Socially-Tolerated Practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Reporting: Discourses, Displacement, and Impoverishment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Corporate Social Responsibility from a Discourse Analysis Perspective

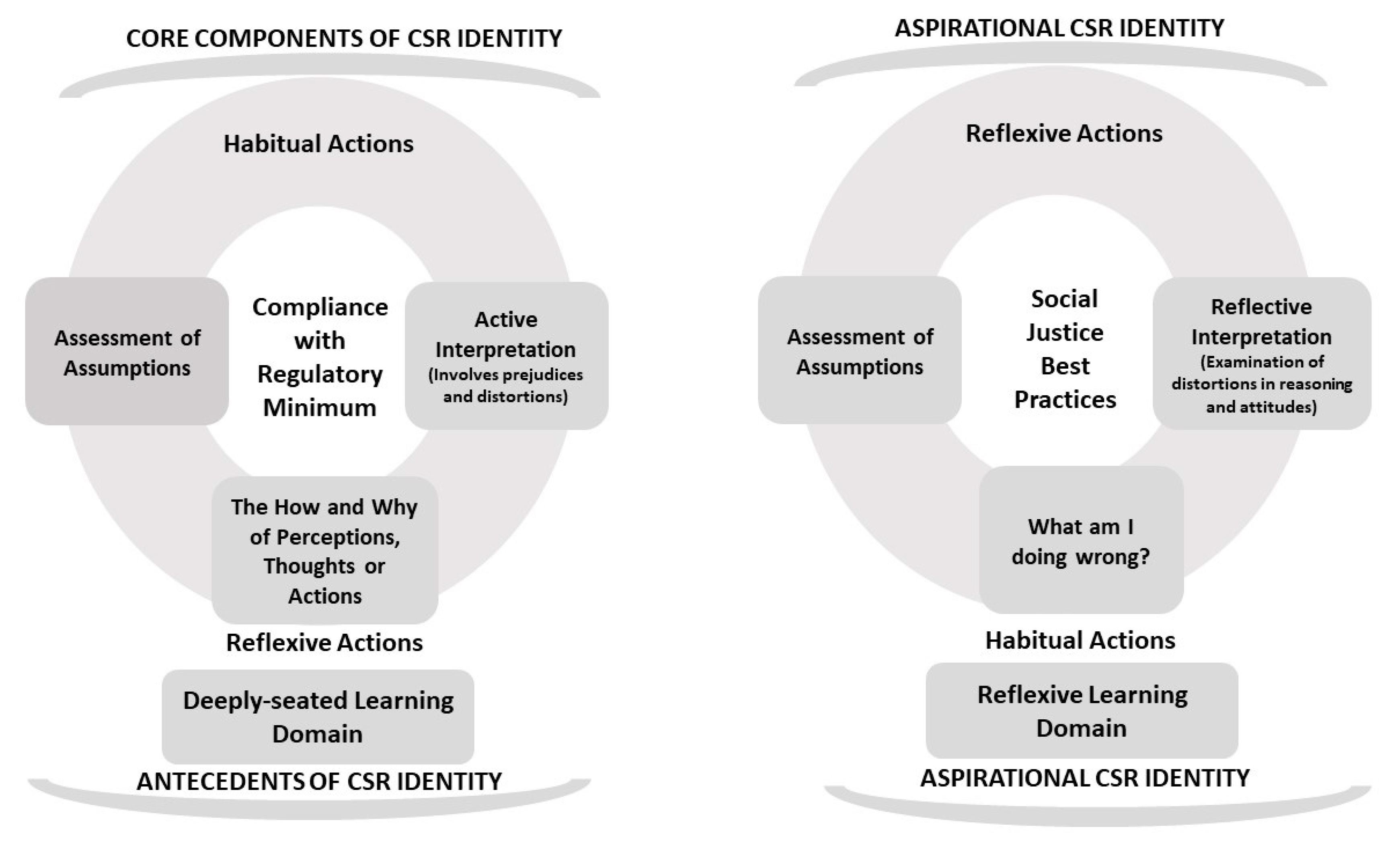

2.1. Developing a Framework to understand CSR-based Identity Perspectives about ESIA

- Antecedents of CSR Corporate Identity: A compliance-based approach to CSR engagements can be reinforced by lifelong learning values;

- Core Components of CSR Corporate Identity: Efforts are constantly geared toward ensuring coherent organisational identities;

- Aspirational Components of CSR Corporate Identity: To gain loyalty, the process of acquiring a license to operate should be altruistic.

