1. Introduction

Given population growth and increasing pressures on land for human use [

1], there is an increasing global reliance on protected areas (PAs) as cornerstones of conservation strategies. This global emphasis on PAs is evidenced by the widespread support for the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD: an international treaty with 193 member countries) which, among other decisions, adopted the Aichi Biodiversity Target to protect 17% of the most biodiverse landscapes by 2020 [

2]. The establishment of national PA systems has been the globally preferred approach to biodiversity conservation in the 20th and 21st centuries. National PA systems around the world have rapidly increased from 141 areas covering less than 1% of Earth’s land area in 1911 to 130,709 areas and 13% global land coverage in 2011 [

3,

4] and 14.8% in 2016 [

5]. Furthermore, the rate of PA expansion has been growing: protected areas have increased nearly 80% from 1990 levels. Coordination of PAs worldwide has been greatly facilitated by The World Commission on Protected Areas, administered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which provides the following definition for a protected area:

“A protected area is a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated, and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values”.

This definition encompasses a variety of types of PAs, classified by management objectives [

7] and most recently by governance type [

8]. One of the current challenges for many developed nations is to pursue strategic expansion of their PA systems through diversification of management and governance mechanisms [

9].

As of 2016, Canada has achieved protection of approximately 10.5% of its terrestrial and inland water area [

5] (

Table 1). More than 85% of Canada’s PAs are classified as IUCN management categories I–IV [

9], which prohibit industrial activities such as mining, forestry, and hydro development. Furthermore, much of the area protected exists in large PAs in excess of 3000 km

2 [

9]. Canada is one of the few nations with the potential to protect large, intact landscapes, particularly in the boreal and arctic regions that are expected to be under increasing pressures based upon a number of future climate change projections [

10,

11]. Ultimately, a key factor in the ability of Canadian PA systems to protect their biological resources is the sustained ecological integrity of the individual PAs. Given the existing level and location of protection, combined with the fact that many additional areas are currently in de facto protection [

12], Canada has an opportunity unique among developed nations for a fundamental expansion of high-value, nondegraded protected areas. Furthermore, there is a strong willingness for comprehensive conservation planning owing to recent multi-stakeholder cooperative agreements and increasing political will [

13] and objectives reported in the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy to meet the 17% area target by 2020 ([

14], p. 48) agreed to under the Convention on Biological Diversity and related Aichi target [

2].

The goal of this research is to highlight opportunities and avenues for expanding Canada’s terrestrial PA system. The areas protected by province and territory are summarized in

Table 1, whereas the areas protected by federal agencies are summarized in

Table 2. We motivate our work with a description of the national context for PAs in Canada and provide examples focused on Canada’s nationally dominant (>550 Mha) and ecologically important boreal forests. We then provide relevant background on the science of conservation planning, the application of ecological concepts to PA selection and management, and the application of IUCN PA categories in Canada. We offer guidelines to present opportunities regarding the expansion of PA systems derived from both national and international examples. Finally, we present two hypothetical scenarios for doubling protection that build on the current mix of IUCN PA categories at national and ecozone scales.

2. Background for Protected Areas in Canada

Canada has a history of protected area designation, management, and governance with the establishment of its first national park (Banff) in 1885 and its first provincial park (Ontario’s Algonquin) in 1893. The federal government established Parks Canada (then the Dominion Parks Branch) as the World’s first government protected area organization, in 1911 [

15]. National and provincial parks are the most common types of protected areas in Canada, yet within the boreal region alone there are more than 70 types of PAs [

9] that play various cultural and ecological roles. The balance among the various PA roles has evolved over time from a recreational focus towards an ecological one. Concurrently, the source of the dominant threats to PAs has also changed from internal sources, such as heavy visitation rates, to external ones, including overdevelopment of the surrounding landscape, climate change, invasive species, and airborne pollution [

16]. See

Table 3 for an overview of IUCN management categories including codes, descriptions, and Canadian examples.

