Abstract

Risk assessment and emergency responses to ensure the safety of ships crossing the Arctic have gained tremendous attention in recent years. However, asymmetry in the probability that people will receive aid when navigating through the Arctic still exists because of the unsystematic allocation of rescue bases in the Arctic. At the same time, no study has proposed an overall solution to the problem of allocating rescue bases in the Arctic region to safeguard people’s interests. In this paper, we investigated the main natural factors affecting the safety of ship navigation in the Arctic based on the statistics of ship accidents in the Arctic from 1995 to 2004. The navigation risk of the Arctic was then assessed based on these natural factors, reflecting the need for rescue at all locations in the Arctic. Next, 37 cities with good infrastructure were selected among those along the Arctic as candidate locations for rescue bases. Finally, a new model was constructed based on the Set Covering Location Model, Double Covering Location Model, and P-Median Model to determine the optimal allocation of rescue bases in the Arctic. The rescue bases covered all the areas in the Arctic, and minimized cost in terms of distance and other economic factors. In addition, the constructed model ensured that two rescue bases were allocated to the areas with high navigation risk.

1. Introduction

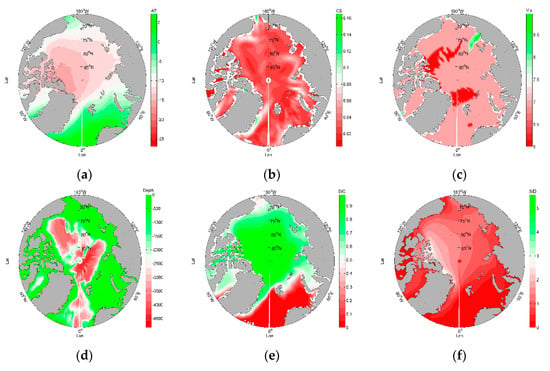

The sea ice in the Arctic has been melting at rapid rates due to the rising levels of global warming [1]. According to the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), it is highly likely that the Arctic sea ice will melt completely in late summer during the second half of the 21st century. Indeed, these conclusions were further confirmed by analyses of the Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) archives. This will lead to complete opening of the Arctic passages. However, the melting of sea ice is just one of the basic conditions that promote safe navigation in the Arctic. Given that the meteorological conditions of the Arctic are complex, there are many factors affecting the safety of ship navigation in the Arctic apart from sea ice. All these pose risks for objects navigating in the Arctic. Statistics indicate that more than 293 incidents occurred in the Arctic between 1995 and 2004 [2], which shows that emergency response and rescue strategies are required in the Arctic, given that people are navigating in the Arctic regions.

Recent years have witnessed an increase in the number of studies assessing the risks of Arctic navigation. Yet, few studies have focused on emergency response and rescue in the Arctic, especially the allocation of rescue bases in the Arctic. Presently, the number of rescue bases in the Arctic regions is not only small, but also each rescue base is built independently in the interests of the country building it, which not only leads to the waste of resources, but leaves many areas in the Arctic without a rescue bases, which in turn, causes asymmetry in the probability that people receive aid when navigating through the Arctic. To solve this problem, this study innovatively constructed a Set-Double Covering Median Model (SDCMM) to determine the best strategy for allocating rescue bases in the Arctic. We allocated rescue bases that not only covered all areas of the Arctic, but also minimized costs in terms of distance and other economic considerations. In addition, the constructed model ensured that the two rescue bases covered the areas with high navigation risks.