2.2. Analysis of Discursive Practices in ESIA

3. Background to the Case Study and Methods

4. The Role of Language in ESIA

4.1. Text Description Phase

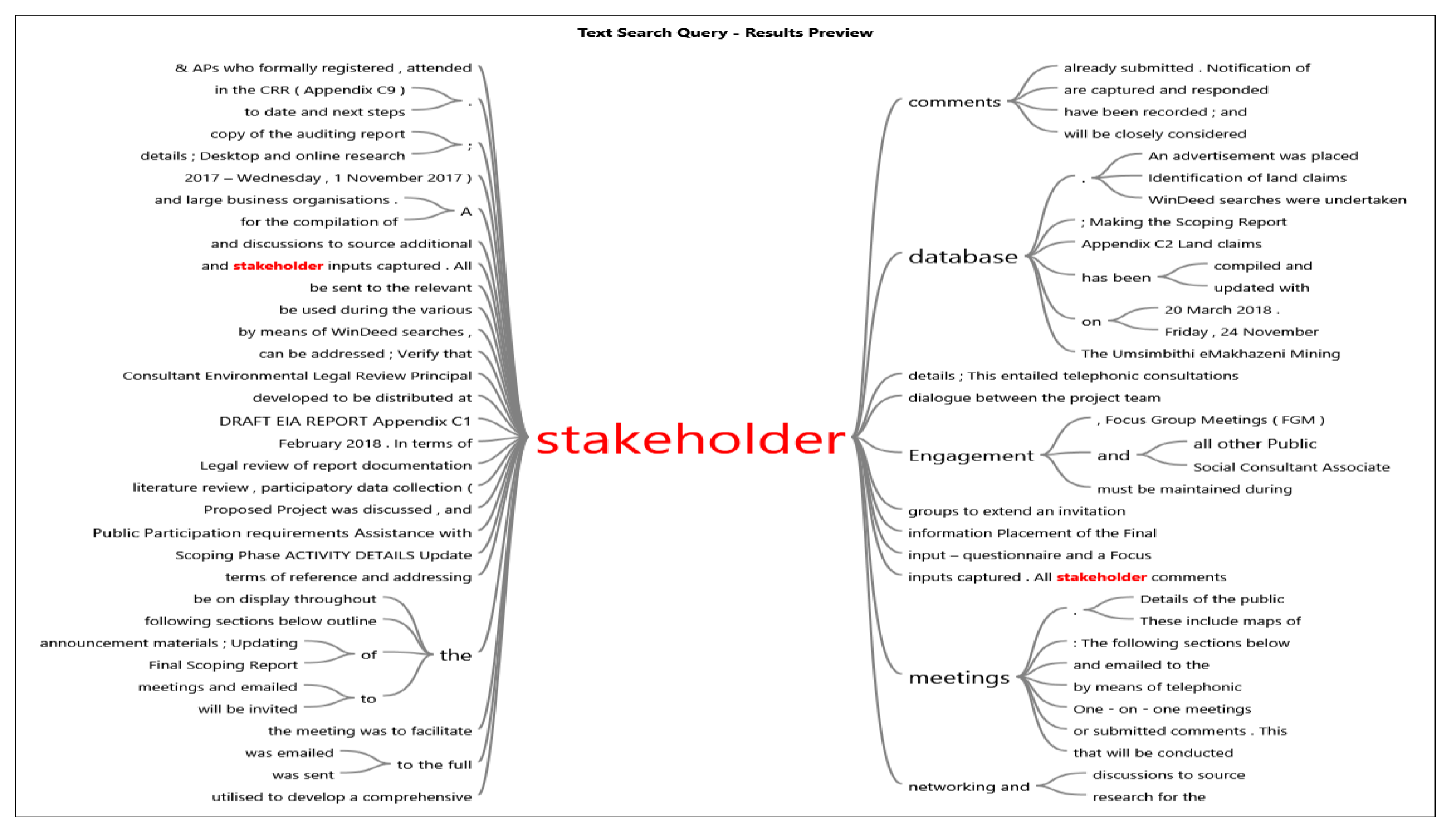

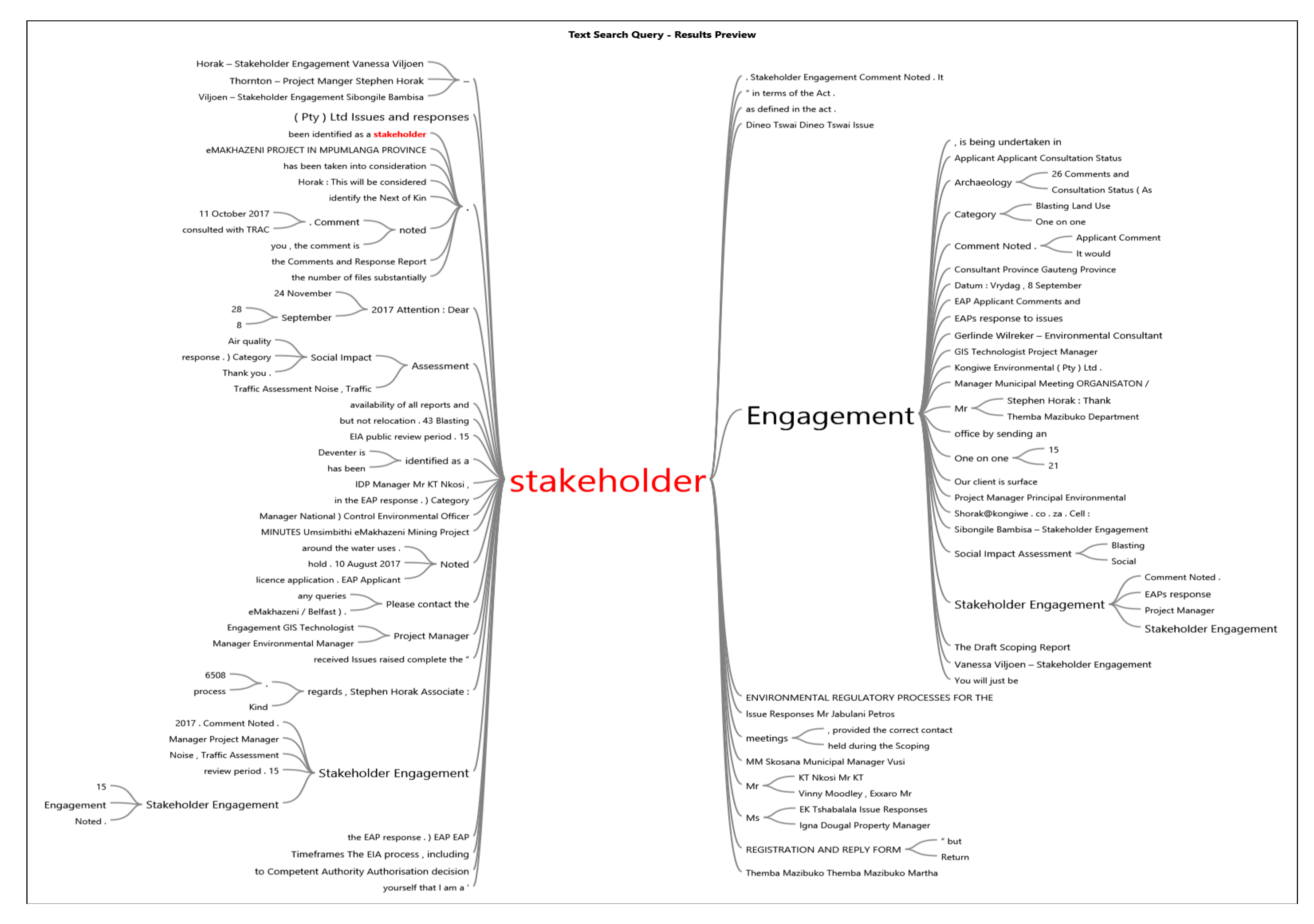

4.1.1. Collocation Analysis

4.1.2. Analysis of Modality

4.2. The Interpretation Phase: Embeddedness of Language in Practice

4.3. The Explanation Phase: Illuminating Processes and Mechanisms in Wider Stakeholder Discourses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Vanclay, F.; Esteves, A.M.; Aucamp, I.; Franks, D.M. Social Impact Assessment: Guidance for Assessing and Managing the Social Impacts of Projects. Available online: http://www.iaia.org/uploads/pdf/SIA_Guidance_Document_IAIA.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Vanclay, F. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serje, M. Social relations: A critical reflection on the notion of social impacts as change. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 65, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alier, J. The environmentalism of the poor. Geoforum 2014, 54, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Conceptualising social impacts. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.; Steyn, M.; Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.M.; Vaz, K. Five ‘big’issues for land access, resettlement and livelihood restoration practice: Findings of an international symposium. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2015, 33, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Diduck, A.P. Reconceptualizing public participation in environmental assessment as EA civics. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 62, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.M.; Sinclair, A.J. Meaningful public participation in environmental assessment: Perspectives from Canadian participants, proponents, and government. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2007, 9, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.; Versteeg, W. A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2005, 7, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, L. Social impact assessment in mining projects in Northern Finland: Comparing practice to theory. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 42, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, L.; Vanclay, F. Challenges in implementing the corporate responsibility to respect human rights in the context of project-induced displacement and resettlement. Resour. Policy 2018, 55, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R. Michel Foucault: Discourse, power/knowledge and deliberative democracy. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Politics; Wodak, R., Forchtner, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, H.L.; Jones, M.D. Making sense of complexity: The Narrative Policy Framework and agenda setting. In Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting; Nikolaos, Z., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F.; Baines, J.T.; Taylor, C.N. Principles for ethical research involving humans: Ethical professional practice in impact assessment Part I. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baines, J.T.; Taylor, C.N.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment and ethical research principles: Ethical professional practice in impact assessment Part II. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Ploeg, L.; Vanclay, F. A human rights based approach to project induced displacement and resettlement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez-Alier, J. The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, S.; Sairinen, R.; Vanclay, F. Using social impact assessment to achieve better outcomes for communities and mining companies. In Mining and Sustainable Development: Current Issues; Lodhia, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, E.; Vanclay, F. The Social Framework for Projects: A conceptual but practical model to assist in assessing, planning and managing the social impacts of projects. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IFC. Handbook for Preparing a Resettlement Action Plan. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/publications/publications_handbook_rap__wci__1319577659424 (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Terminski, B. Development-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: Causes. Consequences, and Socio-Legal Contexts; Ibidem-Verlag: Hannover, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, T.E. Avoiding New Poverty: Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nxesi, T.W. Socio-Economic Impact of Land Restitution in the Ehlanzeni District, Mpumalanga; University of Witwaterstrand: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. A Giant Step in Agriculture Statistics; Statistics South Africa: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2013.