As Canada contemplates PA expansion, it is worth noting that relative to other nations, Canada has a disproportionately large level of PAs that are in strictly protected classes [

9]. National parks (IUCN Level II, see

Table 4) comprise ~48% of Canada’s PAs by area [

17], and the evolution of its park system policies provide supporting evidence of the shift toward an ecological focus on protection. The shift began with the 1964 comprehensive statement of national parks policy, whose main purpose was to clarify ambiguity in the National Parks Act originally passed in 1930. The policy shift asserted that the fundamental role of national parks was to be one of protection rather than use [

15]. This principle of ecological integrity was subsequently legally formalized in an amendment to the National Parks Act in 1988. The first National Park System plan was approved in 1971 to guide park expansion under a more systems-based approach. The emphasis was to increase representation of the 39 natural regions of Canada within the park system. As a result, given that roughly three quarters of the area within the national park system was designated after 1971, the majority of the park system was delineated within a value system that emphasized ecological integrity and representativeness. The mosaic of the larger set of all Canadian protected areas is more complicated, however, with management and governance carried out by diverse federal, provincial, and territorial agencies (

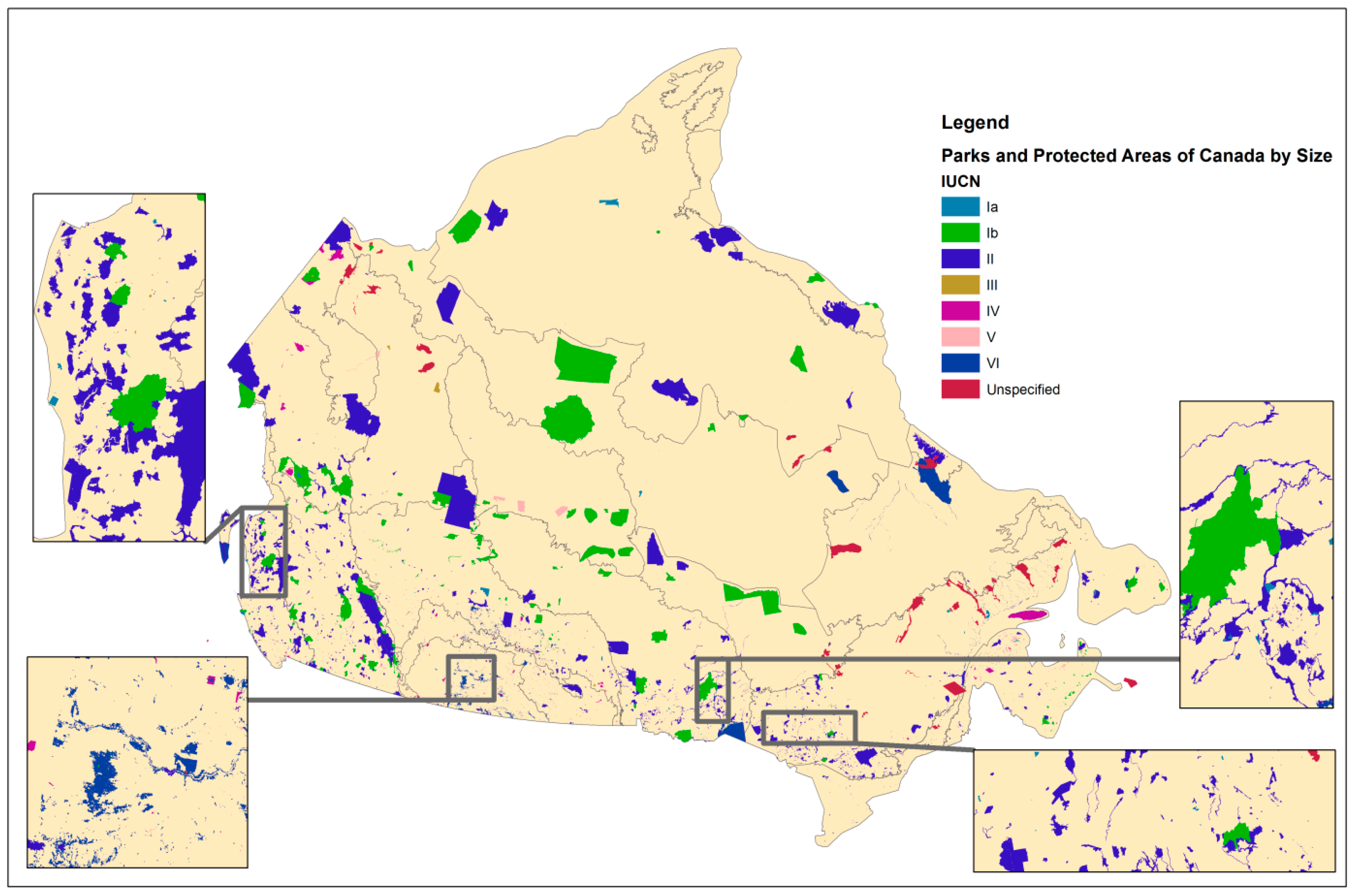

Figure 1;

Table 1) as well as First Nations and private land owners (

Table 2) [

5].

