Spatiotemporal Evolution and Scenario Simulation of Landscape Ecological Risk in Hilly–Gully Regions: A Case Study of Zichang City

Abstract

1. Introduction

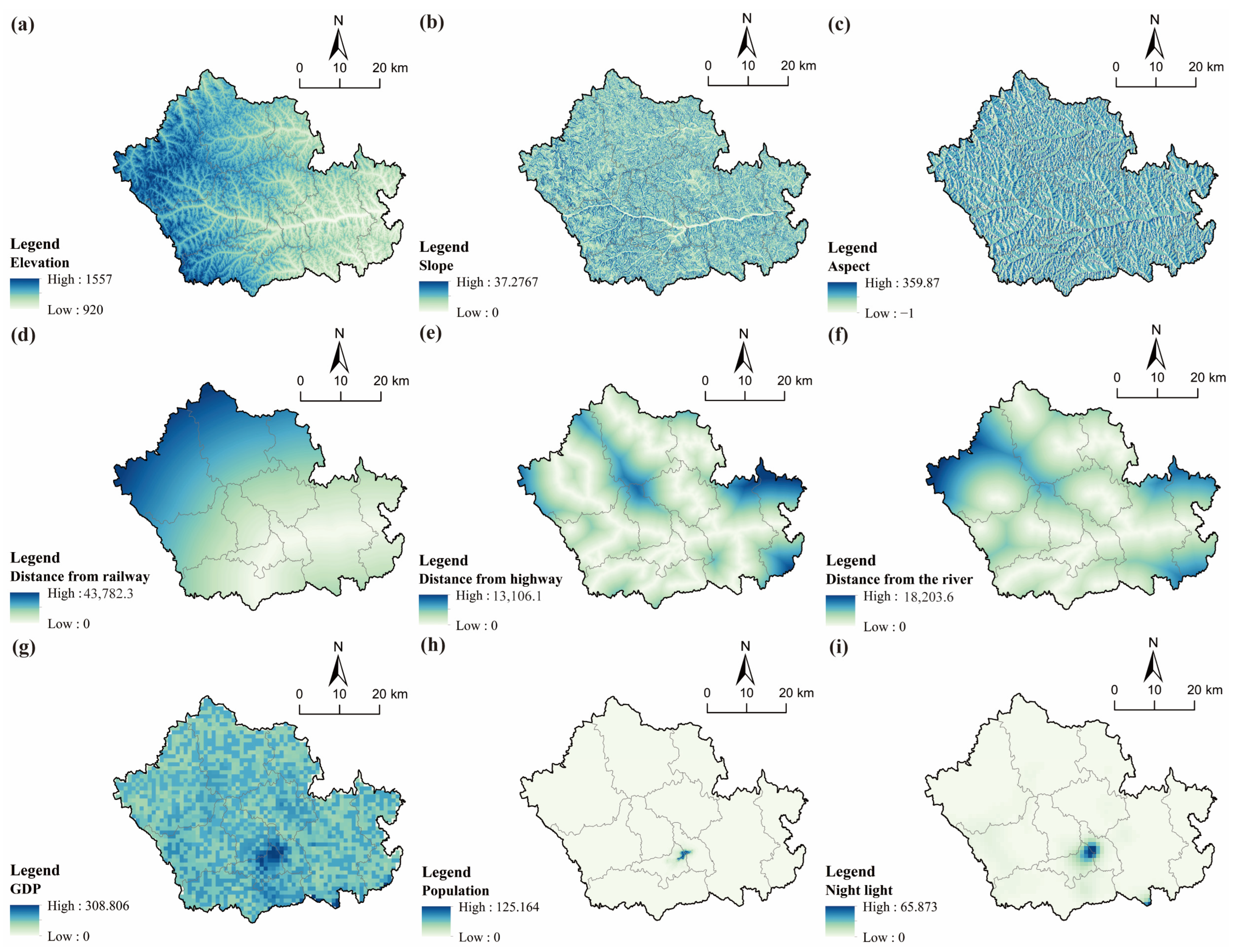

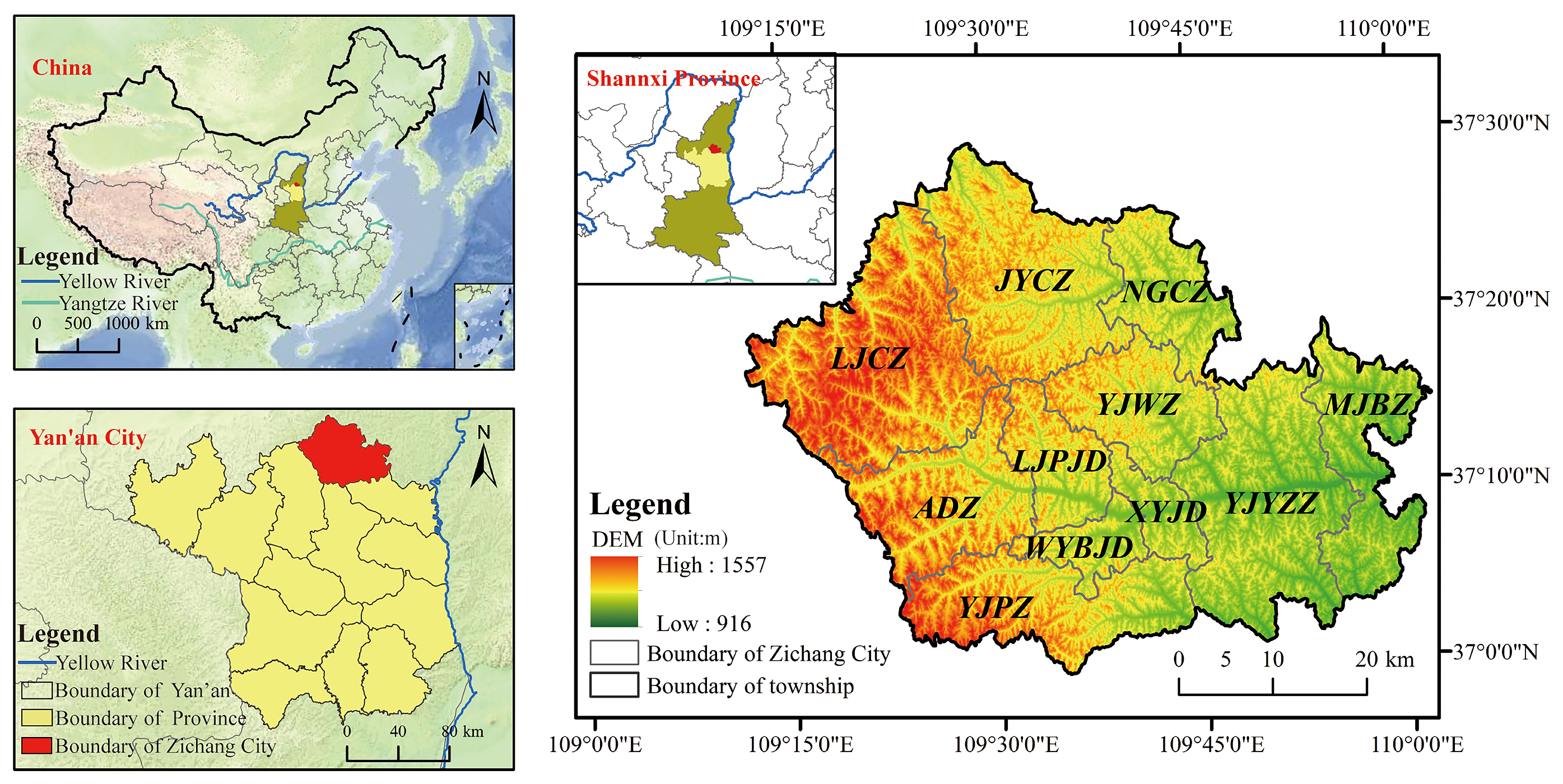

2. Research Area and Data Source

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

| Data | Sub-Data | Year(s) | Data Properties | Sources | Access Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land use dataset | Land use | 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, 2020 | Grids/30 m | https://www.resdc.cn/DOI/DOI.aspx?DOIID=5 [16] | Accessed on 20 November 2024 |

| Natural geography dataset | DEM | 2005 | Grids/30 m | https://www.gscloud.cn/sources/accessdata/310?pid=302 [21] | Accessed on 21 November 2024 |

| Water area | 2005 | Vector | https://data.casearth.cn/dataset/66580e10819aec3bf756e167 [22] | Accessed on 21 November 2024 | |

| Railways | 2005 | Vector | OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/) [23] | Accessed on 22 October 2024 | |

| Highways | 2005 | Vector | OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/) [23] | Accessed on 21 November 2024 | |

| Nighttime light data | 2005 | Grids/1000 m | https://www.resdc.cn/DOI/DOI.aspx?DOIID=105 [24] | Accessed on 22 November 2024 | |

| Socio-economic dataset | Population density | 2005 | Grids/1000 m | WorldPop (https://www.worldpop.org/) [25] | Accessed on 22 November 2024 |

| GDP | 2005 | Grids/1000 m | https://www.resdc.cn/DOI/DOI.aspx?DOIID=33 [26] | Accessed on 22 November 2024 |

