Abstract

Medical data usually have missing values; hence, imputation methods have become an important issue. In previous studies, many imputation methods based on variable data had a multivariate normal distribution, such as expectation-maximization and regression-based imputation. These assumptions may lead to deviations in the results, which sometimes create a bottleneck. In addition, directly deleting instances with missing values may have several problems, such as losing important data, producing invalid research samples, and leading to research deviations. Therefore, this study proposed a safe-region imputation method for handling medical data with missing values; we also built a medical prediction model and compared the removed missing values with imputation methods in terms of the generated rules, accuracy, and AUC. First, this study used the kNN imputation, multiple imputation, and the proposed imputation to impute the missing data and then applied four attribute selection methods to select the important attributes. Then, we used the decision tree (C4.5), random forest, REP tree, and LMT classifier to generate the rules, accuracy, and AUC for comparison. Because there were four datasets with imbalanced classes (asymmetric classes), the AUC was an important criterion. In the experiment, we collected four open medical datasets from UCI and one international stroke trial dataset. The results show that the proposed safe-region imputation is better than the listing imputation methods and after imputing offers better results than directly deleting instances with missing values in the number of rules, accuracy, and AUC. These results will provide a reference for medical stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Due to the advancement of medical knowledge and technology, the life-span of human beings has significantly improved, and health has become increasingly important for everyone. The aging population led to 56.9 million deaths worldwide in 2016, among which the top ten diseases caused more than 54% of deaths [1]. Ischemic heart disease and stroke have been the leading causes of death worldwide for the past 15 years, killing 15.2 million in 2016.

The rapid development of information technology produces increasingly more data, so determining how to effectively use these data and turn them into valuable information is crucial. The effective use of a medical database allows one to find the death factors and rules of patients based on past data and information. When similar symptoms (factors) occur at the time of medical treatment, medical staff can utilize these factors (rules) to make the best medical decisions for the patient immediately. Data mining is usually applied in medical research as data mining and knowledge discovery can find medical rules and diagnose of disease to provide a decision reference for medical stakeholders.

Medical data often contains many missing values (MVs), which makes analysis difficult for researchers who want to build a model using those data. Medical data have MVs for various reasons; for example, due to personal privacy, it is often difficult to collect complete data. Although hospital systems are able to capture the overall data measurement results, some patient data will remain missing from the database. Another reason for this sparsity is that doctors usually write important diagnostic information in a free text format, which is not converted into a machine-readable format. These shortcomings make it difficult for algorithms to capture patterns in medical datasets.

Thus far, there is no correct way to handle all problems of missing values. It is difficult to provide a general solution, as different types of problems have the different solutions for data imputation. The simplest way to deal with this problem is to remove the observations with MVs; however, this will lose data points with valuable information. A better strategy is to estimate the missing values-in other words, estimating the MVs from the existing parts of the data. From Little and Rubin [2], there are three main types of missing data: Missing completely at random (MCAR), Missing at random (MAR), and Not missing at random (NMAR). In MAR and MCAR, it is feasible to remove the data with MVs by relying on their occurrences, while in MNAR, removing observations with MVs can produce a bias in the model. Therefore, we must be careful before removing observations.

Since medical data often have MVs, missing value estimations could be an effective method to improve upon biased research results. Therefore, this paper proposes a new imputation method, which is a safe-region imputation method, to impute MVs. Overall, this paper offers four objectives and contributions, as follows:

- (1)

- Developing a safe-region imputation method for handling MVs, and comparing its performance with the k-nearest neighbors and multiple imputations via chained equations imputation methods [3];

- (2)

- Using four attribute selection methods to select the important attributes, and then integrating the selected attributes of the four attribute selection methods;

- (3)

- Experimentally collecting four open medical datasets from UCI and one international stroke trial dataset.

- (4)

- Comparing the generated rules and accuracy before and after imputation; and providing the results to medical stakeholders as a reference.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the related work is presenting, including medical data imputation, attribute selection, imputation methods, and related classifiers. Section 3 introduces the concept and algorithm of the proposed method. The experimental environment, data, results and comparisons, and findings and discussions are presented in Section 4. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

2. Related Work

This section introduces the related literature, including medical data imputation, attribute selection, imputation methods, and related classifiers.

2.1. Medical Data Imputation

Medical data imputation is a very popular research area [4,5,6] because data with MVs will not only destroy the integrity of information but also lead to deviations in data mining and analysis. Therefore, it is necessary to realize the estimation of MVs in the data preprocessing stage to reduce the possibility of data loss due to human errors and operations. Estimating medical MVs requires statistical methods and knowledge of data mining. When mining medical data to extract knowledge, it is necessary to handle MVs to obtain a better result. Although there are many imputation methods, most cannot provide better results. One of the simplest (and default) methods for dealing with MVs is to delete records with MVs. Removing incomplete medical records is only applicable when the number of such incomplete records is small, and the pattern is not known.

Medical data are essential for both patients and physicians, as physicians refer to the patient’s medical records to diagnose possible diseases, and the patients expect the physician to diagnose the relevant diseases and restore his or her health correctly. If there are MVs or mistakes in the medical records due to the the physician providing a misdiagnosis, it is challenging to obtain complete patient information; medical stakeholders may, therefore, not have complete records when logging in to the medical records system. Based on ethical issues for electronic health records [7], patient information should only be disclosed to others with patient permission or legal permission. Therefore, medical records involve individual privacy, and patients may be reluctant to provide relevant information, such as their occupation, work unit, and marital status. In summary, MVs increase the difficulty of analysis and may lead to deviations in results. Therefore, medical data imputation is now commonly used in medical research because imputation methods can obtain more complete data.