Canada’s terrestrial PA system is poised for expansion for several complementary reasons: (1) to ensure representation and persistence of Canadian biodiversity; (2) to align with global protection levels and targets; and (3) to formalize the protection of de facto protected areas [

12]. Recent studies have demonstrated the biases and underrepresentation of the current Canadian PA systems using a variety of biodiversity subsets and surrogates such as disturbance-sensitive mammals [

19], species at risk [

20], and productivity [

21]. The disproportionate distribution to strictly protected IUCN categories shows an opportunity to employ some of the other IUCN classes, which would offer some flexibility in PA assignment, while remaining within international norms. As a consequence, many different jurisdictions are concurrently working to expand Canada’s PA systems (e.g., [

22]). Demonstrating an ongoing capacity for expansion, the total amount of protected area in Canada has more than doubled from 5.2% in 1990, to 10.5% in 2016 [

5]. Many protected area management agencies have explicit expansion objectives. Nationally, Parks Canada is expanding with the objective of having at least one national park in each of Canada’s 39 natural regions. There are currently 11 natural regions unrepresented in the national park system although some have interim protection [

23]. Provincially, Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy sets a target to have 17% of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems protected in line with the Aichi global target [

2].

5. Expansion Scenarios for Canada’s Protected Area Systems: An Example in the Boreal

The protected area targets suggested specifically for Canada range from 12% [

66,

67], to 20% [

68], to 50% [

69]. Canada’s PAs are neither balanced in terms of total amount protected, proportion protected, nor balance among IUCN types. For the boreal region specifically, the balance among IUCN types differs substantially across the ecozones (

