Hmong textile have seemingly been overlooked as objects of analysis because there may have not been a place to anchor such an inquiry. This issue focuses on the ontology of symmetry as a place from which such analysis is possible. The ontological turn therefore, is not thwarted by culture but can be in tandem with it, as symmetry a quintessential part of nature and utilized by cultures then it can bridge this oncological divide. This paper, thus, attempts to bridge this divide by exploring the symmetries of Hmong textiles. It proposes a novel perspective on studying the paj ntaub (pronounced pa’dau) by using anthropological symmetry, the gestalt theory on perception, and ethnographic analysis of the culture, meanings, and the choices in design embedded in the textiles, as well as the process of making of the paj ntaub as representations of yin and yang such as, life and death as an indispensable part to human existence. This article takes up the question of how paj ntaub work particularly within the context of the ontology and symmetry of the textiles and how art and symmetry are linked through the paj ntaub. The theories of gestalt and symmetric anthropology are discussed briefly as well as the ethnographic work on the Hmong cosmology and the paj ntaub. This paper concludes that the paj ntaub represent that existence and expresses their need to understand meta-questions such as death and evil through the constructions of their art resulting in symmetries and expression of “figure and ground” abstract imagery.

This study suggests an approach to what is known about Hmong textiles because few authors have attempted to understand why the Hmong textiles exists in the form that it does. Hopefully, this study will enable future researchers to ask even more interesting questions about an art form that has been so ubiquitous to Hmong culture but one which, for the most part, has been overlooked.

1.1. Background—A Brief Historical/Cultural Context

Some Hmong believe that the abstract symmetric designs are reminiscent of ancient writing [

1,

2]. However, without some sort of Rosetta stone, it is difficult to prove whether it was some form of writing or not. Instead of arguing if it is or is not an ancient alphabet, this paper examines what is known about the Hmong textiles or specifically

paj ntaub. The paj ntaub does communicate something. Most obvious is that it communicates ethnic regional or tribal identities [

3]. However, the paj ntaub is more than an identity marker for the Hmong. This paper suggests that by envisaging things from their perspective using the tools of gestalt theory and symmetry afforded to the researcher non-Hmong can appreciate the paj ntaub more like the Hmong who use and make paj ntaub. Notwithstanding, this paper is not about individual performativity and interpretations, nor is it about individual choices of what motifs are combined to create paj ntaub. This paper studies the material constraints on the process of constructing paj ntaub, the conventions of paj ntaub and cognitive understanding of what the paj ntaub limits and enables in artists’ choices. As a result, much more can be understood about paj ntaub.

