Fine-Grained Classification of Lakeshore Wetland–Cropland Mosaics via Multimodal RS Data Fusion and Weakly Supervised Learning: A Case Study of Bosten Lake, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Dataset Sources

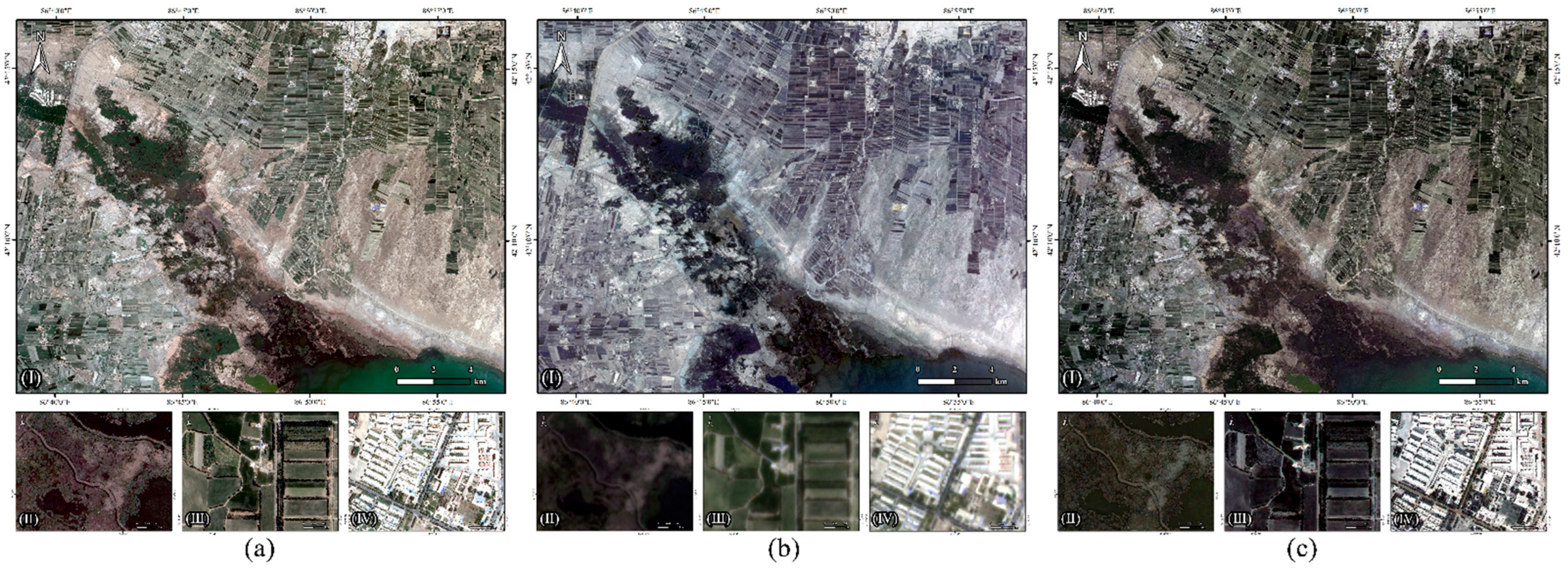

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Multimodal Remote Sensing Data Sources