Medical data are applied to extract knowledge and generate patterns. The first problem to consider is the problem of MVs. Medical data imputation is one of the methods for handling MVs. Many imputation techniques are used in the medical field, such as regression imputation and multiple imputation. There are many references for medical data imputation. Purwar and Singh [5] applied 11 imputation methods to estimate MVs; then they used k-means clustering to delete the incorrectly classified instances and applied multilayer perception to classify medical data. Bania and Halder [6] applied kNN imputation to impute medical data and proposed an ensemble attribute selection based on a rough set. Sterne et al. [4] applied multiple imputation in epidemic and clinical studies. Furthermore, Yelipe et al. [8] proposed an improved imputation approach called imputation based on class-based clustering.

2.2. Attribute Selection

The attribute selection method provides a way to reduce computational time, improve predictive performance, and better understand data in machine learning or pattern recognition applications [9]. Attribute selection is used to identify attributes related to certain diseases and find a discriminant to build a reduced pattern classifier for removing the irrelevant attributes. This study used four attribute selection methods to filter irrelevant attributes, which are introduced as follows.

2.2.1. Correlation attribute

The correlation Attribute (CA) evaluates all attributes related to the target class via Pearson’s correlation method, which provides a ranking of the attributes from high to low. CA considers nominal attributes based on their value, where each value serves as an indicator. CA only handles the related attributes to be involved in the data mining process. This reduces processing time and the data dimension [10]. Before classification, we apply the attribute selection algorithm to find the important attributes for reducing computational time and the data dimension. Attribute selection must first generate a subset of attributes and rank them. Generating an attribute subset is a search process used to compare a candidate attribute subset with the determined attribute subset. If the new candidate attribute subset offers better results in an evaluation, the new attribute subset is called the important attribute set. This process is repeated until the termination condition is reached.

2.2.2. Information gain

Information Gain (IG) is a measure based on the entropy of a system [11], which is based on using the IG value to filter and rank attributes. The IG value of each attribute represents its relevance to the dataset; that is, a higher IG value means that the attribute contributes more information [12]. IG evaluates the importance of an attribute by measuring the information gain, calculated with respect to the target class using the following formula:

where H represents Shannon’s entropy [13]. Shannon’s entropy is used to measure the randomness and uncertainty of the outcome of random variables. The lower the entropy is, the more predictable the outcome of the random variable will be. The entropy equation is defined as

where is the probability of the i-th class result, and k is considered to be a constant that normalizes the information unit based on the logarithm base used, where k = 1, and the logarithm is base 2.

IG(Class,Attribute) = H(Class) − H(Class|Attribute)

2.2.3. Gain ratio

The Gain Ratio (GR) is the ratio of information gain to the inherent information (used to consider the probability of each attribute value), which was proposed by Quinlan [14] to reduce the deviation of multi-value attributes by considering the numbers and sizes of branches when selecting attributes. GR evaluates the importance of an attribute by measuring the attribute’s gain ratio with respect to the class. The GR can be calculated by the following equation [15]:

where H is entropy, and the attribute with the largest gain ratio is selected as the split attribute. However, when the split information approaches 0, the ratio becomes unstable. To avoid this problem, we need a constraint: The information gain of the selected test must be large—at least as large as the average gain of all tests.

GR(Class, Attribute) = (H(Class) − H(Class|Attribute))/H(Attribute)

2.2.4. ReliefF

ReliefF is an attribute selection method proposed by Kira and Rendell [16] and is a distance-based attribute selection method. The Manhattan distance is applied to calculate weights and generates negative and positive weights in ReliefF; the negative weights then allocate redundant attributes in ReliefF. The relief-based attribute selection method the Euclidean distance, but ReliefF uses Manhattan distance to generate weights. The purpose of ReliefF is to find the correlation and consistency present in the attributes of the dataset and identify important attributes, which can solve the problem of proximity to samples of the same class and distance from a different class. ReliefF can classify more than two classes and regression problems to improve the problem of relief in the classification [17].

2.3. Imputation Methods

Handling missing data is a very important task in data preprocessing, and the performance of a data mining model is adversely affected when incomplete data are directly removed [18]. Therefore, understanding the reasons why data have missing values can determine the strategy needed to estimate the missing value. Nonetheless, it remains a difficult task to attribute all missing data in the dataset to a single missing data mechanism because missing data do not only conform to a single missing mechanism. In general, two broad methods exist for handling missing values. The simplest method involves discarding data with MVs, which is easy to implement and can accelerate the process of analysis. Directly removing the data with missing values will reduce the size of the dataset and the computational requirements, but it will also affect the accuracy of the model [2]. The other method is the data retention method, which can avoid deleting data points and reduce the number of observations. There are many different data retention methods, ranging from very simple to quite complex, all of which replace MVs with estimates. All these methods are categorized under the imputation umbrella.

