1. Introduction

Sand dunes in coastal areas are remarkable ecosystems that play a primary role in protecting the inland from flooding, salinization prevention, defense of natural habitat, preservation of groundwater storage, and anthropic activities [

1]. Their dynamics and morphological equilibrium are driven by the complex interaction between different factors. Among other things, vegetation coverage, wind characteristics, and nearshore beach attributes are relevant [

2]. The climatic and anthropogenic pressures, connected with the highly dynamic factors of these elements, make the sand dunes in coastal areas extremely vulnerable [

3]. In this context, monitoring these fragile ecosystems and their geomorphological structures is crucial to preventing degradation and/or designing intervention strategies for risk mitigation in coastal areas.

Total station and leveling instruments [

4,

5], the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) [

6,

7], UAS-based structure-from-motion photogrammetry (SfM) and airborne laser scanning (ALS) [

8,

9,

10], terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) [

11], and handheld mobile laser scanning (HMLS) [

12] geomatic methods can be used to monitor the deformations of sand dunes since they provide georeferenced data with high resolutions and high accuracies.

Danchenkov et al. [

13] used the TLS technique to acquire six multitemporal point clouds and extracted digital elevation models (DEMs) of two coastal areas in the Curonian Spit National Park (Southeastern Baltic Sea) from autumn 2014 to spring 2016. The scans were aligned and georeferenced using the differential GNSS technique. The authors compared the multitemporal models quantifying the volume of material moved due to the coastal hydrodynamic processes. Prodanov et al. [

14] applied unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry with the structure-from-motion (SfM) technique to study the erosion-accumulation processes and coastline changes in the longest beach–dune system on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. The authors conducted 17 multitemporal UAV surveys in the 2020–2021 period, acquiring ground control points (GCPs) by means of the GPS real-time kinematic (RTK) approach (accuracies of 2–3 cm) for reference and the control of geodetic points. They generated DEMs and DEMs of differences. On the basis of the reliability and accuracy of the orthophotomosaics, the authors evaluated erosion and accretion by digitizing the shoreline in different time series. Similarly, Kelaher et al. [

15] acquired UAS-based imagery in the period 2019–2021 on Lord Howe Island (Australia) before and after a nourishment program. They monitored changes in beach nourishment using seven 3D data points, based on orthorectified images. However, in sand areas (beaches; dunes) with a homogeneous distribution of pixel radiometry that poorly identifies distinct pixel regions, the texture of the images may be a critical limitation on the quality of SfM photogrammetry [

16].

Geomatic techniques can be integrated: data acquired with sensors on different platforms have demonstrated an improvement in extracting high-resolution and high-precision information in the monitoring of deformations. Moreover, the combination of the different techniques provides a system greater than the sum of its parts [

17] and allows one to overcome their respective limitations [

18,

19]. Alexiou et al. [

20] used TLS and UAV in combination with georadar profiles (Ground-Penetrating Radar—GPR) and GNSS to quantify erosion and sedimentation due to wildfires in Greece. The authors obtained different 3D models with total registration errors from 1 to 5 cm. Marín-Comitre et al. [

21] combined terrestrial SfM and multiview–stereo photogrammetry, TLS, and aerial UAV SfM-MVS to model the geometry of the watering pond and estimate the relationships between volume, area, and height in the Iberian Peninsula. In addition, GNSS was used to acquire the morphological characteristics of inundated areas. The authors provided co-registered data with root mean square errors (RMSEs) at check points of about 2 cm, 9 cm, and 2 cm for terrestrial SfM, UAV SfM, and TLS, respectively. Kovanic et al. [

7] applied digital aerial photogrammetry, GNSS RTK (534 points), and TLS (the reference method) for the determination of heap volumes and documentation in Slovakia. The authors compared the 3D models extracted from each technique, which provided standard deviations of 3.9 cm and 4.2 cm (TLS—aerial photogrammetry) and 6.8 cm and 6.7 cm (TLS—GNSS RTK) in two areas. On the basis of these levels of accuracy, the integration of geomatic techniques can provide useful data in the monitoring of coastal sand dunes. Seymour et al. [

22] conducted unmanned aircraft system (UAS) (SfM approach), aerial, GNSS, and TLS surveys on 2 June 2016 at Bird Shoal and Bulkhead Shoal, part of an active fetch-limited barrier island and salt marsh complex in Beaufort Town, North Carolina, and the Duke University Marine Lab, US. The authors extracted digital surface models (DSMs) from each dataset and compared the 3D data in different conditions: finally, they obtained vertical differences in the order of a few centimeters, confirming the high level of accuracy that can be obtained in these complex coastal environments. De Sanjosé et al. [

23] monitored Somo beach on the Cantabrian coast, Spain, from 1875 to 2017, integrating historical cartography, photogrammetric flight series, classical topography, and georeferenced TLS data using the GNSS technique. By comparing the data over time, the authors estimated the evolution and erosive rhythms on the foredune, highlighting the advantages of using historical/archival data to reconstruct the morphological changes in coastal areas over a long time. Guisado-Pintado et al. [

24] applied UAV-SfM and TLS plus baseline differential GPS (DGPS) data points in a portion of a dune–beach system in Five Finger Strand, located on the north coast of County Donegal (Northwest Ireland), to assess the effectiveness and limitations of these techniques. In their analysis, the authors concluded that TLS provides better results over flatter, low-angled topography containing sparse or non-vegetated areas compared to areas with complex morphology, where shadow zones compromise the reliability of the final 3D models. Conversely, UAV-SfM provides good performance in different terrains, with the exception of low-angle morphology and featureless areas, such as sandy beaches and densely vegetated ground surfaces, where the differences between techniques are greater than 1 m. Many other applications can be found in the literature.