2.3. Data Preparation and Pre-Processing

2.3.1. Field Survey and Sample Labeling

2.3.2. Data Augmentation Strategies and Dataset Construction

2.3.3. Data Storage and Organizational Structure

3. Methodology

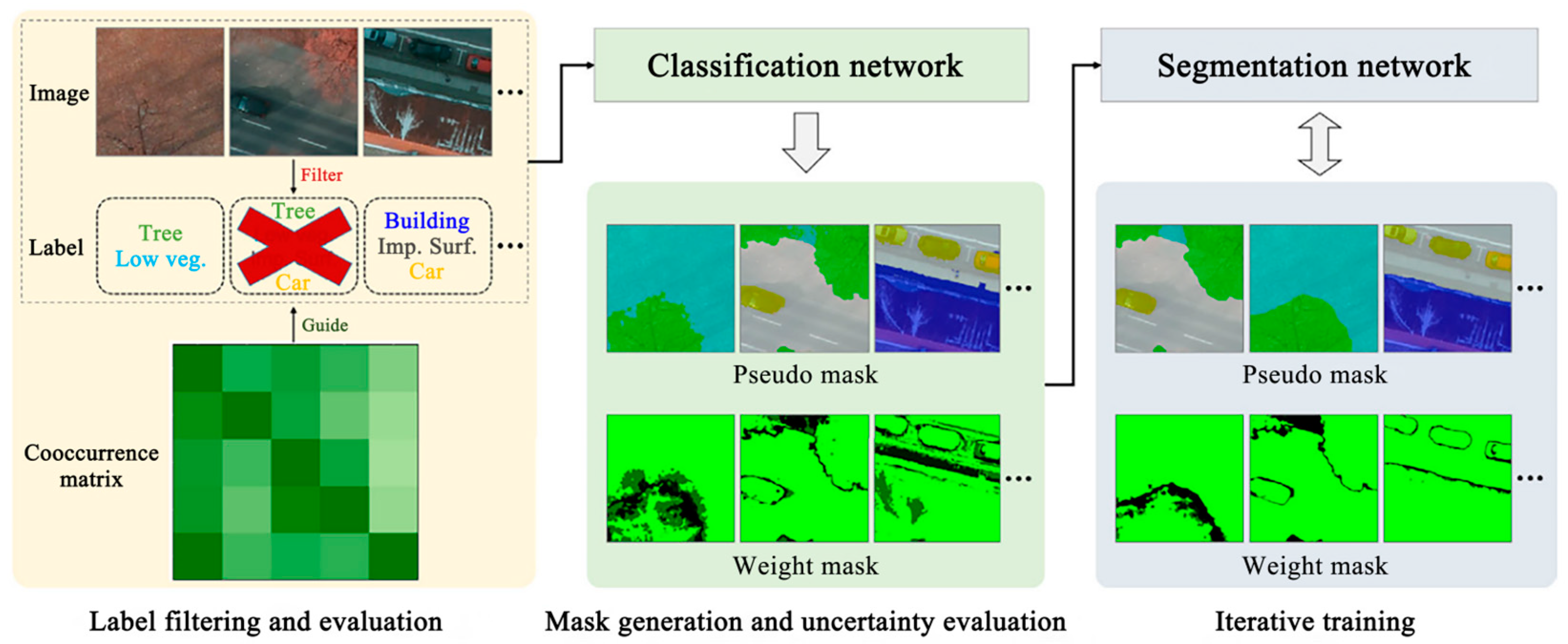

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Method

3.2. Semantic Segmentation Methods

3.2.1. Fully Supervised Methods

- FCN: As a pioneering work in the field of semantic segmentation, the Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) proposed by Long et al. (2015) [12] pioneered end-to-end pixel-level prediction for the first time. Its core is to replace the fully connected layer of the classification network with a convolutional layer to support arbitrary-sized inputs. FCN adopts an encoder–decoder structure, where the encoder performs feature extraction, and the decoder upsamples feature maps using transposed convolution. A key innovation is the introduction of skip connections, which fuse deep semantic information with shallow spatial details. This significantly improved boundary accuracy and laid the foundation for the field.

- U-Net: Ronneberger et al. (2015) [13] proposed U-Net, a symmetric U-shaped encoder–decoder architecture based on FCN. Its core innovation is the dense skip connections, which fuse the high-resolution features of the encoder layers directly with the corresponding layers of the decoder, effectively preserving the spatial details. This design enables U-Net to achieve accurate localization even with a small amount of labeled data, making it particularly suitable for tasks with limited labeled data such as medical image analysis [35].

- DeepLabV3+: Chen et al. (2018) [36] proposed DeepLabV3+, a further development of the DeepLab [37] family of models. As an extension of DeepLabV3, the model introduces an encoder–decoder structure and incorporates the Xception backbone network to enhance feature extraction. The encoder side employs the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) to capture contextual information at multiple scales through dilated convolution. The decoder side up-samples high-level semantic features and fuses them with the low-level features of the encoder to balance semantic richness and boundary details. The model significantly improves the segmentation performance of complex scenes by expanding the receptive field while maintaining the resolution through dilated convolution.

- SegFormer: SegFormer, proposed by Xie et al. (2021) [38], represents a new trend. It features a pure Transformer encoder that globally models contextual relationships via self-attention, and a lightweight MLP decoder that uniformly upsamples, concatenates, and fuses multi-scale features. The design completely abandons the inductive bias of convolution, enhancing its ability to capture long-range dependencies, and excels in both efficiency and accuracy, providing a new paradigm for semantic segmentation.

3.2.2. Weakly Supervised Method

3.3. Image Fusion Method

3.4. Experimental Design and Setup

3.4.1. Experimental Environment

3.4.2. Experimental Parameter Setting

3.4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Accuracy (Acc)

Mean Accuracy (mAcc)

Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU)

