Urban Street-Scene Perception and Renewal Strategies Powered by Vision–Language Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

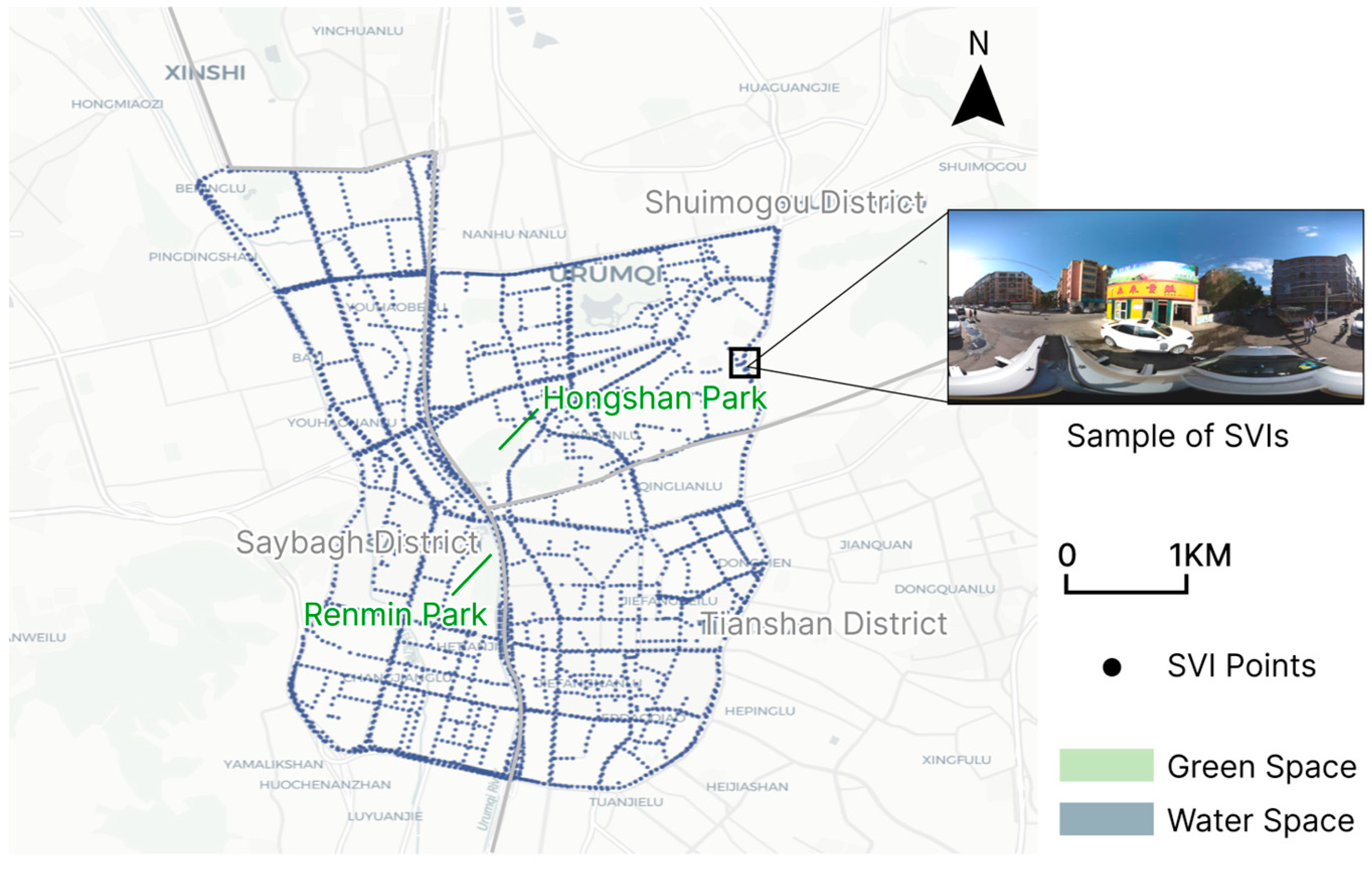

2.1. Study Area

