Abstract

The nonadiabatic Heisenberg model presents a nonadiabatic mechanism generating Cooper pairs in narrow, roughly half-filled “superconducting bands” of special symmetry. Here, I show that this mechanism may be understood as the outcome of a special spin structure in the reciprocal space, hereinafter referred to as “k-space magnetism”. The presented picture permits a vivid depiction of this new mechanism highlighting the height similarity as well as the essential difference between the new nonadiabatic and the familiar Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer mechanism.

1. Introduction

The nonadiabatic Heisenberg model (NHM) [1] is an extension of the Heisenberg model [2] going beyond the adiabatic approximation. It is based on three postulates related to the atomic-like motion [2,3,4] of the electrons in narrow, roughly half-filled energy bands. An atomic-like motion is characterized by electrons occupying localized states which for their part move as Bloch waves through the crystal. The NHM does not represents the localized states by (hybrid) atomic functions but solely by symmetry-adapted and optimally-localized Wannier functions forming an exact unitary transformation of the Bloch functions of a narrow, roughly half-filled energy band.

The energy bands in the band structures of the metals are degenerate at several points and lines (of symmetry) of the Brillouin zone. Hence, it is generally not possible to find narrow, roughly half-filled closed energy bands in the band structures of the metals as they are required for the construction of optimally localized Wannier functions. However, in the band structures of those metals that experimentally prove to be superconductors, the construction of such Wannier functions becomes possible if we allow the Wannier functions to be spin dependent [5]. This observation leads to the definition of “superconducting bands” [5]: The Bloch functions of a superconducting band can be unitarily transformed into optimally localized spin-dependent Wannier functions that are symmetry-adapted to the full space group of the metal.

Within the NHM, the atomic-like motion in a superconducting band produces Cooper pairs below a transition temperature [6]. The aim of the paper is to show that this nonadiabatic mechanism can be understood as the outcome of a special spin structure in the reciprocal space referred to as “-space magnetism”. In Section 2, we declare what we mean by -space magnetism. In Section 3, we show that -space magnetism leads directly to the formation of Cooper pairs at low temperatures. In Section 4, we finally show that the NHM provides an interaction producing -space magnetism in narrow, roughly half-filled superconducting bands when we leave the adiabatic approximation.

2. k-Space Magnetism

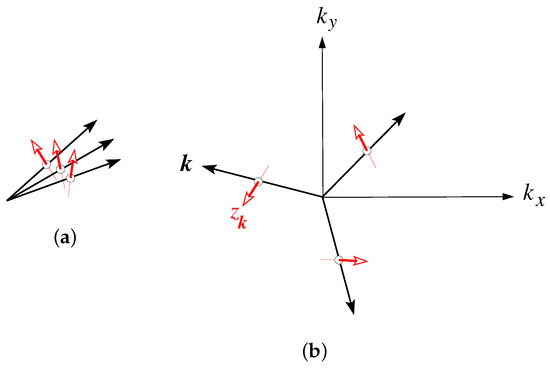

Within the NHM, strongly correlated electrons in a narrow, roughly half-filled superconducting band produce a special spin structure at the Fermi level that we call “-space magnetism”: the electron spins of the Bloch electrons are no longer parallel or anti-parallel to a fixed symmetry axis (usually the z axis), but are parallel or anti-parallel to an axis determined by the vector of the electron, as is visualized in Figure 1. The direction of changes continuously in the space and is not independent of in a narrow, roughly half-filled superconducting band. The spin of the Bloch electron at wave vector still may lie parallel (for ) or anti-parallel (for ) to the predefined axis. Thus, -space magnetism does not create a magnetic field and is invariant under time inversion.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the space magnetism in a narrow, roughly half-filled superconducting band: the black arrows show the vectors of Bloch electrons moving in general positions at the Fermi level, and the red arrows indicate the symmetry axis of the spin of the Bloch electron with wave vector . The axes generally intersect the drawing plane. Panel (a) demonstrates that the axes change continuously in space; and Panel (b) shows the vectors of three Bloch electrons connected by symmetry (in a crystal with the hexagonal space group P3) and demonstrates that also the axes are connected by symmetry.

3. k-Space Magnetism Producing Cooper Pairs

Consider an electron system exhibiting -space magnetism at the Fermi level. The interaction producing the -space magnetism is defined in Section 4; here, we assume it to exist.