Recall

Precision

F1-Score

4. Results

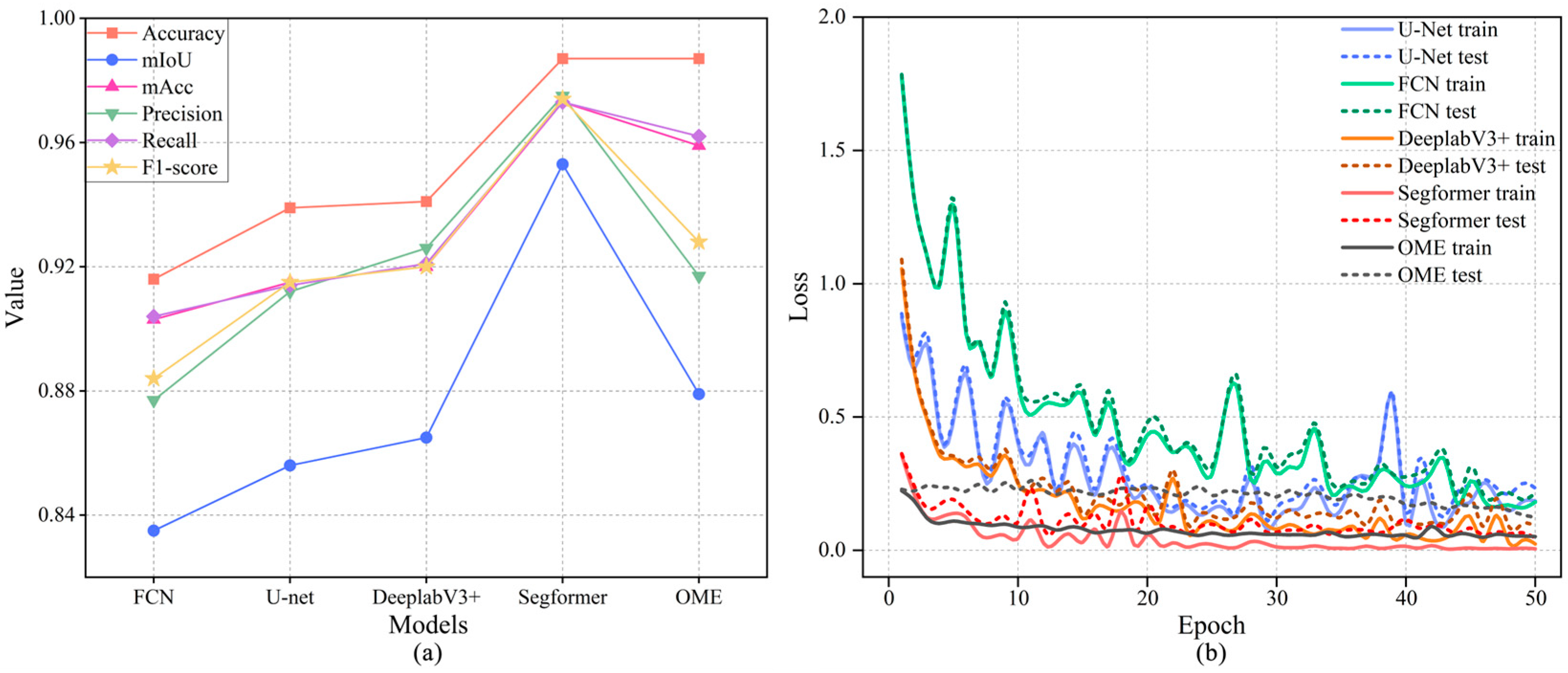

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Overall Accuracy

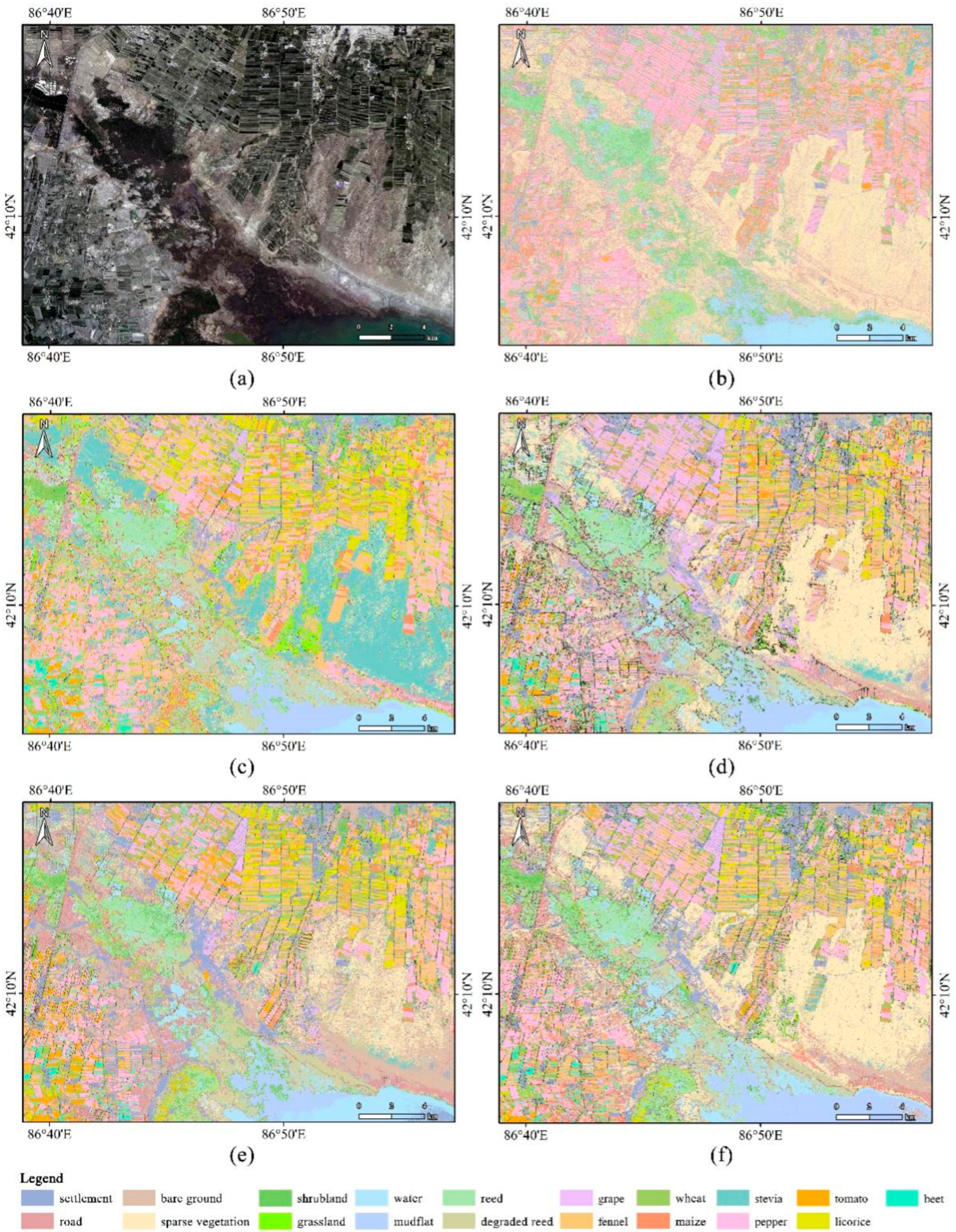

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Overall Classification Effectiveness