In the above-mentioned works, high-resolution and high-precision GNSS, TLS, and UAV photogrammetric/ALS surveys found significant applications in coastal areas for detecting and monitoring the displacements of coastline [

25,

26], monitoring the deformations of sand dunes and sand–beach areas [

27,

28,

29], and monitoring the accumulation of marine litter [

30,

31]. However, the use of HMLS in these complex coastal environments requires a more detailed study, including the analysis of comparability between aerial- and ground-based information acquired in vegetated areas.

Typically, an HMLS system, used indoors and/or outdoors, is composed of one or more laser scanners with an inertial measurement unit (IMU) and, in many cases, is equipped with a GNSS tracker that can provide real-time positioning of the acquired data [

32]. The HMLS technique offers clear logistical advantages over SfM photogrammetry and TLS for particular survey situations, thanks to the flexibility of the system and the ease of the real-time movement of the sensor for surveys in complex environments [

33]. An application of this technology on sand dunes, the Hovermap [

34], but mounted on a UAV, was carried out by Sofonia et al. [

35]. They used the sensor on a UAV platform, performing four surveys of a segment of coastal sand dunes on Bribie Island in Queensland (Australia), from July 2017 to April 2018. The authors also acquired the 3D data of the study area using a Leica P40 TLS system from nine locations as a comparative reference point cloud. The data collected by the Hovermap on the GCPs, measured with the network real-time kinematic (NRTK) approach, provided an RMSE of about 5 cm. Apart from this application, the use of HMLS systems in vegetated sand dunes has not yet been fully explored.

In order to provide a new methodological contribution in this study context, in this work, the HMLS technique was applied to the sand dune system of the Caleri coastal area (Po River Delta—PRD, northern Italy,

Figure 1) to evaluate the performance of this methodology in a complex environment. To this end, GNSS NRTK, UAS-based photogrammetry, and TLS surveys were performed to acquire 3D information for both the performance analysis of these techniques in vegetated sand dune systems and the level of applicability of the HMLS data. The information acquired from each technique was processed to extract the respective point clouds, georeferenced, validated, and compared with each other to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of these methodologies applied to the survey of sand dunes.

Data acquisition was carried out on 27 May 2024, when the sand dunes area was characterized by moderate/high elevation changes and clusters of dense vegetation (

Figure 1d). The photogrammetric survey was made using the Autel EVO II RTK Series V3 UAS (Autel, Shenzhen, China) and following the SfM technique for image processing. The TLS point clouds were acquired by means of the Riegl VZ-400i laser scanner (Riegl, Horn, Austria), and the HMLS data of the study area were collected using the Stonex x120go device (Stonex, Milan, Italy). A global 3D point cloud was extracted from each acquired dataset. Co-registration and validation were performed using common GCPs measured with both the GNSS NRTK and total station approaches. The Leica Viva GS 16 GNSS NRTK receiver (Leica Geosystems, part of Hexagon, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) was also used in kinematic mode, with the antenna mounted on a backpack to acquire 3D points by walking in the study area. Subsequently, the georeferenced and validated 3D point clouds were compared with each other for accuracy evaluation and performance analysis of the different techniques (

Figure 2).

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the study area, the collected data using GNSS NRTK and total station measurements, UAS-based imagery, TLS and HMLS surveys, data processing, georeferencing, validation, and comparison strategies.

Section 3 provides the results, and

Section 4 discusses them, with a focus on the comparison between the different 3D point clouds to evaluate the accuracy and performance of the different methods. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the paper and provides some conclusions.

3. Results

3.1. GNSS NRTK Data and Total Station Results

The GNSS NRTK survey allowed us to obtain the coordinates of the measured points in real time, without a post-processing phase. The 16 GCPs used for georeferencing and validation of the point clouds extracted with the different techniques were surveyed by means of both the GNSS NRTK approach (using corrections from the Veneto Region NRTK network) and the total station, based on two reference points for stationing and orientation (EPSG: 7795—RDN2008/Zone 12 reference system). In

Table 1, we report, for each GCP, the differences between the coordinates measured with the total station and with the GNSS NRTK approach along the east, north, and up axes.

Table 1 shows differences between coordinates up to 12.2 cm along the north axis, with six GCPs that provided horizontal differences greater than 10 cm. Conversely, the differences in elevation were lower than 3.3 cm for all the GCPs.

