1. Introduction

Globally, issues of migration and settlement have been widely discussed over the past few decades. For instance, internal migration in Australia, the United States and Europe shows that migration and settlement are always embedded in specific spaces and places and different types of regions have distinct migration and settlement patterns [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In destination countries, homeownership is a key indicator of long-term commitment to place and an important driver of settlement intentions, which secures migrants’ legal status and strong local ties, and a lower probability of returning to the place of origin [

5,

6,

7]. In addition, migrant long-term settlement decisions depend on the balance between integration in the societal destination and continued ties to origin. Higher sociocultural integration in destinations is usually associated with lower intentions to return to origins [

8,

9]. Migrants often face physical and social segregation, which is regarded as an exclusion, reinforcing inequality and relative deprivation. In this sense, inclusive institutions and community networks are important for integration outcomes [

10,

11]. Together, these findings suggest that spatial context, housing tenure and social integration are central elements in understanding long-term settlement behavior.

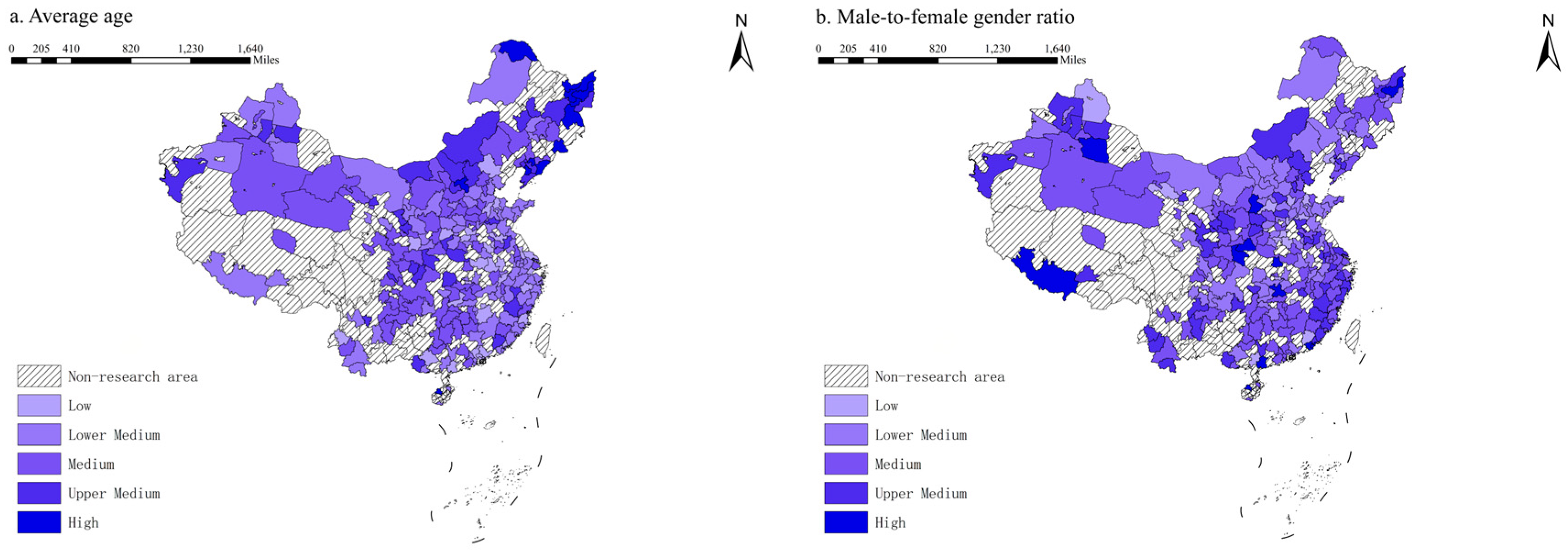

Distinguished from other countries, China established a rural–urban dual economy institution in the 1950s. During the past few decades, China has experienced rapid urbanization with a large and sustained influx of migrants into cities. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the urbanization rate of the resident population reached 66.14 percent in 2023. As shown in

Figure 1, the number of migrants reached 247 million in 2023, accounting for about 18 percent of the total population. Most migrants move for work or business opportunities and help to fill labor shortages in urban areas, which supports economic growth. According to the Rostow takeoff model, China is in the late takeoff and early maturity stage of economic development [