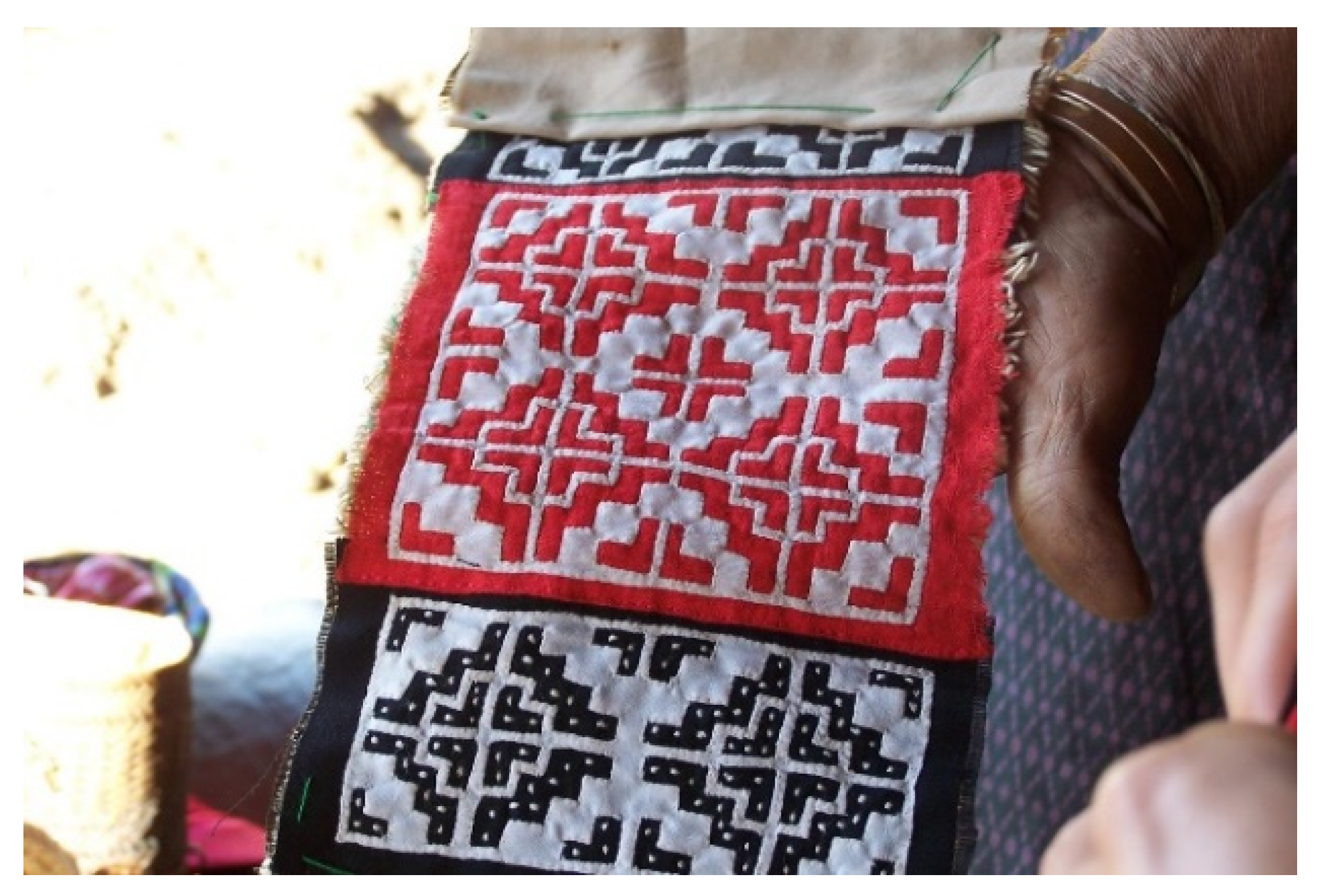

This paper results from ethnographic research conducted for the School of Design and Media at Nanyang Technical University in Singapore in 2011. The ethnographic study was part of a development project to assist artists and designers at the university to support and to develop grass roots cottage-based industries helping artisan women raise their standard of living. Initial archival research was conducted at Nanyang Technical University and the Asian Civilization Museum in Singapore. The ethnographic study took place for seven weeks in April–May 2011 with the cooperation of the Traditional Arts and Ethnological Centre in Luang Prabang, and Nam Et-Phou Louey National Park in Laos. The first half of the fieldwork was conducted in Laung Prabang for three weeks with the assistance of a translator. Interviews were conducted with artisan women associated with ethnographic center. In addition, discussions were conducted with artisan women selling their textiles in the Laung Prabang night market. The second half of the study was conducted in the village of Luhnub Nyu (pseudonym), again with a local translator. Luhnub Nyu is located near the national park in the northeast corner of Laos near the Vietnamese boarder. Participant observation and ground theory were the primary methods of data collection. Interviews were conducted with both men and women of the village after the day’s labor or with elderly women and occasional youth who stayed in the village taking care of the young children while the able adults went into the fields to cultivate the crops. Over thirty hours of recordings were made. The interviews were transcribed and were subject to content analysis. Though both young and old women in Luhnub Nyu work tirelessly in their homes, at school, and in the fields, they still found time to discuss their art and to work on their needle work. Firstly, it is important to put the textiles and the people into a cultural and historical context.