Many scholars have proposed models for allocating rescue bases; however many of them have focused on allocating rescue bases inland with fewer in coastal areas [3]. In 1826, Von Thünen [4] wrote the book titled, “The Isolated State”, which is regarded as the first study on the site-selection problem. The constructed model uses distance as a constraint to analyze the interaction between cities and land use, and explains the phenomenon of agricultural areas around cities. In 1909, Weber [5] addressed the industrial location problem. He investigated choosing the location of a warehouse so as to minimize the total distance between the warehouse and the customer. From then on, the problem of industrial layout was called the Weber problem. In 1964, Hakimi [6] wrote a paper on the P-Centre Model (PCM) for solving the challenge of minimizing the maximum distance between P facilities and all demand locations, which marked the beginning of modern theory on site selection. Drezner and Wesolowsky [7] proposed an algorithm to solve the PCM, which involved the numerical integration of ordinary differential equations and was computationally superior to methods using nonlinear programming. In 1965, Hakimi [8] proposed the P-Median Model (PMM) to minimize the product of the distance from P facilities to all demand points, and the demand of the demand points. Goldman [9] proposed an algorithm to solve the PMM with one server, which was based on a reduction procedure that may also yield useful simplification of problems involving general networks. Considering that solving the model with many servers needs too much computation, greedy algorithm is the most commonly used method to solve the model. Although the algorithm cannot guarantee that the obtained solution is the optimum solution, it can guarantee that the obtained solution is a satisfactory solution for policymakers [10].

Roth [11] and Toregas et al. [12] first proposed the Set Covering Location Model (SCLM) to choose the location of fire control centers and ambulances. This model mainly solves the problem of minimizing the number or cost of emergency service facilities when all demand points are covered. Roth [11] proposed one probabilistic approach to obtain optimal solutions for such large coverage problems, and his success supports the contention that this approach “may be of general applicability to various optimization problems”. The heart of the algorithm is obtaining independent locally optimum solutions. Toregas et al. [12] used linear programming supplemented by the addition of a single cut constraint to solve the SCLM. Aly and White [13] developed the SCLM where the shortest time between the emergency facility point and the demand points is a random variable. The model mainly describes how to determine the address of the service facility while minimizing the number of service facilities needed, when the time from the demand point to its nearest service facility is ≤ to a specified value.

Considering budget constraints and other aspects, scholars further proposed the Maximum Covering Location Model (MCLM), which is a transformation of the SCLM. Church and ReVelle [14,15] pioneered the MCLM and explored strategies to maximize the covered demand points when the number of facilities and coverage radius is known. The MCLM is regarded as one of the most effective models for solving the site-selection problem. However, the key assumption of the model is that the coverage is binary, that is, any demand point is either completely covered or not covered. This assumption may result in some demand points not being covered. In the actual allocation of rescue bases, a rescue base should provide service for each demand point whether the demand point is within the specific coverage radius of the rescue base or not, otherwise greater losses may be incurred in areas intended. To address this problem, Berman and Krass [16] proposed the Generalized Maximum Covering Location Model (GMCLM), in which each demand point was covered, but the coverage degree was defined to be between [0–1].

In 1997, Ogryczak [17] proposed the bi-objective model (BOM) for selecting an emergency facility location, which takes the average distance and the maximum distance to the emergency facility into consideration, striking a compromise between the two indicators. In 1998, Badri et et al. [18] established a multi-objective mathematical model (MOMM) to select the location of a fire station using a goal programming method. This model not only took the traditional time and distance into consideration, but also considered the cost of building the fire station. In 2011, Canbolat and von Massow [19] studied the problem of emergency facility layout when the location of the demand point is random. The goal was to minimize the expected maximum straight-line distance from the facility to the demand point. In 2017, Li et al. [20] proposed the Double Covering Location Model (DCLM) to identify the location of a rescue base. Their model was based on the characteristics of traffic flow and the statistics of maritime traffic accidents in the Bohai Sea and used genetic algorithms to obtain the optimal locations of the rescue bases. The model takes time, distance, double covering, and the number of bases into account, where double covering means that each rescue base covers two demand points at most. The objective of the model is to minimize the construction and operation costs of the marine emergency rescue system, on the premise that it can cover all the demand points.