12]. However, the urbanization rate of the registered Hukou population is only 45.4 percent (Hukou is China’s unique household registration system. It records an individual’s place of birth and official place of origin, and determines access to a wide range of social benefits tied to locality, including education, healthcare, social security and public services (Song and Wu, 2022 [

13])). This is far behind the resident population. This gap indicates structural challenges in China’s urbanization process, as the disparity between the residents and registered urbanization rates suggests that full integration remains a long-term goal. Many rural migrants face a dilemma. They earn little income in their home villages but find it difficult to obtain equal rights and stable lives in cities. This has created a widespread condition of semi-urbanization, in which migrants live and work in cities for long periods without full legal or social recognition. With the implementation of a new, people-centered urbanization strategy and a series of Hukou reform policies, promoting the transition of migrant workers into long-term urban residents and ensuring equal access to basic public services have become key policy objectives. Achieving these goals requires not only supportive government policies but also migrants’ willingness to settle permanently in destination cities [

14]. Understanding the determinants of long-term settlement intention and finding ways to strengthen migrants’ integration into urban life are, therefore, crucial for urban governance and sustainable development.

Data Sources: China Migrant Population Service Center and The Seventh China Population Census Bulletin.

In China, housing plays a crucial role in shaping migrants’ long-term residence decisions. The rooted notion of “Live and work in peace and contentment” has been embedded in Chinese culture, influencing housing preferences and economic behaviors. Ensuring access to adequate housing is a fundamental prerequisite for migrants’ long-term settlement and social integration in cities [

15]. In recent years, migrants have tended to have more stable jobs and longer durations of residence in destination cities [

16], and large-scale population movement has been an inevitable outcome of structural change and industrial upgrading [

17]. Migrants increasingly hope to own housing in cities, but high housing prices create serious affordability problems, especially for rural migrants [

18]. As a result, migrants often have higher residential mobility than local residents and face more housing instability. Many live in peripheral locations, move frequently and have a weak sense of belonging in destination cities [

19]. Empirical studies for China confirm that urban homeownership promotes migrants’ urban integration and their willingness to stay, while the lack of secure housing is associated with a continued floating status [

18,

20,

21,

22].

In the process of rural–urban migration, many rural migrants keep their ownership of homestead land in their home villages while at the same time trying to invest in housing in cities for long-term relocation [

23]. Homestead land is a core part of rural collective construction land and gives rural households the right to build and occupy a dwelling. It also provides a basic safety net for rural livelihoods. An increasing number of studies show that homestead land and rural land rights more generally can have important effects on migration and settlement intentions [

15,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Some studies argue that the security function of homestead land discourages permanent urban settlement because a retained rural house provides a fallback option and reduces the need to build a permanent life in the city [

24,

25,

29,

30]. Other studies suggest that the ability to withdraw, transfer or mortgage rural land can support migration and settlement by relaxing liquidity constraints and providing resources for urban housing and consumption [

26,

27,

28]. Most of this literature, however, looks at rural land or urban housing separately and does not analyze how rural property in origin areas and urban property in destination cities work together to shape long-term settlement intentions.

Social integration is another critical factor influencing migrants’ decisions to settle permanently in cities [

27]. Unlike conventional migration studies, which often emphasize economic factors, social integration research highlights the role of urban inclusivity and migrant decision-making. Social integration encompasses not only personal satisfaction with urban life and future family prospects but also broader perceptions of environmental and policy support [

31]. From the perspective of social exclusion, migrants often face both physical and social segregation [

10]. Social exclusion reinforces existing inequalities, limiting migrants’ access to resources and creating a sense of relative deprivation [

11]. A well-developed urban environment, inclusive community networks and accessible public services are essential for fostering migrants’ economic integration and social adaptation [

32]. Enhancing social cohesion can help reduce urban–rural disparities, improve migrants’ sense of belonging and encourage long-term settlement [

20].

Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of homestead and urban homeownership on migrants’ long-term settlement intentions in Chinese cities. Using microdata from the 2017 China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS), it explores how local homeownership moderates this relationship.

