Permafrost Degradation: Mechanisms, Effects, and (Im)Possible Remediation

Abstract

1. Introduction: Permafrost and Ground Ice

2. Degradation Processes and Modelling

2.1. Processes

2.2. Modelling of Permafrost

- Thermo-hydraulic models focus on combined thermal flow and mass transfer within soils during freezing and thawing. They consider the variations and movement of unfrozen water content with temperature and are often validated against field observations of temperature and water content [82,83]. Phase change is generally managed using concepts such as apparent heat capacity or relative permeability [73].

- Thermo-mechanical models traditionally focus on phenomena such as frost heave and thaw settlement, which are closely related to changes in soil strength during the processes of freezing and thawing [84,85,86,87]. These models are founded on the principles of energy conservation and linear momentum equations, frequently simplifying the coupling to emphasise the impact of heat transfer on mechanical properties, such as those dependent on temperature. Additionally, certain thermo-mechanical models integrate water migration through the application of the segregation potential model.

- Thermo-hydro-mechanical (THM) models are capable of simulating the complex interactions among thermal, hydraulic, and mechanical fields within soil [88]. Early iterations of THM models commonly employed simplifying assumptions. However, more sophisticated models (e.g., capturing temperature and porosity dependence of shear strength) have been developed to investigate complex phenomena, such as soil-pipeline interactions and frost heaving processes, incorporating water migration [79,89,90,91,92]. In models concerning frozen soil, the thermal component addresses heat conduction and convection resulting from water movement. The hydraulic component models water transport driven by temperature, hydraulic gradients, and pressure variations, with permeability being dependent on temperature and pore pressure [93]. The mechanical component considers stresses induced by thermal expansion and volumetric changes attributable to ice formation, with elastic parameters related to temperature, saturation, and porosity [73]. These models often rely on stress fields governed by Navier’s equation, effective stress theory, poromechanics, and elastic or elastoplasticity theories [94,95,96,97,98]. A considerable number of models incorporate elastic-plastic constitutive relationships, such as the Modified Cam-Clay model or the Clay And Sand Model [99,100], to simulate soil hardening during freezing and softening or volume compression during thawing [91]. Additionally, some models introduce a pore ice content ratio to regulate hardening and softening behaviours [101,102]. Of particular interest are novel THM models that account for the formation and evolution of ice lenses [103], with criteria for their formation influenced by temperature, overburden pressure, separation strength, void ratio, and porosity.

- Thermo-hydro-chemical (THC) models incorporate the chemical component, particularly focusing on freezing point depression caused by solutes, which is especially relevant in fine-grained soils. They examine the effects of salt on freezing and thawing processes and the interactions between salination and freeze–thaw cycles [104,105,106].

- Thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical (THMC) models are comprehensive frameworks that examine the combined influences of thermal, hydraulic, mechanical, and chemical processes. Research in this field frequently explores the effect of salt on THM processes in frozen soils or during the dissociation and formation of natural gas hydrates [73,107,108].

- Phase-field modelling elucidates the macroscopic phase-change process and is augmented by the continuum theory of porous media. This modelling approach is efficacious in capturing microstructural evolution, discontinuities due to damage, granular rearrangement, and phase transitions in frozen soils [109]. Certain models employ two-phase field variables to simulate freezing-induced fractures resulting from ice lens formation. A recent study introduced a THM framework integrated with a phase-field methodology and adapted Cam-Clay plasticity to model thaw consolidation, thereby addressing issues of nonlocal softening and particle reorganisation [100].

- The Material Point Method (MPM) has recently been employed to model time-dependent phase transitions and large deformations in porous media, especially useful for thawing-triggered landslides and significant settlements, where the finite-element method might face mesh distortion [112]. This framework treats ice as a solid constituent and uses an ice saturation-dependent Mohr-Coulomb model for strength.

- Recent research also concentrates on scaling up thermal models from the pore level to the Darcy scale using numerical methods, deriving effective properties through homogenisation, and extending pore-scale physics to align with empirical Darcy-scale models. This includes integrating phenomena such as freezing temperature depression in small pores (Gibbs-Thomson relation) [113].

2.3. Permafrost Evolution from Climate Modelling

- RCP 8.5: High-emissions scenario, with a projected temperature increase in +8 °C;

- RCP 6.0: Medium–high-emissions scenario, with +4 °C;

- RCP 4.5: Medium–low-emissions scenario, with +3 °C;

- RCP 2.6: Low-emissions scenario, with +1.5 °C by 2100.