Based on the above description, many models have been proposed for selecting the best locations for setting up rescue bases. The main models and their respective characteristics are shown in Table 1. To choose the best location for a rescue base in the Arctic, this study used the PMM, SCLM, and DCLM to comprehensively construct the Set-Double Covering Median Model (SDCMM). The constructed model enables the determination of the number and location of rescue bases in the Arctic, under the conditions that all demand points are within the range of rescue base and the total distance of the rescue bases to all demand points and the total construction cost of all rescue bases are minimized. At the same time, the model can guarantee that two rescue bases cover the sea areas with high navigation risk.

Table 1.

The main models for the optimal layout of rescue bases and their characteristics.

Overall, the objectives of this study were to (1) construct a new model to select the location of a rescue base, and (2) provide the optimal layout of rescue bases in the Arctic. The study is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the technical process and modeling idea of this study. Section 3 describes the methods and results of the risk assessment for navigation in the Arctic. Section 4 presents the candidate rescue bases and estimation of their construction costs. The results are provided in Section 5 and the final section (Section 6) provides the conclusions and discussion.

2. Methods

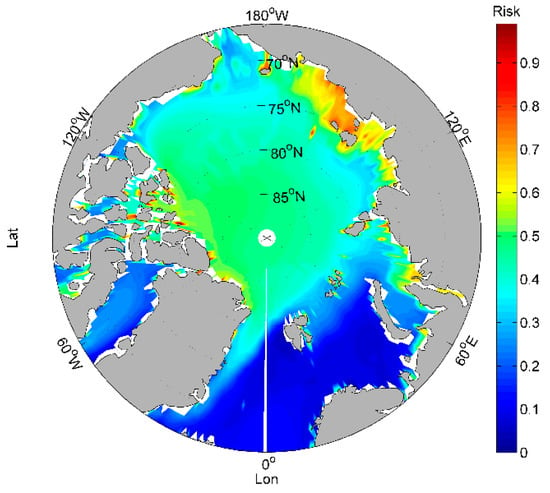

2.1. Technical Process

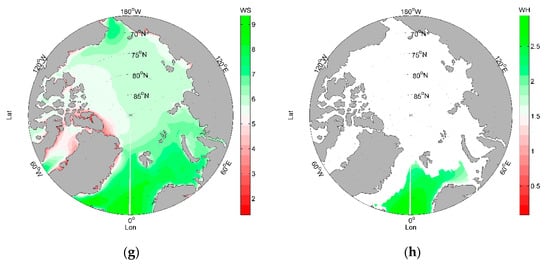

To explore the main factors affecting navigation risk in the Arctic, this paper firstly describes the types and frequency of ship accidents in the Arctic, based on the limited statistical data available. Secondly, based on the main natural factors affecting navigation risk in the Arctic and the monthly average data of these factors in the past 17 years (2000–2016) in the Arctic, the navigation risk is calculated and the final risk values of each sea area are normalized. Next, the number and location of candidate rescue bases along the Arctic coast are determined, and the costs of building each of the bases into integrated rescue bases comprising airports, ports, and general hospitals are assessed on the basis of existing facilities. To reduce the cost of building a rescue base, the rescue bases selected in this paper currently have the necessary infrastructure such as airports, ports, and hospitals. Finally, based on the principles of PMM, SCLM, and DCLM, the number and location of rescue bases along the Arctic coast are determined. The selected bases are arrived at after considering the distance, construction costs, and the needs of each demand point, and they cover all areas in the Arctic. The flow chart of the technical process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the technical process.

