Secure Quantum Teleportation of Squeezed Thermal States

Abstract

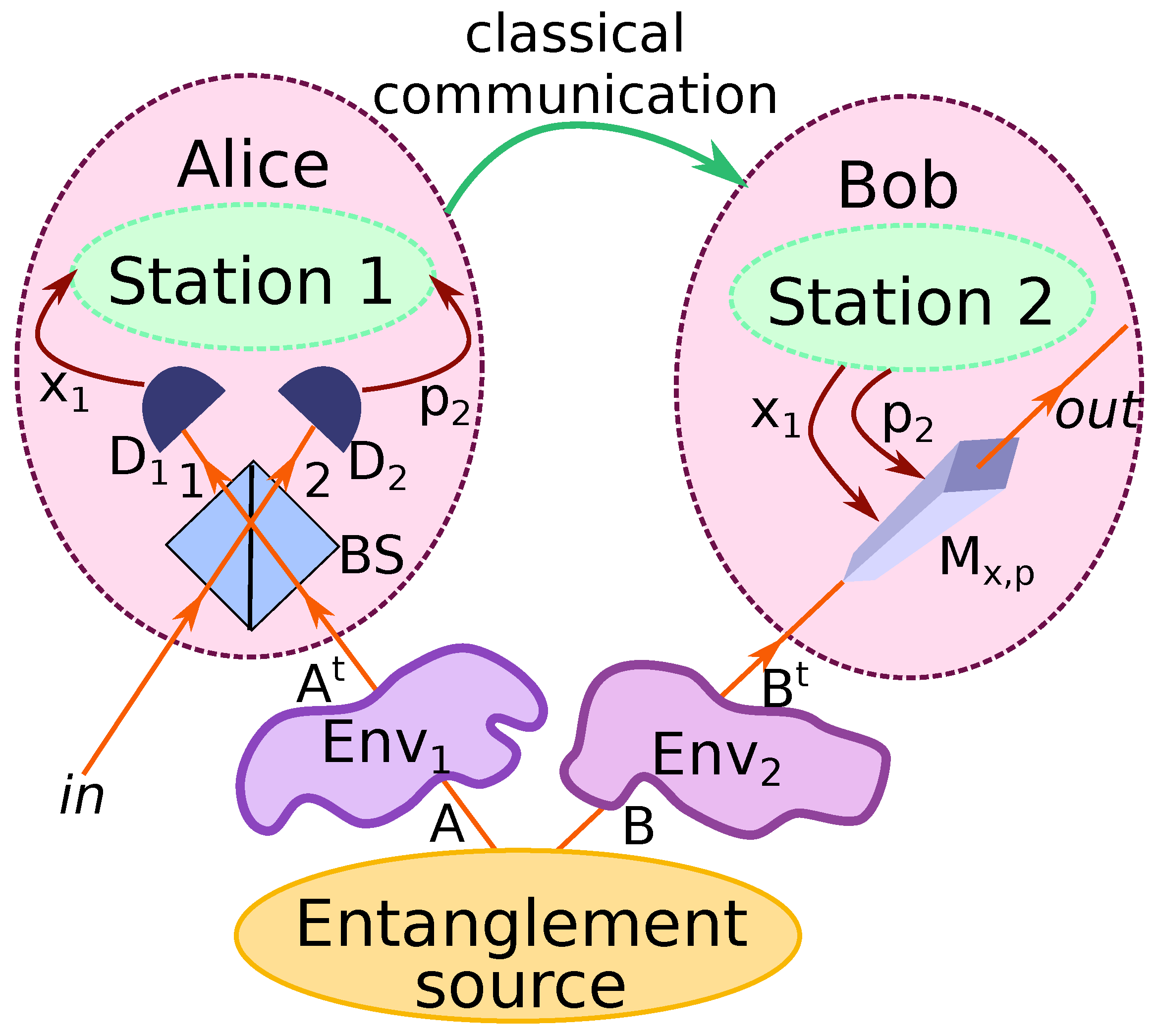

1. Introduction

2. Criteria for Successful Secure Quantum Teleportation

2.1. Teleportation of a Squeezed Thermal State

- Expressing the analytical formula for the fidelity of teleportation in terms of the covariance matrices of the input and output states.

- Writing the characteristic function of the output state in terms of its covariance matrix and mean displacement vector.

- Expressing the characteristic function of the output state in terms of the characteristic functions of the input state and the resource state at time t.