3. Consequences

3.1. Landslides

3.2. Foundations Design and Soil Properties

4. Remediation

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spiridonov, V.; Ćurić, M.; Novkovski, N. Hydrosphere and Cryosphere: Key Challenges. In Atmospheric Perspectives: Unveiling Earth’s Environmental Challenges; Spiridonov, V., Ćurić, M., Novkovski, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 83–105. ISBN 978-3-031-86757-6. [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann, S.; Knoflach, B.; Stötter, J.; Elsner, B.; Illmer, P.; Geitner, C. Potential Impacts of a Changing Cryosphere on Soils of the European Alps: A Review. CATENA 2023, 232, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.N. Earth’s Energy Balance and Climate. In Sustainable Energy and Environment; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-429-43010-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bibi, S.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, D.; Yao, T. Climatic and Associated Cryospheric, Biospheric, and Hydrological Changes on the Tibetan Plateau: A Review. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, e1–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábián, S.Á.; Kovács, J.; Varga, G.; Sipos, G.; Horváth, Z.; Thamó-Bozsó, E.; Tóth, G. Distribution of Relict Permafrost Features in the Pannonian Basin, Hungary. Boreas 2014, 43, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, A.; Hugelius, G.; Kuhry, P.; Christensen, T.R.; Vandenberghe, J. GIS-Based Maps and Area Estimates of Northern Hemisphere Permafrost Extent during the Last Glacial Maximum. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2016, 27, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Pei, W.; Melnikov, A.; Khristoforov, I.; Li, R.; Yu, F. Changes in Permafrost Extent and Active Layer Thickness in the Northern Hemisphere from 1969 to 2018. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobinski, W. Permafrost. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2011, 108, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisnås, K.; Etzelmüller, B.; Lussana, C.; Hjort, J.; Sannel, A.B.K.; Isaksen, K.; Westermann, S.; Kuhry, P.; Christiansen, H.H.; Frampton, A.; et al. Permafrost Map for Norway, Sweden and Finland. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2017, 28, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Zhao, L.; Sheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, G.; Wu, T.; Wu, J.; Xie, C.; Wu, X.; Pang, Q.; et al. A New Map of Permafrost Distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 2017, 11, 2527–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, J.; Moreiras, S.; Korup, O. Permafrost Activity and Atmospheric Warming in the Argentinian Andes. Geomorphology 2018, 323, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obu, J.; Westermann, S.; Bartsch, A.; Berdnikov, N.; Christiansen, H.H.; Dashtseren, A.; Delaloye, R.; Elberling, B.; Etzelmüller, B.; Kholodov, A.; et al. Northern Hemisphere Permafrost Map Based on TTOP Modelling for 2000–2016 at 1 km2 Scale. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 193, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overduin, P.P.; Schneider von Deimling, T.; Miesner, F.; Grigoriev, M.N.; Ruppel, C.; Vasiliev, A.; Lantuit, H.; Juhls, B.; Westermann, S. Submarine Permafrost Map in the Arctic Modeled Using 1-D Transient Heat Flux (SuPerMAP). J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 3490–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnov, A.; Smith, A.J.; Mienert, J.; Cherkashov, G.; Rekant, P.; Semenov, P.; Serov, P.; Vanshtein, B. Offshore Permafrost Decay and Massive Seabed Methane Escape in Water Depths >20 m at the South Kara Sea Shelf. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3962–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overduin, P.P.; Haberland, C.; Ryberg, T.; Kneier, F.; Jacobi, T.; Grigoriev, M.N.; Ohrnberger, M. Submarine Permafrost Depth from Ambient Seismic Noise. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 7581–7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throop, J.; Lewkowicz, A.G.; Smith, S.L. Climate and Ground Temperature Relations at Sites across the Continuous and Discontinuous Permafrost Zones, Northern Canada. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2012, 49, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellerer-Pirklbauer, A. Long-Term Monitoring of Sporadic Permafrost at the Eastern Margin of the European Alps (Hochreichart, Seckauer Tauern Range, Austria). Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2019, 30, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S.; Fleiner, R.; Guegan, E.; Panday, P.; Schmid, M.-O.; Stumm, D.; Wester, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L. Review Article: Inferring Permafrost and Permafrost Thaw in the Mountains of the Hindu Kush Himalaya Region. Cryosphere 2017, 11, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljedahl, A.K.; Boike, J.; Daanen, R.P.; Fedorov, A.N.; Frost, G.V.; Grosse, G.; Hinzman, L.D.; Iijma, Y.; Jorgenson, J.C.; Matveyeva, N.; et al. Pan-Arctic Ice-Wedge Degradation in Warming Permafrost and Its Influence on Tundra Hydrology. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidov, N.; Wetterich, S.; Verkulich, S.; Ekaykin, A.; Meyer, H.; Anisimov, M.; Schirrmeister, L.; Demidov, V.; Hodson, A.J. Geochemical Signatures of Pingo Ice and Its Origin in Grøndalen, West Spitsbergen. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 3155–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuur, E.A.G.; McGuire, A.D.; Schädel, C.; Grosse, G.; Harden, J.W.; Hayes, D.J.; Hugelius, G.; Koven, C.D.; Kuhry, P.; Lawrence, D.M.; et al. Climate Change and the Permafrost Carbon Feedback. Nature 2015, 520, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblauch, C.; Beer, C.; Liebner, S.; Grigoriev, M.N.; Pfeiffer, E.-M. Methane Production as Key to the Greenhouse Gas Budget of Thawing Permafrost. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, M.; Ji, X.; Xiao, M.; Farquharson, L.; Nicolsky, D.; Romanovsky, V.; Bray, M.; Zhang, X.; McComb, C. Synthesis of Physical Processes of Permafrost Degradation and Geophysical and Geomechanical Properties of Permafrost. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 198, 103522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulombe, S.; Fortier, D.; Lacelle, D.; Kanevskiy, M.; Shur, Y. Origin, Burial and Preservation of Late Pleistocene-Age Glacier Ice in Arctic Permafrost (Bylot Island, NU, Canada). Cryosphere 2019, 13, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turetsky, M.R.; Abbott, B.W.; Jones, M.C.; Anthony, K.W.; Olefeldt, D.; Schuur, E.A.G.; Grosse, G.; Kuhry, P.; Hugelius, G.; Koven, C.; et al. Carbon Release through Abrupt Permafrost Thaw. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, H.; Fuchs, M.; Abbott, B.W.; Douglas, T.A.; Elder, C.D.; Ernakovich, J.G.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Göckede, M.; Grosse, G.; Hugelius, G.; et al. A Review of Abrupt Permafrost Thaw: Definitions, Usage, and a Proposed Conceptual Framework. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2025, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minsley, B.J.; Pastick, N.J.; James, S.R.; Brown, D.R.N.; Wylie, B.K.; Kass, M.A.; Romanovsky, V.E. Rapid and Gradual Permafrost Thaw: A Tale of Two Sites. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streletskiy, D.; Anisimov, O.; Vasiliev, A. Chapter 10—Permafrost Degradation. In Snow and Ice-Related Hazards, Risks, and Disasters; Shroder, J.F., Haeberli, W., Whiteman, C., Eds.; Hazards and Disasters Series; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 303–344. ISBN 978-0-12-394849-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, Z.A.; Riley, W.J.; Grant, R.F.; Romanovsky, V.E. Changes in Precipitation and Air Temperature Contribute Comparably to Permafrost Degradation in a Warmer Climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolsky, D.J.; Romanovsky, V.E. Modeling Long-Term Permafrost Degradation. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2018, 123, 1756–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, H.B.; Roy-Leveillee, P.; Lebedeva, L.; Ling, F. Recent Advances (2010–2019) in the Study of Taliks. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2020, 31, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streletskiy, D.A.; Maslakov, A.; Grosse, G.; Shiklomanov, N.I.; Farquharson, L.; Zwieback, S.; Iwahana, G.; Bartsch, A.; Liu, L.; Strozzi, T.; et al. Thawing Permafrost Is Subsiding in the Northern Hemisphere—Review and Perspectives. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 013006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewkowicz, A.G.; Way, R.G. Extremes of Summer Climate Trigger Thousands of Thermokarst Landslides in a High Arctic Environment. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, F.E.; Anisimov, O.A.; Shiklomanov, N.I. Subsidence Risk from Thawing Permafrost. Nature 2001, 410, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shur, Y.L.; Jorgenson, M.T. Patterns of Permafrost Formation and Degradation in Relation to Climate and Ecosystems. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2007, 18, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ou, Y.H.; Xu, X.; Zhao, L.; Song, M.; Zhou, C. Effects of Permafrost Degradation on Ecosystems. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shur, Y.; Goering, D.J. Climate Change and Foundations of Buildings in Permafrost Regions. In Permafrost Soils; Margesin, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 251–260. ISBN 978-3-540-69371-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dourado, J.B.d.O.L.; Deng, L.; Chen, Y.; Chui, Y.-H. Foundations in Permafrost of Northern Canada: Review of Geotechnical Considerations in Current Practice and Design Examples. Geotechnics 2024, 4, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Niu, F.; Lin, Z.; Liu, M.; Yin, G. Recent Acceleration of Thaw Slumping in Permafrost Terrain of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: An Example from the Beiluhe Region. Geomorphology 2019, 341, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Trubl, G.; Taş, N.; Jansson, J.K. Permafrost as a Potential Pathogen Reservoir. One Earth 2022, 5, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-Y.; Jin, H.-J.; Iwahana, G.; Marchenko, S.S.; Luo, D.-L.; Li, X.-Y.; Liang, S.-H. Impacts of Climate-Induced Permafrost Degradation on Vegetation: A Review. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 12, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhuang, Q.; O’Donnell, J.A. Modeling Thermal Dynamics of Active Layer Soils and Near-Surface Permafrost Using a Fully Coupled Water and Heat Transport Model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D11110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, R.; Hu, J.; Wen, L.; Feng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q. InSAR Analysis of Surface Deformation over Permafrost to Estimate Active Layer Thickness Based on One-Dimensional Heat Transfer Model of Soils. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, G.L.; O’Brien, D.; Webster, P.J.; Pilewski, P.; Kato, S.; Li, J. The Albedo of Earth. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Jin, H.; Marchenko, S.S.; Romanovsky, V.E. Difference between Near-Surface Air, Land Surface and Ground Surface Temperatures and Their Influences on the Frozen Ground on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geoderma 2018, 312, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, M.; Douglas, T.; Racine, C.; Liston, G.E. Changing Snow and Shrub Conditions Affect Albedo with Global Implications. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2005, 110, G01004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ma, M.; Wu, X.; Yang, H. Snow Cover and Vegetation-Induced Decrease in Global Albedo From 2002 to 2016. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Gao, J.H.; Wang, Y.Q.; Quan, X.J.; Gong, Y.W.; Zhou, S.W. Experimental Study on the Effect of Freezing and Thawing on the Shear Strength of the Frozen Soil in Qinghai-Tibet Railway Embankment. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9239460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmera, B.; Emami Ahari, H. Review of the Impact of Permafrost Thawing on the Strength of Soils. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 2024, 38, 03124001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Unfrozen Water Content of Permafrost during Thawing by the Capacitance Technique. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 152, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenbrod, K.D.; Knutsson, S.; Sheng, D. Pore-Water Pressures in Freezing and Thawing Fine-Grained Soils. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 1996, 10, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walvoord, M.A.; Kurylyk, B.L. Hydrologic Impacts of Thawing Permafrost—A Review. Vadose Zone J. 2016, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; Yang, C. Investigation on the Effects of Freeze-Thaw Action on the Pore Water Pressure Variations of Soils. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2018, 140, 062001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yao, X.; Yu, F.; Liu, Y. Study on Thaw Consolidation of Permafrost under Roadway Embankment. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2012, 81, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yao, X.; Yu, F. Consolidation of Thawing Permafrost Considering Phase Change. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2013, 17, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; You, Y. A Consolidation Model for Estimating the Settlement of Warm Permafrost. Comput. Geotech. 2016, 76, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoie, É.; Connon, R.F.; Beddoe, R.; Goordial, J.; Quinton, W.L.; Craig, J.R. Disconnected Active Layers and Unfrozen Permafrost: A Discussion of Permafrost-Related Terms and Definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connon, R.; Devoie, É.; Hayashi, M.; Veness, T.; Quinton, W. The Influence of Shallow Taliks on Permafrost Thaw and Active Layer Dynamics in Subarctic Canada. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2018, 123, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, S.; Jin, R. Thermal Regimes and Degradation Modes of Permafrost along the Qinghai-Tibet Highway. Sci. China Ser. D 2006, 49, 1170–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.-H.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Zhang, S.-H.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Dong, T.-C.; Wang, J.-C.; Zhao, Y.-J. Degradation of Warm Permafrost and Talik Formation on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau in 2006–2021. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2024, 15, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Cao, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Chou, Y.; Wu, J.; Peng, E. The Evolution Process and Degradation Model of Permafrost in the Source Area of the Yellow River on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau since the Little Ice Age. CATENA 2024, 236, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, T.; Clow, G.D.; Sun, Y.