- Von Loeper, W.; Musango, J.; Brent, A.; Drimie, S. Analysing challenges facing smallholder farmers and conservation agriculture in South Africa: A system dynamics approach. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 19, 747–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; ILO. Agricultural Value Chain Development: Threat or Opportunity for Women’s Employment? FAO & IFAD: Rome, Italy; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Du Pisani, J.A.; Sandham, L.A. Assessing the performance of SIA in the EIA context: A case study of South Africa. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2006, 26, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucamp, I.C. Social Impact Assessment as a Tool for Social Development in South Africa: An Exploratory Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ndhlovu, P.T. Corporate social responsibility and corporate social investment in South Africa: The South African Case. J. Afr. Bus. 2011, 12, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlall, S. Corporate social responsibility in post-apartheid South Africa. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F.; Esteves, A.M. Current issues and trends in social impact assessment. In New Directions in Social Impact Assessment: Conceptual and Methodological Advances; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- James, P.; Woodhouse, P. Crisis and differentiation among small-scale sugar cane growers in Nkomazi, South Africa. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2017, 43, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarimo, A. African Land Rights Systems; Langaa RPCIG: Bamenda, Cameroon, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wickeri, E. Land Is Life, Land Is Power: Landlessness, Exclusion, and Deprivation in Nepal. Fordham Int. Law J. 2010, 34, 930. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, J.K. The Political Economy of the Environment; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scharber, H. Book Review: Ecological Economics from the Ground Up; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, P.; Vanclay, F.; Langdon, E.J.; Arts, J. Conceptualizing social protest and the significance of protest actions to large projects. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babarinde, O.A. Bridging the economic divide in the Republic of South Africa: A corporate social responsibility perspective. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2009, 51, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. Pre-Capitalist Socio-Economic Formations: A Collection; Progress Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer, J.M.; Greyser, S.A. Managing the multiple identities of the corporation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 44, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. The emergence of corporate citizenship: Historical development and alternative perspectives. In Handbook of Research on Global Corporate Citizenship; Scherer, A.G., Palazzo, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F.; Hanna, P. Conceptualizing Company Response to Community Protest: Principles to Achieve a Social License to Operate. Land 2019, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IFC. Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/publications/publications_handbook_pps (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Wrench, J.; Punyanunt-Carter, N. An Introduction to Organizational Communication; Creative Commons: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hoops, B.; Saville, J.; Mostert, H. Expropriation and the endurance of public purpose. Eur. Prop. Law J. 2015, 4, 115–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliarino, N. Encroaching on Land and Livelihoods: How National Expropriation Laws Measure Up Against International Standards; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Language and Power, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, S.; Whetten, D.A. Organizational Identity; CT JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ijabadeniyi, A. Exploring Corporate Marketing Optimisation Strategies for the KwaZulu-Natal Manufacturing Sector: A Corporate Social Responsibility Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haji, A.A.; Anifowose, M. The trend of integrated reporting practice in South Africa: Ceremonial or substantive? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 190–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFC. Understanding IFC’s Environmental and Social Due Diligence Process. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/.../IFC+Process.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Jijelava, D.; Vanclay, F. Legitimacy, credibility and trust as the key components of a social licence to operate: An analysis of BP’s projects in Georgia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1569–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartey-Baah, K.; Amponsah-Tawiah, K. Exploring the limits of Western corporate social responsibility theories in Africa. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W. Revisiting Carroll’s CSR pyramid: An African perspective. In Corporate Citizenship in Developing Countries; Pedersen, E.R., Huniche, M., Eds.; Copenhagen Business School Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006; pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ijabadeniyi, O.A.; Ijabadeniyi, A. Governance of Nanoagriculture and Nanofoods. In Nanoscience and Nanotechnology: Advances and Developments in Nano-Sized Materials; Van de Voorde, M., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- West, D. Strategic Marketing: Creating Competitive Advantage, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, N. Corporate social responsibility and compliance: Transnational mining corporations in Tanzania. Macquarie J. Int. Comp. Enviorn. Law 2013, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler, I. Four Pragmatists: A Critical Introduction to Peirce, James, Mead, and Dewey; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery, A.; Baker, P. Corpora and Discourse Studies: Integrating Discourse and Corpora; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tienari, J.; Vaara, E.; Björkman, I. Global capitalism meets national spirit: Discourses in media texts on a cross-border acquisition. J. Manag. Inq. 2003, 12, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleming, A.; Vanclay, F.; Hiller, C.; Wilson, S. Challenging dominant discourses of climate change. Clim. Chang. 2014, 127, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porpora, D.V. Reconstructing Sociology: The Critical Realist Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Archeologie Vědění; Herrmann & Synové: Prague, Czech Republic, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. What is Enlightenment? In What Is Enlightenment? Eighteenth-Century Answers and Twentieth-Century Questions; Schmidt, J., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 382–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Language and Power; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Language and Power, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fuls, F. Involuntary Relocations: Glencore’s Umsimbithi Mine. Available online: https://www.pambazuka.org/governance/involuntary-relocations-glencore%E2%80%99s-umsimbithi-mine (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- The Presidency. Statement from President Jacob Zuma on the Marikana Lonmin Mine Workers Tragedy, Rustenburg. Available online: http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/speeches/statement-president-jacob-zuma-marikana-lonmin-mine-workers-tragedy%2C-rustenburg?page=12#!slider (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Mining Charter. Broad-Based Socio-Economic Empowerment Charter for Mining and Minerals Industry; Government Gazette No. 41934; Department of Mineral Resources: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018.

