Structural-Functional Suitability Assessment of Yangtze River Waterfront in the Yichang Section: A Three-Zone Spatial and POI-Based Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Shoreline Suitability from the Human–Land Relationship Perspective

2.2. Multifunctional Compression of Shoreline Space

2.3. Constraint–Suitability Logic and Indicator Mapping

3. Materials and Methods

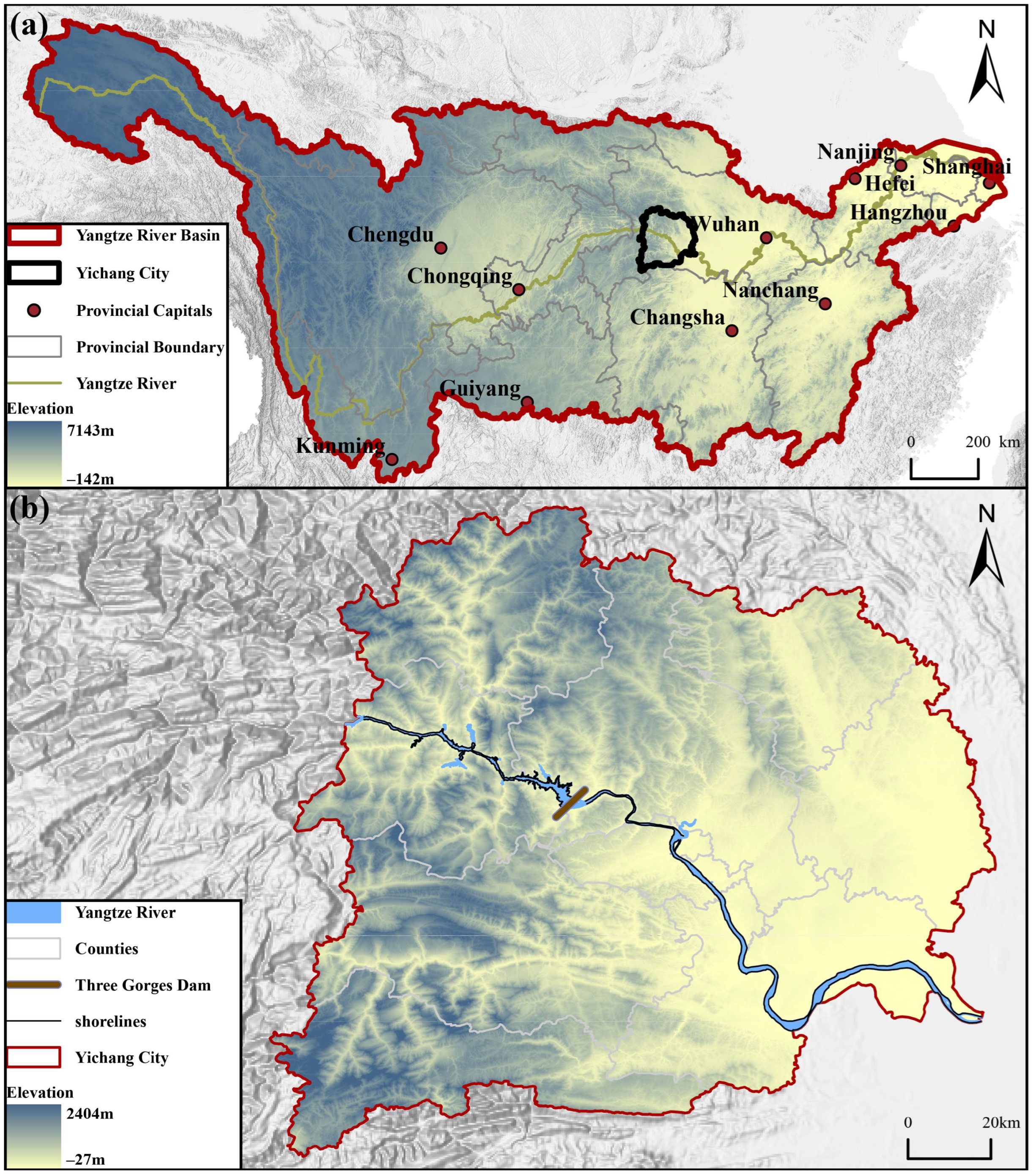

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Methods

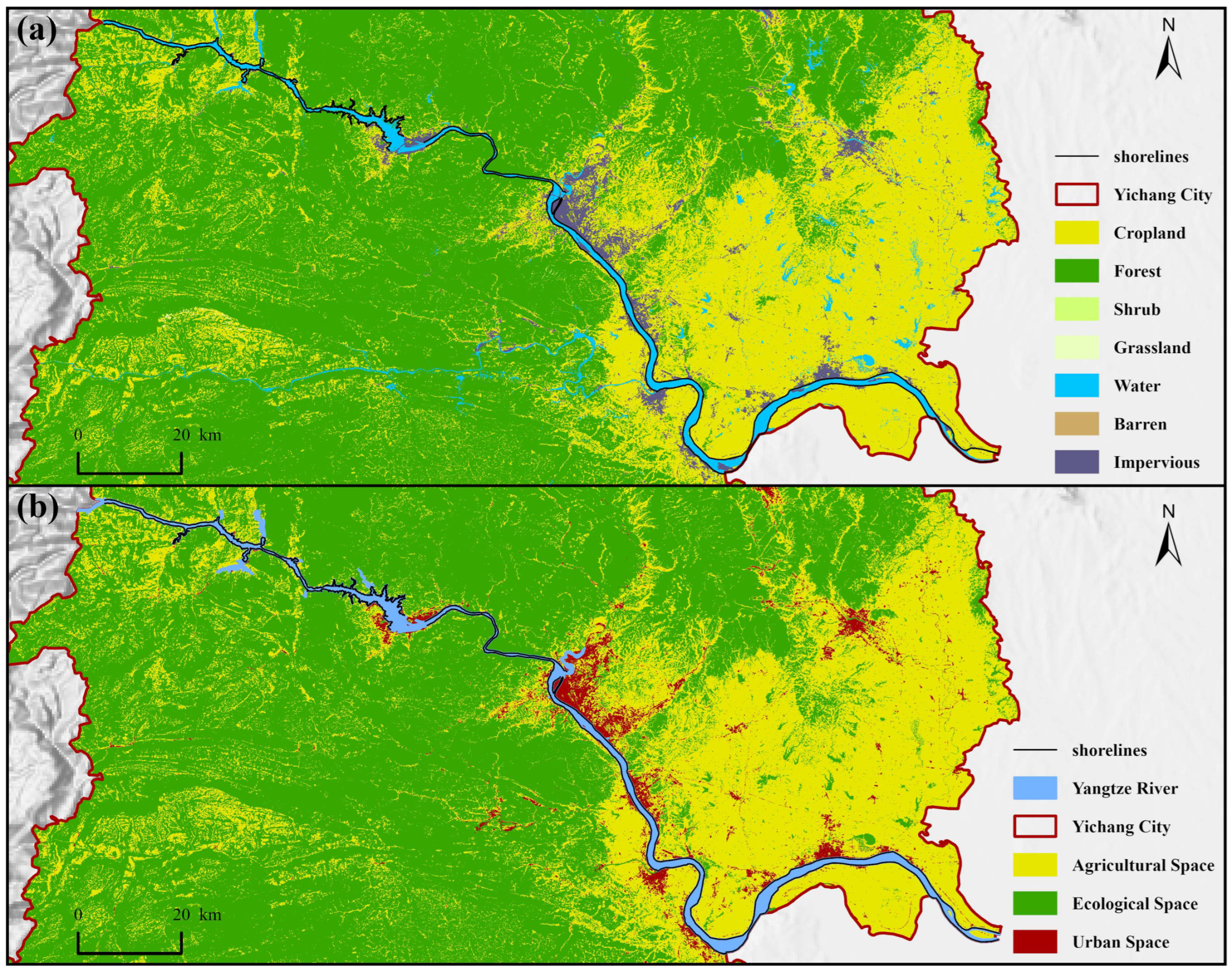

3.3.1. Dividing Dominant Functions of Shorelines Based on Three-Zone Space

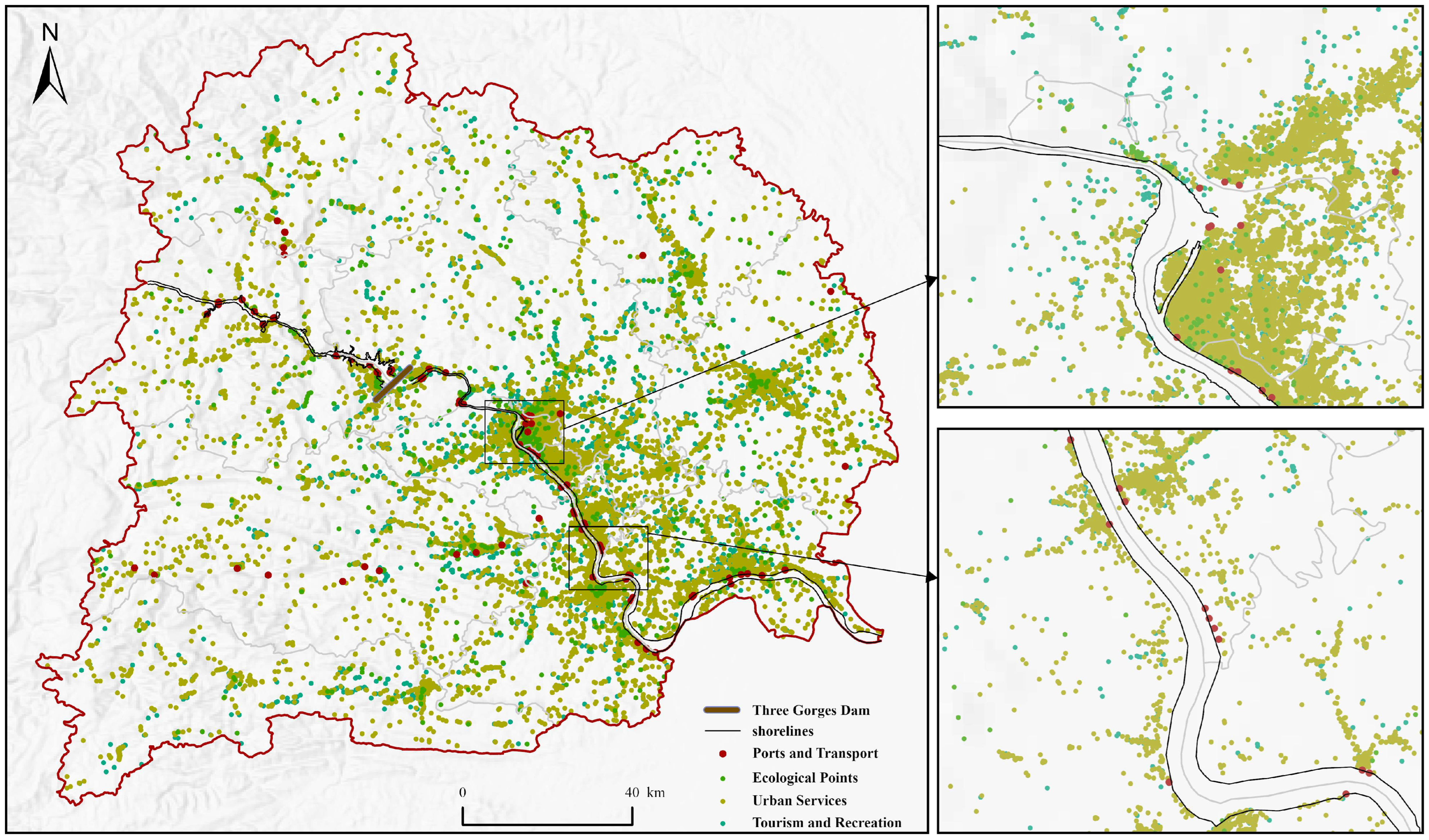

3.3.2. Refining Shoreline Functions by Integrating POI Data

3.3.3. Indicator Standardization and Weight Assignment

4. Results

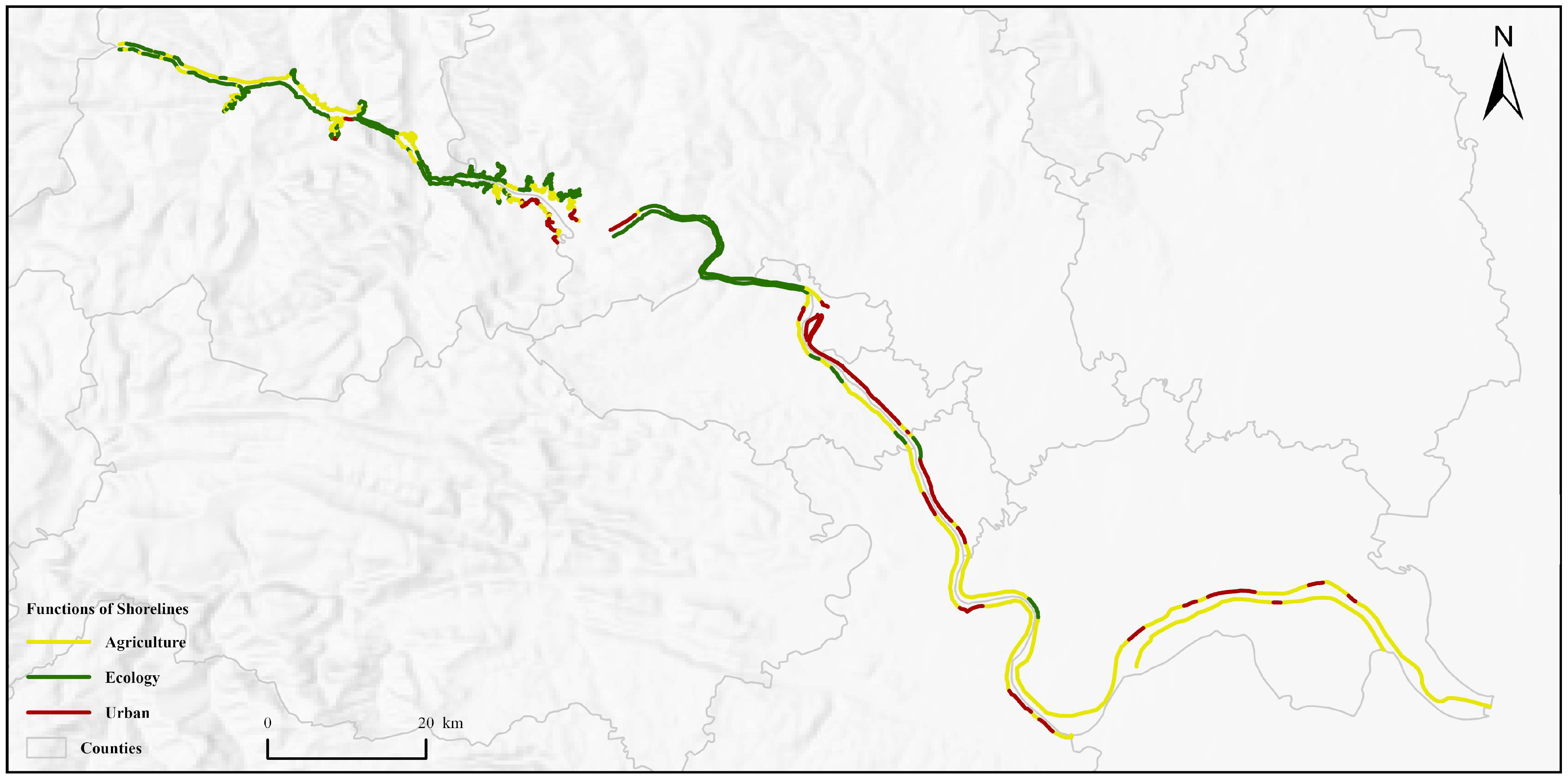

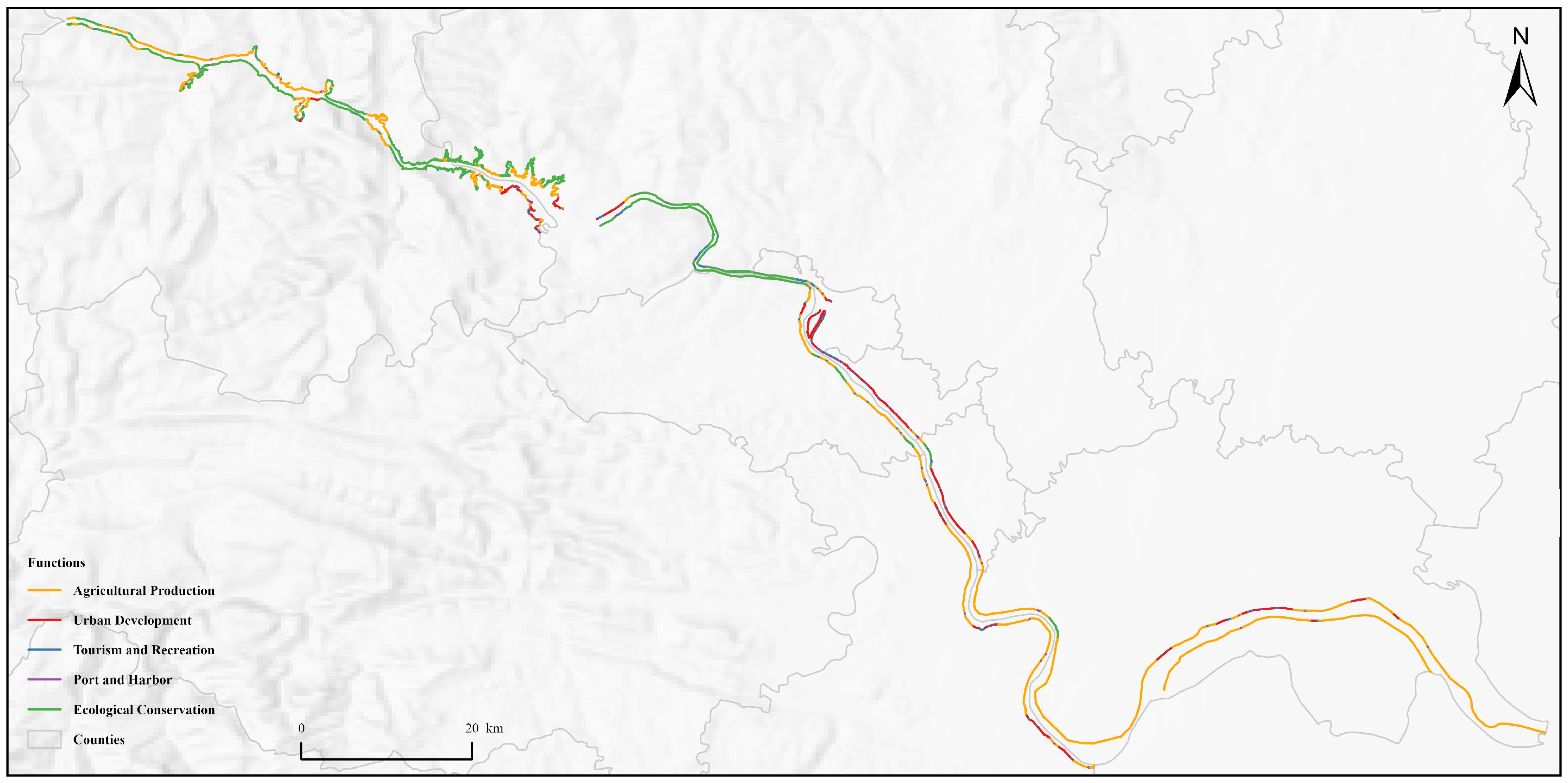

4.1. Classification of Shoreline Dominant Functions Based on “Three-Zone Space”