-H.; Zhao, W.-Y.; Liang, B.-B.; Fan, C.-Y.; Peng, X.-Q.; Cao, B. Observed Permafrost Thawing and Disappearance near the Altitudinal Limit of Permafrost in the Qilian Mountains. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2022, 13, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, C. Heat Transport Processes in the Earth’s Crust. Surv. Geophys. 2009, 30, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, D. A Review of the Importance of Regional Groundwater Advection for Ground Heat Exchange. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 2555–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobiński, W.; Kasprzak, M. Permafrost Base Degradation: Characteristics and Unknown Thread with Specific Example from Hornsund, Svalbard. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 802157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.M.; Baughman, C.A.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Parsekian, A.D.; Babcock, E.L.; Stephani, E.; Jones, M.C.; Grosse, G.; Berg, E.E. Presence of Rapidly Degrading Permafrost Plateaus in South-Central Alaska. Cryosphere 2016, 10, 2673–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, M.T.; Douglas, T.A.; Liljedahl, A.K.; Roth, J.E.; Cater, T.C.; Davis, W.A.; Frost, G.V.; Miller, P.F.; Racine, C.H. The Roles of Climate Extremes, Ecological Succession, and Hydrology in Repeated Permafrost Aggradation and Degradation in Fens on the Tanana Flats, Alaska. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2020, 125, e2020JG005824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.C.P.; Nitzbon, J.; Scheer, J.; Aas, K.S.; Eiken, T.; Langer, M.; Filhol, S.; Etzelmüller, B.; Westermann, S. Lateral Thermokarst Patterns in Permafrost Peat Plateaus in Northern Norway. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 3423–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Barreda-Bautista, B.; Boyd, D.S.; Ledger, M.; Siewert, M.B.; Chandler, C.; Bradley, A.V.; Gee, D.; Large, D.J.; Olofsson, J.; Sowter, A.; et al. Towards a Monitoring Approach for Understanding Permafrost Degradation and Linked Subsidence in Arctic Peatlands. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creel, R.; Guimond, J.; Jones, B.M.; Nielsen, D.M.; Bristol, E.; Tweedie, C.E.; Overduin, P.P. Permafrost Thaw Subsidence, Sea-Level Rise, and Erosion Are Transforming Alaska’s Arctic Coastal Zone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2409411121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riseborough, D.; Shiklomanov, N.; Etzelmüller, B.; Gruber, S.; Marchenko, S. Recent advances in permafrost modelling. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2008, 19, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; O’Neill, H.B.; Isaksen, K.; Noetzli, J.; Romanovsky, V.E. The Changing Thermal State of Permafrost. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-Q.; Yin, Z.-Y. State of the Art of Coupled Thermo–Hydro-Mechanical–Chemical Modelling for Frozen Soils. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 1039–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yi, Y.; Yang, K.; Zhao, L.; Chen, D.; Kimball, J.S.; Lu, F. Soil Freeze/Thaw Dynamics Strongly Influences Runoff Regime in a Tibetan Permafrost Watershed: Insights from a Process-Based Model. CATENA 2024, 243, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, S.A. Numerical Modeling of the Freezing, Frost Heaving, and Thawing of Soils. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2004, 41, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S.; Hoelzle, M. Statistical modelling of mountain permafrost distribution: Local calibration and incorporation of remotely sensed data. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2001, 12, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckli, L.; Brenning, A.; Gruber, S.; Noetzli, J. A Statistical Approach to Modelling Permafrost Distribution in the European Alps or Similar Mountain Ranges. Cryosphere 2012, 6, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, T.; Wang, P.; Li, R.; Xie, C.; Zou, D. Spatial Distribution and Changes of Permafrost on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Revealed by Statistical Models during the Period of 1980 to 2010. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Gens, A.; Olivella, S.; Jardine, R.J. THM-Coupled Finite Element Analysis of Frozen Soil: Formulation and Application. Geotechnique 2009, 59, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarov, E.; Marchenko, S.; Romanovsky, V. Numerical Modeling of Permafrost Dynamics in Alaska Using a High Spatial Resolution Dataset. Cryosphere 2012, 6, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Sheng, Y.; Cao, W.; Ning, Z.; Tian, M.; Wang, Y. Thermal Stability Prediction of Frozen Rocks under Fluctuant Airflow Temperature in a Vertical Shaft Based on Finite Difference and Finite Element Methods. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 52, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, X. Coupled Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Model for Porous Materials under Frost Action: Theory and Implementation. Acta Geotech. 2011, 6, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, X. Coupled Thermo-Hydraulic Modelling of Pavement under Frost. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2014, 15, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamot, P.; Weber, S.; Eppinger, S.; Krautblatter, M. A Temperature-Dependent Mechanical Model to Assess the Stability of Degrading Permafrost Rock Slopes. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2021, 9, 1125–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Dong, J.; He, P.; Lian, B.; Wang, L. Thermo-Mechanical Evaluation of a Thermal Anchor Pipe Frame System for Permafrost Slope Stabilization. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2025, 43, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Lai, Y.; Jin, L. Thermo-Mechanical Stability Analysis of Cooling Embankment with Crushed-Rock Interlayer on a Sloping Ground in Permafrost Regions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 125, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Pei, W.; Li, S.; Lu, J.; Jin, L. Experimental and Numerical Analyses of the Thermo-Mechanical Stability of an Embankment with Shady and Sunny Slopes in a Permafrost Region. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 127, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaringi, G.; Loche, M. A Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Approach to Soil Slope Stability under Climate Change. Geomorphology 2022, 401, 108108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Guo, P.; Lai, Y.; Stolle, D. Frost Heave and Thaw Consolidation Modelling. Part 2: One-Dimensional Thermohydromechanical (THM) Framework. Can. Geotech. J. 2020, 57, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Ren, X.; Li, Z.; Li, G. Numerical Analysis of Frost Heave and Thawing Settlement of the Pile–Soil System in Degraded Permafrost Region. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cai, G.; Zhou, C.; Yang, R.; Li, J. Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Coupled Model of Unsaturated Frozen Soil Considering Frost Heave and Thaw Settlement. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 217, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Xiao, K.; Hao, Y.; Jin, L.; Wei, Y.; Tan, X. Moisture Migration within the Melting Laps during Construction Controls Frost Heaving Damage of Lining in Permafrost Tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 167, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Osada, Y. Simultaneous Measurement of Unfrozen Water Content and Hydraulic Conductivity of Partially Frozen Soil near 0 °C. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 142, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Lai, Y. Thermo-Poromechanics-Based Viscoplastic Damage Constitutive Model for Saturated Frozen Soil. Int. J. Plast. 2020, 128, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhou, A. A Multisurface Elastoplastic Model for Frozen Soil. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 3401–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, E.; Zhang, D.; Yue, P.; Wang, P.; Kang, J.; Yu, Q. An Elasto-Plastic Constitutive Model for Frozen Soil Subjected to Cyclic Loading. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 189, 103341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Liu, E.; Song, B.; Wang, P.; Wang, D.; Kang, J. A Poromechanics-Based Constitutive Model for Warm Frozen Soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 199, 103555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Norouzi, E.; Zhu, H.-H.; Wu, B. A Thermo-Poromechanical Model for Simulating Freeze–Thaw Actions in Unsaturated Soils. Adv. Water Resour. 2024, 184, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Guo, P.; Na, S. A Framework for Constructing Elasto-Plastic Constitutive Models for Frozen and Unfrozen Soils. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2022, 46, 436–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebria, M.M.; Na, S.; Tighe, S. Thermo-Hydro-Mechanics of Thawing Permafrost: A Phase-Field Framework with Enriched Modified Cam-Clay Plasticity. Acta Geotech. 2025, 20, 4329–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Teng, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Cai, G.; Sheng, D. A New Strength Criterion for Frozen Soil Considering Pore Ice Content. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04022107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wen, D. Pore Microstructure and Mechanical Behaviour of Frozen Soils Subjected to Variable Temperature. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 206, 103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ghoreishian Amiri, S.A.; Kjelstrup, S.; Grimstad, G.; Loranger, B.; Scibilia, E. Formation and Growth of Multiple, Distinct Ice Lenses in Frost Heave. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2023, 47, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, J.; Tan, X.; Huang, J.; Jansson, P.-E.; Zhang, W. Simulation of Dynamical Interactions between Soil Freezing/Thawing and Salinization for Improving Water Management in Cold/Arid Agricultural Region. Geoderma 2019, 338, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Bian, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. Assessment of Future Climate Change Impacts on Water-Heat-Salt Migration in Unsaturated Frozen Soil Using CoupModel. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Ren, D.; Huang, G. Improving Soil Hydrological Simulation under Freeze–Thaw Conditions by Considering Soil Deformation and Its Impact on Soil Hydrothermal Properties. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimoto, S.; Oka, F.; Fushita, T. A Chemo–Thermo–Mechanically Coupled Analysis of Ground Deformation Induced by Gas Hydrate Dissociation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2010, 52, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Yu, T.; Wang, G.; Wang, W. Numerical Study on the Multifield Mathematical Coupled Model of Hydraulic-Thermal-Salt-Mechanical in Saturated Freezing Saline Soil. Int. J. Geomech. 2018, 18, 04018064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweidan, A.H.; Heider, Y.; Markert, B. A Unified Water/Ice Kinematics Approach for Phase-Field Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Modeling of Frost Action in Porous Media. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2020, 372, 113358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabakhanji, R.; Mohtar, R.H. A Peridynamic Model of Flow in Porous Media. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 78, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, P.; Sedighi, M.; Jivkov, A.P.; Margetts, L. Analysis of Heat Transfer and Water Flow with Phase Change in Saturated Porous Media by Bond-Based Peridynamics. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 185, 122327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, S.; Liang, W. Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Coupled Material Point Method for Modeling Freezing and Thawing of Porous Media. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2024, 48, 3308–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, N. Mathematical Models and Computational Schemes for Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Phenomena in Permafrost: Multiple Scales and Robust Solvers. Ph.D. Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler, L.; Peszynska, M.; Vohra, N. Heterogeneous Stefan Problem and Permafrost Models with P0-P0 Finite Elements and Fully Implicit Monolithic Solver. Electron. Res. Arch. 2022, 30, 1477–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, A.A.; Drozdov, D.S.; Gravis, A.G.; Malkova, G.V.; Nyland, K.E.; Streletskiy, D.A. Permafrost Degradation in the Western Russian Arctic. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, C.; Wu, T.; Zhao, L.; Pang, Q.; Wu, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, W.; Zhu, X.; Wu, X.; et al. Permafrost Degradation Is Accelerating beneath the Bottom of Yanhu Lake in the Hoh Xil, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y. Accelerated Permafrost Degradation in Thermokarst Landforms in Qilian Mountains from 2007 to 2020 Observed by SBAS-InSAR. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.H.; Zhang, W.; Hollesen, J.; Cable, S.; Christiansen, H.H.; Jansson, P.-E.; Elberling, B. Modelling Present and Future Permafrost Thermal Regimes in Northeast Greenland. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 146, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debolskiy, M.V.; Nicolsky, D.J.; Hock, R.; Romanovsky, V.E. Modeling Present and Future Permafrost Distribution at the Seward Peninsula, Alaska. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2020, 125, e2019JF005355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzbon, J.; Westermann, S.; Langer, M.; Martin, L.C.P.; Strauss, J.; Laboor, S.; Boike, J. Fast Response of Cold Ice-Rich Permafrost in Northeast Siberia to a Warming Climate. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.; Nitzbon, J.; Groenke, B.; Assmann, L.-M.; Schneider von Deimling, T.; Stuenzi, S.M.; Westermann, S. The Evolution of Arctic Permafrost over the Last 3 Centuries from Ensemble Simulations with the CryoGridLite Permafrost Model. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.M.; Slater, A.G. A Projection of Severe Near-Surface Permafrost Degradation during the 21st Century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L24401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchenko, P.F.; Eliseev, A.V.; Arzhanov, M.M.; Mokhov, I.I. Impact of Global Warming Rate on Permafrost Degradation. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2006, 42, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Sun, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Romanovsky, V.E. Attribution of Historical Near-Surface Permafrost Degradation to Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 084040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, H. CMIP5 Permafrost Degradation Projection: A Comparison among Different Regions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 4499–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, E.J.; Zhang, Y.; Krinner, G. Evaluating Permafrost Physics in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6 (CMIP6) Models and Their Sensitivity to Climate Change. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 3155–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, G.A.; Ginzburg, V.A.; Insarov, G.E.; Romanovskaya, A.A. CMIP6 Model Projections Leave No Room for Permafrost to Persist in Western Siberia under the SSP5-8.5 Scenario. Clim. Change 2021, 169, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Y. Effects of a Thaw Slump on Active Layer in Permafrost Regions with the Comparison of Effects of Thermokarst Lakes on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, China. Geoderma 2018, 314, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicu, I.C.; Lombardo, L.; Rubensdotter, L. Preliminary Assessment of Thaw Slump Hazard to Arctic Cultural Heritage in Nordenskiöld Land, Svalbard. Landslides 2021, 18, 2935–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makopoulou, E.; Karjalainen, O.; Elia, L.; Blais-Stevens, A.; Lantz, T.; Lipovsky, P.; Lombardo, L.; Nicu, I.C.; Rubensdotter, L.; Rudy, A.C.A.; et al. Retrogressive Thaw Slump Susceptibility in the Northern Hemisphere Permafrost Region. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 3319–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeberli, W.; Schaub, Y.; Huggel, C. Increasing Risks Related to Landslides from Degrading Permafrost into New Lakes in De-Glaciating Mountain Ranges. Geomorphology 2017, 293, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.I.; Rathburn, S.L.; Capps, D.M. Landslide Response to Climate Change in Permafrost Regions. Geomorphology 2019, 340, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loche, M.; Scaringi, G. Temperature and Shear-Rate Effects in Two Pure Clays: Possible Implications for Clay Landslides. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loche, M.; Scaringi, G. Assessing the Influence of Temperature on Slope Stability in a Temperate Climate: A Nationwide Spatial Probability Analysis in Italy. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 183, 106217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, O.P.; Loche, M.; Dahal, R.K.; Scaringi, G. Influence of Temperature on the Residual Shear Strength of Landslide Soil: Role of the Clay Fraction. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennevig, K.; Keiding, M.; Korsgaard, N.J.; Lucas, A.; Owen, M.; Poulsen, M.D.; Priebe, J.; Sørensen, E.V.; Morino, C. Uncovering a 70-Year-Old Permafrost Degradation Induced Disaster in the Arctic, the 1952 Niiortuut Landslide-Tsunami in Central West Greenland. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kääb, A.; Huggel, C.; Fischer, L.; Guex, S.; Paul, F.; Roer, I.; Salzmann, N.; Schlaefli, S.; Schmutz, K.; Schneider, D.; et al. Remote Sensing of Glacier- and Permafrost-Related Hazards in High Mountains: An Overview. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2005, 5, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjort, J.; Karjalainen, O.; Aalto, J.; Westermann, S.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Nelson, F.E.; Etzelmüller, B.; Luoto, M. Degrading Permafrost Puts Arctic Infrastructure at Risk by Mid-Century. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjort, J.; Streletskiy, D.; Doré, G.; Wu, Q.; Bjella, K.; Luoto, M. Impacts of Permafrost Degradation on Infrastructure. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Cheng, G.; Dong, Y.; Hjort, J.; Lovecraft, A.L.; Kang, S.; Tan, M.; Li, X. Permafrost Degradation Increases Risk and Large Future Costs of Infrastructure on the Third Pole. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergili, M.; Jaboyedoff, M.; Pullarello, J.; Pudasaini, S.P. Back Calculation of the 2017 Piz Cengalo–Bondo Landslide Cascade with r.Avaflow: What We Can Do and What We Can Learn. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungr, O.; Leroueil, S.; Picarelli, L. The Varnes Classification of Landslide Types, an Update. Landslides 2014, 11, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froude, M.J.; Petley, D.N. Global Fatal Landslide Occurrence 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhou, C.; Ng, C.W.W.; Tang, C.S. Effects of Soil Structure on Thermal Softening of Yield Stress. Eng. Geol. 2020, 269, 105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotta Loria, A.F.; Coulibaly, J.B. Thermally Induced Deformation of Soils: A Critical Overview of Phenomena, Challenges and Opportunities. Geomech. Energy Environ. 2021, 25, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, K.; Miller, R.D. Hydraulic conductivity functions of frozen materials. In Permafrost: Fourth International Conference; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Li, D.; Chen, J.; Xu, A.; Huang, S. Experimental Research on Physical-Mechanical Characteristics of Frozen Soil Based on Ultrasonic Technique. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Permafrost, Fairbanks, AK, USA, 29 June–3 July 2008; Volume 2, pp. 1179–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, M.; Kim, Y.C.; Park, J.B. The influence of temperature and cycles on acoustic and mechanical properties of frozen soils. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2009, 13, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Arnold, R. Acoustic properties of frozen Ottawa sand. Water Resour. Res. 1973, 9, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, R.W.; King, M.S. The effect of the extent of freezing on seismic velocities in unconsolidated permafrost. Geophysics 1986, 51, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Chae, D.; Kim, K.; Cho, W. Physical and mechanical characteristics of frozen ground at various sub-zero temperatures. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 20, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Experimental and Numerical Study of Sonic Wave Propagation in Freezing Sand and Silt; University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2009; ISBN 1-109-33815-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.Y.; Fossum, A.; Costin, L.S.; Bronowski, D. Frozen Soil Material Testing and Constitutive Modeling; Sandia Report; SAND: Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2002; Volume 524, pp. 8–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, Z.; Still, B.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Zubeck, H.; Petersen, T.; Aleshire, L. Elastic properties of saline permafrost during thawing by bender elements and bending disks. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 146, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, W.; Niu, Y. Application of Ultrasonic Technology for Physical–Mechanical Properties of Frozen Soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2006, 44, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, C. Strength and Yield Criteria of Frozen Soil. Prog. Nat. Sci. 1995, 5, 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Still, B.; Ge, X. Mechanical Properties of Seasonally Frozen and Permafrost Soils at High Strain Rate. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2015, 113, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, E.; Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Song, B. A New Strength Criterion for Frozen Soils Considering the Influence of Temperature and Coarse-Grained Contents. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 143, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

