Population Mobility in the Wake of COVID-19 in the US Northeast Region: Lessons for Regional Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

Understanding Migration During the COVID-19 Era: What We Know and What We Do Not Know

- R.Q.-1: What were the trends of COVID-era population movement in the NE region?

- R.Q.-2: What were the infrastructure-related and socioeconomic outcomes of COVID-era movements for receiving communities, based on housing experts’ perspectives in high-inflow areas of the region?

- R.Q.-3: What lessons can be drawn for regional planning efforts aiming to achieve sustainable and just outcomes of disaster-induced population mobilities?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modeling

2.2. Focus Groups

3. Results

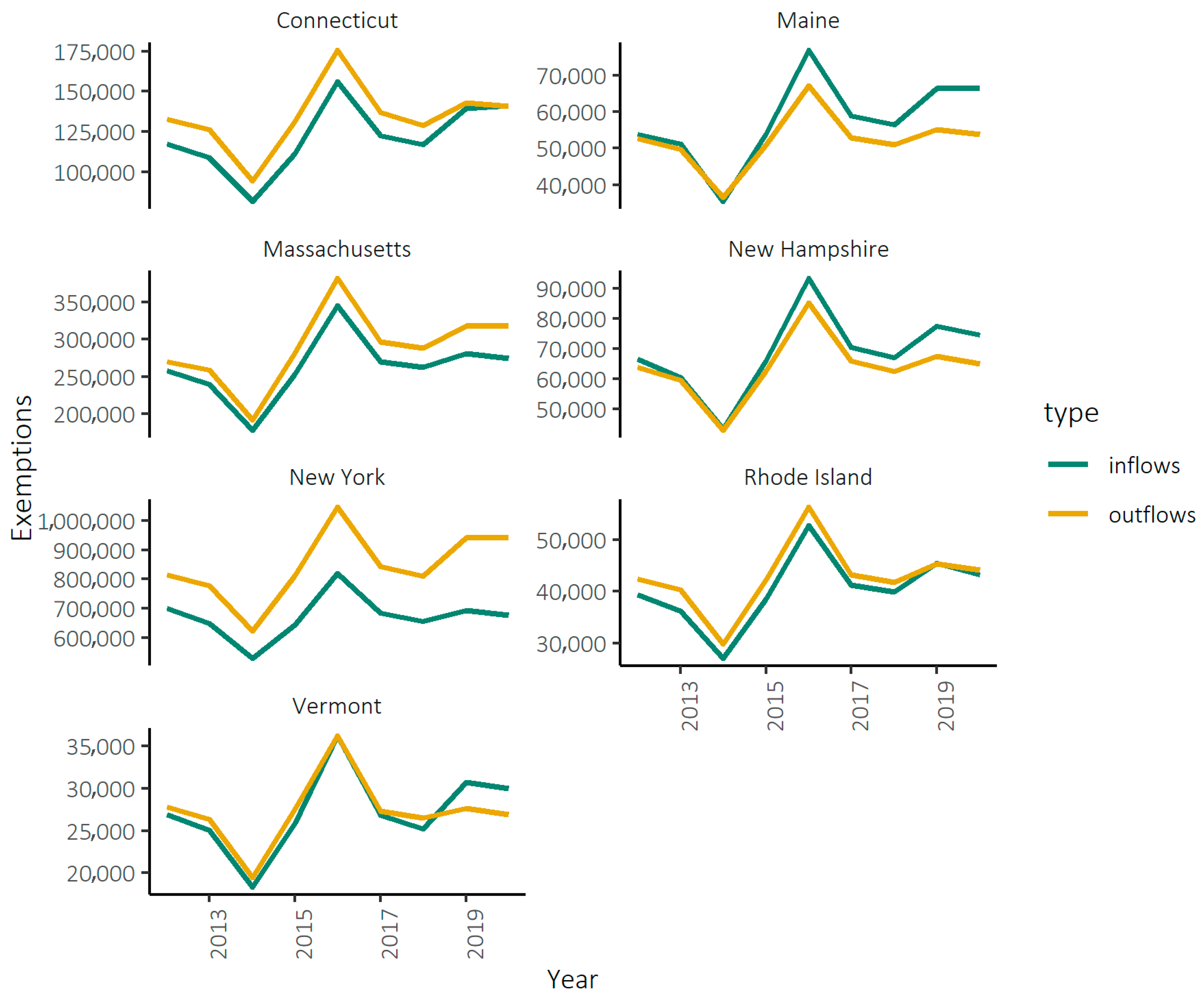

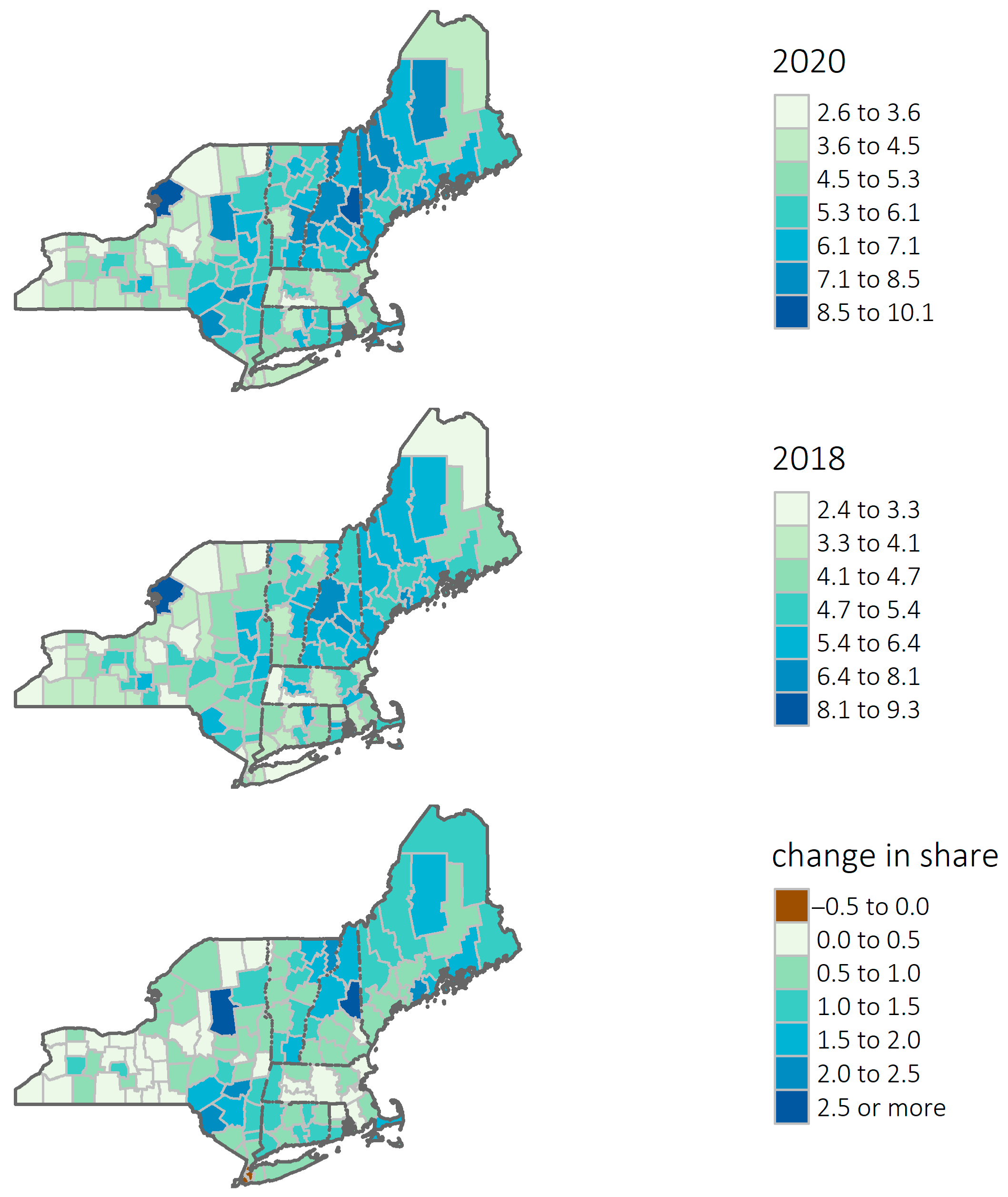

3.1. RQ1 Modeling: Northeast US Migration Trends During COVID-19

3.2. RQ2: Outcomes for Receiving Communities

3.2.1. Housing-Related Challenges

We’ve seen building lots that no one would have put on the market. Or they held on the market for years... because it’s next to a train track or because [it’s on] high water table. You have to put a raised septic system and that…costs you [...] 35-40 grand on top of everything on a hill. You know, that’s just really not desirable, cramped up. And they sell!!!

Last summer, I sold a property for this older woman. Her husband had passed away. Owning a house was just too much for her. I had been speaking to her for three years, she was ready to get out. And she just wanted a place to rent because she didn’t want to be a homeowner anymore. And [for] three years [...] I’m posting stuff on Front Porch forum [...], Putting stuff on Facebook saying “Does anybody know of a rental?” And nobody!!!