Data imputation methods are of two main types: statistics-based methods and data mining-based methods. The simplest imputation methods based on statistics are conventional imputation techniques [19], such as mean imputation and class mean imputation. Linear regression [20] and Expectation-Maximization [21] are the most common statistics-based imputation methods, but they assume that the variable data have a multivariate normal distribution. Machine learning is the most popular method for estimating MVs in data mining-based methods. Applying data mining to impute missing values can extract useful information from the original dataset to build a prediction model. Moreover, many algorithms based on data mining have been proposed [22], such as k nearest neighbor (kNN), neural networks, decision trees, random forest, and kernel-based imputation. This study will use kNN and multiple imputation as a comparison against the proposed imputation method. These two imputation methods are introduced as follows.

2.3.1. kNN Imputation

The kNN algorithm [23] was first proposed by Cover and Hart in 1967. kNN is a lazy learning algorithm; it does not use a pre-established model before classifying the data. To overcome the shortcomings of the traditional kNN algorithm, many scholars have proposed improved methods from different perspectives. For example, weighted KNN adds weight to the distance of each point. Hence, a closer point can obtain a greater weight. In handling MVs, kNN imputation was first presented by Batista and Monard [24], who estimated MVs by finding the k nearest neighbors to the observation with MVs and then imputing them based on the non-missing values in the neighbors. To deal with heterogeneous data, Zhang [25] proposed a gray kNN imputation method to estimate the MVs iteratively.

2.3.2. Multiple Imputation

Multiple imputation [26] is a simple and effective method for handling MVs. Multiple imputation reduces the uncertainty of MVs by calculating several different options (imputations). In this method, multiple versions of the same dataset are created and then combined to form the “best” estimated value. Multiple imputation based on fully conditional specifications was implemented through the Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) algorithm [27], MICE is a special multiple imputation technique. In MICE, a series of regression models is operated to estimate each variable with missing values based on other variables in the data. This means that each variable can be modeled according to its distribution—for example, binary variables fit by logistic regression and continuous variables fit by linear regression.

2.4. Classification Techniques

This section introduces four rule-based classifiers for comparing the generated rules and accuracy before and after imputation. The four rule-based classifiers include random forest, decision tree, reduced error pruning tree, and logistic model tree, as follows.

2.4.1. Random Forest

Random forest (RF) is an ensemble classifier that creates multiple decision trees and integrates them into an ensemble model [28]. RF can be used for both classification and regression tasks. RF adds a layer of randomness to bagging and uses different bootstrap data samples to construct each tree. In a standard tree, each node is branched by the best allocation among all variables. In a random forest, each node is branched using the best value in a subset of predictors randomly selected by that node [29]. Breiman [29] first introduced an appropriate random forest in a journal article; he used a procedure similar to classification and regression trees combined with random node optimization and bagging to build a forest of unrelated trees.

2.4.2. Decision Tree C4.5

Decision Tree (DT) is a supervised learning method used for classification and regression and has been identified as the baseline algorithm for prediction performance [30]. The advantage of the DT algorithm is its accurate and fast classification. The generation of DT is similar to the human thought process; hence, it is highly interpretable. DT summarizes a set of classification rules from the training data set. The selected tree will have the least conflict where the generated rule is not only very consistent with the training data but also offers good prediction performance on test data. Decision tree C4.5 [31] and its predecessor ID3 [14] are algorithms for summarizing training data in the form of decision trees, C4.5 is a good algorithm to handle irrelevant and redundant information. A smaller branch is preferred to make C4.5 easier to understand. The path from a leaf node to a leaf is called a classification rule.

2.4.3. Reduced Error Pruning Tree

The Reduced Error Pruning (REP) Tree combines reduced error pruning (REP) with the decision tree (DT) to split and prune the structure of the tree [32,33]. The REP tree uses information gain as a branch criterion to build a decision and regression tree and then prunes it using reduced error pruning [34]. Using the “reducing error pruning method” reduces the complexity of the decision tree model, thereby decreasing the number of errors caused by variance. Due to their simple configuration, decision trees are a very popular method for classifying problems. There are two methods for pruning decision trees: One is pre-pruning, and the other is post-pruning. From a comparison of the two pruning methods, it is clear that the trees that produce pre-pruning are fast, while post-pruning is more successful in generating trees [35].

2.4.4. Logistic Model Tree

The Logical Model Tree (LMT) is a popular model tree algorithm [36] that combines decision tree and linear logistic regression. LMT aims to achieve high predictability and interpretability by combining two algorithms into a model tree and has been widely used in the medical and health sciences research fields [37]. The logistic variant of information gain is used for the branching node, and the LogitBoost algorithm [36] is applied to generate a linear regression at each node in the tree. Classification and regression tree can be used to prune the tree [38], and linear logistic regression can be used to calculate the posterior probability of leaf nodes in the LMT model [36].

3. Proposed Method

In the age of information technology, it is essential for medical personnel to have complete data to diagnose patients’ diseases correctly. Any bias or incorrect information will have a significant impact on medical personnel and patients, and misdiagnosis may lead to a more severe illness. Medical data often have MVs due to patients who are reluctant to disclose their private data or medical staff who do not record complete data. Therefore, handling data with MVs is an important issue in medical research. There are currently many imputation methods for this problem, but many imputation methods based on variable data have a multivariate normal distribution, such as expectation-maximization and regression-based interpolation. These assumptions may cause deviations in the results and sometimes yield a bottleneck. In addition, directly deleting instances with MVs may lead to some problems, such as losing important data, generating invalid research samples, and creating a research bias.

