1. Introduction

The Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 3, 10, and 11) underscore the critical importance of fostering urban environments that support health, well-being, and long-term sustainability. Evidence indicates that the urban built environment—including housing conditions, transportation networks, green spaces, and land-use patterns—exerts a profound influence on population health [

1,

2]. In recent years, emerging data sources such as high-resolution satellite imagery, pervasive street view data, dynamic GPS trajectories, and pervasive mobile sensing—coupled with transformative advances in Geographical Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI)—have advanced quantitative research in urban health, enabling more precise assessment of environmental exposures and health impacts [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Within the healthy city research domain, the role of urban green space in promoting health, well-being, and equity has been extensively examined. Empirical studies have demonstrated robust associations between urban greenery and life satisfaction using remote-sensing data and deep learning methods [

8,

9], while other research highlights the contributions of greenways and urban green infrastructure to stress recovery, relaxation, and improved mental health [

10,

11,

12]. Notably, studies on “green exercise” (i.e., physical activity in green spaces) report moderate but statistically significant positive effects on mental health, supporting the efficacy of short-duration, frequent, moderate-intensity interventions in urban contexts [

13,

14]. Systematic reviews further consolidate evidence for the health-promoting effects of urban green spaces. Comprehensive syntheses indicate that greenspace exposure is consistently associated with higher levels of physical activity and improved mental health outcomes, including reductions in anxiety and depression and enhanced perceived well-being [

15,

16,

17]. Achieving these benefits requires prioritizing green space maintenance, improving accessibility, and ensuring safe environments [

18]. Moreover, the quality of green space—including vegetation diversity, tree canopy coverage, and ecological connectivity—often exerts a stronger influence on health outcomes than green space quantity alone [

19,

20]. Taken together, these studies underscore that urban greening functions as a nature-based public health intervention capable of delivering substantial and measurable population-level health benefits.

Despite these empirical and methodological advances, the historical institutional and spatial origins of health-oriented urban green space planning remain under explored. During the nineteenth century, public health movements in Europe and North America, largely influenced by miasma theory, propagated concepts of urban hygiene, ventilation, and open space. These ideas led to a range of spatial interventions, including sewer construction, public parks, boulevards, and systematic street-tree planting [

21]. Importantly, such sanitary concepts shaped urban planning practices even before the consolidation of germ theory. Through colonial networks and transnational exchanges [

22,

23], they were subsequently disseminated to port and treaty-port cities, where practices such as botanical gardens, urban afforestation, and public parks became institutionalized [

24]. Historical and social science research has further emphasized that these transformations were not merely technical responses to environmental conditions, but were deeply shaped by governance regimes, cultural discourses, and institutional politics [

25,

26]. Health-oriented urban green space planning, therefore, embodied broader processes of institutional change and power negotiation, rather than simply reflecting landscape design or engineering solutions.

The “health-oriented urban green space” discussed in this study does not refer to contemporary public health planning based on epidemiological indicators or quantitative health models. Rather, in the late nineteenth-century Lingnan context, health-oriented urban green space denotes spatial interventions explicitly intended to improve urban sanitary conditions, regulate microclimates, mitigate environmental risks, and support everyday bodily comfort and social order. These spaces functioned through mechanisms such as the creation of ventilation corridors, tree shading and cooling, air purification, the provision of open and accessible space, and spatial separation or isolation. Such green space interventions were closely integrated with municipal engineering projects, street construction, and emerging urban governance institutions, forming a core component of early modern sanitary governance.

From a contemporary perspective, this historically situated understanding aligns closely with current interpretations of nature-based solutions and green infrastructure in healthy city research. Green spaces are no longer viewed merely as esthetic amenities, but as critical urban infrastructures that regulate environmental exposure, promote physical and mental well-being, and enhance urban resilience. Tracing this conceptual continuity provides an analytical bridge between historical practices and present-day healthy city agendas embedded in the SDG framework.

The persistent gap between contemporary quantitative approaches and the long-term institutional history of health-oriented urban green space planning limits the explanatory depth of current scholarship. Understanding how green space and sanitary concepts were historically introduced, negotiated, and localized is essential not only for identifying the mechanisms through which global ideas become embedded—or resisted—within local contexts, but also for illuminating the institutional continuities, spatial paradigms, and socio-ecological foundations of sustainable urban health governance.

Against this backdrop, the Lingnan area—represented by Guangzhou—offers a particularly revealing case. During the late Qing period, Guangzhou stood at the intersection of colonial expansion, regional competition, and rapid socio-spatial transformation under the treaty-port system. Early public green space experiments in the city and its adjacent treaty precincts reflected Western sanitary and landscape ideas, while simultaneously demonstrating local agency, reinterpretation, and adaptive transformation. By tracing the genesis and evolution of the American and British Gardens at the Thirteen Factories, the green space system of the Shameen concession, municipal greening practices in Hong Kong and Macao, and subsequent local initiatives such as Planting of street trees along Changdi Avenue in Guangzhou, this study reconstructs a historical trajectory from demonstration projects to local adaptation and, ultimately, to the institutional consolidation of health-oriented urban green space. In this way, the paper contributes a long-term, spatially grounded perspective that complements contemporary healthy city research, illustrating how global sanitary ideas intersected with local governance structures, ecological conditions, and social practices to produce enduring urban forms.