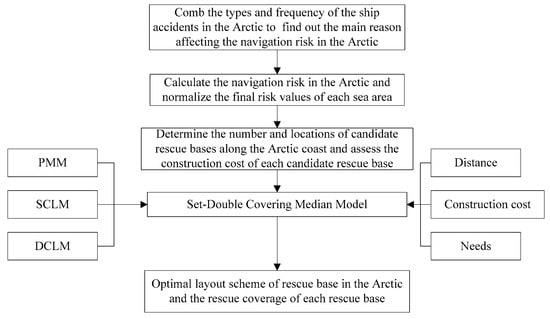

2.2. Set-Double Covering Median Model

The model established in this study is a combination of the PMM, SCLM, and DCLM, and is therefore named SDCMM. The core of the constructed model is the PMM. The following three conditions are required before running the PMM: the number and locations of demand points, the number and locations of candidate rescue bases, and the number of rescue bases to be built which is P [8]. Since this paper requires two rescue bases to be responsible for areas with high navigation risk, it is necessary to determine the locations that the two rescue bases are responsible for by calculating navigation risk values of each sea area in the Arctic when calculating the cost of each scheme using the evaluation function. The evaluation function of SDCMM is defined as:

where is the number of demand points with low risk that only one rescue base is responsible for, is the number of demand points with high risk that two rescue bases are responsible for, is the number of candidate bases, is the distance between the th demand point and the th rescue base, is the construction cost of the th rescue base, and are used to determine whether the th rescue base is responsible for the th demand point, and is used to determine whether to select the th candidate base as the final rescue base.

The constraints are defined as:

Formula (4) indicates the number of rescue bases allocated to a demand point with low risk that only needs one rescue base. Formula (5) indicates the number of rescue bases responsible for a demand point with high risk that needs two rescue bases. Formula (8) indicates that the number of the final selected rescue bases should be P. Formulas (6) and (7) indicate that if a candidate rescue base is not selected to be the final rescue base, the candidate rescue base will not be able to provide rescue services for the demand points. That is, if , then .

The model constructed above guarantees that, under the premise of planning to build P rescue bases, the selected rescue bases require minimal total costs including distance and economy, and the selected rescue bases can cover the whole Arctic sea area. To calculate the total cost of constructing base P while considering the distance and economic changes, we calculate the total cost under different P conditions and choose the best P with the lowest total cost as the final number of rescue bases to be constructed.

Since the dimensions of distance and construction costs are different, it is necessary to make them dimensionless. This is achieved using the method is shown in Formula (9). The final cost is calculated under the assumption that distance and economic cost have the same weight. Different weights for distance and economic cost are also considered to determine the priority objects when selecting the location of the rescue base, which depends on the wishes of decision-makers.

where is the dimensionless data, is the raw data, is the minimum value of the data set and is the maximum value of the data set.

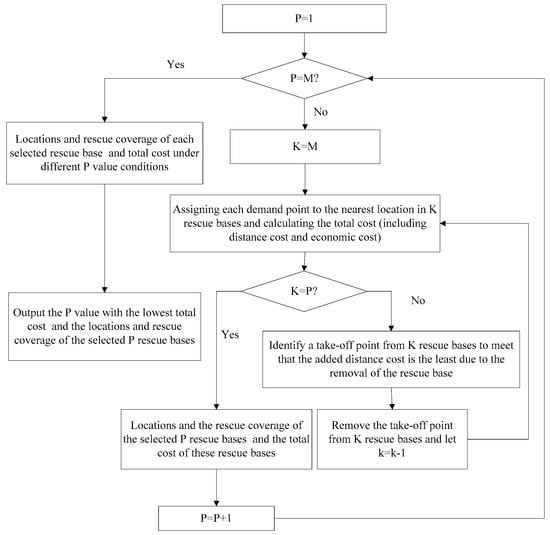

A greedy algorithm is useful to solve the model and the flow chart of the algorithm is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of greedy algorithm to solve Set-Double Covering Median Model (SDCMM).