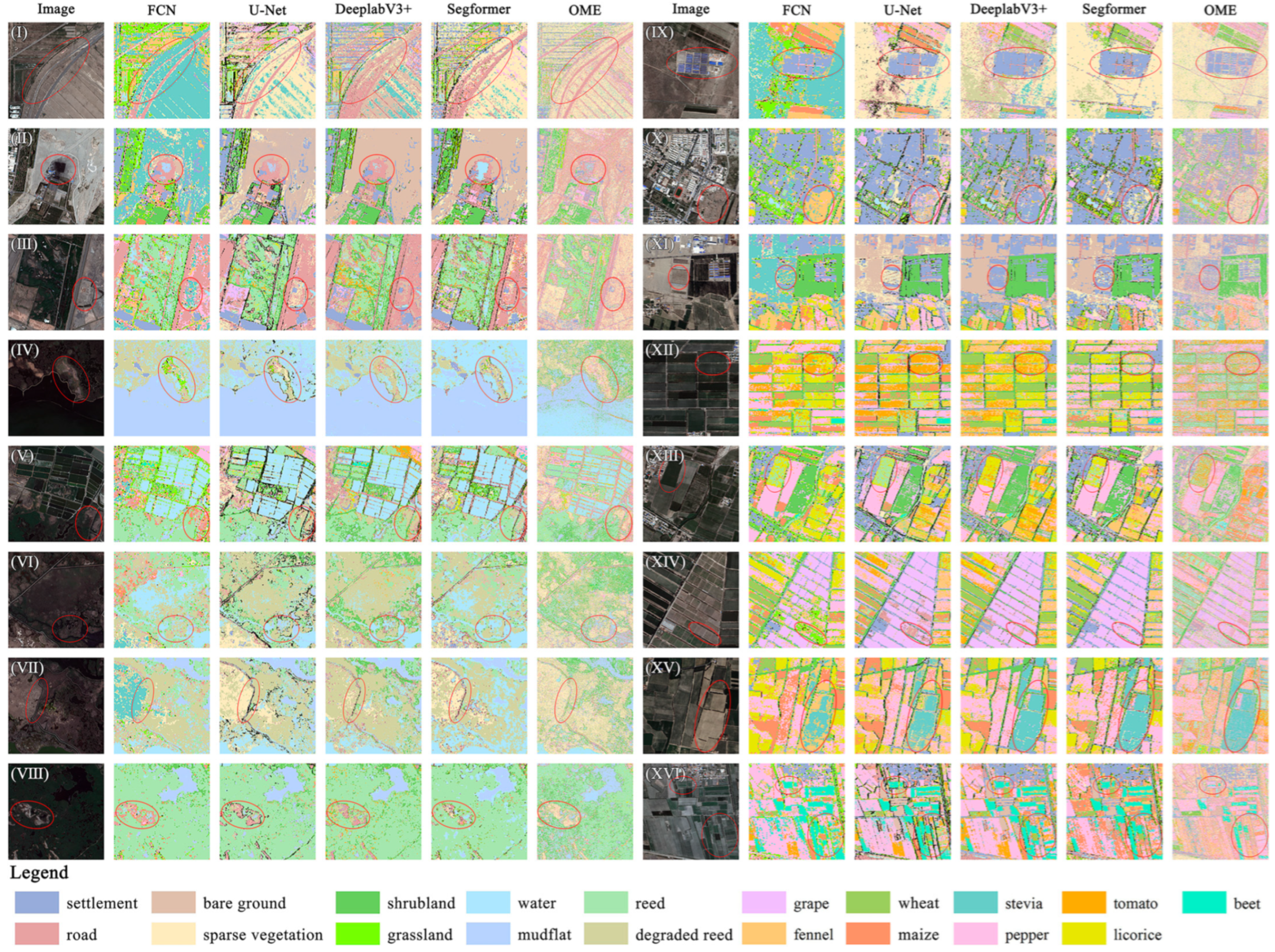

4.3. Detailed Performance Analysis of Typical Features

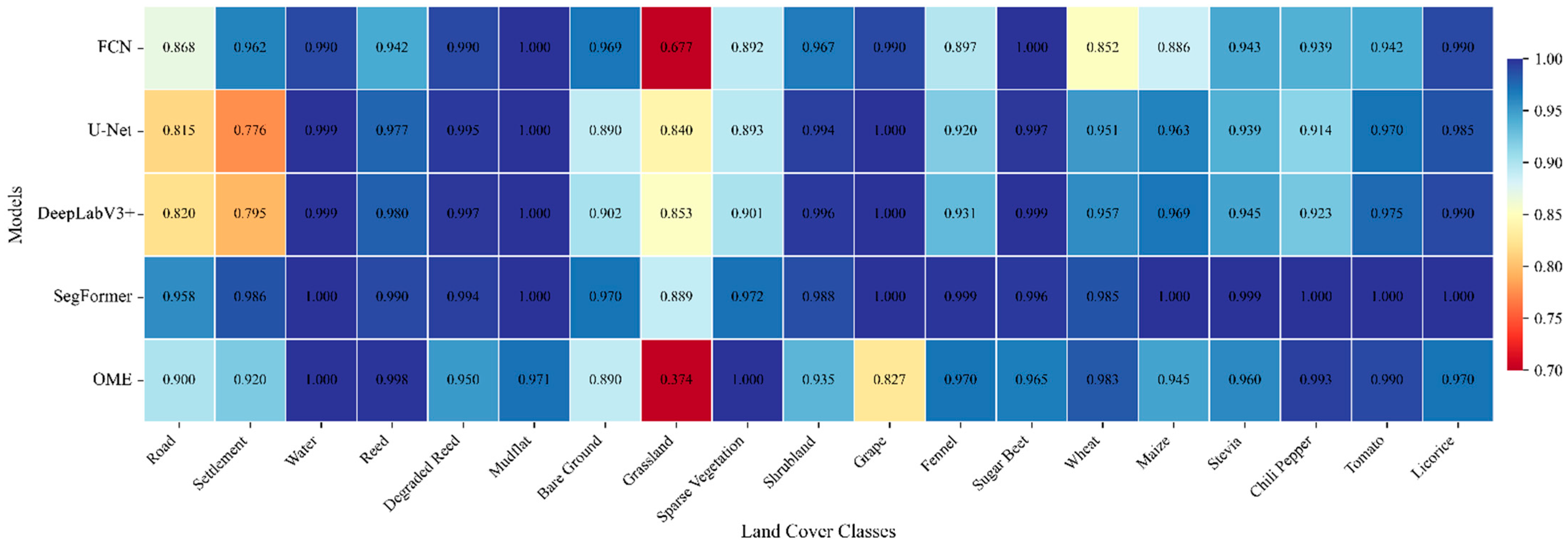

4.3.1. Comparative Analysis of Per-Class Performance

4.3.2. Analysis of Classification Details for Natural and Impervious Surfaces

4.3.3. Analysis of Classification Details for Wetland Vegetation and Hydrologic Systems

4.3.4. Analysis of Classification Details for Various Crops

4.4. Analysis of Ablation Experiments

5. Discussion

5.1. Evolution of the Model Architecture

5.2. Potential for Weakly Supervised Learning

5.3. Gain Effect of Fusion of Data from Multiple Models

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitsch, W.; Gosselink, J. Wetlands; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, N.C.; Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Finlayson, C.M. Global extent and distribution of wetlands: Trends and issues. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 69, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Gosselink, J.G. The value of wetlands: Importance of scale and landscape setting. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 35, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Power, M.E.; Comín, F.A.; Yockteng, R. Structural and functional loss in restored wetland ecosystems. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xie, G.; Deng, J.; Shao, K.; Hu, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, G. Effects of climate change and anthropogenic activities on lake environmental dynamics: A case study in Lake Bosten Catchment, NW China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ma, L.; Abuduwaili, J. Anthropogenic influences on environmental changes of lake Bosten, the largest inland freshwater lake in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.A.; Coops, N.C.; Roy, D.P.; White, J.C.; Hermosilla, T. Land cover 2.0. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 4254–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pei, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, R.; Sang, X.; Zhang, C. A review of remote sensing for environmental monitoring in China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Sha, Z.; Yu, M. Remote sensing imagery in vegetation mapping: A review. J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 1, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Tuia, D.; Mou, L.; Xia, G.-S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Fraundorfer, F. Deep learning in remote sensing: A comprehensive review and list of resources. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Yin, G.; Johnson, B.A. Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.H. A brief introduction to weakly supervised learning. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Murphy, K.P.; Yuille, A.L. Weakly-and semi-supervised learning of a deep convolutional network for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1742–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y.; Shen, X.; Cheng, M.-M.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, S. Stc: A simple to complex framework for weakly-supervised semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 2314–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2921–2929. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, E.; Yoon, S. Anti-adversarially manipulated attributions for weakly and semi-supervised semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 4071–4080. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Wang, Q.; Hung, W.-C.; Piramuthu, R.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Yang, M.-H. Weakly-supervised semantic segmentation via sub-category exploration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8991–9000. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Feng, J.; Liang, X.; Cheng, M.-M.