2. Materials and Methods

This study draws on a diverse set of historical materials from the late Qing and early Republican periods to document urban greening practices in the Lingnan region (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A). Primary sources include official gazettes and newspapers—such as

the Guangzhou Municipal Gazette and

the Official Gazette of Macao and the Province of Timor-Leste—as well as nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Western travelogs and reports. Additional materials consist of archival photographs and historical photo albums preserved in institutions including the Getty Research Institute, Harvard University’s Yenching Library, and the Yale Divinity School Library. These sources are complemented by municipal records related to urban improvement, sanitation, and street construction, together with relevant secondary scholarship by contemporary historians. These sources are complemented by municipal records related to urban improvement, sanitation, and street construction, together with relevant scholarship by contemporary historians. The use of multiple source types enables cross-validation between official documents, visual materials, and foreign observations. This approach reduces reliance on any single narrative perspective and strengthens the robustness of the historical interpretation.

All textual materials were analyzed in parallel with textual sources. with attention to recurring concepts related to health-oriented urban green space planning, including sanitation, ventilation, microclimate regulation, shading, afforestation, open-space provision, and environmental risk mitigation. The analysis also focused on how these concepts were explicitly linked to urban health, social order, and municipal responsibility.

Visual materials were analyzed in parallel with textual sources to reconstruct spatial configurations, design features, and functional roles of green spaces, including tree-lined streets, parks, waterfront landscapes, and ventilation corridors. Cross-source comparison was used to identify convergences and discrepancies among official documents, travel accounts, and visual evidence, thereby strengthening the historical interpretation.

The case studies include the American and British Gardens of the Thirteen Factories, the integrated green space system of the Shameen concession, municipal greening practice in Hong Kong and Macao, and the tree-lined Changdi Avenue in Guangzhou. These cases were selected for three main reasons. First, they represent different institutional contexts, including foreign concessions, colonial administrations, and local municipal governance. Second, they capture distinct stages in the development of urban greening, ranging from early demonstration projects to more institutionalized forms of municipal practice. Third, all cases are situated within the Lingnan region, ensuring ecological and cultural comparability.

Through chronological ordering and spatial comparison, the study reconstructs the spatio-historical trajectory of health-oriented urban greening in Lingnan area. This approach highlights the gradual transition from isolated landscape interventions to integrated components of urban infrastructure and sanitary governance. The historical findings are subsequently interpreted through contemporary frameworks of healthy cities, green infrastructure, and nature-based solutions. This analytical step allows the identification of early forms of health-oriented spatial governance, mechanisms of institutional transfer, and pathways of local adaptation that anticipate key principles of modern urban planning.