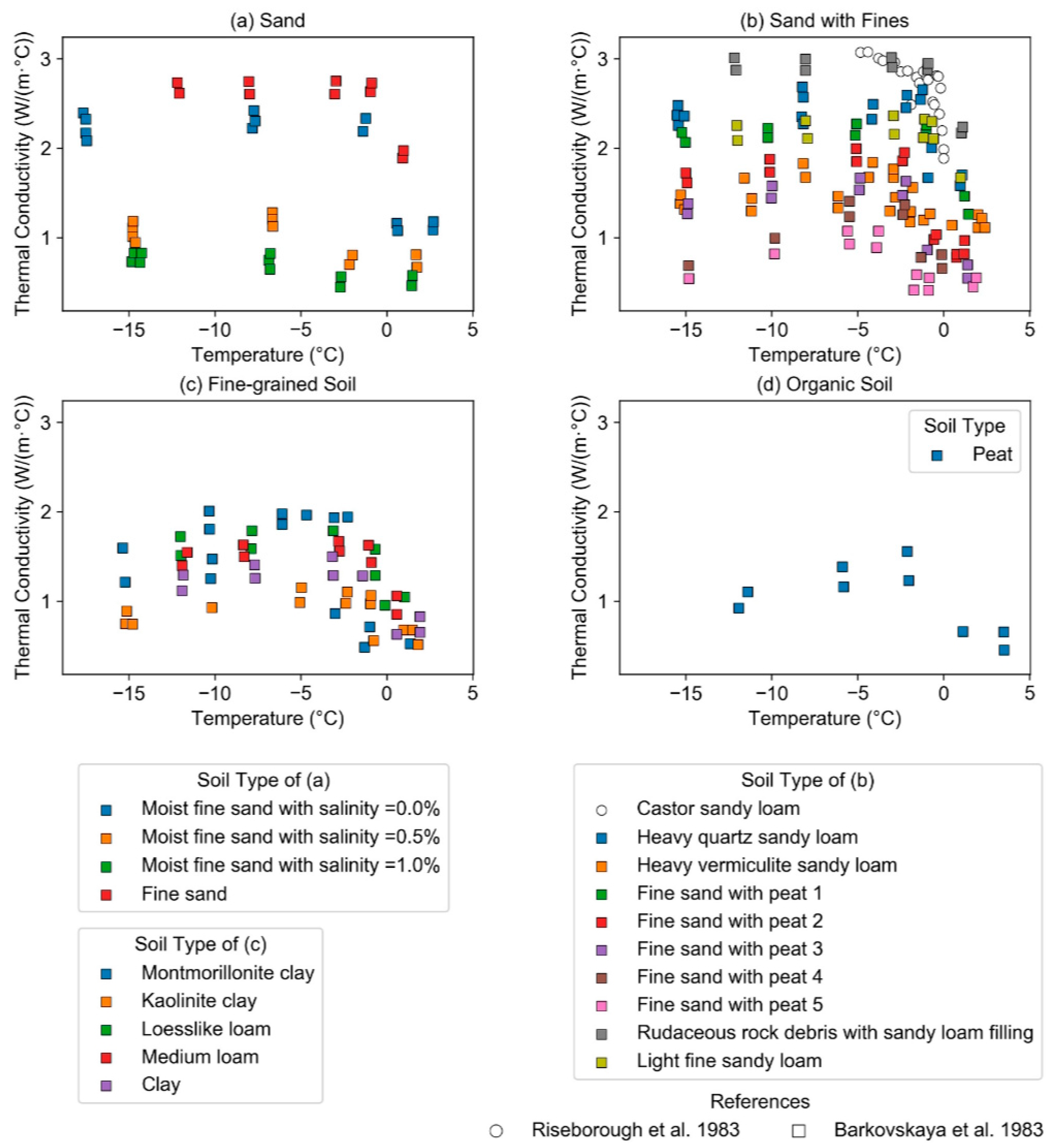

- Li, R.; Zhao, L.; Wu, T.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Yao, J.; Wu, X.; Hu, G.; Xiao, Y.; Du, Y.; et al. Soil Thermal Conductivity and Its Influencing Factors at the Tanggula Permafrost Region on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 264, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.-Q.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Chen, J.-B.; Dong, Y.-H.; Jin, L.; Peng, H. Experimental Test and Prediction Model of Soil Thermal Conductivity in Permafrost Regions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Weng, B.; Yan, D.; Lai, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, H. Underestimated Permafrost Degradation: Improving the TTOP Model Based on Soil Thermal Conductivity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, X.; Wang, W.; Niu, F.; Gao, Z. Investigating Soil Properties and Their Effects on Freeze-Thaw Processes in a Thermokarst Lake Region of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Eng. Geol. 2024, 342, 107734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riseborough, D.W.; Smith, M.W.; Halliwell, D.H. Determination of the thermal properties of frozen soils. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Permafrost, Fairbanks, AK, USA, 17–22 July 1983; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; pp. 1072–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Barkovskaya, Y.N.; Yershov, E.D.; Kamarove, I.A.; Cheveriov, V.G. Mechansism and regularities of changes in heat conductivity of soils during the freezing-thawing process. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Permafrost, Fairbanks, AK, USA, 17–22 July 1983; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, B.D.; Andersland, O.B. The Effect of Confining Pressure on the Mechanical Properties of Sand–Ice Materials. J. Glaciol. 1973, 12, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.A.H. Load Transfer and Creep Behavior of Pile Foundations in Frozen Soils. Ph.D. Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, C.B.; Johnston, G.H. Construction on Permafrost. Can. Geotech. J. 1971, 8, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Guodong, C.; Qingbai, W. Construction on Permafrost Foundations: Lessons Learned from the Qinghai–Tibet Railroad. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulitsky, V.M.; Gorodnova, E.V. The Construction of Transport Infrastructure on Permafrost Soils. Procedia Eng. 2017, 189, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, F.; Ma, W.; Fortier, R.; Mu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Mao, Y.; Cai, Y. Field Observations of Cooling Performance of Thermosyphons on Permafrost under the China-Russia Crude Oil Pipeline. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 141, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinfei, D.; Shengyue, W.; Shuangjie, W.; Jianbing, C. Cooling Permafrost Embankment by Enhancing Oriented Heat Conduction in Asphalt Pavement. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 103, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Niu, F.; Liu, M.; Lin, Z.; Yin, G. Field Experimental Study on Long-Term Cooling and Deformation Characteristics of Crushed-Rock Revetment Embankment at the Qinghai–Tibet Railway. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 139, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhou, G.; Chao, D.; Yin, L. Influence of Hydration Heat on Stochastic Thermal Regime of Frozen Soil Foundation Considering Spatial Variability of Thermal Parameters. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 142, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loktionov, E.Y.; Sharaborova, E.S.; Shepitko, T.V. A Sustainable Concept for Permafrost Thermal Stabilization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Doré, G.; Calmels, F. Thermal Modeling of Heat Balance through Embankments in Permafrost Regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 158, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X. Development of Design Tools for Convection Mitigation Techniques to Preserve Permafrost under Northern Transportation Infrastructure. Ph.D. Thesis, Laval University, Québec, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Wang, G.; Yu, Q.; Li, G.; Ma, W.; Zhao, S. Thermal Performance of a Combined Cooling Method of Thermosyphons and Insulation Boards for Tower Foundation Soils along the Qinghai–Tibet Power Transmission Line. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2016, 121, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, Y.; Bao, T. An Experimental Study of Reflective Shading Devices for Cooling Roadbeds in Permafrost Regions. Sol. Energy 2020, 205, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, C.; Zimov, N.; Olofsson, J.; Porada, P.; Zimov, S. Protection of Permafrost Soils from Thawing by Increasing Herbivore Density. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asanov, I.M.; Loktionov, E.Y. Possible Benefits from PV Modules Integration in Railroad Linear Structures. Renew. Energy Focus 2018, 25, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Liu, J.; Hao, Z.; Chang, J. Design and Experimental Study of a Solar Compression Refrigeration Apparatus (SCRA) for Embankment Engineering in Permafrost Regions. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 22, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimond, J.A.; Mohammed, A.A.; Walvoord, M.A.; Bense, V.F.; Kurylyk, B.L. Saltwater Intrusion Intensifies Coastal Permafrost Thaw. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL094776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.M.; Grosse, G.; Farquharson, L.M.; Roy-Léveillée, P.; Veremeeva, A.; Kanevskiy, M.Z.; Gaglioti, B.V.; Breen, A.L.; Parsekian, A.D.; Ulrich, M.; et al. Lake and Drained Lake Basin Systems in Lowland Permafrost Regions. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, T.C. Modelling Biome-Scale Root Reinforcement and Slope Stability. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2018, 43, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, G.; Fan, X.; Scaringi, G.; van Asch, T.W.; Xu, Q.; Huang, R.; Hales, T.C. Modelling the Role of Material Depletion, Grain Coarsening and Revegetation in Debris Flow Occurrences after the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Eng. Geol. 2019, 250, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedone, G.; Tsiampousi, A.; Cotecchia, F.; Zdravkovic, L. Coupled Hydro-Mechanical Modelling of Soil–Vegetation–Atmosphere Interaction in Natural Clay Slopes. Can. Geotech. J. 2022, 59, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva Subramanian, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Tokoro, T. Stability Assessment Approach for Soil Slopes in Seasonal Cold Regions. Eng. Geol. 2017, 221, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.S.; Fan, X.; Yunus, A.P.; van Asch, T.; Scaringi, G.; Xu, Q.; Dai, L.; Ishikawa, T.; Huang, R. A Sequentially Coupled Catchment-Scale Numerical Model for Snowmelt-Induced Soil Slope Instabilities. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2020, 125, e2019JF005468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommer, C.; Phillips, M.; Arenson, L.U. Practical Recommendations for Planning, Constructing and Maintaining Infrastructure in Mountain Permafrost. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2010, 21, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doré, G.; Niu, F.; Brooks, H. Adaptation Methods for Transportation Infrastructure Built on Degrading Permafrost. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2016, 27, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schädel, C.; Bader, M.K.-F.; Schuur, E.A.G.; Biasi, C.; Bracho, R.; Čapek, P.; De Baets, S.; Diáková, K.; Ernakovich, J.; Estop-Aragones, C.; et al. Potential Carbon Emissions Dominated by Carbon Dioxide from Thawed Permafrost Soils. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyagina, O.V.; Evgrafova, S.; Bugaenko, T.N.; Kholodilova, V.V.; Krivobokov, L.V.; Korets, M.A.; Wagner, D. Permafrost Landslides Promote Soil CO2 Emission and Hinder C Accumulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, K.R.; Turetsky, M.R.; Malina, E.; Bartsch, A.; Tamminen, J.; McGuire, A.D.; Fix, A.; Sweeney, C.; Elder, C.D.; Miller, C.E. Permafrost Carbon Emissions in a Changing Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, K.R.; D’Andrilli, J.; Mackelprang, R.; Edwards, A.; Malaska, M.J.; Waldrop, M.P.; Miller, C.E. Emergent Biogeochemical Risks from Arctic Permafrost Degradation. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, W.; Chen, T.; et al. Shift in Potential Pathogenic Bacteria during Permafrost Degradation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, C.M.; McCalley, C.K.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Boyd, J.A.; Evans, P.N.; Hodgkins, S.B.; Chanton, J.P.; Frolking, S.; Crill, P.M.; Saleska, S.R.; et al. Methanotrophy across a Natural Permafrost Thaw Environment. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2544–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, P.J.; Xie, S.; Clarke, W.P. Methane as a Resource: Can the Methanotrophs Add Value? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4001–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, C. Application and Development of Methanotrophs in Environmental Engineering. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2019, 21, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuschnig, C.; Larose, C.; Rudner, M.; Pesqueda, A.; Doleac, S.; Elberling, B.; Björk, R.G.; Klemedtsson, L.; Björkman, M.P. Reduced Methane Emissions in Former Permafrost Soils Driven by Vegetation and Microbial Changes Following Drainage. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 3411–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Possinger, A. Removal of Atmospheric CO2 by Rock Weathering Holds Promise for Mitigating Climate Change. Nature 2020, 583, 204–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gíslason, S.R.; Sigurdardóttir, H.; Aradóttir, E.S.; Oelkers, E.H. A Brief History of CarbFix: Challenges and Victories of the Project’s Pilot Phase. Energy Procedia 2018, 146, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratouis, T.M.P.; Snæbjörnsdóttir, S.Ó.; Voigt, M.J.; Sigfússon, B.; Gunnarsson, G.; Aradóttir, E.S.; Hjörleifsdóttir, V. Carbfix 2: A Transport Model of Long-Term CO2 and H2S Injection into Basaltic Rocks at Hellisheidi, SW-Iceland. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 114, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.H. Stopping and Reversing Climate Change. Resonance 2019, 24, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scafetta, N. Impacts and Risks of “Realistic” Global Warming Projections for the 21st Century. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feklistov, V.N.; Rusakov, N.L. Application of Foam Insulation for Remediation of Degraded Permafrost. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 1996, 24, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Wang, H.; Hou, X.; He, L. Direct Shooting Method-Based Optimized Design of Novel Bridge-like Pavement Structures. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2913, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tian, Y. Numerical Studies for the Thermal Regime of a Roadbed with Insulation on Permafrost. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2002, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Naterer, G.F. Thermal Protection of a Ground Layer with Phase Change Materials. J. Heat Transf. 2009, 132, 011301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Y. Application of a New Thermal Insulation Layer to Subgrade. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Transp. 2018, 175, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, S.; Fortier, D.; Sliger, M.; Rioux, K. Air-Convection-Reflective Sheds: A Mitigation Technique That Stopped Degradation and Promoted Permafrost Recovery under the Alaska Highway, South-Western Yukon, Canada. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 197, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Xu, T.; Xu, Z.; Wang, T.; Yin, L.; Jia, X.; Tang, J. Trends of Precipitation Acidification and Determining Factors in China During 2006–2015. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD031301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baillarget, D.; Scaringi, G. Permafrost Degradation: Mechanisms, Effects, and (Im)Possible Remediation. Land 2025, 14, 1949. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101949

Baillarget D, Scaringi G. Permafrost Degradation: Mechanisms, Effects, and (Im)Possible Remediation. Land. 2025; 14(10):1949. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101949

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaillarget, Doriane, and Gianvito Scaringi. 2025. "Permafrost Degradation: Mechanisms, Effects, and (Im)Possible Remediation" Land 14, no. 10: 1949. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101949

APA StyleBaillarget, D., & Scaringi, G. (2025). Permafrost Degradation: Mechanisms, Effects, and (Im)Possible Remediation. Land, 14(10), 1949. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101949