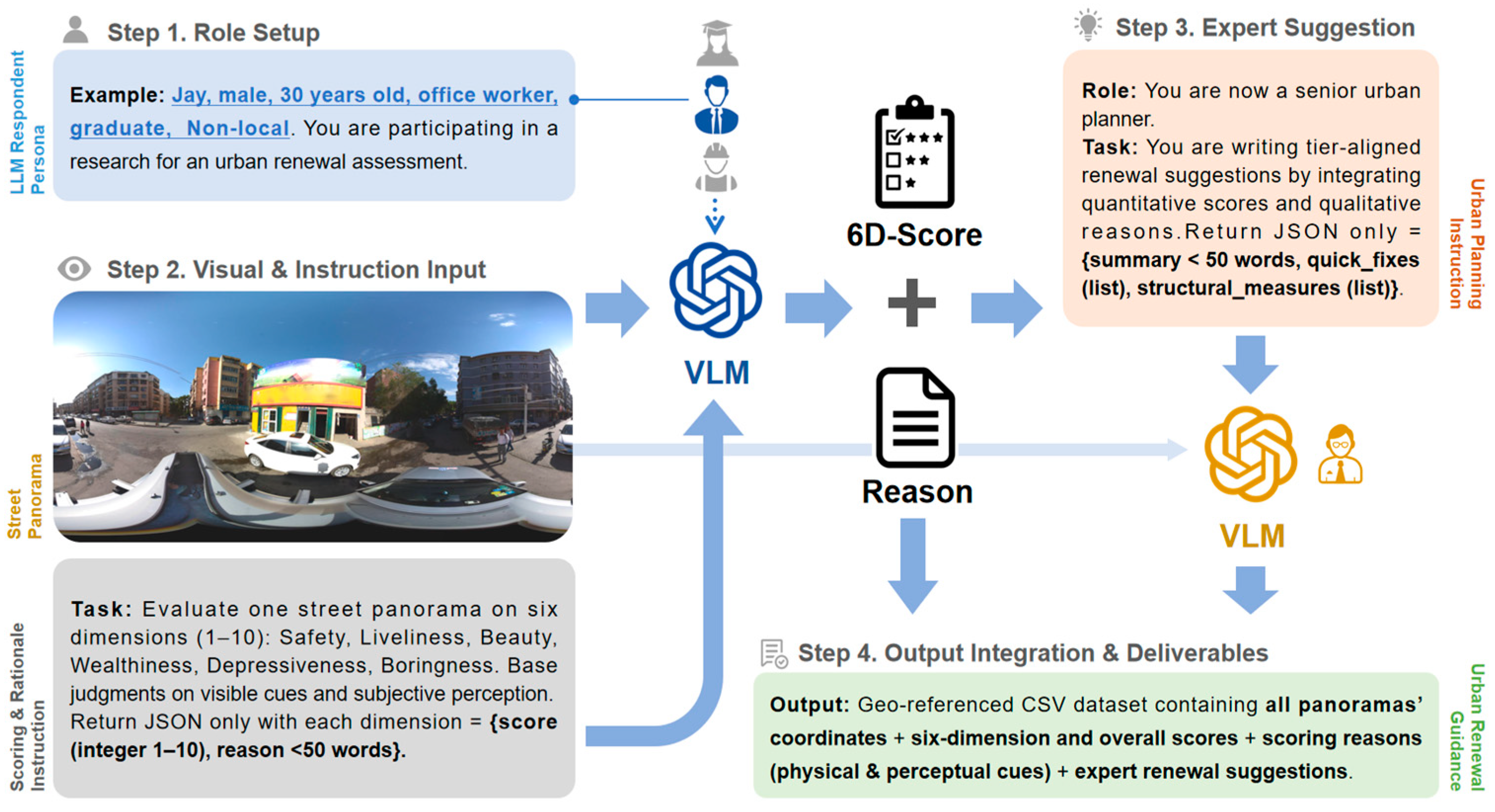

2.2. VLM Selection and Prompt Design

2.3. Human Labeling and Result Validation

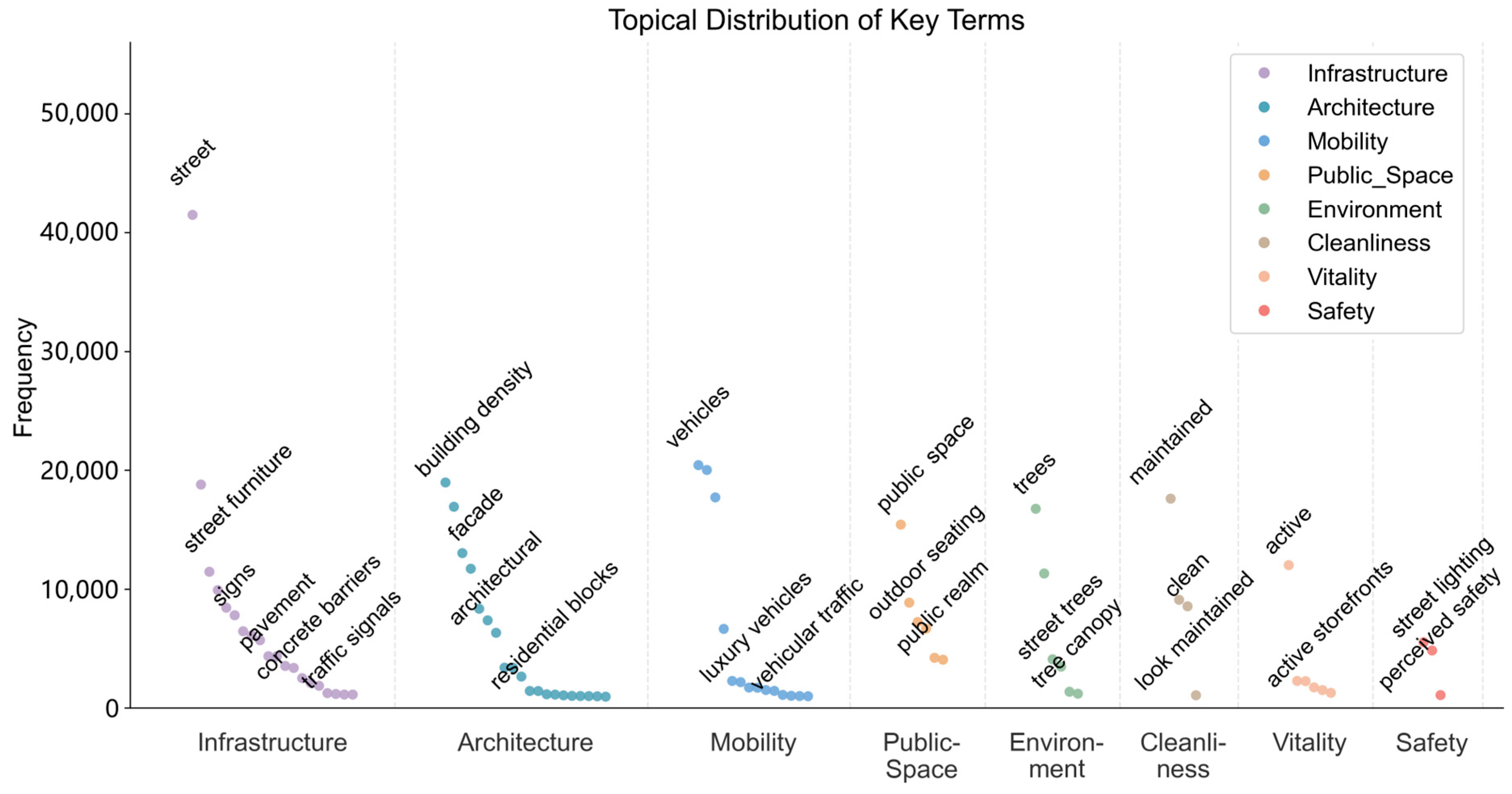

2.4. Analysis of Model-Generated Explanations