4. Candidate Rescue Bases and Estimation of Their Construction Costs

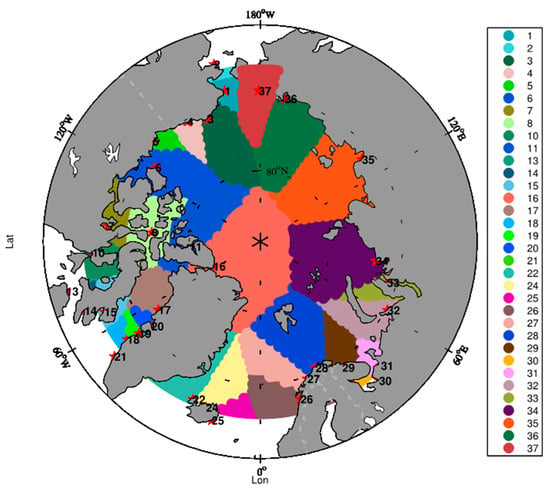

4.1. Candidate Rescue Bases in the Arctic

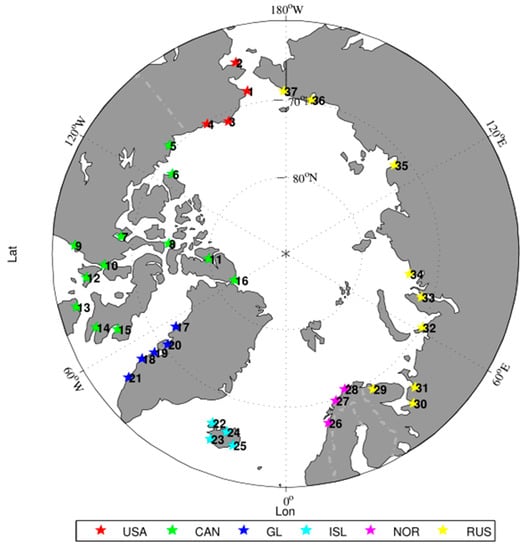

The candidate rescue bases selected in this study were required to meet two conditions: (1) the locations of the candidate rescue bases should be north of 60° N and along the Arctic Ocean; (2) the candidate rescue bases should be cities or towns with airports, ports, and hospitals. If there were no cities or towns meeting the facility conditions in a large area, priority was given to the cities and towns with airports. A total of 37 cities and towns were selected to be the candidate rescue bases in the Arctic and the details of these candidate rescue bases are shown in Table 7. Figure 5 shows the distribution of these candidate locations. All the data shown in Table 7 were obtained from Wikipedia.

Table 7.

The details of the candidate rescue bases in the Arctic.

Figure 5.

The distribution of these candidate locations.

4.2. Estimation of the Construction Cost of Each Candidate Rescue Base

Given the complexity of estimating the construction cost of each candidate rescue base, we utilized the level evaluation approach to evaluate the construction cost of each rescue base. The steps used were as follows:

Step 1: Assessment of airport facilities, port facilities, and medical conditions of each candidate rescue base was performed. For example, if the candidate rescue base did not have airport facilities, the level of the airport facilities for such a base was 1; if the base had airport facilities but the conditions of the airport facilities were not good, the level of the airport facilities for such a base was 2; if the base had good airport facilities, then the level of the airport facilities for such a base was 3. A similar approach was used for the conditions of port facilities and hospitals in each candidate rescue base. The level was determined on the basis of the description of each candidate rescue base in Wikipedia.

Step 2: Assessment of the construction cost of each candidate rescue base. For example, if the level of airport facilities of the base was 1, then the construction cost of such facilities was 2. If the level of the airport facilities of the base was 2, then the construction cost of such facilities was 1. If the level of the airport facilities of the base was 3, then the construction cost of such facilities was 0. Similar assessments were performed for the construction cost of port facilities and hospitals in each candidate rescue base. The total construction cost of each candidate rescue base was the sum of its airport, port, and hospital construction costs.

Since the construction cost of each candidate base was also normalized in this study, the final result of the construction cost of each rescue base is reasonable. Table 8 shows the level of infrastructure and the total construction cost for each candidate base.

Table 8.

The level of infrastructure and the total construction cost for each candidate base.