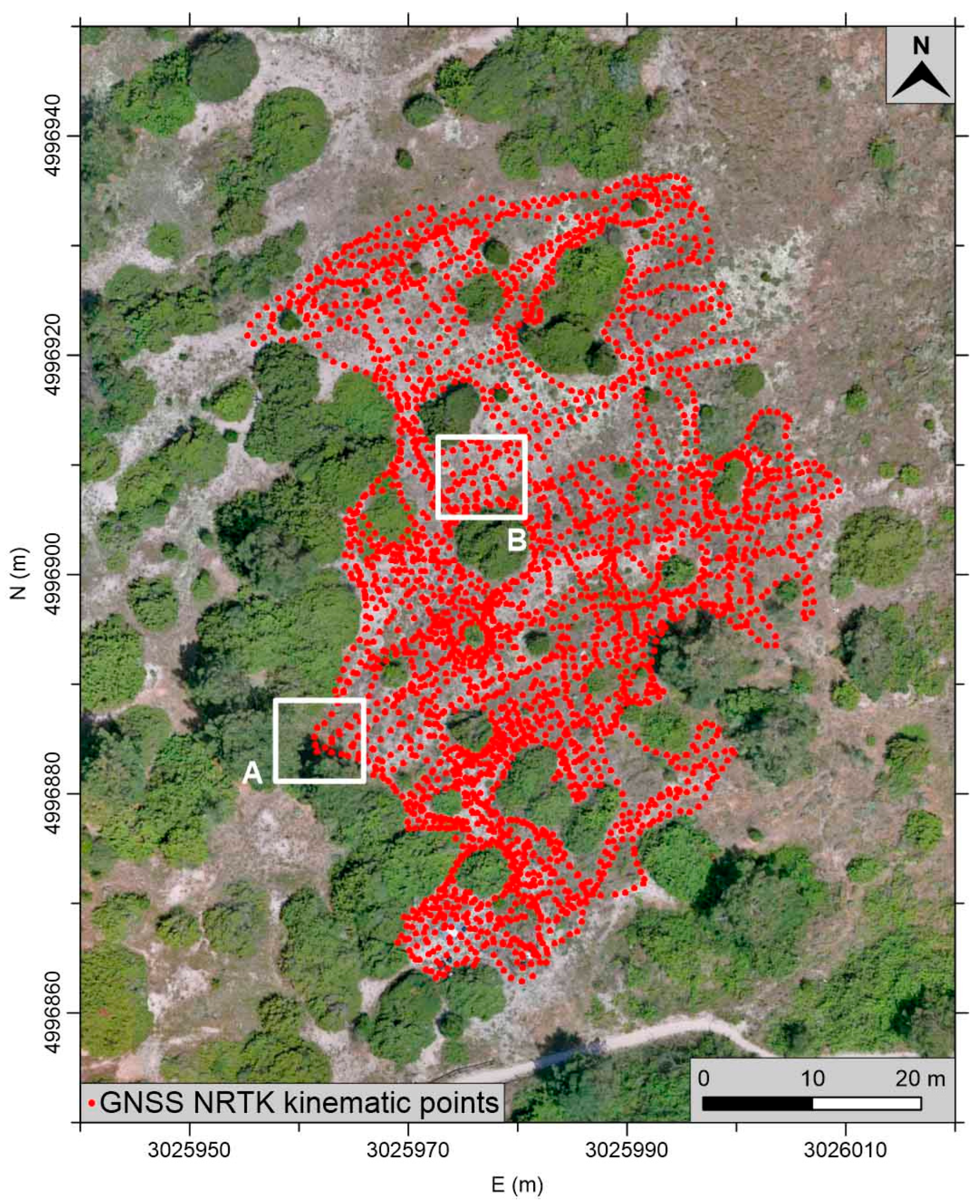

The distribution of the 3D kinematic GNSS NRTK points, registered by the operator who walked through the study area with the GNSS antenna mounted on a backpack, is shown in

Figure 5. The paths are composed of 3D points measured with a mean distance of 0.9 m (sampling rate of 1 s). Note that very dense vegetated areas were uncovered by the GNSS NRTK survey.

3.2. SfM Photogrammetric 3D Point Cloud

The UAS-based images were processed using the SfM technique by means of the Agisoft Metashape software, version 1.8.4. In the alignment phase, a sparse point cloud of the acquired area was obtained using GCPs in the bundle block adjustment during camera orientation. Subsequently, ChPs, not introduced in the processing, were used to validate the 3D model. Two sets of GCP coordinates, obtained both with the GNSS NRTK and total station instruments, were used in the processing in order to evaluate the influence and reliability of the real-time GNSS NRTK approach in georeferencing and validating the SfM 3D model (

Table 2).

Similar values were provided by other researchers who applied the UAS-based photogrammetric SfM technique with GCPs measured using the GNSS approach in contexts comparable to the one under investigation [

22,

37,

51,

52]. Based on the results in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the GCPs and ChPs obtained from the total station measurements were used for the georeferencing and validation of all the point clouds analyzed in this work. Finally, a dense cloud and a corresponding orthophoto were generated (