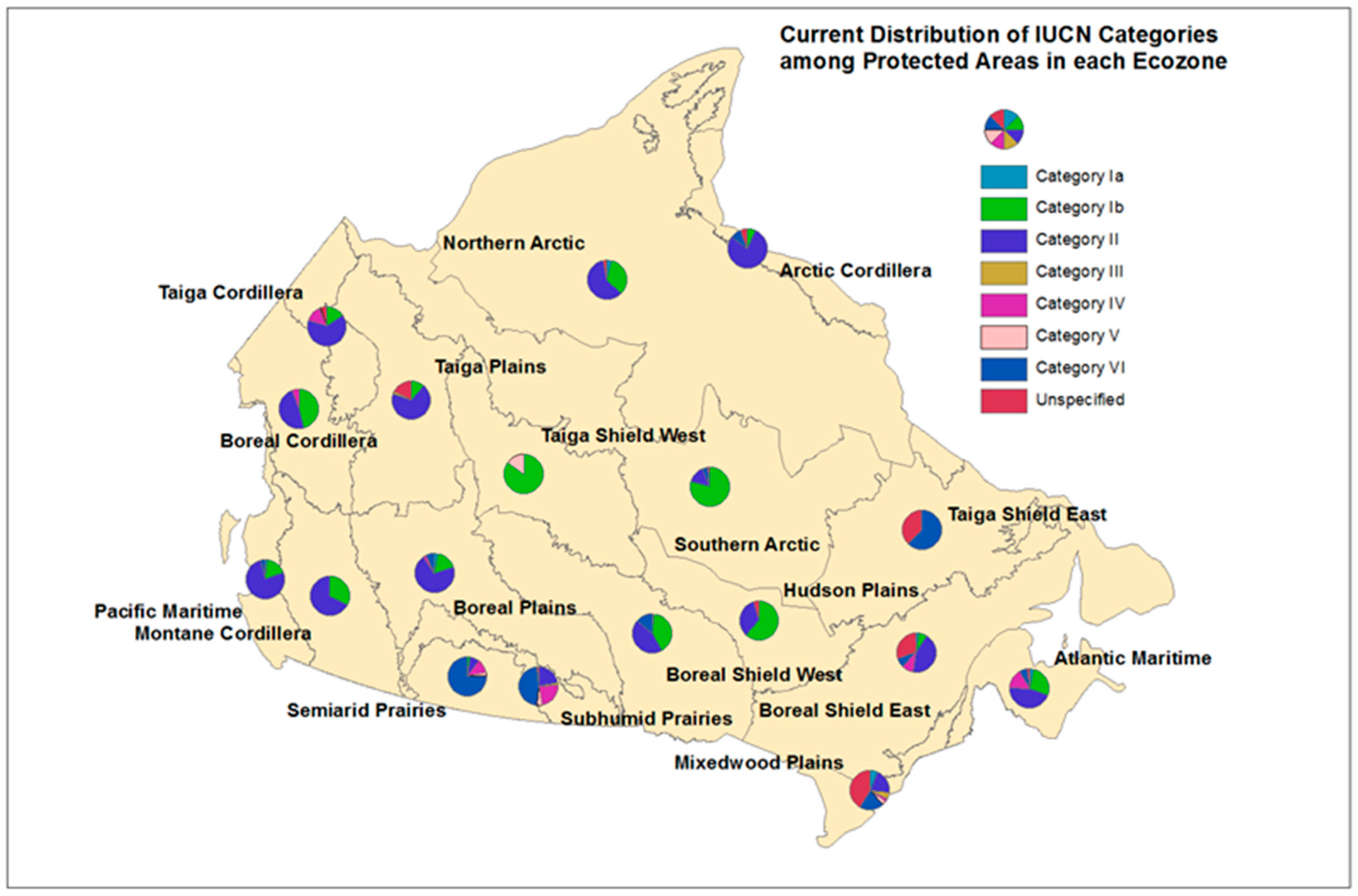

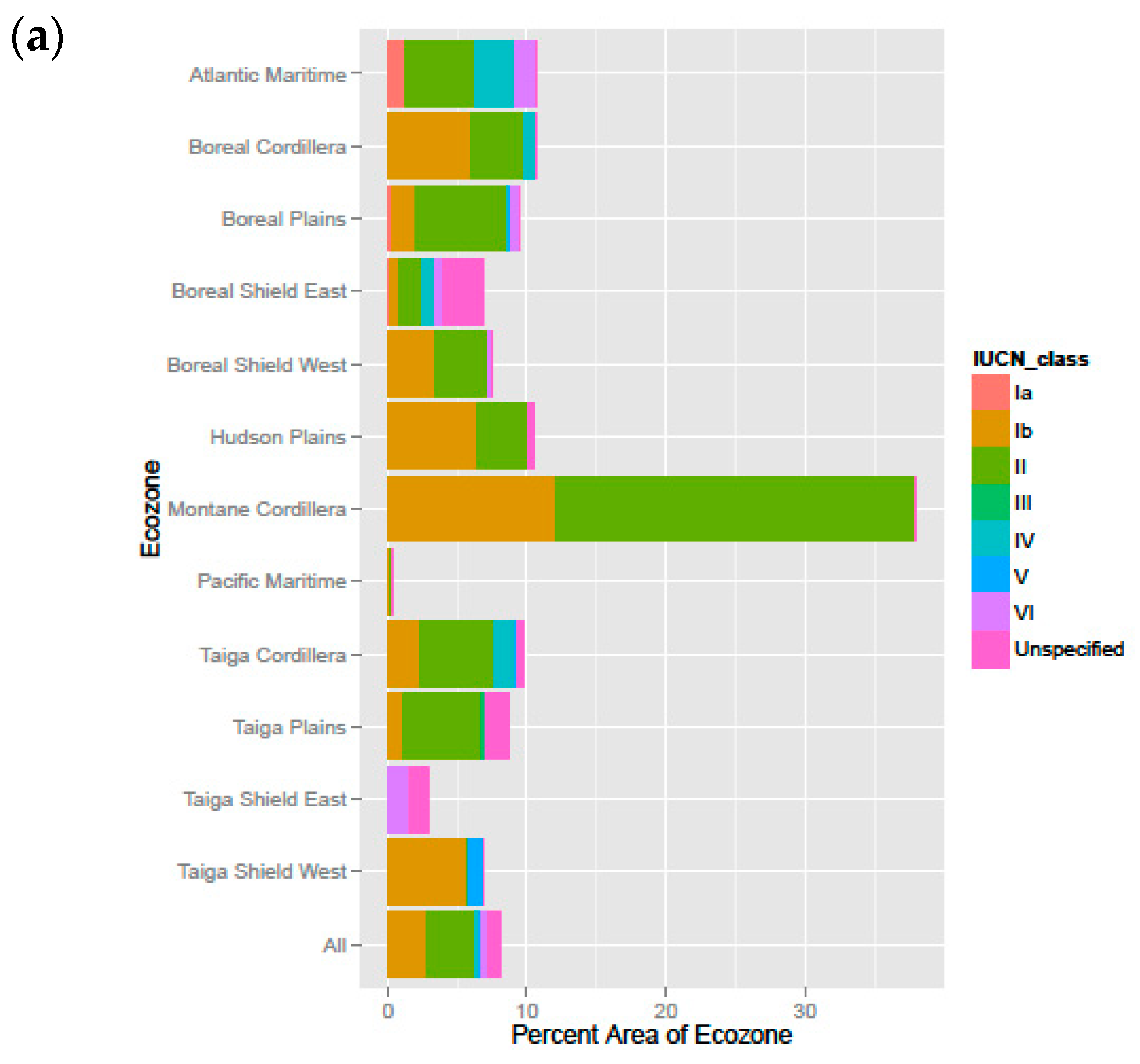

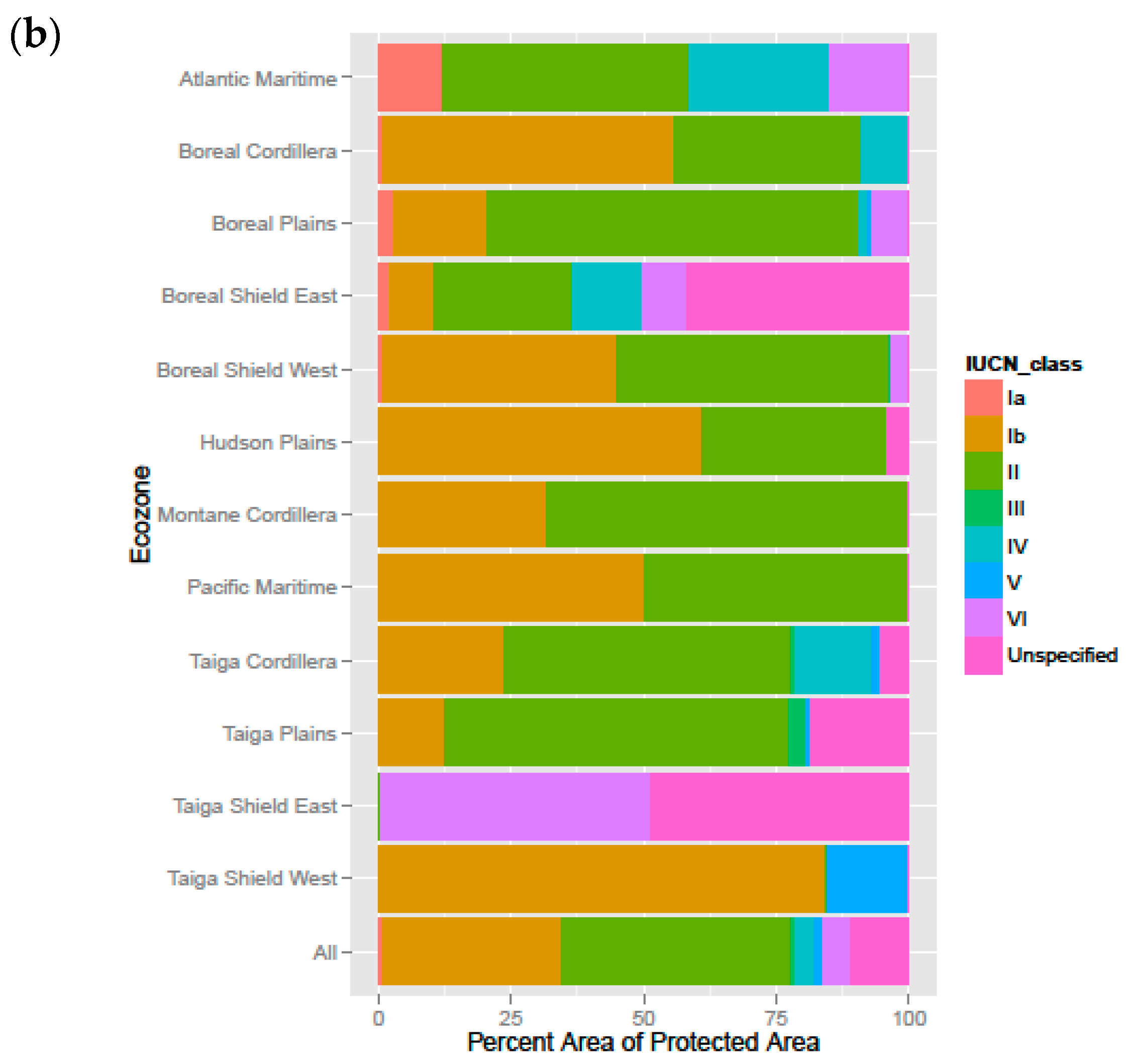

Figure 3b). Two notably large and underprotected ecozones are Boreal Shield East and Taiga Shield East, which currently protect 7% and 3% of their large areas respectively. Expansion to the current 17% federal target [

14] in these ecozones is made possible by the de facto opportunities for protection in the boreal relative to the more heavily populated areas further south [

12,

48], which may have more restrictive pre-existing land-use commitments [

9]. The 17% scenario currently under consideration represents more than a doubling of the 8% of the boreal currently under protection (

Figure 3a).

Due to political, economic, and social factors that are a necessary part of conservation in practice, there are circumstances in which a government may be limited in its ability to employ systematic, quantitative methods for identifying areas for protection. In those cases, governments may consider other approaches to guide the expansion of PA systems. Two potential approaches (among many) towards expanding Canada’s protected areas would involve (i) expanding the area of existing IUCN categories or (ii) expanding the range of IUCN categories within the PA system (while also increasing the area under