We have no labor! [...] You have people moving here because they want to be in the country. But there’s no one here to service them. Because there’s no lodging for service people. We have no tradespeople. The average age of tradespeople is 59 years old. There’s no young people to take over those positions. And I’d gladly welcome migrants to come here, with job skills, because there’s [an] endless amount of work, but there’s no place for them to live [...].

3.2.2. Infrastructure-Related Challenges

3.2.3. Socioeconomic Challenges: Growing Pressure on Low-Income Populations and Businesses

[We] had a problem with finding teachers, bus drivers, electricians… People to work at banks, people to work at the hotels, people to work at the ski mountain. It’s impossible to find, or very hard to find people to work… I think it’s similar to what our discussion was on the “to build affordable housing doesn’t make sense anymore.” It’s the same… We all want to have [small businesses] in our main street in the small towns. But if you can’t afford someone to come here to work there, it’s [a] challenge right now!

All the [flood-impacted] housing that was owner-occupied [after] the last two floods is no longer owner-occupied. Somebody has bought it. Somebody has smacked it back together. And now it’s rented out to the people that have the least options.

3.3. RQ3: Lessons for Strategic Regional Planning

I’d say there’s a lot of policy, sort of, incentives that need to go. [...] We’ve touched on [...] points, or the financial feasibility piece with developers. [...] Whether that looks like grants or lower interest loans, or some of the other financial tools, that states can use to incentivize the specific types of development they need.

[Planning should focus on] making sure that you [the towns] are building in places that are not in floodplains [...] at least to the best you can. So, the resiliency planning, that’s a [...] buzz topic for a lot of communities right now. It’s figuring out, “okay, well, what makes the most sense for our long-term plan? Where do we want to see growth? And then how do we incentivize the growth we want to see in the areas we want to see it?” And just to make sure that’s all worked in there, the population pieces, the environmental pieces, demographic pieces, transportation... All of it.

Government moves slow. Sometimes at a snail’s pace, especially when you’ve got a gazillion people that need to check the box before you can do anything. [...] You need to have a plan, and then you have to find the money, and then you have to get city council approval, and it’s just a lot of steps to make anything happen.

We have declining school enrollment, and so the schools are closing, you know. We do need more people to pay into the system, but we also need to make those investments in housing and infrastructure. So that there’s this place for them to come. And you know, in Vermont, there, there are still contingents who think like, we’re actually out of space, or we’ll lose our rural character if we build any more. But Vermont could double its population density and still be less dense than Tennessee.