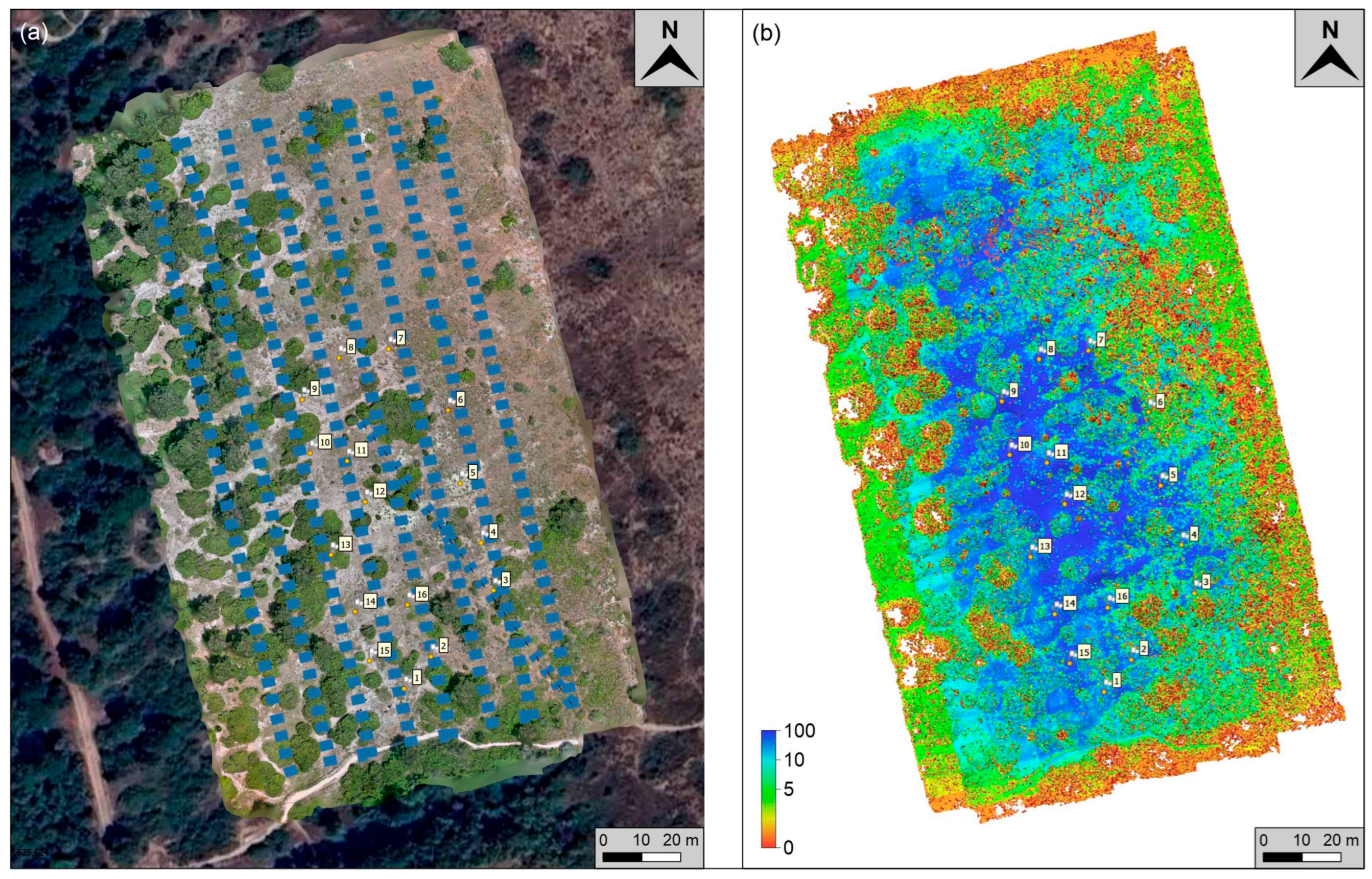

Figure 6a).

The reliability of the extracted 3D points was highlighted by the calculation of the confidence value for each point (point confidence calculation in the Agisoft Metashape software). The value represents the number of combined contributing depth maps used to calculate the position for each specific point.

The map obtained provided the distribution of the confidence parameter (

Figure 6b), which ranged from 0 (lower quality) to 100 (higher quality). By comparing

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b, low values can be detected at the borders of the studied area due to the lower number of images used in the 3D reconstruction, and in dense vegetation, where it is more difficult to extract the features necessary for SfM. For this reason, the borders were excluded in the subsequent analysis since only the area enclosed by the GCPs (

Figure 6) and limited extended portions were studied in detail. Subsequently, the photogrammetric point cloud was processed by applying the “Split Ground Points” tool of the Leica Cyclone 3DR software, version 2024.1, to remove points that represent vegetation. After some tests and in relation to the characteristics of the surveyed terrain, the filtering parameters were set as follows: maximum slope of the terrain = 18°; direction = Z (elevation); extraction grid size = 0.3 m; extraction strategy = check noisy points. These values were chosen after some attempts, in which a lower value in “maximum slope of the terrain” tends to remove ground points in areas with small depressions or bumps, while higher values were not efficient in vegetation detection and filtering. On the other hand, the choice of 0.3 m as the size of the extraction grid seemed to be the better parameter and less sensitive to small variations in the morphological terrain in the study area. Lastly, the direction was set along the Z-axis due to the predominantly flat nature of the terrain analyzed.