3. Results

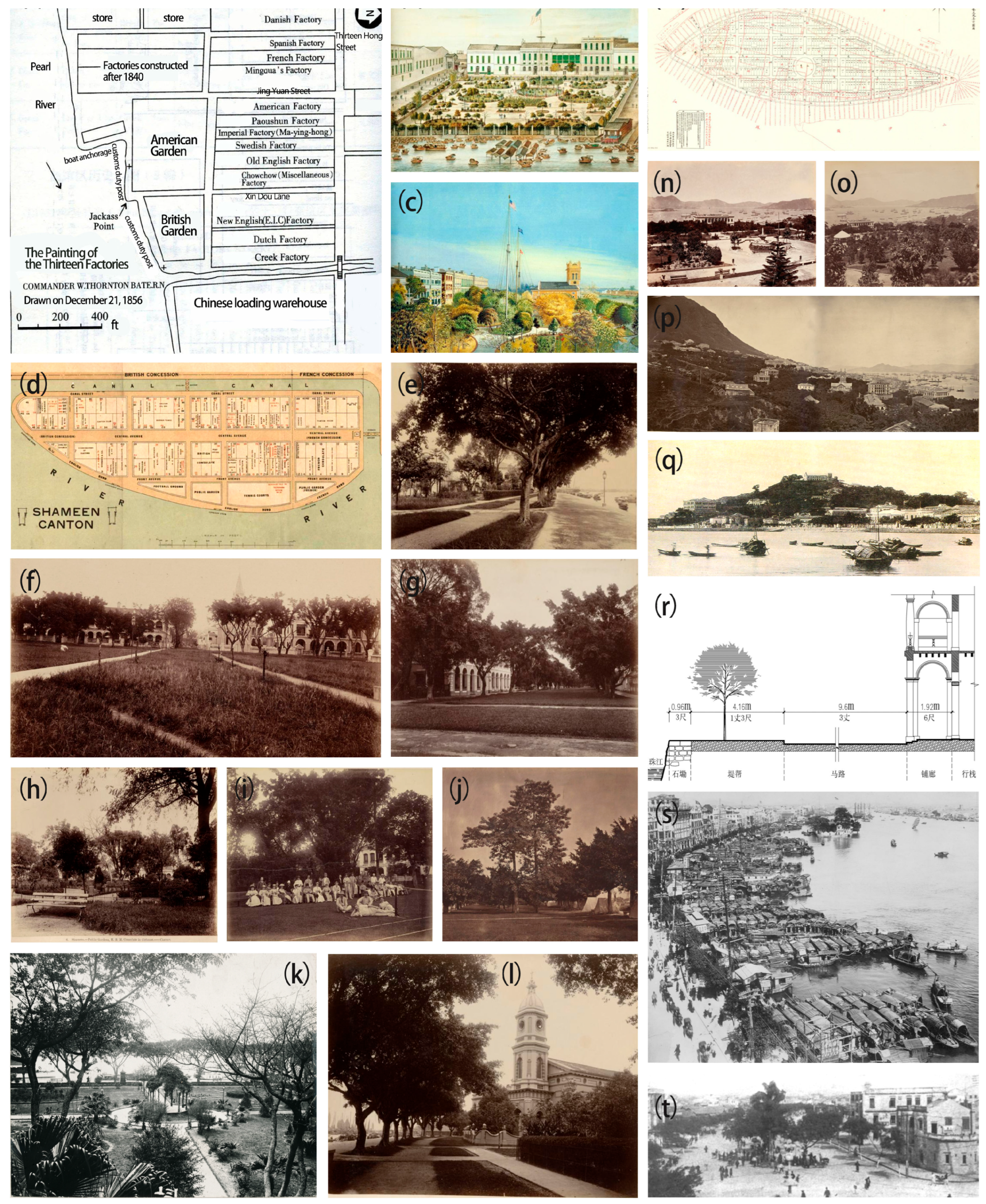

3.1. Emergence of Public Green Space in Guangzhou Under Western Influence—The American and British Gardens in Thirteen Factories

The selection of the Thirteen Factories’ forecourt as the site for the American and British Gardens was inevitable. Originally, this area was a tidal flat. After long-term siltation and intentional expansion by merchants, the Thirteen Factories Square gradually formed and was used as a temporary storage area for goods [

27]. With the increasing influx of Western traders, the district experienced growing spatial congestion, deteriorating sanitary conditions, and a chronic shortage of activity space. Following the First Opium War and the signing of the

Treaty of Nanjing—which opened five treaty ports and granted Westerners residential and movement privileges—the forecourt of the Thirteen Factories was compelled to undergo functional transformation. Seeking improved living and working conditions, Western merchants initiated the construction of two public gardens in front of the American and British factories (

Figure 1a–c) [

27].

The American and British Gardens represent one of the earliest attempts to introduce Western concepts of public green space into modern China, and they constitute the embryonic form of a “health-oriented urban green system” in Lingnan area. Their construction not only reshaped the local landscape but also offered a systematic response to Guangzhou’s climatic stresses, sanitary challenges, and social needs during the mid-nineteenth century.

First, the gardens significantly improved local microclimatic conditions. Their spatial layout incorporated flower beds of varied geometries—round, fan-shaped, and rectangular (

Figure 1b)—which created a strong sense of formal order while facilitating relatively smooth airflow within the site. The planting strategy combined low shrubs, open lawns, and tall shade trees (

Figure 1c), producing a multilayered vegetative structure that balanced shading and ventilation. Many trees were pruned into rounded or umbrella-shaped crowns (

Figure 1c), raising the canopy height and allowing air to circulate beneath. This design reduced direct solar exposure without obstructing airflow, effectively mitigating heat and humidity in Guangzhou’s subtropical climate.

Second, the gardens played a critical role in reducing disease risk in the Thirteen Factories area. As a major hub for cargo storage and commercial exchange, the former site of the Thirteen Factories accumulated large quantities of waste and dust. The widespread absence of effective sewage and sanitation infrastructure further exacerbated environmental conditions, leading to stagnant air and the concentration of foul and polluted gases. These conditions were widely perceived as major health risks.

Within this context, the introduction of vegetation functioned as an important spatial buffer against disease risk. Extensive plantings helped trap airborne particulates, increased local humidity through evapotranspiration, and diluted odorous and stagnant air near ground level, thereby mitigating perceived sources of illness. The construction of open green space also reorganized the spatial structure of the densely packed commercial quarter. Originally narrow and enclosed, the alleyways gained open spaces for evacuation and rest through the addition of greenery, alleviating overcrowding and crowd density issues. Under the dominant miasma theory of the nineteenth century—which attributed disease transmission to polluted and stagnant air [

28]—these spatial interventions were understood as effective means of lowering health risks. By increasing openness and enhancing ventilation, the gardens contributed to a spatial strategy aimed not at curing disease, but at preventing its emergence through environmental regulation, a core principle of early health-oriented urban green space planning.