The people of this study are known by many names in Southeast Asia and China, Meo, Miao, or Mon. However, in Southeast Asia they prefer to be known as the ‘Hmong’. The Hmong have a noteworthy but tragic/heroic past. They are an ethnic group of Southern China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and Miramar who fled from aggressions of the Han Chinese from 1790–1860 and settled in the mountains of Southeast Asia [

4]. Many authors have suggested that Hmong identity is grounded in their cosmology and belief system which is transferred to younger generations primarily through oral traditions and religious practice, but also in the making of the paj ntaub (exhibits and social media refer to paj ntaub as “identity, memory and history” [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8].

After almost two centuries from their expulsion from China, the Hmong were thrusted into the cold war, or in their case the ‘hot’ Vietnam War. During the war the United States recruited them to fight what is now known as the “Secret War” (1960–1973) in Laos against the communist Pathet Lao and Vietcong as part of the CIA’s attempts to stops supplies entering Vietnam through Laos. Intense bombing of Laos (officially a neutral party in the war) ensued during most of the 1960s and 70s. The Hmong were consequential abandoned by their allies when the nationalist government fell, and the Americans suddenly retreated from Southeast Asia. The Pathet Lao aggressively pursued the Hmong until they ended up in Thai refugee camps, living there for several decades. Even with such disruptions, they maintained their textile practices and developed new ones [

9].

There are two broad categories of Hmong textiles. The first very old style discussed in this paper is the

paj ntaub which translates in English to flower cloths. The Hmong are also known for the textiles,

paj ntaub dab neej which literally translates to flower cloths of the people, customs, and traditions [

9,

10,

11]. The

paj ntaub dab neej are referred to as story cloth in English. The two style are contextually very different.

Paj ntaub dab neej cloths were first produced in the refugee camps during the war to deal with the monotony of life in the camps and to generate income for the refugees. Technically simpler men would trace figure and scenes of daily life, their sojourn to Thailand, and the bombing of their villages. Then women would use applique and needle point to fill in the sketches with color and form) than the paj ntaub, both men and women participated in its creation [

9]. Story cloths are representational depictions of daily life, Hmong tales, legends, and myths [

9,

12]. In contrast, the paj ntaub is made up of combinations of abstract but conventionalized non-representational geometric shapes. The geometric and symmetric designs are used to decorate sailor collars worn on the backs of women, decorate children’s hats and baby carries, and celebratory clothes used in Hmong New Year’s celebrations, wedding, and funerals.

The Hmong are made up of several major clans, which are differentiated by their dress and spoken dialect of the Hmong language. The clans are relatively endogamous. In Laos, the majority of Hmong are Blue/Green Hmong, and White Hmong. Other clans are the Red Hmong, Black Hmong, and Flower Hmong. There are many villages in China which had been identified as Miao, Chinese for Hmong. The debate of whether they are Hmong or not is beyond the focus of this paper. The people of Luhnub Nyu are White Hmong, or

Hmoob Dauw. Luhnub Nyu is one of many Hmong villages in Nam Et-Phou Louey District. Luhnub Nyu is at an elevation of about 600 m and boarders a nature reserve. As a result, swidden agricultural practices have been severely restricted. According to officials at the nature reserve, people of Luhnub Nyu now have one of the poorest diets in Laos. Luhnub Nyu is a village of approximately 30 households and was re-established in eastern Laos in 1992. The people of Luhnub Nyu fled to refugee camps in Thailand during the bombing campaign of the Secret War. The United States dropped over two million tons of ordinances of over 58,000 bombing missions on Laos from 1964 to 1973, ‘The Secret War in Laos.’ [

13]. The village has three headmen. In contemporary Laos, a headman is not a headman in the anthropological sense. He is actually a state political position which is paid and directly tied to the local/national one-party government. Village party members are elected through local elections to become headmen. The villages are planned into three organizational units under the responsibility of a particular headman (personal communication).

Residence patterns are generally patrilocal. Sons live under one roof with their parents and their wives. In Luhnub Nyu, the houses are situated into agnatic groupings so that male cousins will live adjacent to one another [

8]. As observed by Tapp [

8], those houses with cement floors and more modern constructions received some remittances from relatives overseas. My hosts have a house with a cement floor, a television, and a DVD player as well as an unpacked refrigerator waiting for an electrical system to be able to support it.