- The South African. Marikana: What Was Cyril Ramaphosa’s Role? Available online: https://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/marikana-what-did-cyril-ramaphosa-do/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- The Conversation. Marikana: It’s Time Ramaphosa Moved on Accountability and Reparations. Available online: https://theconversation.com/marikana-its-time-ramaphosa-moved-on-accountability-and-reparations-101479 (accessed on 17 April 2019).

- Villa, S. Coal giant’s operations not a blast for locals. Available online: https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/lifestyle/2014-03-02-coal-giants-operations-not-a-blast-for-locals/ (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Hume, N.S.D.; Sanderson, H. Glencore: An Audacious Business Model in the Dock. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/c9e674b0-8105-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d (accessed on 17 August 2019).

- Onstad, E.; MacInnis, L.; Webb, Q. Special Report: The biggest Company You Never Heard of (Glencore). Available online: https://climateerinvest.blogspot.com/2011/02/special-report-biggest-company-you.html (accessed on 17 August 2019).

- Gubrium, J.F.; Holstein, J.A.; Marvasti, A.B.; McKinney, K.D. The Sage Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jäger, S.; Maier, F. Theoretical and methodological aspects of Foucauldian critical discourse analysis and dispositive analysis. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis; Wodak, R., Meyer, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, M.; Fiore, Q. The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J. Corpus, Concordance, Collocation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, J.L. Intertextuality and educational research. Linguist. Educ. 1992, 4, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Discourse and text: Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. Discourse Soc. 1992, 3, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, D.; Mayr, A. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, P. Marikana, turning point in South African history. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2013, 40, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, D.W. African Ubuntu Philosophy and Global Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangaliso, M.P. Building competitive advantage from ubuntu: Management lessons from South Africa. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2001, 15, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I. Corporate Strategy: An Analytic Approach to Business Policy for Growth and Expansion; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, W. The State We’re In; Vintage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelson, P. The Blair Revolution: Can New Labour Deliver? Faber & Faber: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, T. Tony Blair Outlines to a Singapore Business Forum His Vision of a Revitalised British Economy: A Stake in the Future. Available online: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12054287.Tony_Blair_outlines_to_a_Singapore_business_forum_his_vision_of_a_revitalised_British_economy_A_stake_in_the_future/ (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Groundwork. Groundwork’s Submissions on the Proposed Umsimbithi Emakhazeni Mining Project. Available online: https://www.groundwork.org.za (accessed on 23 November 2019).

- Nussbaum, B. African culture and Ubuntu. Perspectives 2003, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dare, M.; Schirmer, J.; Vanclay, F. Community engagement and social licence to operate. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2014, 32, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