Third, the American and British Gardens constituted an early exploration of health-oriented spatial sharing in Lingnan. At a time when the concept of public green space had not yet been clearly articulated in China, the gardens departed from the traditional Chinese garden model characterized by privacy, enclosure, and ornamental emphasis. Instead, they exhibited an early transition toward public accessibility. This shift was manifested in two key aspects. Functionally, the Gardens extended beyond esthetic appreciation and leisure to accommodate social and collective activities. A representative example is the construction of the British Church (

Figure 1c) in the British Garden in 1847, which provided a venue for religious services, social interaction, and community gatherings among Western merchants in Guangzhou [

29]. This intervention transformed the garden into a multifunctional public space with religious, social, and communal roles. Spatially, although the gardens were enclosed by transparent boundary walls, their internal spaces remained visually and physically connected to the surrounding urban fabric (as shown in

Figure 1b, the enclosing boundary of the garden can be observed). This openness contrasted sharply with the inward-facing layouts of traditional Chinese gardens (high walls, inward-facing courtyards, and so on) and reflected emerging modern values of accessibility, openness, and shared civic experience [

30].

Taken together, the American and British Gardens embodied key nineteenth-century Western ideas of environmental sanitation, spatial order, esthetics, and urban health. From the perspectives of spatial configuration, functional design, and planning ideology, they exemplify a tripartite health-oriented approach—microclimate regulation, sanitary improvement, and the creation of shared public space. As such, they mark the initial formation of health-oriented urban green space concepts in Lingnan and laid the ideological and practical foundations for later developments, including green space planning in the Shameen Concession and the street-tree planting project along Changdi Avenue.

3.2. Lingnan’s Early Healthy City Prototype: Public Green Space Planning and Construction in the Shameen Concession

3.2.1. Site-Selection Logic: Health-Oriented Considerations and Spatial Control

The establishment of the Shameen concession was guided by the 19th-century Western understanding of “health, safety, and environmental quality”. After the Thirteen Factories were destroyed by fire in 1856 and Anglo-French forces occupied Guangzhou [

31], foreign powers sought a replacement site for commercial and residential purposes. Several options were considered, including rebuilding the Thirteen Factories, relocating to Honam Island, or moving to Fa-ti. After a comprehensive assessment, Shameen emerged as the preferred location [

32].

Shameen’s selection was largely due to its unique natural environment. Originally a shallow waterway in the Pearl River, it was surrounded by water and featured a favorable wind channel, providing excellent air circulation and thermal regulation (

Figure 1d). Such natural ventilation was particularly important in Lingnan area with high temperature, high humidity and frequent epidemics. Another key factor was the island’s controllable boundaries. Through land reclamation, Shameen could be developed into a fully functional island. Its layout enables precise control over spatial access points, facilitating sanitary inspections, personnel management, and quarantine measures via cofferdams, bridges, and checkpoints. In the context of frequent epidemics in the 19th century, this “spatial isolation” effectively reduced the risk of disease transmission and aligned with contemporary urban health governance practices. Shameen also offered a strategic location: “near the city but not entering the city”. Situated across the river from Guangzhou’s old city, it maintained essential connections to markets, labor, and Chinese intermediaries, while avoiding the dense, unsanitary, and fire-prone conditions of the traditional urban core. This combination of proximity to urban resources and reduced health risks reflected an early form of health-oriented urban expansion.

Overall, the selection of Shameen was not solely a response to military or commercial imperatives. Rather, it reflected a multidimensional health rationale incorporating airflow optimization, microclimate moderation, epidemic prevention, and sanitary improvement. The formal construction of Shameen Concession further implemented this health-oriented spatial logic in planning regulations, transforming its space from traditional urban practices to modern public health and environmental improvement objectives.

3.2.2. Landscape Configuration and Planning Paradigms of Public Green Spaces

The planning of public green spaces in the Shameen concession extended the earlier practices from the American and British Gardens of the Thirteen Factories, particularly the use of plant-based landscape design to improve environmental quality [

30]. It further expanded the scale, spatial structure, and health-oriented functions of urban greenery.

At the level of overall spatial organization, Western engineers introduced a prototypical colonial urban layout. A clearly articulated road framework was established (

Figure 1d), including a wide, straight central tree-lined boulevard, a riverside ring road (

Figure 1e), and several north–south arterial streets. Together, these routes formed a legible orthogonal street network. The island was subsequently divided into twelve rectangular blocks (with slight variations at the edges), each further subdivided into narrow, elongated parcels [

29] (

Figure 1d). Such deep-lot, narrow-frontage parcels optimized land-use efficiency while shaping the streetscape, urban form, and spatial rhythm of Shameen’s built environment.

In terms of public green space planning, Shameen did not simply replicate the garden models of the Thirteen Factories. Instead, it developed an integrated system of green and open spaces driven by explicit goals related to health, landscape quality, and social well-being. The main east–west axis was defined by a broad, shaded promenade (

Figure 1f,g), serving as a primary pedestrian spine. The southern riverfront was designed as an open public activity zone, incorporating walkways (

Figure 1e), the British and French concession public gardens (

Figure 1h), sports fields such as football and tennis courts (

Figure 1i), and a children’s playground. Together, these elements formed a modern urban health system integrating “roadways, green spaces, and activity nodes”.