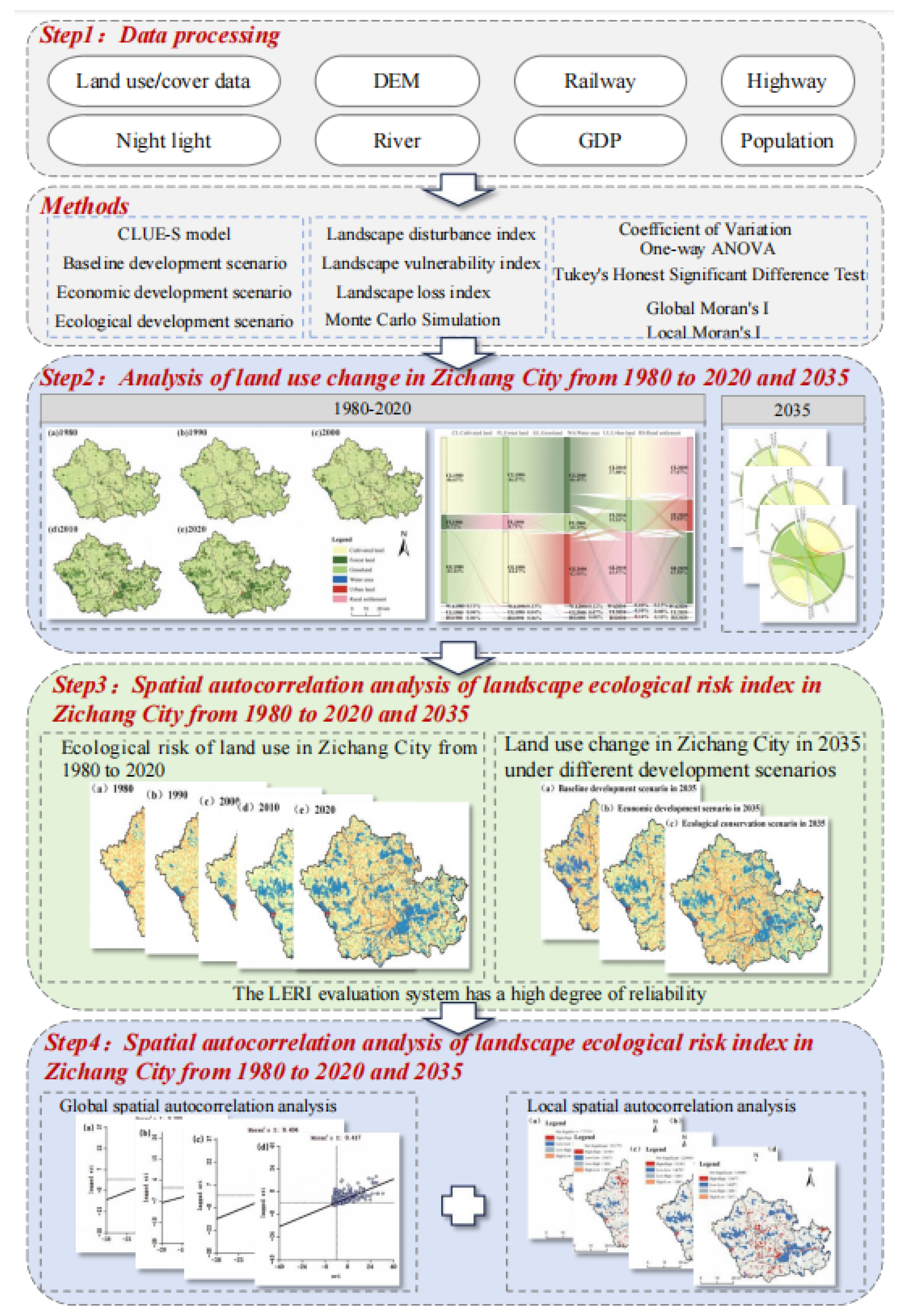

3. Methods

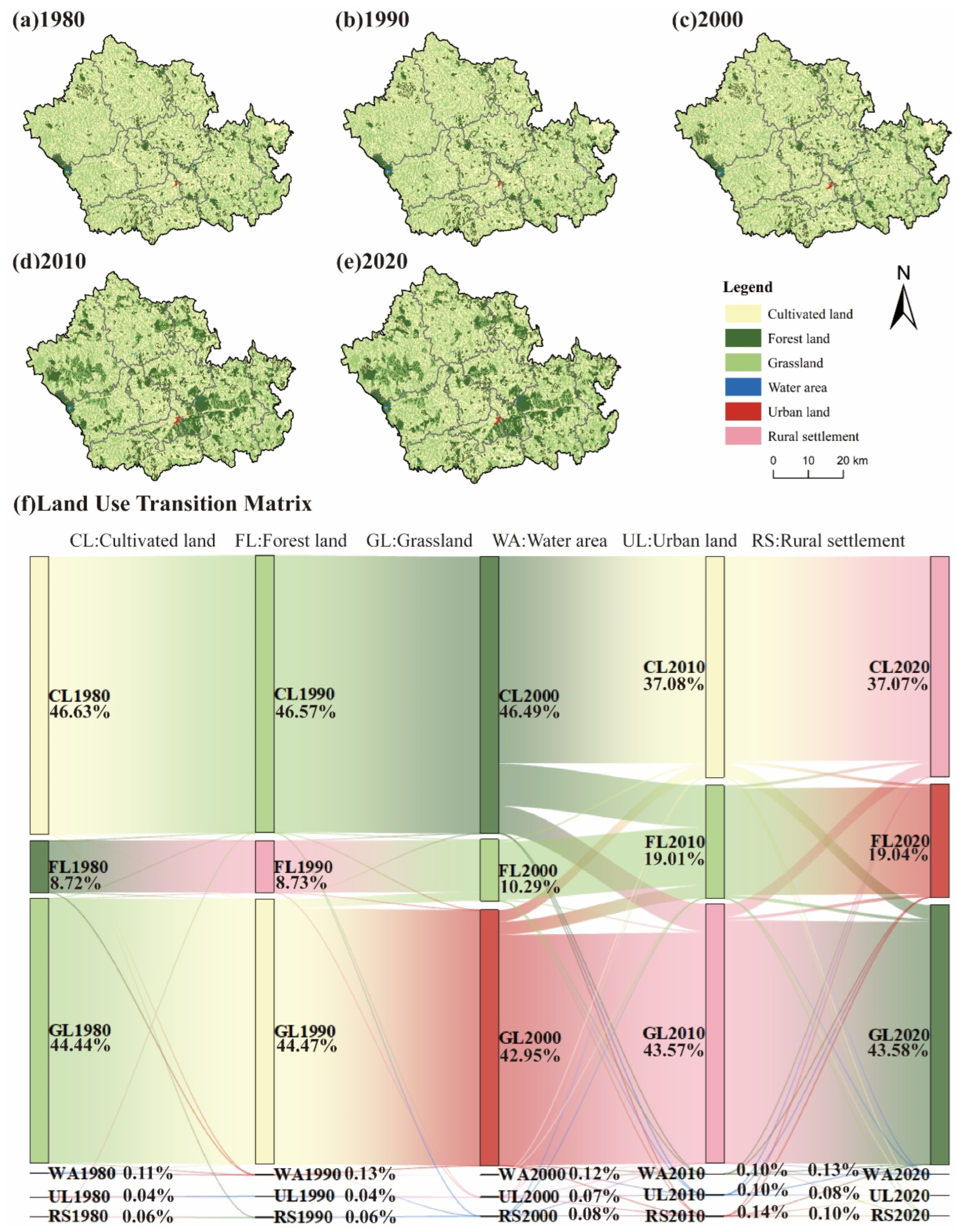

3.1. Land Use Transition Matrix

3.2. Land Use Change Simulation

3.2.1. CLUE-S Model and Accuracy Verification

- (1)

- CLUE-S Model

- (2)

- Accuracy Validation

3.2.2. Scenario Design

- (1)

- Baseline Development Scenario

- (2)

- Economic Development Scenario

- (3)

- Ecological Protection Scenario

3.3. Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment

3.3.1. Delineation of Ecological Risk Assessment Units

3.3.2. Landscape Ecological Risk Index

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- Landscape Vulnerability Index