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, S. Object region mining with adversarial erasing: A simple classification to semantic segmentation approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1568–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P. One model is enough: Toward multiclass weakly supervised remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4503513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gxokwe, S.; Dube, T.; Mazvimavi, D. Multispectral remote sensing of wetlands in semi-arid and arid areas: A review on applications, challenges and possible future research directions. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R. Multi-Source Data Fusion for Land Use Classification Using Deep Learning. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fauvel, M.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Chanussot, J.; Sveinsson, J.R. Spectral and spatial classification of hyperspectral data using SVMs and morphological profiles. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 3804–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Zhu, X.X. Data fusion and remote sensing: An ever-growing relationship. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2016, 4, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Plaza, A.; Camps-Valls, G.; Scheunders, P.; Nasrabadi, N.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral remote sensing data analysis and future challenges. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2013, 1, 6–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoya, N.; Grohnfeldt, C.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral and multispectral data fusion: A comparative review of the recent literature. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Wu, W.; Guo, S. IHS-GTF: A fusion method for optical and synthetic aperture radar data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; He, L.; Cheng, Q.; Long, X.; Yuan, Y. Hyperspectral and multispectral remote sensing image fusion based on endmember spatial information. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laben, C.A.; Brower, B.V. Process for Enhancing the Spatial Resolution of Multispectral Imagery Using Pan-Sharpening. U.S. Patent 6,011,875, 4 January 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Hao, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, B.; He, X.; et al. Climate change and water security in the northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Lin, L.; Zhengyong, Z.; Guining, Z.; Shan, N.; Ziwei, K.; Tongxia, W. Evaluation on the critical ecological space of the economic belt of Tianshan northslope. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yongjie, P. Analysis of new generation high-performance small satellite technology based on the Pleiades. Chin. Opt. 2013, 6, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Huang, H.; Houborg, R.; Martins, V.S. A global analysis of the temporal availability of PlanetScope high spatial resolution multi-spectral imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 264, 112586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongfei, G.; Yongzhong, Z.; Haowen, Y.; Shuwen, Y.; Qiang, B. Vegetation extraction from remote sensing images based on an improved U-Net model. J. Lanzhou Jiaotong Univ. 2025, 44, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Fan, X.; Fan, J.; Wang, N. Improved U-Net Remote Sensing Classification Algorithm Based on Multi-Feature Fusion Perception. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Zou, C.; Chen, J.; Han, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, N. Crop Type Identification Using High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images Based on an Improved DeepLabV3+ Network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Deria, A.; Hong, D.; Rasti, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. Multimodal fusion transformer for remote sensing image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5515620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, A.; Roy, S.K.; Ghamisi, P. WetMapFormer: A unified deep CNN and vision transformer for complex wetland mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2023, 120, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, B.; Lv, S.