Among these spaces, the British Public Garden (

Figure 1h,k) most clearly embodied the landscape principles associated with health-oriented urban green space planning. The garden featured a large open lawn with high visual permeability and excellent air circulation. Pathways were arranged radially and circumferentially, reinforcing pedestrian accessibility and natural ventilation. Pavilions, benches, and other amenities supported recreation, psychological restoration, and social interaction. The plant palette continued the layered composition pioneered in the Thirteen Factories gardens: trees, shrubs, and lawns formed a stable vertical structure that provided shade, microclimate regulation, and esthetic coherence—an early archetype of green, health-supportive urban environments.

In terms of greening management, the maintenance and fund operation of these public green spaces are supervised by a special agency. Initially, the former “Garden Fund” of the Thirteen Factories oversaw maintenance. After compensation from the Qing government for the American and British Gardens, the fund continued managing Shameen’s landscapes and eventually became the “Canton Garden Fund”. Under its administration, notable greening progress was achieved. By February 1865, 645 trees had been planted (

Figure 1j,

Table 1). As shown in the table, these tree species are mainly local Lingnan tree species, such as Rose Apple Tree, Large-leaved Banyan, Wampi Tree, Sterculia nobilis, Mango Tree and Willow Tree, etc. [

33]. These heat-tolerant, humidity-adapted, and wind-resistant species provided a robust ecological basis for a comfortable microclimate. Public green spaces centered on native plants not only reduce maintenance costs but also align with the modern healthy city’s emphasis on ‘local ecological resilience’.

By the late nineteenth century, Shameen’s urban green spaces had approached Western standards in terms of environmental quality, spatial order, and esthetic refinement. The U.S. Consul General in Hong Kong, Rounse Velle Wildman, described Shameen as “ an artificial oval island, a half a mile long and some three hundred yards in breadth… as safe as though he were in Hong Kong or New York. The little settlement is as beautiful as a suburb on the Hudson, broad walks shaded with Banyan-trees, pretty gardens, broad tennis-courts, abicycletrack, and handsome brick houses, make one forget China” [

34]. Similarly, British writer Thomas Hodgson Liddell observed that, “If not for the river traffic, one might imagine oneself in Europe” (

Figure 1k) [

35].

It should be noted that, the apparent openness of Shameen’s green spaces was socially and politically constrained. Although formally designated as public, access to these spaces was largely restricted to concession residents, colonial officials, and selected elites. Chinese residents often faced conditional or limited entry, indicating that urban green spaces in the concession were embedded within colonial systems of spatial control and social hierarchy. This selective accessibility reveals that the health benefits generated by green space planning—such as improved microclimate, opportunities for recreation, and psychological restoration—were unevenly distributed. While expatriate communities and privileged groups disproportionately benefited from these environments, the broader local population remained largely excluded from their sanitary and health-enhancing effects. In this sense, green space functioned not only as a health infrastructure but also as a spatial instrument through which colonial power relations and social inequalities were reproduced.

Still, it is undeniable that the planning principles developed in Shameen exerted an indirect influence beyond the concession itself. Through processes of selective adoption and localized adaptation, these concepts informed later projects along the Changdi Bund and in Dashatou (

Figure 1m) [

36]. In this way, the concession’s planning and construction contributed to the gradual translation of Western healthy city ideas into the Lingnan context, laying institutional and technical foundations for subsequent urban redevelopment, roadside greening, and public health infrastructure.

3.3. Regional Demonstration: The Construction and Influence of Public Green Spaces in Hong Kong and Macao

After the Opium War, Hong Kong and Macao, as early treaty ports, pioneered the development of public green spaces as part of broader efforts to improve urban sanitation and mitigate epidemic risks. These initiatives were grounded in nineteenth-century Western sanitary thought, which linked disease transmission to stagnant air, excessive humidity, overcrowding, and poor environmental conditions.

Colonial authorities in both cities repeatedly emphasized the health-related functions of urban greenery. Government documents in Hong Kong noted that trees could decompose carbonic acids in the air, alleviate discomfort caused by tropical heat and humidity, and help reduce diseases associated with unsanitary environments [

37]. Similarly, the Macao Municipal Council discussed afforestation as a means of air purification, moisture absorption, climate regulation, and thermal comfort for street users [

38]. From the 1860s to the 1880s, street-tree planting expanded rapidly. By 1883, nearly all suitable streets in Hong Kong—from Pedder Street and the City Hall area to Robinson Road, Bonham Road, and Kennedy Road—were lined with trees. In the 1890s, Macao also completed a series of tree-lined boulevards with recreational and sanitary functions, exemplified by Avenida de Vasco da Gama.

These practices demonstrate that urban green spaces in Hong Kong and Macao were conceived as essential components of municipal sanitary infrastructure, closely aligned with contemporary concerns over epidemic prevention and public health governance.