This study makes three main contributions. First, it extends the classic push–pull framework by placing China’s dual property rights structure at the center of the analysis. It jointly models rural homestead land ownership (HLO) and local urban homeownership (LH) as origin-based and destination-based forces, rather than examining rural land or urban housing in isolation or treating them only as control variables. Second, it clarifies the conditions under which homestead land discourages urban settlement using nationally representative CMDS data and systematic heterogeneity analysis by age, income, migration distance, region and city type, and it shows that the fallback function of homesteads is stronger among older, low-income and inter provincial migrants in North, Central and Northeast China, which helps to reconcile the mixed findings in earlier studies. Third, it identifies the mechanisms through which dual property rights affect settlement intentions by showing that LH moderates the negative association between HLO and long-term settlement intention. Local homeownership also reinforces settlement intention through higher levels of social integration, and it further shows that these moderating and mediating effects vary across China’s different regional and urban contexts.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 sets out the theoretical framework and research hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the data, key variables and empirical strategy, and

Section 4 presents the main estimation results, including the baseline models and a series of robustness checks. This is followed by

Section 5 with the heterogeneity analysis and

Section 6 with the mechanism analysis.

Section 7 provides the discussion and indicates possible limitations, and

Section 8 concludes this paper.

6. Mechanism Analysis

The integration of long-term rural–urban migrants remains a persistent challenge in China’s urban transition [

50]. To further identify the mechanisms underlying migrants’ long-term residence intentions, it is essential to account for their level of social integration, which captures both their sense of belonging and the quality of their interpersonal connections within the destination city. The China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS) provides several items measuring emotional and social identification within the local area, including “I like the city/place where I live now” (X1), “I am concerned about the changes in the city/place where I live now” (X2), “I would like to be part of the local people” (X3), “I feel that the local people would like to accept me as part of them” (X4) and “I feel that I am already a local person” (X5). All items are recorded on a four-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree), where higher values denote stronger social integration.

To ensure comparability across items, all variables were standardized prior to analysis. As shown in

Table A1, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic is 0.830, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity is significant at the 1% level, confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Principal component analysis, following the criterion of retaining eigenvalues greater than one, yields a single common factor that explains 60.91% of the total variance (

Table A2). This factor is interpreted as the underlying construct of social integration and is constructed by aggregating the five items using their respective factor loadings. The rotated component matrix was derived using varimax rotation, and factor scores were computed with the regression method based on the rotated loadings shown in

Table A3 (According to

Table A3, the summation of each factor score status can be calculated as follows:

. Since only one factor is extracted, the total score is

).

On this basis, the relationship between homestead land ownership and migrants’ degree of social integration can be estimated using the following OLS models:

In Equation (5), represents the degree of social integration of migrants , which is the explained variable; is an explanatory variable that represents homestead land ownership; is a series of control variables, including personal, migration and family characteristics; is the regional fixed effect; and is the random interference term. In Equation (6), is a moderating variable, and the interaction term is also included.

Table 11 provides clear evidence that social integration serves as an important mechanism through which property-rights structures shape migrants’ long-term settlement intentions. Across all model specifications, homestead land ownership (HLO) is negatively and significantly associated with the level of social integration. This pattern is consistent even after the inclusion of extensive demographic, migration and household controls. The negative association indicates that migrants who retain rural homestead land tend to report weaker emotional attachment to the destination city, lower perceived acceptance by local residents, and a reduced sense of local identity. These findings reinforce the interpretation of homestead land as an origin-based anchor that constrains migrants’ urban incorporation. By contrast, local homeownership (LH) exhibits a positive and statistically significant relationship with social integration. Migrants who own housing in the destination city consistently display stronger identification with the host community, greater willingness to become part of local society, and a higher perceived acceptance by local residents. This confirms the role of urban property as an integrative asset: it stabilizes residence, strengthens local ties and facilitates migrants’ embedding into urban social networks.

Importantly, the interaction between HLO and LH is also positive and statistically significant. This suggests that owning a home in the destination city mitigates the negative effect of homestead land on social integration. In other words, among migrants who retain homestead land in their place of origin, those who acquire housing in the destination city show higher levels of social integration than those who do not. Urban homeownership, therefore, partially offsets the psychological and social pull associated with rural landholding, reducing migrants’ dependence on rural fallback security and facilitating their reorientation toward urban life.