The community engagement piece is incredibly important. [...] People don’t like change, period. So, [...] if you can hear them talk about what they want to see and help visualize what sort of policy decisions can help them get there, you know, you can have some success. Because I think if you ask a lot of people, they will bring up the same topics. They’ll bring up the fact that they’re concerned about their community... That they won’t be able to live there; that their kids won’t be able to live there; that, you know, their coffee shop is shutting down as well. But then a specific development might come forward. And [they are] like, “well, that’s not the right place for that. [It] is really important, making sure people understand, sort of, what the benefit is. Because their biggest asset, if they’re a homeowner, is their home, and they’re nervous about anything that would potentially harm that.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Argent, N.; Plummer, P. Counterurbanisation in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic in New South Wales, 2016–21. Habitat Int. 2024, 150, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzow, A. Exodus from Urban Counties Hit a Record in 2021; Economic Innovation Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haslag, P.H.; Weagley, D. From LA to Boise: How Migration Has Changed During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2022, 59, 2068–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Su, Y. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Demand for Density: Evidence from the U.S. Housing Market. Econ. Lett. 2021, 207, 110010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, A.; Bloom, N. The Donut Effect of COVID-19 on Cities (No. 28876); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28876 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Teicher, H.M.; Phillips, C.A.; Todd, D. Climate Solutions to Meet the Suburban Surge: Leveraging COVID-19 Recovery to Enhance Suburban Climate Governance. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, M. Record Wave of Americans Fled Big Cities for Small Ones in 2023. Bloomberg, CityLab. 7 May 2024. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-07/record-wave-of-americans-fled-big-cities-for-small-ones-in-2023 (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Schultz, J.; Elliott, J.R. Natural Disasters and Local Demographic Change in the United States. Popul. Environ. 2013, 34, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Wisconsin-Madison. Many Rural Americans Are Still “Left Behind”. University of Wisconsin–Madison, Institute of Research on Poverty. Available online: https://www.irp.wisc.edu/resource/many-rural-americans-are-still-left-behind/#_edn3 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Leichenko, R.M.; Solecki, W.D. Climate Change in Suburbs: An Exploration of Key Impacts and Vulnerabilities. Urban Clim. 2013, 6, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C. Who Are America’s “Climate Migrants,” and Where Will They Go? Urban Institute. Available online: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/who-are-americas-climate-migrants-and-where-will-they-go (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Hauer, M.E.; Evans, J.M.; Mishra, D.R. Millions Projected to Be at Risk from Sea-Level Rise in the Continental United States. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Nkonya, E.; Galford, G.L. Flocking to Fire: How Climate and Natural Hazards Shape Human Migration Across the United States. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2022, 4, 886545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K. People and Coastal Ecosystems Adapt to Relative Sea-Level Rise. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1510–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Dilkina, B.; Moreno-Cruz, J. Modeling Migration Patterns in the USA Under Sea Level Rise. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Lustgarten, A.; Goldsmith, J.W. New Climate Maps Show a Transformed United States; ProPublica: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lustgarten, A. How Climate Migration Will Reshape America. NY Times Magazine. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/09/15/magazine/climate-crisis-migration-america.html (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Coin, G. Upstate NY Cities Named Among Best ‘Climate Havens’ as the World Grows Hotter. Syracuse. Available online: https://www.syracuse.com/weather/2021/02/upstate-ny-cities-among-best-climate-havens-as-the-world-grow-hotter.html (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Jacobson, L. Americans are Fleeing Climate Change—Here’s Where They Can Go. CNBC. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/04/21/climate-change-encourages-homeowners-to-reconsider-legacy-cities.html (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Yoder, K. Fleeing Global Warming? ‘Climate Havens’ Aren’t Ready Yet. WIRED. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/fleeing-global-warming-climate-havens-arent-ready-yet/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Massey, D.S.; Arango, J.; Hugo, G.; Kouaouci, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Taylor, J.E. Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1993, 19, 431–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, H.; Castles, S.; Miller, M. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 6th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnifield, M.P. The Dust Bowl: Men, Dirt, and Depression; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C.J.L.; Piracha, A. Strategic Planning for Urban Sustainability. Land 2025, 14, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L.; Balducci, A.; Hillier, J. Situated Practices of Strategic Planning: An International Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Savini, F. Strategic Planning for Degrowth: What, Who, How. Plan. Theory 2025, 24, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infield, E.; Kuru, O.D.; Cotter, A.; Renski, H.C. Insights for Receiving Communities in Planning for Equitable and Positive Outcomes Under Climate Migration; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper; WP24EI1; Lincoln Institute for Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kuru, O.D.; Ganapati, N.E.; Marr, M. Perceptions of Local Leaders Regarding Post-Disaster Relocation of Residents in the Face of Rising Seas. Hous. Policy Debate 2022, 33, 1124–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid Uddin, K.A.; Piracha, A. Unequal COVID-19 Socioeconomic Impacts and the Path to a Sustainable City and Resilient Community: A Qualitative Study in Sydney, Australia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2474184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, H.; Maire, Q.; Cook, J.; Wyn, J. Liminality, COVID-19 and the Long Crisis of Young Adults’ Employment. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2023, 58, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, M.; Bandhold, H. Scenario Planning: The Link Between Future and Strategy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Krys, C. Scenario-Based Strategic Planning: Developing Strategies in an Uncertain World; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bijak, J. From Uncertainty to Policy: A Guide to Migration Scenarios; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zehner, E. How to Embrace and Navigate Uncertainty; Lincoln Institute for Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/2020-06-scenario-planning-pandemic-navigating-managing-uncertainty/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Goodspeed, R. Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions: Managing and Envisioning Uncertain Futures; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olgun, R.; Cheng, C.; Coseo, P. Nature-Based Solutions Scenario Planning for Climate Change Adaptation in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Land 2024, 13, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T.; Kliimask, J.; Kalm, K.; Zālīte, J. Did the Pandemic Bring New Features to Counter-Urbanisation? Evidence from Estonia. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsubo, M.; Nakaya, T. Trends in Internal Migration in Japan, 2012–2020: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incaltarau, C.; Kourtit, K.; Pascariu, G.C. Exploring the Urban-Rural Dichotomies in Post-Pandemic Migration Intention: Empirical Evidence from Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 111, 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, F.; Calafiore, A.; Arribas-Bel, D.; Samardzhiev, K.; Fleischmann, M. Urban Exodus? Understanding Human Mobility in Britain During the COVID-19 Pandemic Using Meta-Facebook Data. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Z.; Lang, W. Understanding Urban Growth and Shrinkage: A Study of the Modern Manufacturing City of Dongguan, China. Land 2025, 14, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN DESA (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs). International Migration 2020 Highlights. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/international_migration_2020_highlights_ten_key_messages.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Brouwer, A.E.; Mariotti, I. Remote Working and New Working Spaces During the COVID-19 Pandemic—Insights from EU and Abroad. In European Narratives on Remote Working and Coworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multidisciplinary Perspective; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- González-Leonardo, M.; Rowe, F.; Fresolone-Caparrós, A. Rural Revival? The Rise in Internal Migration to Rural Areas During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Who Moved and Where? J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidi, S.; Sabouri, S.; Ewing, R. Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic? Early Findings and Lessons for Planners. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2020, 86, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, C. Critical Commentary: Repopulating Density: COVID-19 and the Politics of Urban Value. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1548–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Compact Living or Policy Inaction? Effects of Urban Density and Lockdown on the COVID-19 Outbreak in the US. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1588–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, D. The Rural Migration Trend: What to Make of It, Why It’s Happening and Where It’s Headed. Available online: https://www.aem.org/news/the-rural-migration-trend-what-to-make-of-it-why-its-happening-and-where-its-headed (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Petersen, J.K.; Winkler, R.L.; Mockrin, M.H. Changes to Rural Migration in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rural Sociol. 2024, 89, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.L.; Petersen, J. Fewer People Are Moving Out of Rural Counties Since COVID-19. Amber Waves, 26 September 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, P.B.; Frost, W. Migration Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of New England Showing Movements down the Urban Hierarchy and Ensuing Impacts on Real Estate Markets. Prof. Geogr. 2023, 75, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumenti, N. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed Household Migration in New England. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Available online: https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/new-england-public-policy-center-regional-briefs/2021/how-the-covid-19-pandemic-changed-household-migration-in-new-england.aspx (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Kane, K. How Have American Migration Patterns Changed in the COVID Era? Growth Chang. 2024, 55, e12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C. Retaining Social and Cultural Sustainability in the Hudson River Watershed of New Yor, USA: A Place Based Participatory Action Research Study. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2022, 15, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevarez, L.; Simons, J. Small–City Dualism in the Metro Hinterland: The Racialized “Brooklynization” of New York’s Hudson Valley. City Community 2020, 19, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.; Tsai, T.-H. The Role of Amenities and Quality of Life in Rural Economic Growth. In Environmental Amenities and Regional Economic Development; Cherry, T., Rickman, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dimke, C.; Lee, M.C.; Bayham, J. COVID-19 and the Renewed Migration to the Rural West. West. Econ. Forum 2021, 19, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.A.; Rahe, M.L.; Van Leuven, A.J. Has COVID-19 Made Rural Areas More Attractive Places to Live? Survey Evidence from Northwest Missouri. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 520–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bański, J. Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland. Land 2025, 14, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Đoković, F.; Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Vukolić, D.; Mandarić, M.; Dašić, G.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Mićović, A. Pandemic Boosts Prospects for Recovery of Rural Tourism in Serbia. Land 2023, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F.; Castro, B. State-Led Tourism Infrastructure and Rural Regeneration: The Case of the Costa Da Morte Parador (Galicia, Spain). Land 2025, 14, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Dept. of Commerce; Bureau of the Census. County-to-County Migration Flows: 2016–2020 ACS. 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/geographic-mobility/county-to-county-migration-2016-2020.html (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Statistics of Income (SOI) Tax Stats—Migration Data. 2020. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-migration-data (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- U.S. Dept. of Commerce; Bureau of the Census. Decennial Census by Decade (1990, 2000, 2010, 2020). 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade.html (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Economic Research Service. Urban-Rural Continuum Codes. 2023. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA) Economics: National Ocean Watch (ENOW). Defining Coastal Counties. 2010. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/data/digitalcoast/pdf/defining-coastal-counties.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA Natural Amenities Scale. 2023. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/natural-amenities-scale (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- New NY Broadband Program. New York State. Available online: https://broadband.ny.gov/new-ny-broadband-program (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Marandi, A.; Main, K.L. Vulnerable City, recipient city, or climate destination? Towards a typology of domestic climate migration impacts in US cities. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 11, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, H.M.; Marchman, P. Integration as Adaptation: Advancing Research and Practice for Inclusive Climate Receiving Communities. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2024, 90, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