1.2. Gestalt Psychology

To better understand the significance of the paj ntaub textiles, it is important to understand how the paj ntaub relates to gestalt theory and the perception of these designs, symmetry and how the paj ntaub are constructed, and when and where the cloth are used and if it possibly has a relationship to the supernatural. Gestalt psychology examines how humans envision parts as a whole putting bits and pieces together to form a coherent image [

14]. Understanding gestalt theory is probably more important for the non-Hmong observer to translate their cloths than for the Hmong themselves because they take it for granted that the paj ntaub is perceived. As shall be illustrated later in this paper, how the Hmong creator sees her textiles is because the perception of motifs is closely linked to how she makes the paj ntaub. It is consequential that their textiles are perceived through its component parts but also as a whole.

The Hmong girls are taught to sew paj ntaub from a very early age which suggests how the Hmong women’s brains may develop with a keener sense of perception. Further studies may show that women who create Hmong paj ntaub may have a more acute awareness of ‘figure and ground’ since they have been working with them from a very young age. For a non-Hmong however, it takes many hours to train the ‘eye/brain’ to see the less apparent designs.

That being said, the word for “form” in German, is gestalt. The gestalt theorists maintain that perception is to make sense of forms in the worlds by organizing their elements. The eye sees light and dark, figures and shapes. The brain then translates these abstractions into some sort of coherent idea through which the brain can make sense of the world [

15]. The gestalt theorists have developed different categories of form or elements:

Continuation, which occurs when the eye is compelled to move through one object and continue to another object;

Similarity, which occurs when objects look similar to one another. The viewer will perceive them as a group or pattern. These can be similarities in color, shape, texture, or other design elements;

Closure, which occurs when an element is incomplete, or a space is not totally enclosed;

Proximity, which occurs when elements are placed close to one another. The position of the elements helps to portray a relationship between the separate parts;

Symmetry, which are elements that are symmetrical to each other tend to be perceived as a unified group;

Figure and ground, where the eye differentiates an object from its surrounding area. A form, or shape is perceived as figure, while the surrounding area is perceived as ground [

14,

16].

To perceive the paj ntaub one uses similarity, proximity, symmetry and, most importantly, figure and ground. To better comprehend figure and ground, it is important to understand how the observer perceives a border or a background. It becomes interesting when the border/background is ambiguous.

Depth is the perceiving of something on top of something else the observer forms images.

Surroundedness is where an image is surrounded by another as a result one sees a small object on a background or a foreground with a window. Thus, a small object is imagined as a background.

