Resilience of Traditional Livelihood Approaches Despite Forest Grabbing: Ogiek to the West of Mau Forest, Uasin Gishu County

Abstract

1. Background

2. Pre-Colonial Land Arrangement between Ogiek (Ndorobos) and other Communities

3. Debates on Ogiek’s Right to Ancestral Land

3.1. Why Examine Conflict in Relation to Settlement Schemes and Landownership in Rift Valley?

3.2. Salient Debates

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Theoretical Framework

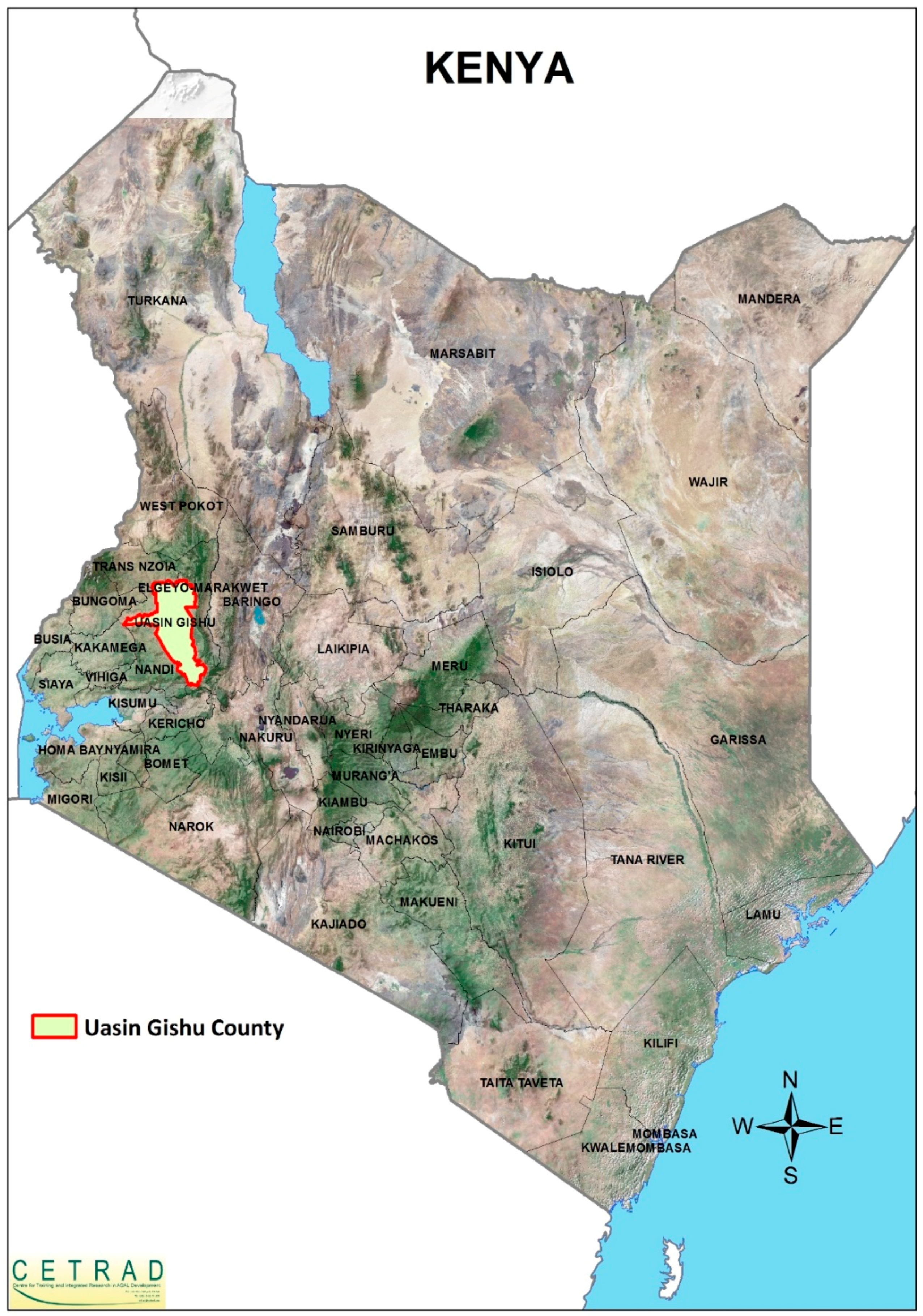

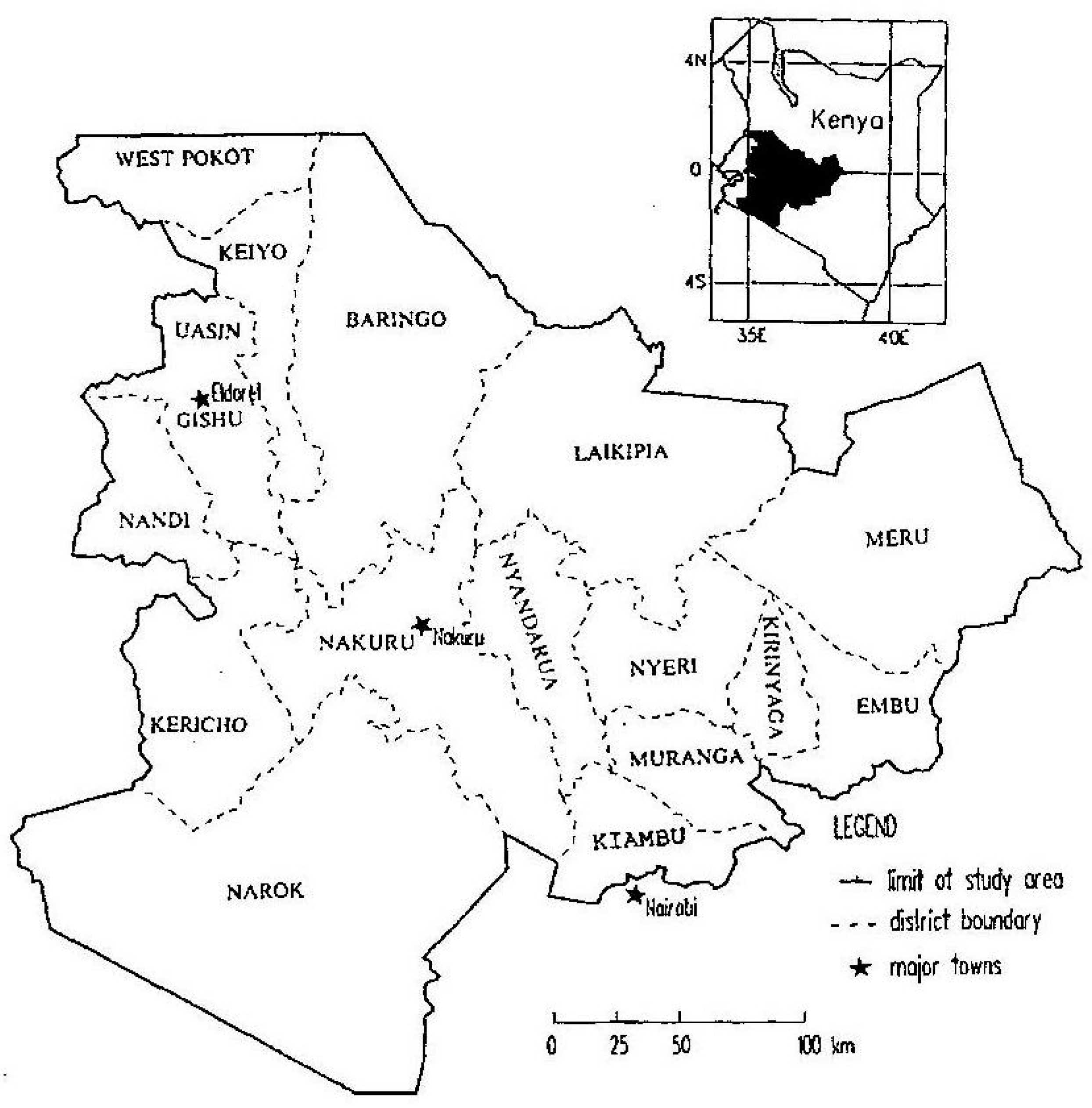

4.2. Local and Topographic Characteristics of Uasin Gishu

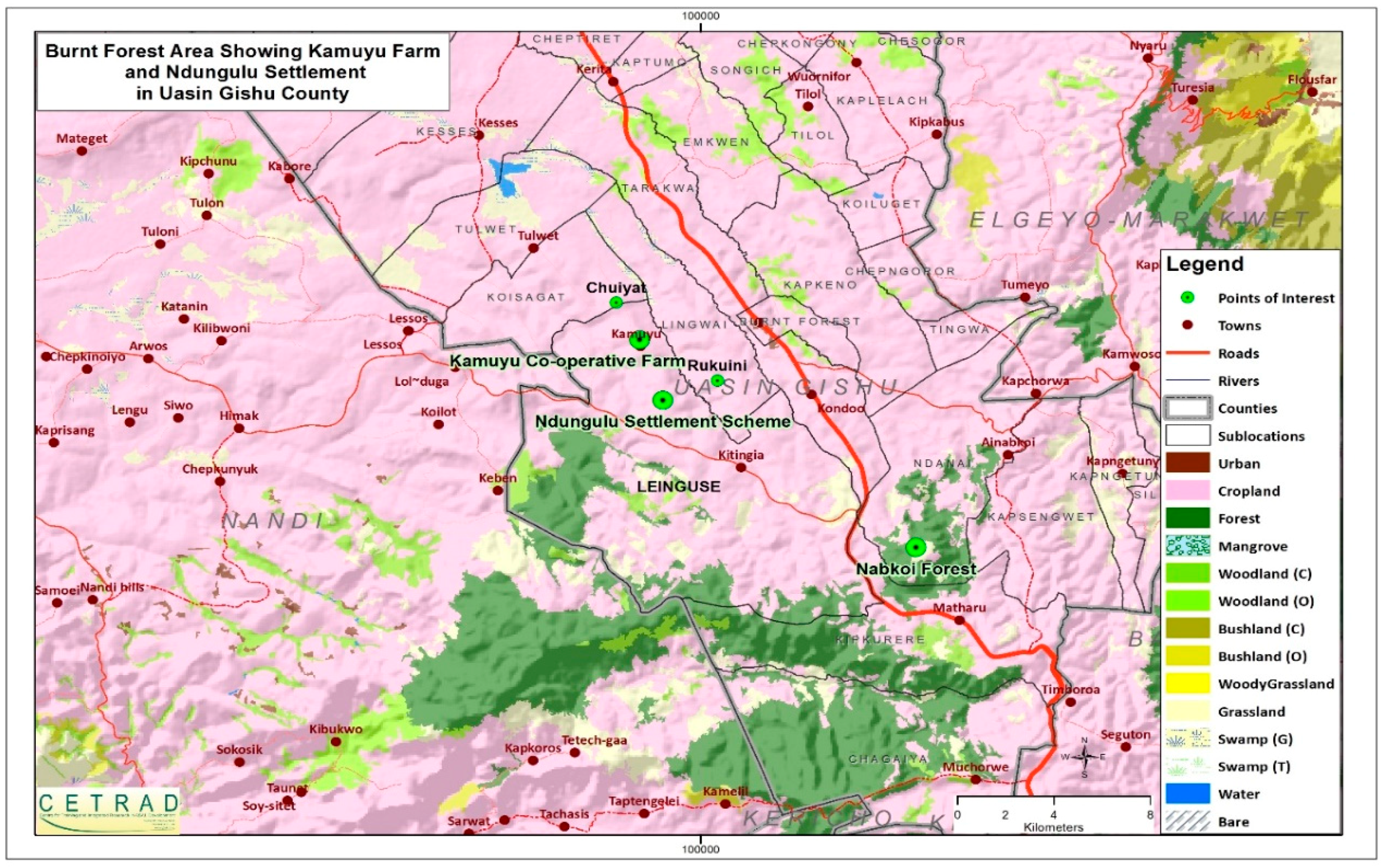

4.3. Description of Study Area: Ndungulu

4.4. Description of Study Area-Kamuyu