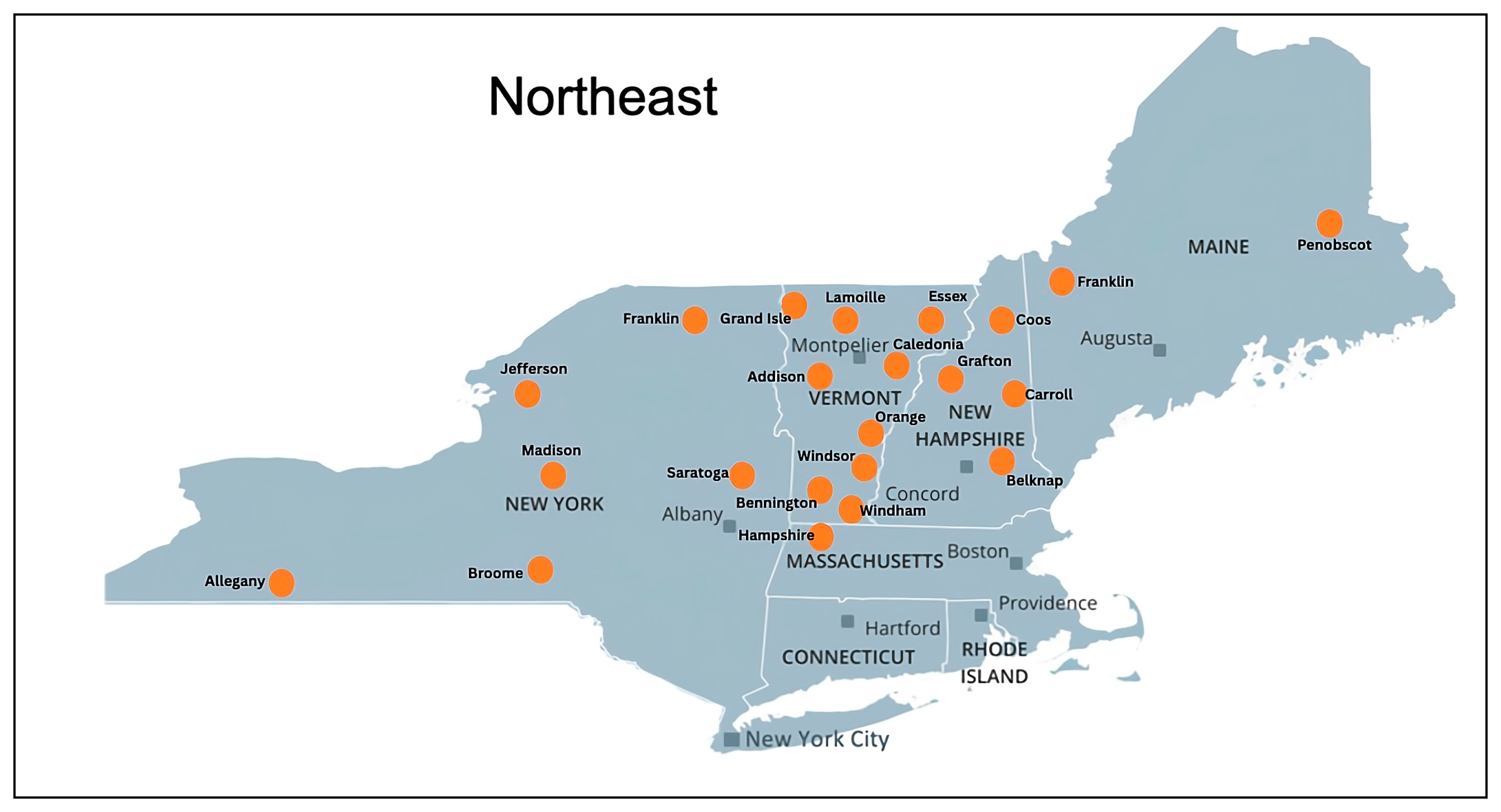

| State | County | Population (2020) [64] | Inflow Rate (%) [62,63] | Out-of-Region Inflow Within the Overall Inflow (%) [62,63] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | Hampshire | 162,308 | 10 | 17 |

| ME | Franklin | 29,456 | 9 | 15 |

| Penobscot | 152,199 | 6 | 25 | |

| NH | Grafton | 91,118 | 9 | 37 |

| Coos | 31,268 | 8 | 24 | |

| Belknap | 63,705 | 6 | 28 | |

| Carroll | 50,107 | 6 | 25 | |

| NY | Franklin | 47,555 | 9 | 15 |

| Jefferson | 116,721 | 9 | 66 | |

| Saratoga | 235,509 | 6 | 31 | |

| Allegany | 46,456 | 6 | 25 | |

| Broome | 198,683 | 5 | 25 | |

| Madison | 68,016 | 5 | 23 | |

| VT | Lamoille | 25,945 | 9 | 23 |

| Addison | 37,363 | 7 | 38 | |

| Essex | 5920 | 7 | 34 | |

| Bennington | 37,347 | 6 | 31 | |

| Caledonia | 30,233 | 6 | 24 | |

| Grand Isle | 7293 | 6 | 27 | |

| Windsor | 57,753 | 6 | 22 | |

| Orange | 29,277 | 6 | 24 | |

| Windham | 45,905 | 5 | 28 |

| State | Total Number of Participants from Each State | Number of State-Level Participants | County | Number of County-Level Participants | Number of Brokers | Number of Housing Experts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | 8 | Hampshire | 8 | 7 | 1 | |

| ME | 2 | 1 (State Housing Authority, ME) | Penobscot | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| NH | 3 | 1 (Workforce Housing Coalition of the Greater Seacoast, NH) | Grafton | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Belknap | 1 | 1 | ||||