- (6)

- Landscape Loss Index

- (7)

- Landscape Ecological Risk Index

- (8)

- Sensitivity Analysis of the Landscape Ecological Risk Index

3.4. One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Tukey HSD Post Hoc Test

3.5. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Land Use Change in Zichang City

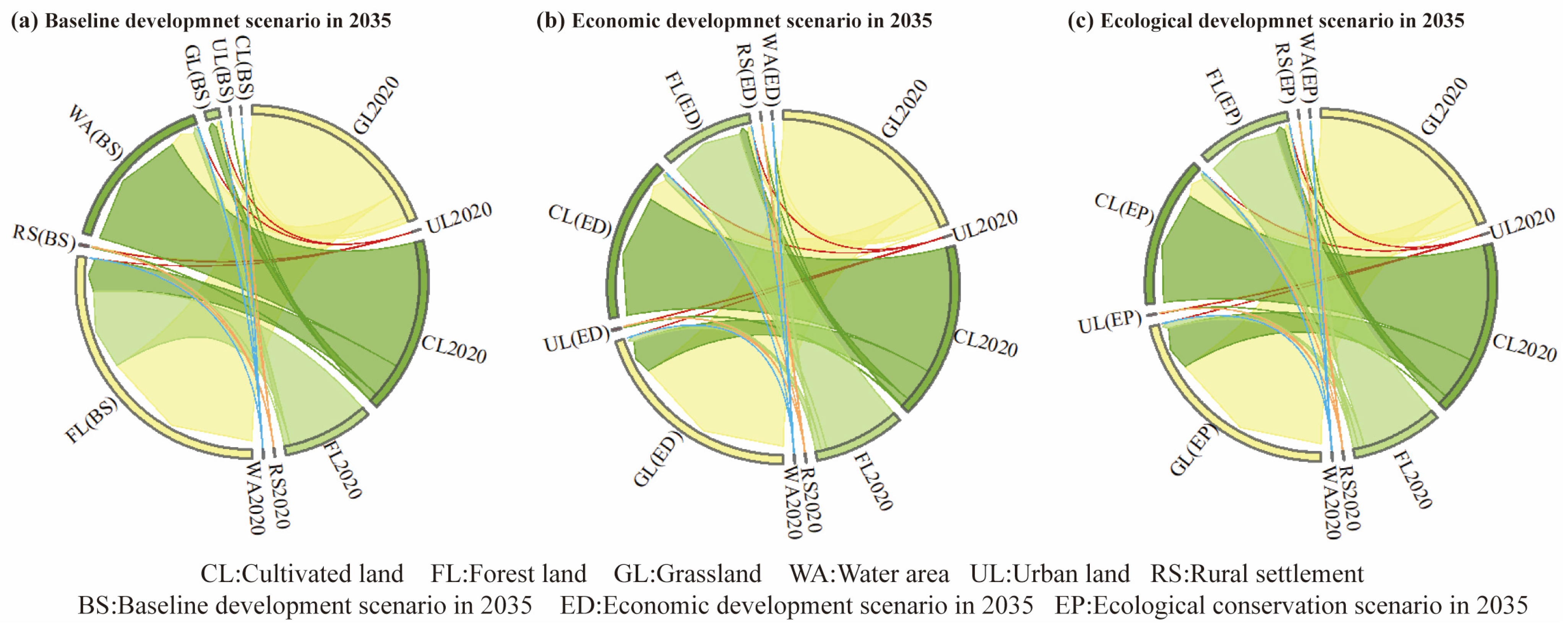

4.2. Land Use Dynamics Under Alternative Development Scenarios

4.2.1. Baseline Development Scenario

4.2.2. Economic Development Scenario

4.2.3. Ecological Protection Scenario

4.3. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Landscape Ecological Risk