4.2. Refinement of Shoreline Functions Based on POI Data Integration

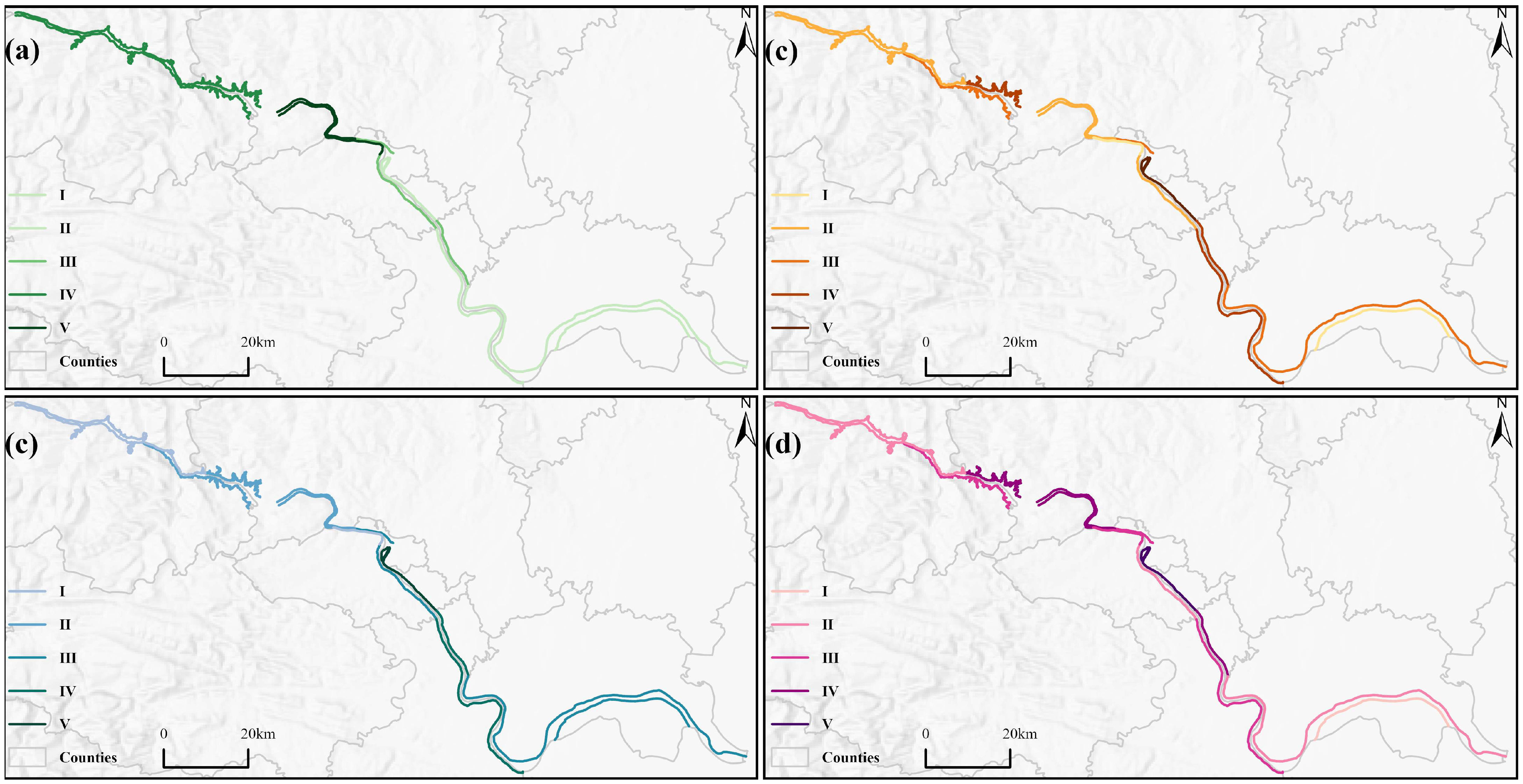

4.3. Comprehensive Evaluation Results of Shoreline Utilization Suitability

5. Discussion

5.1. Functional Zoning of Shorelines Based on the “Three-Zone Space” Classification

5.2. Enhanced Identification of Shoreline Functions Through POI Data Integration

5.3. Decision Value and Practical Implications of the Suitability Evaluation

5.3.1. Spatial Patterns and the Significance of Weight Allocation

5.3.2. The Agriculture-Suitability Mismatch: Unpacking Systemic Inertia

5.4. Differentiated Management Strategies

- (1)

- For high-suitability units with concentrated urban/port functions, these areas represent zones of alignment between high development potential and current intensive use. Management should focus on qualitative intensification and ecological modernization within this high-potential envelope, rather