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y. Deep-learning-based semantic segmentation of remote sensing images: A survey. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 17, 8370–8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Man, Y.; Liu, B.; Yao, R. A survey of semi-and weakly supervised semantic segmentation of images. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 4259–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Yu, I.-J. Puzzle-cam: Improved localization via matching partial and full features. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Anchorage, AK, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 639–643. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P.; Zheng, Z. On the effectiveness of weakly supervised semantic segmentation for building extraction from high-resolution remote sensing imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 3266–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tang, P.; Corpetti, T.; Zhao, L. WTS: A Weakly towards strongly supervised learning framework for remote sensing land cover classification using segmentation models. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Zeng, D. Weakly supervised semantic segmentation with consistency-constrained multiclass attention for remote sensing scenes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5621118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Gao, J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, X. Contrastive tokens and label activation for remote sensing weakly supervised semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5620211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, G.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, A.; Jia, X. Point based weakly supervised deep learning for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5638416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Shen, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Li, Z. A weakly supervised semantic segmentation approach for damaged building extraction from postearthquake high-resolution remote-sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 6002705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, B.; Chanussot, J. Deep learning in multimodal remote sensing data fusion: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2022, 112, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Yokoya, N.; Iwasaki, A. Fusion of hyperspectral and LiDAR data with a novel ensemble classifier. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Dai, Z.; Hovy, E.; Luong, M.-T.; Le, Q.V. Unsupervised data augmentation for consistency training. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6256–6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Misra, I.; Schwing, A.G.; Kirillov, A.; Girdhar, R. Masked-attention mask transformer for universal image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1290–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanrajan, S.N.; Loganathan, A. Novel vision transformer–based bi-LSTM model for LU/LC prediction—Javadi Hills, India. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, F.R.; Carneiro, G. A survey on deep learning with noisy labels: How to train your model when you cannot trust on the annotations? In Proceedings of the 2020 33rd SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBGRAPI), Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 7–10 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, Q.; Caron, G.M.; Aloise, D. A practical survey on faster and lighter transformers. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Wang, Y.; Pan, J.; Liang, H.; Wang, S. Less Is More: A Lightweight Deep Learning Network for Remote Sensing Imagery Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4418913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Pleiades | PlanetScope-3 |