- Deriving the formula for the covariance matrix of the output state based on the two previous expressions.

2.2. Classical Limit for Squeezed Thermal State Teleportation

2.3. Quantum Steering of the Resource State

2.4. Evolution of a Two-Mode Gaussian State in the Two-Reservoir Model

3. Main Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G.; Crépeau, C.; Jozsa, R.; Peres, A.; Wootters, W.K. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 1895–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidman, L. Teleportation of quantum states. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 49, 1473–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserkis, S.; Hosseinidehaj, N.; Walk, N.; Ralph, T.C. Teleportation-based collective attacks in Gaussian quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 013208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Isidoro, C.; Delgado, F. Shared Quantum Key Distribution Based on Asymmetric Double Quantum Teleportation. Symmetry 2022, 14, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Economou, S.E.; Elkouss, D.; Hilaire, P.; Jiang, L.; Lo, H.K.; Tzitrin, I. Quantum repeaters: From quantum networks to the quantum internet. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2023, 95, 045006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, D.; Drmota, P.; Nadlinger, D.; Ainley, E.; Agrawal, A.; Nichol, B.; Srinivas, R.; Araneda, G.; Lucas, D. Distributed quantum computing across an optical network link. Nature 2025, 638, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapatero, V.; van Leent, T.; Arnon-Friedman, R.; Liu, W.Z.; Zhang, Q.; Weinfurter, H.; Curty, M. Advances in device-independent quantum key distribution. Npj Quantum Inf. 2023, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseiny, S.M.; Seyed-Yazdi, J.; Norouzi, M. Quantum teleportation and remote sensing through semiconductor quantum dots affected by pure dephasing. Front. Phys. 2024, 20, 024201. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciapuoti, A.S.; Caleffi, M.; Van Meter, R.; Hanzo, L. When Entanglement Meets Classical Communications: Quantum Teleportation for the Quantum Internet. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2020, 68, 3808–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centrone, F.; Diamanti, E.; Kerenidis, I. Quantum Protocol for Electronic Voting without Election Authorities. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2022, 18, 014005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Dev, K.; Siljak, H.; Joshi, H.D.; Magarini, M. Quantum Internet—Applications, Functionalities, Enabling Technologies, Challenges, and Research Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2021, 23, 2218–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacchi, B.; Leichtle, D.; Limongi, L.; Carvacho, G.; Milani, G.; Spagnolo, N.; Kaplan, M.; Sciarrino, F.; Kashefi, E. Multi-client distributed blind quantum computation with the Qline architecture. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nande, S.S.; Habibie, M.I.; Ghadimi, M.; Garbugli, A.; Kondepu, K.; Bassoli, R.; Fitzek, F.H. Integrating quantum synchronization in future generation networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohageg, M.; Mazzarella, L.; Anastopoulos, C.; Gallicchio, J.; Hu, B.L.; Jennewein, T.; Johnson, S.; Lin, S.Y.; Ling, A.; Marquardt, C.; et al. The deep space quantum link: Prospective fundamental physics experiments using long-baseline quantum optics. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2022, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weedbrook, C.; Pirandola, S.; García-Patrón, R.; Cerf, N.J.; Ralph, T.C.; Shapiro, J.H.; Lloyd, S. Gaussian quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 621–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asavanant, W.; Furusawa, A. Multipartite continuous-variable optical quantum entanglement: Generation and application. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 040101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.X.; Tan, H.T.; Wu, S.P.; Huang, G.M. Deterministic generation of a pure continuous-variable entangled state for two ions trapped in a cavity. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 025801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, U.; Sahoo, S.N.; Singh, A.; Joarder, K.; Chatterjee, R.; Chakraborti, S. Single-Photon Sources. Opt. Photon. News 2019, 30, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cao, C.; Feng, Z.; Ye, S.; Li, M.; Song, B.; Wei, R. Factors influencing the performance of optical heterodyne detection system. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 171, 107826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzman, I.; Ivry, Y. Superconducting Nanowires for Single-Photon Detection: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2019, 2, 1800058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Pirandola, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, C.; Chu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, B.; Yu, S.; Guo, H. Long-Distance Continuous-Variable Quantum Key Distribution over 202.81 km of Fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 010502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Weedbrook, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Continuous-variable QKD over 50 km commercial fiber. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish, S.P.; Gleeson, P.J.; Walsh, A.; Lam, P.K.; Assad, S.M. Comparison of discrete variable and continuous variable quantum key distribution protocols with phase noise in the thermal-loss channel. Quantum 2024, 8, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, O. Continuous-variable quantum computing in the quantum optical frequency comb. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2019, 53, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Qin, J.; Cheng, J.; Yan, Z.; Qin, Z.; Su, X.; Jia, X.; Xie, C.; Peng, K. Deterministic quantum teleportation through fiber channels. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Beni, J.; Paparelle, I.; Parigi, V.; Giorgi, G.L.; Soriano, M.C.; Zambrini, R. Quantum machine learning via continuous-variable cluster states and teleportation. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2025, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Jeng, H.; Conlon, L.O.; Tserkis, S.; Shajilal, B.; Liu, K.; Ralph, T.C.; Assad, S.M.; Lam, P.K. Enhancing quantum teleportation efficacy with noiseless linear amplification. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiurášek, J. Analysis of continuous-variable quantum teleportation enhanced by measurement-based noiseless quantum amplification. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 2527–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, A.; Olivares, S.; Paris, M. Gaussian States in Quantum Information; Napoli Series on Physics and Astrophysics; Bibliopolis: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zubarev, A.; Cuzminschi, M.; Isar, A. Continuous variable quantum teleportation of a thermal state in a thermal environment. Results Phys. 2022, 39, 105700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Rosales-Zárate, L.; Adesso, G.; Reid, M.D. Secure Continuous Variable Teleportation and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 180502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosshans, F.; Grangier, P. Quantum cloning and teleportation criteria for continuous quantum variables. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 010301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, D.; Abbasnezhad, F.; Mehrabankar, S.; Isar, A. Two-mode Gaussian states as resource of secure quantum teleportation in open systems. Chin. J. Phys. 2020, 68, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabankar, S.; Mahmoudi, P.; Abbasnezhad, F.; Afshar, D.; Isar, A. Effect of noisy environment on secure quantum teleportation of unimodal Gaussian states: S. Mehrabankar et al. Quantum Inf. Process. 2024, 23, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozsa, R. Fidelity for Mixed Quantum States. J. Mod. Opt. 1994, 41, 2315–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, P.; Marian, T.A. Uhlmann fidelity between two-mode Gaussian states. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 022340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scutaru, H. Fidelity for displaced squeezed thermal states and the oscillator semigroup. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1998, 31, 3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, G. Continuous-variable quantum teleportation in bosonic structured environments. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 034305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, L.; Braunstein, C.A.F.; Kimble, H.J. Criteria for continuous-variable quantum teleportation. J. Mod. Opt. 2000, 47, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesso, G.; Chiribella, G. Quantum Benchmark for Teleportation and Storage of Squeezed States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 170503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Bao, W.S.; Li, H.W.; Zhou, C.; Li, Y. Finite-key analysis for one-sided device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 052322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.J.; Wiseman, H.M.; Doherty, A.C. Entanglement, Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen correlations, Bell nonlocality, and steering. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 052116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uola, R.; Costa, A.C.; Nguyen, H.C.; Gühne, O. Quantum steering. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020, 92, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiurášek, J. Gaussian Transformations and Distillation of Entangled Gaussian States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 137904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, H.M.; Jones, S.J.; Doherty, A.C. Steering, Entanglement, Nonlocality, and the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 140402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogias, I.; Lee, A.R.; Ragy, S.; Adesso, G. Quantification of Gaussian Quantum Steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 060403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, V.; Kossakowski, A.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. Completely positive dynamical semigroups of N-level systems. J. Math. Phys. 1976, 17, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isar, A.; Sandulescu, A.; Scutaru, H.; Stefanescu, E.; Scheid, W. Open quantum systems. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 1994, 3, 635–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isar, A. Entanglement dynamics of two-mode Gaussian systems in a two-reservoir model. Phys. Scr. 2014, 2014, 014019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sǎndulescu, A.; Scutaru, H. Open quantum systems and the damping of collective modes in deep inelastic collisions. Ann. Phys. 1987, 173, 277–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, P.; Marian, T.A.; Scutaru, H. Bures distance as a measure of entanglement for two-mode squeezed thermal states. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 68, 062309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram Research, Inc. Mathematica; Version 11.0.4; Wolfram Research, Inc.: Champaign, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.X.; Fang, X.X.; Lu, H. Experimental distillation of tripartite quantum steering with an optimal local filtering operation. Photon. Res. 2024, 12, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, Y.; Ahansaz, B. Maximal-steered-coherence protection by quantum reservoir engineering. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 020402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukawa, M.; Benichi, H.; Furusawa, A. High-fidelity continuous-variable quantum teleportation toward multistep quantum operations. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 77, 022314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, N.; Aoki, T.; Koike, S.; Yoshino, K.i.; Wakui, K.; Yonezawa, H.; Hiraoka, T.; Mizuno, J.; Takeoka, M.; Ban, M.; et al. Experimental demonstration of quantum teleportation of a squeezed state. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 042304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-X.; Xie, C.D.; Peng, K.-C. Fidelity of Quantum Teleportation for Single-Mode SqueezedState Light. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2005, 22, 3005. [Google Scholar]