In a previous paper [39], we used Sarkar’s weighted distance [40] and the adaptive threshold to achieve optimal imputation, as Sarkar’s weighted distance does not need to know the k value of WKNN. Therefore, this study proposes a safe-region imputation method for processing medical data with MVs. This newly proposed imputation method only imputes the data points of the safe and boundary area, while the data points in sparse and outlier areas will be discarded. We use kNN, where k = 5, to illustrate the proposed safe-region imputation method as follows.

- (1)

- Identifying data the point area

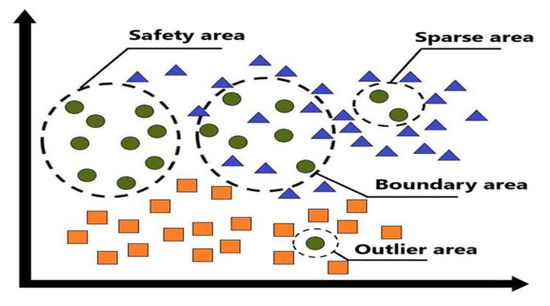

All data points will be identified based on four different areas (the safety, boundary, sparse, and outlier area) according to the criteria of area identification, as shown in Table 1. For each data point, the nearest five reference points are found, and the function cn(e) is used to represent the number of data points in the nearest neighbors of the five reference points, where e indicates that the labels have the same class. In addition, let the function cn(i) be the class label without consideration, which represents the number of data points of the nearest neighbor among the five reference points for each data point, where i represents the i-th data point. The concept of the proposed safe-region imputation method can be expressed by three different label data presented in four different areas (the safety, boundary, sparse, and outlier area), as shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Criteria of area identification.

Figure 1.

Three different label data presented in four different areas.

- (2)

- Imputing the missing value

Imputing data points with MV determines which area the MV is in. If it is in the safe area, we use kNN (k = 5 or k = 4) for imputation; in the boundary area, we use kNN (k = 3 or k = 2) to impute the MV. Otherwise, if the data point with the MV is in the sparse and outlier area, we delete the data point with the MV directly.

The kNN imputation can be briefly described as follows: two observations with the closest distance will have the closest relationship. Therefore, if an observation has an MV, we can calculate the distance from all the data in the dataset, and then the nearest five (k = 5) data points can found. In this way, the MVs are replaced by the average of the five data points.

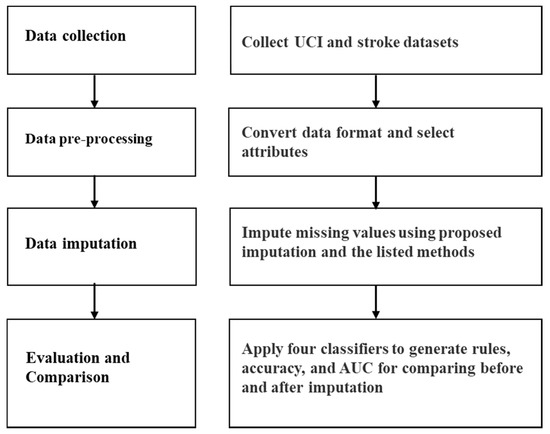

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed imputation method, we use kNN and multiple imputations to compare the results with the proposed method when handling MVs. In addition, this study used four rule-based classifiers to generate the rules, accuracy, and AUC for comparison before and after imputation. To easily understand the proposed method, we proposed a computational procedure including data collection, data preprocessing, imputation, classification and evaluation, as shown in Figure 2. The detailed steps are described in the following.

Figure 2.

The proposed computational procedure.

Step 1 Data collection

This step collected four UCI medical datasets with MVs from the UCI machine learning repository [41]. The other stroke dataset [42] is a practical medical dataset. All five datasets have missing values, and the number of attributes is greater than 10 in each dataset. The four UCI medical datasets are diabetes, audiology, thyroid disease, and breast cancer datasets; the stroke dataset was a real international stroke trial dataset [42] from the International Stroke Trial Group. A relevant description of the collected five datasets is introduced in the experimental datasets of Section 4.2.

Step 2 Data pre-processing

All collected medical datasets in this study include MVs. Before data imputation, data pre-processing must be performed.

First, the value of the class attribute is changed from a numerical to nominal (symbolical) attribute, and the class of multiple columns is merged into a new class attribute. Then, we convert all datasets into programming formats for implementing the experiments. After completing part of the attribute processing, we can conduct the attribute selection.

Second, the four attribute selection methods are applied to select the important attributes (the correlation attribute, information gain, gain ratio, and ReliefF attribute selection methods). The four attribute selection methods are used to select the important attributes and rank values, and then the rankings of the four attribute selection methods are integrated by the Condorcet ranking method [43]. After re-ranking the sum of the rank (the attribute ranking of the four attribute selection methods), we deleted the non-significant attributes based on the criterion that a correlation coefficient <0.028 is not statistically significant when the degree of freedom is 5000 at a significance significant of level 0.05 [44]. Furthermore, the number of selected attributes in the information gain and gain ratio is always less than the correlation and ReliefF attribute selection methods. We use the breast cancer dataset as an example. The integrated four attribute selection methods and their orderings are listed in Table 4 of Section 4.

