Proceedings of the ICFDA’14 International Conference on Fractional Differentiation and Its Applications 2014, Catania, Italy, 23–25 June 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, M.; Dawalbait, F.M.; Aljohani, A.; Taha, K.O.; Adam, H.D.; Saber, S. Numerical approximation method and chaos for a chaotic system in sense of Caputo-Fabrizio operator. Therm. Sci. 2024, 28, 5161–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Alhazmi, M.; Youssif, M.Y.; Elhag, A.E.; Aljohani, A.F.; Saber, S. Analysis of a Lorenz model using Adomian decomposition and fractal-fractional operators. Therm. Sci. 2024, 28, 5001–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, A.; Alharb, R.A.; Albogami, T.M.; Eljaneid, N.H.; Adam, H.D.; Saber, S.F. Controlled chaos of a fractal–fractional Newton-Leipnik system. Therm. Sci. 2024, 28, 5153–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.I.A.; Mirgani, S.M.; Seadawy, A.; Saber, S. A comprehensive investigation of fractional glucose-insulin dynamics: Existence, stability, and numerical comparisons using residual power series and generalized Runge-Kutta methods. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2025, 19, 2460280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiman, A. Über den Fundamentalsatz in der Theorie der Funktionen Eα(x). Acta Math. 1905, 29, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenflo, R.; Kilbas, A.A.; Mainardi, F.; Rogosin, S.V. Mittag-Leffler Functions, Related Topics and Applications; Springer Monographs in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittag-Leffler, G.M. Sur la nouvelle fonction E(x). Comptes Rendus De L’academie Des Sci. Paris 1903, 137, 554–558. [Google Scholar]

| Scenario | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-seed (LS) | ||||

| Moderate (MOD) | ||||

| High-seed (HS) |

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rate of network device addition/removal | ||

| Malware transmission rate | (safe), (infectious) | |

| Transition from latent to active infection | ||

| Transition from infection to antivirus-protected state | ||

| Removal/neutralization rate of protected devices |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saber, S.; Solouma, E.; Alsulami, M. Modeling Computer Virus Spread Using ABC Fractional Derivatives with Mittag-Leffler Kernels: Symmetry, Invariance, and Memory Effects in a Four-Compartment Network Model. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1891. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111891

Saber S, Solouma E, Alsulami M. Modeling Computer Virus Spread Using ABC Fractional Derivatives with Mittag-Leffler Kernels: Symmetry, Invariance, and Memory Effects in a Four-Compartment Network Model. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1891. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111891

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaber, Sayed, Emad Solouma, and Mansoor Alsulami. 2025. "Modeling Computer Virus Spread Using ABC Fractional Derivatives with Mittag-Leffler Kernels: Symmetry, Invariance, and Memory Effects in a Four-Compartment Network Model" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1891. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111891

APA StyleSaber, S., Solouma, E., & Alsulami, M. (2025). Modeling Computer Virus Spread Using ABC Fractional Derivatives with Mittag-Leffler Kernels: Symmetry, Invariance, and Memory Effects in a Four-Compartment Network Model. Symmetry, 17(11), 1891. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111891