As an elder shareholder described … “At the dawn of independence in 1965, a group of 233 Kikuyus and 7 Kalenjin from the Nandi sub group bought the Kamuyu land that was about 6000 acres. However, after the land clashes of 1992, the 7 Kalenjin were forced to leave and their land bought from them. The 1965 land deal was a tripartite agreement brokered between the lending Bank, the co-operative and DC MacLeod, a white British colonial settler. The Kikuyu buyers nicknamed him “gichaga” because he used to quarrel with everybody. Some called him ‘Kiguru’ because he walked with a limp. The farm was sold at 1,000 Kenya shillings per share including the farm equipment. At the time, Kamuyu was formed, the Kikuyu were rearing pigs, poultry and cows as common investment. All members were entitled to a maximum of 3 acres for personal use. The rest was used communally and the proceeds re-invested through their co-operative committee to offset the bank loan that was used to purchase the land.” Interview with a 75-year-old male shareholder of the Kamuyu Cooperative society.

“After purchasing the farm from the white owner in 1965, the members of Kamuyu Co-operative farm decided to demarcate the land in 1980’s after the bank loan was settled. That marked the end of community activities such as planting maize and pyrethrum. Before demarcation every member had a share of 3 acre each and the rest was for the society, afterwards, every member was entitled to at least 7 acres. The good fertile areas were referred to as the ‘special’. Those who obtained the sloppy areas were given 8 acres each, those who obtained the sloppy and rocky areas were given 9 acres each while those who obtained the sloppy, hilly and rocky areas which were had to plough were given 10 acres”. Excerpt from key informant interview, Kamuyu Cooperative society.