Step 3 Imputation missing values

This step applies the proposed safe-region imputation method to estimate medical data with MVs. Here all data points will be assigned to the four different areas (the safety, boundary, sparse, and outlier area), as shown in Table 1. This study only imputes the data points of the safe and boundary area, while the data points in the sparse and outlier areas are discarded. In the safe area, we use kNN (k = 5 or k = 4) for imputation; in the boundary area, we use kNN (k = 3 or k = 2) to impute the missing value. The proposed safe-region imputation algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 safe-region imputation |

| c_ins: complete instance, i_ins: incomplete instance, k: the k nearest points of dataset, and new_ins: imputed instance. # calculate the minimal distance for ith in c_ins: for jth in c_ins: if ith != jth then dis[ith] = distance_complete(c_ins[ith], c_ins[jth]) set top_dis[k] as top k distance array; top_dis = get_shortest(dis, k) # get the k minimal distance points # impute missing value set min_dis as min distance variable set min_index as min distance data point missTh = 0.05 failTh = 0 for ith in i_ins: for jth in top_dis: i_dis = distance_incomplete(i_ins[ith], c_ins[jth]) if i_dis < min_dis or min_dis is null then min_dis = i_dis min_index = jth for th in 0.01 to 3.00 step 0.01 for ath in len(i_ins.arrt): for ith in i_ins: if i_ins[ith].attr[ath] is missing then/the attribute a is a missing value in the ith instance set score = 0 for jth in top_dis: if top_dis[jth].attr[ath] < th then score++ if score == 0 then failTh++ else for s in score: new_val = new_val + c_ins[top_dis[s]].attr(ath) new_val = new_val/s new_ins[ith].attr(ath) = new_val else new_ins[ith].attr(ath) = i_ins[ith].attr(ath) |

Step 4 Evaluation and comparison

Evaluation is a standard way to measure the effectiveness of a model. After imputation of the MVs, this study applied decision tree, random forest, REP tree, and LMT classifiers to generate the rules and confusion matrix. Based on the confusion matrix, we can calculate the accuracy and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). This study uses the AUC because the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) has diagnostic abilities in imbalanced classes (asymmetric classes) and can differentiate between positive detection rates and false alarm rates. Moreover, the AUC is a measure of discriminative strength between these two rates without considering misclassification costs or class prior probabilities [45]. The classification results were calculated using the confusion matrix [46]. The accuracy is defined as follows:

where tp is a true positive, fp denotes a false positive, fn represents a false negative, and tn is a true negative.

Accuracy = [(tp + tn)/(tp + fn + fp + tn)] × 100

We repeated the experiment 100 times and randomly sampled each dataset based on 66% training data and 34% testing data to implement the experiments. Furthermore, this study used the generated rules, accuracy, and AUC to compare the results after imputation with those before imputation; we also compare the selected attributes followed by imputation and removing MVs.

4. Experiment and Results

This section introduces the experimental environment and datasets and then presents the experimental results, comparisons, and findings.

4.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter

The experimental environment was a PC with an Intel i7-7700 3.6 GHz CPU running the Windows 10 operating system. The collected five datasets had MVs and different missing degrees. To compare the proposed imputation method with kNN and multiple imputation methods, this study uses decision tree, REP tree, and LMT classifiers to calculate the accuracy and AUC. The parameters of the four classifiers and three imputation methods are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter settings of the three imputation methods and four classifiers.

4.2. Experimental Datasets

Based on the dataset with MVs, the different missing degrees, and the different numbers of attributes and instances, this study collected four UCI datasets and a real stroke dataset to compare the proposed imputation with the listing methods. Table 3 outlines the number of classes, the number of attributes, the number of instances, the number of MVs, and the balanced class for the five datasets. As shown in Table 3, the collected four UCI datasets feature imbalanced classes (asymmetric classes); only the stroke dataset is a balanced class. The five datasets are briefly described as follows.

Table 3.

Dataset summary.

- (1)

- Diabetes: The diabetes dataset is from the 130-American Hospital and spans 10 years (1999–2008); this dataset includes 50 attributes (including one class attribute) and 101766 records with 2273 MVs. The dataset is divided into factors related to the readmission of diabetic patients and factors related to diabetic patients [47].

- (2)

- Audiology: This is the standardized version of the original audiology dataset donated by Ross Quinlan and mainly studies data on the types of hearing disorders in patients with hearing impairment. This dataset has 69 attributes (including one class attribute) and 200 records with 291 MVs [48].

- (3)

- Thyroid disease: This dataset is from Ross Quinlan, Garavan Institute in Sydney, Australia [14]. This study used 2800 instances with 28 attributes (including one class attribute) and 1756 MVs as an experimental dataset.

- (4)

- Breast Cancer: Wolberg, Street, and Mangasarian [49] created the original breast cancer dataset (Wisconsin). The numerical attributes are calculated from the digitized images of the fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of breast masses and involve nine numerical attributes (excluding the ID attribute) for calculating each nucleus. Hence, this study applied nine numerical attributes and one class attribute with 699 records and 16 MVs as an experimental dataset.

- (5)

- Stroke Disease: This dataset is from the international stroke trial database [42], which emerged from the largest randomized trial of acute stroke in the history of patients. The original dataset has 112 attributes and 19435 instances. This study used the dataset to predict stroke deaths; hence, we deleted some irrelevant attributes and instances of living patients and then created two class labels (death from stroke and death from other causes). Ultimately, the experimental dataset had 69 attributes and 4239 instances with 6578 MVs.