than spatial expansion. First, implementing smart logistics to reduce congestion and pollution, and mandating shoreline ecological restoration projects within port boundaries to mitigate local environmental impacts. Second, strategic urban waterfront regeneration. Rejuvenating underutilized or obsolete urban shoreline parcels (identified through fine-grained POI analysis) for mixed-use development that integrates public access, green space, and climate-adaptive design, thereby enhancing value without spatial expansion.

- (2)

- For low-suitability, high-constraint units. Characterized by an accumulation of ecological sensitivities and high geohazard risks, policy must enforce absolute protection and proactive risk governance. First, enforcing ecological red lines with monitoring. Legally formalizing the boundaries of low-suitability ecological zones (as per evaluation results) and establishing real-time geohazard monitoring and early-warning systems. Furthermore, developing compensated stewardship programs. Creating payment for ecosystem services (PES) schemes or other fiscal mechanisms to support communities in these areas for maintaining protective land uses, rather than high-risk economic activities.

- (3)

- For agricultural production shorelines with moderate-low suitability. Management must address the systemic inertia revealed by the spatial mismatch. Strategy should pivot from supporting general production to facilitating a structured, risk-informed transition. First, implementing differentiated agricultural zoning. Subdividing agricultural zones based on micro-scale suitability scores to promote climate-resilient and precision agriculture in stable areas, while guiding the conversion of highest-risk marginal farmland (e.g., units with very low scores in flood-prone areas) to constructed wetlands or riparian buffers, supported by targeted ecological compensation. Moreover, fostering alternative livelihoods. Supporting the development of agri-ecology, eco-tourism, or non-farm industries in communities within mismatch zones to reduce dependency on vulnerable agricultural systems.

- (4)

- For tourism and recreation shorelines within ecological settings, given their symbiotic yet potentially impactful relationship with ecological conservation areas, management must ensure that tourism development remains within the ecological carrying capacity. First, implementing carrying capacity-based management. Setting and enforcing strict visitor caps for scenic nodes within ecological shorelines to prevent ecosystem damage. In addition, promoting community-integrated ecotourism. Developing tourism models where local communities are the primary beneficiaries and custodians, ensuring economic incentives are aligned with long-term conservation of the landscape and cultural heritage.