4.5. Study Design, Data Collection and Analysis

4.6. Study Limitation

5. Findings and Discussions

5.1. Devolution, Land Reforms and the role of the National Land Commission (NLC)

5.2. The Role of the Assistant Chief’s Office in Adjudicating and Arbitrating over “Distress” Land Sales

5.3. Contestation of Maintaining Traditional Versus Modern Livelihoods (Ogiek, Chief’s Office and NGOs)

5.4. Contestation of Access and Use of Mau Forest (between Ogiek and Kenya Forest Service)

“We have some “shamba farmers” on Ndungulu farm who had been allowed to cultivate on half acre each in the Sereng’onik section of Mau forest. This is actually a community forest association (CFA), called Leinguse peace and conflict management group. It has 72 members from Ogiek, Kikuyu and Kalenjin communities who are both female and male. What stood out for me was that out of the 72 members, only 11 are Ogiek. The Ogiek have no money to afford to pay for membership in such associations. The Ogiek are not interested in the charcoal business like the Kalenjin and Kikuyu. The dorobo (Ogiek) are not interested because they like to brew alcohol and are lazy. In fact, the Ogiek who are registered do so because it is the only means through which the Kenya Forest Service allows them to harvest honey using their traditional beehives. The forest is also important for carrying out circumcision ceremonies.” Interview with Chairperson, Leinguse peace and conflict management group.

5.5. Resolving Land Issues in an Enabling Political Environment: The Kikuyu Approach

Case of Legal Intervention by Hon. Martha Karua, Former Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs

“Mostly the Kamuyu cooperative committee resolves the cases we especially land disputes cases. However, big cases are handled by our Kikuyu politicians. For example, during the time we were doing demarcation a government surveyor was employed to do the demarcation, previously it was done by a private surveyor and that was back in 1980. The government surveyor was brought to come and put clear boundaries for issuance of title deeds. The surveyor was not good in his work and he cut out some portions from an owner and allocated them to another person. People started complaining and they started so many cases of that improper land allocation. When I became chairman in 2004, the demarcation issue was the first case I started handling. We were happy because Mwai Kibaki (Kikuyu ethnicity) was president and things were better for Kikuyus. Some of the committee members and I went to Nairobi and met Martha Karua (the then Minister of Justice and constitutional affairs) who assigned us a lawyer to oversee that case. Before the case could pick up came the 2007 post-election violence. When this confusion ended I went back to her office but she was transferred from that ministry to another. She is a good Kikuyu politician, because she still resolved our matter even though she had moved.”(KII, Chairman, Kamuyu Cooperative Farm)