At any scattering process in the electron system , the total electron spin of the scattered electrons is not conserved since the spin direction is dependent. Hence, the electrons must interchange spin angular momenta with the lattice of the atomic cores. Consequently (Section 3.1 of Ref. [6]), at any electronic scattering process, two crystal-spin-1 bosons are excited or absorbed.

At zero (or very low) temperature, the crystal-spin-1 bosons will be only virtually excited. That means that each boson pair is reabsorbed instantaneously after its generation. Hence, whenever a boson pair is excited during a certain scattering process

of the two electrons and , this boson pair is reabsorbed instantaneously during a second scattering process

of two other electrons and . Consequently, the resulting total scattering process

must conserve the total electron spin. Only in this case, the boson pair created during the first process in Equation (1) is completely reabsorbed during the second process in Equation (2). However, also at the scattering processes in Equation (3) of four electrons, the total spin is generally not conserved since the spin direction still is dependent.

The only scattering processes within conserving the total electron spin are scattering processes between Cooper pairs: since the system is invariant under time-inversion, the spins of the Bloch states labeled by and by lie exactly opposite. When both states are occupied at the same time, they form a Cooper pair with exactly zero total spin. Hence, any scattering process between Cooper pairs

conserves the total spin angular momentum within , see the detailed group-theoretical discussion in Section 3.2 of Ref. [6]. This scattering process (Equation (4)) comprises the two processes

destroying a Cooper pair and creating a boson pair, and the subsequent process

recomposing the Cooper pair and reabsorbing the boson pair. This only possible combined scattering process within represents the well-known Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) mechanism [7] in , see Section 3.2 of Ref. [6]. However, the mechanism in differs from the BCS mechanism because it is effective solely between Cooper pairs. It necessarily produces Cooper pairs possessing only one half of the degrees of freedom of free electrons. This necessary reduction of the degrees of freedom may be compared with the effect of constraining forces in classical systems. Thus, we speak of quantum mechanical constraining forces stabilizing the Cooper pairs in [6], or, more illustratively, by “spring mounted Cooper pairs” [8].

5. Discussion

The aim of this paper is to give a graphic description of the nonadiabatic mechanism of Cooper pair formation defined within the NHM. The presented picture clearly shows the peculiar features of the Cooper pair formation within a superconducting band: first, the postulates of the NHM suggest that the strongly correlated atomic-like motion in a narrow, roughly half-filled superconducting band produces -space magnetism in the nonadiabatic system (as described in Section 2), and, secondly, at sufficiently low temperatures the -space magnetism produces Cooper pairs in turn. This picture clearly demonstrates that the formation of Cooper pairs produced by -space magnetism shows a great resemblance, but also a striking difference as compared with the familiar BCS mechanism [7]. On the one hand, the formation of Cooper pairs is still mediated by bosons but, on the other hand, the electrons necessarily form Cooper pairs below a transition temperature. This necessity of the Cooper pair formation we compare with the effect of constraining forces in classical systems and, consequently, we speak of constraining forces stabilizing the Cooper pairs [6]. There is evidence that these constraining forces are essential for the formation of Cooper pairs, see, e.g., the Introduction of Ref. [9]. In this context, the question of whether there exists an attractive interaction between the electrons is of secondary importance.

Funding

This publication was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Stuttgart.

Acknowledgments

I am very indebted to Guido Schmitz for his support of my work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NHM | Nonadiabatic Heisenberg model |

| BCS mechanism | Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer mechanism |

References

- Krüger, E. Nonadiabatic extension of the Heisenberg model. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. Zur Theorie des Ferromagnetismus. Z. Phys. 1928, 49, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, N.F. On the transition to metallic conduction in semiconductors. Can. J. Phys. 1956, 34, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, J. Elelectron correlations in narrow energy bands. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1963, 276, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, E.; Strunk, H.P. Group Theory of Wannier Functions Providing the Basis for a Deeper Understanding of Magnetism and Superconductivity. Symmetry 2015, 7, 561–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, E. Modified BCS Mechanism of Cooper Pair Formation in Narrow Energy Bands of Special Symmetry I. Band Structure of Niobium. J. Supercond. 2001, 14, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, E. Modified BCS Mechanism of Cooper Pair Formation in Narrow Energy Bands of Special Symmetry III. Physical Interpretation. J. Supercond. 2002, 15, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, E. Constraining Forces Stabilizing Superconductivity in Bismuth. Symmetry 2018, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).