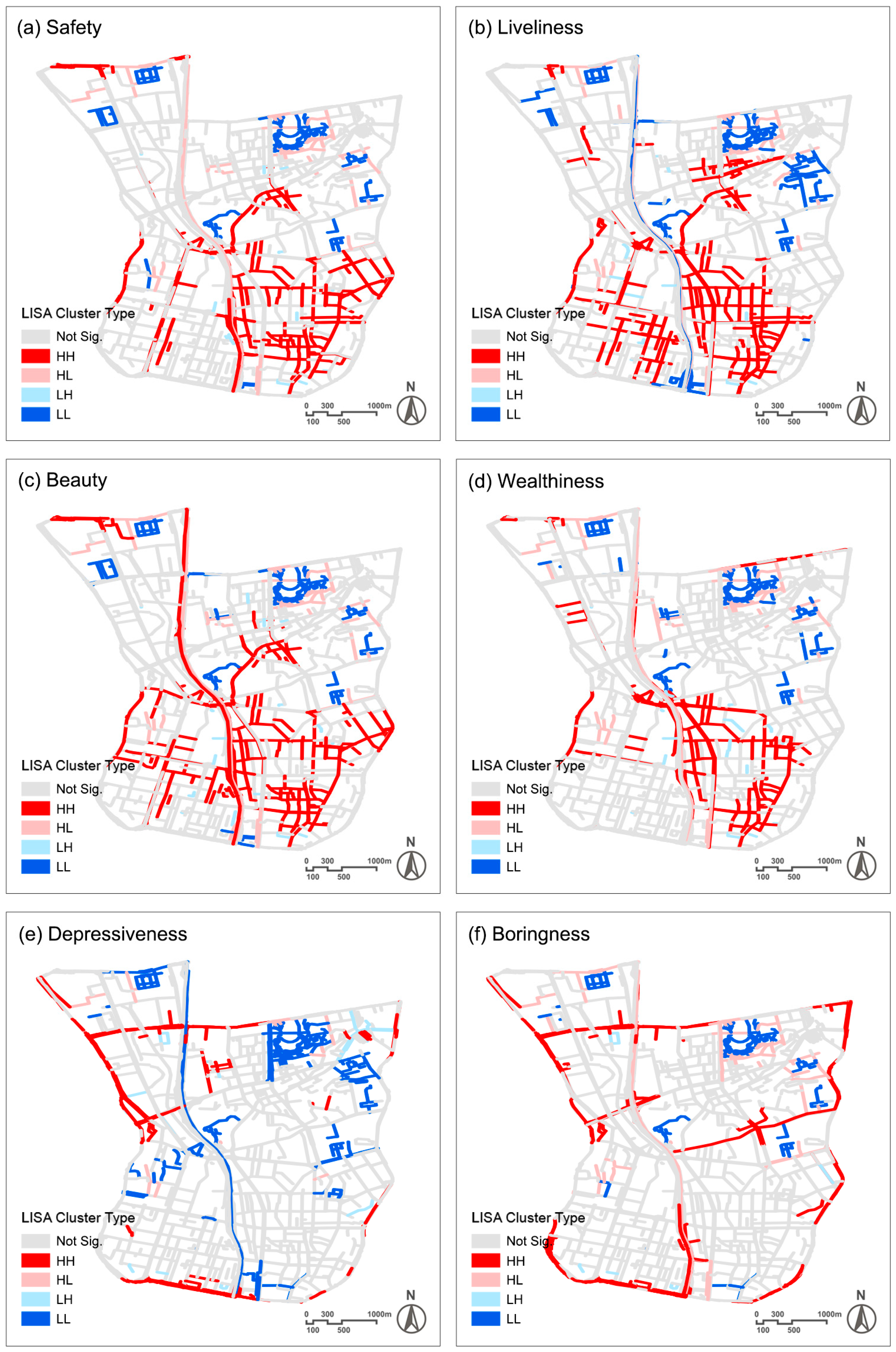

2.5. Spatial Analysis

3. Results

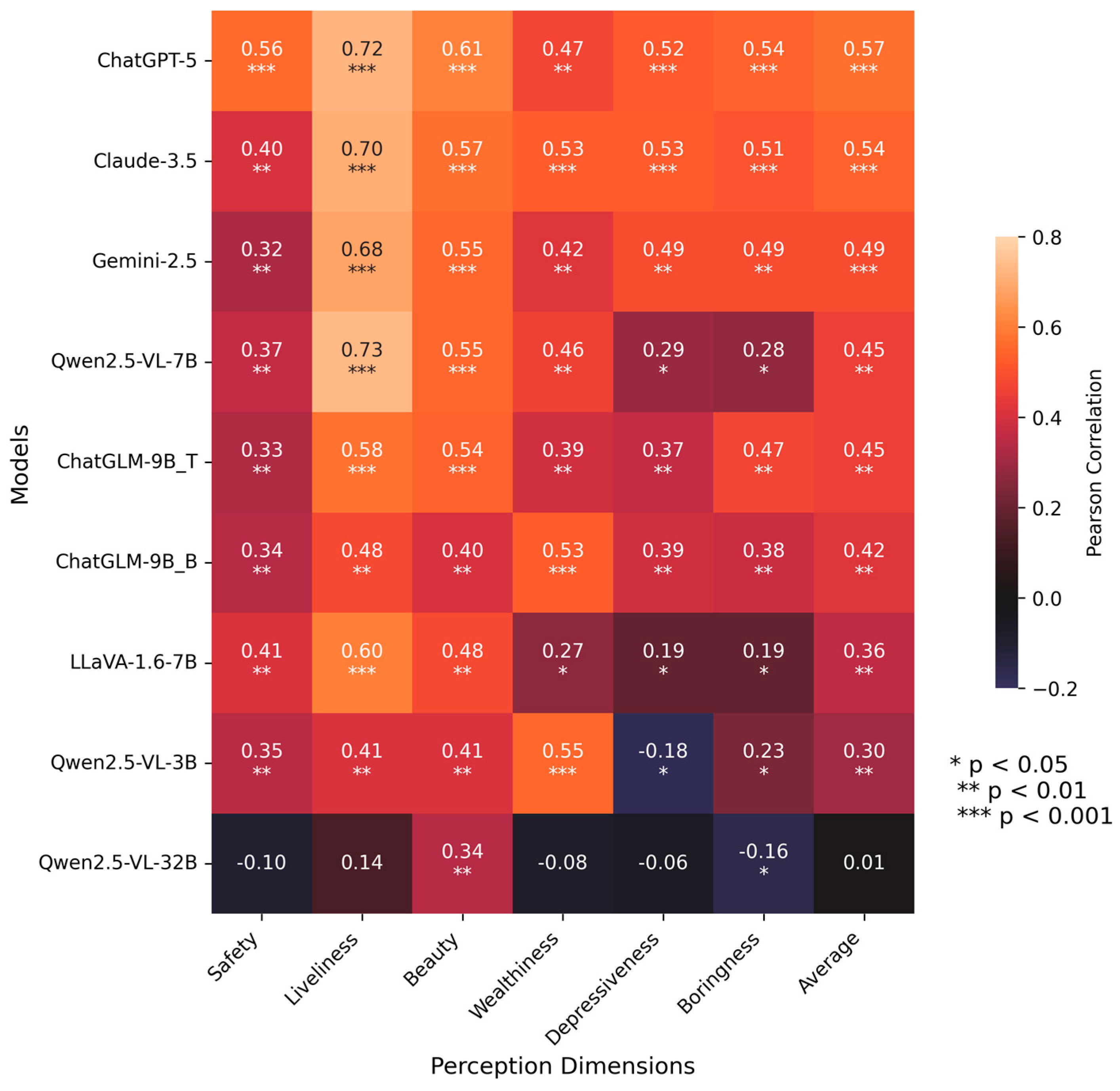

3.1. Model Selection and Accuracy Validation

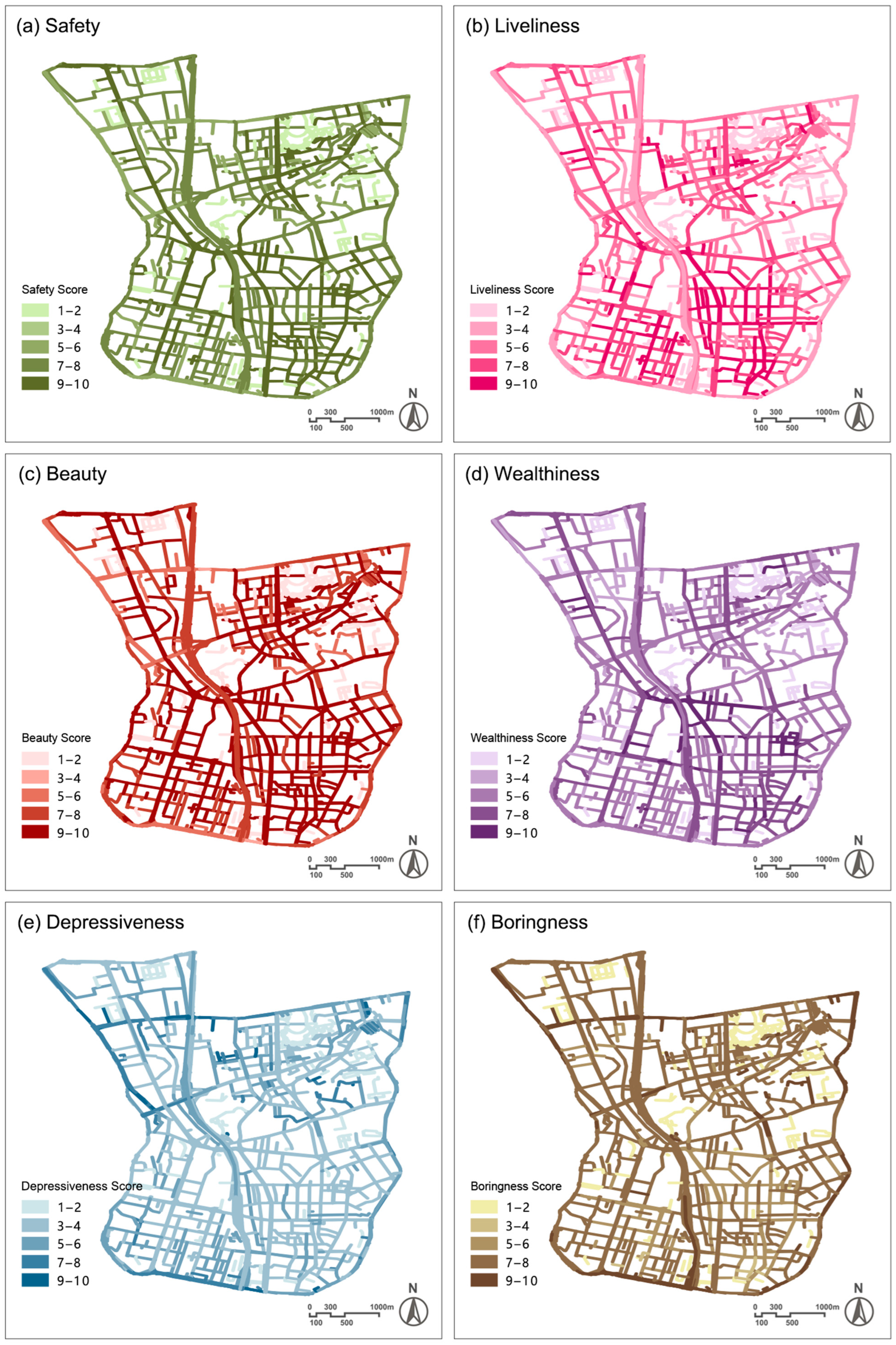