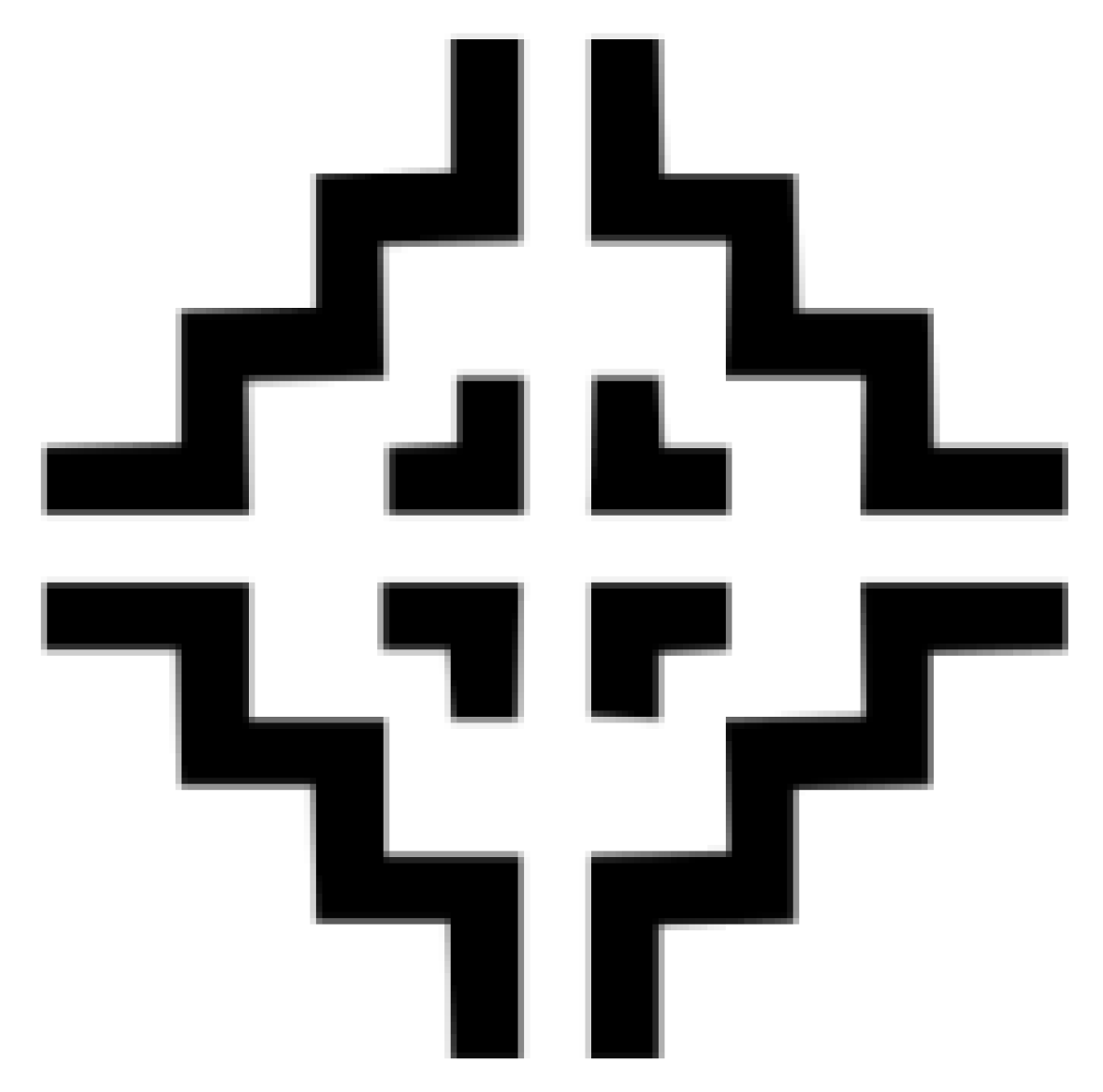

Symmetry Regions that exhibit symmetry are more likely to be figures than nonsymmetrical regions.

Convexity is when regions with convex borders are more likely to be perceived as figures than are regions with concave borders.

Meaningfulness is a visual system which assesses the meaningfulness of shape-recognizing it and assigning border to determine figure/ground perception.

Simplicity is the visual system which interprets an image in the simplest way it can be [