- Olivares, S.; Paris, M.G.A.; Andersen, U.L. Cloning of Gaussian states by linear optics. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 73, 062330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

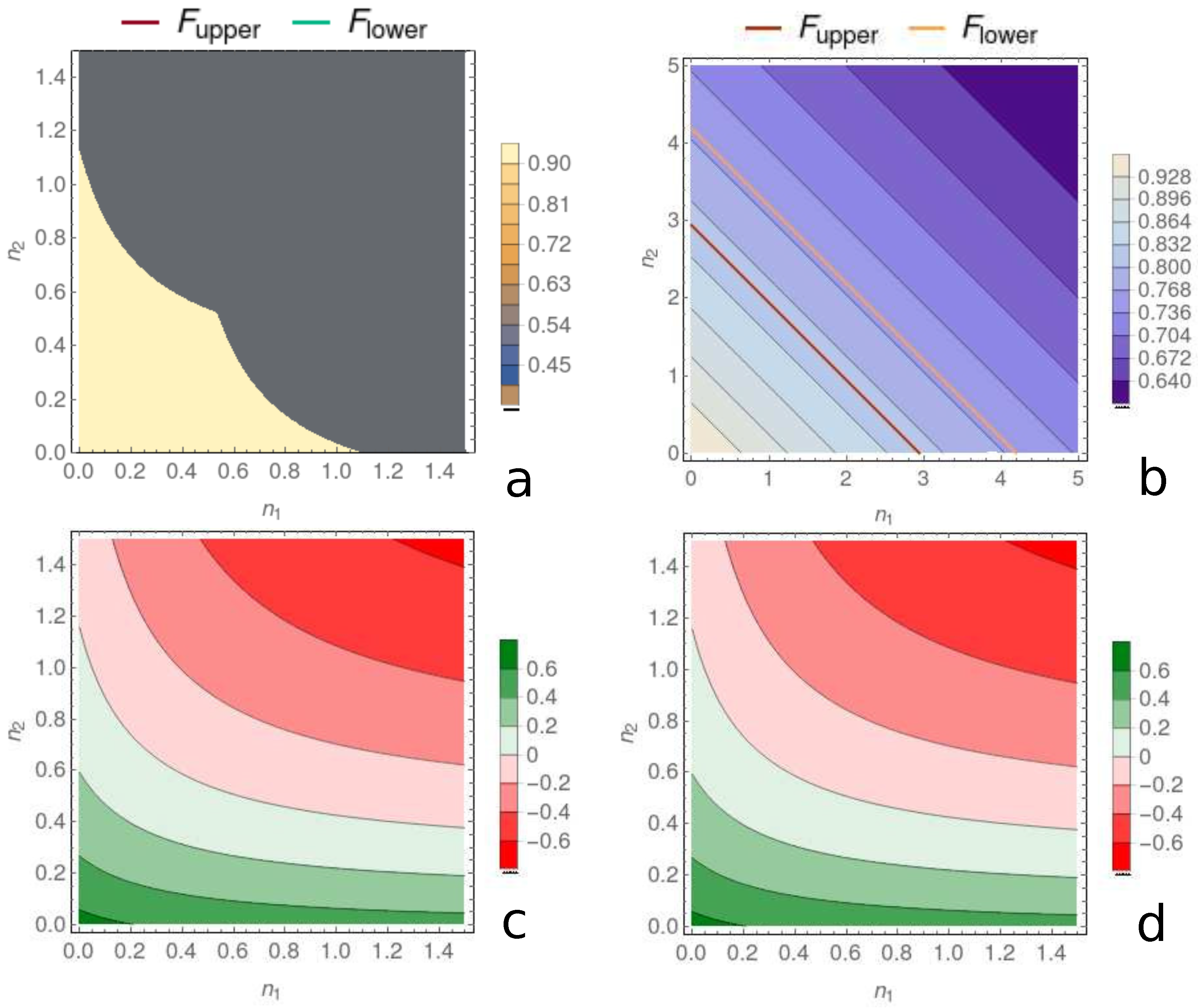

| Figure | Value | r | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

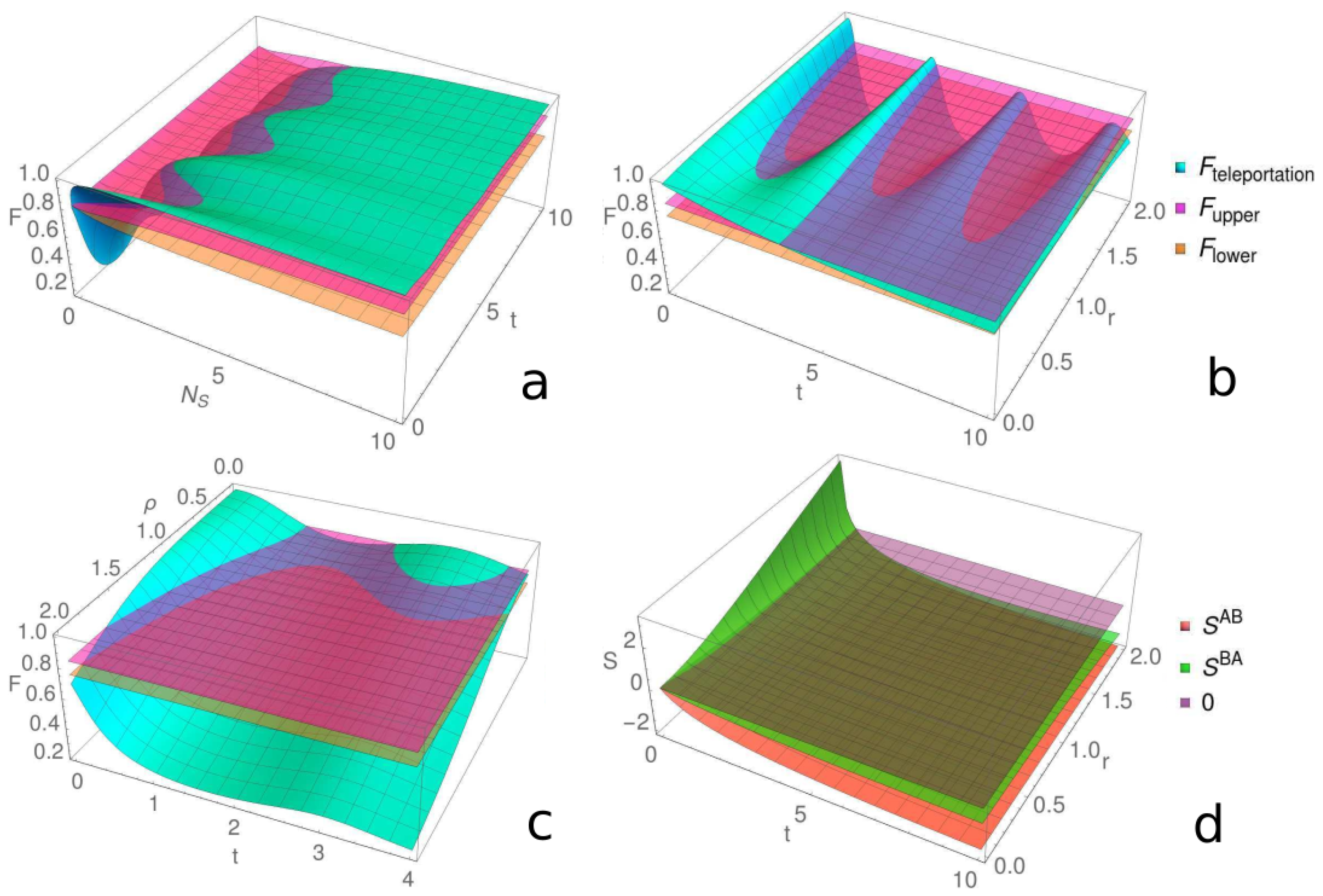

| Figure 3a | F | 0 | 1 | 1 | t | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Figure 3b | F | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | t | 1 | 4 | r | 0 | 0 | |

| Figure 3c | F | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | t | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Figure 3d | , | − | − | − | 1 | 1 | t | 1 | 4 | r | 0 | 0 |