6. Discussions

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kariuki, S. Can a botched land reform programme explain Kenya’s political crisis? J. Afr. Elect. 2008, 7, 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ogot, B.A.; Ochieng, W.R. Decolonisation and Independence in Kenya 1940–93; James Currey: London, UK, 1995; p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- Okoth-Ogendo, H.W.O. Property systems and social organisation in Africa: An essay on the relative position of women under indigenous and received law. In The Individual under African Law: Proceedings of the First all-Africa Law Conference October 11–16, 1981; Takirambudde, P.N., Ed.; Royal Swazi Spa: Lobamba, Swaziland, 1982; pp. 47–55, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Syagga, P. Public Land, Historical Land Injustices and the New Constitution; Constitution Working Paper No. 9; Society for International Development, Regal Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, B.; Lonsdale, J. Unhappy Valley: Conflict in Kenya and Africa Book One: State and Class; James Currey: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrenson, M.P.K. Land Reform in the Kikuyu Country: A Study in Government Policy; Oxford University Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Harbeson, J.W. Land and the Quest for a Democratic State in Kenya: Bringing Citizens back in. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2012, 55, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C. Land conflict and distributive politics in Kenya. Afr. Stud. Rev. J. Afr. Stud. Assoc. 2012, 55, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C. Property and Political Order in Africa: Land Rights and the Structure of Politics; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ntsebeza, L.; Hall, R. The Land Question in South Africa: The Challenge of Transformation and Redistribution; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, J.-G.; Probst, P.; Schmidt, H. African Modernities: Entangled Meanings in Current Debate; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yeoman, G. High altitude forest conservation in relation to the Dorobo people. Kenya Past Present. 1993, 25, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, T. The Understanding of Institutions and Their Link to Resource Management from a New Institutionalism Perspective; Working Paper 1 NCCR North-South; University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kipkorir, B.E. People of Rift Valley; Evans Brothers: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, G. “I Say to You”: Ethnic Politics and Kalenjin of Kenya; University of Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, R. The Ogiek History Kenya before 1900. Master’s Thesis, East African Publishing House Limited, Nairobi, Kenya, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, S. Ethnicity, violence, and the immigrant-guest metaphor in Kenya. Afr. Aff. 2012, 111, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, G. Mau Mau from Below; James Currey: London, UK; East Africa Educational Publishers: Nairobi, Kenya; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kimaiyo, T.J. Ogiek Land Cases and Historical Injustices, 1902–2004; Ogiek Welfare Council: Nakuru, Kenya, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, J. Supporting the Right of a Kenyan Indigenous Group; Ogiek Welfare Council Publishers: Nakuru, Kenya, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alden Wily, L. Risks to the sanctity of community lands in Kenya. A critical assessment of new legislation with reference to forestlands. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, D. Being Maasai, Becoming Indigenous. In Postcolonial Politics in a Neoliberal World; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Médard, C. Quelques clés pour démêler la crise kenyane: Spoliation, autochtonie et privatisation foncière. IFRA—Sables-d’olonne n.a. Cah. D’Afrique De L’Est 2008, 37, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kitching, G. Class and Economic Change in Kenya: The Making of an African Petit Bourgeoisie 1905–1970; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Haugerud, A. The Culture of Politics in Modern Kenya; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chauveau, J.P.; Cisse, S.; Colin, J.P.; Cotula, L.; Delville, P.L.; Neves, B.; Quan, J.; Toulmin, C. Changes in Customary Land Tenure Systems in Africa; Russel Press: Nottingham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leakey, L.S.B. Mau Mau and the Kikuyu; Routledge Publishers: Oxon, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, R.D. Acceptees and Aliens: Kikuyu settlement in Masaailand. In Being Masaai: Ethnicity and Identity in East Africa; Spear, T., Waller, R.D., Eds.; James Currey Publishers: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Joireman, S.F. Entrapment of Freedom: Enforcing Customary Property Rights Regimes in Common-law Africa. In The Future of African Customary Law; Fenrich, J., Galizzi, P., Higgins, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Chanock, M. Law, Custom and Order. In The Colonial Experience in Malawi and Zambia; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, R. Ethnicity without Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten, M.M.E.; Owuor, S.O. Weapons of mass destruction: Land, ethnicity and the 2007 elections in Kenya. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 2009, 27, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagwanja, K. Courting genocide: Populism, ethno-nationalism and the informalisation of violence in Kenya’s 2008 post-election crisis. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 2009, 27, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeves, J.S. Democracy unravelled in Kenya: Multi-party competition and ethnic targeting. Afr. Identities 2011, 9, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopp, J. Can Moral Ethnicity Trump Political Tribalism? The Struggle for Land and Nation in Kenya. Afr. Stud. 2002, 61, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.M.; Freudenthal, E.; Kenrick, J.; Mylne, A. The whakatane mechanism: Promoting justice in protected areas. Nomadic Peoples 2012, 16, 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E. Ownership and Political Ecology. Anthr. Q. 1972, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P. The Political Economy of Soil Erosion in Developing Countries; Longman: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz, L. Political Ecology and Environmental Management in the Loess Plateau, China. Hum. Ecol. 1993, 21, 327–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.H.; Wali, A. Indigenous land tenure and tropical forest management in Latin America. Ambio 1994, 23, 485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Speranza, C.I.; Kiteme, B.; Ambenje, P.; Wiesmann, U.; Makali, S. Indigenous knowledge related to climate variability and change: Insights from droughts in semi-arid areas of former Makueni District, Kenya. Clim. Chang. 2010, 100, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, T.; Galvin, M. Conclusion: Participation, Ideologies and Strategies: A Comparative new Institutionalist Analysis of Community Conservation. In People, Protected Areas and Global Change; Galvin, M., Haller, T., Eds.; Geographica Bernensia: Bern, Switzerland, 2008; Volume 3, pp. 507–549. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, D.; Cheeseman, N.; Gardner, L. Our turn to eat: Politics in Kenya since 1950; Lit Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wachira, M.G. Vindicating Indigenous Peoples Land Rights in Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger, J. Anthropology and the New Institutionalism. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. 1998, 154, 1–2, 774–789. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger, J. Making a Market; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- NEMA. National Environmental Management Report, NEMA 2009–2013; Ministry of Land and Mineral Resources: Uasin Gishu County, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The Kenya National Population Census; Kenya Bureau of Statistics: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009.