5.5. Research Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Fang, Z. Spatial Pattern Change and Influencing Factors of Industrial Eco-Efficiency of Yangtze River Economic Belt (Yreb). SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221113849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Petrosillo, I.; Li, C. Effects of Changing Riparian Topography on the Decline of Ecological Indicators Along the Drawdown Zones of Long Rivers in China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1293330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.-J.; Hui, Z.O.U.; Chen, W.-X.; Min, M.I.N. The Concept, Assessment and Control Zoning Theory and Method of Waterfront Resources: Taking the Resources Along the Yangtze River as an Example. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 2209–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tang, D.; Kong, H.; Boamah, V. Impact of Industrial Structure Upgrading on Green Total Factor Productivity in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Kong, X.; Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Zhu, Y. Spatially Explicit Evaluation and Driving Factor Identification of Land Use Conflict in Yangtze River Economic Belt. Land 2021, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, C. Quantitative Evaluation of Eco-Environmental Protection Policy in the Yangtze River Economic Belt: A Pmc-Index Model Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xu, X. Foundation and Strategy of Well Coordinated Environmental Foundation and Strategy of Well-Coordinated Environmental Conservation and Avoiding Excessive Development in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. (Chin. Version) 2020, 35, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Ye, Y. Resilient Strategies for Disaster Prevention and Ecological Restoration of River and Lake Benggang and Bank Erosion. Water 2025, 17, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Pu, L.; Huang, S. Simulation of Coastal Resource and Environmental Carrying Capacity in the Yangtze River Delta Coastal Zone Based on Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1008231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liu, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Hong, D. Vegetation Land Segmentation with Multi-Modal and Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Images: A Temporal Learning Approach and a New Dataset. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indifrag V2.1: An Object-Based Fragmentation Analysis Software Tool; 2017; Available online: https://www.cgat.webs.upv.es/BigFiles/indifrag/IndiFrag_BriefUserGuide_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Boryan, C.; Craig, M.E. Multiresolution Landsat Tm and Awifs Sensor Assessment for Crop Area Estimation in Nebraska. Proc. Pecora 2005, 16, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Shi, W.; Atkinson, P.M. Sub-Pixel Mapping of Remote Sensing Images Based on Radial Basis Function Interpolation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, P.; Tan, K.; Cheng, L. Sub-Pixel Change Detection for Urban Land-Cover Analysis Via Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Images. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, 17, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Urban Functional Area Identification Based on Poi Data. Acad. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2023, 2, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ma, X.A. A Spatial Semantic Feature Extraction Method for Urban Functional Zones Based on Pois. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Chen, F.; Zhou, G. Functions of Village Classification Based on Poi Data and Social Practice in Rural Revitalization. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, P.; Wang, D.; Meng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhai, W. Recognizing Urban Functional Zones by Gf-7 Satellite Stereo Imagery and Poi Data. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Qin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chuai, X. Study on the Optimization of Territory Spatial “Urban–Agricultural–Ecological” Pattern Based on the Improvement of “Production–Living–Ecological” Function under Carbon Constraint. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, J.; Ou, D.; Fei, J.; Gong, S.; Xiang, Y. Optimal Allocation of Territorial Space in the Minjiang River Basin Based on a Double Optimization Simulation Model. Land 2023, 12, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Xu, S.; Du, M.; Li, S. Urban Functional Zone Identification by Considering the Heterogeneous Distribution of Points of Interests. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 5, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Guo, G. Study on the Effectiveness of Navigation Safety Measures for Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge. MATEC Web Conf. 2020, 308, 03004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Ye, J.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y. Urban Functional Zone Classification Based on Poi Data and Machine Learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Nie, R. Experimental Study of the Effects of Riverbank Vegetation Conditions on Riverbank Erosion Processes. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2023, 23, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ren, C. Green Development Evaluation and Problem Areas Identification of the Yangtze River Economic Belt from the Perspective of Major Function Oriented Zones. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 2569–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Yao, S.; Shan, M.; Guo, C. Case Study: Influence of Three Gorges Reservoir Impoundment on Hydrological Regime of the Acipenser Sinensis Spawning Ground, Yangtze River, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 624447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yin, S.; Wang, S.; Han, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, M. The Theory of Regional Function Identification of Coastal Territorial Space under the Shaping of the Flowing Space. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Huang, Z.; Xu, J. Assessment on Suitability of Scenic Spots Location Inthe Yangtze River Delta. J. Nat. Resour. 2013, 28, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Wei, W.; Yin, L.; Zhou, J. Spatial-Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Mechanism Analysis of Urban Space in China’s Three-River-Source Region: A Land Classification Governance Framework Based on “Three Zone Space”. Land 2023, 12, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Xue, W.; Yuan, B.; Li, T.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Cui, Y.; Xu, W.; Wei, X.; et al. A comprehensive assessment framework for water ecological space health based on remote sensing technology. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2025, 29, 689–699. [Google Scholar]