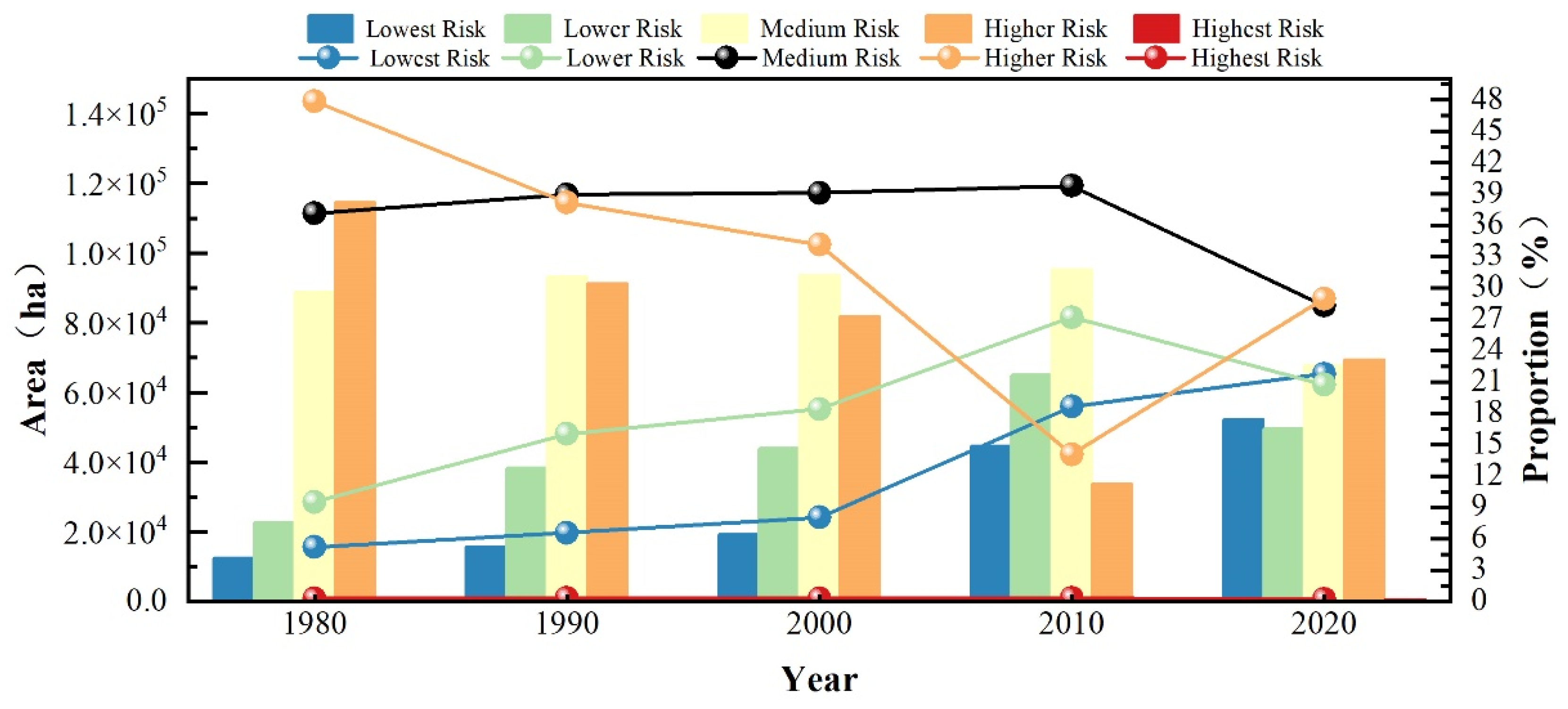

4.3.1. Temporal Evolution of Landscape Ecological Risk

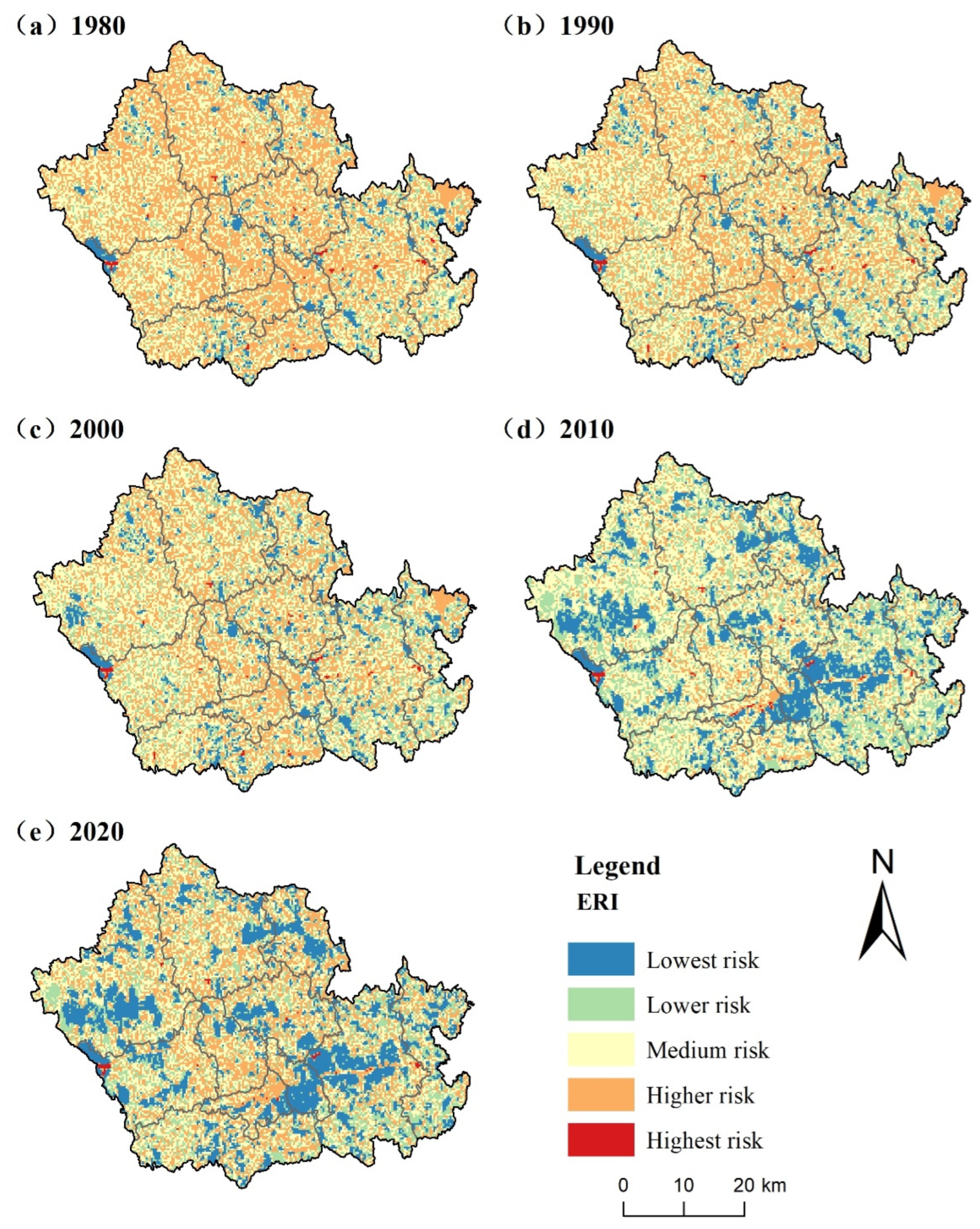

4.3.2. Spatial Differentiation of Landscape Ecological Risk