5. Results

5.1. Performance of Greedy Algorithm

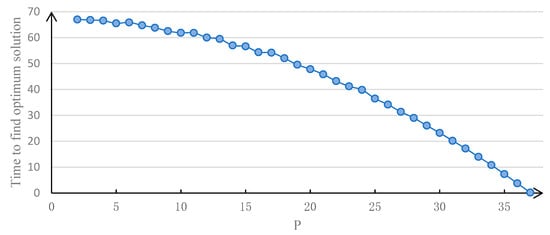

Since the greedy algorithm is a local search algorithm and the result of each iteration is to find the local optimal solution, the final result of the greedy algorithm is likely to be the local optimal solution. At the same time, when using the greedy algorithm to solve the model constructed here, this paper assumed that all candidate bases were selected as the final result first, and then removed the candidate bases one by one, which minimized the added cost in each iteration until the number of remaining bases equaled the number of bases that needed be built (Figure 2). Therefore, the convergence speed of the greedy algorithm to solve the model depended on the number of bases that needed be built, which was the value of P. The time needed to obtain the optimal solution using the greedy algorithm with different P is shown in Figure 6. This shows that the calculation speed of the greedy algorithm is very fast, although it cannot guarantee that the obtained solution is the best solution. Note that the central processing unit of the computer used was i3-3227U (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and the random access memory capacity of the computer was 4G. The calculation is based on MATLAB 2104a software (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Figure 6.

The time needed to obtain the optimal solution using greedy algorithm with different P.

5.2. Results of SDCMM

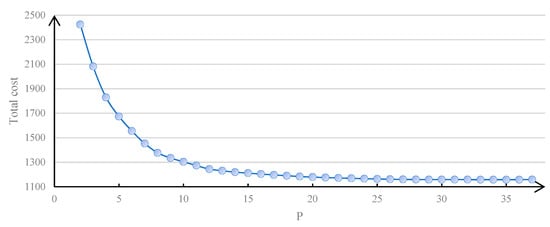

Figure 7 shows the total construction cost under different P. It can be seen that the least total construction cost appears when . At the same time, when P is less than 35, the total cost decreases with P. However, when P is more than 35, the total cost increases with P. The result is related to the value of the construction cost of each candidate rescue base and the weight of the distance cost and construction cost.

Figure 7.

The total construction cost under different P.

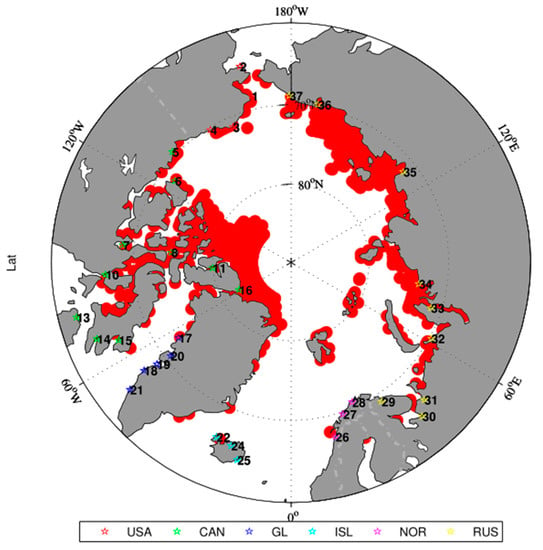

Note that when P = 35, the selected rescue base “Reykjavik” is responsible for no need points, which is due to the construction cost for “Reykjavik” being 0. Since the approach used to calculate construction cost of each candidate rescue base in this paper is the simplified level evaluation method—which is not entirely reasonable because the construction cost of each candidate rescue base cannot be 0—the final number of selected rescue bases in this paper is 34, which does not include “Reykjavik”. The locations of the selected rescue bases and their rescue coverage are shown in Figure 8. The serial number of each rescue base is shown in Table 8.

Figure 8.