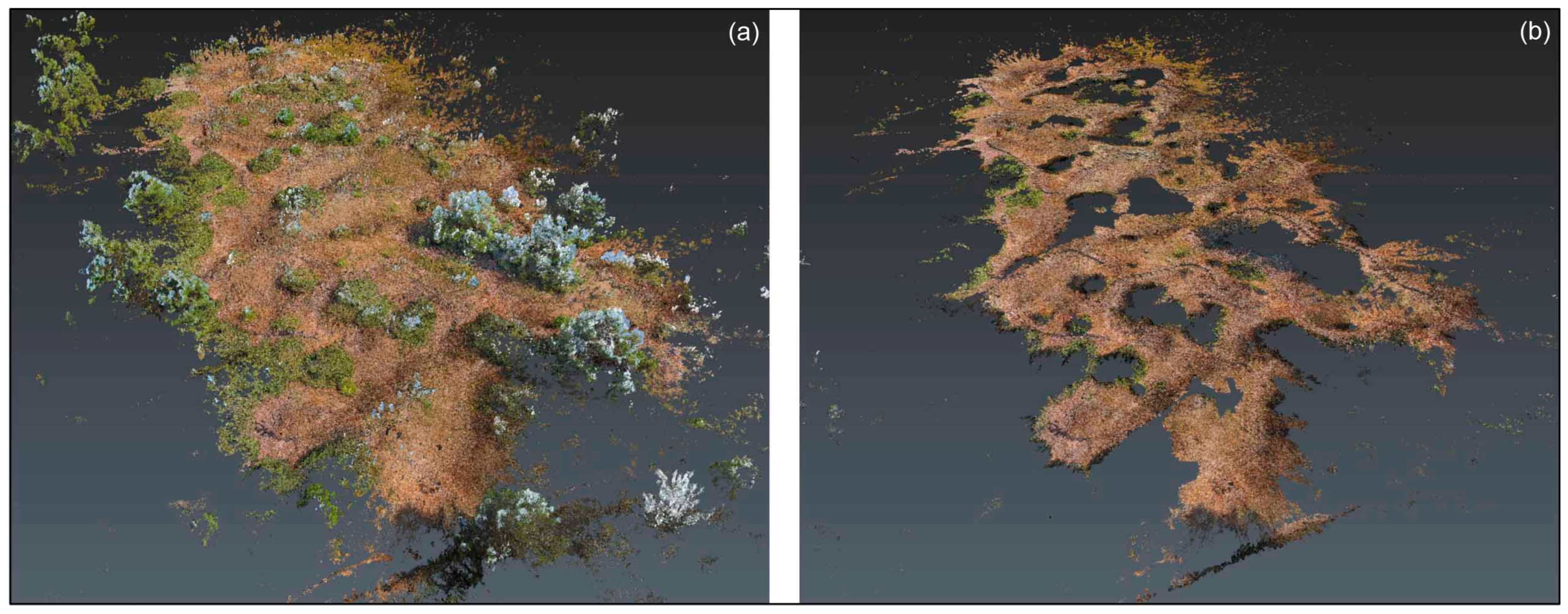

Finally, the initial point cloud of 160 million points was reduced to 29 million after clipping and filtering the vegetation (

Figure 7).

The processing time to extract the products of the survey from the photogrammetric images was in the order of 2 days (depending on many factors, including the computational capabilities), requiring an expert operator.

3.3. TLS Point Clouds Processing

The eight scans acquired with the Riegl VZ-400i TLS instrument were processed using the RiSCAN Pro software (v. 2.11). The Automatic Registration 2 tool was applied. First, the selection of the scenario determined the Voxel dimensions for the registration phase: the “outdoor—non-urban” scenario (considering the environment of this case study) was established, with a Voxel size of 0.5 m. The Voxel count parameter was set at a value of 1024 and indicates how many Voxels are used in the X, Y, and Z directions during the registration process. Applying the MSA tool, the process came to a standard deviation error, calculated on the 8079 plane patches used, of 6 mm.

In the subsequent georeferencing phase, the mean error in the GCPs was 4 mm, while the error in the ChPs was 5.5 mm. This result was significantly better than that provided by Guisado-Pintado et al. [

24], who obtained an alignment accuracy for TLS point clouds with mean target distance errors of 4 mm and 3.5 cm using GCPs, probably due to the fact that they used GCPs measured with the GNSS RTK technique.

The filtering of the point clouds was performed in two steps. The first filter was applied during the scan import phase, deleting the points outside a range of reflectance values (from −25 to +5 dB). The second editing came with the “Split Ground Points” filter tool of the Cyclone 3DR software, as was performed for the photogrammetric data.

The final point cloud, after the first filtering, was made up of 123 million points, reduced to 35 million after clipping and vegetation filtering (

Figure 8).

The total processing time of the TLS data was in the order of 1 day (again, depending on many factors, including the computational capabilities), requiring an expert operator.