Beyond disease control, public green spaces in Hong Kong and Macao also functioned as instruments of cultural regulation and civic education. Gardens and parks were designed not only to improve physical health, but also to shape public behavior, social norms, and everyday practices in accordance with colonial ideals of order, hygiene, and civility. The Hong Kong Botanical Garden (

Figure 1n,o), initially established for commercial and scientific purposes, was soon reframed as a space for improving residents’ physical and mental well-being. Regulations governing opening hours and permitted activities were introduced to maintain cleanliness, order, and proper conduct within the garden [

39]. In Macao, public spaces such as Vasco da Gama Garden, Jardim da Flora, the Leisure Area in front of the Municipal Council, the Hác-Sá Furnace Garden, and Luís de Camões Garden served differentiated but complementary functions, including commemoration, botanical cultivation, artistic display, sports, and physical exercise [

40]. This functional hybridity indicates an early shift in the role of urban green spaces—from sites of leisure toward tools of social governance. Through spatial design and behavioral regulation, green spaces became venues for producing disciplined urban subjects and promoting culturally defined notions of healthy and orderly urban life.

The health-oriented green space governance models developed in Hong Kong and Macao exerted a significant regional demonstration effect on Guangzhou and the wider Pearl River Delta. Although Guangzhou remained under a traditional urban management system for much of the nineteenth century, the visible success of greening practices in neighboring colonial cities gradually reshaped local perceptions among officials, merchants, and gentry.

First, conceptual enlightenment: public green spaces came to be understood as integral to modern urban governance rather than as luxury amenities. Through newspapers, commercial exchanges, official contacts, and labor mobility, the idea of green space as sanitary infrastructure spread from Hong Kong and Macao to Guangzhou [

41,

42].

Secondly, the imitation of the system and practice: Hong Kong initiated systematic afforestation in the 1840s and had established a mature network of tree-lined avenues by the 1880s. Guangzhou’s street-greening efforts, which began in the late nineteenth century, coincided with this mature phase of greening in Hong Kong and Macao. Many of Hong Kong’s early street trees were sourced from nurseries in Guangzhou, and much of the planting work was undertaken by Cantonese craftsmen [

42]. This bidirectional flow of seedlings, horticultural knowledge, and labor facilitated practical interaction between the cities and laid a firm foundation for the institutionalization of urban greening in Guangzhou.

Thirdly, political legitimation: the success of Hong Kong and Macao provided Guangzhou with a powerful source of legitimacy for advancing its own green space initiatives. Under the treaty-port system, urban greening became a visible means for local officials to demonstrate effective governance, modern sanitary capacity, and alignment with global urban trends. International comparison, modern sanitation logic, and regional competition together encouraged Guangzhou to adopt and institutionalize public green space development (

Figure 1p,q).

Through this process of regional demonstration and selective adaptation, Hong Kong and Macao did not simply export planning models. Instead, they catalyzed shifts in Guangzhou’s understanding of public greenery, its institutional arrangements, and its technical practices, laying an important foundation for the emergence of health-oriented urbanism in modern Lingnan.

3.4. Local Response: Planting of Street Trees in Changdi Avenue

Zhang Zhidong’s construction of the Pearl River embankment and the planting of street trees along Changdi Avenue marked the beginning of modern public green space development in local Guangzhou. This initiative constituted a direct local response to earlier precedents, including the American and British Gardens at the Thirteen Factories, the public green spaces of the Shameen Concession, and the urban greening practices of Hong Kong and Macao. Confronted with narrow streets, a severe shortage of green space, and deteriorating sanitary conditions in the old city, the Changdi greening project not only reshaped the urban spatial form but also introduced the modern notion of greenery as both municipal and health infrastructure. In this sense, it represented a critical shift from passive external influence to the active institutionalization of public greenery in Guangzhou.

In Zhang Zhidong’s embankment reconstruction plan, avenue trees were conceived as inseparable components of the overall engineering scheme. In his memorials to the throne, he explicitly stated: “Along the embankment, plant many trees to provide shade for pedestrians; inside the roadway, construct covered walkways to facilitate commercial activity…” [

43]. He further emphasized that “once the embankment is completed, the streets will be broad and clean, the trees lush, and the overall configuration will be greatly improved” (

Figure 1r) [

43]. These statements reveal that Zhang integrated trees, flood-protection structures, street cross-sections, arcades, and commercial layouts into a mutually reinforcing spatial system (

Figure 1s). Although he did not explicitly use the term hygiene, his emphasis on “broad and clean streets”, “shade for pedestrians”, and “lush trees” clearly reflects health-related concerns. Avenue planting was expected to reduce heat stress, improve pedestrian comfort, mitigate dust, enhance air quality, and ensure safer circulation—objectives closely aligned with healthy city principles.

From the perspective of health-oriented urban green space development, Zhang’s integrated treatment of avenue planting, street widening, arcade construction, and commercial organization indicates that greenery was understood as more than ornamental enhancement. It also functioned as an instrument of urban governance. Shaded walkways encouraged pedestrian movement and social interaction, improved streetscapes enhanced commercial attractiveness, and commercial vitality was regarded as a foundation of urban stability. This interlinked logic—hygiene, economic activity, and urban order—closely parallels the governance models observed in Hong Kong and Macao, where public greenery simultaneously served as health infrastructure and a key component of municipal management.

4. Discussion

The roadside tree-planting project along Changdi Boulevard marked the beginning of the institutionalization of streetscape greening in modern Guangzhou. After this initiative, street trees gradually became a standard feature of urban road construction, forming a distinctive characteristic of Guangzhou’s modern urban landscape.