3.2. Spatial Distribution of Perception Scores

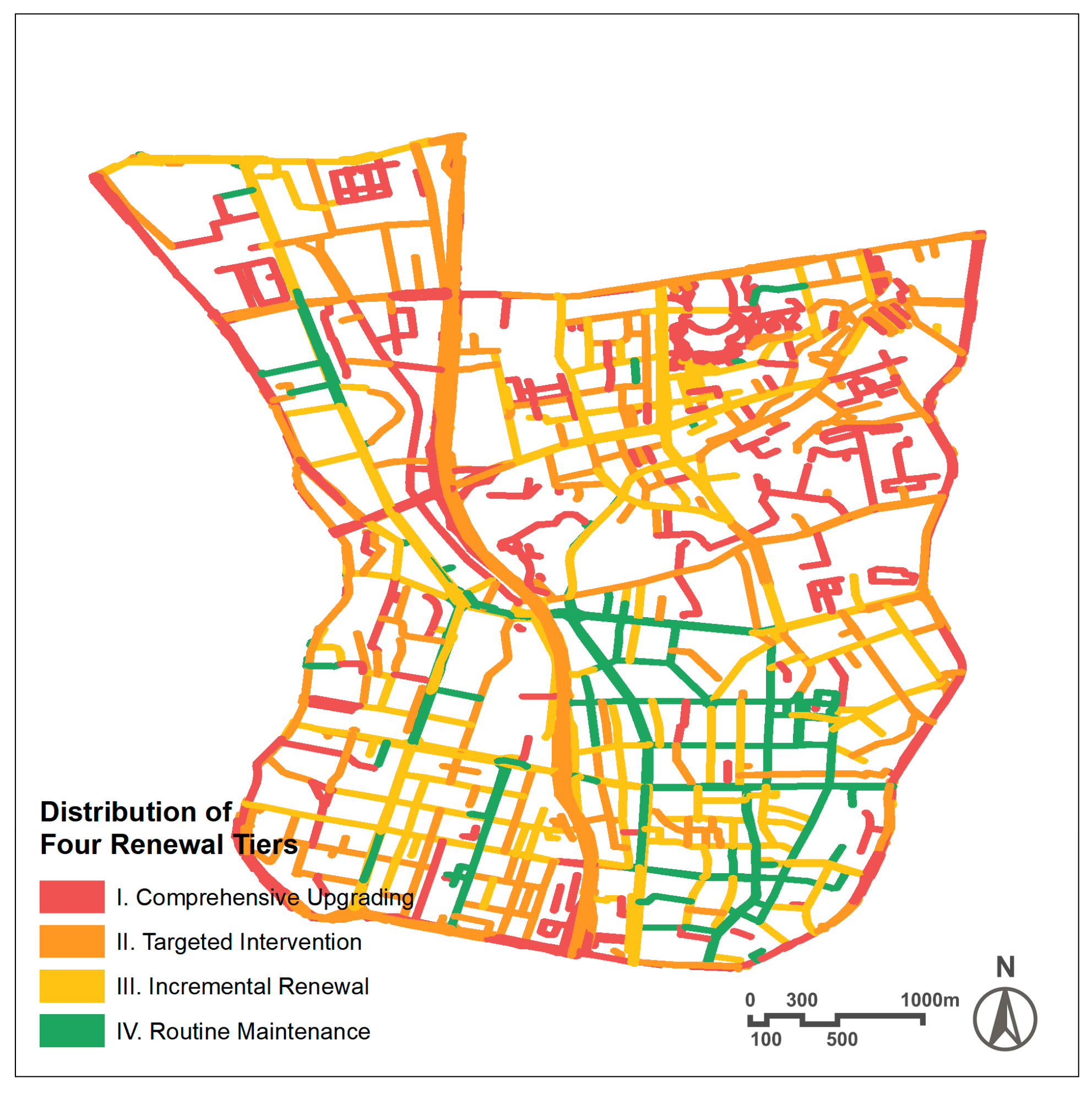

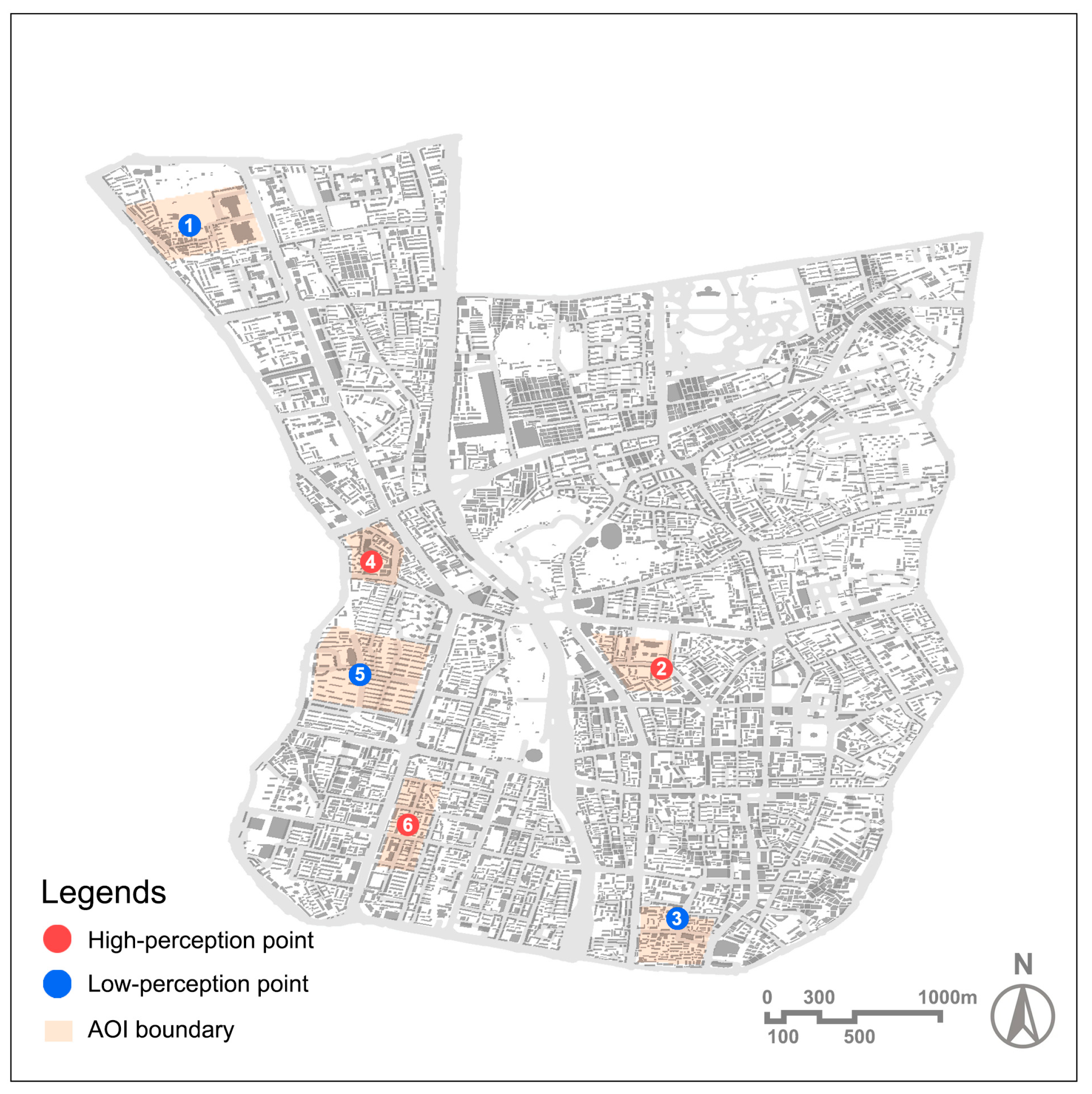

3.3. Identification of Renewal Priority Tiers

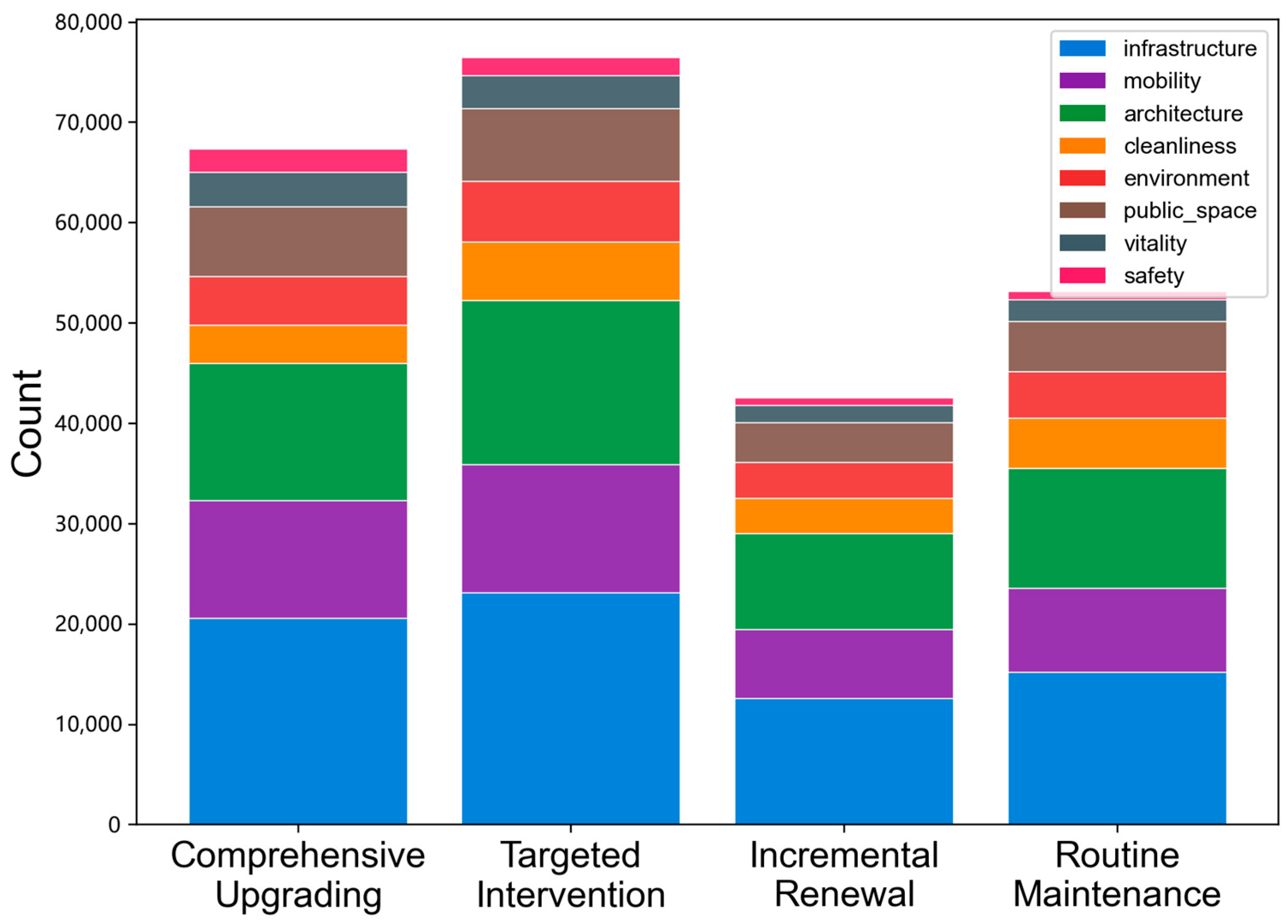