- Nicholson, M.J.L. Soils and Land Use on the Northern Foothills of the Aberdare Range Kenya. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Maloba, O.W. Mau Mau and Kenya: An Analysis of a Peasant Revolt; James Currey: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, C.; Dyzenhaus, A.; Gargule, A.; Gateri, C.; Klopp, J.; Manji, A.; Ouma, S.; Owino, J.K. Land Politics under Kenya’s New Constitution: Counties, Devolution, and the National Land Commission; Working Paper Series 2016; School of Economics: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pala, A.O. Women’s Access to land and their role in agriculture and decision-making on the farm: Experiences of the Joluo of Kenya: Experiences of the Joluo of Kenya, Nairobi. J. East. Afr. Res. Dev. 1983, 13, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Affou, S.; Crook, R.; Hammond, D.; Vanga, A.F.; Yeboah-Owusu, M. The Law, Legal Institutions and Protection of Land Rights in Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire: Developing a more Effective and Equitable System; Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rangan, H.; Gilmartin, M. Gender Traditional Authority and Politics of Rural Reform in South Africa. Dev. Chang. 2002, 33, 633–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbote-Kameri, P.; Nyamu-Musembi, C. Mobility, Marginality and Tenure Transformation in Kenya. Explorations of Community Property rights in Law and Practice. Nomadic Peoples 2013, 17, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne Delville, P. When farmers use “pieces of paper” to Record their land transactions in Francophone rural Africa: Insights into the Dynamics of Institutional Innovation’. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2002, 14, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkondo, M. Indigenous African Knowledge Systems in A Polyepistemic World: The Capabilities Approach and The Translatability of Knowledge Systems. In The Southern African Regional Colloquium on Indigenous African Knowledge Systems: Methodologies and Epistemologies for Research, Teaching, Learning and Community Engagement In Higher Education; University Of Kwazulu-Natal 23 November 2012; Howard College: Big Spring, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Semali, L.M.; Kincheloe, J.L. Introduction: What is Indigenous Knowledge and Why Should We Study It? In What Is Indigenous Knowledge? Voices from the Academyi; Semali, L.M., Kincheloe, J.L., Eds.; Falmer Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Koech, K.C.; Ongugo, O.P.J.O.; Mbuvi, T.E.M. Community Forest Associations in Kenya: Challenges and Opportunities; Kenya Forestry Research Institute: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Oduol, P.A. The Shamba system: An indigenous system of food production from forest areas of Kenya. In Meterology and Agroforestry, Proceeding of the Application of Meteorology to Agroforestry Systyems Planning and Management, Nairobi, Kenya, 9–13 February 1987; Riefsnyder, W.S., Darnhofer, T.S., Eds.; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 1989; pp. 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Witcomb, M.; Dorward, P. An assessment of the benefits and limitations of the shamba agroforestry system in Kenya and of management and policy requirements for its successful and sustainable reintroduction. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 75, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stapele, N. Mediations of Violence in Africa: Fashioning New Futures from contested pasts. In Masculinity, Ethnicity and Violence in Nairobi; Kapteijns, L., Richters, A., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mathu, W.; Ng’ethe, R. Forest Plantation and Woodlots in Kenya. Afr. For. Forum Work. Pap. 2011, 1, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Wandahwa, P.; Van Ranst, E. Qualitative land suitability assessment for pyrethrum cultivation in west Kenya based upon computer-captured expert knowledge and GIS. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1996, 56, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyinga, K.; Mkize-Binswanger, H.; Bourguignon, C.; Van den Brink, R. Agricultural Land Redistribution: Towards Greater Consensus; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 87–117. [Google Scholar]

- Furedi, F. The Mau Mau War in Perspective; James Currey: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lesorogol, C.K. Contesting the Commons: Privatizing Pastoral Lands in Kenya; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For example, in Kenya there has been reform in land laws rather than policies to encourage social transformation ideologies on equality and equity. Taking land ownership for example, the Constitution of 2010, National Land Policy of 2009 and Land Act 2012, Land Registration Act of 2012 all promote land ownership anchored on formal title as the defining feature of property relations. However, this co-exists with and is constantly in tension with broader and dynamic social processes and institutions that shape property relations by constantly balancing between various competing claims and values, rights and obligations. The Community Land Act 2016 takes these factors into account. |

| 2 | In this study, I categorize Kalenjin as ‘pastoralists’ because pre-historically, they were pastoralists [14]. In addition, prominent Kalenjin leaders such as Deputy President William Ruto, addresses his Kalenjin community as “pastoralists” in public functions, to show the importance that the community places on livestock keeping. Notably, over the years, the Kalenjin have gradually interacted with Bantu speaking communities and have adapted arable farming and livestock keeping [15]. |

| 3 | I also use the term “immigrant guests” because during the 2007 post-election violence, it was used to refer to Kikuyu who have migrated into the Rift Valley, see Jenkins, 2012 [17]. |

| 4 | In Part IV (No.31), the new Forest Conservation and Management Act simply states that “all public forests in Kenya are vested in the service.”. This leaves a loophole in the rights of those communities that consider forestland as ancestral land. Alden Wily (2018, p. 667) [21] argues that “complainant communities understandably consider the privatization of forest reserves as removing their forested community lands yet further from their grasp”. |

| 5 | The Kenya Forest Service is a semi-autonomous agency set up in 2007 to conserve, develop and sustainably manage forest resources for the country’s socio-economic development. It is managed by a board of directors drawn from both the private and public sectors that has the mandate to oversee the development of the entire forest sector. The Kenya Forest Service also regulates the harvesting of firewood by issuing licenses to any persons interested in the wood fuel from the forest. |

| 6 | Haugerud [25] has argued that in Central province of Kenya in the nineteenth century was made up of people with a long history of relations through trade, migration, marriage, clientage and adoption. Neither commercialization nor wealth was unknown in Central Kenya during the nineteenth century. |