3.4. HMLS 3D Processing

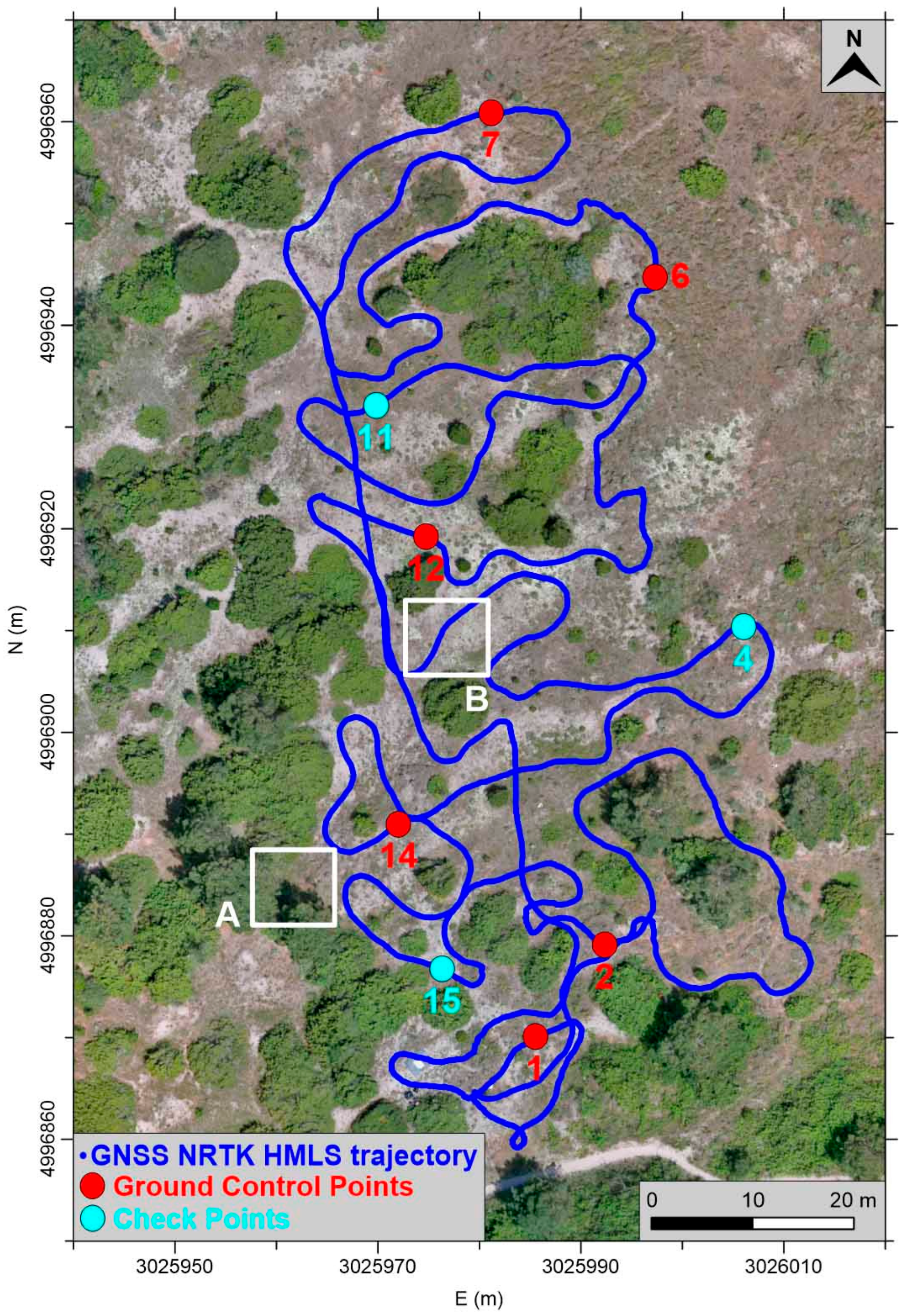

Data acquired with the HMLS Stonex x120go device were processed using the Stonex GOpost software, version 2.3.0.0.

The HLMS processing allowed for the reconstruction of the point cloud and the odometry data, that is, the trajectory of the operator during the acquisition. Subsequently, the global point cloud was georeferenced using the coordinates of the six acquired GCPs (numbers 1, 2, 6, 7, 12, and 14,

Figure 9), while the other three measured ground points were used as ChPs (numbers 4, 11, and 15,

Figure 9). The comparison between the coordinates measured with the total station and those obtained from the model, after the registration phase, provided mean distances of 0.063 m and 0.076 m and standard deviations of 0.114 m and 0.139 m for GCPs and ChPs, respectively. These values are more than acceptable since Sofonia et al. [

35], in a similar environment, provided differences in HMLS data based on GCPs measured with the GNSS NRTK technique of 0.05 ± 0.31 m, even if the sensor was mounted on a UAS.

The resulting point cloud contained about 95 million points, which became 39 million after clipping and vegetation filtering (

Figure 10), while the trajectory consisted of 1579 positions (

Figure 9).

The processing time was in the order of 1.5 days (always depending on many factors, including computational capabilities) with an easy workflow that can be performed by a medium-experienced operator.

3.5. Comparisons Between the 3D Models

The comparisons between the final four point clouds, representing the sand dune system and extracted with aerial- and ground-based techniques, were performed using the M3C2 distance computation plugin of the CloudCompare software, version 2.13.2. The M3C2 algorithm is based on a set of core points, for each of which a distance value and an associated confidence interval are calculated. These core points are typically obtained by subsampling the reference point cloud for an optimized visualization, while the calculation is performed on the original full-resolution dataset (in this processing, the core point subsampling value was 0.01 m). This approach significantly reduces processing time and reflects the fact that results are usually required at a coarser and more uniform spatial resolution (e.g., 1 cm, 5 cm, and 10 cm) than that of high-density scans. Alternatively, full point clouds can be used directly, treating every point as a core point [

49].

The parameters required for the computation include the “normal scale”, the “projection scale”, and the “maximum depth”. The normal scale corresponds to the diameter of the spherical neighborhood defined around each core point for the estimation of the local surface normal (the value used in the processing was 0.25 m). A cylindrical volume, oriented along this normal direction, is then used as the search region to identify corresponding points in the second point cloud. The diameter of this cylinder is defined by the projection scale (the value used in the processing was 0.25 m), while its total height (in both directions along the normal) is controlled by the maximum depth parameter (the value used in the processing was 2.00 m). Larger values for these parameters reduce the influence of local surface roughness; however, they also increase the number of points averaged within each local neighborhood, leading to longer processing times [

49].