protection). The first approach would maintain the same types of IUCN categories that are currently found within each ecozone, and focus on expanding the areas represented by each of these categories. For the boreal example, this would result in more IUCN category Ib (wilderness areas) and II (national parks), as these are currently the most prevalent IUCN categories currently found in the boreal. An alternative approach would be to broaden the range of IUCN categories that are currently represented in each ecozone, thereby introducing new models of protection that are tailored to regional conditions.

6. Opportunities and Conclusions

Currently, PA systems in Canada are dominated by relatively large PAs with strict protection in comparison with other countries. This is especially true for protection in Canada’s forested ecosystems where Categories Ib and II make up 80% of all PAs and 34 PAs are larger than 3000 km

2 [

9]. Nonetheless, only a small fraction of PAs in Canada meet the size requirements to maintain minimum viable populations of large, wide-ranging mammals or to protect landscape dynamics and natural disturbance regimes [

9]. A resilient PA network consists of multiple types of PAs including a system of representative core areas, corridors, stepping stones, and buffers. In this research, we posit that strategic expansion of protection in Canada could benefit from diversification of PA types to make greater use of less restrictive PA types (IUCN Categories V and VI). This would extend biodiversity conservation values across the landscape while strengthening connections among existing PAs. We encourage an ongoing dialogue about PA system diversification by providing Canadian interpretations of IUCN management and governance categories for PAs along with Canadian and international examples of their application. Towards this goal, our synthesis of the literature and current context in Canada indicated the following opportunities.

1. Canadian interpretation and implementation of IPA

International examples of IPA offer insights for implementation in Canada. National circumstances inform the nature of governance possible from IPA. For instance, agreements between Indigenous traditional owners or custodians in Australia have resulted in voluntary stewardship agreements that now result in 30% of national PA. The IPA designation is relatively new, with formal recognition in 1997, leaving opportunities for definition and implementation in a Canadian context. IPA can be created over a number of IUCN categories, although most frequently those (e.g., Categories V, VI) that allow for some human–nature interaction or sustainable resource use.