- Yelistratova, L.; Apostolov, A.; Khodorovskyi, A.; Khyzhniak, A.V.; Tomchenko, O.V.; Lialko, V.I. Use of Satellite Information for Evaluation of Socio-Economic Consequences of the War in Ukraine. Ukr. Geogr. J. 2022, 2022, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, X. A Novel Method for Identifying the Boundary of Urban Built-Upareas with Poi Data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2016, 71, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimov, S.; Martynov, S.; Kunitskyi, S.; Kupchyk, L. Risk and Hazard Analysis of Riverbank Filtration Water Intakes for Water Safety Planning. In Modeling, Control and Information Technologies: Proceedings of VIII International Scientific and Practical Conference; National University of Water and Environmental Engineering: Rivne, Ukraine, 2025; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Lato, M.; Quinn, P.; Whittall, J. Challenges with use of Risk Matrices for Geohazard Risk Management for Resource Development Projects. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Mining Geomechanical Risk, Perth, Australia, 9–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 M Annual Land Cover Dataset and Its Dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Zhao, F.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Török, Á.L. andslide Susceptibility Mapping in Three Gorges Reservoir Area Based on Gis and Boosting Decision Tree Model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 2283–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, N.; Wu, M.; Wu, P.; He, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Fang, S. The Scale Identification Associated with Priority Zone Management of the Yangtze River Estuary. Ambio 2022, 51, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, F.; Zhou, C. Identification of Urban Functional Zones Based on Poi Density and Marginalized Graph Autoencoder. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Mo, Y.; Wang, W. Identification and Spatio-Temporal Characterization of Urban Functional Areas Based on Poi Data. In Proceedings of the SPIE; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; p. 130642D. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q. A Novel Invariant Based Commutative Encryption and Watermarking Algorithm for Vector Maps. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Wang, D. Evaluation Analysis and Strategy Selection in Urban Flood Resilience Based on Ewm-Topsis Method and Graph Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Exploratory Simplification of Collaborative Evaluation Model Based on Ahp. Oper. Res. Fuzziol. 2023, 13, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabidoche, M.; Vanbrabant, Y.; Brouyère, S.; Stenmans, V.; Meyvis, B.; Goovaerts, T.; Petitclerc, E.; Burlet, C. Spring Water Geochemistry: A Geothermal Exploration Tool in the Rhenohercynian Fold-and-Thrust Belt in Belgium. Geosciences 2021, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Chen, K.; Cheng, J.; Tan, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Q. Ecological Water Quality of the Three Gorges Reservoir and Its Relationship with Land Covers in the Reservoir Area: Implications for Reservoir Management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1196089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X. Evolution Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of the Territorial Space Pattern in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land 2022, 11, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Wang, G.; Lu, Q.; Xiong, C. Function Evaluation and Optimal Strategies of Three Types of Space in Cross-Provincial Areas from the Perspective of High-Quality Development: A Case Study of Yangtze River Delta, China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 2763–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Chen, M.; Tang, Z. A 10-M Scale Chemical Industrial Parks Map Along the Yangtze River in 2021 Based on Machine Learning. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.C.; Yang, Z.P.; Liu, Y.H.; DEStech Publications, Inc. Analysis on Spatial Structure of Tourist Resources of Yellow River Three Gorges Scenic Area in Gansu Province. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Science (ICSS), Changsha, China, 6–8 June 2025; pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, J.; Hong, X.; Liu, J. Study on Comprehensive Evaluation of Protection and Utilization of Artificial Canal in Yichang City. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 794, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, J.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Xie, J.; Liu, Z. Suitability Evaluation of Port Construction Site in Three Gorges Reservoir Based on Hybrid Units. Geol. Surv. China 2019, 6, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-R.; Li, X.-Q.; Yu, X.; Zhao, T.-C.; Ruan, W.-X. Exploring the Ecological Security Evaluation of Water Resources in the Yangtze River Basin under the Background of Ecological Sustainable Development. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Li, L.; Chu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, D. Gis-Based Risk Assessment of Flood Disaster in the Lijiang River Basin. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Li, L.; Yu, H.; Xiong, J.; Yu, J. Considering Human Interference to Prioritize Spatial Conservation in a Transboundary River Basin Using Zonation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Yang, P.; Meng, C.; Zhou, Q.; Tang, H. Model Application of an Agent-Based Model for Simulating Crop Pattern Dynamics at Regional Scale Based on Matlab. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2014, 30, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Chen, S.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Fan, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, L. Management and Control of Agricultural Production Space in the Yanhe River Basin Based on Peasant Household Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; An, Y.; Pan, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Gu, Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, F. Dynamic Transfer and Driving Mechanisms of the Coupling and Coordination of Agricultural Resilience and Rural Land Use Efficiency in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 1589–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, S.; Schreckenberg, K.; Dyke, J.; Schaafsma, M.; Balbi, S. Agent-Based Modelling to Assess Community Food Security and Sustainable Livelihoods. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2018, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y. Analysis of Multiple Paths to Improve Agricultural Land Use Efficiency in the Tarim River Basin. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2025, 33, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion Layer | Attribute | Indicator Layer | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Importance of Ecological Protection | A11 | + | Proportion of Ecological Shoreline | Calculated based on the length of Ecological Conservation shorelines |

| A12 | + | Mean Vegetation Coverage (NDVI) | Calculated from MOD13A3 data | |

| A13 | + | Elevation Variation Coefficient | Calculated from DEM data | |

| B1 Suitability for Production Development | B11 | + | Nighttime Light Intensity | Calculated from PCNL (Pontaneous Composite Nighttime Light) data (https://zenodo.org/records/10989889) (accessed on 1 August 2025) |

| B12 | + | Proportion of Port and Harbor Shoreline | Calculated based on the length of Port and Harbor shorelines | |

| B13 | + | Factory POI Density | Calculated from POI data | |

| B14 | + | Transportation Accessibility | Calculated from OSM data (https://www.openstreetmap.org) (accessed on 1 August 2025) | |

| B15 | + | Shoreline Curvature | Calculated from shoreline geometry | |

| C1 Suitability for Construction Development | C11 | + | Proportion of Urban Leisure Shoreline | Calculated based on the length of Tourism and Recreation shorelines and Urban Development shorelines |

| C12 | + | Population Aggregation Degree | Calculated from GHS-POP data (https://ghsl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/download.php?ds=pop) (accessed on 1 August 2025) | |

| C13 | + | Urban POI Density | Calculated from POI data | |

| C14 | + | GDP per Capita | Calculated from regional statistical yearbook data | |

| C15 | − | Mean Slope | Calculated from DEM data | |

| D1 Constraint of Disaster Risk | D11 | − | Weighted Geohazard Risk Index | Calculated from geohazard point data (www.gisrs.cn) (accessed on 1 August 2025) |

| Bank Lines | Agricultural | Ecological | Urban | Total | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream north banks of TGD | 58.58 | 65.88 | 2.37 | 126.83 | 0.46:0.52:0.02 |