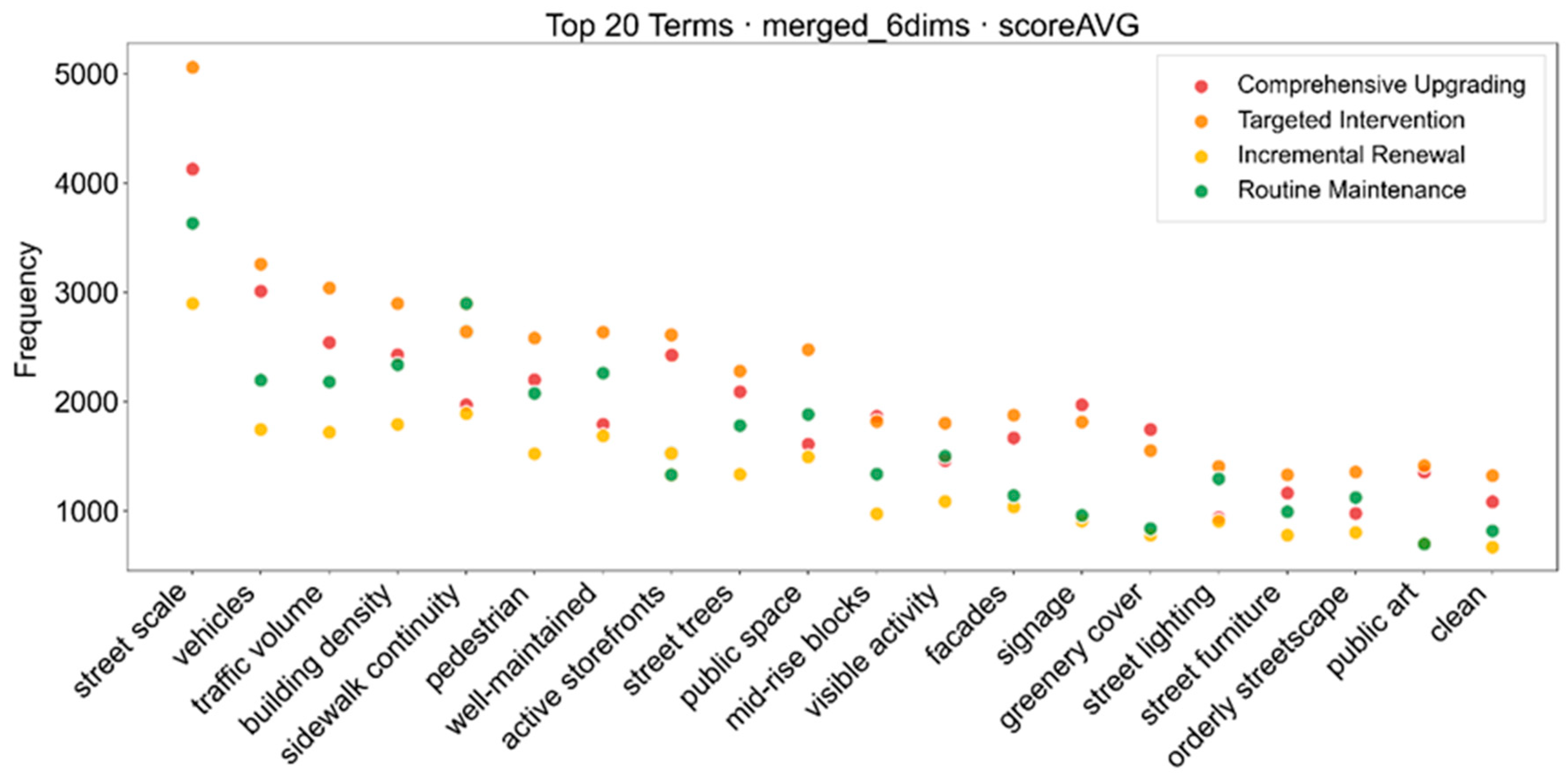

3.4. Semantic Analysis of Street-View Descriptions

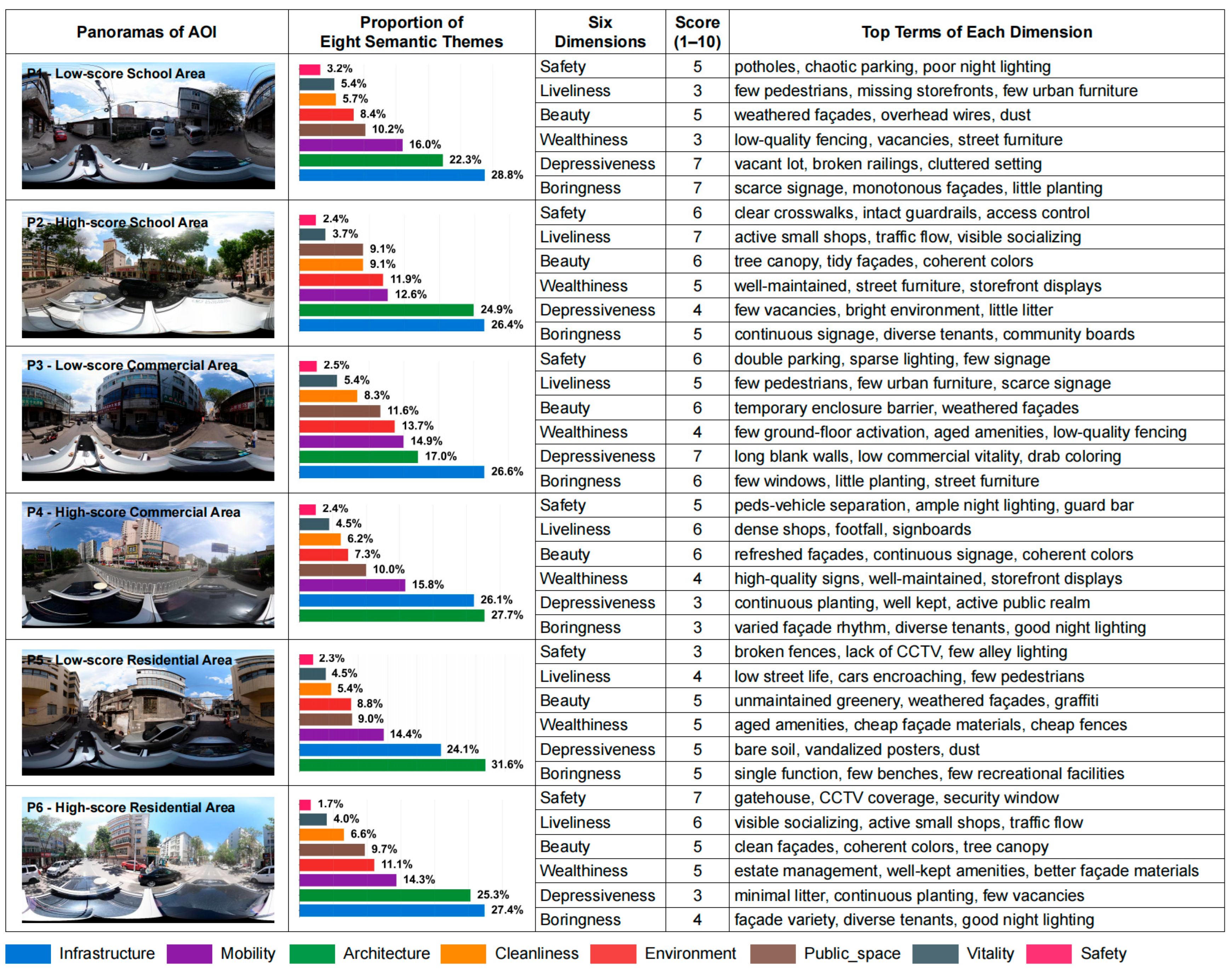

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Representative Sites

4. Discussion

4.1. Consistency Between VLMs and Human Perception

4.2. The Value of VLM Interpretability for Urban Renewal

4.3. Theoretical Implications and Practical Applications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VLM(s) | Vision–Language Model(s) |

| LLM(s) | Large Language Model(s) |

| SVI(s) | Street-View Image(s) |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| AOI(s) | Area(s) of Interest |