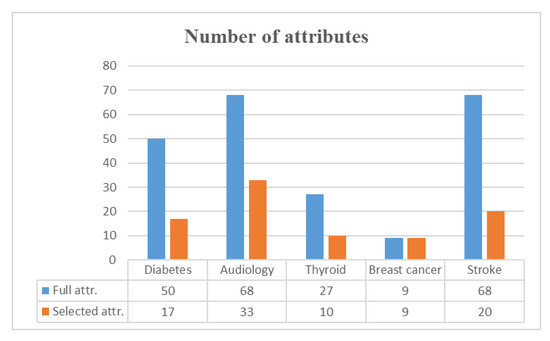

4.3. Results of Attribute Selection

This study applied the Condorcet ranking method [43] to integrate the selected attributes of four attribute selection methods. We use the breast cancer dataset as an example. The original breast cancer (Wisconsin) dataset contains nine numerical attributes (excluding the ID attribute) with 699 records and 16 MVs. First, the four attribute selection methods were used to generate important attributes and weight values; the results are shown in Table 4. Second, we ranked the ordering of the selected attributes based on the weight values for each attribute selection method and then summed the four rankings to re-rank the ordering, as shown in the last column of Table 4. Lastly, we determined whether the weight value of each attribute selection method was significant (e.g., lower weight than 0.423 in correlation is statistically significant). Hence, no attribute was discarded, and nine attributes remained. The numbers of attributes among the full and selected attributes in each dataset after integrating the four attribute selection methods are shown in Figure 3. The number of attributes in most datasets was reduced by half except for the breast cancer dataset.

Table 4.

Results of integrating the four attribute selection methods for breast cancer dataset.

Figure 3.

Results of the selected attributes.

4.4. Imputation Results and Comparisons

We use four classifiers (Decision Tree, Random Forest, REP Tree, and LMT) to generate the rules, accuracy, and AUC to compare the results after imputation with those before multiple imputation using kNN, where the results before imputation are used to remove MVs. Furthermore, after selecting the attributes, we also compare imputation with the removal of MVs. These comparisons are presented in the following.

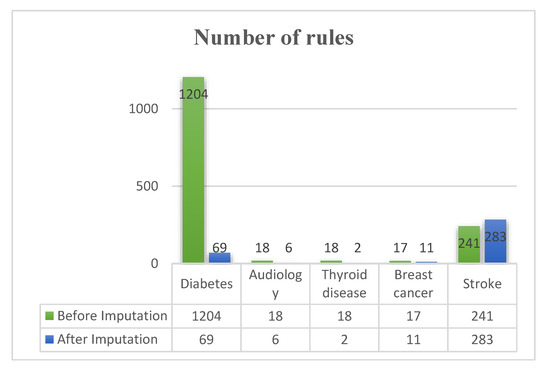

- (1)

- Comparison of before and after imputation

After imputing the MVs of the five datasets using the proposed safe-region, kNN, and multiple imputation techniques, we use decision tree, random forest, REP tree, and LMT classifiers to generate the results for before and after imputation based on the criteria of the number of rules, accuracy, and AUC, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6. In terms of accuracy, Table 5 shows that the proposed imputation is better than removing MVs and listing imputations in five datasets except for the Thyroid disease dataset. Here, kNN imputation provides better accuracy. As shown in Table 6, the proposed imputation is better than removing MVs and listing imputations in the AUC, except for removing MVs in the audiology dataset and using kNN imputation in the thyroid disease dataset, which provided a better AUC. The proposed imputation has fewer rules than imputations done before and listing imputations, except for the stroke dataset, as shown in Figure 4, where the results after imputation are based on using the best accuracy of imputation to generate the rules. Overall, the proposed imputation is better than removing MVs and listing imputations in terms of accuracy, AUC, and the number of rules for five the datasets.

Table 5.

Comparison of before and after imputation for accuracy.

Table 6.

Comparison of before and after imputation for the AUC.

Figure 4.

Comparison of before and after imputation for the number of rules.

- (2)

- Comparing imputation with removing MVs for the selected attributes

After selecting the attributes for each dataset, we compared the three imputation methods with removing MV in terms of the accuracy and AUC. First, we applied the proposed method, kNN, and multiple imputation to impute the MVs of the five datasets, and then we used decision tree, random forest, REP tree, and LMT classifiers to generate the results of removing MVs and after imputations in terms of the accuracy and AUC, as shown in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively. Table 7 shows that the accuracy of the proposed imputation method is better than removing MVs and the listing imputations in the selected attributes of five datasets except for multiple imputation in the thyroid dataset. From Table 8, after selecting attributes, the accuracy of proposed imputation is better than removing MVs, kNN, and multiple imputation in the breast cancer and stroke datasets, but the AUC of the removed MVs is better than that of the three imputation methods in the audiology, diabetes, and thyroid datasets. In summary, the proposed imputation is better than kNN and multiple imputations in terms of accuracy and AUC for the five datasets.

Table 7.

Results of imputation after selecting the attributes for accuracy.

Table 8.

Results of imputation after selecting attributes for the AUC.

4.5. Findings and Discussion

Based on the proposed imputation and experimental comparison, there are three main findings, as follows.