In this way, the estimation of precision and performance analysis of the different techniques can be achieved. The georeferenced point clouds obtained by removing the vegetation were used in the processing.

Figure 11 shows the horizontal distribution of the differences resulting from each comparison.

A common color scale of differences for all comparisons, ranging from −0.08 m to 0.30 m (including maximum and minimum values), was used for a better visual representation and a direct quality inspection between the different datasets.

In

Table 3, the results of the comparisons are reported in terms of mean distance and standard deviation.

The mean distances and standard deviation values obtained in the analysis of the differences between the point clouds, ranging from 4.4 to 15.6 cm and from 5.3 to 9.2 cm, respectively, highlight good agreement between the different datasets.

4. Discussion

The kinematic GNSS NRTK technique allowed for the acquisition of 3D points in real time, representing the ground surface. Using this approach, bare ground areas and low vegetation did not pose problems in acquisition, while portions with dense vegetation were not covered due to inaccessibility for the operator (

Figure 5). The UAS-based photogrammetric point cloud, extracted with the SfM technique, provided 3D points with high confidence values in the center of the studied area, where the other datasets were available (

Figure 6). Higher values were obtained on bare ground surfaces and together with the highest density of the acquired images (

Figure 6a). Conversely, the area on the border of the survey, covered with vegetation and in conjunction with low image density, provided the lowest confidence values (

Figure 6b). In any case, as expected, the points in the vegetation have a lower reliability than those in the bare sand dune. On the basis of this result and for a more robust comparison between the different point clouds, vegetation was removed using the Split Ground Points filtering of the Leica Cyclone 3DR software. This procedure was applied to the photogrammetric SfM (

Figure 7), Riegl TLS (

Figure 8), and HMLS (

Figure 10) point clouds. In this way, the comparisons between the different datasets were performed using 3D points referring to the ground surfaces. The rare but possible presence of vegetated portions is due to the non-total efficiency of the filtering algorithm in some specific point distributions, in which a different parameter setting would have caused excessive data removal.

The comparisons between final point clouds, using the version in which vegetation was removed, were made using the M3C2 distance plugin of the CloudCompare software (

Figure 11).

Table 3 shows the results obtained in terms of mean distance and standard deviation between the different 3D models. Analyzing the standard deviation values, the best result was provided by the comparison between the UAS SfM and GNSS NRTK kinematic measurements (5.34 cm), with a value in agreement with that provided by Duo et al. [

51] using UAS-based SfM photogrammetry and GNSS data to analyze artificially scraped dunes in Porto Garibaldi (Comacchio, Italy). From

Table 3, the mean distance was greater than the standard deviation (6.00 cm), as expected, since GNSS NRTK acquired bare-ground points, while UAS-based SfM photogrammetry cannot penetrate low vegetation, which was not removed by the Split Ground Points filter algorithm (

Figure 7b, where some low vegetation clumps were not removed). Similar results were obtained by Yurtseven [

45], who compared different datasets acquired with UAV (using different flight altitudes and SfM technique) and GNSS NRTK measurements in a valley of bare-earth near Istanbul (Turkey). The authors provided a standard deviation for the differences from 5.7 cm to 7.1 cm.

Figure 11c shows some positive differences (in the order of 25–28 cm, areas C, D, E, and F) detected close to the removed/unremoved dense vegetation (border effects,

Figure 5), highlighting the non-optimal performance of the Split Ground Points filter algorithm.

However, the highest standard deviation was obtained in the comparison between the HMLS and UAS SfM data (9.23 cm). Again, the border effects are evident in

Figure 11b, where positive values of the mean distance (up to 30 cm) are related to surfaces with unremoved vegetation (area A in

Figure 5 and

Figure 11b, as an example). Note that HMLS (terrestrial-based) and UAS-based (aerial-based) SfM techniques collect 3D points with different approaches. For this reason, the sparse/dense vegetation was acquired with points of view that were hardly comparable, as from aerial- and ground-based techniques, the level of penetration of the vegetation can be very different. In this way, the application of the Split Ground Points filter algorithm to remove the vegetation can provide significant differences and/or non-optimal results for vegetation acquired from very different points of view. The described difficulties in the comparison between aerial- and ground-based datasets can be extended in the TLS–UAS SfM analysis of the differences since the standard deviation was 8.07 cm, in the same order as that obtained by Seymour et al. [

22] (value of 7.2 cm), who compared the TLS point cloud with UAS DSM in a vegetated dune. The standard deviation value reported in

Table 3, together with the calculated mean distance (4.44 cm, the lowest value), highlights slightly better TLS performance than HMLS (see also the values related to the HMLS–UAS SfM comparison). However, the HMLS-based and TLS point clouds provided comparable data with differences on the order of a few centimeters (

Table 3). The comparison between the TLS point cloud and the GNSS NRTK 3D points reflects the above considerations. The standard deviation of differences (7.27 cm) was in the same order as those provided by Mancini et al. [

27] (RMS of 11 cm), who studied a beach dune system in Marina di Ravenna (Italy), and Kovanic et al. [

7] (standard deviation of 6.8 cm), who applied the two techniques to a non-vegetated area in eastern Slovakia.