References

- Deng, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, B.; Shi, Y.; Deng, M.; Liu, E. Renovation and Reconstruction of Urban Land Use by a Cost-Heuristic Genetic Algorithm: A Case in Shenzhen. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X. Coupling Coordination Analysis and Factors of “Urban Renewal-Ecological Resilience-Water Resilience” in Arid Zones. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1615419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Hu, Y.; Li, M. Chinese Pattern of Urban Development Quality Assessment: A Perspective Based on National Territory Spatial Planning Initiatives. Land 2021, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Huang, C.; Wang, P.; Ma, J.; Wan, Y. Identification of Inefficient Urban Land for Urban Regeneration Considering Land Use Differentiation. Land 2023, 12, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; Publication of the Joint Center for Urban studies, 33. print.; M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-262-62001-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage books ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kelling, G.L.; Wilson, J.Q. Broken Windows: The police and neighborhood safety. Atl. Mon. 1982, 249, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Marini, S.; Mauro, M.; Maietta Latessa, P.; Grigoletto, A.; Toselli, S. Associations Between Urban Green Space Quality and Mental Wellbeing: Systematic Review. Land 2025, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Ji, X.; Sun, D.; Meng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lyu, M. Impact of Streetscape Built Environment Characteristics on Human Perceptions Using Street View Imagery and Deep Learning: A Case Study of Changbai Island, Shenyang. Buildings 2025, 15, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zeng, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W. Urban Perception Evaluation and Street Refinement Governance Supported by Street View Visual Elements Analysis. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V. Lively Streets: Determining Environmental Characteristics to Support Social Behavior. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2007, 27, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Oki, T.; Zhao, C.; Sekimoto, Y.; Shimizu, C. Evaluating the Subjective Perceptions of Streetscapes Using Street-View Images. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 247, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, P.; Bie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Guan, Q. A Human-Machine Adversarial Scoring Framework for Urban Perception Assessment Using Street-View Images. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 2363–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Ito, K. Street View Imagery in Urban Analytics and GIS: A Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 215, 104217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesses, P.; Schechtner, K.; Hidalgo, C.A. The Collaborative Image of The City: Mapping the Inequality of Urban Perception. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Naik, N.; Parikh, D.; Raskar, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. Deep Learning the City: Quantifying Urban Perception at a Global Scale. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, T.; Cui, C.; Yin, Y. Deep Semantic-Aware Network for Zero-Shot Visual Urban Perception. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cyber. 2022, 13, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Haworth, J.; Wang, M. A New Approach to Assessing Perceived Walkability: Combining Street View Imagery with Multimodal Contrastive Learning Model. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Spatial Big Data and AI for Industrial Applications; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lu, Y.; Lin, G. An Integrated Deep Learning Approach for Assessing the Visual Qualities of Built Environments Utilizing Street View Images. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Gao, S.; Lin, H.; Liu, Y. A Review of Urban Physical Environment Sensing Using Street View Imagery in Public Health Studies. Ann. GIS 2020, 26, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Vera, F.; Poco, J. Assessing Urban Environments with Vision-Language Models: A Comparative Analysis of AI-Generated Ratings and Human Volunteer Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rome, Italy, 30 June–5 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Cui, W.; Ji, Q.; Xing, H. Evaluation of Spatial Visual Perception of Streets Based on Deep Learning and Spatial Syntax. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-VL Technical Report. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bai, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z.; Bai, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; et al. Qwen2-VL: Enhancing Vision-Language Model’s Perception of the World at Any Resolution. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual Instruction Tuning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- GLM-V Team; Hong, W.; Yu, W.; Gu, X.; Wang, G.; Gan, G.; Tang, H.; Cheng, J.; Qi, J.; Ji, J.; et al. GLM-4.5V and GLM-4.1V-Thinking: Towards Versatile Multimodal Reasoning with Scalable Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, C.A.; Pickle, L. Evaluation of Methods for Classifying Epidemiological Data on Choropleth Maps in Series. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2002, 92, 662–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat (Ed.) The Value of Sustainable Urbanization; World cities report; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann, F.A.; Geirhos, R. Are Deep Neural Networks Adequate Behavioral Models of Human Visual Perception? Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2023, 9, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushkani, R. Do Vision-Language Models See Urban Scenes as People Do? An Urban Perception Benchmark. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ge, J.; He, W. Quantifying Urban Vitality in Guangzhou Through Multi-Source Data: A Comprehensive Analysis of Land Use Change, Streetscape Elements, POI Distribution, and Smartphone-GPS Data. Land 2025, 14, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ma, J.; Tang, Y.; Yang, T.; Jiang, F. Can We Trust Our Eyes? Interpreting the Misperception of Road Safety from Street View Images and Deep Learning. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 197, 107455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, T.; Krause, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Deng, J.; Aiden, E.L.; Fei-Fei, L. Using Deep Learning and Google Street View to Estimate the Demographic Makeup of the US. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 13108–13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torneiro, A.; Monteiro, D.; Novais, P.; Henriques, P.R.; Rodrigues, N.F. Towards General Urban Monitoring with Vision-Language Models: A Review, Evaluation, and a Research Agenda. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Chen, R.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Fang, Y. The Scale Effect of Street View Images and Urban Vitality Is Consistent with a Gaussian Function Distribution. Land 2025, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhao, T.; Biljecki, F. Revealing Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Urban Visual Environments with Street View Imagery. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | 18–30 years | 198 | 39.6 |

| 31–45 years | 186 | 37.2 | |

| 46–60 years | 116 | 23.2 | |

| Gender | Male | 247 | 49.4 |

| Female | 253 | 50.6 | |

| Residential Status | Locals | 342 | 68.4 |

| Non-locals | 158 | 31.6 | |

| Education Level | High school | 89 | 17.8 |

| Undergraduate | 276 | 55.2 | |

| Graduate | 135 | 27.0 | |

| Occupation | Students | 156 | 31.2 |

| Office workers | 189 | 37.8 | |

| Service industry | 78 | 15.6 | |

| Others | 77 | 15.4 |

| Perception Dimension | R2 | RMSE | MSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety | 0.319 | 0.544 | 0.295 |

| Liveliness | 0.517 | 0.654 | 0.427 |

| Beauty | 0.374 | 0.515 | 0.266 |

| Wealthiness | 0.221 | 0.612 | 0.375 |

| Depressiveness | 0.273 | 0.705 | 0.497 |

| Boringness | 0.291 | 0.583 | 0.340 |

| Overall Average | 0.332 | 0.602 | 0.367 |

| Perception Dimension | Moran’s I | Z-Score | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety | 0.441 | 25.216 | <0.001 |

| Liveliness | 0.490 | 27.942 | <0.001 |

| Beauty | 0.453 | 25.868 | <0.001 |

| Wealthiness | 0.463 | 26.420 | <0.001 |

| Depressiveness | 0.563 | 32.115 | <0.001 |

| Boringness | 0.478 | 27.269 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yao, Y.; Dall’Ò, G.; Lu, F. Urban Street-Scene Perception and Renewal Strategies Powered by Vision–Language Models. Land 2026, 15, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020244

Yao Y, Dall’Ò G, Lu F. Urban Street-Scene Perception and Renewal Strategies Powered by Vision–Language Models. Land. 2026; 15(2):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020244

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Yuhan, Giuliano Dall’Ò, and Feidong Lu. 2026. "Urban Street-Scene Perception and Renewal Strategies Powered by Vision–Language Models" Land 15, no. 2: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020244

APA StyleYao, Y., Dall’Ò, G., & Lu, F. (2026). Urban Street-Scene Perception and Renewal Strategies Powered by Vision–Language Models. Land, 15(2), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020244