- (1)

- Imputation or removing missing values

Medical data contains MVs, which represent a problem for researchers who want to analyze the data. Various reasons can yield medical data with MVs, particularly reasons related to personal privacy; hence, hospital systems still loses some patient data from their databases. Furthermore, physicians usually write important diagnostic information in a free text format, which is not converted to a machine-readable format. These shortcomings make it difficult to capture patterns in medical datasets.

As medical data containing MVs is inevitable, the simplest solution is to remove the observations with MVs. However, this will lose data points with valuable information. A better strategy is to estimate the missing value; in other words, we need to estimate those MVs from the existing part of the data.

To this end, the present, this study compared removing MVs with the proposed method, kNN, and multiple imputation; the results are shown in Table 5 and Table 6. Most of the imputation results are better than removing MVs in terms of the accuracy and AUC. Furthermore, the proposed imputation has fewer rules than removing MVs and listing imputations except for the stroke dataset, as shown in Figure 4. Hence, we suggest that a better strategy for handling medical data with MVs is to estimate the MVs.

- (2)

- Imputation after selecting attributes

Attribute selection can provide a way to shorten computational time, enhance predictive performance, and strengthen data understanding in machine learning or pattern recognition applications [9]. Attribute selection identifies attributes related to target diseases and finds a discriminant to build a reduced pattern for removing the irrelevant attributes.

This study applied the correlation attribute, information gain, gain ratio, and ReliefF attribute selection methods to select attributes. The four attribute selection methods generated the important attributes and rank values. We then integrated the rankings of the four attribute selection methods via the Condorcet ranking method [43] to remove the irrelevant attributes. After selecting the attributes for each dataset, we also compared the proposed method, kNN, and multiple imputation with removing MVs. The results are shown in Table 7 and Table 8. Overall, the proposed imputation is better than kNN and multiple imputation in terms of its accuracy and AUC for five datasets. Table 8 shows that removing MVs is better than using imputation methods in three datasets. We thus require greater precision to impute the MVs after selecting the attributes. Moreover, because the datasets are imbalanced classes (excluding the stroke dataset), the AUC is an important criterion.

- (3)

- Safe-region imputation

The proposed safe-region imputation is based on using kNN to modify the imputation method in data points with MVs. In this method, we first determine which area the MV is located in. We then use k = 5 as a description. If the data points are in the safe area, we use kNN (k = 5 or k = 4) for imputation; in the boundary area, we use kNN (k = 3 or k = 2) to impute the MV. Otherwise, if the data point with the MV is in the sparse or outlier areas, we delete the data point with the MV directly, except in kNN, which uses the average of the nearest five data points to replace the MV.

Based on the experiment, Table 5 and Table 6 show that the proposed safe-region imputation is better than kNN imputation, except for the thyroid dataset, in terms of accuracy and AUC. After selecting the attributes, the experimental results show that the proposed safe-region imputation is better than kNN imputation, except for the thyroid dataset, in terms of accuracy (Table 7). For the AUC (Table 8), the proposed safe-region imputation is better than kNN imputation except for the audiology and thyroid datasets. Overall, the proposed imputation is better than kNN imputation.

5. Conclusions and Future Research

This study proposed a safe-region imputation method and compared various listing methods. The experimental comparison showed that the proposed imputation offers better performance for the full and selected attributes. To objectively verify the performance of the proposed imputation, we conducted experiments using datasets of different medical data types, including four open medical datasets with MVs and one real stroke dataset with MVs. As shown in Table 3, the collected four UCI datasets are imbalanced classes; only the stroke dataset is a balanced class. Hence, this study used accuracy, AUC, and the number of rules to evaluate the comparative performance because the AUC has diagnostic abilities in imbalanced classes (asymmetric classes) and can differentiate between positive detection rates and false alarm rates.

For future research, we should consider privacy issues. As the patients usually do not wish to disclose their private information in the data collection stage, we can add medical records security to protect patients’ private data (personally identifiable information), such as using fog-based context-sensitive access control mechanisms [50,51,52] to deal with the privacy requirements of the associated stakeholders. Second, different types of data and imputations could be applied to extend a variety of different applications for comparison and analysis. It will also be necessary to use other classifiers and recent imputation methods to produce better and more reliable performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-H.C.; methodology, C.-H.C.; validation, S.-F.H.; formal analysis: C.-H.C.; data curation, S.-F.H.; writing—original, draft preparation, C.-H.C.; writing—review and editing, C.-H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. The Top Ten Causes of Death. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Little, R.; Rubin, D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; John Wiley and Sons Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan, T.W.; Lepkowksi, J.M.; Van Hoewyk, J.; Solenbeger, P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv. Methodol. 2001, 27, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; White, I.R.; Carlin, J.B.; Spratt, M.; Royston, P.; Kenward, M.G.; Wood, A.M.; Carpenter, J.R. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009, 338, b2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwar, A.; Singh, S.K. Hybrid prediction model with missing value imputation for medical data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 5621–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bania, R.K.; Halder, A. R-Ensembler: A greedy rough set based ensemble attribute selection algorithm with kNN imputation for classification of medical data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 184, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozair, F.F.; Jamshed, N.; Sharma, A.; Aggarwal, P. Ethical issues in electronic health records: A general overview. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2015, 6, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelipe, U.; Porika, S.; Golla, M. An efficient approach for imputation and classification of medical data values using class-based clustering of medical records. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 66, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, G.; Sahin, F. A survey on feature selection methods. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanambal, S.; Thangaraj, M.; Meenatchi, V.; Gayathri, V. Classification Algorithms with Attribute Selection: An evaluation study using WEKA. Int. J. Adv. Netw. Appl. 2018, 9, 3640–3644. [Google Scholar]