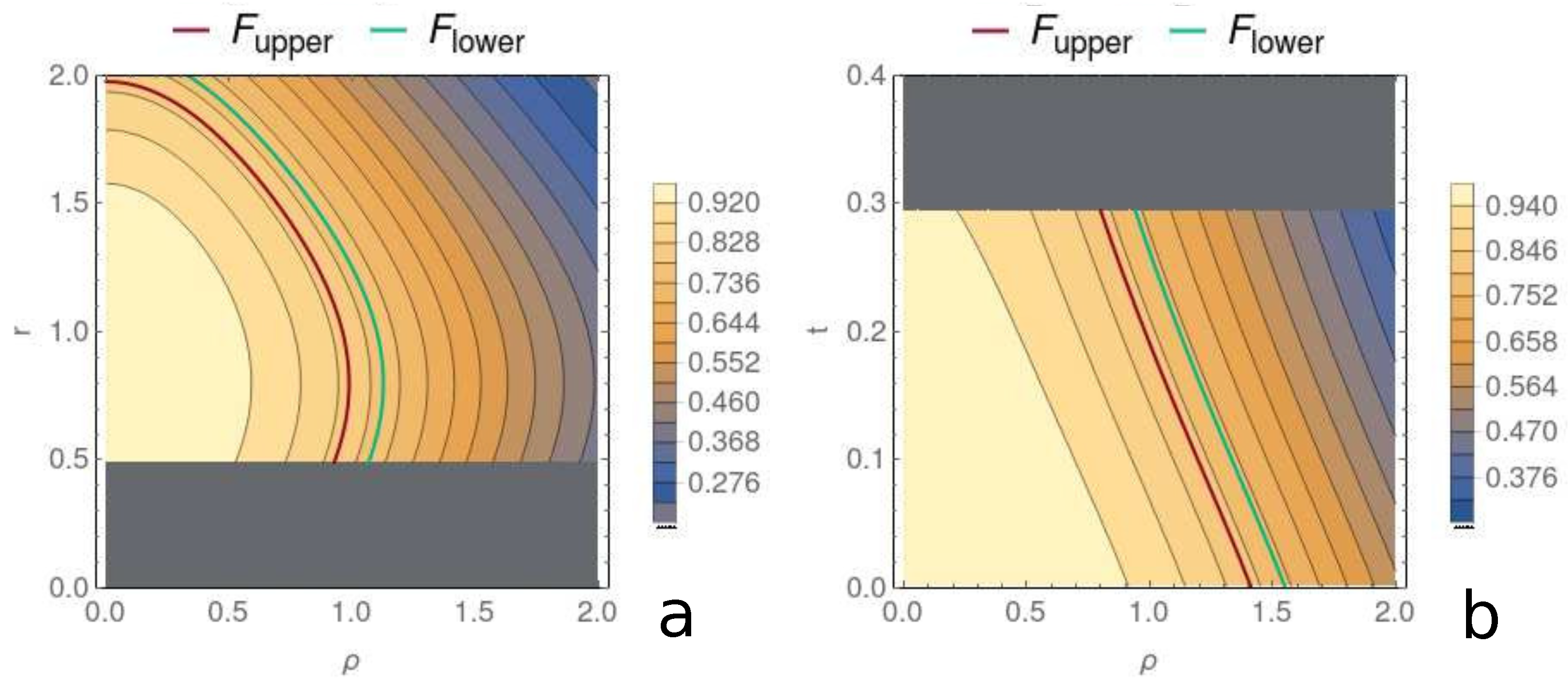

| Figure 4a | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Figure 4b | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Figure 4c | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Figure 4d | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