| 7 | Chauveau, et al. [26] p. 14 defines the term tutorat as “the reciprocal social relations that develop when a stranger (or group of strangers) and his family are received into a local community for an indeterminate period, which may span generations. Transfers are effected through the transfer of land rights between a customary land owner ‘tuteur’ who is either a native or autochthone. The institution of Tutorat was embedded in client patron-relationships and socio-political relationships”. |

| 8 | See Leakey (1952, p. 4) [27]. |

| 9 | A type of collective tutorat at the village level (i) where the bilateral relations between tuteurs and strangers are entirely mediated by the social and political organization of the local society. A type of collective inter-village tutorat (ii) where the customary rules that determine relations with communities settled on the lands of an older village are same as those that define the relationships between a newcomer and his tuteur at village level. A type of individualized tutorat (iii) where the bilateral relationship between tuteur and stranger is very strong and seems relatively autonomous of the social and political organization of the local society. (Chauveau et al., 2006, p. 16) [26]. |

| 10 | Report of the Prime Minister’s Taskforce on the Conservation of the Mau Forest complex. http://www.kws.go.ke/content/mau-forest-restoration-publications. |

| 11 | Speranza et al. (2009) correlates the usefulness of African indigenous knowledge systems and modern science for enhancing food security and climate change adaptation in Kenya [41]. |

| 12 | Land grabbing is seen as part of the wider, large-scale land acquisition schemes to be embraced by African governments. |

| 13 | Médard (2008, pp.81–98) argues that the Ogiek of Mount Elgon or from Mau forest areas claim to be the autochthons of Rift Valley and are reclaiming forest land because of the potential benefits of owning highly fertile land in Rift Valley and not necessarily to revert back to their hunter-gatherer customary land administration system [23]. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | The detailed information on the “indigenousness” of the Ogiek can be found on various websites such as the http://www.ogiekpeoples.org/. |

| 16 | There are other constituencies namely Ainabkoi, Kapseret, Moiben, Turbo and Soy. There are three local authorities namely Wareng County Council, covering the widest area with 21 wards, Eldoret Municipal council with 15 wards and Burnt Forest Town Council with 6 wards. |

| 17 | Statistics from the NEMA report were published before the establishment of county system of local governance. Uasin Gishu district is now called Uasin Gishu County. |

| 18 | According to the Kenya National Population Censu, 2009 [49], p. 145, the area of Ol’leinguse is 132 square kilometers, with a population density of 122. A total of 7983 are male, while 8122 are female. There are 3177 households in the Ol’leinguse location. |

| 19 | This report was published before the establishment of county system of local governance [47]. The former Uasin Gishu district and its environs is now referred to as Uasin Gishu County. |

| 20 | Ol’leinguse is a Maasai name. |

| 21 | Uasin Gishu is a Maasai name. The area was inhabited by Maasai before the colonial period. |

| 22 | The 2009 Report of the Prime Minister’s Taskforce on the Conservation of the Mau Forest complex gives a figure of 788.3 hectares as the land given to Ogiek, while NEMA report gives it as 740 hectares. |

| 23 | According to the Complainants’ Submissions on the Merits, Court Document submitted to the African Court on Human Rights and Peoples Rights. It states that the Ogiek from Kipkurere were evicted in 1986 and forced to live in a small village Ngatipkong. This was part of the evidence used by the Ogiek “complainants” in court proceedings for the African Commission on Human Rights and Peoples Rights Vs Republic of Kenya. Communication No. 006/2012. Which helped them win the case on 26 May 2017. http://minorityrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Final-MRG-merits-submissions-pdf.pdf |

| 24 | Rich and educated Kikuyu men were recruited as surveyors and clerks, giving them some leverage in the land consolidation program. For instance, collaborators tended to favor people who had supported the government while discriminating against Mau Mau fighters and their sympathizers when allocating land. [6], p. 242. |

| 25 | Yin (2003, pp. 10–11) states that the second limitation with case studies is that they provide little basis for scientific generalization. A question often posed is “How can you generalize from a single case?” However, Yin states that, as with experiments and surveys, case studies are generalizable to theoretical propositions and not to populations or universes [48]. |

| 26 | The third limitation of case studies, according to Yin, is that they take too long and result in massive unreadable documents. This is because of ethnographic and participant observation methods involved. However, this all depends on the timeframe of the investigator and the aims and objectives of the study [48], pp. 10–11. |

| 27 | Land Control Boards are now been abolished since the establishment of the National Land Commission (NLC) in 2012. However, the NLC will set up new land boards committees at local level that preside over all land matters, that will include the one-third representation by women as required by the new constitution. |

| 28 | |

| 29 | In most communities in Kenya, land adjudicators and arbitrators were men. This pattern was mirrored in the structure of land committee and board members. The justification used for a formal institution was simple-women’s participation in this process has been almost non-existent in the past. ‘Customary law’ was used as the reference point [53], p. 39. |