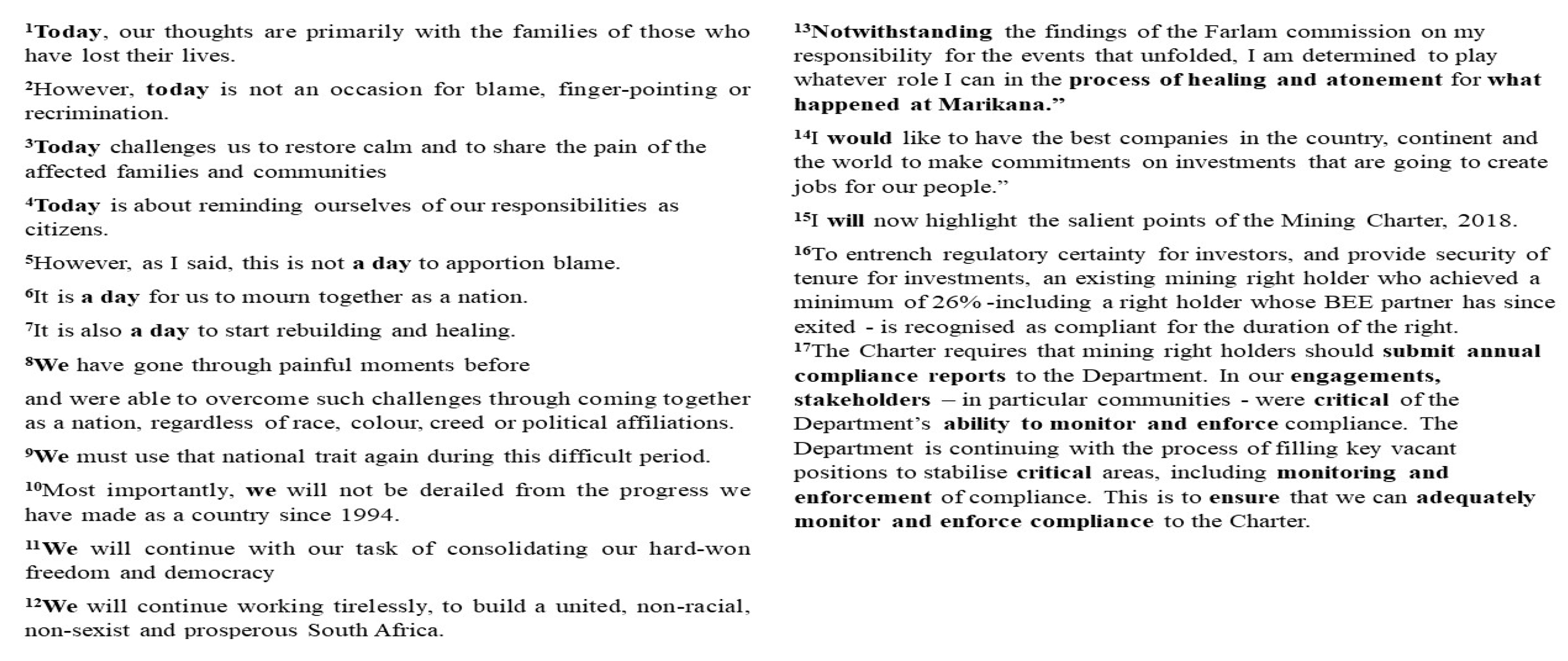

| Evidence from Textual Data | Espoused Values | Ideological Underpinning |

|---|---|---|

| PPL1 (1–12) | Resistance to hardship | Ubuntu |

| PPL2 (13–14) | Endurance | Economic prosperity for the ‘atonement of blood’ |

| Mining Charter (15–17) | Tolerance | Affirmative action |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ijabadeniyi, A.; Vanclay, F. Socially-Tolerated Practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Reporting: Discourses, Displacement, and Impoverishment. Land 2020, 9, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9020033

Ijabadeniyi A, Vanclay F. Socially-Tolerated Practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Reporting: Discourses, Displacement, and Impoverishment. Land. 2020; 9(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9020033

Chicago/Turabian StyleIjabadeniyi, Abosede, and Frank Vanclay. 2020. "Socially-Tolerated Practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Reporting: Discourses, Displacement, and Impoverishment" Land 9, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9020033

APA StyleIjabadeniyi, A., & Vanclay, F. (2020). Socially-Tolerated Practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Reporting: Discourses, Displacement, and Impoverishment. Land, 9(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9020033