During the Republican period, municipal authorities in Guangzhou continued to refine governance structures and technical standards for street greening. Regulations specified not only the locations of street trees along major roads, but also requirements for tree spacing, species selection, and long-term maintenance. Built forms that obstructed tree planting and air circulation—most notably arcade structures—were increasingly subject to restriction or removal. In 1928, the municipal government issued

the Revised Regulations for the Establishment of Model Residential Districts, integrating road classification with street-tree standards and establishing a comprehensive “road–tree–sidewalk” layout. For example, on first-class roads with a total width of 150 chi, sidewalks and central planting zones were clearly delineated, leaving 80 chi for the carriageway, 15 chi sidewalks on each side, 9 chi for tree belts, and 6 chi for road construction. Second- and third-class roads followed similar principles, with corresponding adjustments in tree-belt width and spatial allocation [

44].

These standards were further refined in the Outline of Urban Design for Guangzhou issued in 1932. The document said: “For ordinary planting areas along quiet cross streets in residential districts… tree-planting plots should be 1.5–2 m wide, and grass plots 1–1.6 m wide… while boulevards in garden residential areas should be 25–30 m wide” [

45]. The outline also introduced a citywide table of road widths by district (

Table 2), consolidating greening guidelines across commercial, residential, and administrative areas. As shown in the table, on major arterial roads in commercial, residential, and administrative districts—such as Tiban Boulevard—boulevards were typically planted with two or three rows of trees on either side. These tree belts were coordinated with tramlines and other infrastructure, indicating that greenery was increasingly treated as an integral element of urban spatial organization rather than as a decorative afterthought.

However, the expansion of commercial activity posed significant challenges to this greening agenda. In many central districts, streets were transformed into arcade-style markets, which encroached upon planting space and obstructed air circulation. In response, the Guangzhou Municipal Public Works Bureau issued repeated notices prohibiting tree planting along roads such as Baiyun Road, Jixiang Road, Gongyuan Road, Yonghan South Road, and Weixin Road (

Figure 1t). These notices explicitly emphasized that in densely populated and commercially active areas, extensive tree planting, the removal of obstructive arcades, and the maintenance of clean and well-ventilated streets were essential for ensuring urban hygiene and visual order [

46,

47,

48,

49]. In 1932, these measures were further reinforced through the promulgation of a Street Tree Protection Plan, which strengthened institutional safeguards for urban trees.

At this stage, the functions attributed to street trees had clearly expanded beyond simple beautification. Their health role—improving air circulation, reducing dust, moderating microclimate—was closely aligned with the nineteenth-century origins of modern urban planning, which emerged from efforts to address overcrowding, pollution, and epidemic risks. Yet these measures simultaneously pointed toward a broader understanding of urban health by enhancing comfort, walkability, and social vitality. In this sense, the institutionalization of street trees in Guangzhou represents not only the continuation of early health thinking but also an early transition toward health-oriented and well-being-oriented urban design. This governance orientation demonstrates that street trees had, by this time, been elevated to the status of essential municipal infrastructure with sanitary, environmental, and urban-order functions. Simultaneously, the practice of “prohibiting the construction of arcades while replacing them with street trees” also reflects that Guangzhou’s efforts to promote a healthy city were constrained by the demands of urban commercial development. This tension highlights the negotiation between public and private interests in the process of modern urbanization, while also revealing the difficult trade-offs municipal authorities faced in balancing limited resources with multiple objectives.

Returning to contemporary global discussions on “healthy, inclusive, and sustainable cities” as emphasized by the SDGs, the late-Qing public green space practices in Lingnan continue to offer valuable insights.

Firstly, the greening practice in Lingnan in late Qing Dynasty shows that effective health-oriented urban green space planning does not require high-cost or highly specialized engineering. Instead, it hinges on improving residents’ daily environmental conditions through basic spatial governance. Modest investments in nature-based solutions (NBS)—such as tree planting, open-space creation, and enhanced ventilation—can substantially improve public health. This approach aligns closely with SDG 11.7’s objective of “accessible, safe, and inclusive green spaces”, demonstrating the practicality and universal value of green infrastructure in developing countries’ cities.

Secondly, the Lingnan experience highlights a distinctive urban green space development model characterized by ‘cross-cultural integration—local adaptation—institutionalization’. Western garden concepts from the Thirteen Factories era, the systematic green space planning in the Shameen Concession, and the sanitation-focused municipal greening in Hong Kong and Macao collectively informed the foundational framework of modern greening in Lingnan. These foreign ideas were not merely copied; they were selectively reinterpreted to fit local social structures, financial constraints, and urban layouts. Zhang Zhidong’s tree-planting project along Changdi Avenue exemplifies this localized adaptation. This “selective absorption” mechanism offers crucial methodological insights for contemporary healthy city planning: rather than mechanically replicating international models, cities should dynamically balance global knowledge frameworks with local needs to achieve effective “localization of SDGs”.