- Uğuz, H. A two-stage feature selection method for text categorization by using information gain, principal component analysis and genetic algorithm. Knowl. Based Syst. 2011, 24, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-M.; Yeh, W.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Gene selection using information gain and improved simplified swarm optimization. Neurocomputing 2016, 218, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. A note on the concept of entropy. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kamber, M.; Pei, J. Data Mining Concepts and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kira, K.; Rendell, L.A. A practical approach to feature selection. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Workshop on Machine Learning; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, F. Feature selection at the discrete limit. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Québec City, QC, Canada, 27–31 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cheliotis, M.; Gkerekos, C.; Lazakis, I.; Theotokatos, G. A novel data condition and performance hybrid imputation method for energy efficient operations of marine systems. Ocean Eng. 2019, 188, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, A.R.; van der Heijden, G.J.; Stijnen, T.; Moons, K.G. Review: A gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006, 59, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ghomrawi, H.M.K.; Mandl, L.A.; Rutledge, J.; Alexiades, M.M.; Mazumdar, M. Is there a role for expectation maximization imputation in addressing missing data in research using WOMAC questionnaire? Comparison to the standard mean approach and a tutorial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-C.; Tsai, C.-F. Missing value imputation: A review and analysis of the literature (2006–2017). Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 1487–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Hart, P.E. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.E.; Monard, M.C. An analysis of four missing data treatment methods for supervised learning. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2003, 17, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Nearest neighbor selection for iteratively kNN imputation. J. Syst. Softw. 2012, 85, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Correlation-Based Feature Selection for Machine Learning; The University of Waikato: Hamilton, New Zealand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, J.R. C4.5: Programs for Machine Learning; Morgan Kaufmann: Los Altos, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elomaa, T.; Kaariainen, M. An analysis of reduced error pruning. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2011, 15, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Prakash, I.; Singh, S.K.; Shirzadi, A.; Shahabi, H.; Bui, D.T. Landslide susceptibility modeling using Reduced Error Pruning Trees and different ensemble techniques: Hybrid machine learning approaches. Catena 2019, 175, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, S.K.; Sasikala, S. Reptree classifier for identifying link spam in web search engines. ICTACT J. Soft. Comput. 2013, 3, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Hong, H.; Li, S.; Shahabi, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Bin Ahmad, B. Flood susceptibility modelling using novel hybrid approach of reduced-error pruning trees with bagging and random subspace ensembles. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehr, N.; Hall, M.; Frank, E. Logistic Model Trees. Mach. Learn. 2005, 59, 161–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jun, C.-H. Fast incremental learning of logistic model tree using least angle regression. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 97, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.; Olshen, R.; Stone, C. Classification and Regression Trees; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.H.; Chang, J.R.; Huang, H.H. A novel weighted distance threshold method for handling medical missing values. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 122, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M. Fuzzy-rough nearest neighbor algorithms in classification. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2007, 158, 2134–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, D.; Graff, C. UCI Machine Learning Repository. School of Information and Computer Science, University of California. 2019. Available online: http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Sandercock, P.A.; Niewada, M.; Członkowska, A. The International Stroke Trial database. Trials 2011, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, M. Condorcet meets Bentham. J. Math. Econ. 2015, 59, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlf, F.J.; Sokal, R.R. Statistical Tables, 3rd ed.; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Moayedikia, A.; Ong, K.-L.; Boo, Y.L.; Yeoh, W.; Jensen, R. Feature selection for high dimensional imbalanced class data using harmony search. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2017, 57, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut, C.; Webb, G.I. Encyclopedia of Machine Learning; Springer Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strack, B.; DeShazo, J.P.; Gennings, C.; Olmo, J.L.; Ventura, S.; Cios, K.J.; Clore, J.N. Impact of HbA1c Measurement on Hospital Readmission Rates: Analysis of 70,000 Clinical Database Patient Records. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UCI. Machine Learning Repository. 2020. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Audiology+(Standardized) (accessed on 26 July 2020).

- Wolberg, W.H.; Street, W.N.; Mangasarian, O.L. Machine learning techniques to diagnose breast cancer from fine-needle aspirates. Cancer Lett. 1994, 77, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayes, A.S.M.; Kalaria, R.; Sarker, I.H.; Islam, S.; Watters, P.A.; Ng, A.; Hammoudeh, M.; Badsha, S.; Kumara, I. A Survey of Context-Aware Access Control Mechanisms for Cloud and Fog Networks: Taxonomy and Open Research Issues. Sensors 2020, 20, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayes, A.; Rahayu, W.; Watters, P.; Alazab, M.; Dillon, T.; Chang, E. Achieving security scalability and flexibility using Fog-Based Context-Aware Access Control. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 107, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chickerur, A.; Joshi, P.; Aminian, P.; Semencato, G.T.; Pournasseh, L.; Nair, P.A. Classification and Management of Personally Identifiable Data. U.S. Patent Application No. 16/252320, 26 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).