In terms of mean distance between the compared point clouds, the highest values were obtained when HMLS was involved (

Table 3). In detail, the acquisition approach of the HMLS device produced a point cloud that does not allow for an easy removal of points in vegetated areas with the Split Ground Points filter algorithm, as highlighted in area A of

Figure 11b or

Figure 11e,f. Taking into account the portions with bare ground/low vegetation (area B of

Figure 5 and

Figure 11 as an example), the comparisons between the HMLS data with the UAS SfM, GNSS NRTK, and TLS point clouds provided mean distances with positive values. Consequently, this technique allowed us to always acquire a point cloud above the vegetation, even the lowest, with a very low penetration ability (

Figure 11e), and, in general, it has produced 3D data with higher elevations. In contrast, the 3D GNSS NRTK kinematic points provided the best representation of the surface of the bare sand dune since they were characterized by the lowest elevation, in agreement with the results obtained by Guisado-Pintado et al. [

24]. However, the GNSS NRTK technique provided a density for the 3D points that was not comparable to that of the point clouds obtained with the other techniques (

Table 4).

Based on the results obtained in this work, some advantages and disadvantages can be highlighted for the different techniques. The GNSS NRTK approach provides the best results for the survey of the ground surface since the acquired points are below the vegetation; moreover, the acquisitions are performed rapidly and without a post-processing phase because the 3D coordinates of the points are directly available. The limitations of this technique are related to resolution (low) and accuracy, on the order of some centimeters. UAS-based photogrammetric surveys allow us to obtain photorealistic information; with a post-processing phase, high-resolution 3D points can be extracted, and an orthophoto of the study area can be generated. In addition, the technique provides a good representation of flat areas, while results obtained on steep slopes and medium/dense vegetated areas can be inaccurate in many cases. The TLS approach provides the best solution in terms of the final accuracy and resolution of the measured points. However, the limitation of acquisition stationing can produce significant shadow zones, especially with complex morphology and significant vegetation coverage of the analyzed areas. HMLS, even with lower accuracies and resolutions compared with UAS-based photogrammetry and TLS approaches, can provide high coverage of the study area due to the flexibility of the handheld acquisition. In this way, this technique represents the best solution to reduce shadow zones in complex morphology (including steep slopes) and with a reduced time to perform surveys on the ground.

Moreover, due to the limitations highlighted in this work by the “Split Ground Points” filter algorithm in removing vegetation using different datasets, from different sensors and platforms, in future developments, new surveys using UAS-based ALS instruments with multiple returns will be planned. In this way, tests will be performed to estimate the efficiency of the ALS last return in vegetation penetration during acquisitions compared to approaches based on the post-processing of the data.

5. Conclusions

In this work, GNSS NRTK, UAS-based SfM photogrammetry, ground-based TLS, and HMLS techniques were tested for the 3D survey of complex coastal environments such as the vegetated sand dune system of the Caleri area in the Po River Delta (Italy).

GNSS measurements, using the NRTK approach, were performed to acquire 3D points in kinematic mode (the GNSS antenna was fixed on the backpack of an operator who walked throughout the area of investigation), and the coordinates of GCPs were used to georeference point clouds obtained with the other techniques. A second measurement of the GCPs was carried out by means of a total station to evaluate the accuracy of the GNSS NRTK technique. The results suggested the use of GCPs measured with the total station to georeference point clouds.

The UAS-based SfM photogrammetric technique allowed us to extract a dense point cloud of the study area in dense, sparse/low vegetated areas and bare-ground surfaces. Based on point confidence filtering in the Agisoft Metashape software, reliable data were obtained on unvegetated/low vegetated areas; for this reason, clusters of dense vegetation were removed from the point cloud using the Split Ground Points filter of the Leica Cy-clone 3DR software.

The ground-based TLS point cloud was obtained by aligning eight static scans acquired with the Riegl VZ-400i laser scanner, while the dynamic 3D survey was performed with an HMLS device, following a trajectory designed to maximize coverage. In both cases, GCPs and ChPs were used in the georeferencing and validation phases.

The four point clouds, co-registered in the same reference system, were then compared to evaluate the performance in terms of accuracy, resolution, time of survey, and processing. The results provided point clouds in good agreement with each other since the standard deviations of the differences were lower than 9.3 cm. The best technique for the description of the bare ground surface was GNSS NRTK, but it had a very low spatial resolution. The acquisition time was 51 min without a post-processing phase. Conversely, the HMLS provided a point cloud with the highest elevation value for the 3D points, including the low and sparse vegetation areas, but with high data resolution. The survey required 20 min, and the post-processing was performed in about a working day. Using UAS-based SfM photogrammetry and ground-based TLS techniques, similar results were obtained since the mean distance of the differences between the point clouds was 4.44 cm. More significant differences were obtained close to the removed/unremoved dense vegetation, highlighting that split ground filtering works with different efficiency if considering data from aerial- or ground-based acquisitions. The measurement and processing time for these techniques were 11 min and two working days for the UAS-based point cloud and 1 h and 20 min and one working day for the TLS-based data, respectively. On the basis of these results, UAS-based and TLS-based point clouds provided similar performance on the investigated sand dune area.

Finally, when high accuracy is not a crucial requirement, the flexibility provided by real-time tracking, ease of use, post-processing without the need for highly specialized operators, and competitive acquisition and processing times make HMLS a powerful tool for acquiring useful 3D data in complex natural environments, such as the vegetated sand dunes area investigated in this work.