|---|---|---|

| Orbit Type | Sun-synchronous orbit | Sun-synchronous orbit |

| Orbit Altitude (km) | 694 | 475–600 |

| Inclination (°) | 97 | 97 |

| Revisit Period (days) | 1–3 | 1 |

| Sensor Type | TDI CCD & Multispectral | Push-broom |

| Number of Bands | 4 | 8 |

| Spatial Resolution | 0.5 m (Panchromatic) 2 m (Multispectral) | 3 m |

| Swath Width (km) | 20 × 20 | 32.5 × 19.5 |

| Image ID | 202406100519053_1206_02316 202406100519168_1004_04564 202406100518356_0707_03390 | 20240611_050805_88_24e6 20240611_050808_13_24e6 20240611_051017_27_24b7 20240611_051019_53_24b7 20240611_051021_78_2467 |

| Acquisition Date | 10 June 2024 | 11 June 2024 |

| Name | Specification |

|---|---|

| Workstation | Dell Precision 3660 (Dell Inc., Round Rock, TX, USA) |

| CPU | 13th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-13900K |

| GPU | NVIDIA RTX A6000 |

| Random Access Memory (RAM) | 128 GB |

| Hard Disk | 12 TB |

| Operating System | Ubuntu 22.04 |

| Programming Language | Python 3.8.5 |

| Deep Learning Framework & CUDA | PyTorch 1.10.1, CUDA 11.1 |

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Classes | 19 | Total number of semantic categories to segment |

| Image Size | 30 × 30 | Spatial dimensions of the input image in pixels |

| Batch Size | 16 | Number of samples processed per parameter update |

| Epochs | 50 | Number of complete passes through the training dataset |

| Maximum Iterations | 22,750 | Total number of training iterations (Epochs × (Training Samples/Batch Size)) |

| Optimizer | SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| Initial Learning Rate | 0.01 | Learning rate at the start of training |

| Loss Function | Cross-Entropy/Weighted Cross-Entropy | Standard Cross-Entropy (supervised methods)/ Weighted Cross-Entropy (OME) |

| Evaluation Interval | 5 Epochs | Performance evaluated on the validation set every 5 epochs |

| Model Selection Criterion | Best mIoU | Model with the highest mIoU on the validation set is selected |

| Actual\Predicted | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| True | TP (True Positive) | TN (True Negative) |

| False | FP (False Positive) | FN (False Negative) |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | mIoU (%) | mAcc (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCN | 91.65 | 83.57 | 90.35 | 87.75 | 90.45 | 88.48 |

| U-net | 93.92 | 85.65 | 91.54 | 91.24 | 91.42 | 91.59 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 94.14 | 86.58 | 92.05 | 92.61 | 92.12 | 92.08 |

| SegFormer | 98.75 | 95.33 | 97.36 | 97.50 | 97.31 | 97.47 |

| OME | 98.76 | 87.94 | 95.93 | 91.72 | 96.20 | 92.82 |

| Id | Name | FCN (%) | U-Net (%) | DeepLabV3+ (%) | SegFormer (%) | OME (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | road | 86.84 | 81.46 | 81.98 | 95.78 | 90.03 |