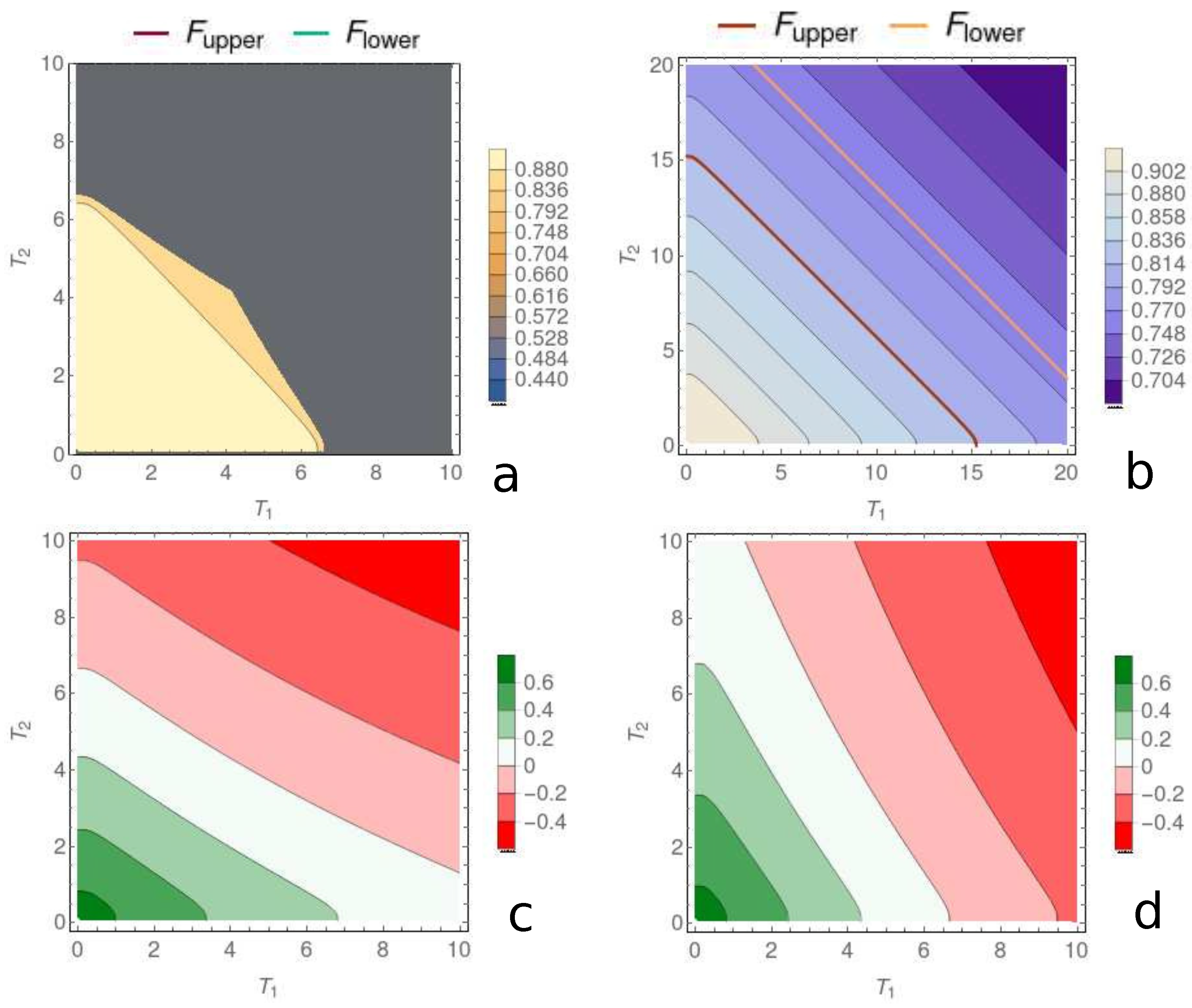

| Figure 5a | 0 | 1 | 1 | t | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Figure 5b | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | t | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Figure 6a,b | ,F | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Figure 6c,d | , | − | − | − | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Figure 7a,b | ,F | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Figure 7c,d | , | − | − | − | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zubarev, A.; Cuzminschi, M.; Isar, A. Secure Quantum Teleportation of Squeezed Thermal States. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111804

Zubarev A, Cuzminschi M, Isar A. Secure Quantum Teleportation of Squeezed Thermal States. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111804

Chicago/Turabian StyleZubarev, Alexei, Marina Cuzminschi, and Aurelian Isar. 2025. "Secure Quantum Teleportation of Squeezed Thermal States" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111804

APA StyleZubarev, A., Cuzminschi, M., & Isar, A. (2025). Secure Quantum Teleportation of Squeezed Thermal States. Symmetry, 17(11), 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111804