2. Identify and augment private PAs

An important next step to inform PA system diversification will be to identify opportunities for private PAs. We propose mapping privately owned lands within de facto PAs [

12] to determine candidate private PAs. As a second step, the map of candidate PAs should be assessed for their complementarity to the existing PA portfolio [

47], particularly within its ecozone. This assessment would be based on the degree to which candidate PAs contribute to the representativeness and effectiveness of the PA system and their degree of irreplaceability. Private lands offer opportunities for PA expansion through provision of habitat and harbors for endangered or threatened species [

70]. Knowledge of the ecological contribution of private lands can be combined with cultural, economic, and sociopolitical considerations to designate new PAs.

3. Clarify IUCN categories of PAs

Reporting IUCN categories for PAs is particularly challenging because the data is dispersed across the different governing agencies, noting that there are guidebooks to help standardize the assignment of IUCN categories [

6,

28]. However, despite best efforts, the present assignment of protected areas to IUCN categories globally does not correspond to the expected gradient of naturalness [

29]. The management and governance categories discussed herein can help to enhance biodiversity representation and persistence by identifying balanced solutions when working with diverse rights holders and stakeholders, as well as considering formalizing protection of large, de facto PAs. Future work will also require assigning PAs to governing categories that may prove even more challenging since PA governance may be subject to change over time.

4. Value connectivity in PA assessments

Maintaining and enhancing the connectivity of protected landscapes will be critical as climatic change redistributes species habitats [

71] and alters the frequency, extent, and intensity of disturbances [

72]. This may be especially (though not exclusively) relevant in boreal regions, where disturbances can be large and contiguous [

73]. For species to respond to climate-induced changes and maintain viable populations, PA systems must be conscious of the evolutionary continuum [

74] and designed to allow for broad-scale traversability of the landscape. Improving the connectivity among PAs is a way to increase the persistence of biodiversity across the network of PAs. Recent work across large areas, including with Zonation [

47,

75] and circuit theory [

76,

77,

78] point toward spatial data informed decision support tools that explicitly consider a variety of measures of connectivity.

5. Consider tradeoffs

Systematic conservation planning [

79] will require the a sophisticated understanding of a wide number of tradeoffs among multiple actors. As planners contemplate PA expansion, they can consider some of the following tradeoffs: biodiversity representativeness versus ease of implementing protection across different ownerships; the economic costs of implementing protection on private lands and public perception of payments; the tradeoff between connecting existing PAs versus protecting isolated but important habitats; tradeoffs between megafauna-heavy conservation areas and other important ecological criteria; tradeoffs between different aspects of biodiversity; and tradeoffs between known critical needs of today versus the less certain estimated needs of tomorrow.

6. PA data

Any future research extending the scope of this research should begin by revisiting the PA data used for this analysis. Conservation Areas Reporting and Tracking System [

24] is the primary source for information on Canada’s PAs. It is unclear, however, to what extent this source is consistent with other sources such as Environment Canada’s Environmental Indicators on Protected Areas and the World Database on Protected Areas. Many countries are currently in the process of putting in place formalized reporting structures for PAs. Canada is relatively advanced in this regard although we suspect that the reporting of private PAs is less consistent than that of public PAs.

Protection of natural spaces for habitat, wildlife, and provision of ecosystem services are an important component of land and forest management. Given the stated national target, that “by 2020, at least 17% of terrestrial areas and inland water are conserved through networks of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures” [

5] (p. 45); this is a critical period in the history of Canadian land/water management. Ongoing technological advances in remote sensing, GIS, and modeling have made it newly possible to analyze the state of Canada’s many landscapes, model the impacts of management decisions, and plan for the future. As a number of different stakeholders and rights-holders collaboratively map current and future land uses onto forest landscapes, science-based conservation targets and spatial prioritizations must be ready and accessible to inform this process. To this end, we have provided an overview of the theoretical framework of spatial conservation prioritization rooted in ecological concepts. By synthesizing the relevant literature in the Canadian context, our objective was to highlight the opportunities available to expand protected areas in Canada, while also broadening engagement and recognizing that conservation is not one-size-fits-all. This work offers a source of options and opportunities to inform conservation agencies with ideas, options, and approaches to expand Canada’s PA systems. Multiple actors and agencies, each working within their own stewardship constraints and opportunities, can combine to respond to the stated national priority of protecting more of Canada’s natural area.