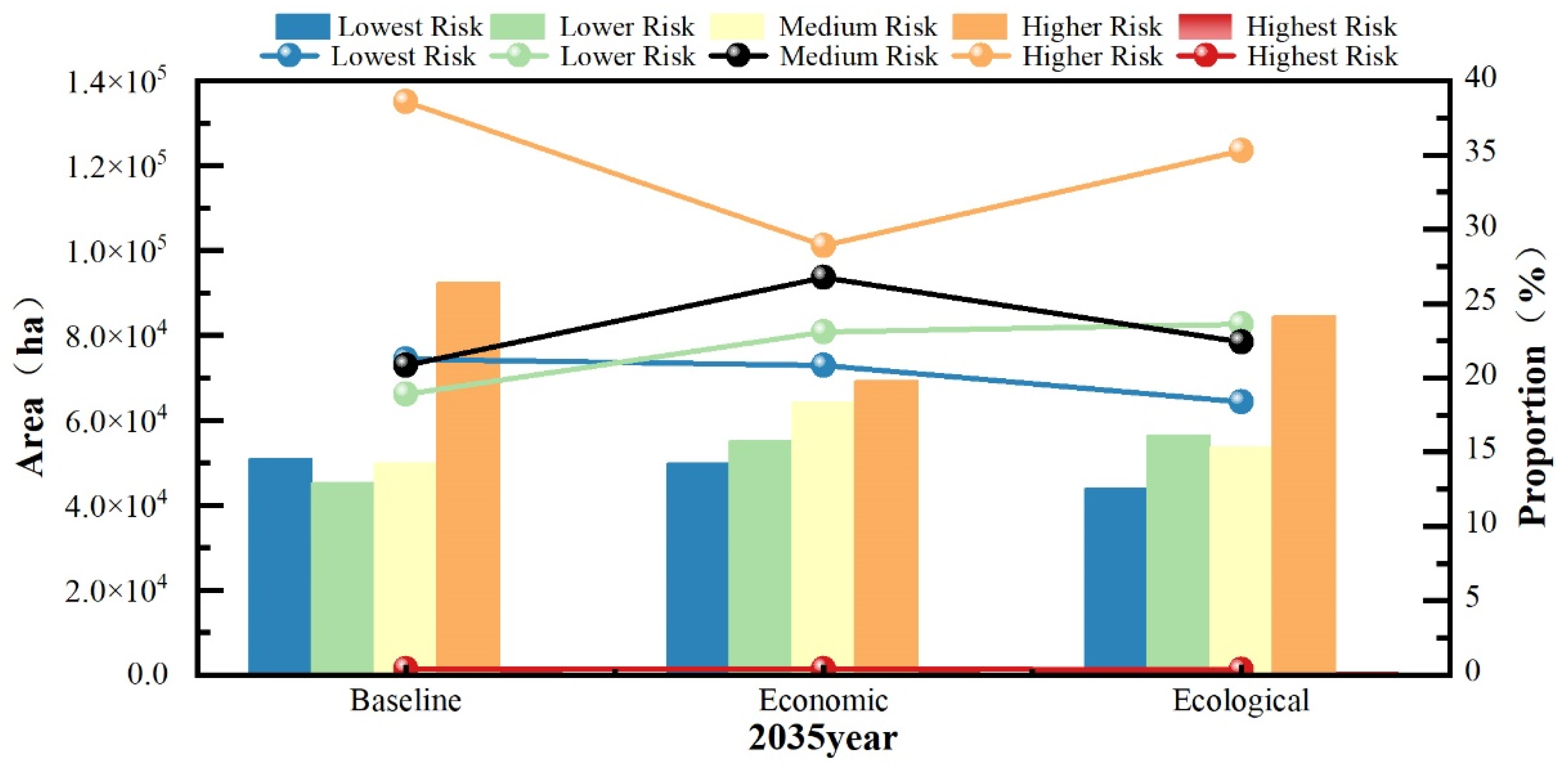

4.3.3. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Landscape Ecological Risk Under Different Scenarios