| Upstream south banks of TGD | 32.18 | 59.66 | 10.65 | 102.49 | 0.31:0.58:0.11 |

| Downstream north banks of TGD | 89.24 | 32.61 | 53.78 | 175.62 | 0.51:0.18:0.31 |

| Downstream south banks of TGD | 91.82 | 36.76 | 14.24 | 142.82 | 0.64:0.26:0.10 |

| Shorelines | Ecological Conservation Shorelines | Port and Harbor Shorelines | Tourism and Recreation Shorelines | Urban Development Shorelines | Agricultural Production Shorelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream north banks of TGD | 65.43 (51.59%) | 1.50 (1.19%) | 0.87 (0.68%) | 2.16 (1.71%) | 56.86 (44.83%) |

| Upstream south banks of TGD | 57.96 (56.56%) | 1.90 (1.86%) | 3.01 (2.94%) | 8.72 (8.51%)) | 30.89 (30.14%) |

| Downstream north banks of TGD | 29.45 (16.77%) | 5.53 (3.15%) | 12.00 (6.83%) | 43.00 (24.48%) | 85.64 (48.76%) |

| Downstream south banks of TGD | 33.07 (23.16%) | 3.49 (2.44%) | 6.71 (4.70%) | 11.67 (8.18%) | 87.84 (61.52%) |

| Criterion | AHP Weight | Indicator | Entropy Weight | Combined Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.380 | A11 | 0.067 | 0.191 |

| A12 | 0.017 | 0.049 | ||

| A13 | 0.024 | 0.069 | ||

| B1 | 0.141 | B11 | 0.041 | 0.044 |

| B12 | 0.057 | 0.061 | ||

| B13 | 0.076 | 0.081 | ||

| B14 | 0.066 | 0.070 | ||

| B15 | 0.122 | 0.130 | ||

| C1 | 0.063 | C11 | 0.086 | 0.041 |

| C12 | 0.157 | 0.075 | ||

| C13 | 0.181 | 0.086 | ||

| C14 | 0.055 | 0.026 | ||

| C15 | 0.031 | 0.015 | ||

| D1 | 0.416 | D11 | 0.019 | 0.061 |

| Shorelines | A1 | B1 | C1 | Comprehensive | Ranking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Dianjun District Upstream to Gezhouba Dam Shoreline | 0.271 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.350 | 7 |

| X2 | Gezhouba Dam to Dianjun District Downstream Shoreline | 0.111 | 0.060 | 0.024 | 0.249 | 12 |

| X3 | Gezhouba Dam to Xiling District Downstream Shoreline | 0.008 | 0.186 | 0.222 | 0.477 | 1 |

| X4 | Three Gorges Dam to Yiling District North Bank Downstream Shoreline | 0.287 | 0.056 | 0.016 | 0.404 | 5 |

| X5 | Wujiagang District Shoreline Segment | 0.024 | 0.205 | 0.166 | 0.456 | 2 |

| X6 | Xiling District Upstream to Gezhouba Dam Shoreline | 0.125 | 0.105 | 0.037 | 0.319 | 9 |

| X7 | Xiaoting District Shoreline Segment | 0.130 | 0.157 | 0.064 | 0.413 | 4 |

| X8 | Yiling District South Bank Shoreline | 0.298 | 0.057 | 0.015 | 0.426 | 3 |

| X9 | Yiling District Upstream to Three Gorges Dam North Bank Shoreline | 0.194 | 0.145 | 0.016 | 0.390 | 6 |

| X10 | Yidu City Section Shoreline | 0.051 | 0.163 | 0.049 | 0.320 | 8 |

| X11 | Zhijiang City North Bank Section Shoreline | 0.079 | 0.074 | 0.031 | 0.246 | 13 |

| X12 | Zhijiang City South Bank Section Shoreline | 0.027 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.138 | 15 |

| X13 | Zigui County Upstream Section North Bank Shoreline | 0.189 | 0.043 | 0.002 | 0.236 | 14 |

| X14 | Zigui County Upstream Section South Bank Shoreline | 0.214 | 0.040 | 0.007 | 0.261 | 11 |

| X15 | Zigui County Downstream Section South Bank Shoreline | 0.171 | 0.078 | 0.014 | 0.297 | 10 |

| Grade | Grade Characteristics |

|---|---|

| I | Poor |

| II | Fair |

| III | Moderate |

| IV | Good |

| V | Excellent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Qiu, F.; Li, K.; Jia, Y.; Xia, J.; Aishanjian, J. Structural-Functional Suitability Assessment of Yangtze River Waterfront in the Yichang Section: A Three-Zone Spatial and POI-Based Approach. Land 2026, 15, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010091

Li X, Qiu F, Li K, Jia Y, Xia J, Aishanjian J. Structural-Functional Suitability Assessment of Yangtze River Waterfront in the Yichang Section: A Three-Zone Spatial and POI-Based Approach. Land. 2026; 15(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010091

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaofen, Fan Qiu, Kai Li, Yichen Jia, Junnan Xia, and Jiawuhaier Aishanjian. 2026. "Structural-Functional Suitability Assessment of Yangtze River Waterfront in the Yichang Section: A Three-Zone Spatial and POI-Based Approach" Land 15, no. 1: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010091

APA StyleLi, X., Qiu, F., Li, K., Jia, Y., Xia, J., & Aishanjian, J. (2026). Structural-Functional Suitability Assessment of Yangtze River Waterfront in the Yichang Section: A Three-Zone Spatial and POI-Based Approach. Land, 15(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010091