14,

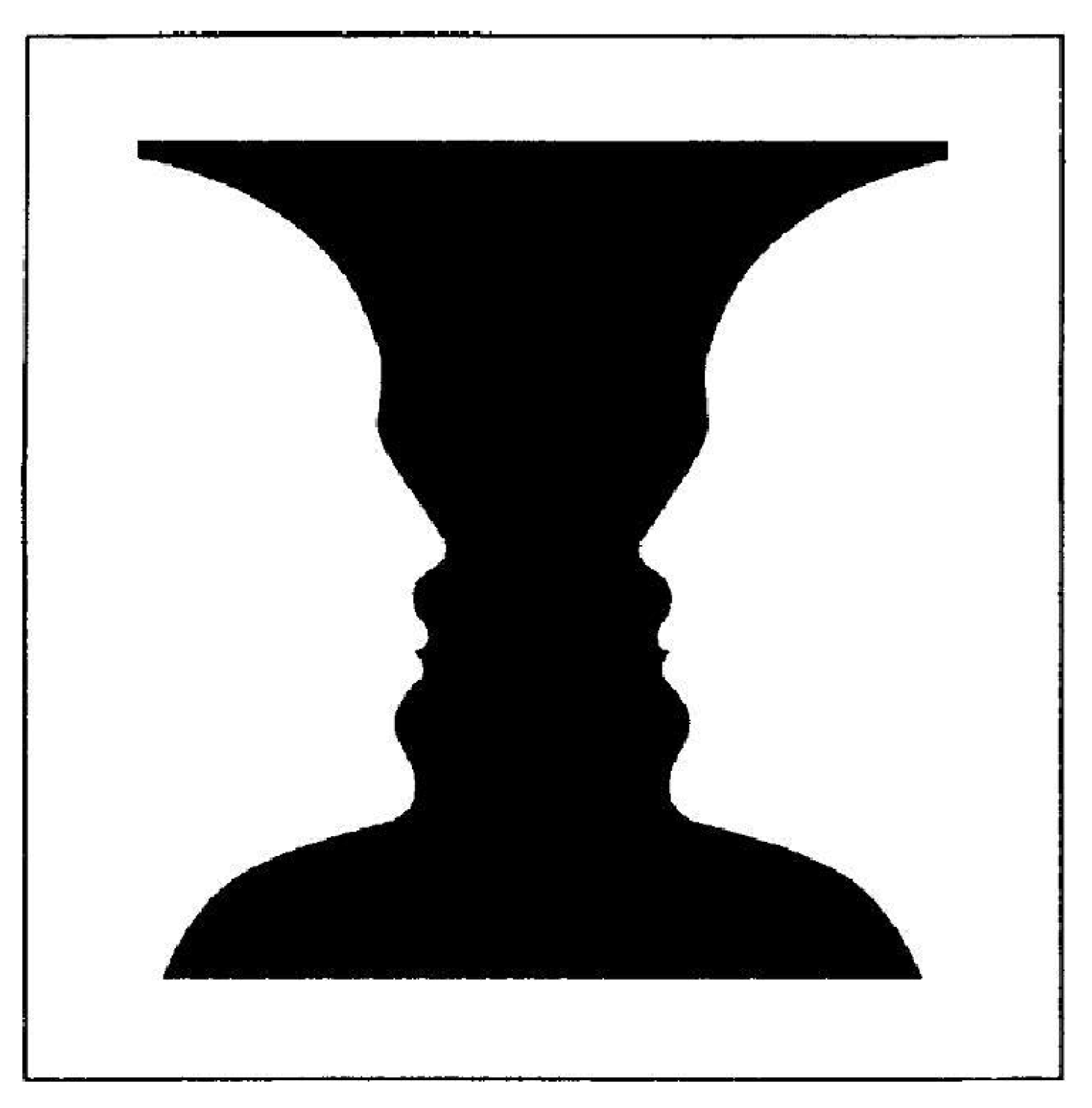

16]. In the classic example of Rubin’s vase/two faces, is it a vase on a dark background or is it two faces on a light background (see

Figure 1)? Assessing borders in the paj ntaub allows the observer to know where the ambiguous foreground and background create two distinct images.