4.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis of the Landscape Ecological Risk Index

4.4. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis of Landscape Ecological Risk

4.4.1. Global Spatial Autocorrelation

4.4.2. Local Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Drivers of Landscape Ecological Risk Changes

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LER | Landscape ecological risk |

| LERI | Landscape Ecological Risk Index |

| ERI | Ecological Risk Index |

| LUCC | Land use/cover change |

| RS | remote sensing |

| GIS | geographic information systems |

| ABM | multi-agent modeling |

| CA | cellular automata |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| LISA | Local indicators of spatial association |

Appendix A

References

- Airiken, M.; Li, S. The Dynamic Monitoring and Driving Forces Analysis of Ecological Environment Quality in the Tibetan Plateau Based on the Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Chatterjee, N.D.; Dinda, S. Urban ecological security assessment and forecasting using integrated DEMATEL-ANP and CA-Markov models: A case study on Kolkata Metropolitan Area, India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, X.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Lu, Z.; Yue, R. To refine differential land use strategies by developing landscape risk assessment for urban agglomerations in the Yellow River Basin of China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 117, 108162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Shi, J.; Hu, X.; Yan, B. Temporal and spatial patterns of traditional village distribution evolution in Xiangxi, China: Identifying multidimensional influential factors and conservation significance. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masalvad, S.K.; Patil, C.; Vardhan, A.R.; Yadav, A.; Lavanya, B.; Sakare, P.K. Predicting land use changes and ecosystem service impacts with CA-Markov and machine learning techniques. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Song, W. Preferential encroachment of high-quality cropland by urban expansion across China: Past trends and future projections. Habitat Int. 2026, 167, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hameedi, W.M.M.; Chen, J.; Faichia, C.; Al-Shaibah, B.; Nath, B.; Kafy, A.-A.; Hu, G.; Al-Aizari, A. Remote Sensing-Based Urban Sprawl Modeling Using Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network Markov Chain in Baghdad, Iraq. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, C.; Lu, J. Understanding Spatiotemporal Development of Human Settlement in Hurricane-prone Areas on U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coasts using Nighttime Remote Sensing. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 2141–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayumba, P.M.; Chen, Y.; Mind’jE, R.; Mindje, M.; Li, X.; Maniraho, A.P.; Umugwaneza, A.; Uwamahoro, S. Geospatial land surface-based thermal scenarios for wetland ecological risk assessment and its landscape dynamics simulation in Bayanbulak Wetland, Northwestern China. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 1699–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, G. Human disturbance changes based on spatiotemporal heterogeneity of regional ecological vulnerability: A case study of Qiqihaer city, northwestern Songnen Plain, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Tian, L.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z. Ecological risk assessment and uncertainty analysis of the Yellow River basin based on probability-loss. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, H.; Zou, W.; Chen, Y.; Xia, J.; Wang, Z. Landscape ecological risk assessment and driving factor analysis in Dongjiang river watershed. Chemosphere 2024, 346, 140599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Khromykh, V.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Zhong, X. A landscape-based ecological hazard evaluation and characterization of influencing factors in Laos. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1276239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, B. Analyzing the influence of land use/land cover change on landscape pattern and ecosystem services in the Poyang Lake Region, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 27193–27206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuitjer, G.; Steinführer, A. The scientific construction of the village. Framing and practicing rural research in a trend study in Germany, 1952–2015. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, R.; La Sala, P.; De Pascale, G.; Faccilongo, N. The conservation of cultural heritage in rural areas: Stakeholder preferences regarding historical rural buildings in Apulia, southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Cai, J. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Future Scenario Simulation of the Trade-offs and Synergies of Mountain Ecosystem Services: A Case Study of the Dabie Mountains Area, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulaixi, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Dynamic Evolution and Scenario Simulation of Ecosystem Services under the Impact of Land-Use Change in an Arid Inland River Basin in Xinjiang, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, W. Coupling analysis of land use change with landscape ecological risk in China: A multi-scenario simulation perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyuan, L.I.; Huan, N.I.; Xiaonan, N.; Mengfan, F.; Yu, W.U.; Huan, F. Spatio-temporal Evolution and Future Multi-scenario Simulation of Land Use and Ecosystem Service Value in Fujian Delta Urban Agglomeration. Geogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M. Rural landscape, nature conservation and culture: Some notes on research trends and management approaches from a (southern) European perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 126, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai-Yin, C.; Shu-Yun, M. Heritage preservation and sustainability of China’s development. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 12, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachen, C.; Jinye, L. Thinking on the evolution path of the intangible cultural heritage protection system around the world. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Xue, Y.; Shang, C. Spatial distribution analysis and driving factors of traditional villages in Henan province: A comprehensive approach via geospatial techniques and statistical models. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, L. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Fujian Province, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qin, M.; Wu, X.; Luo, D.; Ouyang, H.; Liu, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of ecosystem service bundle based on multi-scenario simulation in Beibu Gulf ur-ban agglomeration, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, B.; Lu, S.; Gu, G.; Liu, Y. Evaluating the migration of boundary river shorelines and coastal land cover changes for the Beilun River between China and Vietnam. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artikanur, S.D.; Widiatmaka, W.; Setiawan, Y.; Marimin, M. Predicting Sugar Balance as the Impact of Land-Use/Land-Cover Change Dynamics in a Sugarcane Producing Regency in East Java, Indonesia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 787207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Duan, L.; Liritzis, I.; Li, J. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of intangible cultural heritage in the Yellow River Basin. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Huang, Z.; Liang, M.A.; Huang, J.; Zhou, G. Suitable granularity and response of multi-scale landscape in low mountain and hilly area of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 4703–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Fang, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Yu, Z. Spatiotemporal variation of alpine gorge watershed landscape patterns via multiscale metrics and optimal granularity analysis: A case study of Lushui City in Yunnan Province, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1448426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Che, X.; Wang, Z. Exploring new methods for assessing landscape ecological risk in key basin. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. Construction of landscape ecological network based on landscape ecological risk assessment in a large-scale opencast coal mine area. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X. Ecological risk assessment of watershed economic zones on the landscape scale: A case study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Reg. Environ. Change 2023, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kang, J.; Wang, Y. Integrating ecosystem services supply-demand balance into landscape ecological risk and its driving forces assessment in Southwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Optimization of landscape ecological risk assessment method and ecological management zoning considering resilience. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Meng, J.; You, N.; Chen, P.; Yang, H. Spatio-temporal Analysis of Anthropogenic Disturbances on Landscape Pattern of Tourist Destinations: A case study in the Li River Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gong, J.; Plaza, A.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Tao, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, S. Long-term assessment of ecological risk dynamics in Wuhan, China: Multi-perspective spatiotemporal variation analysis. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, C.P.; Fuller, A.K. Combining landscape variables and species traits can improve the utility of climate change vulnerability assessments. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 202, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Sokolov, A.; Reilly, J.; Libardoni, A.; Forest, C.; Paltsev, S.; Schlosser, C.A.; Prinn, R.; Jacoby, H. Quantifying both socioeconomic and climate uncertainty in coupled human–Earth systems analysis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarland, T.W. Oneway Analysis of Variance (ANOVA); Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Senay, D.; Nurlu, E. Spatio-temporal assessment of landscape ecological risk using spatial statistical analysis in a basin of Turkiye. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Im, J.; Park, S.; Cho, D. Thermal Characteristics of Daegu using Land Cover Data and Satellite-derived Surface Temperature Downscaled Based on Machine Learning. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2017, 33, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.H. Yimei Impacts of the Three-North shelter forest program on the main soil nutrients in Northern Shaanxi China: A meta-analysis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 458, 117808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongjian, Z.; Shuling, H.; Yuanyuan, W.; Jing’Ai, W.; Huicong, J. Multi-scales Analysis of Driving Forces on Land Use/Cover Change in China: Taking Farmland Returning to Forest or Grassland as a Case. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2006, 4, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council the People’s Republic of China. China’s Western Development Strategy to Gain New Momentum. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/policywatch/202005/28/content_WS5ecf2018c6d0b3f0e9498d45.html (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Yang, C.; Zhan, Q.; Gao, S.; Liu, H. Characterizing the spatial and temporal variation of the land surface temperature hotspots in Wuhan from a local scale. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 23, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Peng, Y.; Qin, W. Simulation, prediction and driving factor analysis of ecological risk in Savan District, Laos. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1058792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piech, I.; Dacko, A. Landscape unit as an element of digital cultural heritage: Theory and concepts on the example of Czuów. Geomat. Landmanag. Landsc. 2025, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. The Construction of the Landscape and Village-Integrated Green Governance System Based on the Entropy Method: A Study from China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Cost-benefit analysis of ecological restoration based on land use scenario simulation and ecosystem service on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 34, e02006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ding, J.; Zhao, W. Divergent responses of ecosystem services to afforestation and grassland restoration in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Yang, J.; Xie, F. The impact of ecological protection policies evolution on spatial-temporal changes: Evidence from Qiantang River Basin, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Pan, H.; Gan, J.; Sheng, S.; Lu, G. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Scenario Simulation of Landscape Ecological Risk in Hilly–Gully Regions: A Case Study of Zichang City. Land 2025, 14, 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122358

Zhang Z, Pan H, Gan J, Sheng S, Lu G. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Scenario Simulation of Landscape Ecological Risk in Hilly–Gully Regions: A Case Study of Zichang City. Land. 2025; 14(12):2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122358

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhongqian, Huanli Pan, Jing Gan, Shuangqing Sheng, and Guoyang Lu. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Evolution and Scenario Simulation of Landscape Ecological Risk in Hilly–Gully Regions: A Case Study of Zichang City" Land 14, no. 12: 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122358

APA StyleZhang, Z., Pan, H., Gan, J., Sheng, S., & Lu, G. (2025). Spatiotemporal Evolution and Scenario Simulation of Landscape Ecological Risk in Hilly–Gully Regions: A Case Study of Zichang City. Land, 14(12), 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122358