| 30 | When the researcher began data collection in 2012, the Kesses Land Board which had jurisdiction over the Ol’leinguse location where the case studies are situated, was all male. The members stated that is was “gender compliant” because the secretary Ms Rael Lamai, was always present at meetings to take notes and to kindly serve them with tea. |

| 31 | This was an improvement of the Trust land Act, which was more attune to the governance of ranches by pastoralists. The CLA is envisaged as a big win for communities which value the communal land tenure systems. In the CLA, “Community” has been defined to mean a consciously distinct and organized group of users of community land who are citizens of Kenya and share any of the following attributes: common ancestry, similar culture or unique mode of livelihood; socioeconomic or other similar common interest; geographical space; ecological space; or ethnicity. The constitution of a community is therefore not limited to ethnic lines as is the case with the current practice. The reason for this new clause being that ancestral land claims would balkanize the country into ethnic enclaves. |

| 32 | The term “customary land rights” is defined to mean rights conferred by or derived from African customary law, customs or practices provided that such rights are not inconsistent with the Constitution or any written law. |

| 33 | Contrary to the arguments made by [9], pp. 64–68, on “neo-customary” land regimes in Africa, the context is different for Ol’ leinguse location. Unlike other countries such as Ghana (Affou et al., 2007) [54], and South Africa (Rangan and Gilmartin 2002) [55], whose ethnic groups have well defined structures of chieftaincies, the ethnic groups in the area of Uasin Gishu did not have chiefs as land administrators. This position was adopted from the colonial period, by the post-colonial government. |

| 34 | At the time of the interview in 2012, the Assistant Chief, a Kalenjin, had held this position since 1989 and was relied upon as the “institutional memory” for the land sales. |

| 35 | Sub ethnic community of Nandi are from Nandi county, the Kipsigis are from Kericho county, Tugen are from Baringo county and Keiyo from Elgeyo Marakwet counties. |

| 36 | Mercy corps has many projects in Uasin gishu on peace. There are passionfruit for peace in Olare that is in the north, then goats for peace in Kesses, then in Cheptiret there is a rehabilitated market for peace, a poultry project in Chegeiya and a bridge project in Matharu. |

| 37 | Information derived from a key informant interview in 2012, with a Peace Monitor at the Ministry of Internal affairs, District Commissioners office, Uasin Gishu county, Eldoret town. |

| 38 | |

| 39 | The Star interview: We’ve restored 850k hectares of degraded forests by involving communities-PS. https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2017/06/22/interview-weve-restored-850k-hectares-of-degraded-forests-by-involving_c1579273. |

| 40 | Picture taken by Jemaiyo Chabeda. |

| 41 | |

| 42 | |

| 43 | According to the Complainants’ Submissions on the Merits, Court Document submitted to the African Court on Human Rights and Peoples Rights. This was part of the evidence used by the Ogiek “complainants” in court proceedings for the African Commission on Human Rights and Peoples Rights Vs Republic of Kenya. Communication No.006/2012. Which helped them win the case on 26 May 2017. |

| 44 | Kenya Indigenous Forest Conservation Project (KIFCON) 1992. A consideration of strategies for settlement of the Okiek Ndorobo of South west Mau Forest, Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Nairobi. |

| 45 | An Ogiek People’s Ancestry and Territories (OPAT) Atlas for the Ogiek of Eastern Mau was published in 2011. With help from the discussions among Ogiek community members, the University of Bern together with their partners in an organization called Kenya Environmental Research Mapping and Information Systems in Africa (ERMIS), determined which critical features (e.g., hills, rivers, cultural areas), are considered as Ogiek clan territory. |

| 46 | According to Kanyinga, 1989, pp. 108–109 [66], “the skewed nature of the policy in favor of the Kikuyu was an issue of concern. Some of the settlements schemes were designed to satisfy the Kikuyu land hunger because they-Kikuyu, had the organization to destabilize the structure of landownership and the economy.” |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chabeda-Barthe, J.; Haller, T. Resilience of Traditional Livelihood Approaches Despite Forest Grabbing: Ogiek to the West of Mau Forest, Uasin Gishu County. Land 2018, 7, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040140

Chabeda-Barthe J, Haller T. Resilience of Traditional Livelihood Approaches Despite Forest Grabbing: Ogiek to the West of Mau Forest, Uasin Gishu County. Land. 2018; 7(4):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040140

Chicago/Turabian StyleChabeda-Barthe, Jemaiyo, and Tobias Haller. 2018. "Resilience of Traditional Livelihood Approaches Despite Forest Grabbing: Ogiek to the West of Mau Forest, Uasin Gishu County" Land 7, no. 4: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040140

APA StyleChabeda-Barthe, J., & Haller, T. (2018). Resilience of Traditional Livelihood Approaches Despite Forest Grabbing: Ogiek to the West of Mau Forest, Uasin Gishu County. Land, 7(4), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040140