| NY | 2 | Saratoga | 1 | 1 | ||

| Broome | 1 | 1 | ||||

| VT | 12 | 1 (Vermont Center for Geographic Information, VCGI) | Lamoille | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Caledonia | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Addison | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Grand Isle | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Windsor | 3 | 3 |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | States/Counties Reported on the Topic. (n: Number of Participants Reported on the Topic) | Total Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing-related challenges | Limited housing stock vs. increasing demand | Hampshire, MA (n = 8), Belknap, NH (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), NH (state) (n =1), ME (state) (n = 1), Penobscot, ME (n = 1), VT (state) (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 3), Lamoille, VT (n = 2), Windsor, VT (3), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1), Caledonia, VT (n = 2), Broome, NY (n = 1), Saratoga, NY (n = 1) | 27 (100%) |

| Lack of affordable housing options | Hampshire, MA (n = 8), Broome, NY (n = 1), Saratoga, NY (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1), ME (state) (n = 1), Penobscot, ME (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 3), Windsor, VT (n = 3), Lamoille, VT (n = 2), Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1), VT (state) (n = 1) | 26 (96%) | |

| Barriers to new development | Hampshire, MA (n = 7), Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Broome, NY (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1), ME (state) (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 3), Lamoille, VT (n = 2), Windsor, VT (n = 2), VT (state) (n = 1) | 21 (78%) | |

| Infrastructure- related challenges | Insufficient/aging infrastructure | Hampshire, MA (n = 5), Saratoga, NY (n = 1), Broome, NY (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), Penobscot, ME (n = 1), Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Windsor, VT (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 2), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1), Lamoille, VT (n = 1) | 15 (56%) |

| Insufficient social services | Hampshire, MA (n = 4), Saratoga, NY (n = 1), ME (state) (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 3), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1), Lamoille, VT (n = 1), Windsor, VT (n = 1) | 14 (52%) | |

| Socioeconomic challenges | Displacement & gentrification | Hampshire, MA (n = 4), Broome, NY (n = 1), ME (state) (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 2), Lamoille, VT (n = 2), Windsor, VT (n = 3), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1), VT (state) (n = 1) | 18 (67%) |

| Increasing homelessness | Hampshire, MA (n = 3), Penobscot, ME (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 2), Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Lamoille, VT (n = 1), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1) | 9 (33%) | |

| Lower adaptive capacity of low-income groups | Hampshire, MA (n = 5), Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Broome, NY (n = 1), Windsor, VT (n = 2), Grafton, NH (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 1), Lamoille, VT (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1) | 14 (52%) | |

| Lessons for regional planning | Balancing existing & emerging problems | Hampshire, MA (n = 7), Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Broome, NY (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 3), Windsor, VT (n = 2), Lamoille, VT (n = 1), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), ME (state) (n = 1) | 20 (74%) |

| Collaborating on communicating changes | Hampshire, MA (n = 6), Broome, NY (n = 1), Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Penobscot, ME (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 2), Lamoille, VT (n = 1), Windsor, VT (n = 1), VT (state) (n = 1), Grand Isle, VT (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), ME (state) (n = 1) | 19 (70%) | |

| Proactive planning with a timeframe | Caledonia, VT (n = 1), Hampshire, MA (n = 2), Penobscot, ME (n = 1), Addison, VT (n = 1), Lamoille, VT (n = 1), Grafton, NH (n = 1), NH (state) (n = 1), Belknap, NH (n = 1), ME (state) (n = 1), Windsor, VT (n = 1) | 11 (41%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kuru, O.D.; Infield, E.; Renski, H.; Shome, P.; Hodos, E. Population Mobility in the Wake of COVID-19 in the US Northeast Region: Lessons for Regional Planning. Land 2026, 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010003

Kuru OD, Infield E, Renski H, Shome P, Hodos E. Population Mobility in the Wake of COVID-19 in the US Northeast Region: Lessons for Regional Planning. Land. 2026; 15(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuru, Omur Damla, Elisabeth Infield, Henry Renski, Paromita Shome, and Emily Hodos. 2026. "Population Mobility in the Wake of COVID-19 in the US Northeast Region: Lessons for Regional Planning" Land 15, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010003

APA StyleKuru, O. D., Infield, E., Renski, H., Shome, P., & Hodos, E. (2026). Population Mobility in the Wake of COVID-19 in the US Northeast Region: Lessons for Regional Planning. Land, 15(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010003