| 2 | settlement | 96.15 | 77.57 | 79.52 | 98.55 | 92.05 |

| 3 | water | 99.02 | 99.91 | 99.94 | 100.00 | 99.95 |

| 4 | reed | 94.24 | 97.74 | 97.95 | 99.04 | 99.82 |

| 5 | degraded reed | 99.03 | 99.54 | 99.72 | 99.36 | 95.01 |

| 6 | mudflat | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 97.13 |

| 7 | bare ground | 96.94 | 89.05 | 90.20 | 96.98 | 89.02 |

| 8 | grassland | 67.66 | 83.96 | 85.34 | 88.87 | 37.38 |

| 9 | Sparse vegetation | 89.18 | 89.35 | 90.14 | 97.18 | 99.97 |

| 10 | shrubland | 96.69 | 99.38 | 99.55 | 98.76 | 93.55 |

| 11 | grape | 99.02 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.0 | 82.66 |

| 12 | fennel | 89.74 | 92.02 | 93.11 | 99.87 | 97.02 |

| 13 | sugar beet | 100.00 | 99.72 | 99.94 | 99.58 | 96.51 |

| 14 | wheat | 85.17 | 95.10 | 95.73 | 98.54 | 98.33 |

| 15 | maize | 88.58 | 96.32 | 96.85 | 99.95 | 94.52 |

| 16 | stevia | 94.26 | 93.85 | 94.52 | 99.92 | 96.01 |

| 17 | chili pepper | 93.85 | 91.44 | 92.31 | 100.00 | 99.34 |

| 18 | tomato | 94.24 | 96.98 | 97.53 | 100.00 | 98.95 |

| 19 | licorice | 99.04 | 98.53 | 99.04 | 100.00 | 96.96 |

| Type | Model | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | mIoU (%) | mAcc (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full supervision | FCN | Pleiades | 93.31 | 83.22 | 89.72 | 87.64 | 89.86 | 88.44 |

| PlanetScope-3 | 69.44 | 37.04 | 49.95 | 48.45 | 49.94 | 48.05 | ||

| Pleiades& PlanetScope-3 | 91.65 | 83.52 | 90.34 | 87.77 | 90.45 | 88.48 | ||

| U-Net | Pleiades | 88.35 | 77.25 | 85.85 | 87.83 | 85.82 | 85.95 | |

| PlanetScope-3 | 56.14 | 22.28 | 31.96 | 43.24 | 31.95 | 31.02 | ||

| Pleiades& PlanetScope-3 | 93.95 | 85.67 | 91.55 | 91.25 | 91.44 | 91.50 | ||

| DeepLabV3+ | Pleiades | 92.02 | 83.65 | 90.54 | 91.44 | 90.56 | 90.40 | |

| PlanetScope-3 | 85.44 | 66.82 | 79.41 | 80.26 | 79.57 | 78.42 | ||

| Pleiades& PlanetScope-3 | 94.11 | 86.53 | 92.02 | 92.68 | 92.18 | 92.04 | ||

| SegFormer | Pleiades | 95.22 | 88.25 | 92.63 | 94.27 | 92.66 | 93.35 | |

| PlanetScope-3 | 84.63 | 68.04 | 83.88 | 77.68 | 83.85 | 80.21 | ||

| Pleiades& PlanetScope-3 | 98.75 | 95.33 | 97.37 | 97.59 | 97.34 | 97.42 | ||

| Weak supervision | OME | Pleiades | 94.54 | 84.85 | 91.28 | 90.15 | 89.55 | 90.81 |

| PlanetScope-3 | 86.35 | 64.12 | 81.95 | 76.82 | 82.22 | 77.93 | ||

| Pleiades& PlanetScope-3 | 98.76 | 87.94 | 95.96 | 91.71 | 96.20 | 92.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Samat, A.; Li, E.; Zhu, E.; Li, W. Fine-Grained Classification of Lakeshore Wetland–Cropland Mosaics via Multimodal RS Data Fusion and Weakly Supervised Learning: A Case Study of Bosten Lake, China. Land 2026, 15, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010092

Zhang J, Samat A, Li E, Zhu E, Li W. Fine-Grained Classification of Lakeshore Wetland–Cropland Mosaics via Multimodal RS Data Fusion and Weakly Supervised Learning: A Case Study of Bosten Lake, China. Land. 2026; 15(1):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010092

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jinyi, Alim Samat, Erzhu Li, Enzhao Zhu, and Wenbo Li. 2026. "Fine-Grained Classification of Lakeshore Wetland–Cropland Mosaics via Multimodal RS Data Fusion and Weakly Supervised Learning: A Case Study of Bosten Lake, China" Land 15, no. 1: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010092

APA StyleZhang, J., Samat, A., Li, E., Zhu, E., & Li, W. (2026). Fine-Grained Classification of Lakeshore Wetland–Cropland Mosaics via Multimodal RS Data Fusion and Weakly Supervised Learning: A Case Study of Bosten Lake, China. Land, 15(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010092