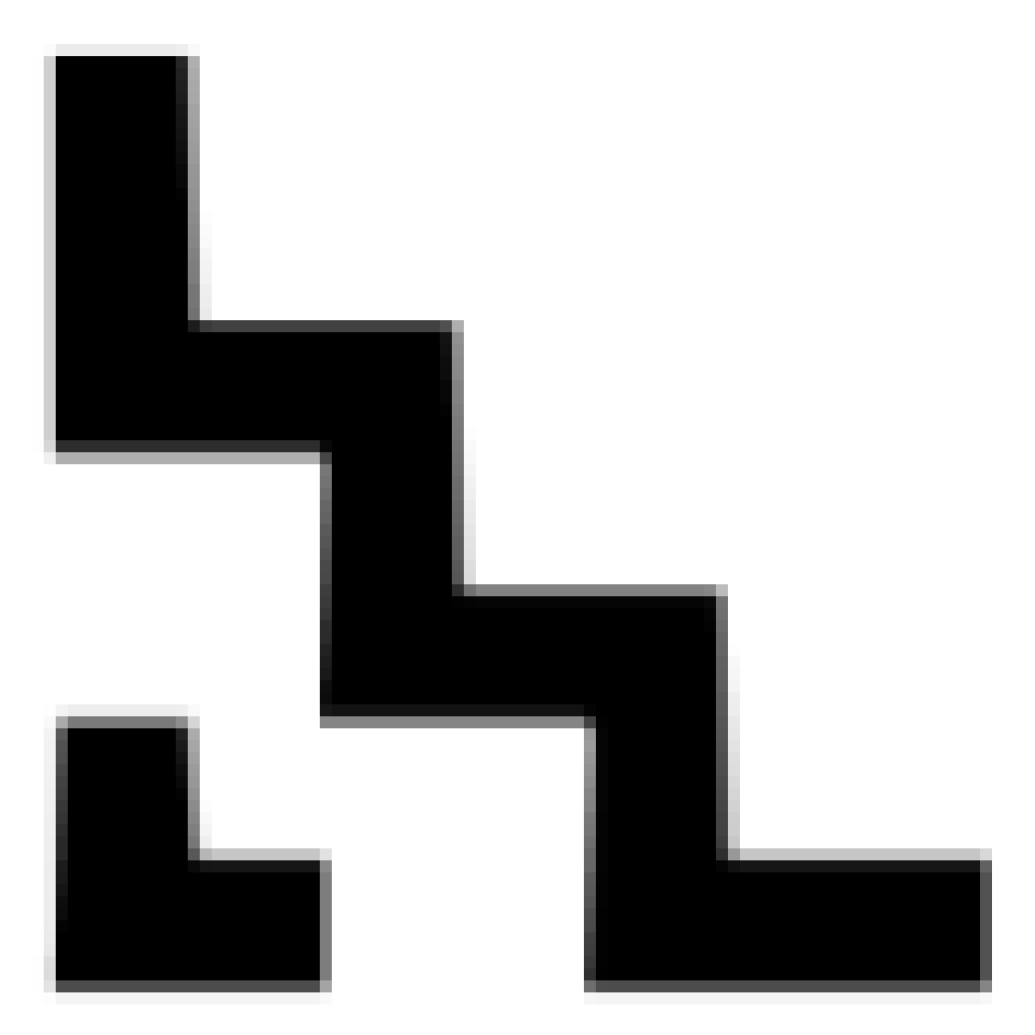

There are several principles when assigning borders. The paj ntaub motifs are perceived as having depth to which the mind of the observer sees simple patters made from designs in their ‘proximity’ and ‘similarity’ and finally these motifs have names, in other words are ‘meaningful’ which means some of the names may be arbitrary as Cohn [

18] suggests but others have cosmological significance. Either way, they are identifiable.

Levi-Strauss [

19] in an unusual way concurs with gestalt theory and may be applied to paj ntaub because both Levi-Strauss and the gestaltists believe the mind operates under particular mental structure. So, instead of rejecting the gestalt theory as merely a Western perception of the world, its ideas maybe tested within the context of Hmong ontologies envisaging paj ntaub in a way that has never been understood before. An outsider can better comprehend the paj ntaub if s/he has an understanding of gestalt theory because the Hmong in the construction and choice of motifs-design, the artisan already may intuitively use gestalt theory’s perceptions of their world.

Symmetry and possibly Hmong cosmology are also embedded into Hmong paj ntaub. Here again understanding how symmetric designs work is something that a non-Hmong needs to understand Hmong symmetry. The creator of the textiles again comprehends the symmetry embedded in their work because of how it is made. As suggested in the introduction of this issue, there is an ontology of symmetry, but how can the outsider cognitively understand what the ‘natives’ already perceive? Thus, the Hmong textiles is not simply a marker of identity. The abstract geometric symmetries may have greater ontological complexities. Before Hmong textiles are examined it is important to put the Hmong art into context. As is the focus of this issue it is important to understand Hmong textiles’ symmetric designs and the perception of the symmetric designs and put the designs and objects into a cultural context.