Thirdly, early greening practices in Lingnan demonstrate the health synergies between natural and urban systems. Street trees contributed cooling, shading, dust reduction, and microclimate regulation, while public gardens provided spaces for social interaction, recreation, and psychological relief. Together, these interventions generated multidimensional health benefits. These historical experiences are particularly relevant for contemporary cities facing extreme weather, air pollution, rising chronic disease burdens, and mental-health challenges. They resonate with key themes in SDG 11 and the WHO Healthy Cities framework, particularly urban resilience, environmental justice, and health equity.

Finally, from a governance standpoint, the historical evidence emphasizes that building healthy cities requires stable and sustained public governance rather than one-off interventions. This principle aligns with contemporary institutional needs for Health Impact Assessment (HIA), urban green space performance monitoring, and GIS-based spatial health analysis.

From the perspective of the combination of historical urban planning research and the existing advanced technology, satellite imagery, street view images, GPS trajectories, mobile sensing, and GeoAI offer new opportunities to enrich historical urban planning studies. This enables us to conduct detailed, spatially explicit analyses of past urban environments. For instance, street view images, initially developed for contemporary urban analysis, have recently been applied to reconstruct and interpret historical streetscapes. This allows scholars to examine spatial continuity, visual permeability, and green space distribution across different periods [

50,

51]. Similarly, AI-based methods for detecting vegetation, street trees, and urban green infrastructure from satellite imagery have substantially improved the accuracy and scalability of green space mapping [

52,

53]. These techniques provide valuable methodological references for linking historical maps, archival photographs, and contemporary spatial data to assess long-term transformations in urban green systems. Mobile sensing and environmental exposure modeling further expand the potential to interpret historical urban health contexts by approximating thermal comfort, air quality, and walkability at the street level [

54,

55]. When combined with GeoAI approaches, such data-driven techniques can support the systematic analysis of institutional change, spatial governance, and the localization of planning paradigms across different historical periods [

56,

57].

Overall, the development of urban green spaces in late-Qing Lingnan was not merely a spatial modernization process, but rather the outcome of an interaction among public health imperatives, socio-cultural functions, and emerging modes of urban governance. The health-oriented urban green space planning of this period provides a valuable historical precedent for understanding how “modernity is localized” through concrete spatial interventions. At the same time, these experiences offer theoretical and practical guidance for advancing contemporary SDG-aligned urban agendas, particularly in promoting cities that are healthy, inclusive, and sustainable. Although this study relies primarily on qualitative historical materials, future research could integrate these emerging technologies to develop hybrid historical–computational frameworks, thereby enhancing the relevance of historical urban studies for contemporary planning and policy-making.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically examines cases of early urban green space development in Lingnan area: the American and British Gardens in the Thirteen Factories, the public green spaces in the Shameen concession, green space development in Hong Kong and Macao, and the roadside tree-planting project along Changdi Avenue. Together, these cases reveal how public green spaces in late-Qing Lingnan evolved from early experimentation to institutionalization and finally to localized adaptation. The findings show that these early green spaces were not mere copies of Western models. Instead, they represented health-oriented urban green space practices shaped by local socio-political conditions, environmental pressures, and urban governance needs.

- (1)

The American and British Gardens at the Thirteen Factories initiated Lingnan’s earliest “Healthy City Experiment”, addressing overcrowding, harsh microclimates, and epidemic risks, while reflecting Western culture and landscaping ideals.

- (2)

The public green spaces in the Shameen concession translated above early ideas into an institutionalized planning paradigm through systematic street networks and integrated greenery as well as greening management. They addressed local health needs, provided venues for social and recreational activities. Politically, the planning demonstrated Western administrative capacity and served as a prototype for a healthy city in Guangzhou.

- (3)

Green space developments in Hong Kong and Macao exerted a regional demonstration effect, improving sanitation, moderating microclimates, and mitigating epidemic risks, while also fostering civic culture and social governance. The transfer of these practices—through institutional exchange, technical expertise, and labor mobility—reinforced Guangzhou’s recognition of greenery as vital for public health and municipal management.

- (4)

Roadside tree planting along Changdi Avenue exemplified local adaptation, improving the environment, supporting social activity and commerce, and integrating greenery into urban governance.

Overall, the evolution of modern public green spaces in Lingnan followed a dynamic trajectory of “exogenous demonstration—local assimilation—institutional consolidation”. This historical pathway offers key insights for contemporary SDG 11 objectives, including improving everyday environmental conditions, leveraging nature-based solutions for public health, and embedding urban green space governance within stable institutional frameworks. Many principles emphasized in modern healthy city planning—such as microclimate regulation, accessible public spaces, and reduction in environmental burdens—already emerged in nineteenth-century Lingnan. These early practices mark the emergence of modern urban health thinking in southern China and highlight the foundational role of local adaptation in shaping health-oriented urban planning, anticipating contemporary global efforts to integrate health, well-being, resilience, and environmental justice into city design. Future research could further build on this historical perspective by integrating emerging technologies—such as street view imagery, satellite-based green space detection, mobile sensing, and GeoAI—to explore how health-oriented planning principles identified in historical contexts can be examined, validated, and extended through contemporary spatial data.