The locations of the selected rescue bases and their rescue coverage.

The need points that require two rescue bases to be responsible for them are shown in Figure 9 and details can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 9.

The need points that require two rescue bases to be responsible for them.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

As the Arctic passages gradually open, it is important to study the locations of Arctic rescue bases for countries around the Arctic region. In this study, a total of 37 candidate rescue bases were determined by consulting a large number of data sets. The SDCMM was innovatively constructed based on PMM, SCLM, and DCLM to determine the final locations of the rescue bases in the Arctic. The constructed model not only ensures that the selected rescue bases can cover all areas in the Arctic region, it also minimizes the total distance cost and the total construction cost of the rescue base from each demand point. In addition, two rescue bases are allocated to cover each demand point with a high navigation risk.

Although this study provides innovative methods to address the problem of allocating rescue bases in the Arctic, the following issues still exist:

- (1)

- This study only considers the natural factors when assessing the navigation risk in the Arctic; however, this is incomplete as other non-natural factors may also affect the navigation risk. Moreover, the data used to calculate the risk value were the average of 17 years from 2001 to 2016, which may lead to neutralization for some areas with high risk. Therefore, it is important to assess the navigation risk by calculating the frequency of various extreme weather occurrences in each sea area to solve this problem. Additionally, statistical data on ship accidents should be integrated into the calculated risk data for each sea area. In this case, the risk value of the sea area where the accident occurred is expected to be high.

- (2)

- The method used to estimate the construction cost of each candidate base in this study was relatively simple. Although the method reflects the current situation of each rescue base, the difference in construction costs determined by this method is not significant. Hence, the estimated construction cost does not express the current situation of each candidate base sufficiently. Next, the construction standard and calculation of the construction cost of each rescue base should be discussed with relevant professionals in detail.

- (3)

- The weights of economic cost and distance cost in the evaluation function of this study are the same. The next step is to explore the optimal layout of the rescue base under different weights for the two costs. The weights of the two costs will depend on the intention of the decision-maker.

- (4)

- The algorithm to solve SDCMM is based on the idea of a greedy algorithm, which cannot guarantee that the obtained solution is the optimum solution. At the same time, although many new algorithms, such as genetic algorithms [20], can be used to solve conditioning optimization problems, it is also hard for them to obtain the optimum solution in a reasonable time in large-scale instances, and these algorithms also do not guarantee the accuracy of the solution theoretically [25]. With the development of artificial intelligence in recent years, deep learning has been used to solve many problems, such as conditioning optimization problems. Shoma et al. [25] applied deep learning and reinforcement learning to the “Traveling Salesman Problem” and obtained good results. Therefore, the next step is to apply deep learning and reinforcement learning to find the best solution with different P of the model constructed in this paper.

Overall, in this study, we innovatively constructed a SDCMM based on PMM, SCLM, and DCLM to determine the final locations of rescue bases in the Arctic. The study is of great significance in the context of global warming. Although there are some shortcomings in this study, we have discussed how to solve these limitations in the future. The authors plan to solve the shortcomings of this study and improve the allocation of rescue bases in the Arctic.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-8994/11/9/1073/s1, Table S1: the details of the need points that need 2 rescue bases be responsible for.

Author Contributions

Y.S. is the first author of this paper and the experiments and writing are mainly done by him. R.Z. is the corresponding author of the paper and he provided the ideas for writing the paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding and the APC was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (serial number item: 4197060570).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AT | air temperature |

| ANN | artificial neural network |

| AR5 | Fifth Assessment Report |

| BOM | bi-objective model |

| CS | current speed |

| C3S | Copernicus Climate Change Service |

| CMIP | Climate Model Intercomparison Project |

| Depth | water depth |

| DCLM | Double Covering Location Model |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| GMCLM | Generalized Maximum Covering Location Model |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ICOADS | International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set |

| MCLM | Maximum Covering Location Model |

| MOMM | Multi-Objective Mathematical Model |

| MIU | Marine Intelligence Unit |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| NCDC | National Climate Information Centre of the United States |

| NSF | National Science Foundation |

| ORA | Ocean Reanalysis Program |

| PMM | P-Median Model |

| PCM | P-Centre Model |

| SDCMM | Set-Double Covering Median Model |

| SCLM | Set Covering Location Model |

| SIT | sea ice thickness |

| SID | sea ice density |

| SODA | Simple Ocean Data Assimilation |

| Vis | atmospheric visibility |

| WS | wind speed |

| WH | wave height |

References

- Stroeve, J.; Holland, M.M.; Meier, W.; Scambos, T.; Serreze, M. Arctic sea ice decline: Faster than forecast. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arctic Council. Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment Report 2009; Arctic Council: Tromsø, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, L.; XU, J. Multi-objective optimization of oil spill assistant site selection in the Bohai sea. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2016, 37, 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. The Research of Maritime Accidents Based on the Support Vector Machines; Wuhan University of Technology: Wuhan, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, A. Theory of Industrial Location; San José State University Department of Economics: San Jose, CA, USA, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi, S.L. Optimum locations of switching centers and the absolute centers and medians of a graph. Oper. Res. 1964, 12, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, Z.; Wesolowsky, G.O. A new method for the multifacility minimax location problem. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1978, 29, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakimi, S.L. Optimum Distribution of Switching Centers in a Communication Network and Some Related Graph Theoretic Problems. Oper. Res. 1965, 13, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.J. Optimal Center Location in Simple Networks. Transp. Sci. 1971, 5, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi-xi, G.H.; Jiang-yan, O.U. The Study of Greedy Dropping Heuristic Algorithm in Discrete Network Location. Chin. J. Syst. Sci. 2010, 18, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, R. Computer Solutions to Minimum-Cover Problems. Oper. Res. 1969, 17, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toregas, C.; Swain, R.; Revelle, C.; Bergman, L. The Location of Emergency Service Facilities. Oper. Res. 1971, 19, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.A.; White, J.A. Probabilistic Formulation of the Emergency Service Location Problem. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1978, 29, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, R.; Revelle, C. The maximal covering location problem. Pap. Reg. Sci. 1974, 32, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, R.L.; ReVelle, C.S. Theoretical and computational links between the p-median, location set-covering, and the maximal covering location problem. Geogr. Anal. 1976, 8, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, O.; Krass, D. The generalized maximal covering location problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2002, 29, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogryczak, W. On cent-dians of general networks. Locat. Sci. 1997, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M.A.; Mortagy, A.K.; Alsayed, C.A. A multi-objective model for locating fire stations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 110, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbolat, M.S.; Von Massow, M. Locating emergency facilities with random demand for risk minimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 10099–10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W. Optimization Method of Emergency rescue Base Site Selection in Bohai Sea. In Journal of Henan University of Science and Technology (Natural Science); Luoyang Post Office: Henan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, L. Generation and Analysis of Gridded Visibility Data in the Arctic. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultepe, I.; Sharman, R.; Williams, P.D.; Zhou, B.; Ellrod, G.; Minnis, P.; Trier, S.; Griffin, S.; Yum, S.S.; Gharabaghi, B.; et al. A Review of High Impact Weather for Aviation Meteorology. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2019, 176, 1869–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hong, M.; Wang, B. Disaster assessment and risk zoning concerning the South China Sea and Indian Ocean safety. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2012, 31, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Ge, S.; Zhang, R. Marine Environmental Risk Assessment and Regionalization of the Northwest Passage in the Arctic; Annual report on investment security of china’s “the belt and road” construction (2017–2018); Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miki, S.; Yamamoto, D.; Ebara, H. Applying Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning to Traveling Salesman Problem. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computing, Electronics & Communications Engineering (iCCECE), University of Essex, Southend, UK, 16–17 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).